To the Editor

Despite having 24-hour access to healthcare professionals, nursing home residents have disproportionately high rates of emergency department (ED) visits, a large portion of which are potentially preventable.1,2 These potentially preventable acute care visits, often classified using ambulatory care sensitive conditions (ACSCs), can actually be harmful to residents’ functional outcomes relative to treatment in their familiar setting.3 Given the increase in reporting and enforcement of the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services’ (CMS’s) regulations on nursing home quality, we hypothesized that the rate of ED visits for ACSCs by elderly nursing home patients declined over the last decade.

Methods

We conducted a retrospective analysis of ED visits by elderly nursing home residents using data from the 2001–2010 National Hospital Ambulatory Medical Care Survey. We excluded patients who were <65 years old (85%), died in the ED (0.5%), or did not reside in a nursing home (88.8%) (See eMethods).

We used the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality’s Prevention Quality Indicators to identify visits for ACSCs based on ICD-9 diagnosis codes. To calculate rates of ED use per nursing home resident we used resident-year denominators from CMS’s Online Survey Certification and Reporting data.

Significance of the trends in rates of ED visits for both ACSCs and other diagnoses by nursing home patients was assessed using Poisson regression. We further analyzed the distribution of visits for ACSCs by diagnosis, and assessed the significance of changes in that distribution using a chi-square test over five two-year blocks to preserve significant sample sizes.

All analyses were performed using SAS version 9.2 and Sudaan version 10.0. This study was exempt from review by the UCSF Committee on Human Research.

Results

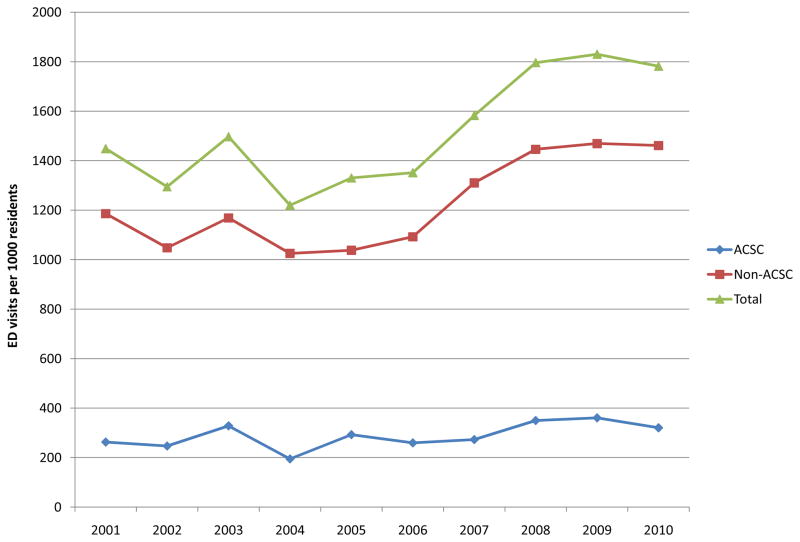

Between 2001 and 2010, the number of ED visits by elderly nursing home patients increased 12.8%, from 1.9 to 2.1 million. Nineteen percent were for ACSCs. The rate of ED visits for ACSCs increased from 263 to 320 visits per 1000 residents (21.8%), but the change was not statistically significant (Figure; p=0.93). The increase in the rate of ED use for non-ACSCs, from 1186 to 1461 visits per 1000 residents (23.2%), was also non-significant (p=0.94). The relative rate of ED visits for ACSCs to visits for other diagnoses remained relatively constant, fluctuating around 0.22.

Figure.

Rates of Emergency Department Visits per 1000 U.S. Nursing Home Residents Overall, for Ambulatory Care Sensitive Conditions (ACSCs), and for Non-ACSCs, 2001–2010a

aVisit numbers and thus corresponding visit rates from 2001–2004 were adjusted by 0.92 to account for non-nursing home, institutionalized patients (See eMethods).

Pneumonia was the most common ACSC in the sample, accounting for 28% of all ED visits for ACSCs (Table). Urinary tract infections rose from 23% of all visits for ACSCs in 2001–2002 to 33% in 2009–2010, though the change in the distribution of diagnoses was not significant (p=0.17).

Table.

Number and Percent of Emergency Department Visits for ACSCs by Diagnosis Among Elderly Nursing Home Residents

| Visits for ACSCs N (column %) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2001–2002a | 2003–2004a | 2005–2006 | 2007–2008 | 2009–2010 | |

| Pneumonia | 184,546 (27.9%) | 220,025 (33.1%) | 168,422 (24.4%) | 233,158 (30.5%) | 281,640 (34.4%) |

| Urinary Tract Infection | 154,941 (23.4%) | 157,030 (23.6%) | 226,072 (32.8%) | 209,926 (27.5%) | 272,865 (33.4%) |

| Other ACSCb | 322,924 (48.7%) | 287,876 (43.3%) | 295,067 (42.8%) | 320,853 (42.0%) | 263,395 (32.2%) |

Visit estimates in 2001–2004 are weighted by 0.92 (see eMethods)

Other includes asthma, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, hypertension, appendicitis, congestive heart failure, dehydration, angina, and diabetes complications

Legend: Upon analysis of the change in distribution of diagnoses using a chi-square test, we found that the shift in visits across diagnosis groups over the study period was not significant (p=0.17).

Discussion

Despite increasing legislation to monitor and enforce nursing home standards and quality of care, there has been no decrease in the rate of ED visits for ACSCs over the past decade. The absolute rate of ED visits for ACSCs among elderly nursing home residents (273 visits per 1000 in 2007) was substantially higher than past estimates of ED visit rates for ACSCs in the general adult population (31.9 per 1000 in 2007).4 Similarly, their overall ED visit rate (1310 per 1000 in 2007) was almost three times higher than past estimates of ED utilization by all Americans over 65 (476.8 per 1000 in 2007).4

High ED visit rates among elderly nursing home residents are in some ways expected, both for ACSCs and overall, given the prevalence of serious illness and disability in this population.5 Further, the uncoordinated payment systems of Medicare and Medicaid, for which most elderly nursing home patients are dual eligible, can actually incentivize these transfers.5 Past studies have shown that reducing these potentially preventable visits has the potential to generate significant savings for these public insurance programs.6

Acknowledgments

We especially thank Amy Markowitz, JD for her insightful comments on the manuscript. Dr. Hsia had full access to all of the data in the study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis. This project was supported by the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences, National Institutes of Health, through UCSF-CTSI Grant Number KL2 TR000143 (R.Y.H), and the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation Physician Faculty Scholars Program (R.Y.H.). The sponsors had no role in the design and conduct of the study, in the collection, analysis, and interpretation of data, or in the preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript.

Footnotes

The authors have no conflicts of interest to report.

References

- 1.Wang HE, Shah MN, Allman RM, Kilgore M. Emergency department visits by nursing home residents in the United States. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2011;59(10):1864–1872. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2011.03587.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Caffrey C. Potentially preventable emergency department visits by nursing home residents: United States, 2004. NCHS Data Brief. 2010 Apr;(33):1–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fried TR, Gillick MR, Lipsitz LA. Short-term functional outcomes of long-term care residents with pneumonia treated with and without hospital transfer. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1997;45(3):302. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1997.tb00944.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tang N, Stein J, Hsia RY, Maselli JH, Gonzales R. Trends and Characteristics of U.S. Emergency Department Visits, 1997–2007. JAMA. 2010;304(6):664–670. doi: 10.1001/jama.2010.1112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Vladeck BC. The continuing paradoxes of nursing home policy. JAMA. 2011;306(16):1802–1803. doi: 10.1001/jama.2011.1527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Grabowski DC, O’Malley AJ, Barhydt NR. The costs and potential savings associated with nursing home hospitalizations. Health Aff (Millwood) 2007;26(6):1753–1761. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.26.6.1753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]