Editor—Fergusson et al consider a trial to be double blind when the patient, investigators, and outcome assessors are unaware of the patient's assigned treatment throughout the conduct of the trial.1 They are quite wrong to do so.

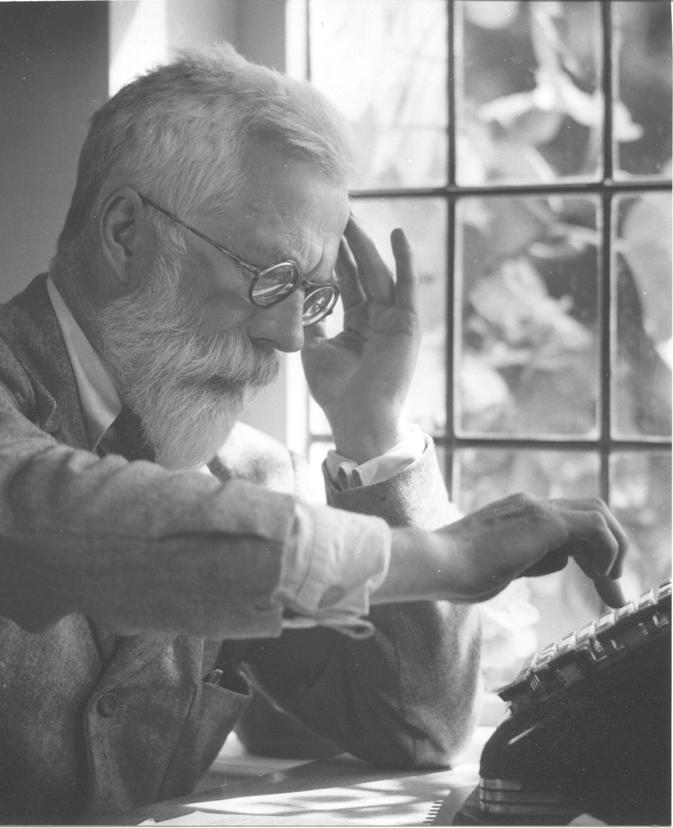

Figure 1.

R A Fisher (1890-1962)

Credit: A C BARRINGTON BROWN

The whole point of a successful double blind trial is that there should be unblinding through efficacy. That is to say that there should be no incidental reasons, apart from efficacy, as to why the treatments are distinguishable but that the treatments should reveal themselves through efficacy. If the treatments are not distinguishable at all, then the treatments have not been proved different.

The classic description of a blind experiment is Fisher's account of a woman tasting tea to distinguish which cups have had milk in first and which cups have had tea in first in support of her claim that the taste will be different.2 Here the efficacy of the treatment, order of milk or tea, is “taste” and the lady's task is to distinguish efficacy. Fisher describes the steps, in particular randomisation, that must be taken to make sure that the woman is blind to the treatment.3 But if he were to adopt the point of view of Fergusson et al, there would be no point in running the trial, since if the woman distinguishes the cups, the trial will be declared inadequate, as she has clearly not been blind throughout the trial.

Of course, in a parallel group trial, the patients only have one treatment. But not unreasonably in such a trial every patient who has had a good outcome might guess, with no other grounds to go on than outcome, that she was on active treatment and every patient with an unsatisfactory outcome might guess that she was on placebo. If the treatment is effective the guesses will distribute unequally between the arms of the trial and the trial will then be declared “not blind.” Fergusson et al seem to have a blinkered view of blinding. Their proposals are illogical and need rethinking.

Competing interests: SJS is a consultant to the pharmaceutical industry.

References

- 1.Fergusson D, Cranley Glass K, Waring D, Shapiro S. Turning a blind eye: the success of blinding reported in a random sample of randomised, placebo controlled trials. BMJ 2004;328: 432. (21 February.) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fisher RA. The design of experiments. In: Bennet JH, ed. Statistical methods, experimental design and scientific inference. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1935.

- 3.Senn SJ. Dicing with death. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2003.