Abstract

Afibrinogenemia is a rare autosomal recessive bleeding disorder with an estimated prevalence of 1:1,000,000. Usual presentation of this disorder is spontaneous bleeding, bleeding after minor trauma and excessive bleeding during interventional procedures. Paradoxically, few patients with afibrinogenemia may also suffer from severe thromboembolic complications. The management of these patients is particularly challenging because they are not only at risk of thrombosis but also of bleeding. We are presenting a case of 33-year-old male patient of congenital afibrinogenemia who had two episodes myocardial infarction in a span of two years. The patient was managed conservatively with antiplatelet therapy and thrombolytic therapy was not given due to high risk for bleeding.

Keywords: Afibrinogenemia, antiplatelet therapy, myocardial infarction

INTRODUCTION

Afibrinogenaemia is a rare hereditary bleeding disorder with autosomal recessive inheritance. This disorder was first described in 1920 by Rabe et al.[1] It is characterized mainly by extremely low fibrinogen levels in plasma.[2] Though both minor and major spontaneous or post-operative bleeding is the most common presentation of this rare disorder, there are several case reports of thrombotic complications also.[3,4,5] There are few reports of myocardial infarction (MI) in the literature in patients of afibrinogenemia.[2] We are reporting the first case where a patient had recurrent myocardial infarction.

CASE REPORT

A 33-year-old man, who was a confirmed case of congenital afibrinogenemia and was diagnosed six years back when he had excessive bleeding following trauma over face and persisted even after suturing that area, presenting to us with severe retro sternal chest pain of 10 h duration. He had a past history of myocardial infarction (MI) two years back and was advised dual antiplatelet therapy. But as per hematologist advised he stopped taking dual antiplatelet treatment.

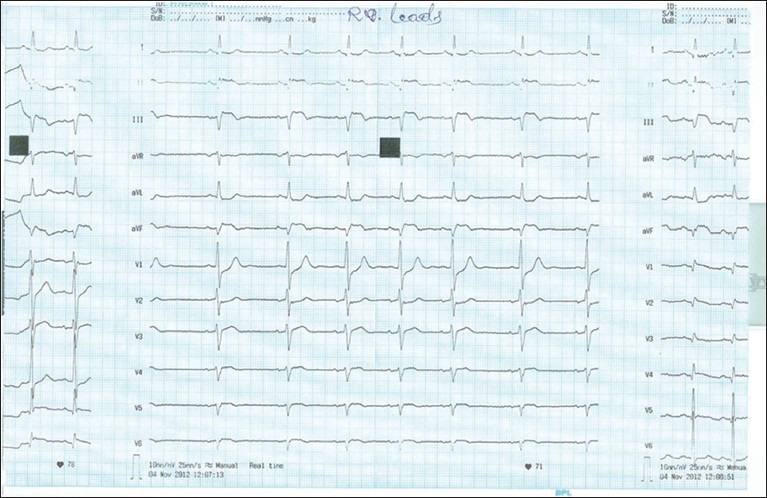

He was born of second degree consanguineous marriage with history of sibling death after birth. On admission, his pulse rate was 90/min and blood pressure was 130/90 mm of Hg. Cardiovascular and other system examinations were found to be normal. Electrocardiogram showed 2 mm ST segment elevation in leads II, III, aVF and ST depression in leads I and aVL [Figure 1]. Echocardiogram revealed inferior wall hypokinesia, and left ventricular ejection fraction was 60%. Troponin T obtained at admission was strongly positive with 1.24 ng/ml (normal- <0.1 ng/ml). Coagulation profile was sent after admission and tests revealed absent fibrinogen using the Clauss method, markedly reduced fibrinogen antigen level, normal platelet count and bleeding time, infinitely prolonged activated partial thromboplastin time (APTT), prothrombin time (PT) and thrombin time.

Figure 1.

Prominent ‘q’ wave, ST segment elevation and ‘T’ wave inversion in lead II, III and aVF with ST segment depression seen in lead I and aVL. Right sided chest leads (V4R-V6R) showed <1 mm ST segment elevation

As this patient had high risk for bleeding, thrombolysis or primary percutaneous transluminal coronary angioplasty (PTCA) was not advised though he had ongoing chest pain. He was treated with dual antiplatelet therapy (aspirin plus clopidogrel), statins, betablocker, angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitors and injection nitroglycerin (NTG). After few hours of treatment, the chest pain subsided and ST segment showed evolving changes. His admission lipid profile was normal (low density lipoprotein 112 mg/dL, triglyceride 128 mg/dL, high density lipoprotein 40 mg/dL). Liver function tests were normal, with negative fibrinogen degradation product. The patient did not experience a recurrence of angina and was discharged three days after admission with dual antiplatelet therapy.

DISCUSSION

Fibrinogen, the soluble precursor of fibrin, is produced in the hepatocyte. Fibrinogen is the major coagulation protein in blood by mass: Normal fibrinogen levels vary between 1.5 and 3.5 g/L.[5] Bleeding, which usually manifests already in the neonatal period (85% of cases presenting umbilical cord bleeding), is the main complication of afibrinogenemia.[4]

Paradoxically, both arterial and venous thromboembolic complications have also been reported in afibrinogenemic patients.[6] These complications can occur in the presence of concomitant risk factors such as a co-inherited thrombophilic risk factor or after replacement therapy.[7] However, in many patients, no known risk factors are present. Several hypotheses have been put forward to explain this predisposition to thrombosis. First, even in the absence of fibrinogen, platelet aggregation is possible due to the action of von Willebrand factor and, in contrast to patients with hemophilia, afibrinogenemic patients are able to generate thrombin, both in the initial phase of limited production and also in the secondary burst of thrombin generation.[6] Second, the increase of prothrombin activation fragments or thrombin-antithrombin complexes have been observed, reflecting enhanced thrombin generation. So, antithrombin role has also been attributed to fibrinogen because in its absence, clearance of thrombin is impaired.[6]

Though there are several reports of both arterial and venous thrombosis in afibrinogenemia,[7,8] only a few cases have been reported where these patients developed MI.[2] With recurrent MI, this is the first case we are reporting. Treatment of MI in the presence of a bleeding disorder like afibrinogenemia is difficult as administration of thrombolysis and anticoagulant will increase bleeding. PTCA is also not advisable as this patient had prolonged APTT and PT. So, we treated with both aspirin and clopidogrel in our case. As patient stopped taking dual antiplatelet therapy he had recurrence of MI. He had inferior wall MI in the both the episodes. Chest pain subsided after starting injection of NTG and the area of myocardial involvement was also small, we managed the patient conservatively, and discharged him on dual antiplatelet therapy.

Treatment of MI in case of hereditary bleeding disorder is not clear so far. Further study is needed on this aspect to determine the best treatment that we can provide to them. Until then dual antiplatelet therapyshould be recommended to all these patient with hereditary bleeding disorder with close supervision of bleeding diathesis since without this treatment they may have recurrences.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Rabe F, Salomon E. Ueber-faserstoffmangel im Blute bei einem Falle von Hämophilie. Arch Int Med. 1920;95:2–14. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kumar N, Padma Kumar R, Ramesh B, Garg N. Afibrinogenaemia: A rare cause of young myocardial infarct. Singapore Med J. 2008;49:e104. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lak M, Keihani M, Elahi F, Peyvandi F, Mannucci PM. Bleeding and thrombosis in 55 patients with inherited afibrinogenaemia. Br J Haematol. 1999;107:204–6. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2141.1999.01681.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Castaman G, Lunardi M, Rigo L, Mastroeni V, Bonoldi E, Rodeghiero F. Severe spontaneous arterial thrombotic manifestations in patients with inherited hypo- and afibrinogenemia. Haemophilia. 2009;15:533–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2516.2009.01939.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.de Moerloose P, Boehlen F, Neerman-Arbez M. Fibrinogen and the risk of thrombosis. Semin Thromb Hemost. 2010;36:7–17. doi: 10.1055/s-0030-1248720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Taslimi R, Golshani K. Thrombotic and hemorrhagic presentation of congenital hypo/afibrinogenemia. Am J Emerg Med. 2011;29:573–e3-5. doi: 10.1016/j.ajem.2010.05.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chevalier Y, Dargaud Y, Argaud L, Ninet J, Jouanneau E, Négrier C. Successive bleeding and thrombotic complications in a patient with afibrinogenemia: A case report. Thromb Res. 2011;128:296–8. doi: 10.1016/j.thromres.2011.03.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Roqué H, Stephenson C, Lee MJ, Funai EF, Popiolek D, Kim E, et al. Pregnancy-related thrombosis in a woman with congenital afibrinogenemia: A report of two successful pregnancies. Am J Hematol. 2004;76:267–70. doi: 10.1002/ajh.20110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]