Randomized controlled trials represent the gold standard for comparative effective research, but additional methods are available when randomized controlled trials are lacking or inconclusive. Comparative effective research requires oversight of study design and analysis, but if appropriately conducted, offers an opportunity to identify the most effective and safe approach to patient care. Oncologists and oncology societies are uniquely positioned to provide the expertise to steer the appropriate application of comparative effective research.

Keywords: Comparative effectiveness, Outcomes, Clinical trials, Cost-effectiveness, Health policy

Learning Objectives

Describe methods for assessing comparative effectiveness in the absence of data from high-quality randomized, controlled trials.

Outline the criteria that should be applied to systematic reviews in order to use them for comparative effectiveness research.

Abstract

Although randomized controlled trials represent the gold standard for comparative effective research (CER), a number of additional methods are available when randomized controlled trials are lacking or inconclusive because of the limitations of such trials. In addition to more relevant, efficient, and generalizable trials, there is a need for additional approaches utilizing rigorous methodology while fully recognizing their inherent limitations. CER is an important construct for defining and summarizing evidence on effectiveness and safety and comparing the value of competing strategies so that patients, providers, and policymakers can be offered appropriate recommendations for optimal patient care. Nevertheless, methodological as well as political and social challenges for CER remain. CER requires constant and sophisticated methodological oversight of study design and analysis similar to that required for randomized trials to reduce the potential for bias. At the same time, if appropriately conducted, CER offers an opportunity to identify the most effective and safe approach to patient care. Despite rising and unsustainable increases in health care costs, an even greater challenge to the implementation of CER arises from the social and political environment questioning the very motives and goals of CER. Oncologists and oncology professional societies are uniquely positioned to provide informed clinical and methodological expertise to steer the appropriate application of CER toward critical discussions related to health care costs, cost-effectiveness, and the comparative value of the available options for appropriate care of patients with cancer.

Implications for Practice:

Escalating health care costs, largely driven by expensive new technologies and therapies, have prompted calls for more rigorous assessment of the effectiveness, safety, and overall value. At the same time, the time and resources required for large randomized controlled trials, as well as their recognized limitations, necessitate consideration of other forms of comparative effectiveness research for evaluating meaningful clinical outcomes. Through the results derived from selective and appropriate use of a range of comparative effectiveness methodological tools, clinicians, patients, payers, and policy makers can make more rationale choices in selecting the most appropriate, efficient, and cost-effective cancer care. At the same time, practicing oncologists and other stakeholders must be aware of the challenges presented by such research approaches as well as the considerable progress that has been made in addressing these limitations in order to appropriately weigh the totality evidence on critical health care issues in every day oncology practice.

Introduction

Comparative effectiveness research (CER) attempts to compare the benefits and harms of alternative strategies for diagnosing, treating, or preventing disease in patients. Driven primarily by new therapies and technologies, health care expenditures continue to rise, most notably in the U.S. where they have increased more rapidly over the past three decades than in other major industrialized countries (Fig. 1). The aging of the population, increasing cancer incidence rates, greater intensity of cancer care, and the need for continuing care of the growing number of cancer survivors, along with the continuing increase in overall health care costs, all point to a growing economic burden associated with cancer and cancer treatment [1].

Figure 1.

Plot of total annual health care expenditure per capita between 1960 and 2010 for selected major economies based on data reported to The Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) (http://www.oecd.org/). Expenditures are reported in U.S. dollars based on purchasing power parity estimates as of August 10, 2012. Annual estimates for the U.S. are highlighted in red, and the average for other OECD countries highlighted in green.

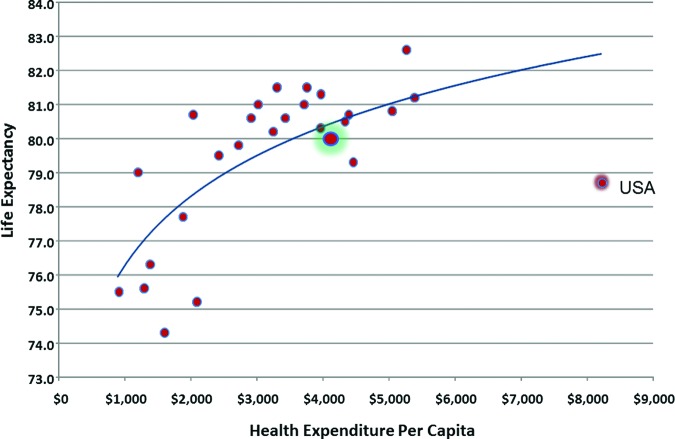

Despite rapidly rising health care costs, there has been limited or no improvement in major measures of health in the U.S. (Fig. 2) [2]. Americans experience some of the highest infant mortality rates and shortest life expectancies among industrialized nations [3]. At the same time, the relentless influx of novel and costly agents and technologies fueled by a better understanding of the molecular and genomic underpinnings of disease further challenges the future of health care delivery in the U.S. Current funding for health care and clinical trials in the U.S. is unsustainable and begs for the development of reliable measures for identifying, comparing, and selecting optimal diagnostic and therapeutic strategies providing the greatest value. To address this challenging environment, CER strives to define the optimal strategies for delivering the most effective and safe interventions to appropriate populations in the most efficient way. While often confused with restrictions, rationing, and cost containment, when appropriately guided from an objective scientific and clinical perspective, including appropriate outcomes of interest and clinically relevant measures of efficacy, safety, or overall value, CER strives to differentiate what works from what does not [4]. The ultimate goal is to assist patients, providers, and policymakers in making rational evidence-based choices to improve the health of individuals and society as a whole.

Figure 2.

Plot of estimated life expectancy at birth by total health care expenditure per capita for 2010 for selected major economies reporting to OECD (http://www.oecd.org/). Expenditures are reported in U.S. dollars based on purchasing power parity estimates as of August 10, 2012. Estimates for the U.S. are highlighted in red, and estimates for other OECD countries are highlighted in green.

Comparative Effectiveness Research Methods

Randomized Controlled Trials

Randomized controlled trials (RCTs) and meta-analyses of RCTs continue to represent the gold standard for CER (Table 1) [5]. However, generalizable data from multiple large, well-designed RCTs are often not available on major clinical questions in oncology. In oncology, as in any field, there may be questions that do not need to be or should not be tested in an RCT to assess their value [6]. At the same time, a number of important limitations to existing RCTs are recognized, including high costs, time to completion, narrow eligibility criteria, and limited attention to treatment-related toxicities and quality of life. As a result, they may not adequately address effectiveness and safety in the broader cancer population, and safety issues may not emerge until years later. CER is not a license to do away with RCTs but rather represents an opportunity to complement and go beyond RCTs into areas not otherwise addressed.

Table 1.

Types of comparative effectiveness research

… a number of important limitations to existing RCTs are recognized, including high costs, time to completion, narrow eligibility criteria, and limited attention to treatment-related toxicities and quality of life. As a result, they may not adequately address effectiveness and safety in the broader cancer population, and safety issues may not emerge until years later. CER is not a license to do away with RCTs but rather represents an opportunity to complement and go beyond RCTs into areas not otherwise addressed.

Before abandoning RCTs because of their limitations, consideration should be given to making them more relevant, generalizable, and rapid in development and implementation, while reducing their complexity and sample size requirements, all of which may lower costs [7]. Nevertheless, alternative sources of evidence are needed to guide the evaluation and approval of new interventions while addressing the need to make critical clinical and public health decisions. When properly applied, such approaches may provide reasonable, valid, and more generalizable estimates of comparative effectiveness, safety, and cost and may also generate hypotheses that form the basis of future confirmatory RCTs [4, 7].

Observational Studies

Observational studies based on data not specifically designed for comparative studies such as cohort studies, registries, and administrative databases serve as an important source of information on patients, disease characteristics, treatment information, comorbidities, and treatment-related toxicities, as well as health system information and health care costs. However, when the intervention of interest is not randomly assigned but at the discretion of the treating clinician, the choice of intervention may be influenced by multiple potential confounding factors, which also impact outcomes potentially obscuring or creating an apparent treatment effect. While such studies should be comparative, they can be biased by inappropriate selection of patients in the experimental cohort as well as in the control group [7].

Although electronic health records have enhanced the capture and immediate access to clinical data, there are many examples for which the results of observational studies has led to long-held beliefs that were subsequently refuted in RCTs [8–13]. Such studies may be limited by inaccurately recorded clinical measures and a large number of missing variables. Important data related to drugs, doses, schedule, delays, modifications, and adverse events are often lacking, and it is virtually impossible to capture the reasons that certain patients are treated in a particular fashion. One cannot adjust for potential confounding due to unknown, unmeasured, or ignored variables, and efforts to do so, such as the use of instrumental variables and propensity score analysis, have their own important limitations [10].

Statistical oversight of observational studies is important because the methodological challenges can be every bit as challenging or more so as with RCTs. The same rigorous attention to study design, conduct, analysis, and reporting should be applied to observational studies as to high-quality RCTs. However, most observational studies are exploratory in nature with no predefined hypothesis or biological rationale and, therefore, a low a priori probability of being true [14]. As with RCTs, subgroup analyses should only be taken seriously when considered a priori based on reasonable hypotheses or confirmed independently [10]. The temptation to conduct multiple hypothesis tests often leads to false positive results and inappropriate conclusions. Although observational studies and RCTs often agree, it has been estimated that upward of one fourth report significantly different results [15].

Nevertheless, with careful attention to the potential for both random and systematic error, observational data can enhance CER in a more real-world setting. Considerable progress has been made in defining objective and reliable standards for observational research. The Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) recommendations for observational studies offers a checklist for reporting the results of such studies [16]. In addition, the Good Research for Comparative Effectiveness (GRACE) principles provide recommendations for designing and evaluating comparative effectiveness observational studies [17]. Recommendations for the analysis of observational studies are offered by the International Society of Pharmacoeconomics and Outcomes Research in the European Network of Centres for Pharmacoepidemiology and Pharmacovigilance (ENCePP) methodological standards [18]. Thomas and Peterson have encouraged the use of prospectively defined statistical analysis plans for observational research similar to those routinely provided with RCTs, including specification of the population, endpoints, objectives, hypotheses, and statistical methods (such as the handling of missing data and methods for addressing potential confounding and interaction) [19]. Finally, editorial guidance from medical journal editors has been provided, including principles and standards for the conduct and reporting of CER [20].

Rapid Learning Health Systems

Considerable enthusiasm has emerged for the development of rapid learning health systems since the release of an Institute of Medicine (IOM) report in 2007 entitled “The Learning Healthcare System” [21]. It is proposed that health information systems that are more synchronized and adaptable to the pace of increasing evidence will enable real-time implementation of clinical decision support systems, improve the quality of patient care, and enhance clinical research efforts including data mining. Such systems will be dependent on widespread adoption of electronic health records and standardization of terminology related to clinical and laboratory measures across platforms and resolution of issues around data governance and patient confidentiality [22–24]. Nevertheless, data emerging from such systems are observational in nature with many of the same limitations, including missing values and confounding by factors related to both treatment selection and clinical outcome. The analytic methods available are essentially the same that have been used to analyze observational data for decades with the same impediments. Therefore, drawing inferences from such data to make recommendations for clinical decision making is fraught with challenges. Although clinical decision support systems have demonstrated the ability to improve health care process measures, evidence that they improve clinical, economic, or efficiency outcomes is limited [25]. We must avoid the temptation to assume that observational data gathered electronically in great quantities and processed rapidly are necessarily better or more reliable [26].

Systematic Reviews

Systematic reviews and evidence summaries including meta-analyses can be useful when small individual trials of similar design are not in themselves definitive. However, the trials included must be strictly comparable in terms of patients, endpoints, and follow up so as to avoid interpreting trial to trial differences not caused by the intervention as a treatment effect [7]. Systematic reviews should define a rigorous process of search, review, selection, data abstraction, and analysis a priori, including assessment of heterogeneity and study quality [27]. A recent report from the IOM Committee on Standards for Systematic Reviews of CER entitled “Finding What Works in Health Care: Standards for Systematic Reviews” proposed methodological standards to assure objective, transparent, and scientifically valid systematic reviews focusing on therapeutic interventions [28]. The IOM report recommends explicit objective standards for initiating a systematic review, finding and assessing individual studies, synthesizing the evidence, and reporting. Major medical journals now encourage or require compliance with the Preferred Reporting Items for the Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) statement for conducting and reporting meta-analyses representing an enhancement of the original Quality of Reporting of Meta-analysis (QUOROM) statement [29–31]. Similar recommendations for Meta-analysis of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (MOOSE) have been put forward [32].

Clinical Practice Guidelines

One of the primary purposes of systematic reviews is to inform clinical practice guidelines (CPGs) [27]. The development of recommendations in CPGs is not inherent to CER but may result from the review and interpretation of CER results. The integration of CER based on systematic reviews and CPGs was addressed by a companion IOM document entitled “Clinical Practice Guidelines We Can Trust” [33]. Evidence-based CPGs provide recommendations informed by systematic reviews of the evidence and an assessment of benefits and harms. CPGs should be explicit and transparent, manage conflict of interest, utilize disease and methodology experts as well as patient representatives, rate the quality of evidence and strength of the recommendations, submit for external review, and be updated when important new evidence is identified [33]. The development of CPGs requires adherence to formal, rigorous methods intended to minimize bias and potential conflict of interest [27, 33].

Clinical Decision Modeling

Decision making in oncology is increasingly complex with continuously expanding treatment options with varying effectiveness and toxicity as well as costs, made even more complicated by available molecular prognostic and predictive factors and the compelling need to account for patient preferences and costs on the individual and society. A variety of modeling methods are available for simulating important clinical decisions and integrating benefits, harms, and costs in terms of cost-effectiveness, cost-utility, or overall value. Such modeling has been applied to a wide range of conventional as well as novel interventions in oncology (Table 2) [34]. Clinical simulation models attempt to emulate realistic clinical scenarios utilizing the totality of available evidence along with the experience of expert clinicians. Properly conducted, such models can address relevant clinical questions accounting for measurement variability permitting reasonable estimates of the comparative effectiveness, safety, and cost or the overall value of an intervention.

Table 2.

Cost per quality-adjusted life-year (QALY) gained for selected clinical strategiesa

Values are given in 2008 U.S. dollars, with adjustments for inflation according to the Consumer Price Index. Numbers are the ratios of the added cost per person to the gain in QALYs per person (Weinstein and Skinner [34]).

However, in addition to defining appropriate clinical scenarios, modeling studies require numerous assumptions concerning the probability of events and various clinical outcomes, utilities, and costs. These assumptions can be varied in sensitivity analyses to study their influence on the best decision and outcomes. Challenges remain, however, about investigator conflict of interest and how to appropriately weigh improved outcomes such as survival against unnecessary interventions, complications, impaired quality of life, and costs. Treatment-related toxicities and patient reported outcomes (PROs), often considered secondary outcomes, are inconsistently reported, have frequent missing values, and demonstrate large variation with little consensus about what represents meaningful clinical differences. Similarly, adjustments must be made for costs captured over extended periods of time or in different geographic regions. Nevertheless, when appropriately conducted, clinically relevant risk prediction and clinical decision models can complement and extend our understanding beyond what trials have been able to tell us. Better methods have been developed to assess the clinical value of risk-prediction tools and decision models [35]. Clinical decision and relative utility curves incorporate the harms and benefits and estimate the net benefit across possible risk thresholds to provide a more complete evaluation of comparative strategies [36–38].

Personalized and Genomic Medicine

One of the greatest challenges as well as opportunities for CER pertains to efforts to provide more personalized care to patients based on clinical, molecular, and genomic markers associated with treatment response, resistance, or safety (Table 3) [39, 40]. Targeted interventions have the potential to increase effectiveness while reducing complications by identifying patients most likely to benefit. More selective use of expensive technologies may also reduce health care expenditures or increase the value of cancer treatment. Unfortunately, the quality of research published to date has varied considerably and has not clearly demonstrated the clinical utility of many such interventions [26]. As reported in a recent systematic review of reported validation studies of multigene array signatures for predicting chemotherapy response, the quality of study design, analysis, and reporting in the medical literature is severely lacking [41].

Table 3.

Comparative effectiveness research

aConsolidated standards of reporting trials including patient-reported outcomes [55].

bStrengthening the reporting of observational studies in epidemiology.

cGood research for comparative effectiveness.

dEuropean Network of Centres for Pharmacoepidemiology and Pharmacovigilance Methodologic Standards.

eSee [20].

fLearning Healthcare Systems.

gFinding what works in health care: Standards for systematic reviews.

hQuality of reporting of meta-analysis.

iPreferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses.

jMeta-analysis of observational studies in epidemiology.

kClinical practice guidelines we can trust.

lEstimate net benefits and harms across all thresholds.

mEvoluation of translational omics: Lessons learned and the path forward.

nEvaluation of clinical validity and clinical utility of actionable molecular diagnostic tests in adult oncology.

Abbreviation: CDS, clinical decision support.

A recent IOM report entitled “Evolution of Translational Omics: Lessons Learned and the Path Forward” notes that the translation of these new technologies into validated clinical tests to improve patient care has happened more slowly than anticipated [42]. Multiple organizations, including the IOM, the Center for Medical Technology Policy, and the National Comprehensive Cancer Network, among others, have issued guidance for the conduct of research into molecular and genomic diagnostics, prognostics, and therapy [42–46]. Initial discovery work needs to be accompanied by assessment of analytic validity, including plausibility and test performance, under conditions in which the assay results are blinded to study outcomes. Clinical validity should then be assessed in an independent adequately powered cohort with adjustment for known prognostic or predictive factors and assessment of any drug–biomarker interaction. The clinical utility of the assay in altering clinical decision making or improving the balance of benefit and harm compared with standard care then should be evaluated, along with efforts to achieve consensus among stakeholders concerning the overall value of an assay [47]. Remaining challenges include the rapid pace of innovation, lack of regulation, variable definitions, and the thresholds utilized for clinical application [48]. First and foremost, genomic assays need to be reproducible and fully assessed for scientific validity before they are used to guide patient treatment in clinical trials [42]. Nowhere in modern clinical research is the need for early and continuous statistical oversight more imperative, but all too often lacking. Nevertheless, CER methods offer a major opportunity for the effective translation of genomic discoveries into effective, safe, and cost-effective clinical strategies.

Real World Experience with CER

Several other industrialized countries have embraced CER as a basis for more rational health policies and guiding therapeutic options and choices. Earle and colleagues have discussed the role of CER in formulating cancer funding decisions for patient care and research as well as other health policies in Ontario, Canada [49]. The authors point out that CER is playing an increasing role in addressing multiple challenges to Ontario's universal health care system, including the funding of drugs. They utilize the example of trastuzumab, which was recommended in guidelines developed by Ontario's Program in Evidence-Based Care in 1999 for use in patients with HER2-positive metastatic breast cancer based on an overall survival improvement in RCTs. This was then followed by recommendations for use in the adjuvant and neoadjuvant setting when high-level evidence became available in 2005. Once efficacy has been sufficiently demonstrated, the economic impact of a new agent is evaluated by the Committee to Evaluate Drugs based on available economic models or evidence developed by the Pharmacoeconomics Research Unit of Cancer Care Ontario (CCO). A final recommendation based on the clinical efficacy and economic evidence is made to the provincial government, which usually but not always accepts the recommendation. Trastuzumab was approved for appropriate use in these settings based on this review process described. Given the lack of efficacy data in tumors <1 cm in size, a recently created evidence building program (EBP) was created to develop and collect real-world data on cancer agents outside of approved reimbursement criteria during a period of conditional approval. Similarly, Sorenson and colleagues have recently summarized their experience at the National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE) in the United Kingdom [50]. With a more restrictive methodology with greater emphasis on costs, approval of trastuzumab for women with early-stage HER2-positive breast cancer was delayed and created considerable controversy. Although such a restrictive strategy for cancer drug approval is unlikely in the U.S., the adoption of some form of value-based reimbursement would appear to be inevitable given the current rising and unsustainable cost of cancer care [51].

Social and Political Challenges

Ultimately, the greatest challenge to CER in oncology is not methodological but sociopolitical, relating to issues associated with costs, the need for health care reform, and the integration of CER and value into the public discourse [3, 52]. Despite the successes and strengths of the U.S. health care system, it is the most expensive in the world, providing inequitable and inefficient care for many and leaving 20% of the nonelderly population uninsured. Americans remain divided over the Affordable Care Act (ACA), and political forces continue efforts to reverse the law, including provisions to implement CER into health care policy and planning. It is important to note that CER, as envisioned under the ACA, is not a policy process but a method for generating and validating evidence through RCTs, registries, and other data sources to better inform health care decisions [1, 53]. Even with the implementation of health care reform, challenges will persist when individual expectations for care exceed those considered of sufficient value to payers or health systems. CER has the opportunity to bring the data and discussion to a level of clarity and transparency for more rational and balanced choices in both regulatory and reimbursement decisions by providing a formal process for evaluating the totality of evidence on the effectiveness, safety, and value of available interventions. Hopefully, this will lead to greater reliance on scientific evidence in clinical practice and health care policy and coverage [54]. We should examine comparable national health care coverage systems in other developed countries and learn from both their successes and their failures in an effort to develop a high-quality and yet affordable and sustainable health care system that provides reasonable and compassionate coverage for all of our citizens.

Ultimately, the greatest challenge to CER in oncology is not methodological but sociopolitical, relating to issues associated with costs, the need for health care reform, and the integration of CER and value into the public discourse.

Conclusions

CER is not a shortcut for avoiding the considerable effort and cost of large, well-designed RCTs, which remain the gold standard of comparative effectiveness. Nevertheless, in the absence of data or with conflicting results from high-quality RCTs or when such trials are deemed unethical or not feasible, there are a number of research tools available to consider in evaluating comparative effectiveness. Similarly, CER should not represent an avenue to bypass RCTs to achieve some desired policy objective or for restricting reimbursement for effective but costly treatments. Rather, CER is an important construct for identifying and systematically summarizing all available evidence on the effectiveness and safety as well as overall value of alternative strategies.

Nonetheless, challenges remain from within and without. In addition to the need for rigorous and continuous methodological oversight, CER must fully recognize the importance of addressing key clinical questions utilizing relevant study designs followed by appropriate clinical interpretation of the results. The potential for bias is always present necessitating continuous methodolgical oversight as great or greater than that provided for RCTs. Perhaps an even greater challenge to CER comes from a contentious, often politicized debate about the value of CER despite unsustainable increases in health care costs, while health care access remains a challenge for many Americans and measures of health care quality continue to lag. A variety of methodologies applied in a statistically valid and clinically relevant manner need to be explored with the goal of identifying the clinical strategies with the greatest comparative value (Table 3). At the same time, we must raise the level of social and political discourse concerning unsustainable increases in health care costs and the need to identify and apply approaches to medical care associated with the greatest value to both individuals and society. Oncologists can provide the needed clinical and research expertise to properly inform the CER process and guide its integration into national health care discussions and policy formulation. Health care providers and researchers not only need to be at the table on such important health care research and delivery issues, but should be leading the discussion around health care costs, cost-effectiveness, and the comparative value of cancer care options.

This article is available for continuing medical education credit at CME.TheOncologist.com.

Acknowledgments

Dr. Lyman is supported by grants from the National Cancer Institute (RC2CA148041–01) and the National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute (1R01HL095109–01).

Footnotes

Editor's Note: See the accompanying commentary on pages 655–657.

Disclosures

The author indicated no financial relationships.

Editor-in-Chief: Bruce Chabner: Sanofi, Epizyme, PharmaMar, GlaxoSmithKline, Pharmacyclics, Pfizer, Ariad (C/A); Eli Lilly (H); Gilead, Epizyme, Celgene, Exelixis (O)

Reviewer “A”: None

(C/A) Consulting/advisory relationship; (RF) Research funding; (E) Employment; (H) Honoraria received; (OI) Ownership interests; (IP) Intellectual property rights/inventor/patent holder; (SAB) Scientific advisory board

Reference

- 1.Yabroff KR, Lund J, Kepka D, et al. Economic burden of cancer in the United States: Estimates, projections, and future research. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2011;20:2006–2014. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-11-0650. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Davis K. Slowing the growth of health care costs—learning from international experience. N Engl J Med. 2008;359:1751–1755. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp0805261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Oberlander J. Unfinished journey—a century of health care reform in the United States. N Engl J Med. 2012;367:585–590. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1202111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lyman GH. Comparative effectiveness research in oncology: The need for clarity, transparency and vision. Cancer Invest. 2009;27:593–597. doi: 10.1080/07357900903109952. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Goodman SN. Quasi-random reflections on randomized controlled trials and comparative effectiveness research. Clin Trials. 2012;9:22–26. doi: 10.1177/1740774511433285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Smith GC, Pell JP. Parachute use to prevent death and major trauma related to gravitational challenge: Systematic review of randomised controlled trials. BMJ. 2003;327:1459–1461. doi: 10.1136/bmj.327.7429.1459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Korn EL, Freidlin B. Methodology for comparative effectiveness research: Potential and limitations. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30:4185–4187. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2012.44.8233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Benson K, Hartz AJ. A comparison of observational studies and randomized, controlled trials. N Engl J Med. 2000;342:1878–1886. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200006223422506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Concato J, Shah N, Horwitz RI. Randomized, controlled trials, observational studies, and the hierarchy of research designs. N Engl J Med. 2000;342:1887–1892. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200006223422507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.DeMets DL, Califf RM. Lessons learned from recent cardiovascular clinical trials: Part I. Circulation. 2002;106:746–751. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.0000023219.51483.66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hurwitz HI, Lyman GH. Registries and randomized trials in assessing the effects of bevacizumab in colorectal cancer: Is there a common theme? J Clin Oncol. 2012;30:580–581. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2011.40.7031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ioannidis JP, Haidich AB, Pappa M, et al. Comparison of evidence of treatment effects in randomized and nonrandomized studies. JAMA. 2001;286:821–830. doi: 10.1001/jama.286.7.821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pritchard KI. Should observational studies be a thing of the past? J Natl Cancer Inst. 2008;100:451–452. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djn074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ioannidis JP. Why most published research findings are false. PLoS Med. 2005;2:e124. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0020124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Shikata S, Nakayama T, Noguchi Y, et al. Comparison of effects in randomized controlled trials with observational studies in digestive surgery. Ann Surg. 2006;244:668–676. doi: 10.1097/01.sla.0000225356.04304.bc. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.von Elm E, Altman DG, Egger M, et al. Strengthening the reporting of observational studies in epidemiology (STROBE) statement: Guidelines for reporting observational studies. BMJ. 2007;335:806–808. doi: 10.1136/bmj.39335.541782.AD. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dreyer NA, Schneeweiss S, McNeil BJ, et al. Grace principles: Recognizing high-quality observational studies of comparative effectiveness. Am J Manag Care. 2010;16:467–471. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Berger ML, Mamdani M, Atkins D, et al. Good research practices for comparative effectiveness research: Defining, reporting and interpreting nonrandomized studies of treatment effects using secondary data sources: The ISPOR good research practices for retrospective database analysis task force report—part I. Value Health. 2009;12:1044–1052. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-4733.2009.00600.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Thomas L, Peterson ED. The value of statistical analysis plans in observational research: Defining high-quality research from the start. J Am Med Assoc. 2012;308:773–774. doi: 10.1001/jama.2012.9502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sox HC, Greenfield S. Comparative effectiveness research: A report from the institute of medicine. Ann Intern Med. 2009;151:203–205. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-151-3-200908040-00125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Olsen L, Aisner D, McGinnis M. The Learning Healthcare System. Washington, D.C.: The National Academies Press; 2007. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Abernethy AP, Ahmad A, Zafar SY, et al. Electronic patient-reported data capture as a foundation of rapid learning cancer care. Med Care. 2010;48:S32–S38. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0b013e3181db53a4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Abernethy AP, Etheredge LM, Ganz PA, et al. Rapid-learning system for cancer care. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28:4268–4274. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2010.28.5478. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ginsburg GS, Staples J, Abernethy AP. Academic medical centers: Ripe for rapid-learning personalized health care. Sci Transl Med. 2011;3:101–127. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3002386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bright TJ, Wong A, Dhurjati R, et al. Effect of clinical decision-support systems: A systematic review. Ann Intern Med. 2012;157:29–43. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-157-1-201207030-00450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Browman GP. Special series on comparative effectiveness research: Challenges to real-world solutions to quality improvement in personalized medicine. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30:4188–4191. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2012.44.8225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Somerfield MR, Einhaus K, Hagerty KL, et al. American society of clinical oncology clinical practice guidelines: Opportunities and challenges. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26:4022–4026. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.17.7139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Eden J, Levit L, Berg A, et al. Washington, D.C.: The National Academies Press; 2011. Finding What Works in Health Care: Standards for Systematic Reviews. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Liberati A, Altman DG, Tetzlaff J, et al. The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate health care interventions: Explanation and elaboration. Ann Intern Med. 2009;151:W65–W94. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-151-4-200908180-00136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, et al. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: The PRISMA statement. Ann Intern Med. 2009;151:264–269. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-151-4-200908180-00135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Moher D, Cook DJ, Eastwood S, et al. Improving the quality of reports of meta-analyses of randomised controlled trials: The QUOROM statement. Quality of reporting of meta-analyses. Lancet. 1999;354:1896–1900. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(99)04149-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Stroup DF, Berlin JA, Morton SC, et al. Meta-analysis of observational studies in epidemiology: A proposal for reporting. Meta-analysis of observational studies in epidemiology (MOOSE) group. JAMA. 2000;283:2008–2012. doi: 10.1001/jama.283.15.2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Graham R, Mancher M, Wolman DM, et al. Washington, D.C.: The National Academies Press; 2011. Clinical Practice Guidelines We Can Trust. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Weinstein MC, Skinner JA. Comparative effectiveness and health care spending—implications for reform. N Engl J Med. 2010;362:460–465. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsb0911104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Localio AR, Goodman S. Beyond the usual prediction accuracy metrics: Reporting results for clinical decision making. Ann Intern Med. 2012;157:294–295. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-157-4-201208210-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Baker SG. Putting risk prediction in perspective: Relative utility curves. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2009;101:1538–1542. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djp353. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Vickers AJ, Cronin AM, Elkin EB, et al. Extensions to decision curve analysis, a novel method for evaluating diagnostic tests, prediction models and molecular markers. BMC Med Inform Decis Mak. 2008;8:53. doi: 10.1186/1472-6947-8-53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Vickers AJ, Elkin EB. Decision curve analysis: A novel method for evaluating prediction models. Med Decis Making. 2006;26:565–574. doi: 10.1177/0272989X06295361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ginsburg GS, Kuderer NM. Comparative effectiveness research, genomics-enabled personalized medicine, and rapid learning health care: A common bond. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30:4233–4242. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2012.42.6114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Riley RD, Sauerbrei W, Altman DG. Prognostic markers in cancer: The evolution of evidence from single studies to meta-analysis, and beyond. Br J Cancer. 2009;100:1219–1229. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6604999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kuderer N, Culakova E, Huang M, et al. Quality appraisal of clinical validation studies for multigene prediction assays of chemotherapy response in early-stage breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29(suppl):3083. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Micheel CM, Nass SJ, Omenn GS. Washington, D.C.: The National Academies Press; 2012. Evolution of Translational Omics: Lessons Learned and the Path Forward. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Febbo PG, Ladanyi M, Aldape KD, et al. NCCN task force report: Evaluating the clinical utility of tumor markers in oncology. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2011;9(suppl 5):S1–S32. doi: 10.6004/jnccn.2011.0137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.McShane LM, Altman DG, Sauerbrei W, et al. Reporting recommendations for tumor marker prognostic studies (remark) J Natl Cancer Inst. 2005;97:1180–1184. doi: 10.1093/jnci/dji237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Little J, Higgins JP, Ioannidis JP, et al. Strengthening the reporting of genetic association studies (STREGA): An extension of the STROBE statement. Ann Intern Med. 2009;150:206–215. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-150-3-200902030-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Moore HM, Kelly AB, Jewell SD, et al. Biospecimen reporting for improved study quality (BRISQ) Cancer Cytopathol. 2011;119:92–101. doi: 10.1002/cncy.20147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Teutsch SM, Bradley LA, Palomaki GE, et al. The evaluation of genomic applications in practice and prevention (EGAPP) initiative: Methods of the EGAPP working group. Genet Med. 2009;11:3–14. doi: 10.1097/GIM.0b013e318184137c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Goddard KA, Knaus WA, Whitlock E, et al. Building the evidence base for decision making in cancer genomic medicine using comparative effectiveness research. Genet Med. 2012;14:633–642. doi: 10.1038/gim.2012.16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Hoch JS, Hodgson DC, Earle CC. Role of comparative effectiveness research in cancer funding decisions in Ontario, Canada. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30:4262–4266. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2012.42.1958. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Sorenson C, Drummond M, Chalkidou K. Comparative effectiveness research: The experience of the national institute for health and clinical excellence. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30:4267–4274. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2012.42.1974. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Lyman GH, Levine M. Comparative effectiveness research in oncology: An overview. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30:4181–4184. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2012.45.9792. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Lyman GH, Hirsch B. Comparative effectiveness research and genomic personalized medicine. J Pers Med. 2010;7:223–227. doi: 10.2217/pme.10.18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Iglehart JK. Prioritizing comparative-effectiveness research—IOM recommendations. N Engl J Med. 2009;361:325–328. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp0904133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Pearson SD. Cost, coverage, and comparative effectiveness research: The critical issues for oncology. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30:4275–4281. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2012.42.6601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Calvert M, Blazeby J, Altman D, et al. Reporting of patient-reported outcomes in randomized trials: The CONSORT PRO extension. J Am Med Assoc. 2013;309:814–822. doi: 10.1001/jama.2013.879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]