Abstract

The remarkable ability of a single axon to extend multiple branches and form terminal arbors allows vertebrate neurons to integrate information from divergent regions of the nervous system. Axons select appropriate pathways during development, but it is the branches that extend interstitially from the axon shaft and arborize at specific targets that are responsible for virtually all of the synaptic connectivity in the vertebrate CNS. How do axons form branches at specific target regions? Recent studies have identified molecular cues that activate intracellular signalling pathways in axons and mediate dynamic reorganization of the cytoskeleton to promote the formation of axon branches.

Introduction

The functions of the vertebrate brain in cognition, learning, memory, sensory perception and motor behaviour require complex neural circuitry. To form this circuitry, individual neurons must connect with multiple synaptic targets, and they do so through extensive branching of their axon and the formation of elaborate terminal arbors1–6. Branches establish topographic maps in numerous systems, including the retinotectal7 and corticospinal systems8, in which regions of the retina and sensorimotor cortex are connected to their targets in the optic tectum and spinal cord, respectively. In addition, multiple branches from the same axon can connect widely divergent regions of the nervous system. For example, single descending cortical axons extend branches into the pons and spinal cord9, single axons from some regions of the thalamus can ramify widely in the somatosensory, motor and higher-order sensory cortices10, and single cortical neurons can send axon collateral branches to homotypic and heterotypic regions of the contralateral cortex11. Cajal, after observing the collaterals of callosal axons, commented: “callosal fibers do not simply join structurally and functionally comparable areas in the two hemispheres. They play a broader role, establishing multiple, complex associations that allow activity in one sensory area to influence a number of areas in the contralateral cerebral hemisphere.”12

Studies of neural development over the past several decades have focused on mechanisms of axon guidance. Surprisingly, given its importance in establishing neural circuits, axon branching has received less attention. How do axon branches form during development? Branches originate as dynamic protrusions that extend and retract from specific locations on the axon. Some of these protrusions become stabilized into branches that arborize by continued re-branching at target sites, leading to synapse formation. Branching is evoked by local extracellular cues in the target region, which signal through receptors on the axonal membrane to activate intracellular signalling cascades that regulate cytoskeletal dynamics. Axon arbors that form within target regions are highly dynamic but eventually stabilize through competitive mechanisms that can involve neural activity.

In this Review, we examine axon branching in the vertebrate CNS. We present in vivo and in vitro findings that illustrate modes of axon branching and the role of extracellular cues in the development of branches and the shaping of terminal arbors. Moreover, we discuss the role of cytoskeletal dynamics at axon branch points and how intracellular signalling pathways regulate cytoskeletal reorganization. Last, we consider the role of activity in regulating axon branching and shaping the morphology of terminal arbors, and identify areas for future research.

Axon branching and arborization

Growth cones, the expanded motile tips of growing axons, respond to extracellular guidance cues to lead axons along appropriate pathways toward their targets13. However, axonal growth cones in the vertebrate CNS do not typically enter their target region. Instead, axons form connections with their target though growth cone-tipped collaterals that branch from the axon shaft and terminal arbors that re-branch from axon collaterals (FIG. 1). In certain circumstances, branches can arise by splitting of the terminal growth cone4,6, such as at the mouse dorsal root entry zone, where the growth cones of dorsal root ganglion (DRG) axons split to form two daughter branches that ascend or descend and arborize in the spinal cord14,15.

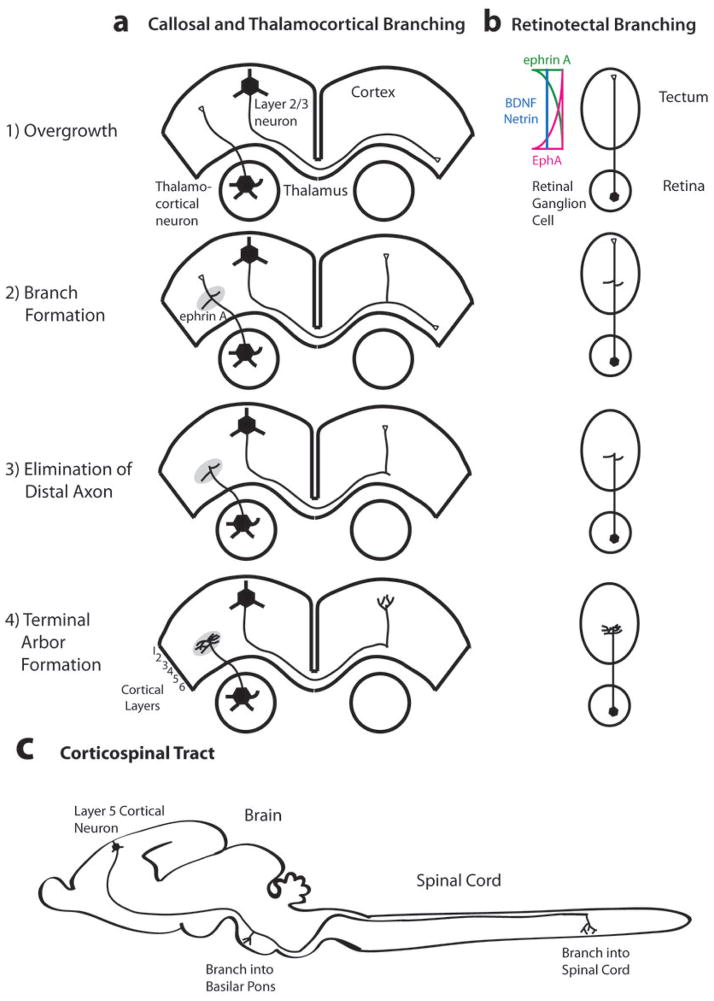

Figure 1. Stages of axon branching in developing CNS pathways.

In the mammalian corpus callosum and thalamocortical pathway (a) and in the chick retinotectal pathway (b), axons initially extend past their eventual terminal regions (1). After a delay, branches extend interstitially from the axon shaft (2) followed by elimination of the distal axon (3) and formation of terminal arbors in topographically correct target regions (4). Figure c depicts interstitial branching from an individual layer 5 sensorimotor cortical axon into the pons and spinal cord (adapted from 9). In the retinotectal system (b), opposing gradients of EPHA–ephrin repellents inhibit retinal axon branching anterior and posterior to the correct target, whereas positive BDNF cues along the tectum promote branching at appropriate topographic positions7, 42. Callosal axons connect homotypic regions of the cortical hemispheres but can also branch to other cortical areas11,12 (not shown). Thalamocortical axons form branches that arborize topographically in layer 4 of somatosensory cortex 23 but other thalamocortical axons can branch into multiple cortical areas19 (not shown).

In the mammalian CNS, axon branches typically extend interstitially, at right angles from the axon shaft behind the terminal growth cone (FIG. 1). This delayed interstitial branching can occur days after axons have bypassed the target16. Cortical axons in rodents initially bypass the basilar pons9, but after a delay, they form filopodia, dynamic finger-like actin-rich membranous protrusions, that can develop into stable branches that arborize in the pons17. Developing corticospinal axons also bypass spinal targets and later form interstitial branches that arborize once they have entered topographically appropriate target sites18. Segments of the axons distal to the target are later eliminated16,19. Callosal axons, which connect the two cerebral hemispheres, also undergo delayed interstitial branching20 beneath their cortical targets, where callosal growth cones collapse and extend repeatedly without advancing forward21. Growth cone pausing and interstitial branching have also been observed in dissociated cortical neurons22 where branches develop from dynamic growth cone remnants that remain on the axon shaft in regions where growth cones paused. Developing thalamocortical axons in vivo form layer-specific lower and upper tiers of terminal arbors in the barrel field, which together form a spatial map of the facial vibrissae in the rodent somatosensory cortex 23. In vivo imaging revealed that branches form de novo along the shaft of the primary thalamocortical axon24 and these give rise to dynamic arbors that extend and retract processes over many days. Thalamocortical axons extend branches at right angles in the target region, showing that interstitial branching is the dominant form of axonal branching in vivo.

In the vertebrate retinotectal pathway, topographic projections maintain spatial information of the visual field from the retina to the tectum. In the avian25 and rodent26 retinotectal systems, retinal ganglion cell axons initially overshoot their termination zone in the tectum and later emit interstitial branches at correct tectal positions, which is followed by terminal arborization and regression of the distal axon7,27 (FIG. 1). However, in frogs and fish, growth cones of retinal axons form arbors as soon as they reach the correct region of the tectum28 and axons do not emit side branches on their way to their targets. Live cell imaging of arbor formation at the tips of retinal axons in the frog optic tectum showed that highly dynamic branches extend and retract repeatedly29. Thus, in the vertebrate CNS, axon branches, rather than the primary axonal growth cone, extend into targets at appropriate locations and thereby establish topographic specificity. Terminal arbors that develop from these branches then undergo dynamic remodeling (FIG. 1).

Role of extracellular cues

Axon branching occurs far from the cell body at localized regions of the axon that are close to the axon’s targets, suggesting that target-derived cues regulate axon branching. Families of extrinsic axon guidance cues, growth factors and morphogens can regulate axon branching by determining the correct position of branches or by shaping terminal arbors2,4.

Guidance cues

Netrins, such as netrin-1, are diffusible guidance cues that attract efferent cortical axons in vivo30–33 and that evoke axon branching in vitro34,35. Focal application of netrin-1 can induce localized filopodial protrusions de novo along the axon shaft34,36 and increase branch length without increasing extension of the primary axon. Netrin-1 also shapes terminal arbors. In the frog optic tectum, injection of netrin-1 enhances development of terminal retinal arbors37 by increasing the dynamic addition and retraction of branches, resulting in an increase in total branch number.

Ephrins are membrane-bound cues that guide axons by repulsion38, 39 and they have a role in specifying the locations of axon branches. In vitro, for example, ephrin-A5 and its receptor (EPHA5) can promote or repress branching of various cortical axons growing on membranes from specific cortical layers40. Ephrin-As stimulate the branching of thalamocortical axons grown on appropriate layer 4 somatosensory cortical membranes41 but they repel axons from limbic regions of the thalamus that do not innervate the somatosensory cortex. Ephrin-As also evoke topographically specific branching of retinal axons in tectal membrane stripe assays25. In vivo, the distribution of EPHAs and ephrin-As in both the retina and in the optic tectum determine the position of retinal axon branches and terminal arbors7 by forward and reverse signalling42. In this system, EPHAs act both as receptors activated by ephrin ligands (forward signalling) and as ligands that activate ephrins (reverse signalling). In a model of retinotectal mapping27, opposing gradients of EPHAs and ephrin-As along the anterior–posterior axis of the tectum inhibit axon branching on the retinal axon segments that are anterior and posterior to the correct target region. A molecule with branch-promoting activity, such as brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF), that was expressed uniformly along the tectum would allow branching in a trough of the repellent gradients43 (FIG. 1). Thus, branching would occur at a unique tectal position for each population of axons based on their temporal or nasal origin in the retina because of their differential sensitivity to the EPHA–ephrin-A repellents. In the dorsal–ventral axis of the tectum, EPHB–ephrinB-1 signalling, perhaps in cooperation with additional cues, regulates topographic mapping of retinal axon branches44. Thus, repression of axon branching is an important regulatory mechanism, since axons must often traverse non-target regions on the way to their targets where additional positive cues may evoke branching.

Semaphorins (protein abbreviation SEMA) are repellent axon guidance cues that function in assembly of neuronal circuits45. For example, SEMA3A repels cortical axons46 and, in vitro, inhibits cortical axon branching34,47, decreasing cortical branch length without affecting the length of the primary axon34. SEMA3D has no effect on the central branches of Rohon-Beard axons in vivo but does repel and induce branching of the peripheral branches of the same axons48. SEMA3A, through its neuropilin–plexin receptors, regulates the pruning of hippocampal axons in vivo and in vitro by selective retraction of transient branches to septal targets49. However, SEMA3A can also positively influence axon branching. Recently, SEMA3A was shown to promote branching by cerebellar basket cell axons onto Purkinje cells in the cerebellar cortex50. In vivo, mice deficient in SEMA3A show layer-specific reductions in terminal branching by basket cell axons and, in vitro, SEMA3A increases the complexity of basket cell axon arbors. Localized signalling mechanisms in basket cell axons50 ensure that SEMA3A promotes specific axon branching without affecting overall axon organization. This might be a general regulatory mechanism whereby molecular cues can influence local branching without affecting axon outgrowth or guidance.

Like semaphorins, SLITs, which act on ROBO receptors, are repulsive cues and they function, for example, in the guidance of commissural axon pathways in the mammalian forebrain51. However, SLITs can also promote the collateral axon branching of mammalian sensory DRG axons in vitro52 and the branching of zebrafish trigeminal axons in vivo53. By contrast, Slit1a inhibits arborization of retinal ganglion cell axons in the zebrafish optic tectum, thereby preventing the premature maturation of terminal arbors54. In this study, in vivo imaging showed that genetic removal of Slit–Robo signalling increases the size and complexity of axon arbors by decreasing branch dynamics and increasing stable branch tips. SLITs, like semaphorins, exhibit context-dependent promotion or repression of axon branching, depending on the particular population of neurons. Moreover, the balance between factors that promote and inhibit arborization may determine final arbor size.

Growth factors

Growth factors, such as fibroblast growth factor (FGF), and neurotrophins, such as nerve growth factor (NGF) and BDNF, can also evoke axon branching and arborization. For example, in vitro, NGF promotes DRG axon branching55,56, BDNF evokes filopodial and lamellipodial protrusions along frog spinal axons57, and FGF-2 and BDNF stimulate branching in cortical axons58,59. In hippocampal slice cultures, BDNF transfection specifically increases axon branching in dentate granule cells60. Moreover, BDNF has been shown to have a prominent role in axon arbor formation in retinal axons in the frog optic tectum61,62. For example, in vivo imaging63 showed that acute BDNF application induces rapid extension of new branches on retinal axon arbors. Thus, target-derived cues shape terminal arbors by regulating the dynamic extension and retraction of their branches. Interestingly, comparisons between the effects of netrin-1 and BDNF on retinal arbors37 suggest that although both factors increase arbor complexity, BDNF promotes the addition and stability of axon branches whereas netrin-1 induces new branch growth but not branch stabilization. Different cues can, therefore, produce a similar outcome on final arbor morphology by different dynamic strategies.

Morphogens

WNTs comprise a diverse family of secreted morphogens that shape embryonic development. Several WNTs also function as axon guidance cues64,65 or regulate axon branching. For example, WNT7A66, secreted by cerebellar granule cells, induces remodeling of pontine mossy fibre axons by inhibiting their elongation, enlarging their growth cones, inducing spreading of regions along the axon shaft and consequently increasing axon branching. WNT3A, secreted by motor neurons, regulates terminal differentiation in a subset of presynaptic arbors of spinal sensory neurons by inducing axon branching67,68, whereas WNT5A, a repulsive axon guidance cue for cortical axons in vivo69–71, increases the elongation of cortical axons and branches72 but not the numbers of axon branches73. However, WNT5A increases axon branching of developing sympathetic neurons acutely and over the long term also enhances axon extension74.

These findings suggest that extracellular cues can promote or repress axon branching without affecting the growth and guidance of the parent axon. Differences between local signalling and cytoskeletal mechanisms at the growth cone and along the axon shaft could account for different effects of the same molecule on axon guidance, elongation and branching.

Reorganization of the cytoskeleton

The initiation, growth and guidance of axon branches in response to extracellular cues require regulation of actin and microtubule dynamics (FIG. 2), which share similarities5,75,76 with cytoskeletal dynamics during growth cone navigation75,77–79. Filopodial and lamellipodial protrusions along the axon serve as precursors to branches. Filopodia contain long unbranched bundled actin filaments, whereas lamellipodial veils contain a meshwork of branched actin filaments. An initial step in branch formation is the focal accumulation of actin filaments at axon membrane protrusions34,80. Filopodia can emerge from transient accumulations of actin filaments (termed actin patches) on sensory axons81–83, although only a fraction of actin patches gives rise to axonal filopodia3.

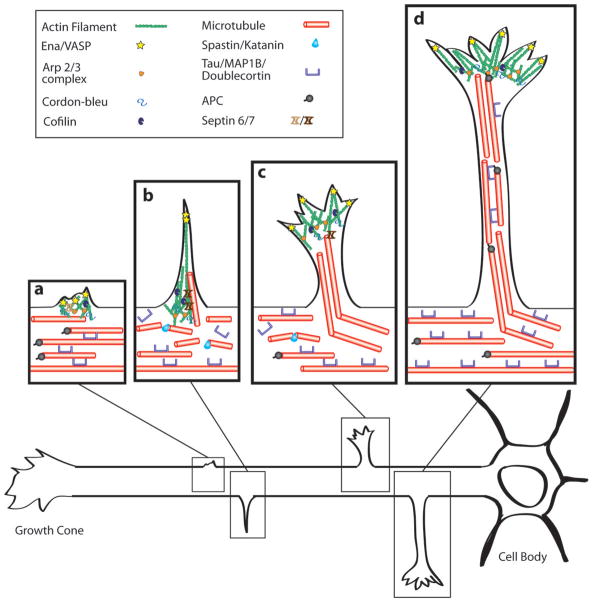

Figure 2. Cytoskeletal reorganization at different stages of axon branching.

a | Membrane protrusion requires the accumulation of actin filaments, which can form patches81–83. In (a) membrane protrusion requires actin nucleation (ARP2/382,83 and Cordon-bleu88), actin branching (ARP2/3) and actin elongation (Ena/VASP)35. Cofilin is important for the turnover of actin filaments92 and Septin 6 is localized to the actin patch110. MTs are stabilized by MAPs (Tau//Doublecortin)78,99,103 in the axon but are also capable of extending at their plus ends (APC/EB proteins)100,101. b | Filopodia, which contain bundled actin filaments, emerge from the axon shaft accompanied by localized splaying and fragmentation of MTs55,80,93,96,97; these invade the filopodium and extend along actin bundles. MTs are severed by Spastin and Katanin98. Septin 7 promotes the entry of MTs into the filopodium110. c, d | Stable MTs enter the nascent branch (c), which continues to mature and extend; this growth is led by a motile growth cone (c, d). MAPs protect some of the MTs in the axon shaft from severing (c, d). Within the axon branch MTs become bundled and stabilized by MAPs (d).

Actin dynamics

Actin filaments are polymers with barbed ends, facing the plasma membrane, where actin monomers are added and pointed ends, facing away from the membrane, where actin filaments disassemble. Membrane protrusion and motility are driven by dynamic cycles of actin polymerization and depolymerization77,78. In growth cones and filopodia, actin filaments undergo continual cycles of retrograde flow and polymerization84. The balance between these two processes determines whether membrane protrusions extend or withdraw.

Actin arrays and dynamics are highly regulated by actin-associated proteins, which have important roles in axon guidance and branching77 (FIG. 2). For example, Ena/VASP proteins (enabled/vasodilator-stimulated phosphoprotein) bind to the barbed ends of actin filaments and enhance actin filament elongation by antagonizing the capping proteins that inhibit F-actin elongation85. When Ena/VASP proteins are sequestered to the mitochondria in hippocampal neurons, the axons of these neurons have fewer filopodia containing fewer actin filament bundles35. Interestingly, Ena/VASP depletion in frog retinal ganglion neurons reduces filopodial formation, retinotectal axon branching and arborization in the tectum in vivo86. The formins, which nucleate (i.e. promote the formation of actin filaments de novo, rather than adding to existing filaments) actin filaments at barbed ends, are essential in neurite initiation and the formation of filopodia. In cortical neurons lacking Ena/VASP, filopodia can be restored by ectopic expression of the formin mDIA2 87. A recently identified actin nucleator, cordon-bleu88, promotes actin polymerization of unbranched filaments and, when overexpressed in hippocampal neurons in vitro, increases axon branching without affecting axon length. Actin-related protein 2/3 (ARP2/3) nucleate new branched filaments from the sides of existing actin filaments77 and are required for NGF-induced actin patches, filopodia formation and branching of sensory axons82,83. One study has shown that ARP2/3 depletion in hippocampal neurons89 reduces filopodial and lamellipodial dynamics, although another study90, using a dominant negative approach to inactivate ARP2/3, saw no decrease in axonal filopodia.

Dynamic axonal filopodia not only protrude but also withdraw. Gelsolin severs actin filaments and caps free barbed ends and its depletion in hippocampal neurons increases filopodia through reduced retraction91. The actin-severing protein family ADF/cofilin increases actin filament depolymerization but it also promotes filament assembly by increasing the available pool of actin monomers and free barbed ends. Thus, ADF/cofilin activity contributes to BDNF-induced filopodia on retinal growth cones92. Myosin II, a motor protein involved in actomyosin contraction of antiparallel filaments, drives retrograde actin flow and aids in disruption of F-actin networks84. Although the exact role of many actin-associated proteins remains to be determined in vertebrate axon development, dynamic remodeling of the actin cytoskeleton during cycles of polymerization and depolymerization is an essential event in the initiation of branches by filopodia and lamellipodia as they probe the extracellular environment.

Microtubule dynamics

Actin filament polymerization is essential for the pushing force that drives membrane protrusion but further development and stabilization of axon branches require the entry of dynamic microtubules (MTs) into filopodia5,93. MTs are hollow tubular structures that comprise linear arrays of α and β tubulin78,94. In growth cones and developing branches, the MT ‘plus’ ends, where tubulin dimers are added and subtracted, face outward toward the membrane, whereas MTs are generally stabilized at their minus ends, which are oriented away from the membrane. MTs undergo dynamic instability95 that results in continuous cycles of growth and shrinkage at their plus ends. These cycles of polymerization and depolymerization enable MTs to reorganize and explore the growth cone periphery and extend into developing axon branches. MTs in axons are organized in stable parallel bundles, so important early steps in axon branch formation are the splaying of bundled MTs, their local fragmentation at axon branch points followed by entry of short MT fragments into filopodia. This dramatic MT reorganization, observed in chick sensory axons as well as rodent hippocampal and cortical neurons55,80,93,96,97 leads to stabilization of elongating axon branches containing MTs. As shown by time lapse imaging, only those filopodia that contain MTs develop into branches93, although even long branches containing MTs can eventually retract.

How are MT dynamics and organization regulated during axon branch formation? Microtubule-associated proteins (MAPs) — such as stabilizing, plus-end-tracking, severing, destabilizing and motor proteins — have roles in growth cone steering77,78,94 and some of these MAPs have also been investigated for a role in axon branching. For example, overexpression of MT severing proteins (either spastin or katanin), in cultured hippocampal neurons, increase axon branching98, while depletion of either protein reduces axon branching. Interestingly, tau, a MAP that stabilizes MTs against depolymerization, protects MTs against the severing effects of katanin, so that when tau is depleted axon branching is increased99. This suggests that detachment of tau from MTs might be a mechanism for regulating branch formation. One possibility is that as short MT fragments enter nascent branches, structural MAPs such as MAP1B, which also interacts with actin filaments78, could stabilize them.

Further growth of MTs at their dynamic plus ends is regulated by a family of plus-end tracking proteins (+TIPs), such as the end-binding proteins EB1 and EB3 and adenomatous polyposis coli protein (APC), which contribute to MT elongation and axon outgrowth100. WNT3A-induced remodeling of DRG axons68 — comprising a decrease in the growth rate of the axon and increases in branching and growth cone size — results from changes in the directionality of MTs that lead to MT looping; such looping has also been observed in large paused cortical growth cones80,93. Since WNT3A decreases the levels of APC, APC is thought to have a role in determining the direction of MT growth, although exactly how this contributes to regulation of axon branching is unclear. APC-deficient mice in vivo show severe misrouting of cortical axons and, in vitro, cortical axons lacking APC show excessive axon branching, which is caused by MT instability and disruption of MT organization at branch points101. The growth cones of APC-deficient cortical neurons frequently split to produce multiple branches102, and this results from MT splaying and disorganization. Deletion of the gene encoding doublecortin (DCX), another MAP, not only causes migratory defects in adult mouse forebrain neurons but also evokes excessive branching of the primary neurite103, which was attributed to a failure in the maintenance of MT cross linking. The MT-destabilizing kinesin, KIF2A, also has a role in axon branching104. Hippocampal and cortical neurons in vivo and in vitro from mice lacking KIF2A have abnormally long axon collateral branches that form more secondary and tertiary branches. Concomitantly, in neurons lacking KIF2A, MT-depolymerizing activity is diminished, suggesting that KIF2A normally suppresses collateral growth. These results emphasize the importance of regulated cytoskeletal dynamics in repressing axon branching during the development of neural circuitry.

Actin–microtubule interactions

Neither actin filaments nor MTs act alone during the formation of axon branches. Dynamic MTs and actin filaments are thought to interact bidirectionally in growth cone motility78,105, as dynamic MTs extend along and copolymerize with actin filaments in the growth cone periphery80,106,107. Actin–MT interactions are also essential for branch formation, as MTs extend into filopodia along actin filament bundles (FIG. 2). Thus, drugs that attenuate the dynamics of either actin filaments or MTs inhibit branch formation but not extension of cortical axons in vitro80. Mechanisms that link actin filaments and dynamic MTs may have implications for axon branch formation. For example, in cultured cortical neurons, the interaction between the F-actin-associated protein drebrin and EB3 occurs at the base of filopodia, which is important for the exploration of filopodia by MTs during neuritogenesis108. Genetic ablation of ADF/Cofilin in cortical and hippocampal neurons, disorganizes the actin network and impairs MT bundling and protrusion into filopodia, leading to inhibition of neurite initiation109. Since ADF/Cofilin regulates actin retrograde flow by actin disassembly and turnover, the ability of MTs to coalesce and form neurites was thought to depend on actin retrograde flow driven by actin-severing proteins. In this study, the authors concluded that MTs follow the lead of dynamic actin filaments. Coordination of actin and MT dynamics is also required for axon branching in chick DRG neurons and mammalian hippocampal neurons. For example, branch formation in sensory axons involves several septin proteins that interact with both cytoskeletal components110. SEPT6 localizes to actin patches and recruits cortactin, an ARP2/3 regulator, to trigger formation of filopodia, whereas SEPT7 promotes the entry of axonal MTs into filopodia, enabling branch formation through as yet unknown mechanisms. It seems likely that future studies will reveal additional molecules that coordinate reorganization of the actin and MT cytoskeletal to promote development of axon branches.

Signalling pathways

During axon pathfinding, the growth cone must interpret and integrate numerous extracellular cues simultaneously through activation of multiple signal transduction pathways111,112. Some of these pathways also regulate axon branching. RhoGTPases78,113 and the protein kinase glycogen synthase kinase 3β (GSK3β)114–117 have emerged as signalling nodes that regulate actin and MT dynamics through multiple extracellular cues and cytoskeletal effectors. Although no single pathway from receptor to the cytoskeleton has been completely defined, we will present several examples of signalling pathways that regulate axon branching (FIG. 3).

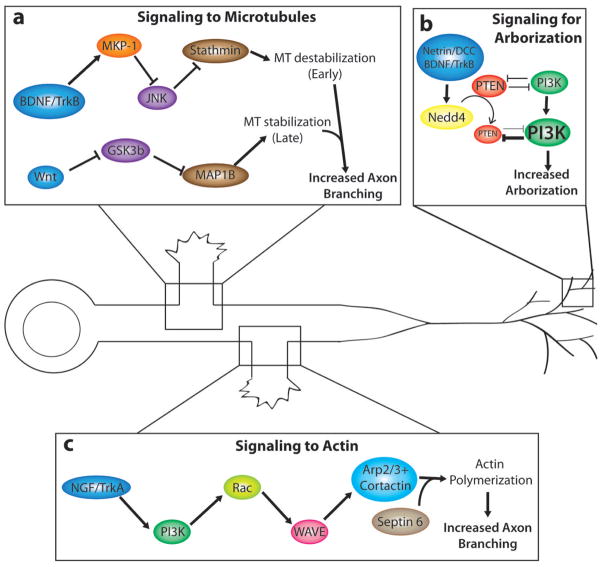

Figure 3. Signalling pathways that promote axon branching.

a | Different pathways leading to MT destabilization (top) at early branching stages or by MT stabilization at later branching stage (bottom) can each promote axon branching by opposing effects on MT stability. Differential effects on MT stability are shown in two examples of branching induced by BDNF and its TRKB receptor (top) in cortical neurons58 or the morphogen WNT7A (bottom) in pontine mossy fibers66,120 b | BDNF and netrins increase terminal arborization of frog retinotectal axons37, 63. In this signalling pathway123, NEDD4 ubiquitinates PTEN and PTEN degradation leads to increased terminal axon branching by promotion of PI3K, which is known to regulate cytoskeletal dynamics. By contrast, inhibition of NEDD4 leads to an increase in PTEN levels and hence inhibition of axon branching. c | NGF-induced TRKA signalling promotes axon branching in chick sensory (DRG) axons82. It does this by activating PI3K and, in turn, RAC, which activates actin associated proteins to increase actin polymerization and the formation of actin patches. Cortactin, recruited by Septin6, promotes the emergence of filopodia from actin patches. Abbreviations: brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF), mitogen activated protein kinase phosphatase (MKP-1), MAPK c-jun N-terminal kinase (JNK), stathmin (STMN), phosphoinositide 3-kinase (PI3K), ubiquitin ligase E3 (NEDD4), the phosphatase phosphatidylinositol 3,4,5 trisphosphate (PTEN), nerve growth factor (NGF), actin related protein (ARP 2/3).

NGF promotes the formation of filopodia and branches in chick sensory axons55 by increasing the number of actin patches through an increase in the rate of patch formation81. This effect is driven by phosphoinositide 3-kinase (PI3K)82,83 and requires the actin nucleating complex ARP2/3. In a model of the NGF signalling pathway82, the NGF receptor TRKA activates PI3K, which in turn activates RAC1 to drive activity of WAVE1 that activates ARP2/3. The actin-associated protein cortactin, which stabilizes branched actin filaments nucleated by ARP2/3118, does not regulate actin patch formation but promotes the emergence of filopodia from actin patches. Cortactin is also involved in axon branching119 by promoting actin polymerization and membrane protrusion. In hippocampal neurons, calpain, through proteolysis of cortactin, represses actin polymerization and maintains the neurite shaft in a consolidated state, which can be de-repressed by factors such as netrin-1 and BDNF to permit branching. These examples illustrate how actin-nucleating proteins and associated stabilizers regulate specific steps in branch formation as well as suppression of axon branching.

BDNF induces axon branching of mouse cortical neurons through its receptor TRKB. Recently, negative regulation of mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) by the MAPK phosphatase MKP-1 was shown to have a role in BDNF-induced cortical axon branching58. MAPK is also involved in cortical axon branching downstream of netrin-1-induced calcium signalling36. In vivo overexpression or down regulation of MKP-1 in layer II–III cortical neurons increases or decreases their terminal axon branching, respectively, in the contralateral cortex. MKP-1 is induced transiently at sites of BDNF activity and inactivates the MAPK c-jun N-terminal kinase (JNK) by dephosphorylation, which in turn reduces the phosphorylation of the JNK substrate stathmin-1 (STMN1), thereby activating STMN1. This study also showed that MKP-1 overexpression increased tyrosinated tubulin (associated with dynamic MTs) and decreased detyrosinated and acetylated tubulin (associated with stable MTs). Since STMNs destabilize MTs94, in this model58, the authors propose that activating STMNs through BDNF signalling destabilizes MTs and, consequently, increases cortical axon branching (FIG. 3).

In other models of axon branching, extracellular cues have been shown to regulate axon branching by influencing MT dynamics through GSK3β signalling. For example, WNT7A66 induces filopodia and spread regions along the axon shaft of pontine mossy fibres where stable MTs become unbundled120, leading to increased axon branching. WNT7A inhibits GSK3β activity, which normally phosphorylates MAPs such as tau, APC and MAP1B65. Activation of the WNT pathway therefore decreases MAP1B phosphorylation. Since phosphorylated MAP1B maintains MTs in a dynamic state121, decreased MAP1B phosphorylation would increase MT stability, leading to terminal remodeling of mossy fibres and axon branching. This seems to contradict results showing that axon branching is dependent on pathways that destabilize MTs58. However, axon branching initially involves destabilizing MTs at branch points (FIG. 2) but further growth of branches requires entry of stable MTs into the nascent branch. GSK3β has also been shown to function in a novel signalling pathway that inhibits axon branching of granule cell neurons in the rodent cerebellar cortex122. In this study, knockdown of the JNK-interacting protein kinase 3 (JIP3) stimulates granule cell interstitial axon branching by decreasing levels of GSK3β. Suppression of axon branching by JIP3–GSK3β signaling involves phosphorylation of a novel GSK3β substrate, DCX. However, the downstream cytoskeletal mechanisms by which the JIP3–GSK3β–DCX signalling pathway actively suppresses axon branching are unknown. Manipulation of GSK3s α and β levels and its association with different MAP substrates in DRG and hippocampal neuronal cultures117 have led to various outcomes on axon outgrowth and axon branching, highlighting the complexity of GSK3 function in the regulation of MT organization and dynamics.

Netrin-1 and BDNF regulate terminal branching of retinal axons in the frog optic tectum37,63. A recent in vivo study123 identified a signalling pathway involving the ubiquitin-protein ligase E3 NEDD4 and the phosphatase phosphatidylinositol 3,4,5- trisphosphate (PTEN) that negatively regulates the PI3K signalling pathway (FIG. 3). Inhibition of NEDD4 increases the levels of PTEN, resulting in simple sparsely branched retinal axon arbors in the tectum but no effect on axon navigation. Thus, PTEN overexpression inhibits axon branching, whereas PTEN knockdown restores axon branching. In this study, the authors proposed that, in response to external signals, NEDD4 ubiquitinates PTEN, thereby targeting it for degradation, which promotes the PI3K pathway and the downstream cytoskeletal reorganization that leads to axon branching. Importantly, this study shows how signalling pathways can specifically regulate terminal branching without affecting long-range axon pathfinding.

Activity-dependent mechanisms

Neuronal activity can also regulate axon branching (FIG. 4). Spontaneous electrical activity during early development124 generates transient fluctuations in intracellular calcium, an essential second messenger. Calcium transients, activated by cues such as netrin-1 and BDNF in neuronal growth cones, regulate axon outgrowth and guidance125 by signalling to downstream effectors such as calcium/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II (CaMKII) and the calcium/calmodulin-dependent phosphatase calcineurin that ultimately regulate the growth cone cytoskeleton. Calcium signalling also has an important role in axon branching. For example, local application of netrin-1 to cortical axons in vitro36 increases the frequency of calcium transients in small regions of the axon and simultaneously evokes rapid localized filopodial protrusion and axon branching through CaMKII and MAPK activation. Thus, local Ca2+ transients can promote branching within discrete regions of the axon.

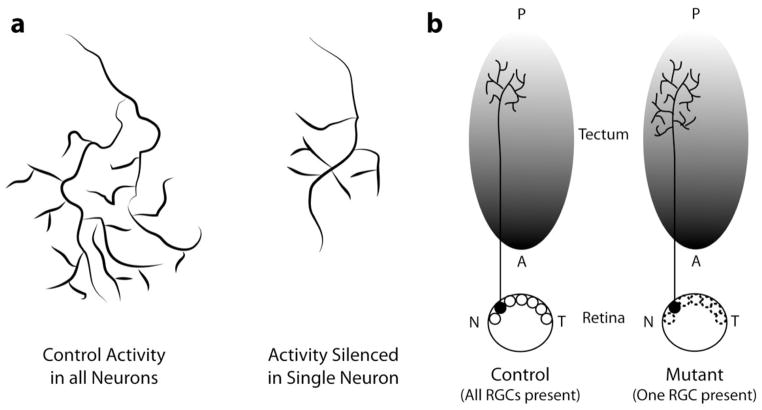

Figure 4. Competition shapes the morphology of terminal arbors.

a | The terminal arbor of a retinal axon in the zebrafish optic tectum with normal electrical activity has a complex highly branched morphology (left), and it can outcompete a neighbouring retinotectal arbor in which electrical activity has been silenced (right), resulting in a smaller less elaborate morphology in the silenced axon134. b | A retinal axon arbor in a normal control zebrafish tectum (left) has a smaller less complex morphology when all other retinal gangion cells (RCGs) are present. In the mutant zebrafish with only a single RCG axon (right), arbors terminate in appropriate tectal regions but are larger and more complex in the absence of competitive interactions with neighboring axons (figure adapted from 136). Anterior posterior tectum (A, P), nasal temporal retina (N, T).

Downstream of calcium activity and activation of CaMKII, which acts as an intracellular calcium sensor, the Rho family of small GTPases regulates actin filament assembly and organization in growth cones78,125. The RhoGTPase RhoA has also been shown to have an important role in cortical axon branching126. In this study branching of horizontal axons arising from upper layer cortical neurons, was observed in cortical slices where introduction of constitutively active RhoA increased axon branching through increased dynamic addition and loss of branches while RhoA inhibition decreased branching. Blockade of neural activity decreased active RhoA, suggesting that RhoA is a positive regulator of activity dependent axon branching in cortical neurons. This is only one possible regulator of activity-dependent axon branching, and further study will be required for understanding molecular mechanisms that mediate activity-dependent processes.

Branches can extend while their axons stall or retract19. In vivo, axons and branches are likely to encounter different types or concentrations of factors that evoke different levels of Ca2+ activity, which could independently regulate the outgrowth of different processes from the same axon. For example, in NGF-mediated axon outgrowth of sympathetic neurons, axon branches that are depolarized to induce calcium entry are favoured for growth at the expense of unstimulated branches of the same axon127. In cortical neurons, imposition of Ca2+ activity in an axon versus its branches, causes a process with higher frequency Ca2+ transients to grow faster at the expense of another process with lower levels of Ca2+ activity that stalls or retracts128. How growth of one axonal process is coordinated with retraction of another is unknown.

Activity-dependent mechanisms are also important in shaping terminal axon arbors129,130. For example, patterned neural activity in the frog retinotectal pathway shapes the morphology of retinal axon arbors by governing axon branch dynamics131. Callosal axons in mice expressing an inward rectifying potassium channel to suppress neural activity extend through the contralateral cortex with little branching and end in immature growth cone-like structures132. Similarly, suppression of spontaneous firing of thalamic or cortical neurons in organotyptic co-cultures reduces thalamocortical axon branching133. Conversely, neural activity enhances the branch dynamics of thalamocortical axons that are biased toward branch addition and elongation in cortical target layers134.

The effects of neural activity can also involve competition among neighbouring axon arbors. For example, in the zebrafish retinotectal system135, silencing electrical activity in one axon relative to neighboring axons reduces the size of the terminal arbor of the ‘silenced’ axon (FIG. 4). Arbor size and complexity of the neuron with reduced activity is restored when activity of neighboring axons is silenced, demonstrating a competitive activity-dependent mechanism. However, another study in the zebrafish retinotectal system136 showed that singly silenced axons have larger than normal arbors, although silencing neighbouring axons also restores normal arbor size to the activity-suppressed axon. In this study suppression of presynaptic activity in retinal ganglion cells and live cell observations of axon arbor formation over days showed that presynaptic activity is not required for development of arbors with an appropriate number of stable branches. However, presynaptic activity is required for arbor maturation, as shown by increased production of dynamic filopodia. These results suggest that activity normally arrests formation of filopodia during arbor maturation. Moreover singly silenced axons fail to arrest growth of branches, leading to expansion of the arbor territory on the tectum. Restoration of normal arbor size by silencing of neighboring retinal axons demonstrates that, although the cellular mechanisms underlying the competition are unknown, the ability of axons to arrest their growth is an activity-dependent competitive process. To further demonstrate effects on axon arbors in the absence of competition, zebrafish with a single retinal ganglion cell were created137. Arbors of this single axon terminate in appropriate tectal regions but are larger and more complex than normal. Although an understanding of the exact mechanisms requires further study, these examples show the importance of competitive interactions in shaping axon terminal arbors.

Conclusions and future directions

Over the past decade, we have gained significant insight into mechanisms that regulate axon branching. The discovery of new branching mechanisms, such as the kinase signalling pathway that controls immobilization of mitochondria at nascent presynaptic sites to regulate cortical axon branching138, will continue to expand and modify our understanding of axon branching. However, many issues remain unresolved. First, we still lack a complete understanding of why individual axons branch only at specific target locations. The presence of gradients of molecular cues and the suppression of inappropriate branching have been postulated as mechanisms that underlie the specificity of branching in the retinotectal system7 but whether these apply more generally to vertebrate systems will require further study. Second, although the cytoskeleton is the final target for the convergence of signalling pathways, we still lack a clear understanding of how the consolidated axonal cytoskeleton is transformed into dynamic MTs and actin filaments that drive membrane protrusion at axon branch points. The improvements in genetically encoded labeling techniques and high resolution time lapse microscopy should now make it possible to observe longer term cytoskeletal reorganization and dynamics that occur at specific stages of axon branching (BOX 1). Third, to understand mechanisms of axon branching in vivo, it will be important to investigate signalling events and cytoskeletal changes during branching in preparations of the CNS such as slices or explants that recapitulate the complex in vivo environment. These approaches can be combined with genetic manipulations of signalling components and cytoskeletal effectors. It is clear from this review that our understanding of how signalling pathways transduce effects of extracellular cues on the axonal cytoskeleton to promote axon branching is at an early stage. At present, it is unclear how the same guidance cue can have different effects on branching in different neuronal populations or differentially affect growth of an axon and branches of the same neuron. In future studies, it will be important to connect intracellular signalling to its effects on cytoskeletal dynamics at branch points in living neurons of different types. Moreover, mechanisms for suppression of axon branching to create topographic specificity are poorly understood. Live cell imaging has provided an exciting window into dynamic remodeling of axon terminal arbors in vivo and it will be important in revealing how electrical activity through calcium signalling regulates arbor formation and competitive interactions among neighbouring axons in a target region. Addressing such questions with new techniques over the next decade will inform our understanding of the remarkable ability of a single axon to branch into specific regions of the developing nervous system.

Box 1. New technologies for studying axon branching.

Much of the organization of axon branch points is obscured because the small diameter and cylindrical structure of the axon. Many of the live-cell imaging studies of cytoskeletal dynamics at branch points and the growth cone described in this review have employed transfection of neurons with plasmids encoding fluorescent fusion proteins, such as enhanced green fluorescent protein (EGFP) and mCherry fused to cytoskeletal components such as actin and tubulin. To visualize fluorescently labeled actin filaments and microtubules and their associated proteins many investigators are currently using high resolution microscopy such as total internal reflection fluorescence (TIRF) microscopy and spinning disk confocal microscopy. However, new advances in imaging — specifically structural illumination microscopy (SIM)139, stimulated emission depletion (STED) microscopy140, photoactivated localization microscopy (PALM)141 and stochastic optical reconstruction microscopy (STORM)142 — will allow future studies of cytoskeletal dynamics and signalling at branch points at resolutions on the order of tens of nanometers. Importantly, all of these imaging techniques can be used on living samples. The study of axon branching would also greatly benefit from the availability a greater diversity of ‘caged’ proteins and compounds, so that local uncaging could be performed at specific sites along an otherwise consolidated axon, in a similar way to the uncaging of neurotransmitters at individual dendritic spines. Optogenetic control over genetic or functionally defined populations of or individual neurons will undoubtedly allow much more sophisticated experiments on the role of activity in axon branching at high temporal and spatial precision141. Such techniques would also allow researchers to test the role of activity in individual branches or arbors of the same neuron. To understand axon branching, it is also important to reconstruct, with high precision, the full extent of an axon arbor. In the past, this has required laborious thin section and/or electron micrograph reconstruction. The recent advent of tissue clearing techniques, such as ScaleA2 143, CLARITY144, SeeDB 145 and ClearT/T2 146, which allow fluorescently labeled axons and branches to be reconstructed in their full extent, will help in understanding how axon branching is affected in normal, transgenic and disease models.

Acknowledgments

We apologize that, owing to space constraints, we could not cite many excellent studies. We thank members of our laboratories for reviewing the manuscript and the helpful comments of the anonymous reviewers. Work from our laboratories is supported by US National Institutes of Health grants NS014428, NS064014 and NS080928.

Nature Reviews glossary

- 1. terminal arbor

The highly branched tree-like structure at the end of an axon that innervates target regions

- 2. collateral branch

A branch that extends from the sides of an axon, often interstitially, that can innervate a target by re-branching to form a terminal arbor

- 3. cytoskeletal dynamics

Cycles of polymerization and depolymerization resulting in growth and shrinkage of microtubules and actin filaments allowing their reorganization

- 4. forward and reverse signaling

EPHAs act both as receptors activated by ephrin ligands (forward signaling) and as ligands that activate ephrins (reverse signaling)

- 5. neurotrophic factor

Molecules such as BDNF and NGF that regulate neuronal growth and survival

- 6. lamellipodium

A thin sheet like veil of cytoplasm at the growth cone periphery comprised of actin filament networks

- 7. filopodium

A finger like membrane protrusion containing bundled actin filaments. Filopodia extend transiently from the growth cone, the axon shaft and from axon branches

- 8. +TIPS

Plus end tracking proteins such as EB1 and EB3 that associate with the growing plus ends of dynamic microtubules

- 9. RhoGTPases

A family of molecules that regulate cytoskeletal dynamics downstream of guidance cue receptors

- 10. calcium transient

A transient elevation in the level of intracellular calcium that can occur repetitively at different frequencies

Biographies

Katherine Kalil received her Ph.D at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Cambridge, USA, and has spent her research career at the University of Wisconsin-Madison, USA, where she is a professor in the Department of Neuroscience. Her research focuses on cytoskeletal and signaling mechanisms in axon growth and guidance.

Erik Dent received his Ph.D at the University of Wisconsin-Madison, USA, and conducted postdoctoral training in the Department of Biology at Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Cambridge, USA. He returned to Madison and is now an Associate Professor in the Department of Neuroscience at the University of Wisconsin-Madison, USA. His research focuses on the actin and microtubule cytoskeleton in neuronal development and plasticity.

Nature Reviews Online Summary

Axon branching connects single neurons with multiple targets, which, along with the formation of highly branched terminal arbors, underlies the complex circuitry of the vertebrate CNS.

Axon collateral branches extend interstitially from the axon shaft as dynamic filopodia that develop into branches at appropriate targets regions to form functional maps. Extrinsic guidance cues, growth factors and morphogens regulate axon branching and shape terminal arbors that develop from axon branches.

Growth and guidance of axon branches in response to extracellular cues require dynamic reorganization of the actin and microtubule cytoskeleton. Cycles of cytoskeletal polymerization and depolymerization are highly regulated by actin and microtubule associated proteins during branch formation.

Complex signaling pathways activated by extracellular cues through their receptors regulate axon branching. The ultimate target of signal transduction pathways is the cytoskeleton, which can reorganize by changes in dynamics to promote or suppress axon branching.

Neuronal activity, often stimulated by extracellular cues, can regulate axon branching by transient fluctuations in intracellular calcium that acts as a second messenger to activate downstream cytoskeletal effectors. Effects of neural activity can involve competition among neighboring axon arbors such as in the retinotectal system where competitive activity-dependent mechanisms regulate arbor size and complexity.

Future directions in the study of axon branch formation will involve the use of preparations of the vertebrate CNS that recapitulate the complexity of the in vivo environment. Improvements in labeling techniques and high resolution time-lapse microscopy should facilitate such studies.

References

- 1.Acebes A, Ferrus A. Cellular and molecular features of axon collaterals and dendrites. Trends Neurosci. 2000;23:557–65. doi: 10.1016/s0166-2236(00)01646-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bilimoria PM, Bonni A. Molecular control of axon branching. Neuroscientist. 2013;19:16–24. doi: 10.1177/1073858411426201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gallo G. The cytoskeletal and signaling mechanisms of axon collateral branching. Dev Neurobiol. 2011;71:201–20. doi: 10.1002/dneu.20852. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gibson DA, Ma L. Developmental regulation of axon branching in the vertebrate nervous system. Development. 2011;138:183–95. doi: 10.1242/dev.046441. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kornack DR, Giger RJ. Probing microtubule +TIPs: regulation of axon branching. Curr Opin Neurobiol. 2005;15:58–66. doi: 10.1016/j.conb.2005.01.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Schmidt H, Rathjen FG. Signalling mechanisms regulating axonal branching in vivo. Bioessays. 2010;32:977–85. doi: 10.1002/bies.201000054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Feldheim DA, O’Leary DD. Visual map development: bidirectional signaling, bifunctional guidance molecules, and competition. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol. 2010;2:a001768. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a001768. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Stanfield BB. The development of the corticospinal projection. Prog Neurobiol. 1992;38:169–202. doi: 10.1016/0301-0082(92)90039-h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.O’Leary DD, Terashima T. Cortical axons branch to multiple subcortical targets by interstitial axon budding: implications for target recognition and “waiting periods”. Neuron. 1988;1:901–10. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(88)90147-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lu SM, Lin RC. Thalamic afferents of the rat barrel cortex: a light- and electron-microscopic study using Phaseolus vulgaris leucoagglutinin as an anterograde tracer. Somatosens Mot Res. 1993;10:1–16. doi: 10.3109/08990229309028819. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fame RM, MacDonald JL, Macklis JD. Development, specification, and diversity of callosal projection neurons. Trends Neurosci. 2011;34:41–50. doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2010.10.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cajal SRy. Histology of the Nervous System of Man and Vertebrates. Oxford University Press; 1895. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dickson BJ. Molecular mechanisms of axon guidance. Science. 2002;298:1959–64. doi: 10.1126/science.1072165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ma L, Tessier-Lavigne M. Dual branch-promoting and branch-repelling actions of Slit/Robo signaling on peripheral and central branches of developing sensory axons. J Neurosci. 2007;27:6843–51. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1479-07.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Schmidt H, et al. The receptor guanylyl cyclase Npr2 is essential for sensory axon bifurcation within the spinal cord. J Cell Biol. 2007;179:331–40. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200707176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.O’Leary DD, et al. Target selection by cortical axons: alternative mechanisms to establish axonal connections in the developing brain. Cold Spring Harb Symp Quant Biol. 1990;55:453–68. doi: 10.1101/sqb.1990.055.01.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bastmeyer M, O’Leary DD. Dynamics of target recognition by interstitial axon branching along developing cortical axons. J Neurosci. 1996;16:1450–9. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.16-04-01450.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kuang RZ, Kalil K. Development of specificity in corticospinal connections by axon collaterals branching selectively into appropriate spinal targets. J Comp Neurol. 1994;344:270–82. doi: 10.1002/cne.903440208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Luo L, O’Leary DD. Axon retraction and degeneration in development and disease. Annu Rev Neurosci. 2005;28:127–56. doi: 10.1146/annurev.neuro.28.061604.135632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Norris CR, Kalil K. Guidance of callosal axons by radial glia in the developing cerebral cortex. J Neurosci. 1991;11:3481–92. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.11-11-03481.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Halloran MC, Kalil K. Dynamic behaviors of growth cones extending in the corpus callosum of living cortical brain slices observed with video microscopy. J Neurosci. 1994;14:2161–77. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.14-04-02161.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Szebenyi G, Callaway JL, Dent EW, Kalil K. Interstitial branches develop from active regions of the axon demarcated by the primary growth cone during pausing behaviors. J Neurosci. 1998;18:7930–40. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.18-19-07930.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Agmon A, Yang LT, O’Dowd DK, Jones EG. Organized growth of thalamocortical axons from the deep tier of terminations into layer IV of developing mouse barrel cortex. J Neurosci. 1993;13:5365–82. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.13-12-05365.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Portera-Cailliau C, Weimer RM, De Paola V, Caroni P, Svoboda K. Diverse modes of axon elaboration in the developing neocortex. PLoS Biol. 2005;3:e272. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0030272. An elegant live cell in vivo imaging study using two-photon time lapse microscopy to follow the postnatal development of thalamocortical and Cajal-Retzius axons and their collaterals in the mouse cortex over time scales from minutes to days during the first three weeks of postnatal development. Although these axons have different morphologies and dynamics, branches of both types of axons develop interstitially and not by growth cone splitting, providing direct evidence that in vivo vertebrate CNS axons primarily form branches interstitially. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yates PA, Roskies AL, McLaughlin T, O’Leary DD. Topographic-specific axon branching controlled by ephrin-As is the critical event in retinotectal map development. J Neurosci. 2001;21:8548–63. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.21-21-08548.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Simon DK, O’Leary DD. Limited topographic specificity in the targeting and branching of mammalian retinal axons. Dev Biol. 1990;137:125–34. doi: 10.1016/0012-1606(90)90013-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.McLaughlin T, O’Leary DD. Molecular gradients and development of retinotopic maps. Annu Rev Neurosci. 2005;28:327–55. doi: 10.1146/annurev.neuro.28.061604.135714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kaethner RJ, Stuermer CA. Dynamics of terminal arbor formation and target approach of retinotectal axons in living zebrafish embryos: a time-lapse study of single axons. J Neurosci. 1992;12:3257–71. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.12-08-03257.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.O’Rourke NA, Cline HT, Fraser SE. Rapid remodeling of retinal arbors in the tectum with and without blockade of synaptic transmission. Neuron. 1994;12:921–34. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(94)90343-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Metin C, Deleglise D, Serafini T, Kennedy TE, Tessier-Lavigne M. A role for netrin-1 in the guidance of cortical efferents. Development. 1997;124:5063–74. doi: 10.1242/dev.124.24.5063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Richards LJ, Koester SE, Tuttle R, O’Leary DD. Directed growth of early cortical axons is influenced by a chemoattractant released from an intermediate target. J Neurosci. 1997;17:2445–58. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.17-07-02445.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Serafini T, et al. Netrin-1 is required for commissural axon guidance in the developing vertebrate nervous system. Cell. 1996;87:1001–14. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81795-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lai Wing Sun K, Correia JP, Kennedy TE. Netrins: versatile extracellular cues with diverse functions. Development. 2011;138:2153–69. doi: 10.1242/dev.044529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Dent EW, Barnes AM, Tang F, Kalil K. Netrin-1 and semaphorin 3A promote or inhibit cortical axon branching, respectively, by reorganization of the cytoskeleton. J Neurosci. 2004;24:3002–12. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4963-03.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lebrand C, et al. Critical role of Ena/VASP proteins for filopodia formation in neurons and in function downstream of netrin-1. Neuron. 2004;42:37–49. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(04)00108-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Tang F, Kalil K. Netrin-1 induces axon branching in developing cortical neurons by frequency-dependent calcium signaling pathways. J Neurosci. 2005;25:6702–15. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0871-05.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Manitt C, Nikolakopoulou AM, Almario DR, Nguyen SA, Cohen-Cory S. Netrin participates in the development of retinotectal synaptic connectivity by modulating axon arborization and synapse formation in the developing brain. J Neurosci. 2009;29:11065–77. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0947-09.2009. An in vivo imaging study of netrin-1 mediated development of retinal axon arbors in the frog optic tectum, showing that netrin induces dynamic axon branching, increasing branch addition and retraction to ultimately increase total branch number. Importantly, comparison between netrin-1 induced retinotectal axon branching in this study and BDNF-induced retinal axon branching from previous work shows that, although both cues increase arbor complexity, they do so through different dynamic strategies. Thus, different molecular cues can use different strategies that lead to a similar end point in shaping terminal arbors. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Palmer A, Klein R. Multiple roles of ephrins in morphogenesis, neuronal networking, and brain function. Genes Dev. 2003;17:1429–50. doi: 10.1101/gad.1093703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wilkinson DG. Multiple roles of EPH receptors and ephrins in neural development. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2001;2:155–64. doi: 10.1038/35058515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Castellani V, Yue Y, Gao PP, Zhou R, Bolz J. Dual action of a ligand for Eph receptor tyrosine kinases on specific populations of axons during the development of cortical circuits. J Neurosci. 1998;18:4663–72. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.18-12-04663.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Mann F, Peuckert C, Dehner F, Zhou R, Bolz J. Ephrins regulate the formation of terminal axonal arbors during the development of thalamocortical projections. Development. 2002;129:3945–55. doi: 10.1242/dev.129.16.3945. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Klein R. Bidirectional modulation of synaptic functions by Eph/ephrin signaling. Nat Neurosci. 2009;12:15–20. doi: 10.1038/nn.2231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Marler KJ, et al. A TrkB/EphrinA interaction controls retinal axon branching and synaptogenesis. J Neurosci. 2008;28:12700–12. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1915-08.2008. In vitro ephrinA5 stripe assays with chick retinal ganglion cell axons revealed a novel interaction between ephrinA5 and the BDNF receptor TRKB on retinal ganglion cell axons. This interaction was shown to promote axon branching by augmenting the PI-3 kinase pathway, leading to a model in which BDNF acts as a global branch promoting factor in the tectum and ephrinAs–EphAs locally suppress this activity resulting in topographically specific retinotectal axon branching. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Mann F, Ray S, Harris W, Holt C. Topographic mapping in dorsoventral axis of the Xenopus retinotectal system depends on signaling through ephrin-B ligands. Neuron. 2002;35:461–73. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(02)00786-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Pasterkamp RJ. Getting neural circuits into shape with semaphorins. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2012;13:605–18. doi: 10.1038/nrn3302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Polleux F, Giger RJ, Ginty DD, Kolodkin AL, Ghosh A. Patterning of cortical efferent projections by semaphorin-neuropilin interactions. Science. 1998;282:1904–6. doi: 10.1126/science.282.5395.1904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Bagnard D, Lohrum M, Uziel D, Puschel AW, Bolz J. Semaphorins act as attractive and repulsive guidance signals during the development of cortical projections. Development. 1998;125:5043–53. doi: 10.1242/dev.125.24.5043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Liu Y, Halloran MC. Central and peripheral axon branches from one neuron are guided differentially by Semaphorin3D and transient axonal glycoprotein-1. J Neurosci. 2005;25:10556–63. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2710-05.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Bagri A, Cheng HJ, Yaron A, Pleasure SJ, Tessier-Lavigne M. Stereotyped pruning of long hippocampal axon branches triggered by retraction inducers of the semaphorin family. Cell. 2003;113:285–99. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(03)00267-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Cioni JM, et al. SEMA3A signaling controls layer-specific interneuron branching in the cerebellum. Curr Biol. 2013;23:850–61. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2013.04.007. Shows in vivo and in vitro that SEMA3A, acting through its neuropilin-1 receptor, induces the branching of basket cell axons onto Purkinje cells in vivo and in vitro. Significantly, localized signalling mechanisms involving the Src kinase FYN in basket cell axons promote layer-specific branching without affecting overall axon organization, demonstrating the importance of localized signalling in specificity of axon branching. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Lopez-Bendito G, et al. Robo1 and Robo2 cooperate to control the guidance of major axonal tracts in the mammalian forebrain. J Neurosci. 2007;27:3395–407. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4605-06.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Wang KH, et al. Biochemical purification of a mammalian slit protein as a positive regulator of sensory axon elongation and branching. Cell. 1999;96:771–84. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80588-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Yeo SY, et al. Involvement of Islet-2 in the Slit signaling for axonal branching and defasciculation of the sensory neurons in embryonic zebrafish. Mech Dev. 2004;121:315–24. doi: 10.1016/j.mod.2004.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Campbell DS, et al. Slit1a inhibits retinal ganglion cell arborization and synaptogenesis via Robo2-dependent and -independent pathways. Neuron. 2007;55:231–45. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2007.06.034. An in vivo time lapse imaging study in the zebrafish retinotectal system showing that SLIT1a inhibits arborization of retinal ganglion cell axons in the zebrafish optic tectum, thereby preventing the premature maturation of terminal arbors. These results contrast with the growth promoting effects of SLITs on peripheral axon arbors, demonstrating that one guidance cue can have different effects on axon branching in different cell types. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Gallo G, Letourneau PC. Localized sources of neurotrophins initiate axon collateral sprouting. J Neurosci. 1998;18:5403–14. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.18-14-05403.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Gallo G, Letourneau PC. Neurotrophins and the dynamic regulation of the neuronal cytoskeleton. J Neurobiol. 2000;44:159–73. doi: 10.1002/1097-4695(200008)44:2<159::aid-neu6>3.0.co;2-h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Gibney J, Zheng JQ. Cytoskeletal dynamics underlying collateral membrane protrusions induced by neurotrophins in cultured Xenopus embryonic neurons. J Neurobiol. 2003;54:393–405. doi: 10.1002/neu.10149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Jeanneteau F, Deinhardt K, Miyoshi G, Bennett AM, Chao MV. The MAP kinase phosphatase MKP-1 regulates BDNF-induced axon branching. Nat Neurosci. 2010;13:1373–9. doi: 10.1038/nn.2655. An important study in identifying novel signalling mechanisms whereby the extracellular cue BDNF induces cortical axon branching in vivo and in vitro. Transient induction of the MAPK phosphatase MKP-1, which inactivates JNK, leads to activation of stathmin and destabilization of microtubules, which facilitates BDNF-induced axon branching. This study therefore links extracellular cues to signalling pathways that influence cytoskeletal reorganization involved in axon branching. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Szebenyi G, et al. Fibroblast growth factor-2 promotes axon branching of cortical neurons by influencing morphology and behavior of the primary growth cone. J Neurosci. 2001;21:3932–41. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.21-11-03932.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Danzer SC, Crooks KR, Lo DC, McNamara JO. Increased expression of brain-derived neurotrophic factor induces formation of basal dendrites and axonal branching in dentate granule cells in hippocampal explant cultures. J Neurosci. 2002;22:9754–63. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-22-09754.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Marshak S, Nikolakopoulou AM, Dirks R, Martens GJ, Cohen-Cory S. Cell-autonomous TrkB signaling in presynaptic retinal ganglion cells mediates axon arbor growth and synapse maturation during the establishment of retinotectal synaptic connectivity. J Neurosci. 2007;27:2444–56. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4434-06.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Cohen-Cory S, Kidane AH, Shirkey NJ, Marshak S. Brain-derived neurotrophic factor and the development of structural neuronal connectivity. Dev Neurobiol. 2010;70:271–88. doi: 10.1002/dneu.20774. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Alsina B, Vu T, Cohen-Cory S. Visualizing synapse formation in arborizing optic axons in vivo: dynamics and modulation by BDNF. Nat Neurosci. 2001;4:1093–101. doi: 10.1038/nn735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Ciani L, Salinas PC. WNTs in the vertebrate nervous system: from patterning to neuronal connectivity. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2005;6:351–62. doi: 10.1038/nrn1665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Salinas PC. Modulation of the microtubule cytoskeleton: a role for a divergent canonical Wnt pathway. Trends Cell Biol. 2007;17:333–42. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2007.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Hall AC, Lucas FR, Salinas PC. Axonal remodeling and synaptic differentiation in the cerebellum is regulated by WNT-7a signaling. Cell. 2000;100:525–35. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80689-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Krylova O, et al. WNT-3, expressed by motoneurons, regulates terminal arborization of neurotrophin-3-responsive spinal sensory neurons. Neuron. 2002;35:1043–56. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(02)00860-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Purro SA, et al. Wnt regulates axon behavior through changes in microtubule growth directionality: a new role for adenomatous polyposis coli. J Neurosci. 2008;28:8644–54. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2320-08.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Keeble TR, et al. The Wnt receptor Ryk is required for Wnt5a-mediated axon guidance on the contralateral side of the corpus callosum. J Neurosci. 2006;26:5840–8. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1175-06.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Liu Y, et al. Ryk-mediated Wnt repulsion regulates posterior-directed growth of corticospinal tract. Nat Neurosci. 2005;8:1151–9. doi: 10.1038/nn1520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Zou Y, Lyuksyutova AI. Morphogens as conserved axon guidance cues. Curr Opin Neurobiol. 2007;17:22–8. doi: 10.1016/j.conb.2007.01.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Hutchins BI, Li L, Kalil K. Wnt/calcium signaling mediates axon growth and guidance in the developing corpus callosum. Dev Neurobiol. 2011;71:269–83. doi: 10.1002/dneu.20846. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Li L, Hutchins BI, Kalil K. Wnt5a induces simultaneous cortical axon outgrowth and repulsive axon guidance through distinct signaling mechanisms. J Neurosci. 2009;29:5873–83. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0183-09.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Bodmer D, Levine-Wilkinson S, Richmond A, Hirsh S, Kuruvilla R. Wnt5a mediates nerve growth factor-dependent axonal branching and growth in developing sympathetic neurons. J Neurosci. 2009;29:7569–81. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1445-09.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Dent EW, Gertler FB. Cytoskeletal dynamics and transport in growth cone motility and axon guidance. Neuron. 2003;40:209–27. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(03)00633-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Kalil K, Szebenyi G, Dent EW. Common mechanisms underlying growth cone guidance and axon branching. J Neurobiol. 2000;44:145–58. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Dent EW, Gupton SL, Gertler FB. The growth cone cytoskeleton in axon outgrowth and guidance. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol. 2011;3 doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a001800. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Lowery LA, Van Vactor D. The trip of the tip: understanding the growth cone machinery. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2009;10:332–43. doi: 10.1038/nrm2679. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Vitriol EA, Zheng JQ. Growth cone travel in space and time: the cellular ensemble of cytoskeleton, adhesion, and membrane. Neuron. 2012;73:1068–81. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2012.03.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Dent EW, Kalil K. Axon branching requires interactions between dynamic microtubules and actin filaments. J Neurosci. 2001;21:9757–69. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.21-24-09757.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Ketschek A, Gallo G. Nerve growth factor induces axonal filopodia through localized microdomains of phosphoinositide 3-kinase activity that drive the formation of cytoskeletal precursors to filopodia. J Neurosci. 2010;30:12185–97. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1740-10.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Spillane M, et al. Nerve growth factor-induced formation of axonal filopodia and collateral branches involves the intra-axonal synthesis of regulators of the actin-nucleating Arp2/3 complex. J Neurosci. 2012;32:17671–89. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1079-12.2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Spillane M, et al. The actin nucleating Arp2/3 complex contributes to the formation of axonal filopodia and branches through the regulation of actin patch precursors to filopodia. Dev Neurobiol. 2011;71:747–58. doi: 10.1002/dneu.20907. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Medeiros NA, Burnette DT, Forscher P. Myosin II functions in actin-bundle turnover in neuronal growth cones. Nat Cell Biol. 2006;8:215–26. doi: 10.1038/ncb1367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Bear JE, Gertler FB. Ena/VASP: towards resolving a pointed controversy at the barbed end. J Cell Sci. 2009;122:1947–53. doi: 10.1242/jcs.038125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Dwivedy A, Gertler FB, Miller J, Holt CE, Lebrand C. Ena/VASP function in retinal axons is required for terminal arborization but not pathway navigation. Development. 2007;134:2137–46. doi: 10.1242/dev.002345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Dent EW, et al. Filopodia are required for cortical neurite initiation. Nat Cell Biol. 2007;9:1347–59. doi: 10.1038/ncb1654. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Ahuja R, et al. Cordon-bleu is an actin nucleation factor and controls neuronal morphology. Cell. 2007;131:337–50. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.08.030. This paper identifies a novel actin nucleator, cordon-bleu, which gives rise to long non-bundled unbranched filaments that elongate by barbed-end growth; this contrasts with ARP2/3, which gives rise to branched filaments. When overexpressed in hippocampal neurons in vitro, cordon-bleu increases axon branching without affecting axon length, but interestingly, it also increases the number of dendrites and their branching. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Korobova F, Svitkina T. Arp2/3 complex is important for filopodia formation, growth cone motility, and neuritogenesis in neuronal cells. Mol Biol Cell. 2008;19:1561–74. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E07-09-0964. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Strasser GA, Rahim NA, VanderWaal KE, Gertler FB, Lanier LM. Arp2/3 is a negative regulator of growth cone translocation. Neuron. 2004;43:81–94. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2004.05.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Lu M, Witke W, Kwiatkowski DJ, Kosik KS. Delayed retraction of filopodia in gelsolin null mice. J Cell Biol. 1997;138:1279–87. doi: 10.1083/jcb.138.6.1279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Chen TJ, Gehler S, Shaw AE, Bamburg JR, Letourneau PC. Cdc42 participates in the regulation of ADF/cofilin and retinal growth cone filopodia by brain derived neurotrophic factor. J Neurobiol. 2006;66:103–14. doi: 10.1002/neu.20204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Dent EW, Callaway JL, Szebenyi G, Baas PW, Kalil K. Reorganization and movement of microtubules in axonal growth cones and developing interstitial branches. J Neurosci. 1999;19:8894–908. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.19-20-08894.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Conde C, Caceres A. Microtubule assembly, organization and dynamics in axons and dendrites. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2009;10:319–32. doi: 10.1038/nrn2631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Mitchison T, Kirschner M. Cytoskeletal dynamics and nerve growth. Neuron. 1988;1:761–72. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(88)90124-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Gallo G, Letourneau PC. Different contributions of microtubule dynamics and transport to the growth of axons and collateral sprouts. J Neurosci. 1999;19:3860–73. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.19-10-03860.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Yu W, Ahmad FJ, Baas PW. Microtubule fragmentation and partitioning in the axon during collateral branch formation. J Neurosci. 1994;14:5872–84. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.14-10-05872.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Yu W, et al. The microtubule-severing proteins spastin and katanin participate differently in the formation of axonal branches. Mol Biol Cell. 2008;19:1485–98. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E07-09-0878. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Qiang L, Yu W, Andreadis A, Luo M, Baas PW. Tau protects microtubules in the axon from severing by katanin. J Neurosci. 2006;26:3120–9. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5392-05.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Zhou FQ, Zhou J, Dedhar S, Wu YH, Snider WD. NGF-induced axon growth is mediated by localized inactivation of GSK-3beta and functions of the microtubule plus end binding protein APC. Neuron. 2004;42:897–912. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2004.05.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Yokota Y, et al. The adenomatous polyposis coli protein is an essential regulator of radial glial polarity and construction of the cerebral cortex. Neuron. 2009;61:42–56. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2008.10.053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Chen Y, Tian X, Kim WY, Snider WD. Adenomatous polyposis coli regulates axon arborization and cytoskeleton organization via its N-terminus. PLoS One. 2011;6:e24335. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0024335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]