Abstract

Background:

Covert hepatic encephalopathy (CHE), which impairs health-related quality of life(HRQOL), is difficult to diagnose using currently by non-specialists. The detection rates could potentially improve with patient-administered methods that do not require specialized testing/equipment.

Aim:

To detect CHE using using demographics and a validated QOL questionnaire, Sickness Impact Profile(SIP) longitudinally.

Methods:

170 cirrhotics (55yrs, MELD 9, 50%HCV, 11%alcohol) without prior overt HE were administered cognitive tests for CHE diagnosis with SIP at baseline, six/twelve month follow-up. SIP consists of 136 questions across 12 QOL domains that require a yes/no answer over the past day. Proportion of patients that responded “yes” to each question was compared between CHE and no-CHE groups. Variables independent of cognitive testing; demographics (age, education, gender, alcoholic etiology) and SIP questions differentiating between groups were analyzed using logistic regression and ROC analysis for CHE diagnosis at baseline and six/twelve month follow-up.

Results:

93(55%) patients had CHE at baseline and on SIP, a “yes” response was found in a higher proportion of CHE patients on 54 questions across all domains. A formula to predict CHE was devised using age, male sex and four SIP questions that emerged on multi-variable analysis and ROC (SIP CHE score). A SIP CHE score>−0.079 was diagnostic of CHE with 80% sensitivity and 79% specificity at baseline. 98 patients returned at 6-months of 50% had CHE while 50 patients returned at 12-months, 32% of whom had CHE. SIP CHE score’s sensitivity at 6 months was 88% while at 12-months it was 81% for CHE diagnosis.

Conclusions:

The SIP CHE score consisting of age, gender and four SIP questions had >80% sensitivity to screen for CHE at baseline and over a 12-month follow-up period in cirrhotic patients. Patient-administered CHE screening strategies that do not include specialized testing could increase detection rates and therapy.

Keywords: minimal hepatic encephalopathy, health-related quality of life, psychometric tests, cognition, sickness impact profile, cirrhosis

INTRODUCTION

Covert hepatic encephalopathy (CHE) is a highly prevalent cognitive disorder which severely impacts health-related quality of life (HRQOL)(1). It is associated with deficits in driving and working capacity and can predict overt HE (2). However, despite these issues it is difficult to diagnose CHE because standard cognitive testing is often outside clinical practice(3). Therefore CHE patients, whose HRQOL could potentially improve post-treatment, are not diagnosed and therefore not treated(4). HRQOL questionnaires have been used to study daily function and even prognosis in cirrhosis(5, 6). The validated Sickness Impact Profile (SIP) has been used to determine patients’ daily functioning and to diagnose CHE in a prior cross-sectional study(7, 8). Our aim was to rapidly screen patients for CHE and simultaneously acquire information regarding their HRQOL using a self-administered questionnaire that does not require specialized testing in a cohort of outpatient cirrhotic patients who were then followed longitudinally over 12 months.

PATIENTS AND METHODS

Subjects

We prospectively recruited cirrhotic patients from the outpatient liver clinics at Virginia Commonwealth University Medical Center between August 2008 and February 2012 after written informed consent. All included patients had cirrhosis proven by biopsy, or endoscopic/radiological evidence of varices, thrombocytopenia and reversed liver function test ratio in patients with chronic liver disease, were able to understand English and were not on psychoactive medications apart from chronic antidepressants. We excluded patients with alcohol or illicit drug use within the last 6 months, those with current or prior overt HE or other end-stage organ failures.

We collected demographics, cirrhosis details (etiology, MELD score), and performed a recommended battery of cognitive tests [number connection test-A/B (NCT-A/B), digit symbol (DST) and block design (BDT)](9). Impairment on ≥2 tests compared to our population healthy controls was considered CHE. We also administered the validated SIP questionnaire to assess HRQOL. The questionnaire consists of 136 items grouped into 12 scales: sleep and rest, eating, work, home management, recreation and pastimes, ambulation, mobility, body care and movement, social interaction, alertness, emotional behavior, and communication. Subjects are asked to mark only those questions which are pertinent to their health over the past 24 hours. This questionnaire requires minimal explanation without physician involvement and can usually be completed within 5-20 minutes. The number of questions are weighted and divided from a total number to achieve a percentage which translates into the traditional HRQOL measure. However, we also studied the differences in marking the individual questions (yes/no) instead of the relative percentage used for HRQOL. The percentage of patients with a positive response to each of the 136 statements was compared between CHE vs. no-CHE group. Therefore we had two measures from the SIP: the traditional HRQOL measure which gives quantitative estimates and the non-traditional yes/no proportion for each question.

Six-month and 12-month follow-up

Patients enrolled for this study were followed at 6 and 12-month intervals and only those who were still eligible from the original cohort remained; the diagnosis of CHE was performed based on cognitive tests performed at that visit and the comparable diagnosis of CHE using SIP was also done based on the SIP administered during that particular visit.

Statistical analysis

The Chi-square/Fisher’s exact tests were used to assess differences in responses on the 136 SIP items between subjects with and without CHE. Statements that differed between groups (p < 0.05) where then entered into a multivariable logistic regression model along with patient characteristics [age (years), gender (male/female), race (White/African American/Hispanic/Other), education (years), cirrhosis etiology (any alcohol/no alcohol) and MELD score] using a stepwise selection procedure with a p < 0.20 significance level for entry into the model and a p < 0.05 significance level to stay in the model. A regression equation was created for the significant variables on logistic regression. Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves were created for demographic variables alone, the SIP items that were different between groups on regression alone and both together for the diagnosis of CHE. The regression equation was then applied to the patients who were followed six and twelve months later for the diagnosis of CHE.

This protocol was approved by the IRB at VCU Medical Center and all authors had access to the study data and had reviewed and approved the final manuscript.

RESULTS

At baseline, one hundred and seventy cirrhotic patients were included; 100 were men with a mean age of 55±7 years and with 14±2 years of formal education. The majority of patients had hepatitis C virus (HCV, n=86) as the etiology, followed by NASH (non-alcoholic steatohepatitis) in 34 patients, combination of alcohol and HCV in 12 patients, alcohol alone in 7 patients and other etiologies in 31 patients. The average MELD score was 9.2±3.5 indicating a largely compensated population. Using the cognitive testing, 93 (55%) of patients were diagnosed with CHE after comparing with our healthy control data(10). These CHE patients had a significantly worse HRQOL by SIP using the traditional analysis on all domains (Table 1). We found that 54 out of 136 SIP statements, from all domains but communication, were statistically different between those with CHE on simple logistic regression analysis of each of the SIP statements (Supplementary Table). The predictive power of the 54 selected statements with that of age, gender, MELD, years of education and any alcoholic etiology for the diagnosis of CHE was evaluated using the regression model (Table 2). On simple regression, MELD was a significant predictor of CHE (p = 0.031, OR=1.42,CI:1.01,1.29)). It remained significant despite addition of the other demographic variables (p=0.042, OR=1.14, CI::1.01,1.29)). However, it became non-significant once the SIP variables identified were included in the model (p=0.07, OR=1.03, CI: 0.89, 1.18)).

TABLE 1.

Baseline demographics and Health-related Quality of Life

| No Covert HE (n=77) |

Covert HE (n=93) |

P value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 53.8±6.8 | 56.0±6.6 | 0.03 |

| Gender (men/women) | 54% | 63% | 0.27 |

| Education (years) | 14.1±2.3 | 13.3±2.3 | 0.02 |

| Etiology of cirrhosis (HCV/NASH/HCV+ alcohol/Alcohol only/others) |

38/16/1/4/18 | 47/16/7/4/19 | 0.26 |

| MELD score | 8.4±2.8 | 9.8±2.9 | 0.02 |

| Ascites (all controlled on diuretics %) | 35% | 40% | 0.52 |

| On anti-depressants (SSRIs in all %) | 20% | 26% | 0.35 |

| Number connection-A (sec) | 26.4±6.1 | 43.8±17.4 | <0.0001 |

| Number connection-B (sec) | 61.5±15.8 | 127.1±79.0 | <0.0001 |

| Digit Symbol (raw score) | 71.7±14.3 | 52.5±12.7 | <0.0001 |

| Block design (raw score) | 39.8±10.4 | 21.9±12.3 | <0.0001 |

| Traditional SIP Scoring for HRQOL | |||

| SIP total score | 7.4±9.9 | 16.2±13.8 | <0.0001 |

| SIP psychosocial domain | 6.3±9.6 | 12.9±17.5 | 0.002 |

| SIP physical domain | 3.9±6.4 | 10.3±10.6 | <0.0001 |

| Independent domains | |||

| Home Management | 6.8±10.3 | 22.9±22.7 | <0.0001 |

| Sleep and Rest | 12.8±18.8 | 28.3±24.0 | <0.0001 |

| Eating | 1.7±3.5 | 5.4±8.2 | <0.0001 |

| Work | 15.6±26.5 | 32.4±31.2 | <0.0001 |

| Recreation and Pastimes | 12.1±16.3 | 23.6±22.9 | <0.0001 |

A high score on SIP using the traditional scoring indicates worse quality of life; SSRI: selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors, HRQOL: health-related quality of life.

Table 2.

Multiple variable logistic regression with covert HE as the dependent variable showing the significant variables

| Type of variables |

Factor | Estimated Parameter |

Standard Error |

p-value | OR | 95% CI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intercept | −6.0016 | 1.8150 | 0.0009 | ---- | ---- | |

| Demographics | Age | 0.0879 | 0.0312 | 0.004 | 1.09 | (1.03, 1.16) |

| Gender Male | 0.9151 | 0.4125 | 0.027 | 2.50 | (1.1, 5.6) | |

| SIP Items |

BCM4 - I do not maintain balance |

2.6322 | 1.1080 | 0.018 | 13.91 | (1.6,121.9) |

| EB7 - I act irritable or impatient with myself |

2.4295 | 0.8320 | 0.004 | 11.35 | (2.2, 57.9) | |

| RP8 - I am not doing any of my usual physical recreation or activities |

1.8688 | 0.9083 | 0.03 | 6.48 | (1.09, 38.4) | |

| E1 - I am eating much less than usual |

1.8870 | 0.6812 | 0.006 | 6.60 | (1.7, 25.1) |

Using these results, a score for predicting CHE from the following can be calculated as:

BCM 4: “I do not maintain balance”; EB7: “I act irritable or impatient with myself”; RP8: “I am not doing any of my usual physical recreation or activities” and E1: “I am eating much less than usual”. After calculating this score, if a patient has a score greater than 0 they are classified as CHE. Figure 2 exhibits how the predicted probability of CHE increases as the score from the model using both demographics and SIP questions, with a vertical reference line at the optimal cut-point. For the data at baseline, the sensitivity is 0.89 with 95% CI (0.81, 0.95) and the specificity is 0.46 with 95% CI (0.34, 0.58). The score of ≥0 for CHE was rounded off for easier diagnosis, however the original optimal cut-point for the regression equation for CHE is −0.0788; with this cut-point, the sensitivity is 0.80 while the specificity is 0.79.

Figure 2. Logistic regression curve at baseline for the SIP CHE index.

Y axis is the probability of covert HE with increasing score on the SIP CHE index consisting of four questions of the SIP and age and male gender. SIP: Sickness Impact Profile; CHE: covert hepatic encephalopathy.

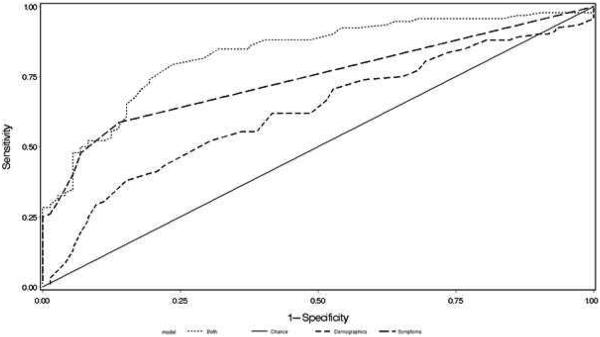

Three ROC curves were constructed (Figure 1); the first ROC curve contained used the significant demographic variables (age and male gender), the second used only the four SIP questions and the third used both the demographic and SIP variables. The area-under-the curve for the ROC was 0.67 for age and male gender only, 0.78 for the four SIP questions only and 0.87 for both.

Figure 1. Receiver operating characteristic curve for CHE diagnosis:

Using demographics (age and male gender) alone (small dashed line), the four defining questions on the Sickness Impact Profile (large dashed line) and both together (dotted lines) shows the highest area-under-the curve with both demographics and the four questions. CHE: covert hepatic encephalopathy

Six and Twelve-month follow-up

At 6 months, 98 patients returned who again fulfilled the entry criteria of the original cohort. Of the 98, 49 had CHE, of which 44 or 90% also had CHE at baseline while 5 new patients developed CHE. Of the remaining 49 patients, 40 remained CHE negative while 9 recovered spontaneously compared to baseline. At the 6-month mark CHE patients continued to be older (57.5±5.2 vs 54.5±5.3 years, p=0.006) with a non-significant trend towards higher MELD (9.3±3.6 vs. 8.2±2.3, p=0.09) and lower education (13.6±2.1 vs. 14.2±2.1 years, p=0.17). Gender ratio remained similar (54 vs 64% men, p=0.29).

At 12 months, 50 patients returned who again fulfilled the entry criteria of the original cohort. Of these 16 had CHE and 13 (81%) of these had CHE 6 months prior and 15 (94%) had CHE 12 months ago at baseline. Of the 34 without CHE, 26 (75%) were CHE negative 6 months prior and 24 (69%) were negative 12 months ago at baseline. At 12 months CHE patients were statistically similar in age (56.7±6.3 vs. 56.4±5.0, p=0.85), education (13.5±2.5 vs. 14.7±2.9, p=0.07), MELD (9.2±4.5 vs. 8.7±2.1, p=0.68) and gender ratio (62 vs. 65% men, p=0.83).

SIP CHE score: At 6 months; calculating the score using the scoring criteria above, sensitivity was 0.88 with 95% CI (0.75, 0.95) and specificity was 0.37 with 95% CI (0.23, 0.52). At 12 months, calculating the score and using the scoring criteria above, sensitivity was calculated to be 0.81 with 95% CI (0.54, 0.96) and specificity of 0.24 with 95% CI (0.11. 0.41).

DISCUSSION

While there is increasing consensus that covert HE is an important issue in cirrhosis, there is little agreement regarding testing strategies(11). As a result, the majority of potential CHE patients is not diagnosed and therefore not offered treatment that could potentially improve their outcomes, especially HRQOL. The use of a self-administered questionnaire that gives information regarding HRQOL as well as CHE diagnosis is therefore a useful investigative method. Several studies have utilized the SIP in patients with cirrhosis and cognitive dysfunction and have demonstrated its responsiveness to underlying change in the patients’ conditions(4, 12, 13). Although it is a general and not a liver-specific questionnaire, the large breadth of its questions and inquiry of symptoms over the last 24 hours are particularly relevant to as an exploratory tool for the diagnosis of CHE. As expected, we found on an aggregate, a significantly worse total SIP, psychosocial and physical dimensions of the SIP in CHE patients. However the continuous score on the traditional HRQOL use of the SIP cannot differentiate between CHE and no-CHE patients. Interestingly, of the 136 questions, only 54 items were significantly different between CHE and no-CHE groups. These questions spanned several dimensions indicating the widespread effect of CHE on HRQOL in cirrhosis. Similar to prior studies, none of the “communication” questions were different between patients with and without CHE(4).

On multiple variable analysis, these 54 questions were reduced to four specific questions belonging to four dimensions: body care and mobility, emotional behavior, recreation and pastimes and eating. The question on body care and mobility confirms prior studies pertaining to falls and balance in prior CHE studies (14). The next question pertaining to not doing their usual physical recreation and activities builds on the difficulties in continuing daily life in the setting of CHE given the slowed psychomotor speed, response time, visuo-motor coordination and fatigue(8, 15, 16). Acting irritable and impatient with oneself and not eating enough, two features of major depression, were the remaining two questions. This is reflective of the underlying mood issues that may be under-diagnosed in this population and likely would not have reached the level of therapeutic necessity given anti-depressant use was similar across CHE and no-CHE groups(17). The eating question is interesting in that although malnutrition is extensively described in advanced cirrhosis, the emergence of this observation in this relatively compensated population could herald further decompensation(18). The groups were compensated with similar rates of controlled ascites so it is unlikely that ascites per se could be implicated.

The discriminating ability of these four questions was increased if the patients were older or men. Prior studies have shown a greater prevalence of CHE and worse HRQOL in older cirrhotic patients, which could reflect super-added mild cognitive impairment and other co-morbidities(8). However we reduced this possibility by excluding patients above 65 years or on psychoactive medications. The contribution of gender is intriguing since at least in one CHE study, men reacted faster than women; it is possible that the loss of this reactive ability could have triggered a greater health-related introspection in men (19). Male gender was also found to be important with five SIP questions, varices and Child score, by Groeneweg et al in defining CHE using a different gold standard that included EEG, digit symbol and number connection-A tests(8). We used MELD score, which did not discriminate between groups, instead of Child score because the inclusion of the subjective HE and ascites in that particular system. Their CHE rate was 37% compared to our 55% which may reflect differing underlying patho-physiological changes in those with abnormal EEG compared with those with abnormal paper-pencil tests(20). While studies providing an overview of interaction between HRQOL and cognition including CHE differ in their demographics, methods for CHE diagnosis and HRQOL assessment, they consistently identify three domains; cognitive impairment, neuromuscular integration deficits, and emotional disturbance, in affected patients. Nardelli et al. emphasize depression as the major HRQOL determinant(21). Schomerus et al noted aggressiveness and depression are the dominant determinants of lifestyle disruption(22), while Groeneweg et al., note that cognitive dysfunction i.e. confusion and memory impairment, and fatigue are the define CHE using HRQOL measures(8, 16). As in prior studies, we found neuromuscular (age, inability to maintain balance), emotional (irritability, decrease in appetite) and fatigue (inability to perform usual activities) as discriminating elements between affected and unaffected patients as defining features of CHE. Our results extend these to longitudinal follow-up of these patients and show that these non-specialized results remain relatively stable in CHE detection paralleling standard tests. This also reflects a growing trend of using patient-reported outcomes to focus care while keeping the patients engaged in the process(17, 23).

While the use of cognitive batteries and neurophysiological tests will remain the gold standard for CHE diagnosis, these tests are not easy to administer in clinics. The advantages of SIP are its limited cognitive demands on the subject or administrators, broad spectrum of questions, no need for specific expertise and ability to be performed at the subjects’ pace. It can also be administered telephonically the day prior to clinic by clinic staff since the results are valid for 24 hours (7).The results could screen for both patients who may have CHE or those who do not require future testing given the high sensitivity and specificity at baseline. These results could also be considered diagnostic of CHE if the clinicians do not have access to gold-standard testing expertise.

Our study is potentially limited by the need to use the entire SIP instrument since our sample size did not allow for further individual question group-based multi-variable testing. However this provides us a valuable HRQOL instrument that may also increase the subjects’ insight into their issues and enhance their receptiveness for CHE or symptom-specific treatment.

The use of patient-reported outcomes could be unstable given that the SIP only reflects the patient’s personal observation over the last 24 hours and accurate answers may depend on insight, cultural factors and willingness to share information. Therefore, we studied the cohort at 6 and 12 months and found that the SIP was stably representative of the patients’ CHE status. However, like any other patient-reported survey or cognitive testing, these instruments are sensitive but not specific and therefore can be influenced by any condition that could affect the patient’s interpretation of their overall functioning. Also HRQOL impairment is not uniform in all CHE studies, therefore these findings need to be further validated, especially after treatment of CHE(24).

We conclude that the SIP CHE score can screen for covert HE in an outpatient population of compensated cirrhotic patients while also giving important information regarding the underlying HRQOL in these patients. The SIP CHE score was also able to diagnose CHE with good accuracy in the longitudinal follow-up of these patients. Screening strategies for CHE are needed to encourage diagnosis and ultimate therapy and validation of the use of SIP for CHE is needed in other populations.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Grant Support: This work was partly supported by grant RO1AA020203 from the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism, grant RO1DK087913 from the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases, grant UL1TR00058 from the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences and the American College of Gastroenterology Junior Faculty Development Award.

Abbreviations

- CHE:

covert hepatic encephalopathy

- SIP:

- sickness impact profile, SIP subcategories

- SR:

- sleep and rest

- EB:

- emotional behavior

- BCM:

- body care and movement

- HM:

- household management

- M:

- mobility

- SI:

- social interaction

- A:

- ambulation

- AB:

- alertness behavior

- C:

- communication

- W:

- work

- RP:

- recreation and pastimes

- E:

- eating

- ROC:

receiver operating characteristic

- HRQOL:

health-related quality of life

- NCT-A/B:

number connection test-A/B

- DST:

digit symbol test

- BDT:

block design test

- HCV:

hepatitis C virus

- NASH:

non-alcoholic steatohepatitis

- SSRI:

selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Disclosures: No relevant disclosures

Writing Assistance: No writing assistance

Author Contributions: JSB was involved in all aspects, LRT and EN were involved in data analysis, EN, RKS, RTS, MF, DMH, IB, AJS, MSS, VL, MBW, PM, NAN and AU helped in patient recruitment and data collection, JBW helped in analysis and critical revisions in the manuscript.

References

- 1.Kappus MR, Bajaj JS. Covert hepatic encephalopathy: not as minimal as you might think. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2012;10:1208–1219. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2012.05.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ortiz M, Jacas C, Cordoba J. Minimal hepatic encephalopathy: diagnosis, clinical significance and recommendations. J Hepatol. 2005;42:S45–53. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2004.11.028. Suppl. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bajaj JS, Etemadian A, Hafeezullah M, Saeian K. Testing for minimal hepatic encephalopathy in the United States: An AASLD survey. Hepatology. 2007;45:833–834. doi: 10.1002/hep.21515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Prasad S, Dhiman RK, Duseja A, Chawla YK, Sharma A, Agarwal R. Lactulose improves cognitive functions and health-related quality of life in patients with cirrhosis who have minimal hepatic encephalopathy. Hepatology. 2007;45:549–559. doi: 10.1002/hep.21533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kanwal F, Gralnek IM, Hays RD, Zeringue A, Durazo F, Han SB, Saab S, et al. Health-related quality of life predicts mortality in patients with advanced chronic liver disease. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2009;7:793–799. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2009.03.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Younossi ZM, Guyatt G, Kiwi M, Boparai N, King D. Development of a disease specific questionnaire to measure health related quality of life in patients with chronic liver disease. Gut. 1999;45:295–300. doi: 10.1136/gut.45.2.295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bergner M, Bobbitt RA, Carter WB, Gilson BS. The Sickness Impact Profile: development and final revision of a health status measure. Med Care. 1981;19:787–805. doi: 10.1097/00005650-198108000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Groeneweg M, Moerland W, Quero JC, Hop WC, Krabbe PF, Schalm SW. Screening of subclinical hepatic encephalopathy. J Hepatol. 2000;32:748–753. doi: 10.1016/s0168-8278(00)80243-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ferenci P, Lockwood A, Mullen K, Tarter R, Weissenborn K, Blei AT. Hepatic encephalopathy--definition, nomenclature, diagnosis, and quantification: final report of the working party at the 11th World Congresses of Gastroenterology, Vienna, 1998. Hepatology. 2002;35:716–721. doi: 10.1053/jhep.2002.31250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bajaj JS, Thacker LR, Heuman DM, Fuchs M, Sterling RK, Sanyal AJ, Puri P, et al. The Stroop smartphone application is a short and valid method to screen for minimal hepatic encephalopathy. Hepatology. 2013 doi: 10.1002/hep.26309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bajaj JS, Cordoba J, Mullen KD, Amodio P, Shawcross DL, Butterworth RF, Morgan MY. Review article: the design of clinical trials in hepatic encephalopathy--an International Society for Hepatic Encephalopathy and Nitrogen Metabolism (ISHEN) consensus statement. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2011;33:739–747. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2011.04590.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sidhu SS, Goyal O, Mishra BP, Sood A, Chhina RS, Soni RK. Rifaximin improves psychometric performance and health-related quality of life in patients with minimal hepatic encephalopathy (the RIME Trial) Am J Gastroenterol. 2011;106:307–316. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2010.455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bajaj JS, Heuman DM, Wade JB, Gibson DP, Saeian K, Wegelin JA, Hafeezullah M, et al. Rifaximin improves driving simulator performance in a randomized trial of patients with minimal hepatic encephalopathy. Gastroenterology. 2011;140:478–487. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2010.08.061. e471. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Soriano G, Roman E, Cordoba J, Torrens M, Poca M, Torras X, Villanueva C, et al. Cognitive dysfunction in cirrhosis is associated with falls: a prospective study. Hepatology. 2012;55:1922–1930. doi: 10.1002/hep.25554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Weissenborn K, Ennen JC, Schomerus H, Ruckert N, Hecker H. Neuropsychological characterization of hepatic encephalopathy. J Hepatol. 2001;34:768–773. doi: 10.1016/s0168-8278(01)00026-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bajaj JS, Hafeezullah M, Zadvornova Y, Martin E, Schubert CM, Gibson DP, Hoffmann RG, et al. The effect of fatigue on driving skills in patients with hepatic encephalopathy. Am J Gastroenterol. 2009;104:898–905. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2009.7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bajaj JS, Thacker LR, Wade JB, Sanyal AJ, Heuman DM, Sterling RK, Gibson DP, et al. PROMIS computerised adaptive tests are dynamic instruments to measure health-related quality of life in patients with cirrhosis. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2011;34:1123–1132. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2011.04842.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Amodio P, Bemeur C, Butterworth R, Cordoba J, Kato A, Montagnese S, Uribe M, et al. The nutritional management of hepatic encephalopathy in patients with cirrhosis: International Society for Hepatic Encephalopathy and Nitrogen Metabolism Consensus. Hepatology. 2013;58:325–336. doi: 10.1002/hep.26370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lauridsen MM, Gronbaek H, Naeser EB, Leth ST, Vilstrup H. Gender and age effects on the continuous reaction times method in volunteers and patients with cirrhosis. Metab Brain Dis. 2012;27:559–565. doi: 10.1007/s11011-012-9318-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Montagnese S, Biancardi A, Schiff S, Carraro P, Carla V, Mannaioni G, Moroni F, et al. Different biochemical correlates for different neuropsychiatric abnormalities in patients with cirrhosis. Hepatology. 2011;53:558–566. doi: 10.1002/hep.24043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nardelli S, Pentassuglio I, Pasquale C, Ridola L, Moscucci F, Merli M, Mina C, et al. Depression, anxiety and alexithymia symptoms are major determinants of health related quality of life (HRQoL) in cirrhotic patients. Metab Brain Dis. 2013;28:239–243. doi: 10.1007/s11011-012-9364-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Schomerus H, Hamster W. Quality of life in cirrhotics with minimal hepatic encephalopathy. Metab Brain Dis. 2001;16:37–41. doi: 10.1023/a:1011610427843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mellinger JL, Volk ML. Multidisciplinary management of patients with cirrhosis: a need for care coordination. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2012;11:217–223. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2012.10.040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wunsch E, Szymanik B, Post M, Marlicz W, Mydlowska M, Milkiewicz P. Minimal hepatic encephalopathy does not impair health-related quality of life in patients with cirrhosis: a prospective study. Liver Int. 2011;31:980–984. doi: 10.1111/j.1478-3231.2011.02465.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.