Abstract

Background: Depressive and anxiety disorders are highly prevalent in the primary care setting. There is evidence that patients with depression and comorbid anxiety are more severely impaired than patients with depression alone and require aggressive mental health treatment. The goal of this study was to assess the impact of comorbid anxiety in a primary care population of depressed patients.

Method: 342 subjects diagnosed with a DSM-IV–defined major depressive episode, dysthymia, or both were asked 2 questions about the presence of comorbid anxiety symptoms (history of panic attacks and/or flashbacks). Patient groups included depression only (N = 119), depression and panic attacks (N = 51), depression and flashbacks (N = 97), and depression and both panic attacks and flashbacks (N = 75). Groups were compared on demographics, mental health histories, and health-related quality-of-life variables. Data were gathered from January 1998 to March 1999.

Results: Those patients with depression, panic attacks, and flashback symptoms as compared with those with depression alone were more likely to be younger, unmarried, and female. The group with depression, panic attacks, and flashbacks was also more likely to have more depressive symptoms, more impaired health status, worse disability, and a more complicated and persistent history of mental illness. Regression analysis revealed that the greatest impact on disability, presence of depressive symptoms, and mental health outcomes was associated with panic attacks.

Conclusion: By asking 2 questions about comorbid anxiety symptoms, primary care providers evaluating depressed patients may be able to identify a group of significantly impaired patients at high risk of anxiety disorders who might benefit from collaboration with or referral to a mental health specialist.

Major depression and anxiety disorders frequently occur in the primary care setting. The prevalence of major depression has been reported to range between 5% and 10% in the primary care setting.1 Commonly occurring anxiety disorders in the primary care setting include panic disorder and posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD). The prevalence of panic disorder in this setting has been reported to range between 6.7% and 8.3%.2 Posttraumatic stress disorder, once thought to be common only in Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) populations, has now been reported to be common in the non-VA primary care setting with a reported prevalence of 11.8%.3 Treatment approaches for major depression, panic disorder, and PTSD have been developed for the primary care setting.4–6

Given the high prevalence of these disorders in primary care populations, it is not surprising to find them frequently occurring as comorbid disorders. The prevalence of panic disorder in patients with depression has been reported to be approximately 10%.7 Whereas the prevalence of PTSD in patients with depression is not clearly known, the prevalence of depression in patients with PTSD has been reported to be as high as 60%.3

Patients with depression and comorbid anxiety disorders have been shown to have significantly worse morbidity than those without comorbid anxiety disorders, including worse symptom severity, greater functional impairment, fewer social contacts, greater use of health care resources, and higher rates of suicide attempts.8–17 Studies have also shown that subsyndromal anxiety and depression are highly prevalent in the primary care setting and that patients with subsyndromal anxiety and depression suffer significant impairment.18–20 These findings have led to the suggestion that primary care providers should routinely screen for anxiety disorders in their depressed patients because early diagnosis and treatment of these comorbid disorders may lead to a better treatment response.15,20 However, the primary care provider is already overburdened and under time pressure and may not feel adequately skilled to assess for a wide range of mental health disorders.

We were interested in finding out if a subpopulation of depressed primary care patients with comorbid anxiety symptoms and substantial functional impairment could be identified. To address this question, we planned to look at the role of comorbid anxiety symptoms in a population of patients enrolled in a trial evaluating treatment of depression in a primary care setting.21 Prior to this depression treatment trial, comorbid anxiety was considered to be one of the factors that could influence the effectiveness of treatment for depressed patients in a primary care setting. We hypothesized that patients diagnosed with major depression who answered yes to a question about panic attacks and/or a question about flashbacks would have higher depression severity, worse course of depression, and more functional impairment than depressed patients without these anxiety symptoms.

METHOD

Setting

The patients evaluated for this study were part of the Effectiveness of Team Treatment of Depression in VA Primary Care trial, a randomized trial of the effectiveness of the collaborative care model to treat depression in the primary care setting.21 Human Subjects Committee approval was obtained for this study and all work that used data from this study, and all subjects provided written informed consent to participate. At the VA Puget Sound Health Care System (Seattle, Wash.), primary care is provided in the General Internal Medicine Clinic (GIMC). The GIMC is organized into firms to which primary care providers and their patient panels are assigned in an unbiased manner. For the Effectiveness of Team Treatment trial, these firms were randomly assigned to collaborative care or usual care study arms. Data were gathered from January 1998 to March 1999.

Sample

Patients referred to the Effectiveness of Team Treatment trial had screened positive for clinically significant depressive symptoms. After initial screening, each prospective subject was administered a computer-assisted structured interview assessing depression severity, current or past use of medication or therapy, health status, current and past alcohol use, PTSD symptoms, history of mental illness, and barriers to care. Depression and anxiety symptom assessment was based on the Primary Care Evaluation of Mental Disorders22 with additional questions taken from the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV.23 Alcohol use was assessed with the CAGE, a quantity- frequency index, and questions about the patient's perception of substance use.24 The interview was administered by a skilled psychology technician in person or by telephone. Previous studies have found high concordance between in-person and telephone structured depression assessment.25

For the Effectiveness of Team Treatment trial, eligible patients were required to meet Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition, (DSM-IV) criteria for a current major depressive episode, dysthymia, or both.26 Exclusion criteria were as limited as possible to increase generalizability of results across the primary care population. Patients with recent mental health specialty visits and a scheduled future appointment were excluded, as we did not want to interfere in ongoing intensive mental health treatment. Patients who were judged to require treatment for substance abuse prior to initiating depression treatment were excluded and referred to a specialty clinic (N = 43). Patients with well-known primary PTSD were excluded prior to initiating treatment for depression and were referred to a specialty clinic (N = 11). Eleven other patients were excluded because of acute suicidality, psychosis, or other conditions requiring immediate treatment. We enrolled 168 patients in the collaborative care arm and 186 patients in the usual care arm for a total of 354 patients. For our analysis, we analyzed 342 patients. Twelve patients had to be dropped from the original sample due to missing data.

Subjects for this depression and comorbid anxiety study were selected from both arms of the Effectiveness of Team Treatment trial. This group of depressed patients was divided into groups based on the presence or absence of comorbid anxiety symptoms. We chose clinically significant anxiety symptoms that are consistent with panic disorder and PTSD. These symptoms were chosen because panic disorder and PTSD have been shown to be prevalent in the primary care setting and are associated with significant morbidity. We chose 1 symptom to represent each of these anxiety disorders. For panic disorder, we chose “Have you had anxiety or panic attacks in the last month?” For PTSD, we chose a question that is suggestive of flashbacks: “Have you been bothered by images in the last month?” We are unaware of any data on the specificity or sensitivity of these 2 items as screening questions. We chose these 2 questions in an attempt to probe for subjects who may be suffering from comorbid anxiety symptoms or disorders. It should be clear that these 2 questions were asked by the psychology technician as part of a total package of questions and were not asked as a 2-question screen by primary care providers. We realized that we would be unable to accurately identify panic disorder or PTSD with these 2 questions. We then grouped the patients into those with depression alone (N = 119), those with depression and the panic attack symptom (N = 51), those with depression and the PTSD symptom (N = 97), and those with depression and both the panic and PTSD symptoms (N = 75).

Measures

Measures used were those administered at baseline (within 1 week of study enrollment) of the Effectiveness of Team Treatment trial. The Hopkins Symptom Checklist depression scale (SCL-20) measured depressive symptomatology. The SCL-20 includes the 20 depression items from the Symptom Checklist-90.27 Health status was measured with the Veterans Short Form 36 (SF-36) Health Status Questionnaire.28,29 This assessment can be scored as 8 subscales and 2 summary scores: a physical component scale (PCS) and a mental component scale (MCS). The Sheehan Disability Scale30 was also used. This 3-item questionnaire examines how diminished health status interferes with work/school, family life, and social life and activities on a 0-to-10 Likert scale. We used the VA version of the Chronic Disease Score (CDS),31,32 a measure of chronic medical illness based on medication data, to describe overall disease burden at enrollment. This measure has been found to have a high correlation with physician ratings of severity of illness and to predict hospitalization and mortality in the year following assessment after controlling for age, sex, and health care visits.32

Data Analysis

To assess the independent predictive capacity of the panic and flashback symptoms, we fit multivariate linear regression models using (separately) PCS, MCS, Sheehan, or SCL-20, measured at baseline, as the response variable. In adjusted analysis, we controlled for the demographic variables listed in Table 1. For each outcome, we fit both an additive regression model that assumed a constant effect of both the panic and flashback symptoms and a saturated model that included the interaction between the panic and flashback symptoms. The model with interaction allowed a different effect of panic based on whether a subject reported the flashback symptom (and similarly a different effect of flashback depending on whether a subject reported panic). We formally tested whether the interaction between panic and the flashback symptom was statistically significant using a standard t test of the interaction regression coefficient. When the interaction was not statistically significant, we could report a separate panic and flashback effect on the mean response.

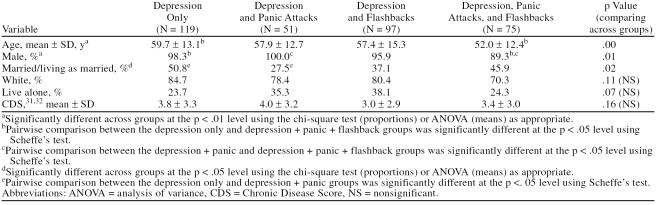

Table 1.

Demographic Variables by Group in 342 Patients With Depression

RESULTS

Demographic information about patients in each of the 4 groups is presented in Table 1. Analysis of variance showed that patients in the 4 groups were not significantly different with respect to ethnic backgrounds, whether they lived alone or with others, or CDS. Groups differed from one another with respect to age, gender, and marital status. The group with depression and the panic attack and flashback symptoms was significantly younger than the depression alone group. The group with depression and the panic and flashback symptoms was significantly more likely to be female compared with the depression alone group and the depression plus panic attack symptom group. The group with depression alone was significantly more likely to be married compared with the depression plus panic attack symptom group.

Comparisons across groups on health status using the SF-36 (Table 2) found that the group with depression, panic attacks, and flashbacks had significantly lower scores (p < .05) than the depression alone group on all subscales of the SF-36 except for physical functioning, the general health subscales, and the PCS. These unadjusted differences were considered clinically significant using the standard assessment of a clinically significant difference as being 5 points or more.28,29 The depression and panic attack group scored statistically and clinically lower than the depression group on social functioning, role-emotional, mental health, and the MCS.

Table 2.

Health-Related Quality-of-Life Measures at Baseline by Group in Patients With Depression (mean ± SD)

Scores from the composite scale and all subscales of the Sheehan Disability Scale showed that the group with the least disability was the depression group. The other groups with comorbid anxiety symptoms all had worse scores on these disability scales. Analysis of variance across these groups revealed a significant difference across groups (p < .05). Pairwise comparisons (Scheffe's test) revealed that the group with depression, panic attacks, and flashbacks had significantly worse scores for the composite scale and all subscales as compared with the depression group (p < .01).

Depression symptom severity was assessed by comparing SCL-20 scores for the groups. Values greater than 1.72 reflect clinically significant depressive severity.33 The group with depression, panic attacks, and flashbacks had the greatest depressive symptom severity with a mean score of 2.23. The depression and panic attack group mean score was 2.05, the depression and flashback group mean score was 1.83, and the depression group mean score was 1.63. The differences across groups were significant (p < .01). Pairwise comparisons revealed that the depression, panic attack, and flashback group had significantly worse depressive symptomatology compared with the depression group and the depression and flashback group (p < .05).

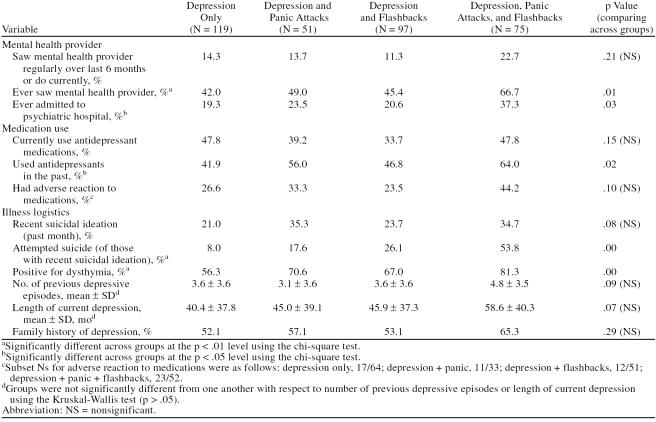

Table 3 shows the illness history by groups. The groups with comorbid anxiety symptoms tended to have more evidence of a chronic or recurrent history of mental illness. Analysis of variance across these groups showed significant differences for the percentage ever seen by a mental health provider (p < .01), the percentage ever admitted to a psychiatric hospital (p < .05), the percentage who had used antidepressants in the past (p < .05), the percentage who had attempted suicide in the past (p < .01), and the percentage found positive for dysthymia (p < .01). The differences approached significance for the percentage of those with recent suicidal ideation (p = .08), length of current depressive episode (p = .07), and number of previous depressive episodes (p = .09). Within these groups, the depression group had the lowest percentage and the depression, panic attack, and flashback group had the highest percentage of subjects with a clinically significant mental health history. The depression and panic attack and the depression and flashback groups had an intermediate percentage of subjects with significant mental health histories. Alcohol use as measured by the CAGE was not significantly different across these groups (data not shown).

Table 3.

Illness History at Baseline by Group in Patients With Depression

Regression Analysis

Multivariate linear regression models were used to assess the independent predictive capacity of the panic attack and flashback symptoms on health status and depressive symptoms. For the SF-36 PCS, the interaction between those reporting the panic attack symptom and those reporting the flashback symptom was not statistically significant (p = .24). The additive regression model estimates that subjects reporting panic attacks scored a mean of 0.027 points lower on the PCS than subjects who did not report panic attacks. Subjects reporting the flashback symptom scored a statistically significant 2.47 points lower (p < .05) than subjects who did not report the flashback symptom. Therefore, after adjusting for demographic characteristics and chronic disease score, the reporting of the flashback symptom was predictive of a lower PCS while reporting of panic attacks was not associated with PCS.

For the SF-36 MCS, the interaction between reporting the panic symptom and reporting the flashback symptom was found not to be significant (p = .30). The additive regression model estimates that subjects reporting panic attacks scored a mean of 5.36 points lower on the MCS than subjects who did not report panic (p < .01) and subjects reporting the flashback symptom scored 2.04 points lower than subjects who did not report the flashback symptom (p > .05). Therefore, we found a clinically and statistically significant association between self-reported panic attacks and MCS score; although we found that those subjects reporting the flashback symptom also tended to score lower on the MCS than those without the flashback symptoms, the difference was not statistically significant. This nonsignificant finding may be related to the fact that the flashback symptom is a weaker probe for significant anxiety.

Regression analysis results for Sheehan and SCL-20 parallel the results found for MCS. For both Sheehan and SCL-20, the interaction between self-reported panic and flashbacks was not statistically significant. In additive models, we found that subjects who reported panic scored 0.823 points higher on Sheehan (p < .01) and 0.347 points higher on SCL-20 (p < .01) than subjects who did not report panic. Although subjects who reported flashbacks tended to have higher Sheehan and SCL-20 scores than subjects who did not, the differences were not statistically significant. Thus, after adjustment for baseline demographic characteristics and CDS, self-reported panic was independently predictive of impairment on the Sheehan and severity of depression on the SCL-20 while the reporting of flashbacks was not significantly associated with either outcome.

The results of the regression analysis were consistent. Among the self-reported symptoms, the largest impact on mental health outcomes was associated with the panic attack symptom. The contribution of the flashback symptom to the outcomes was present but minimal. The combination of the 2 symptoms was additive and explained the deficit found in the depression, panic attack, and flashback group. In other words, having both symptoms did not create a level of dysfunction different from that which can be explained by each symptom individually.

DISCUSSION

In a population of VA primary care patients, we found that those with depression, panic attacks, and flashbacks as compared with those that suffered from depression alone were more likely to be younger, unmarried, and female. The groups with these comorbid symptoms also had significantly more severe depressive symptoms, significantly more impaired health status, worse disability, and a more complicated and persistent history of mental illness. Regression analysis revealed that the greatest impact on these outcomes was associated with panic attacks. Though the impact associated with flashbacks was minimal, it was additive to that caused by panic attacks. The minimal contribution made by flashbacks may be due to the fact that the flashback question is a weaker probe for significant anxiety. We believe this study is one of the first to report that a potentially more severely depressed, disabled subpopulation of depressed primary care patients can be identified by inquiring about an additional 2 comorbid anxiety symptoms.

Our findings are similar to those of other studies that have evaluated depressed patients with comorbid anxiety disorders. Those studies differ in that they employed more intensive patient evaluations.7,10,12,14,15,18,20 For example, using the Diagnostic Interview Schedule, Gaynes et al.15 found that primary care patients diagnosed with a depressive disorder and a comorbid anxiety disorder had more persistent severe depression with a greater degree of disability and health service utilization. We also found that patients with depression, panic attacks, and flashbacks were more likely to have previously seen a mental health provider, been admitted to a psychiatric hospital, met criteria for dysthymic disorder, and used antidepressant medication than those patients with depression alone.

Our results are also consistent with those of other authors who have reported that, in depressed primary care patients, a comorbid anxiety disorder has a negative impact on the course of depression.14,16,19,34 In our study, the higher rate of suicide attempts identified in patients with depression, panic attacks, and flashbacks is also consistent with other reports that those with depression and a comorbid anxiety disorder have higher rates of suicide attempts.10,20,35 We also found that the group of patients with depression without comorbid anxiety symptoms had significantly better health status as measured by the Sheehan functional status measure and the mental health subscale of the SF-36.

Due to design limitations, we were not able to determine if patients with panic attacks and/or flashbacks met full criteria for comorbid panic disorder or PTSD. Though these diagnoses may be important for treatment purposes, the first important step is to recognize patients who might be significantly impaired and require more intensive evaluation and treatment. A patient may not need to meet full criteria for these comorbid anxiety disorders to be significantly impaired. Previous work on subsyndromal depressive and anxiety disorders in primary care has shown that patients with subsyndromal disorders can be quite impaired.17,18,36 For example, there are reports that panic attacks alone that do not meet full criteria for panic disorder can cause significant impairment similar to our findings. Olfson et al.18 reported that in a population of primary care patients, those with subsyndromal depressive symptoms and to a lesser extent those with panic attacks were more disabled than those without psychiatric symptoms. Coryell et al.20 reported that a sample of depressed patients with comorbid obsessions and compulsions were more impaired compared with those with depression alone. Katon et al.37 studied a large primary care population with regards to panic disorder and panic attacks. They found that a large subgroup of patients who did not meet full criteria for panic disorder but did suffer from panic attacks had worse scores on psychological tests, more simple phobias, and a higher lifetime risk of affective illness compared with those who did not report panic attacks.37

Our results are consistent with the results of those who have studied depressed patients with comorbid anxiety disorders and those who have reported on impairment associated with subsyndromal disorders. We believe that our findings can be useful to the busy primary care provider. By asking patients with depression these 2 questions about comorbid anxiety, the primary care provider maybe able to better identify the significant comorbid anxiety disorders in patients with depression.

There are several limitations to this study. This population of patients was from a single VA primary care clinic, and the results may not generalize to other patient populations. The 2 questions used to identify subjects with comorbid anxiety were not validated as a formal screening tool for anxiety disorders. These 2 questions were asked as part of a larger questionnaire used to assess depression, and as screening questions, they may not work as well if used alone. These 2 questions are nonspecific for any unique type of anxiety disorder. Subjects who answered yes to these questions may have been suffering from other mental health conditions such as those with psychotic features. However, subjects who were acutely suicidal or whose PTSD required primary treatment were excluded from the Effectiveness of Team Treatment of Depression in VA Primary Care trial.21 Subjects who answered yes when asked if they had flashbacks or panic attacks were not subsequently evaluated for PTSD or panic disorder. As a result, we were unable to make conclusions about the best treatment approaches or likelihood of responding to treatment for these patients with depression and comorbid anxiety symptoms.

CONCLUSION

We found that when 2 questions about comorbid anxiety symptoms were used as part of a larger questionnaire for depression, we could identify a subpopulation of primary care patients with depression and comorbid anxiety symptoms who were significantly more impaired than a subpopulation of patients with depression but without comorbid anxiety symptoms. This population of patients with depression and comorbid anxiety symptoms had significantly worse depressive symptoms, mental health histories, disability, and health status than those patients with depression alone. By asking about these 2 symptoms, primary care providers evaluating depressed patients may be able to identify a group of patients who might benefit from vigorous monitoring, more aggressive therapy, and possibly collaboration with or referral to a mental health specialist.

Footnotes

The Department of Veterans Affairs, Veterans Health Administration, Health Services Research and Development Service, Washington, D.C., supported this research.

This report presents the findings and conclusions of the authors. It does not necessarily represent those of the Department of Veterans Affairs or the Health Services Research and Development Service.

REFERENCES

- Katon W, Schulberg H. Epidemiology of depression in primary care. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 1992;14:237–247. doi: 10.1016/0163-8343(92)90094-q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barsky AJ, Delamater BA, Orav JE. Panic disorder patients and their medical care. Psychosomatics. 1999;40:50–56. doi: 10.1016/S0033-3182(99)71271-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stein MB, McQuaid JR, and Pedrelli P. et al. Posttraumatic stress disorder in the primary care medical setting. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2000 22:261–269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katon W, Von Korff M, and Lin E. et al. Collaborative management to achieve treatment guidelines: impact on depression in primary care. JAMA. 1995 273:1026–1031. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Craske MG, Roy-Byrne P, and Stein MB. et al. Treating panic disorder in primary care: a collaborative care intervention. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2002 24:148–155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Veterans Health Initiative. Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder: Implications for Primary Care. Washington, DC: Department of Veterans Affairs Employee Education System. 2002 [Google Scholar]

- Sherbourne CD, Wells KB, and Meredith LS. et al. Comorbid anxiety disorder and the functioning and well-being of chronically ill patients of general medical providers. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1996 53:889–895. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gorman JM. Comorbid depression and anxiety spectrum disorders. Depress Anxiety. 1996;4:160–168. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1520-6394(1996)4:4<160::AID-DA2>3.0.CO;2-J. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ormel J, Von Korff M, and Van den Brink W. et al. Depression, anxiety, and social disability show synchrony of change in primary care patients. Am J Public Health. 1993 83:385–390. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vollrath M, Angst J. Outcome of panic and depression in a seven-year follow-up: results of the Zurich study. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 1989;80:591–596. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.1989.tb03031.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joffe RT, Bagby RM, Levitt A. Anxious and nonanxious depression. Am J Psychiatry. 1993;150:1257–1258. doi: 10.1176/ajp.150.8.1257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wittchen H-U, Lieb R, and Wunderlich U. et al. Comorbidity in primary care: presentation and consequences. J Clin Psychiatry. 1999 60suppl 7. 29–36. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sherbourne CD, Jackson CA, and Meredith LS. et al. Prevalence of comorbid anxiety disorders in primary care outpatients. Arch Fam Med. 1996 5:27–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zung WWK, Magruder-Habib K, and Velez R. et al. The comorbidity of anxiety and depression in general medical patients: a longitudinal study. J Clin Psychiatry. 1990 51(6, suppl):77–80. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaynes BN, Magruder KM, and Burns BJ. et al. Does a coexisting anxiety disorder predict persistence of depressive illness in primary care patients with major depression? [see comments]. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 1999 21:158–167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin EHB, Katon WJ, and VonKorff M. et al. Relapse of depression in primary care: rate and clinical predictors. Arch Fam Med. 1998 7:443–449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liebowitz MR. Depression with anxiety and atypical depression. J Clin Psychiatry. 1993;54(2, suppl):10–14. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olfson M, Broadhead WE, and Weissman MM. et al. Subthreshold psychiatric symptoms in a primary care group practice. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1996 53:880–886. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katon W, Roy-Byrne PP. Mixed anxiety and depression. J Abnorm Psychol. 1991;100:337–345. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.100.3.337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coryell W, Endicott J, Winokur G. Anxiety syndromes as epiphenomena of primary major depression: outcome and familial psychopathology. Am J Psychiatry. 1992;149:100–107. doi: 10.1176/ajp.149.1.100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hedrick SC, Chaney EF, and Felker B. et al. Effectiveness of collaborative care depression treatment in VA primary care. Gerontologist. In press. [Google Scholar]

- Spitzer RL, Kroenke K, and Williams JBW. and the Patient Health Questionnaire Primary Care Study Group. Validation and utility of a self-report version of PRIME-MD: the PHQ primary care study. JAMA. 1999 282:1737–1744. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- First MB, Spitzer RL, and Gibbon M. et al. Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV. New York, NY: Biometric Research, New York State Psychiatric Institute. 1995 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Samet JH, Rollnick S, Barnes H. Beyond CAGE: a brief clinical approach after detection of substance abuse. Arch Intern Med. 1996;156:2287–2293. doi: 10.1001/archinte.156.20.2287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simon GE, Revicki D, VonKorff M. Telephone assessment of depression severity. J Psychiatr Res. 1993;27:247–252. doi: 10.1016/0022-3956(93)90035-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition. Washington DC: American Psychiatric Association. 1994 [Google Scholar]

- Derogatis LR, Lipman RS, and Rickels K. et al. The Hopkins Symptom Checklist (HSCL): a measure of primary symptom dimensions. In: Pichot P, ed. Psychological Measurements in Psychopharmacology: Modern Problems in Pharmacopsychiatry, vol 7. Basel, Switzerland: Karger. 1974 79–110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kazis LE, Ren XS, and Lee A. et al. Health status in VA patients: results from the Veterans Health Study. Am J Med Qual. 1999 14:28–38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kazis LE. The Veterans SF-36 Health Status Questionnaire: developments and application in the Veterans Health Administration. Med Outcomes Trust Monitor. 2000;5:1–14. [Google Scholar]

- Lin EH, VonKorff M, and Russo J. et al. Can depression treatment in primary care reduce disability? a stepped care approach. Arch Fam Med. 2000 9:1052–1058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malone DC, Billups SJ, and Valuck RJ. et al. Development of a chronic disease indicator score using a Veterans Affairs Medical Center medication database. IMPROVE Investigators. J Clin Epidemiol. 1999 52:551–557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- VonKorff M, Wagner EH, Saunders K. A chronic disease score from automated pharmacy data. J Clin Epidemiol. 1992;45:197–203. doi: 10.1016/0895-4356(92)90016-g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mulrow CD, Williams JW Jr, and Gerety MB. et al. Case-finding instruments for depression in primary care settings. Ann Intern Med. 1995 122:913–921. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirschfeld RMA. Panic disorder: diagnosis, epidemiology, and clinical course. J Clin Psychiatry. 1996 57suppl 10. 3–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weissman MM, Klerman GL, and Markowitz JS. et al. Suicidal ideation and suicide attempts in panic disorder and attacks. N Engl J Med. 1989 321:1209–1214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wittchen H-U, Essau CA, and Krieg J-C. Anxiety disorders: similarities and differences of comorbidity in treated and untreated groups. Br J Psychiatry. 1991 159suppl 12. 23–33. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katon W, Vitaliano PP, and Anderson K. et al. Panic disorder: residual symptoms after the acute attacks abate. Compr Psychiatry. 1987 28:151–158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]