Abstract

A 50-year-old man with no previous history of cardiovascular disease or risk factors was admitted for syncope and orthopnea. Importantly, he underwent recent chemotherapy with 5-fluorouracil (5-FU) until 1 day before his acute presentation. In the emergency room, patient developed asystole and was successfully resuscitated for 2 min. At coronary angiography, no signs of coronary artery disease were detectable, but transthoracic echocardiography showed a severely decreased left-ventricular systolic function. Due to the progressive cardiogenic shock, an extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO) support was used as bridge-to-recovery and to avoid the use of sympathomimetics with their known disadvantages. On ECMO support, hemodynamic stabilization was evident and medical heart failure treatment was commenced. Left-ventricular function recovered to normal values within a short period of time. Cardiac complications after chemotherapy with 5-FU are not rare and should be taken into consideration even in acute heart failure with cardiogenic shock. ECMO as the most potent form of acute cardiorespiratory support enables complete relief of cardiac workload and therefore recovery of cardiac function.

Keywords: Acute heart failure, cardiogenic shock, extracorporeal membrane oxygenation support, 5-fluorouracil

INTRODUCTION

5-fluorouracil (5-FU) is a widely used chemotherapeutic drug and cardiac complications are not rare.[1] Angina is the most common clinical presentation. However myocardial infarction, Tako-Tsubo-like syndrome and cardiogenic shock are also described.[1,2,3]

CASE REPORT

A 50-year-old man (weight 70 kg, height 180 cm) was admitted to a primary care hospital following an episode of syncope. He reported acute orthopnea and an attack of sweating at night accompanied by nausea and vomiting before loss of consciousness for 1 min. Angina pectoris was denied by patient.

In the emergency room, patient developed asystole and was immediately and successfully resuscitated for 2 min. Afterwards, he was fully oriented without any neurological dysfunction. Consequently, he was transferred to our heart center for further diagnostic work-up and therapy.

Importantly, patient had no previous history of cardiovascular disease or risk factors, but was diagnosed with colorectal cancer (cT3 N1 M0) and underwent recent neoadjuvant chemotherapy with 5-FU (9500 mg by continuous infusion over a period of 120 h) until 1 day before his acute presentation. His physical examination revealed hypotensive blood pressures (89/58 mmHg) and heart rate at rest of 95 bpm. There was distension of the jugular veins with normal heart sounds. The electrocardiogram documented sinus rhythm at 95 bpm with non-significant ST-elevation in leads II, III, aVF. High-sensitive troponin T (60 ng/L; upper reference value 14 ng/L) and creatine kinase-MB fraction (0.74 μmol/L*s; upper reference value 0.41 μmol/L*s) were slightly elevated. Creatinine kinase showed a normal value of 0.93 μmol/L*s (upper reference value 3.17 μmol/L*s).

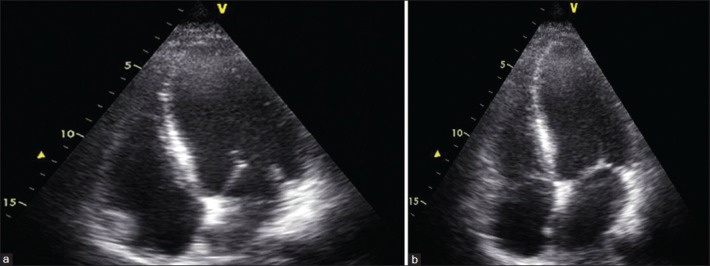

Initial transthoracic echocardiography (TTE) showed a normal sized left ventricle (left-ventricular end-diastolic diameter: 48 mm, left-ventricular end-diastolic volume: 103 mL) with global hypokinesia and severely decreased left-ventricular systolic function [left-ventricular ejection fraction: 16%; [Figure 1a and b]. Pericardial effusion and relevant valve disease were excluded. Coronary arteries were normal at angiography.

Figure 1.

Transthoracic echocardiography on day 1 (a) Apical four-chamber view during diastole, (b) Apical four-chamber view during systole (There is global hypokinesia with severely impaired thickening of the left ventricular wall in systole)

One day after admission, patient had persistent hypotension with increasing lactate levels as a sign of peripheral malperfusion. On repeat echocardiographic examination, left-ventricular systolic function was found to have further decreased with a left-ventricular ejection fraction of <10%. Due to the progressive cardiogenic shock, we decided to treat this condition by the use of an extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO) support by percutaneous implantation. On ECMO support, hemodynamic stabilization was evident and medical heart failure treatment including angiotensin-converting enzyme-inhibitor, diuretics and spironolactone was commenced. After 4 days with ECMO therapy, left-ventricular ejection fraction improved to 45% and lactate levels were in normal ranges (<2 mmol/L). Therefore, ECMO-flow was reduced slowly up to 1.5 L/min. Due to the stable lactate levels (<2 mmol/L) successful ECMO explantation was performed on day 5.

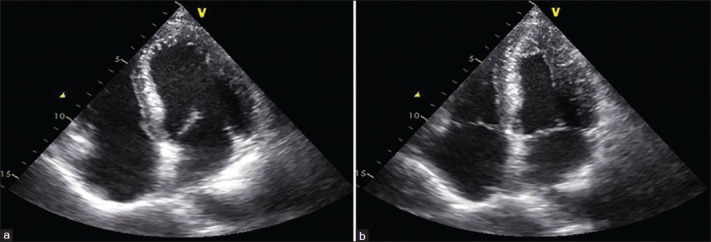

The following course was uncomplicated with normalization of blood pressures and no signs of heart failure. Eight days after admission, he was transferred to the normal ward. Left-ventricular ejection fraction was now recovered to a normal value of 60% [Figure 2a and b]. For confirmation and further differential diagnosis cardiac, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) was performed. The MRI showed a normal sized left ventricle (left ventricular end-diastolic volume: 149 mL; normal value 102-235 mL) with normal ejection fraction of 57% and without any specific wall motion abnormality. T2-weighted imaging revealed mild degree of generalized myocardial edema. Furthermore, T1-weighted imaging showed pronounced early contrast enhancement, indicating some degree of myocardial hyperemia. No signs of myocardial scar or necrosis were detectable. Patient was discharged from hospital in a stable cardiac condition without symptoms of heart failure 11 days after admission.

Figure 2.

Transthoracic echocardiography on day 10 (a) Apical four-chamber view during diastole, (b) Apical four-chamber view during systole. There is a normal thickening of the left ventricular wall in systole

DISCUSSION

This report describes a patient with no history of cardiovascular disease who experienced acute left-ventricular failure after administration of 5-FU. Cardiac complications ranging from angina pectoris to cardiogenic shock after chemotherapy with 5-FU are not rare.[1,2,3] Coronary vasospasm, endothelial damage with consequent thrombus formation, increased myocardial oxygen demand, block of myocardial cell metabolism and Tako-Tsubo-like syndrome with supraphysiologic levels of plasma catecholamines are discussed as potential pathogenetic mechanisms.[1,4] Our patient did not report any angina and obstructive coronary lesions were excluded by angiography. Echocardiography did not reveal an apical ballooning as common in Tako-Tsubo-like syndrome. The cardiac MRI of our patient strengthens the concept of an additional temporary myocardial inflammation. Increased global myocardial edema and evidence of myocardial hyperemia are compatible with a regressive inflammation.[5] Unfortunately, the MRI could not be performed in the acute setting with severely decreased left-ventricular function due to ECMO-therapy and therefore, the extent of myocardial edema and hyperemia might be underestimated.

Treatment of cardiogenic shock is still a therapeutic challenge, especially if coronary artery disease was excluded. Usually, sympathomimetics are used as first line therapeutics, but several disadvantages in their use have to be taken into account. Sympathomimetics induced vasoconstriction can lead to perfusion mismatch or even deficit within the microcirculation and metabolic acidosis due to an increased oxygen demand can be observed regularly.[6] In addition, some studies give evidence that use of sympathomimetics is directly linked to enhanced systemic inflammatory response due to an increased interleukin-6 expression.[7,8]

In our case with unclear pathogenesis of cardiogenic shock, we decided to use a mechanical hemodynamic support (intraaortic balloon counterpulsation or ECMO) to avoid above mentioned disadvantages with the use of sympathomimetics, especially with the knowledge about inflammation as a possible cause of 5-FU induced left-ventricular dysfunction. Recently, intraaortic balloon counterpulsation was shown not to reduce 30-day mortality in patients with cardiogenic shock complicating myocardial infarction.[9] In our case with progressive cardiogenic shock, the most effective pre- and afterload reduction was necessary. Therefore, we decided to use ECMO - the most potent form of acute cardiorespiratory support, which enables complete relief of cardiac workload and prevents high-dose usage of sympathomimetics.

CONCLUSION

Cardiogenic shock should be taken into consideration as a possible complication secondary to chemotherapy with 5-FU, even in patients without a history of cardiovascular disease. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first report of an ECMO support in this kind of chemotherapeutic induced cardiogenic shock. ECMO support enabled complete relief of cardiac workload and together with medical therapy for heart failure, complete recovery of cardiac function was possible.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Becker K, Erckenbrecht JF, Häussinger D, Frieling T. Cardiotoxicity of the antiproliferative compound fluorouracil. Drugs. 1999;57:475–84. doi: 10.2165/00003495-199957040-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gianni M, Dentali F, Lonn E. 5 flourouracil-induced apical ballooning syndrome: A case report. Blood Coagul Fibrinolysis. 2009;20:306–8. doi: 10.1097/MBC.0b013e328329e431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Basselin C, Fontanges T, Descotes J, Chevalier P, Bui-Xuan B, Feinard G, et al. 5-Fluorouracil-induced Tako-Tsubo-like syndrome. Pharmacotherapy. 2011;31:226. doi: 10.1592/phco.31.2.226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gianni M, Dentali F, Grandi AM, Sumner G, Hiralal R, Lonn E. Apical ballooning syndrome or takotsubo cardiomyopathy: A systematic review. Eur Heart J. 2006;27:1523–9. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehl032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Röttgen R, Christiani R, Freyhardt P, Gutberlet M, Schultheiss HP, Hamm B, et al. Magnetic resonance imaging findings in acute myocarditis and correlation with immunohistological parameters. Eur Radiol. 2011;21:1259–66. doi: 10.1007/s00330-010-2022-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Schwertz H, Müller-Werdan U, Prondzinsky R, Werdan K, Buerke M. Catecholamine therapy in cardiogenic shock: Helpful, useless or dangerous? Dtsch Med Wochenschr. 2004;129:1925–30. doi: 10.1055/s-2004-831364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Deng MC, Erren M, Lütgen A, Zimmermann P, Brisse B, Schmitz W, et al. Interleukin-6 correlates with hemodynamic impairment during dobutamine administration in chronic heart failure. Int J Cardiol. 1996;57:129–34. doi: 10.1016/s0167-5273(96)02805-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Müller-Werdan U, Jacoby J, Loppnow H, Werdan K. Noradrenalin stimulates cardiomyocytes to produce interleukin-6, indicative of a proinflammatory action, which is supressed by carvedilol. Eur Heart J. 1999;20(Suppl):1721. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Thiele H, Zeymer U, Neumann FJ, Ferenc M, Olbrich HG, Hausleiter J, et al. Intraaortic balloon support for myocardial infarction with cardiogenic shock. N Engl J Med. 2012;367:1287–96. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1208410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]