Abstract

Background

Static postural instability is common in alcohol dependent individuals (ALC). Chronic alcohol consumption has deleterious effects on the neural and perceptual systems subserving postural stability. However, little is known about the effects of chronic cigarette smoking on postural stability and its changes during abstinence from alcohol.

Methods

A modified Fregly ataxia battery was administered to a total of 115 smoking (sALC) and non-smoking ALC (nsALC) and to 74 smoking (sCON) and non-smoking light/non-drinking controls (nsCON). Subgroups of abstinent ALC were assessed at 3 time points (approximately 1 week, 5 weeks, 34 weeks of abstinence from alcohol); a subset of nsCON was re-tested at 40 weeks. We tested if cigarette smoking affects postural stability in CON and in ALC during extended abstinence from alcohol, and we used linear mixed effects modeling to measure change across time points within ALC.

Results

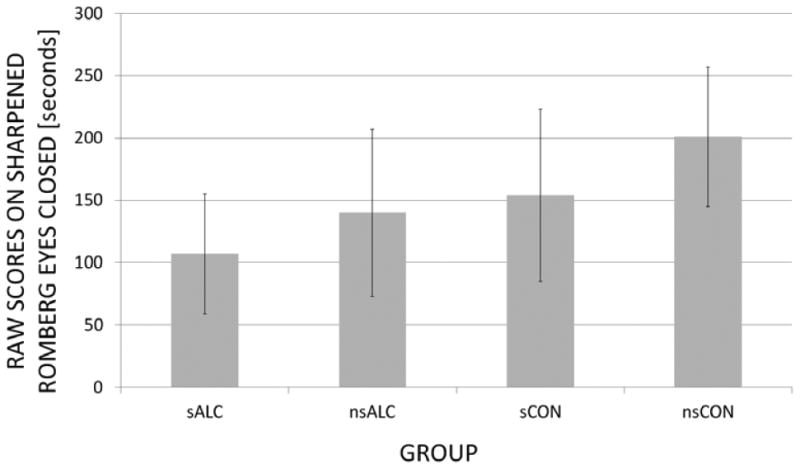

Chronic smoking was associated with reduced performance on the Sharpened Romberg eyes-closed task in abstinent ALC at all three time points and in CON. The test performance of nsALC increased significantly between 1 and 32 weeks of abstinence, whereas the corresponding increases for sALC between 1 and 35 weeks was non-significant. With long-term abstinence from alcohol, nsALC recovered into the range of nsCON and sALC recovered into the range of sCON. Static postural stability decreased with age and correlated with smoking variables but not with drinking measures.

Conclusions

Chronic smoking was associated with reduced static postural stability with eyes closed and with lower increases of postural stability during abstinence from alcohol. Smoking cessation in alcohol dependence treatment may facilitate recovery from static postural instability during abstinence.

Keywords: ataxia, balance, postural stability, alcohol dependence, cigarette smoking, abstinence

Introduction

Lower static postural stability is common among persons with alcohol use disorders (AUD) (Durazzo et al., 2006b; Sullivan et al., 2000b). Cross-sectional performance on ataxia tasks has been described at different lengths of sobriety within the first 12-18 months of abstinence from alcohol, with better gait and balance function after longer durations of sobriety (Smith and Fein, 2011). Longitudinal studies assessing performance on ataxia measures in abstinent alcohol dependent individuals (ALC) have yielded varying results depending on the duration of abstinence (Fein and Greenstein, 2013; Rosenbloom et al., 2004; Rosenbloom et al.; Sullivan et al.). Non-significant improvements were observed in ten abstinent ALC on an ataxia eyes-closed composite score between 4 months and 2 years of abstinence (Rosenbloom et al., 2007). Between 1 and 2 -12 months of abstinence, 20 ALC showed statistical trends for improvements on the Sharpened Romberg eyes-closed (SREC) task and on the Walk-on-Floor eyes-open task (Sullivan et al., 2000a). ALC, however, did not improve on these tasks and Stand-on-One-Leg when examined later between 10 weeks (n = 25) and up to 4 years (n = 13) of abstinence (Rosenbloom et al., 2004),(Fein and Greenstein, 2013). The generalizability of these longitudinal studies are limited by substance use comorbidities and rather small sample sizes at baseline and follow-up, the latter due to significant attrition from alcohol relapse.

Chronic cigarette smoking is highly comorbid with AUD, and 60-90% of treatment-seeking ALC are chronic smokers (Durazzo et al., 2007a; Hurt et al., 1994; Kalman et al., 2005; Le, 2002; Romberger and Grant, 2004). However, the potential effects of chronic smoking on static postural stability during abstinence from alcohol are poorly understood (Durazzo et al., 2006b). In treatment-naive individuals with AUD (Fein et al., 2012), smoking and non-smoking individuals did not differ significantly on the Romberg Stand-on-One-Leg and Walk-on-Floor tasks, neither with eyes open nor eyes closed. In 1-month-abstinent treatment seekers (Durazzo et al., 2006b), however, we found that smoking ALC (sALC) performed worse than non-smoking ALC (nsALC) on the SREC task, but not on the eyes-open condition, and that worse performance correlated with more cigarette smoked per day. Additionally, in middle-aged normal controls, chronic smokers showed significantly poorer performance than non-smokers on the SREC task, with worse performance in smokers related to more lifetime years of smoking (Durazzo et al., 2012b).

Given the lack of studies with larger samples in this area, our previous work on the effects of smoking on postural stability in normal controls and ALC (Durazzo et al., 2006a; Durazzo et al., 2012b; Durazzo et al., 2007b; Pennington et al., 2013) as well as the empirical (Cargiulo, 2007; Jahn et al., 2010; Stolze et al., 2008) and intuitive relevance of balance to quality-of-life and safety in everyday tasks, long-term assessment of a large cohort with repeated ataxia measures may advance our understanding of brain-behavior relationships following excessive alcohol consumption. Therefore, the goal of this study was to assess the effects of chronic smoking on postural stability in a large cohort of ALC over an average of 34 weeks of abstinence from alcohol and in matched non-alcoholic controls. We tested two primary hypotheses: (1) sALC demonstrate less recovery than nsALC on measures of static postural stability over the first 34 weeks of abstinence from alcohol; and (2) across ALC and CON, smokers perform worse than non-smokers on cross-sectional measures of static postural stability.

Materials and Methods

Participants

ALC were recruited from the VA Medical Center and the Kaiser Permanente substance abuse outpatient clinics in San Francisco. Controls (CON) were light/non-drinking individuals recruited from the local community, who had no history of biomedical and/or psychiatric conditions known to influence study measures. All research participants provided written informed consent according to the Declaration of Helsinki and underwent procedures approved by the University of California San Francisco and the San Francisco VA Medical Center. A total of 115 unique ALC participants were enrolled in this study. A subset of 67 ALC (40 sALC, 27 nsALC) was studied at 7±4 days of abstinence (time point 1=TP1); 100 ALC (59 sALC, 41 nsALC) were studied at an average of 33±9 days of abstinence (TP2), including 66 with TP1 data; 35 ALC (17 nsALC and 18 sALC) were studied after an average of 235±56 days (34 weeks) of abstinence (TP3) and all had TP2 data. Eighteen ALC had data for all three TPs. Seventy-four light drinking healthy controls (35 sCON and 39 nsCON) were studied with the same measures once; of these, 13 nsCON completed follow-up assessments 281±95 days after baseline to assess potential age-related effects on our measures, their stability over time, and potential practice effects. None of our smoking controls were studied twice. Descriptive data for the largest group of ALC participants (those participating at TP2 and representative of the whole cohort of 115 ALC) and our CON group are described in Tables 1-3.

Table 1. Group Demographics and Psychiatric History: Mean (SD) [min, max].

| Measure | nsALC | sALC | nsCON | sCON |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of participants (female) | 41 (7, 17%) | 59 (2, 3%) | 39 (7, 18%) | 35 (5, 14%) |

| Age [min, max] | 52 (10) [28, 67] | 49 (9) [28, 67] | 45 (9) [26, 59] | 49 (9) [33, 64] |

| Education (years) [min, max] | 15 (2) [12, 19] | 13 (2) [9, 20] | 16 (2) [12, 21] | 15 (2) [12, 20] |

| AMNART [min, max] | 115 (9) [95, 129] | 113 (9) [91, 128] | 120 (6) [101, 129] | 117 (6) [100, 128] |

| Percent Caucasian/African Amer./Latino/Asian/Polynesia n-Pacific Islander/Native Amer./Declined | 84/0/12/0/2/2/0 | 73/22/3/0/0/0/2 | 72/15/3/5/5/0/0 | 69/11/9/11/0/0/0 |

| Percent with current medical comorbidity | 52 | 47 | N/A | N/A |

| Percent with comorbid substance dependence (sustained full remission)/abuse (lifetime) diagnosis | 17/0 | 5/5 | N/A | N/A |

| Percent with current psychiatric comorbidity | 34 | 22 | N/A | N/A |

| Beck Depression Inventory [min, max] | 9 (9) [0, 31] | 11 (8) [0, 37] | 4 (4) [0, 13] | 6 (4) [0, 17] |

| State-Trait Anxiety Inventory – Trait [min, max] | 44 (11) [24, 62] | 44 (12) [21, 71] | 33 (7) [21, 47] | 33 (7) [20, 56] |

Note. nsALC: non-smoking alcohol dependent participant; sALC: smoking alcohol dependent participant; nsCON: non-smoking light-drinking control; sCON: smoking light-drinking control; NA: not applicable

Table 3. Group Smoking Variables: Mean (SD) [min, max].

| Measure | sALC | sCON |

|---|---|---|

| FTND at TP1 | 5.1 (1.8) [2, 10] | 5.0 (3.0) [2, 8] |

| FTND at TP2 | 5.1 (1.8) [2, 10] | N/A |

| FTND at TP3 | 5.1 (1.5) [2, 9] | 4.0 (3.0) [1, 6] |

| Cigarettes per day at TP1 | 19 (8) [2, 40] | 19 (10) [4, 30] |

| Cigarettes per day at TP2 | 19 (8) [2, 40] | N/A |

| Cigarettes per day at TP3 | 18 (6) [6, 30] | 11 (8) [4, 20] |

| Smoking duration (years) | 26 (12) [2, 54] | 25 (14) [5, 44] |

FTND: Fagerstrom Test of Nicotine Dependence;

NA: not applicable

Primary inclusion criteria for ALC were current DSM-IV-TR diagnosis of alcohol dependence, fluency in English, consumption of >150 standard alcoholic drinks per month for at least eight years before enrollment for men and >80 drinks per month for at least six years before enrollment for women. Primary exclusion criteria were fully detailed earlier (Durazzo et al., 2004). In brief, all participants were free of general psychiatric, neurological, and physical injuries to the back, hip, knees, and/or foot, and free of any medical conditions known or suspected to influence performance on a task of static postural stability, with the exceptions of hepatitis C, hypertension, and unipolar mood disorders. Major depression and substance-induced mood disorder were not exclusionary given their high comorbidity with both alcohol dependence (Gilman and Abraham, 2001) and chronic cigarette smoking (Fergusson et al., 2003). All subjects were specifically screened for history of peripheral neuropathies and vestibular disorders. In addition to self-report, the medical records of all ALC participants were reviewed prior to all time points to search for indications of any alcohol and other substance use (e.g., results of urine toxicology and alcohol breathalyzer tests). ALC who had consumed any amount of alcohol after TP1 or who stopped smoking after TP1 were not included in analyses at TP2 or TP3. All CON participants were screened for recent use of illicit substances, with smoking status and alcohol consumption history determined via self-report. For all participants, dependence on any drug in the past five years other than alcohol or nicotine was exclusionary. No participant was positive for alcohol or other substances at any time point.

Psychiatric/Behavioral Assessments

At the time of enrollment, all participants were administered the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV-TR Axis I Disorders, Patient Edition, Version 2.0 (1994), and standardized questionnaires assessing depressive (Beck Depression [BDI](Beck, 1978)) and anxiety symptomatologies (State-Trait Anxiety Inventory, Y-2 [STAI](Spielberger et al., 1977)), lifetime alcohol consumption (Lifetime Drinking History (Skinner and Sheu, 1982)), lifetime substance consumption (Abe et al., 2012) and level of nicotine dependence via the Fagerstrom Test for Nicotine Dependence (FTND) (Heatherton et al., 1991) (see Tables 1-3).

Postural Stability and Balance Assessments

To assess postural stability and balance, participants were administered a version of the Fregly ataxia battery (Durazzo et al., 2006b; Fregly and Graybiel, 1968; Fregly et al., 1972; Sullivan et al., 2000a). For the Sharpened Romberg, a measure of static postural stability, participants were required to stand heel-to-toe, with arms folded across the chest, for a maximum of 60 seconds, first with eyes open and then with eyes closed. The task was discontinued if participants were unable to maintain the required position for at least 3 seconds on any of the four trials. If they successfully maintained this position for 60 seconds on any of the four trials, they were given the maximum score of 60 for any remaining trials. For trials in which the 60 seconds criteria was not achieved, but the participant was able to maintain the required position for at least 3 seconds, the times were recorded and summed across all four trials to obtain the final total score. The maximum possible score for Sharpened Romberg eyes open or closed was 240 seconds.

For Walk-on-Floor Eyes-Open and Walk-on-Floor Eyes-Closed (WFEC), participants were required to walk heel-to-toe with arms folded across the chest and follow a straight line on the ground for 10 consecutive steps. The task was discontinued if the individual was unable to complete any one of three trials for eyes open or eyes closed. If a participant was able to complete all three trials, the total deviation in inches from the straight line at the end of 10 consecutive steps was summed across three trials. The maximum possible score for eyes open or eyes closed was zero inches. Raw scores were used for all analyses, as there are no appropriate norms for these balance and postural stability measures. In addition, standing-on-one-foot was attempted with ALC at TP1 but had to be discontinued early for safety reasons, particularly for the eyes-closed condition.

Data Analyses

Due to a restriction in the range of scores on the eyes-open tasks, our statistical analyses focused on the Sharpened Romberg Eyes-Closed (SREC). Additional analyses compared proportions of group members able to perform the WFEC task.

Longitudinal change on the SREC for sALC and nsALC over an average of 34 weeks of abstinence from alcohol was tested via linear mixed effects modeling (random intercepts and slopes with an autoregressive covariance structure). We specifically tested for an interaction of smoking status-by-duration of abstinence (in days) to determine if sALC and nsALC demonstrated a differential level of change during abstinence. . This linear mixed effects modeling is well-suited for evaluating longitudinal change in data sets that do not have identical numbers of observations for all cases (Pinheiro and Bates, 2000). Significant main effects and interactions were further examined via within-group comparison across time (i.e., days of abstinence) as indicated.

In cross-sectional analyses at each TP, we assessed alcohol status (ALC or CON)-by-smoking status (smoking or nonsmoking) interactions and main effects using univariate Analysis of Covariance (ANCOVA), controlling for age. We compared sALC and nsALC performance at all time points to baseline sCON and nsCON data. Initial comparisons between nsALC and sALC on the SREC were controlled for age, BDI (Bishop et al., 2009; laboni and Flint, 2013), and alcohol consumption variables, as these variables may influence postural stability. Only age emerged as a significant predictor of SREC performance and was therefore used as a covariate in all cross-sectional and longitudinal analyses directly comparing nsALC and sALC. Effect sizes (ES) for pairwise group comparisons were calculated using Cohen's d (Cohen, 1988). Unless otherwise indicated, all t-tests were 1-tailed as a priori hypotheses were tested. For tests that had ceiling effects (both eyes-open tasks) or could not be performed by the majority of participants for meaningful statistical analyses (WFEC), we performed Fisher's exact tests at each TP to assess for differences in proportion of individuals per group achieving maximum scores and being unable to perform the task. Correlations between performance on the SREC and smoking variables used Spearman rank testing. All statistical analyses were conducted with R v3.0.1 and SPSS v19; p<0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Characterization of Study Participants (see Tables 1-3)

Of the 100 ALC participants at TP2, 9 were female, 77 were Caucasian, 13 African American, seven Latino, one Native American, one Polynesian/Pacific Islander, and one declined to disclose ethnicity. nsALC had more years of education than sALC (p<0.001). The ALC groups were equivalent on age, AMNART score, total lifetime years drinking, and days of abstinence at TP1, TP2, and TP3 (all p>0.21). sALC drank more than nsALC over one year prior to study (+31%) and over lifetime (+36%, both p<0.001), and sALC began drinking heavily at a younger age than nsALC (22 vs 28 years, p<0.001). These alcohol consumption variables were not significant predictors of SREC performance in comparisons between nsALC and sALC . Of the 115 unique ALC participants in the study, nsALC and sALC did not differ on the densities of family history of nicotine dependence (p = 0.389) or on the densities of family history of problem drinking (p = 0.248), social drinking (p =0 .875) or abstinence from alcohol (p = 0.155) (only mother, father, and paternal and maternal grandparents were included in the density calculations). At TP2, which had the largest number of ALC participants, DSM-IV-TR criteria for recurrent major depression were met for 14/41 nsALC (34%) and 7/59 sALC (12%); four nsALC (10%) and two sALC (3%) met criteria for substance-induced (alcohol) mood disorder with depressive features. These percentages were similar for the ALC sample at TP1. Criteria for amphetamine dependence in full remission was met for 3/41 nsALC and 2/59 sALC (<8%); criteria for lifetime cocaine abuse was met for 3/59 sALC and no nsALC (<6%); criteria for cocaine dependence in full remission was met for 1/59 sALC and 3/41 nsALC (<8%). Hepatitis C antibody was present in 5/41 nsALC (12%) and 11/59 sALC (18%). The proportion of comorbid conditions was equivalent in smoking and non-smoking groups at all time points and did not contribute to variance on the task. The groups were not significantly different on BDI, STAI, or any other clinical laboratory variable at either time point. Total FTND scores were virtually identical across sALC samples at all TPs, indicating a stable and medium-to-high level of nicotine dependence during abstinence. One of the sALC participants stopped smoking after TP1 and was not included in any analyses of TP2 or TP3 data; none of the non-smoking participants started smoking during the study. Of the 74 CON participants at baseline, 12 were female (16%), 52 were Caucasian (70%), 10 African-American (14%), six Asian (8%), four Latino (5%), and two Polynesian/Pacific Islander (3%), a distribution statistically similar to that in ALC. nsCON were older than sCON (p=0.03) and had more years of education (p<0.001), but they were similar on alcohol consumption and other clinical variables. Smoking duration, number of cigarettes smoked per day, FTND score, and age were not significantly different between sCON and sALC (Table 3).

Longitudinal Changes on Sharpened Romberg Eyes-Closed in sALC and nsALC (see Table 4)

Table 4. Sharpened Romberg Eyes-Closed by Group: Raw scores in seconds for each time point (TP), mean (SD).

| Group | TP1 or Baseline | TP2 (5 weeks) | TP3 (mean 34 weeks) or nsCON follow-up (40 weeks) |

|---|---|---|---|

| sALC | 107 (48) | 118 (45) | 136 (58) |

| nsALC* | 140 (67) | 149 (77) | 185 (47) |

| sCON | 154 (69) | N/A | N/A |

| nsCON | 201 (56) | N/A | 203 (41) |

Significant change from TP1 to TP2 (p = 0.039) and from TP1 to TP3 (p = 0.026)

No smoking status-by-duration of abstinence interaction was observed for the SREC [t(81))=-0.27, p = 0.78]. However, there were significant main effects for smoking status [t(82)=-2.26, p=0.03] and duration of abstinence [t(82)=2.14, p=0.04] . Higher age was related to smaller increases in test performance with increasing abstinence [t(115)=-5.30, p < .001] Follow-up within group tests revealed nsALC and sALC showed differential changes in SREC performance over 34 weeks. nsALC showed a significant overall increase in SREC performance (p=0.03), whereas sALC showed no significant changes (p=0.22). Specifically, nsALC scores increased significantly between TP1-2 (p=0.04) and tended to increase between TP2-3 (p=0.08). By contrast, sALC showed no significant increases between any of the TPs (all p>0.21). When women were removed from the statistical analyses, the results were essentially unchanged and the pattern of findings virtually identical.

Cross-Sectional Findings on Sharpened Romberg Eyes-Closed (see Table 4)

At TP1, an alcohol status (ALC or CON)-by-smoking status (non-smokers or smoker) interaction was not observed. There were significant main effects for both alcohol (p<0.001) and smoking status (p=0.006). Specifically, sALC performed significantly worse than nsALC (p=0.034, ES=0.46, -25%), sCON (p=0.008, ES=0.56, -31%) and nsCON (p<0.001, ES=1.16, -47%); nsALC were inferior to nsCON (p=0.004, ES=0.65, -32%) but not significantly different from sCON (p=0.345, ES=0.10, -9%). sCON performed worse than nsCON (p=0.006, ES=0.60, -23%). Notably, smoking in CON contributed to a similar decrement in SREC performance than alcohol consumption in non-smokers, and the effects of smoking and drinking were approximately additive, i.e., sALC<nsALC∼sCON<nsCON (see Fig. 2).

Figure 2.

Group Performance on Sharpened Romberg Eyes-Closed (SREC): Raw scores (mean ± standard deviation) at TP1 or baseline

At TP2, there was also no alcohol status-by-smoking status interaction. Also at TP2, main effects for both group (p=0.001) and smoking status (p=0.002) were significant, with a similar pattern of group performance as at TP1, although with smaller effect sizes. Specifically, sALC performed significantly worse than nsALC (p=0.039, ES=0.42), sCON (p=0.035, ES=0.46) and nsCON (p<0.014, ES=1.00); nsALC were inferior to nsCON (p=0.014, ES=0.47), but not different from sCON (p=0.90).

In our main TP3 analyses we compared SREC performance in sALC and nsALC to SREC performance of sCON and nsCON measured at baseline. We did not observe a group-by-smoking status interaction. There was a significant main effect for smoking status (p=0.001), but not for alcohol status. After an average of 34 weeks of abstinence, we observed a pattern of results similar to that at 1 and 5 weeks, except that nsALC tended to perform better than sCON (p=0.062, ES=0.56). Overall, sALC performed significantly worse than both nsALC (p=0.046, ES=0.68) and nsCON (p<0.001, ES=0.78); but sALC were not different from sCON (p=0.541, ES = 0.28). nsALC at TP3 and nsCON performed similarly (p = 0.375, ES = 0.12). Since we had 40-weeks-follow-up data on 13 of the 40 nsCON individuals, we repeated the TP3 pairwise comparisons of the ALC groups to this smaller control group (that might have experienced “practice effects” similar to the ALC groups). Also here, sALC performed worse than both nsALC (p=0.025) and nsCON (p=0.016) with large effect sizes (ES = 0.69 and 0.81, respectively), whereas nsALC did not differ from nsCON (p=0.375, ES = 0.12). The significances and effect sizes of these group differences were very similar to those observed with the baseline data from the larger nsCON group. Again, removing female participants from these cross-sectional analyses left the results essentially unchanged.

Within the sALC group, worse SREC performance was related to greater lifetime years of smoking (r=-0.36, p=0.006 at TP2; r=-0.54, p=0.027 at TP3). Similarly in sCON, baseline SREC performance inversely correlated with lifetime years of smoking (r=-0.46, p=0.007).

Findings on Proportional Differences on Other Fregly Ataxia Tasks (see Table 5)

Table 5. Proportion of group participants with performance characteristics on three Fregly ataxia tasks.

| Group | Sharpened Romberg Eyes-Open: % with max score (total group n) | Walk-on-Floor Eyes-Open: % with max score (total group n) | Walk-on-Floor Eyes-Closed: % able to perform (total group n) |

|---|---|---|---|

| TP1 | |||

| sALC | 88 (40) | 90 (31) | 20 (35)a |

| nsALC | 93 (27) | 96 (23) | 48 (25) |

| sCON | 100 (35) | 94 (35) | 44 (32)b |

| nsCON | 95 (37) | 97 (36) | 86 (36) |

| TP2 | |||

| sALC | 93 (59) | 94 (52) | 29 (56)a |

| nsALC | 97 (41) | 83 (36) | 51 (37) |

| TP3 | |||

| sALC | 89 (18) | 87 (15) | 50 (14) |

| nsALC | 94 (17) | 86 (14) | 60 (15) |

| nsCON | 100 (13) | 88 (13) | 85 (13) |

sALC<nsALC proportion, p=0.03;

sCON<nsCON proportion, p<0.01

There were no differences among the proportions of smoking and non-smoking participants achieving maximum scores on the eyes-open tasks. However, fewer sALC than nsALC were able to perform the WFEC task at TP1 and TP2 (both p=0.03); this proportional difference was no longer apparent at TP3 after an average of 34 weeks of abstinence (see Fig 1). Similarly, the number of sCON able to perform the WFEC task at baseline was smaller than that of nsCON (44 vs. 86%, p<0.01). At TP3, the proportion of sALC able to perform the WFEC task was similar to that of sCON at baseline (50 vs. 44%, p=0.471). Similarly, the proportion of nsALC at TP3 and nsCON at follow-up able to perform the WFEC task were statistically equivalent (60 vs. 85%, respectively; p=0.567).

Figure 1.

Percent of group participants able to perform Walk-on-Floor Eyes-Closed at three time points (TP)

The proportion of sALC participants who improved on their ability to perform the WFEC task increased from 20% at one week to 50% at 35 weeks of abstinence (p=0.077), similar to the cross-sectional proportion of sCON (44%) who were able to perform the task. The corresponding proportion of nsALC able to complete the task increased from 48 % at TP1 to 60% at TP3, but this increase was not statistically significant(p=0.522); the nsALC performance at TP3 was similar to that in long-term abstinent sALC (50%).

Discussion

As hypothesized, static postural stability operationalized by the Sharpened Romberg Eyes-Closed task increased significantly in nsALC over 32 weeks of abstinence from alcohol into the performance range of nsCON with similar age. By contrast, sALC during abstinence did not exhibit statistically significant recovery on this measure of static postural stability over a similar time interval. Although sALC test scores increased into the performance range of age-matched sCON, their SREC performance after approximately 35 weeks of abstinence remained inferior to that of both nsCON and nsALC. Cross-sectionally, nsALC performed better than sALC at all three time points during abstinence; also among the non-alcoholic controls, nsCON performed better than sCON. Whereas performance was inversely correlated with smoking duration in both smoking groups, it was not related to alcohol consumption across both ALC groups. This is contrary to findings in treatment naive heavy drinkers (Smith and Fein, 2011). While the proportion of nsALC able to perform the WFEC task did not increase between TP1 and TP3 (similar to the nsCON proportion), the proportion of sALC able to perform the task more than doubled by TP3. Our analyses show that a) chronic smoking affects static postural stability with eyes closed, b) the bulk of recovery of static postural stability occurs during the initial several weeks of abstinence from alcohol, and c) the increases observed on a measure of static postural stability during abstinence are less pronounced in chronic smokers. The latter finding is consistent with the results of an exercise study in the elderly, in which current smokers improved less on self-reported balance and mobility (Bishop et al., 2009).

The SREC task interrogates the ability of the basal ganglia and cerebellum to integrate vestibular and proprioceptive information for maintaining postural stability in the absence of visual input (Maschke et al., 2003; Maschke et al., 2006). Accordingly, our results suggest that long-term abstinent sALC may be more prone than nsALC to balance-related physical risks due to dysfunction in the basal ganglia (Maschke et al., 2003; Maschke et al., 2006; Visser and Bloem, 2005), cerebellum (Manor et al., 2010; Maschke et al., 2006; Park et al., 2012; Rosenbloom et al., 2007) and/or vestibular (perceptual) systems (Horak, 2009), which are involved in proprioceptive feedback of position in extrapersonal space. Structural abnormalities of the cerebellum (Brody et al., 2004; Gallinat et al., 2006) (Yu et al., 2011) (Kuhn et al., 2012) and basal ganglia of smokers (Durazzo et al., 2012c; Liao et al., 2010; Yu et al., 2011) may mediate these balance problems. As such, the SREC task appears to be a simple, fast, and sensitive measure of interrogating in clinical and research settings the integrity of balance functions subserved by the basal ganglia and cerebellum and/or their interconnectivity. Additional long-term follow-up with this cohort may establish if SREC performance in this middle-aged cohort is predictive of fall risk later in life, and to see whether the ALC groups eventually achieve a level of performance that is fully equivalent to that of their non-alcoholic counterparts. In future studies, our findings in conjunction with neuroimaging of the basal ganglia and the cerebellum may be used to better understand the neuropathogenesis of postural instability associated with chronic drinking and smoking.

A few factors limit the generalizability of our results: Only one measure of static postural stability was used in this analysis due to ceiling effects or inability to perform on other ataxia measures. Postural sway measures (Sullivan et al., 2010) or functional gait assessments and tests of the balance evaluation systems (Leddy et al., 2011) could provide more robust and varied information in future studies of gait and balance. sCON were not re-tested and only a subset of nsCON was retested at follow-up. When comparing repeat data from ALC participants at TP2 and TP3 with baseline data obtained in CON, we did not control for potential practice effects in ALC. However, practice effects in the TP2-TP3 interval were likely minimized by the long interval between assessments and practice effects were not apparent in the nsCON subset re-studied after 40 weeks (see Table 4). Due to inability to participate at TP1 and attrition from relapse, all ALC participants did not contribute data at all time points during abstinence. However, analyses showed that the subgroups of ALC at TP1 and TP3 were representative of the largest group at TP2. The smaller number of observations at TP3 increases the risk of model over-fitting and corresponding Type I error, despite all critical model assumptions having been met in the longitudinal analyses of SREC change. Consistent with the main findings of these analyses, the visualization of complete longitudinal data from all three time points of 18 ALC individuals confirms qualitatively that nsALC recover more than sALC over an average of 34 weeks of abstinence. Finally, as the majority of study participants were Caucasian male veterans, race and gender effects could not be evaluated thoroughly.

Notwithstanding these limitations, our study is important in that it describes smoking-related deficits of static postural stability and balance in healthy controls and effects of smoking on these measures in a fairly large sample of ALC with low medical and substance use comorbidities during long-term abstinence from alcohol. Our findings suggest that abnormalities of static postural stability in sALC cannot be attributed solely to the effects of chronic and hazardous alcohol consumption, but that they are also related to chronic smoking. Specifically, chronic smoking in this cohort exerts nearly as large a decrement on static postural stability performance (∼24%) as chronic alcohol consumption (∼31%). Longitudinally, in this sample of middle-aged ALC, statistically significant recovery of static postural stability into the range of nsCON took approximately 8 months for nsALC On the other hand, sALC still retained performance deficits relative to nsALC at that time, and the longitudinal increases in sALC were not statistically significant although they showed recovery into the range of sCON.

Chronic cigarette smokers comprise 60-90% of treatment-seeking ALC (Durazzo et al., 2007a; Hurt et al., 1994; Kalman et al., 2005; Le, 2002; Romberger and Grant, 2004). The lack of a significant increase in scores on the SREC task by sALC over approximately 34 weeks of sustained abstinence may reflect persisting abnormalities of structure and/or biochemistry in the basal ganglia and/or cerebellum of sALC. In structural neuroimaging studies of these ALC participants at TP1, we observed that sALC relative to nsALC demonstrated larger putamen volumes (Durazzo et al., 2012c), a structure rich in nicotinergic acetylcholine receptors, but lower lenticular nuclei (globus pallidus + putamen) N-acetylaspartate concentration (a biomarker of neuronal viability)(Durazzo et al., 2004). The functional significance of these morphological and metabolite findings will be addressed in future analyses. Additionally, the lack of significant increases observed in sALC may indicate lower white matter microstructural integrity of pathways interconnecting the basal ganglia and cerebellum or those providing proprioceptive and/or vestibular input. As indicated by our previous longitudinal research on the neurobiological and neurocognitive effects of smoking in various populations (Durazzo et al., 2012a; Durazzo et al., 2013; Durazzo et al., 2006a; Durazzo et al., 2007b; Gazdzinski et al., 2010; Gazdzinski et al., 2008; Mon et al., 2009; Pennington et al., 2013), this new report provides additional impetus for studying the potentially beneficial effects of smoking cessation on neurobiology, cognition, and balance in alcohol use disorders and other conditions with high smoking comorbidities.

Table 2. Group Alcohol Variables: Mean (SD) [min, max].

| Measure | nsALC | sALC | nsCON | sCON |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of days abstinent at TP1 a | 6 (3) [1, 13] | 7 (5) [1, 30] | N/A | N/A |

| Number of days abstinent at TP2 a | 34 (9) [16, 58] | 33 (8) [16, 58] | N/A | N/A |

| Number of days abstinent at TP3 a | 225 (42) [139, 299] | 244 (70) [112, 413] | N/A | N/A |

| 1-yr average alcoholic drinks/month b | 309 (198) [20, 870] | 447 (253) [64, 1320] | 15 (16) [0, 60] | 21 (19) [0, 75] |

| Lifetime average alcoholic drinks/month b | 170 (104) [54, 532] | 267 (121) [45, 543] | 17 (14) [1, 51] | 25 (13) [4, 52] |

| Onset of heavy drinking [years] c | 28 (11) [15, 59] | 22 (7) [14, 50] | N/A | N/A |

| Duration of regular drinking [years] d | 35 (11) [10, 54] | 32 (9) [10, 49] | N/A | N/A |

p=n.s.;

p<0.001 for ALC;

heavy drinking=drinking in excess of 100 alcoholic drinks (containing 13.6 g of ethanol) per month for males (80 for females);

regular drinking=consuming at least one alcoholic drink per month;

NA: not applicable

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health [AA10788 to D.J.M.; DA24136 to T.C.D] administered by the Northern California Institute for Research and Education, and by the use of resources and facilities at the San Francisco Veterans Administration Medical Center. We thank Mary Rebecca Young, Kathleen Altieri, Ricky Chen, and Drs. Peter Banys, Steven Batki and Ellen Herbst of the Veterans Administration Substance Abuse Day Hospital,, and Dr. David Pating, Karen Moise and their colleagues at the Kaiser Permanente Chemical Dependency Recovery Program in San Francisco for their valuable assistance in recruiting participants. We also wish to extend our gratitude to the study participants, who made this research possible.

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest: The authors have no disclosures and no conflicts of interest to report.

Contributors: Drs. Dieter Meyerhoff and Timothy Durazzo conceptualized and designed the research and obtained funding for the project. Dr. Meyerhoff had central oversight and overall responsibility for all aspects of the research conducted by Mr. Schmidt and Dr. Pennington. Thomas Schmidt and Drs. Pennington and Durazzo recruited and assessed study participants and prepared all demographic, behavioral, and cognitive data. Dr. Durazzo conducted the statistical longitudinal data analyses and supervised Dr. Pennington on the other analyses. Dr. Pennington mentored Thomas Schmidt in analyzing and preparing the data, reviewing related literature, preparing figures and tables, and writing the first draft of the manuscript. All authors edited the manuscript.

References

- Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. 4th. American Psychiatric Association; Washington, D.C.: 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Abe C, Mon A, Durazzo TC, Pennington DL, Schmidt TP, Meyerhoff DJ. Polysubstance and alcohol dependence: Unique abnormalities of magnetic resonance-derived brain metabolite levels. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2012;130(l-3):30–7. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2012.10.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beck AT. Depression Inventory. Center for Cognitive Therapy; Philadelphia: 1978. [Google Scholar]

- Bishop MD, Robinson ME, Light KE. Tobacco use and recovery of gait and balance function in older adults. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2009;90(9):1613–8. doi: 10.1016/j.apmr.2009.02.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brody AL, Mandelkern MA, Jarvik ME, Lee GS, Smith EC, Huang JC, Bota RG, Bartzokis G, London ED. Differences between smokers and nonsmokers in regional gray matter volumes and densities. Biol Psychiatry. 2004;55(1):77–84. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(03)00610-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cargiulo T. Understanding the health impact of alcohol dependence. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2007;64(5 Suppl 3):S5–11. doi: 10.2146/ajhp060647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen J. Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; Hillsdale, NJ: 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Durazzo T, Insel PS, Weiner MW The Alzheimer's Disease Neuroimaging Initiative A. Greater regional brain atrophy rate in healthy elders with a history of cigarette smoking. Alzheimer's & Dementia. 2012a;8:513–519. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2011.10.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Durazzo TC, Abadjian L, Kincaid A, Bilovsky-Muniz T, Boreta L, Gauger GE. The influence of chronic cigarette smoking on neurocognitive recovery after mild traumatic brain injury. J Neurotrauma. 2013;30(11):1013–22. doi: 10.1089/neu.2012.2676. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Durazzo TC, Gazdzinski S, Banys P, Meyerhoff DJ. Cigarette smoking exacerbates chronic alcohol-induced brain damage: a preliminary metabolite imaging study. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2004;28(12):1849–60. doi: 10.1097/01.alc.0000148112.92525.ac. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Durazzo TC, Gazdzinski S, Meyerhoff DJ. The neurobiological and neurocognitive consequences of chronic cigarette smoking in alcohol use disorders. Alcohol Alcohol. 2007a;42(3):174–85. doi: 10.1093/alcalc/agm020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Durazzo TC, Gazdzinski S, Rothlind JC, Banys P, Meyerhoff DJ. Brain metabolite concentrations and neurocognition during short-term recovery from alcohol dependence: Preliminary evidence of the effects of concurrent chronic cigarette smoking. Alc Clin Exp Research. 2006a;30(3):539–51. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2006.00060.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Durazzo TC, Meyerhoff DJ, Nixon SJ. A comprehensive assessment of neurocognition in middle-aged chronic cigarette smokers. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2012b;122(1-2):105–11. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2011.09.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Durazzo TC, Mon A, Pennington D, Abe C, Gazdzinski S, Meyerhoff DJ. Interactive effects of chronic cigarette smoking and age on brain volumes in controls and alcohol-dependent individuals in early abstinence. Addict Biol. 2012c doi: 10.1111/j.1369-1600.2012.00492.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Durazzo TC, Rothlind JC, Gazdzinski S, Banys P, Meyerhoff DJ. A comparison of neurocognitive function in nonsmoking and chronically smoking short-term abstinent alcoholics. Alcohol. 2006b;39(1):1–11. doi: 10.1016/j.alcohol.2006.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Durazzo TC, Rothlind JC, Gazdzinski S, Banys P, Meyerhoff DJ. Chronic smoking is associated with differential neurocognitive recovery in abstinent alcoholic patients: a preliminary investigation. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2007b;31(7):1114–27. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2007.00398.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fein G, Greenstein D. Gait and balance deficits in chronic alcoholics: no improvement from 10 weeks through 1 year abstinence. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2013;37(1):86–95. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2012.01851.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fein G, Smith S, Greenstein D. Gait and Balance in Treatment-Naive Active Alcoholics with and without a Lifetime Drug Codependence. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2012;36(9):1550–62. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2012.01772.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fergusson DM, Goodwin RD, Horwood U. Major depression and cigarette smoking: results of a 21-year longitudinal study. Psychol Med. 2003;33(8):1357–67. doi: 10.1017/s0033291703008596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fregly AR, Graybiel A. An ataxia test battery not requiring rails. Aerospace Medicine. 1968;39:277–282. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fregly AR, Graybiel A, Smith MJ. Walk on floor eyes closed (WOFEC): a new addition to an ataxia test battery. Aerosp Med. 1972;43(4):395–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gallinat J, Meisenzahl E, Jacobsen LK, Kalus P, Bierbrauer J, Kienast T, Witthaus H, Leopold K, Seifert F, Schubert F, Staedtgen M. Smoking and structural brain deficits: a volumetric MR investigation. Eur J Neurosci. 2006;24(6):1744–50. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2006.05050.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gazdzinski S, Durazzo TC, Mon A, Yeh PH, Meyerhoff DJ. Cerebral white matter recovery in abstinent alcoholics--a multimodality magnetic resonance study. Brain. 2010;133(Pt 4):1043–53. doi: 10.1093/brain/awp343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gazdzinski S, Durazzo TC, Yeh PH, Hardin D, Banys P, Meyerhoff DJ. Chronic cigarette smoking modulates injury and short-term recovery of the medial temporal lobe in alcoholics. Psychiatry Research. 2008;162(2):133–45. doi: 10.1016/j.pscychresns.2007.04.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilman SE, Abraham HD. A longitudinal study of the order of onset of alcohol dependence and major depression. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2001;63(3):277–86. doi: 10.1016/s0376-8716(00)00216-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heatherton TF, Kozlowski LT, Frecker RC, Fagerstrom KO. The Fagerstrom Test for Nicotine Dependence: a revision of the Fagerstrom Tolerance Questionnaire. Br J Addict. 1991;86(9):1119–27. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.1991.tb01879.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horak FB. Postural compensation for vestibular loss. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2009;1164:76–81. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2008.03708.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hurt RD, Eberman KM, Croghan IT, Offord KP, Davis LI, Jr, Morse RM, Palmen MA, Bruce BK. Nicotine dependence treatment during inpatient treatment for other addictions: a prospective intervention trial. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 1994;18(4):867–72. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.1994.tb00052.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- laboni A, Flint AJ. The complex interplay of depression and falls in older adults: a clinical review. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2013;21(5):484–92. doi: 10.1016/j.jagp.2013.01.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jahn K, Zwergal A, Schniepp R. Gait disturbances in old age: classification, diagnosis, and treatment from a neurological perspective. Dtsch Arztebl Int. 2010;107(17):306–15. doi: 10.3238/arztebl.2010.0306. quiz 316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalman D, Morissette SB, George TP. Co-morbidity of smoking in patients with psychiatric and substance use disorders. Am J Addict. 2005;14(2):106–23. doi: 10.1080/10550490590924728. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuhn S, Romanowski A, Schilling C, Mobascher A, Warbrick T, Winterer G, Gallinat J. Brain grey matter deficits in smokers: focus on the cerebellum. Brain Struct Funct. 2012;217(2):517–22. doi: 10.1007/s00429-011-0346-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Le AD. Effects of nicotine on alcohol consumption. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2002;26(12):1915–6. doi: 10.1097/01.ALC.0000040963.46878.5D. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leddy AL, Crowner BE, Earhart GM. Functional gait assessment and balance evaluation system test: reliability, validity, sensitivity, and specificity for identifying individuals with Parkinson disease who fall. Phys Ther. 2011;91(1):102–13. doi: 10.2522/ptj.20100113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liao Y, Tang J, Liu T, Chen X, Hao W. Differences between smokers and non-smokers in regional gray matter volumes: a voxel-based morphometry study. Addict Biol. 2010 doi: 10.1111/j.1369-1600.2010.00250.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manor B, Hu K, Zhao P, Selim M, Alsop D, Novak P, Lipsitz L, Novak V. Altered control of postural sway following cerebral infarction: a cross-sectional analysis. Neurology. 2010;74(6):458–64. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e3181cef647. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maschke M, Gomez CM, Tuite PJ, Konczak J. Dysfunction of the basal ganglia, but not the cerebellum, impairs kinaesthesia. Brain. 2003;126(Pt 10):2312–22. doi: 10.1093/brain/awg230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maschke M, Gomez CM, Tuite PJ, Pickett K, Konczak J. Depth perception in cerebellar and basal ganglia disease. Exp Brain Res. 2006;175(1):165–76. doi: 10.1007/s00221-006-0535-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mon A, Durazzo TC, Gazdzinski S, Meyerhoff DJ. The Impact of Chronic Cigarette Smoking on Recovery From Cortical Gray Matter Perfusion Deficits in Alcohol Dependence: Longitudinal Arterial Spin Labeling MRI. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2009;33(8):1314–21. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2009.00960.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park IS, Yoon JH, Kim N, Rhyu IJ. Regional Cerebellar Volume Reflects Static Balance in Elite Female Short-Track Speed Skaters. Int J Sports Med. 2012 doi: 10.1055/s-0032-1327649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pennington DL, Durazzo TC, Schmidt T, Mon A, Abe C, Meyerhoff DJ. The Effects of Chronic Cigarette Smoking on Cognitive Recovery during Early Abstinence from Alcohol. Alc Clin Exp Research. 2013;37(7):1220–7. doi: 10.1111/acer.12089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pinheiro J, Bates D. Mixed-Effects Models in S and S-PLUS. Springer-Verlag; New York: 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Romberger DJ, Grant K. Alcohol consumption and smoking status: the role of smoking cessation. Biomed Pharmacother. 2004;58(2):77–83. doi: 10.1016/j.biopha.2003.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenbloom MJ, Pfefferbaum A, Sullivan EV. Recovery of short-term memory and psychomotor speed but not postural stability with long-term sobriety in alcoholic women. Neuropsychology. 2004;18(3):589–97. doi: 10.1037/0894-4105.18.3.589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenbloom MJ, Rohlfing T, O'Reilly AW, Sassoon SA, Pfefferbaum A, Sullivan EV. Improvement in memory and static balance with abstinence in alcoholic men and women: selective relations with change in brain structure. Psychiatry Res. 2007;155(2):91–102. doi: 10.1016/j.pscychresns.2006.12.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skinner HA, Sheu WJ. Reliability of alcohol use indices. The Lifetime Drinking History and the MAST. J Stud Alcohol. 1982;43(11):1157–1170. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1982.43.1157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith S, Fein G. Persistent but less severe ataxia in long-term versus short-term abstinent alcoholic men and women: a cross-sectional analysis. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2011;35(12):2184–92. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2011.01567.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spielberger CD, Gorsuch RL, Lushene R, Vagg PR, Jacobs GA. Self-Evaluation Questionaire 1977 [Google Scholar]

- Stolze H, Vieregge P, Deuschl G. Gait disturbances in neurology. Nervenarzt. 2008;79(4):485–99. doi: 10.1007/s00115-007-2406-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sullivan EV, Rose J, Pfefferbaum A. Mechanisms of postural control in alcoholic men and women: biomechanical analysis of musculoskeletal coordination during quiet standing. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2010;34(3):528–37. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2009.01118.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sullivan EV, Rosenbloom MJ, Lim KO, Pfefferbaum A. Longitudinal changes in cognition, gait, and balance in abstinent and relapsed alcoholic men: relationships to changes in brain structure. Neuropsychology. 2000a;14(2):178–88. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sullivan EV, Rosenbloom MJ, Pfefferbaum A. Pattern of motor and cognitive deficits in detoxified alcoholic men. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2000b;24(5):611–21. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Visser JE, Bloem BR. Role of the basal ganglia in balance control. Neural Plast. 2005;12(2-3):161–74. doi: 10.1155/NP.2005.161. discussion 263-72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu R, Zhao L, Lu L. Regional grey and white matter changes in heavy male smokers. PLoS One. 2011;6(11):e27440. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0027440. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]