Abstract

BACKGROUND

Heart failure is one of the leading causes of mortality, is a final common pathway of several cardiovascular diseases, and its treatment is a major concern in the science of cardiology. The aim of the present study was to compare the effect of addition of the coenzyme Q10 (CoQ10)/atorvastatin combination to standard congestive heart failure (CHF) treatment versus addition of atorvastatin alone on CHF outcomes.

METHODS

This study was a double-blind, randomized placebo-controlled trial. In the present study, 62 eligible patients were enrolled and randomized into 2 groups. In the intervention group patients received 10 mg atorvastatin daily plus 100 mg CoQ10 pearl supplement twice daily, and in the placebo group patients received 10 mg atorvastatin daily and the placebo of CoQ10 pearl for 4 months. For all patients echocardiography was performed and blood sample was obtained for determination of N-terminal B-type natriuretic peptide, total cholesterol, low density lipoprotein, erythrocyte sedimentation rate, and C-reactive protein levels. Echocardiography and laboratory test were repeated after 4 months. The New York Heart Association Function Class (NYHA FC) was also determined for each patient before and after the study period.

RESULTS

Data analyses showed that ejection fraction (EF) and NYHA FC changes differ significantly between intervention and placebo group (P = 0.006 and P = 0.002, respectively). Changes in other parameters did not differ significantly between study groups.

CONCLUSION

We deduce that combination of atorvastatin and CoQ10, as an adjunctive treatment of CHF, increase EF and improve NYHA FC in comparison with use of atorvastatin alone.

Keywords: Coenzyme Q10, Atorvastatin, Clinical Trial, Congestive Heart Failure

Introduction

Heart failure (HF) is one of the leading causes of mortality in the world and is a final common pathway of several cardiovascular diseases such as hypertension, myocardial infarction, volume overload, and cardiomyopathies.1,2

For the vast majority of patients, angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors (ACEI), angiotensin receptor blockers (ARB), beta-blockers, diuretics, and digoxin are the main treatment choices.3

Recent studies mentioned the role of oxidative stress and inflammation in the treatment of heart failure. Statins play an important role in lowering the pro-inflammatory markers in congestive heart failure (CHF) patients independent of their lipid lowering effect which triggered their use as an adjunctive therapy in CHF.4 Coenzyme Q10 (CoQ10) is a vitamin-like agent which is structurally similar to vitamin K.5 It was first isolated from beef mitochondria in 1957 and then found in other organs such as the heart, brain, and liver.6 CoQ10 is a fat soluble quinon which enhances cell membrane stabilization and mitochondrial energy production, and also has antioxidant effects.7,8 Recent studies have shown that statins have antioxidant activity, by means of activation of superoxide dismutase; moreover, some statins have been shown to reduce the endogenous CoQ10 levels through inhibition of 3-hdroxy 3-methyl glutaryl CoA reductase (HMG-CoA reductase).9

Previous studies showed that serum CoQ10 levels are lower in CHF patients than in the normal population which shows the importance of using its supplement in Patients with CHF.10

As mentioned above, statins and CoQ10 can be used as adjuncts in the treatment of CHF due to their anti-inflammatory and antioxidant effects, respectively. However, this matter remains a controversial issue.9,11-13 The aim of the present study was to compare the effect of the addition of atorvastatin/CoQ10 combination to standard CHF treatment with that of the addition of atorvastatin alone on CHF outcomes.

Materials and Methods

Trial design and participants

This study was a single centre, double blind, randomized, placebo-controlled clinical trial with parallel design which was performed in Chamran Hospital, a tertiary referral centre in Isfahan, Iran. During a period of 7 months, May 2012 to February 2013, 62 consecutive patients who met the inclusion criteria were enrolled in the study. Eligibility criteria were documented CHF, ejection fraction (EF) of less than 40%, compensated heart failure without hospital admission during the previous 3 months, no change in type and dose of medications in the last months, and New York Heart Association Function Class (NYHA FC) 2 to 4. Patients were excluded if any of the following criteria were present: acute coronary syndrome developing in the last month; active myocarditis; active pericarditis; uncontrolled hypertension; hepatic failure (Child B, C); pulmonary or renal failure; and heart failure with KILLIP classification 3 and 4.

Written informed consents were obtained from all patients for authorized use of their medical records for research purposes. Moreover, the protocol was approved by the ethical committee of our university.

In this study, a sample size of 30 in each group was calculated using statistical formula considering α = 0.05 and β = 0.2. This study was a double blind trial. For the purpose of blindness of patients, placebo was made with the same shape and size of the actual drugs, and for the blindness of physicians the drugs were delivered to patients by one of the study investigators who did not perform the echocardiography and determination of NYHA FC grade.

Intervention

Patients who enrolled in the study were randomly divided into 2 groups, using Random Allocation Software the sequence generation was performed by one of the study investigators who did not play a role in the clinical assessments and drug delivery to patients.14 Patients in the first group (intervention) received 10 mg atorvastatin (Abidi, Iran) daily plus CoQ10 pearl supplement (USA, manufactured in Sobhan, Isfahan, Iran) with the dose of 100 mg twice daily for 4 months. In the other group (placebo), patients received 10 mg atorvastatin daily and the placebo of CoQ10 pearl, with the same shape and size of the drug, for 4 months. Placebo pearls were produced in the School of Pharmacology of Isfahan University of Medical Sciences. In both study groups, patients received standard CHF medication. The drugs were delivered to patients by one of the study investigators. The dose of drugs used in this study was determined according to previous studies performed in this field.5

Assessments and outcomes

In all patients, baseline data including age, sex, weight, history of diabetes and myocardial infarction, previous use of beta blockers, and ACEI were collected. In the first visit, for each patient, echocardiography was performed using Vivid 7, USA device by one of the study investigators (JS) who was blinded to the patients’ group. EF and cardiac index (CI) were determined. Blood samples were taken and N-terminal B-type natriuretic peptide , total cholesterol (TC), low density lipoprotein (LDL), erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR), and C reactive protein (CRP) levels were recorded. NYHA FC was also determined for each patient. Glomerular filtration rate (GFR) was calculated. After the study period (4 months), echocardiography was repeated by the same device and the same investigator, NYHA FC was calculated for the second time, and laboratory tests were checked again in the same laboratory in which previous tests had been performed. The primary outcome of this study was the effect of the addition of the atorvastatin and CoQ10 combination supplement to standard regiment on cardiac EF, in comparison with atorvastin and placebo. Secondary outcomes were the comparison of change in NYHA FC, CI, NT-proBNP, TC, LDL, ESR, and CRP.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS for Windows (version 16; SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). Student’s t-test was used for parametric variables, chi-square test was used for nonparametric variables, and Man-Whitney test for data without normal distribution pattern. Statistical difference was considered significant if P < 0.05.

Results

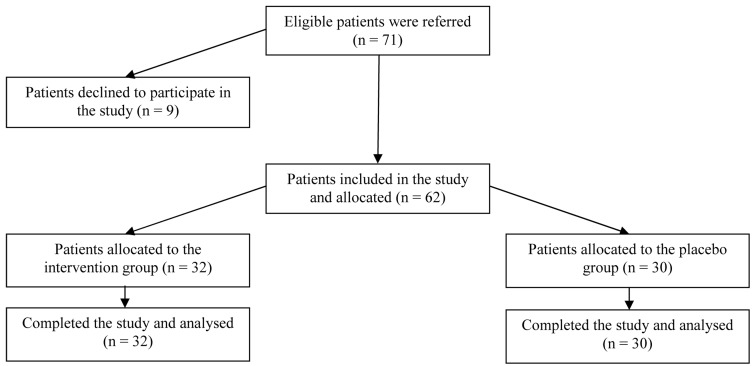

During the period of the project a total number of 62 patients were enrolled in the study. Patients’ enrolment, allocation, and follow up are shown in figure 1.

Figure 1.

Patients’ enrolment, allocation, and follow up

Demographic data in both study groups are shown and compared in table 1. There was no statistically significant difference in study parameters between the groups. All patients had used ACEI and beta blocker before the study began. After 4 months, all patients were alive and came back for follow up.

Table 1.

Demographic data in the study groups

| Intervention group (n = 32) | Placebo group (n = 30) | P | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 50.70 ± 12.5 | 54.47 ± 14.6 | 0.27 |

| GFR (ml/minute) | 72.29 ± 19.7 | 64.20 ± 20.7 | 0.12 |

| Male | 23 (71.9%) | 22 (73.3%) | 0.89 |

| History of diabetes | 7 (21.9%) | 11 (36.7%) | 0.20 |

| History of MI | 13 (40.6%) | 14 (46.7%) | 0.63 |

Data are presented as mean ± standard deviation and number (%); GFR: Glomerular filtration rate, MI: Myocardial infarction

Data analyses showed EF and NYHA FC changed significantly before and after the study period in the intervention group; however, these changes were not significant in the placebo group (P < 0.01 for both parameters). Other parameter changes did not differ significantly between the study groups. Detailed data are shown in table 2.

Table 2.

Comparison of parameters between study groups before and after the study period

| Intervention group | P | Placebo group | P | Mean’s difference | Standard error | P | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline | 4 months | Baseline | 4 months | ||||||

| EF | 18.7 ± 10.3 | 24.2 ± 14.5 | 0.003* | 26.2 ± 9.1 | 25.8 ± 9.7 | 0.23 | 5.98 | 2.11 | 0.006* |

| CI | 4.2 ± 1.7 | 4.4 ± 1.8 | 0.360 | 3.8 ± 1.4 | 4.0 ± 1.3 | 0.41 | -1.56 | 1.74 | 0.370 |

| NYHA FC | 2.7 ± 0.7 | 2.3 ± 0.7 | 0.025* | 2.9 ± 0.8 | 2.7 ± 0.7 | 0.17 | -0.48 | 0.15 | 0.002* |

| CRP | 3.7 ± 2.1 | 3.5 ± 2.3 | 0.130 | 4.6 ± 2.7 | 4.5 ± 3.3 | 0.22 | -0.14 | 0.40 | 0.900 |

| ESR | 13.6 ± 13.3 | 11.6 ± 15.2 | 0.110 | 6.7 ± 5.1 | 6.3 ± 4.6 | 0.31 | 1.83 | 5.76 | 0.750 |

| LDL | 106.7 ± 32.8 | 93.4 ± 29.3 | 0.150 | 87.4 ± 15.7 | 88.1 ± 16.0 | 0.42 | 0.02 | 0.34 | 0.930 |

| TC | 120.2 ± 39.7 | 114.2 ± 44.2 | 0.130 | 146.0 ± 40.1 | 138.2 ± 40.8 | 0.35 | -0.09 | 0.69 | 0.890 |

| NT-proBNP | 561.9 ± 293.7 | 541.6 ± 469.0 | 0.510 | 518.1 ± 218.5 | 484.6 ± 186.6 | 0.38 | 13.23 | 81.80 | 0.870 |

Data are presented as mean ± standard deviation; NYHA FC: New York Heart Association Functional Class; EF: Ejection fraction; CI: Cardiac index; CRP: C -reactive protein; ESR: Erythrocyte sedimentation rate; LDL: Low density lipoprotein; TC: Total cholesterol; NT-proBNP: N- terminal B-type Natriuretic Peptide

P < 0.05 considered significant

Discussion

The aim of the present study was to compare the effect of the addition of the CoQ10/atorvastatin combination to standard CHF treatment with that of the addition of atorvastatin alone on CHF outcomes. Our study results showed that EF, as the primary outcome of the study, increased significantly in the intervention group in comparison with the placebo group. Among secondary outcomes, NYHA FC decreased significantly in the intervention group in comparison with the placebo group.

Langsjoen and Langsjoen have evaluated heart failure outcome by the administration of CoQ10 supplement and found an increase in EF and notable clinical improvement by decrease in NYHA FC.15 In line with this study and several other studies, including a recent meta-analysis performed by Sander et al5, Okello et al9 and Fotino et al.16 in this field we found an increase in EF and decrease in NYHA FC. The effect of CoQ10 on EF can be explained in this way that CoQ10 reduces the reactive oxygen species which rise in heart failure; on other hand, CoQ10 reduces peripheral vascular resistance and improves the heart pomp to push blood.17-20

In a meta-analyses performed by sander et al., they mentioned that patients who use heart failure treatment, including ACEI, may not be gain benefit by using CoQ10 for EF improvement; however, in contrast with this study we found that in patients who are using ACEI drugs, EF increased by administration of CoQ10 supplement.5

Previous studies mentioned that CoQ10 supplement improves lipid profile. Shojaei et al., in their study, revealed that CoQ10 supplement reduces serum lipoprotein (a) level in patients using statin, but other serum lipids did not change significantly which can be due to the concomitant use of statin.21 In line with this study, our results showed that although there is reduction in TC and LDL, the difference of this change between study groups was not significant.

About the other markers, such as BNP, ESR, and CRP, although there was a decrease in their level, the difference between the 2 groups was not significant. In line with our study, the study by Okello et al. showed a decrease in pro-inflammatory markers by the administration of CoQ10 as an adjunctive treatment of heart failure.9

Our study also had a limitation; the follow up in our study was 4 months. Furthermore, studies with longer follow up period are recommended in order to evaluate survival rate.

In conclusion, we deduce that the combination of atorvastatin and CoQ10 as an adjunctive treatment of heart failure increase EF and improve NYHA FC in comparison with single use of atorvastatin. We did not found a difference in other parameters such as ESR, CRP, LDL, TC, NT-proBNP, and CI.

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest

Authors have no conflict of interests.

REFERENCES

- 1.Mishra P, Samanta L. Oxidative stress and heart failure in altered thyroid States. ScientificWorldJournal. 2012;2012:741861. doi: 10.1100/2012/741861. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Esfahani MA, Jolfaii EG, Torknejad M, Etesampor A, Amiz FR. Postprandial hypertriglyceridemia in non-diabetic patients with coronary artery disease. Indian Heart J. 2004;56(4):307–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pepe S, Marasco SF, Haas SJ, Sheeran FL, Krum H, Rosenfeldt FL. Coenzyme Q10 in cardiovascular disease. Mitochondrion. 2007;7(Suppl):S154–S167. doi: 10.1016/j.mito.2007.02.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sola S, Mir MQ, Lerakis S, Tandon N, Khan BV. Atorvastatin improves left ventricular systolic function and serum markers of inflammation in nonischemic heart failure. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2006;47(2):332–7. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2005.06.088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sander S, Coleman CI, Patel AA, Kluger J, White CM. The impact of coenzyme Q10 on systolic function in patients with chronic heart failure. J Card Fail. 2006;12(6):464–72. doi: 10.1016/j.cardfail.2006.03.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tran MT, Mitchell TM, Kennedy DT, Giles JT. Role of coenzyme Q10 in chronic heart failure, angina, and hypertension. Pharmacotherapy. 2001;21(7):797–806. doi: 10.1592/phco.21.9.797.34564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Molyneux SL, Florkowski CM, George PM, Pilbrow AP, Frampton CM, Lever M, et al. Coenzyme Q10: an independent predictor of mortality in chronic heart failure. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2008;52(18):1435–41. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2008.07.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Shekelle P, Morton S, Hardy ML. Effect of supplemental antioxidants vitamin C, vitamin E, and coenzyme Q10 for the prevention and treatment of cardiovascular disease. Evid Rep Technol Assess (Summ) 2003;(83):1–3. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Okello E, Jiang X, Mohamed S, Zhao Q, Wang T. Combined statin/coenzyme Q10 as adjunctive treatment of chronic heart failure. Med Hypotheses. 2009;73(3):306–8. doi: 10.1016/j.mehy.2009.03.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Freeman LM, Roubenoff R. The nutrition implications of cardiac cachexia. Nutr Rev. 1994;52(10):340–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1753-4887.1994.tb01358.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Khatta M, Alexander BS, Krichten CM, Fisher ML, Freudenberger R, Robinson SW, et al. The effect of coenzyme Q10 in patients with congestive heart failure. Ann Intern Med. 2000;132(8):636–40. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-132-8-200004180-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Berman M, Erman A, Ben-Gal T, Dvir D, Georghiou GP, Stamler A, et al. Coenzyme Q10 in patients with end-stage heart failure awaiting cardiac transplantation: a randomized, placebo-controlled study. Clin Cardiol. 2004;27(5):295–9. doi: 10.1002/clc.4960270512. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rosenfeldt F, Hilton D, Pepe S, Krum H. Systematic review of effect of coenzyme Q10 in physical exercise, hypertension and heart failure. Biofactors. 2003;18(1-4):91–100. doi: 10.1002/biof.5520180211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Saghaei M. Random allocation software for parallel group randomized trials. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2004;4:26. doi: 10.1186/1471-2288-4-26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Langsjoen PH, Langsjoen AM. Supplemental ubiquinol in patients with advanced congestive heart failure. Biofactors. 2008;32(1-4):119–28. doi: 10.1002/biof.5520320114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fotino AD, Thompson-Paul AM, Bazzano LA. Effect of coenzyme Q(1)(0) supplementation on heart failure: a meta-analysis. Am J Clin Nutr. 2013;97(2):268–75. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.112.040741. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hodgson JM, Watts GF. Can coenzyme Q10 improve vascular function and blood pressure? Potential for effective therapeutic reduction in vascular oxidative stress. Biofactors. 2003;18(1-4):129–36. doi: 10.1002/biof.5520180215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pacher P, Schulz R, Liaudet L, Szabo C. Nitrosative stress and pharmacological modulation of heart failure. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 2005;26(6):302–10. doi: 10.1016/j.tips.2005.04.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ferrari R, Guardigli G, Mele D, Percoco GF, Ceconi C, Curello S. Oxidative stress during myocardial ischaemia and heart failure. Curr Pharm Des. 2004;10(14):1699–711. doi: 10.2174/1381612043384718. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.van den Heuvel AF, van Veldhuisen DJ, van der Wall EE, Blanksma PK, Siebelink HM, Vaalburg WM, et al. Regional myocardial blood flow reserve impairment and metabolic changes suggesting myocardial ischemia in patients with idiopathic dilated cardiomyopathy. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2000;35(1):19–28. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(99)00499-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Shojaei M, Djalali M, Khatami M, Siassi F, Eshraghian M. Effects of carnitine and coenzyme Q10 on lipid profile and serum levels of lipoprotein(a) in maintenance hemodialysis patients on statin therapy. Iran J Kidney Dis. 2011;5(2):114–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]