Abstract

Adoptive cell therapy with chimeric antigen receptor (CAR)-engineered T cells is under investigation as an approach to restore productive T cell immunosurveillance in patients with pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. Early findings demonstrate safety of this cell-based therapy and the capacity of CAR-expressing T cells to mediate anti-tumor activity as well as induce endogeneous antitumoral immune responses.

Keywords: adoptive cell therapy, chimeric antigen receptor, T cell, cancer, pancreas, epitope spreading, immunosurveillance

Pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma (PDAC) is an almost uniformly lethal disease with an 5-yr survival rate that has remained static at ~5% for the past 2 decades despite significant effort. The resistance of PDAC to conventional forms of therapy has spurred investigations into novel treatment modalities, among which are immunotherapeutic regimens.

Leukocytes actively infiltrate the surrounding stromal microenvironment of pancreatic adenocarcinomas. However, tumor-infiltrating leukocytes are dominated by immunosuppressive cells, including macrophages, immature myeloid cells, granulocytes, and regulatory T cells. In contrast, effector T cells are rarely observed to infiltrate tumor tissue.

Immunotherapy has recently demonstrated promise in the treatment of some solid malignancies, such as melanoma, non-small cell lung carcinoma, and renal cell carcinoma.1-3 For example, reversing T-cell immunosuppression by infusion with blocking antibodies that recognize checkpoint molecules, such as cytotoxic T-lymphocyte antigen-4 (CTLA-4) and programmed cell death 1 (PD-1) or its ligand PD-L1, has produced impressive tumor regressions and in some cases, even long-term remissions. However, in the treatment of PDAC, single agent immunotherapy with checkpoint inhibitors, including anti-CTLA-4 and anti-PD-L1 antibodies, has yet to produce objective responses as determined by Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumors (RECIST). 1,4. This finding may be due to a weak naturally occurring antitumor T-cell immune response against pancreatic cancer cells. Consistent with this hypothesis, promising results have recently been reported in PDAC patients with chemotherapy refractory disease by combinatorial treatment with anti-CTLA-4 antibodies and a vaccine designed to induce tumor-specific T cells.5

The induction of productive tumor-specific T-cell immunity is a multi-step process that requires effective processing and presentation of tumor-specific antigens by antigen presenting cells followed by the activation and expansion of tumor-antigen specific T cells. Several mechanisms can limit the productivity of this process leading to ineffective tumor-specific T cell immunity. For this reason, the adoptive transfer of T cells engineered to recognize tumor antigens has garnered recent attention. T cell adoptive therapy is already showing early promise in the treatment of hematologic malignancies.6 However, However, the use of T cell transfer in the treatment of solid malignancies, has been limited partly due to concerns about on-target but off-tumor toxicities.

Mesothelin is a tumor-associated antigen that is overexpressed in the majority of PDAC and has been shown to be a target of an endogenous T cell immune response.7 In preclinical models, mesothelin-specific chimeric antigen receptor (CAR)-engineered T cells have demonstrated potent antitumor activity.8 However, because mesothelin is present on normal peritoneal, pleural, and pericardial surfaces, off-tumor toxicities are possible. To this end, we are currently exploring the use of autologous T cells, referred to as CARTmeso cells, engineered to transiently express (by virtue of mRNA electroporation) a mesothelin-specific CAR that incorporates the T cell receptor CD3ζ and tumor-necrosis factor receptor superfamily, member 9 (TNFRSF9, better known as 4–1BB) signaling domains (clinical trial #NCT01897415 and #NCT01355965).

We recently reported 2 case reports demonstrating the feasibility, safety, and preliminary efficacy of CARTmeso cells.9 No overt evidence for off-tumor toxicities (e.g., peritonitis, pleuritis, and pericarditis) were observed following multiple CARTmeso cell infusions. However, one patient experienced an anaphylactic event when CARTmeso cell therapy was reinitiated after a 4-wk treatment interruption. This adverse event was determined to be most likely the result of patient-derived anti-murine IgE antibodies recognizing the mesothelin-specific CAR that contains murine peptide sequences.10 This finding prompted the modification of ongoing clinical trials evaluating mRNA CARTmeso cell therapy to prohibit infusion interruptions which could allow for IgE class switching.

In one patient with chemotherapy refractory advanced PDAC, we found that mRNA-engineered CARTmeso cell infusion produced a transient metabolic response detected by measuring changes in [18F]-fluorodeoxyglucose (FDG) uptake within tumor lesions detected on positron emission tomography/CT (PET/CT) imaging. In addition, analysis of ascites fluid present throughout treatment revealed a marked decrease in tumor cell burden as measured by fewer cancer cells in the ascites fluid after CARTmeso cell infusion. These findings demonstrate the capacity of CARTmeso cells to mediate antitumor activity. However, stable disease was the best response determined by RECIST 1.1, and disease control was transient with the patient ultimately experiencing cancer progression.

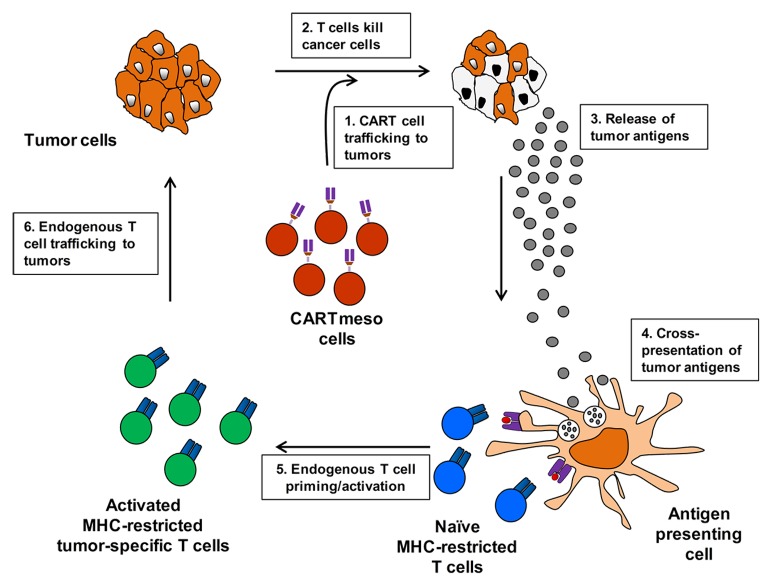

To understand the bioactivity of mRNA-engineered CARTmeso cells, we studied the persistence and trafficking of infused CARTmeso cells in vivo. CARTmeso cells transiently persisted within the peripheral blood after intravenous infusion and were found to traffic to tumor tissue. The transient presence of CAR-engineered T cells was expected based on preclinical data showing a rapid disappearance of CAR expression on T cells following their activation and proliferation.8 Treatment was associated with the development of novel antibodies including transient antitumor immunoglobulin responses. Similar findings were observed for a patient with advanced mesothelioma treated with CARTmeso cell infusions. These findings provide evidence for the capacity of CARTmeso cells to traffic to tumor tissue and facilitate tumor destruction leading to the release of self-proteins including tumor-associated antigens that are then cross-presented in the process of classical epitope spreading (Fig. 1).

Figure 1. Chimeric antigen receptor modified T cell adoptive therapy induces an endogenous antitumor immune response through epitope spreading. Autologous chimeric antigen receptor (CAR)-engineered T cells induce the development of an endogenous antitumor immune response through a multi-step cyclical process as follows: 1) CAR-modified T (CART) cells infiltrate tumor lesions. 2) CART cells recognize tumor antigen expressed on the surface of cancer cells leading to tumor cell lysis. 3) Dying cancer cells release tumor antigens. 4) Tumor-associated proteins are engulfed by antigen presenting cells which process and present tumor-associated peptides in the context of major histocompatibility molecules (MHC) to endogenous T cells. 5) Tumor-specific T cells recognizing peptide/MHC complexes are primed and become activated. 6) Nascent, activated tumor-specific T cells infiltrate tumor lesions. Infiltrating tumor-specific T cells recognize tumor cells via T cell receptor engagement of peptide/MHC complexes present on tumor cells amplifying the initial antitumor T-cell response.

The ability of engineered T cells to stimulate endogenous antitumor immunity suggests that CAR-expressing T cells may also offer a personalized approach for inducing a vaccine effect. However, the success of CAR-engineered T cells may be restrained by immunosuppressive mechanisms present within the tumor microenvironment. As a result, combinatorial approaches incorporating other immunomodulatory strategies, such as immune checkpoint blockade, may be necessary to optimize the full potential of CAR-based T cell immunotherapy in the treatment of PDAC.

In summary, the feasibility, safety, and efficacy of mRNA-modified mesothelin-specific CAR-expressing T cells for the treatment of patients with PDAC, and other mesothelin-expressing advanced solid malignancies, is ongoing. Early clinical findings with CARTmeso cells have demonstrated clinical activity. For this reason, we believe that chimeric antigen receptor-engineered T cells are an attractive approach for the treatment of PDAC and for interrogating immune-resistance mechanisms established by PDAC to evade T cell immunosurveillance.

Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest

G.L.B declares receipt of research funding from Novartis.

Acknowledgments

The author is supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health (K08 CA138907), Department of Defense (W81XWH-12–1-0411), Grant 2013107 from the Doris Duke Charitable Foundation, and the Damon Runyon Cancer Research Foundation for which G.L.B. is the Nadia's Gift Foundation Innovator of the Damon Runyon-Rachleff Innovation Award (DRR-15–12).

Glossary

Abbreviations:

- CAR

chimeric antigen receptor

- CTLA-4

cytotoxic T-lymphocyte antigen-4

- FDG

[18F]-fluorodeoxyglucose

- PDAC

pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma

- PD-1

programmed cell death 1

- PD-L1

programmed cell death 1 ligand 1

- PET/CT

positron emission tomography/computed tomography

- RECIST

Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumors

Citation: Beatty GL. Engineered chimeric antigen receptor-expressing T cells for the treatment of pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. OncoImmunology 2014; 3:e28327; 10.4161/onci.28327

References

- 1.Brahmer JR, Tykodi SS, Chow LQ, Hwu WJ, Topalian SL, Hwu P, Drake CG, Camacho LH, Kauh J, Odunsi K, et al. Safety and activity of anti-PD-L1 antibody in patients with advanced cancer. N Engl J Med. 2012;366:2455–65. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1200694. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Topalian SL, Hodi FS, Brahmer JR, Gettinger SN, Smith DC, McDermott DF, Powderly JD, Carvajal RD, Sosman JA, Atkins MB, et al. Safety, activity, and immune correlates of anti-PD-1 antibody in cancer. N Engl J Med. 2012;366:2443–54. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1200690. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hodi FS, O’Day SJ, McDermott DF, Weber RW, Sosman JA, Haanen JB, Gonzalez R, Robert C, Schadendorf D, Hassel JC, et al. Improved survival with ipilimumab in patients with metastatic melanoma. N Engl J Med. 2010;363:711–23. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1003466. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Royal RE, Levy C, Turner K, Mathur A, Hughes M, Kammula US, Sherry RM, Topalian SL, Yang JC, Lowy I, et al. Phase 2 trial of single agent Ipilimumab (anti-CTLA-4) for locally advanced or metastatic pancreatic adenocarcinoma. J Immunother. 2010;33:828–33. doi: 10.1097/CJI.0b013e3181eec14c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Le DT, Lutz E, Uram JN, Sugar EA, Onners B, Solt S, Zheng L, Diaz LA, Jr., Donehower RC, Jaffee EM, et al. Evaluation of ipilimumab in combination with allogeneic pancreatic tumor cells transfected with a GM-CSF gene in previously treated pancreatic cancer. J Immunother. 2013;36:382–9. doi: 10.1097/CJI.0b013e31829fb7a2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kalos M, June CH. Adoptive T cell transfer for cancer immunotherapy in the era of synthetic biology. Immunity. 2013;39:49–60. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2013.07.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Thomas AM, Santarsiero LM, Lutz ER, Armstrong TD, Chen YC, Huang LQ, Laheru DA, Goggins M, Hruban RH, Jaffee EM. Mesothelin-specific CD8(+) T cell responses provide evidence of in vivo cross-priming by antigen-presenting cells in vaccinated pancreatic cancer patients. J Exp Med. 2004;200:297–306. doi: 10.1084/jem.20031435. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zhao Y, Moon E, Carpenito C, Paulos CM, Liu X, Brennan AL, Chew A, Carroll RG, Scholler J, Levine BL, et al. Multiple injections of electroporated autologous T cells expressing a chimeric antigen receptor mediate regression of human disseminated tumor. Cancer Res. 2010;70:9053–61. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-10-2880. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Beatty GL, Haas AR, Maus MV, Torigian DA, Soulen MC, Plesa G, Chew A, Zhao Y, Levine BL, Albelda SM, et al. Mesothelin-specific Chimeric Antigen Receptor mRNA-Engineered T cells Induce Anti-Tumor Activity in Solid Malignancies. Cancer Immunol Res. 2014;2:112–20. doi: 10.1158/2326-6066.CIR-13-0170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Maus MV, Haas AR, Beatty GL, Albelda SM, Levine BL, Liu X, Zhao Y, Kalos M, June CH. T cells expressing chimeric antigen receptors can cause anaphylaxis in humans. Cancer Immunol Res. 2013;1:26–31. doi: 10.1158/2326-6066.CIR-13-0006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]