Most genetic information is expressed as, and transacted by, proteins. Yet, less than 2% of the human genome actually codes for proteins, prompting a search for functions for the other 98% of the genome, once considered to be mostly “junk DNA.” Transcription is pervasive, however, and high-throughput sequencing has identified tens of thousands of distinct RNAs generated from the non–protein–coding portion of the genome (1). These so-called noncoding RNAs vary in length, but like protein-coding RNAs, appear to be linear molecules with 5′ and 3′ termini, reflecting the defined start and end points of RNA polymerase on the DNA template. But do all RNAs have to be linear?

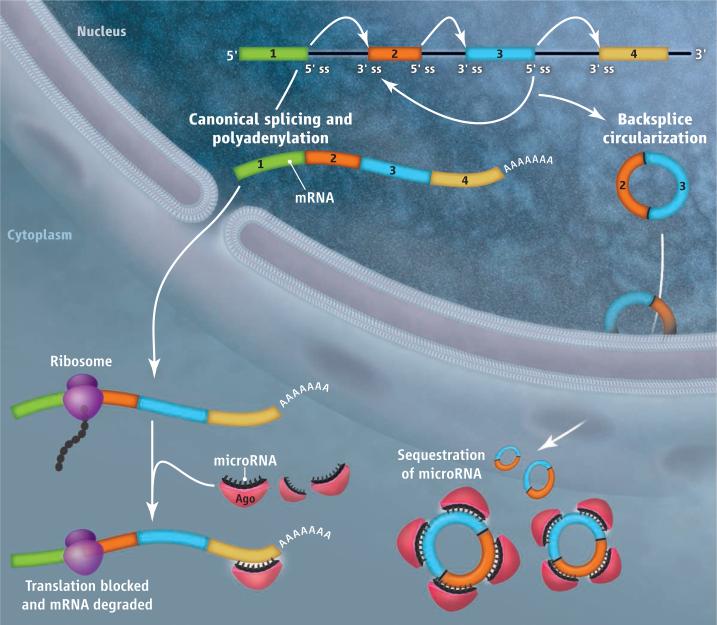

Circular RNAs that have covalently linked ends are found in pathogens such as viroids (virus-like infectious particles), circular satellite viruses, and hepatitis delta virus—which causes severe liver disease in humans infected with hepatitis B and replicates by a rolling-circle–based mechanism (2). A handful of circular RNAs generated from eukaryotic genomes have also been identifi ed (3, 4), but their role is unclear as they are generated by seemingly rare errors in RNA splicing. Because eukaryotes contain split genes, their precursor mRNAs (pre-mRNAs) must be modified such that noncoding introns are removed and protein-coding exons are joined together (see the figure). In these rare cases that generated circular RNAs, the splicing machinery failed to join the 3′ end of one exon to the 5′ end of the next and instead appeared to mis-splice by, for example, joining the two ends of a single exon together. High-throughput sequencing data combined with new computational algorithms (5– 8) have now revealed thousands of circular RNAs in species ranging from humans to archaea.

Circular RNAs sequester microRNAs.

Noncoding introns [flanked by splice sites (ss)] are removed from premRNA by the splicing machinery and a poly(A) tail is added to prevent mRNA degradation (left). Linear mRNA is then translated by ribosomes unless it becomes bound by microRNAs that are associated with argonaute (Ago) protein. The latter interaction inhibits translation and/or promotes mRNA degradation. The splicing machinery can also “backsplice” and generate circular RNAs whose 5′ and 3′ ends are covalently linked (right). Large numbers of these circular RNAs sequester microRNAs from binding mRNA targets.

Human fibroblasts alone have more than 25,000 circular RNAs (5). Derived from ~15% of actively transcribed genes, these circles contain mostly exonic sequences (usually between one and five exons). Large numbers of circular RNAs accumulate in the cytoplasm of cells, sometimes exceeding the abundance of the associated linear mRNA by a factor of 10 (5, 7). This is likely because circular RNAs are resistant to degradation by many cellular RNA decay machineries, which recognize the ends of linear RNAs.

For a subset of circular RNAs, the circularization signals appear to be evolution-arily conserved, as some were detected in both human and mouse (5, 6). The splicing machinery is very likely involved in their biogenesis as canonical splicing signals generally immediately flank their sequences. However, the exact mechanism by which the splicing machinery selects particular regions to circularize is still unclear. The presence of inverted repeats in the surround ing introns and/or exon skipping events may play a role (3, 5, 9).

One particular circular RNA found predominantly in human and mouse brain is ~1500 nucleotides in length and, surprisingly, contains more than 70 evolutionarily conserved binding sites for the microRNA miR-7 (6, 9). MicroRNAs are ~21-nucleotide RNAs that function by base pairing to mRNAs and repressing protein production and/or causing mRNA degradation (10). However, a microRNA can bind to any transcript that contains a complementary sequence and, indeed, this circular RNA may efficiently bind ~20,000 miR-7 microRNAs per cell (6), thereby preventing miR-7 from binding other RNAs. Consistent with a “sponging” model (11), decreasing expression of this circular RNA in cells caused mRNAs containing miR-7 binding sites to also decrease in number, indicative of increased binding of miR-7 to these mRNAs leading to their degradation (6, 9).

Additional circular RNAs may function similarly to regulate the activity of other microRNAs because, in general, microRNA binding sites are abundant in circular RNAs (6). For example, in the mouse, sex-determining region Y (Sry) plays a key role in testes development and generates a circular RNA that contains 16 miR-138 binding sites (9). Circular RNAs thus join a growing class of naturally occurring microRNA “sponges,” which includes competing endogenous RNAs and pseudogene (nonfunctional gene) RNAs (12). Compared to competing endogenous RNAs and pseudogene RNAs, however, circular RNAs are likely much more potent microRNA sponges as they are expressed in greater amounts and contain many more microRNA binding sites. Furthermore, unlike competing endogenous RNAs, circular RNAs appear to be resistant to RNA degradation triggered by microRNAs and thus could have long half-lives (9).

Beyond regulating microRNAs, circular RNAs may bind and sequester RNA-binding proteins or even base pair with RNAs besides microRNAs, resulting in the formation of large RNA-protein complexes. Other circular RNAs may produce proteins, given that synthetic circular RNAs can be efficiently translated (13). As even linear mRNAs are thought to circularize during translation through protein-protein interactions between factors binding the 5′ and 3′ ends of the mRNA, RNA circularization, whether by direct covalent bonds or noncovalent means such as protein bridging or Watson-Crick base pairing, may be much more common than is currently appreciated. The discovery of such a large class of previously unknown RNAs also raises the question of what other RNAs might have been missed. Considering that RNA structural elements, such as triple helices, efficiently prevent degradation from RNA termini (14), it is becoming increasingly clear that the cell uses a myriad of distinct ways to process and stabilize RNA molecules.

A class of circular RNAs that regulates microRNAs is abundant in mammalian cells.

References

- 1.Kapranov P, Willingham AT, Gingeras TR. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2007;8:413. doi: 10.1038/nrg2083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wang KS, et al. Nature. 1986;323:508. doi: 10.1038/323508a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Capel B, et al. Cell. 1993;73:1019. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90279-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cocquerelle C, Mascrez B, Hétuin D, Bailleul B. FASEB J. 1993;7:155. doi: 10.1096/fasebj.7.1.7678559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jeck WR, et al. RNA. 2013;19:141. doi: 10.1261/rna.035667.112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Memczak S, et al. Nature. 2013;495:333. doi: 10.1038/nature11928. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Salzman J, Gawad C, Wang PL, Lacayo N, Brown PO. PLoS ONE. 2012;7:e30733. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0030733. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Danan M, et al. Nucleic Acids Res. 2012;40:3131. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkr1009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hansen TB, et al. Nature. 2013;495:384. doi: 10.1038/nature11993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bartel DP. Cell. 2009;136:215. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.01.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ebert MS, Neilson JR, Sharp PA. Nat. Methods. 2007;4:721. doi: 10.1038/nmeth1079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Salmena L, et al. Pandolfi PP. Cell. 2011;146:353. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.07.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chen CY, Sarnow P. Science. 1995;268:415. doi: 10.1126/science.7536344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wilusz JE, et al. Genes Dev. 2012;26:2392. doi: 10.1101/gad.204438.112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]