Abstract

Many tumors contain mutations that confer defects in the DNA-damage response and genome stability. DNA-damaging agents are powerful therapeutic tools that can differentially kill cells with an impaired DNA-damage response. The response to DNA damage is complex and composed of a network of coordinated pathways, often with a degree of redundancy. Tumor-specific somatic mutations in DNA-damage response genes could be exploited by inhibiting the function of a second gene product to increase the sensitivity of tumor cells to a sublethal concentration of a DNA-damaging therapeutic agent, resulting in a class of conditional synthetic lethality we call synthetic cytotoxicity. We used the Saccharomyces cerevisiae nonessential gene-deletion collection to screen for synthetic cytotoxic interactions with camptothecin, a topoisomerase I inhibitor, and a null mutation in TEL1, the S. cerevisiae ortholog of the mammalian tumor-suppressor gene, ATM. We found and validated 14 synthetic cytotoxic interactions that define at least five epistasis groups. One class of synthetic cytotoxic interaction was due to telomere defects. We also found that at least one synthetic cytotoxic interaction was conserved in Caenorhabditis elegans. We have demonstrated that synthetic cytotoxicity could be a useful strategy for expanding the sensitivity of certain tumors to DNA-damaging therapeutics.

Keywords: synthetic cytotoxicity, genetic interaction, DNA damage response, conditional synthetic lethality, DNA-damaging agents

CHANGES in genome structure and sequence underlie oncogenesis (Charames and Bapat 2003; Schvartzman et al. 2010). These tumor-specific somatic mutations can be exploited to target tumor cells for killing relative to normal cells (Hartwell et al. 1997). Genome stability genes, such as TP53, ATM, BRCA1, BRCA2, and MSH2, are frequently mutated in tumors and many current antitumor therapeutics exploit genome stability defects through the use of DNA-damaging genotoxic agents (Helleday et al. 2008). The resultant DNA-damage results in cell-cycle arrest and cell death. However, DNA-damaging therapeutic agents often have a low therapeutic index relative to toxicity and can cause deleterious side effects and generate new mutations that can result in therapeutic resistance or secondary cancers.

Over a decade ago, two important concepts were proposed to facilitate the development of new anticancer drugs. First, that the somatic mutations in cancers could selectively sensitize tumor cells to therapies that inhibit the function of a second gene product resulting in synthetic lethality (SL). Second, that SL interactions, which are defined between two genes when disruption of function of either gene product is viable but disruption of function of both simultaneously results in death, could be screened in genetically amenable model organisms to identify those that may be relevant to the treatment of tumors (Hartwell et al. 1997).

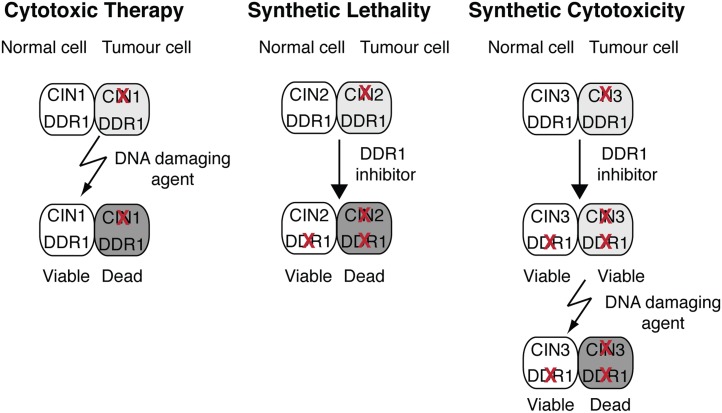

Not all tumors contain mutations that can be exploited by treatment with DNA-damaging agents (because, for example, of redundancy in the DNA-damage response), or by synthetic lethal approaches (because, for example, SL partners do not exist or the SL partners are not “druggable” targets). It is possible that these tumors could be sensitive to a combination of the two approaches. In a manner similar to a SL interaction, a somatic tumor-specific mutation together with inhibition of a second gene product could increase the sensitivity of tumor cells to a low, sublethal concentration of DNA-damaging agent resulting in a conditional synthetic lethality that we are calling synthetic cytotoxicity (SC) (Figure 1). For instance, cells with mutations affecting a DNA-damage repair pathway may rely on parallel or adapted DNA-repair pathways when treated with DNA-damaging agents (Bandyopadhyay et al. 2010; Guenole et al. 2013). Hence, modulation of DNA-damage responses genetically with mutations or chemically with small molecule inhibitors of DNA-repair enzymes could selectively enhance the sensitivity of cancer cells to DNA-damaging therapies resulting in SC.

Figure 1.

Schematic of cytotoxic therapy, synthetic lethality, and synthetic cytotoxicity. Selective killing of tumor cells using DNA-damaging therapeutic agents and DNA-repair enzyme inhibitors. Cytotoxic therapy: A mutation in the chromosome stability gene CIN1 sensitizes tumor cells to DNA-damaging agents. Unrepaired induced DNA damage leads to cell death. Synthetic lethality: A mutation in CIN2 is synthetic lethal with inhibition of DDR1, a DNA-damage response (DDR) protein. Endogenous DNA damage cannot be repaired in the absence of both CIN2 and DDR1 and leads to cell death. This outcome is analogous to the synthetic lethality observed when cells with BRCA1 or BRCA2 mutations are treated with PARP inhibitor. Synthetic cytotoxicity: Inhibition of DDR1 in the CIN3 mutant background does not result in synthetic lethality but loss of function of both proteins sensitizes the tumor cell to a low sublethal dose of DNA-damaging agent, enhancing the differential killing of tumor cells relative to a CIN3 wild-type background.

Mapping the large number of genetic interactions needed to identify SC in human cells is feasible but techniques are not as robust as those currently available in budding yeast. Synthetic genetic arrays (SGA) in yeast facilitate the collection and analysis of genetic interaction data (Tong et al. 2001; Collins et al. 2007; Costanzo et al. 2010). The use of the model organisms, yeast, and Caenorhabditis elegans, to identify conserved genetic interactions with potential cancer therapeutic value has proven effective (McLellan et al. 2012; McManus et al. 2009; van Pel et al. 2013).

As a proof of principle study of SC, we screened the Saccharomyces cerevisiae collection of nonessential gene deletions for SC interactions with the topoisomerase I poison camptothecin (CPT) and a deletion of the yeast ATM (ataxia telangiectasia mutated) ortholog, TEL1. TEL1 was chosen in our study to represent a frequently mutated tumor-associated genome stability gene. The ATM gene is mutated in the hereditary cancer-prone human disease ataxia telangiectasia (AT) (Savitsky et al. 1995). Cells from AT patients exhibit radiosensitivity, altered DNA repair, cell-cycle checkpoint defects, short telomeres, and chromosome instability (Lavin. 2008). Although AT is rare, with a frequency of ∼1/40,000, up to 1% of the population could be heterozygous carriers of ATM mutations, and these carrier individuals are estimated to have an increased risk of pancreatic cancer and breast cancer (Savitsky et al. 1995; Thompson et al. 2005; Renwick et al. 2006; Roberts et al. 2012). In addition to hereditary cancer, ATM mutations are frequently detected in diverse sporadic cancers (Stankovic et al. 2002; Gumy-Pause et al. 2004; Hall. 2005; Kang et al. 2008). Importantly for this study, the function of ATM in genome stability appears to be well conserved between in yeast, worm, and human (Fritz et al. 2000; Garcia-Muse and Boulton 2005; Jones et al. 2012).

We performed digenic SGA screens with tel1Δ as a query mutation in the presence or absence of CPT to identify common processes required for resistance to camptothecin when Tel1 is absent. We identified and validated 14 gene mutations that resulted in SC with tel1Δ and CPT. We also demonstrated that at least one SC interaction is conserved in C. elegans. This study demonstrates the utility of model organisms in screening for SC to DNA-damaging chemotherapeutics and raises the potential for detecting candidate combination therapies in simple model organisms.

Materials and Methods

Media and growth conditions

Yeast was grown in rich media at 30°. Plasmid-bearing strains were grown in synthetic complete media lacking the appropriate nutrient. All strains are BY4743 background (Brachmann et al. 1998). Single-gene knockout alleles were generated through tetrad dissection using the heterozygous gene deletion collection as starting resource (kindly provided by Jef Boeke) (Pan et al. 2004). All double-mutant heterozygous strains were then constructed by mating each of the respective single mutants. All haploid double-mutant strains were generated by sporulation of diploid heterozygous double-mutant strains followed by tetrad dissection. The genotypes of all the strains used in the experiment were checked by PCR for confirmation of the gene deletions (Supporting Information, Table S1). SML1 was deleted to maintain the viability of cells with mec1Δ (Zhao et al. 1998).

Synthetic genetic array construction and analysis

SGA analyses were performed using a Singer RoToR as described in Tong et al. (2004). The MATa yeast deletion mutant set (ykoΔ::kanMX) was arrayed at a density of 1536 colonies/plate by robotic pining. The media for SGA were the same as described in Tong et al. (2004). MATa deletion mutant array (DMA) for SGA was obtained from Research Genetics Company (http://www.sequence.stanford.edu/group/yeast_deletion_project/deletions3.html). Statistical analysis was performed in R (J. Stoepel, J. Bryan, K. Ushey, B. P. Young, C. J. Loewen, and P. Hieter, unpublished results) using a script that compares the colony size measurements for each gene pair. The program output (EC value) is a measure of the difference in colony size, a proxy for strain fitness, of corresponding colonies on the single- and double-selection plates, and a measure of statistical significance (P-value).

Plate assays and growth curve analysis

To identify SC interactions we utilized qualitative plate assays as well as quantitative growth-curve analyses comparing the agent sensitivity of double-mutant strains with the two single-mutant parental strains. Different camptothecin concentrations were used to maximize growth differences for single-, double-, and triple-mutant strains and allow for identification of additive and suppressing effects. For plate assays, cells were grown in YPD media until log phase before spotting on YPD plates and growth assessed by visual inspection. For growth-curve analysis, cells were grown in YPD media until log phase before addition to YPD liquid media containing sublethal doses of the DNA-damaging agents. Cell density was normalized by OD600 readings. For each agent, the concentration was optimized to noticeably inhibit at least one single parental mutant strain growth and further diluted 4–8× to determine the sensitivity of the double mutants compared to wild type. For plate spot assays, an identical optical density (OD600) of cells was serially diluted fivefold and spotted on the indicated plate at the indicated temperature for 72 hr. For growth-curve analysis, logarithmic phase cultures were diluted to an OD600 value of 0.15 in 96-well plates and grown for 24 hr in a TECAN M200 plate reader at 30°. Each strain was tested in three replicates. Strain fitness F was based on the area under the curve (AUC) of mutants relative to wild type as previously described (McLellan et al. 2012). Genetic interactions were quantified through the comparison of fitness of double mutants and the expected phenotype based on the two single mutants. Mutations in independent genes (two genes with a neutral interaction) often combine to generate fitness (growth relative to WT) in a multiplicative manner. The expected fitness of the resulting double mutant is assumed to be Fabexpected = Fa × Fb. The interaction can be quantitatively measured by comparing double mutant Fab against Fabexpected (Mani et al. 2008).

C. elegans brood and camptothecin assays

C. elegans strains were cultured at 20° under standard conditions. Bristol N2 was used as the wild-type strain. The following mutations were used in this study: atm-1(tm5027), rfs-1(ok1372), cku-80(tm1203), and lig-4(ok716). Hatching rates and male production were assessed by individually plating 10–20 L4 larvae of each genotype and transferring the animals every 24 hr until the onset of sterility. The number of embryos was counted immediately after transferring and the number of adult worms was counted 48 hr later. The percentage of males among adults was determined. To assess CPT sensitivity, early adults were treated with 0, 5, 10, or 20 nM CPT in M9 buffer containing E. coli OP50 for 19 hr. Fifty animals were plated 10 per plate on an OP50 seeded NGM plate and cultured to produce progeny. After 2 hr, treated P0 animals were removed. The number of inviable embryos and adults was scored 24 and 72 hr later, respectively. Percentage embryonic survival was calculated by dividing the total number of adults by the total progeny (adults + inviable embryos).

C. elegans DAPI staining

Young adult hermaphrodites were picked to a watch glass containing 10–20 μl of M9 buffer. A total of 500 μl 96% ethanol containing 0.1μg/ml DAPI was added to the watch glass and incubated at room temperature for 30 min in the dark. Fixed and stained worms were washed with 2 ml M9 buffer 3× (30 min per wash) before mounting on 1% agarose-coated microscope slide. The condensed meiotic chromosomes were visualized using a 100× objective on a Zeiss Axioplan 2 microscope.

Results

tel1Δ rad27Δ is synthetic cytotoxic to camptothecin

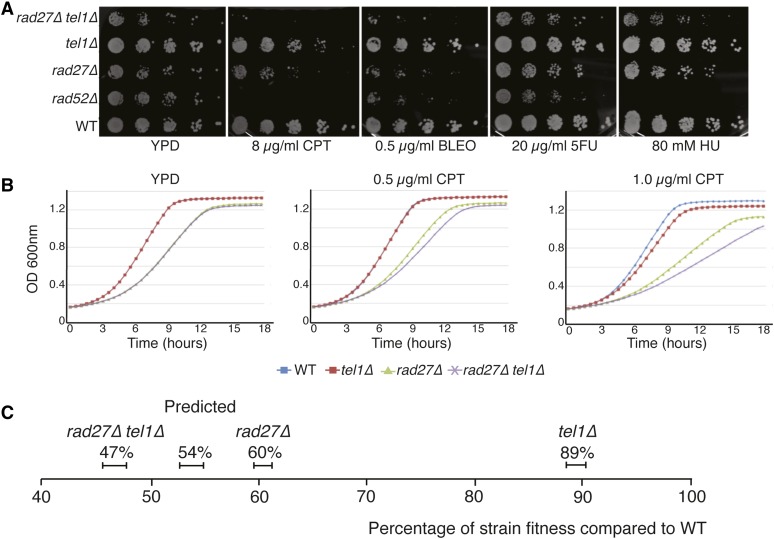

Although Tel1 plays a role in the DNA-damage response, few synthetic lethal interactions have been identified with tel1 mutants (Stark et al. 2006). We tested whether loss of a second DNA-repair gene sensitized the tel1 mutant to sublethal concentrations of DNA-damaging agents resulting in SC. The function of Tel1 partially overlaps with the related kinase Mec1 (Shiloh. 2003; Budd et al. 2005; Chakhparonian et al. 2005); therefore, we tested both tel1 and mec1 deletions for SC to DNA-damaging agents in combination with deletions in three DNA-repair enzyme genes: TDP1 (tyrosyl-DNA-phosphodiesterase 1), TPP1 (three prime phosphatase 1), and RAD27 (radiation sensitive 27). Viable double mutants were tested for SC by comparing the growth of double mutant strains to the two single mutant parental strains using a quantitative liquid growth curve assay in the presence or absence of four different DNA-damaging agents: bleomycin (BLEO), 5-fluorouracil (5FU), CPT, and hydroxyurea (HU). mec1Δ rad27Δ was synthetic lethal, which is consistent with previous reports (Pan et al. 2006). tel1Δ rad27Δ was SC to sublethal concentrations of CPT but not to other DNA-damaging agents (Figure 2A). Quantitative liquid growth-curve analysis at a range of CPT concentrations confirmed that the double-mutant growth was worse than what was predicted from a multiplicative model based on the effect on each single mutant (Figure 2, B and C).

Figure 2.

Synthetic cytotoxicity of rad27Δ tel1Δ to CPT. (A) Sensitivity to CPT of single and double mutants in spot assays. rad52Δ (positive control) and rad27Δ tel1Δ mutants are hypersensitive to CPT. tel1Δ is mildly sensitive compared to wild type, while rad27Δ shows a mild growth defect. (B) Fitness data from growth-curve assay demonstrating the synthetic cytotoxicity of rad27Δ tel1Δ to CPT. Quantitative measurement of genetic interaction between rad27Δ and tel1Δ. (C) Plot showing the analysis of growth-curve values derived from area under the curve (AUC). The expected fitness values of double mutants are obtained by multiplying two single mutant fitness values together. The actual fitness of rad27Δ tel1Δ in the presence of 1 μg/ml CPT is ∼7% lower than expected, indicating that rad27Δ tel1Δ is SC to CPT. Error bars represent standard deviation.

SC interactions with tel1Δ and CPT identified by SGA analysis

The SC of tel1Δ rad27Δ to CPT led us to screen for SC interactions with CPT and tel1Δ on a genome-wide scale. We constructed double mutants by mating a tel1Δ query strain to an ordered array of ∼4800 nonessential gene deletion mutants that represent ∼80% of all yeast genes (Tong and Boone 2006). The single- and double-deletion haploid strains were replicated onto media containing 4 µg/ml CPT (Figure S1). SC was identified when a double mutant exhibited a growth defect in the presence of CPT that was greater than that predicted using a multiplicative model based on the growth of single mutants (Figure S2).

We identified 173 double mutants that showed significant growth defects compared to single mutants (P-value <0.05), which included all potential SC/SL interaction genes as well as single mutants that are sensitive to CPT. After removing single mutants that were sensitive to CPT and five false-positive interactions that were due to linkage to the query gene TEL1, the SGA screen resulted in 22 candidates (EC < −0.4 P-value < 0.05) as potential SL/SC interactions partner genes with tel1Δ (Table 1).

Table 1. SL/SC candidate validation.

| Function | Gene | EC value | P-value | Random spore | Growth curve | Interaction |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Shu complex | CSM2 | −0.4399 | 0.004 | + | + | SC |

| PSY3 | −0.4109 | <0.001 | + | SC | ||

| SHU1 | −0.2937 | 0.136 | + | SC | ||

| SHU2 | −0.2430 | 0.054 | + | SC | ||

| Ku complex | YKU70 | −0.4369 | 0.013 | + | SC | |

| YKU80 | −0.2227 | 0.020 | + | SC | ||

| DNA helicase | RRM3 | −0.5544 | <0.001 | + | + | SC |

| PIF1 | 0.32135 | 0.659 | — | NI | ||

| Spindle assembly checkpoint (SAC) | LTE1 | −0.4332 | 0.029 | + | + | SC |

| BFA1 | −0.3709 | 0.060 | + | + | SC | |

| BUB2 | −0.3067 | 0.019 | + | + | SC | |

| BUB3 | −0.4356 | 0.346 | + | + | SC | |

| Casein kinase 2 | CKB2 | −0.4374 | 0.002 | + | + | SC |

| CKA2 | −0.3128 | 0.117 | — | NI | ||

| CKB1 | −0.2738 | 0.052 | + | + | SC | |

| CKA1 | −0.0636 | 0.779 | — | NI | ||

| Other function | ERG5 | −0.4210 | 0.014 | + | + | SC |

| YPR1 | −0.5277 | 0.047 | — | NI | ||

| CKI1 | −0.8473 | <0.001 | — | NI | ||

| MVB12 | −0.5303 | 0.006 | — | NI | ||

| RUB1 | −0.4708 | 0.006 | — | NI | ||

| FPK1 | −0.4598 | 0.005 | — | NI | ||

| TRE1 | −0.4370 | 0.003 | — | NI | ||

| AGX1 | −0.4214 | <0.001 | — | NI | ||

| RAS1 | −1.128 | <0.001 | — | NI | ||

| HBT1 | −1.1812 | <0.001 | — | NI | ||

| Unknown function | YJR128W | −0.7980 | 0.031 | — | NI | |

| YBR134W | −0.4113 | 0.033 | — | NI | ||

| YCL046W | −0.4728 | 0.008 | — | NI | ||

| YPR063C | −0.5446 | 0.014 | — | NI | ||

| YOR223W | −0.4290 | 0.044 | — | NI | ||

| RRT6 | −0.5046 | 0.037 | — | NI |

The underlined text indicates interactions that did not satisfy the initial P-value <0.05 or interaction magnitude (EC) value <−0.4 cutoffs for SGA analysis but were chosen for further analysis based on the fact that they are part of multisubunit complexes for which at least one component was identified as SC with tel1Δ and CPT. For random spore and tetrad dissection assays, + and − indicate confirmed true and false positives, respectively. NI, no genetic interaction. The absence of a symbol indicates that the interaction was not tested.

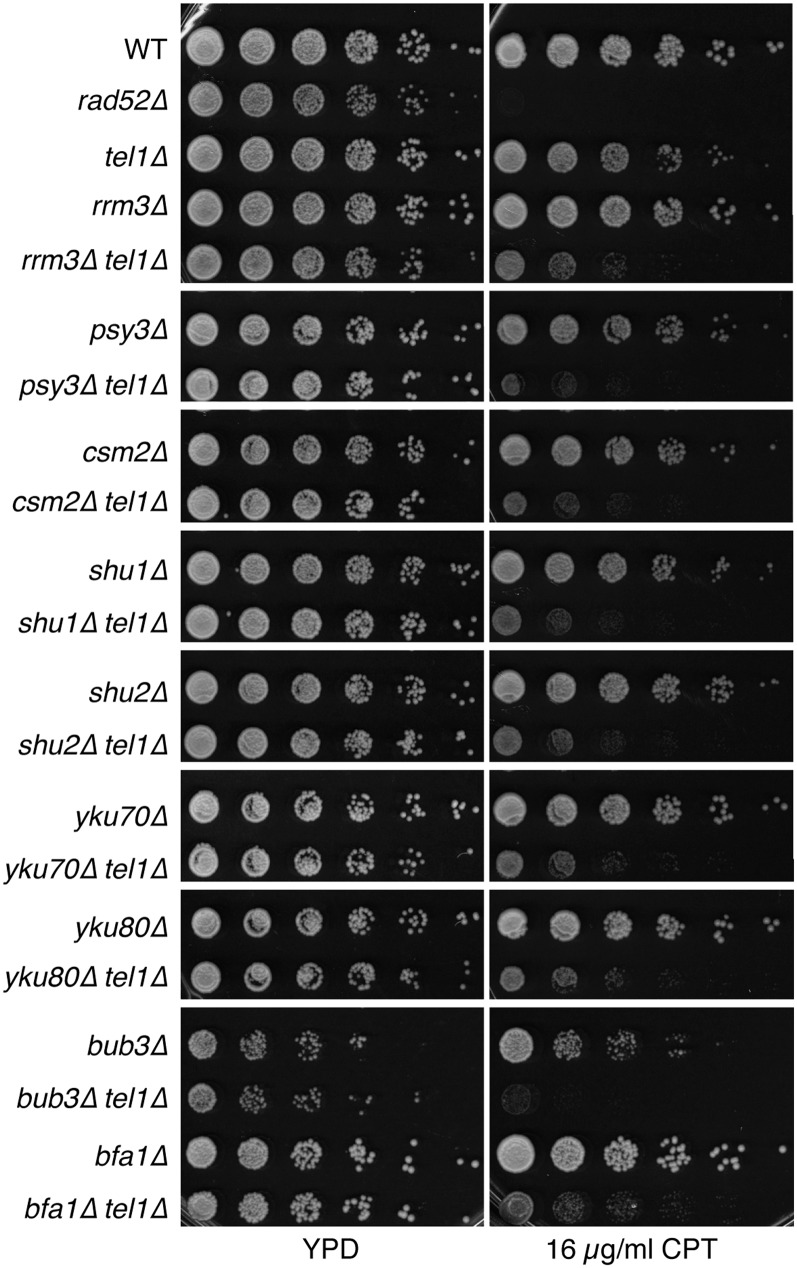

Validation and expansion to related genes

The 22 candidate SC genes identified by SGA were tested by random spore assay or tetrad dissection. Newly constructed haploid strains containing gene-deletion alleles were derived from a heterozygous diploid collection (a gift from Jef Boeke) and used to construct the double-deletion strains for validation. Using alleles from a different source than those used in the SGA increased confidence in the interaction. Newly derived double mutants were tested by spot assays and quantitative liquid growth curve analysis. Of the 22 candidate gene mutations tested, seven showed significant SC interactions with tel1Δ in these validation assays (Table 1).

Five of the seven SC gene mutations were components of multisubunit complexes or processes: CSM2 and PSY3 encode components of the SHU complex, which contains two other subunits, Shu1 and Shu2; LTE1 encodes a component of the spindle assembly checkpoint; YKU80 encodes a protein in the nonhomologous end joining (NHEJ) DNA-repair pathway; and CKB2 encodes one of the β-subunits of the tetrameric casein kinase 2 (CK2). Other components of these pathways or complexes were not identified as SC according to our cutoff criteria in the SGA screen (Table 1). To test if these genes were false negatives, we constructed double mutants with tel1Δ and assayed for SC to CPT by spot assays and growth-curve analysis. We found that deletions of the SHU complex genes SHU1 and SHU2, the NHEJ gene YKU70, the casein kinase 2 subunit CKB1 but not CKA1 or CKA2, and the spindle assembly checkpoint genes BUB1, BFA1, and BUB2 resulted in SC to CPT (Figure 3 and Table 1).

Figure 3.

Validation of SC interactions identified by SGA. Serial dilutions of cells were spotted on YPD plates containing 16 µg/ml CPT to test SC.

Many DNA-repair gene mutants are very sensitive to CPT. These genes were filtered out during analysis because the single mutant was inviable when exposed to 4 µg/ml CPT. To determine if interactions were missed due to sensitivity of single mutants, we used a SGA mini-array containing ∼200 DNA-repair gene mutants and scored for SC with tel1Δ at two concentrations of CPT (1 and 4 µg/ml). At 4 µg/ml CPT, the mini-array identified all of the tel1Δ SC interactions that were identified in the whole nonessential genome SGA and three subunits of the SWI/SNF nucleosome-remodeling complex, SNF2, SNF5, SNF6, that were not detected in the whole nonessential genome screen (Table 2). At 1 µg/ml CPT, the mini-array identified tel1Δ SC interactions with four subunits of the PCNA-like DNA-damage checkpoint complex, DDC1, MEC3, RAD17, RAD24, that were not identified at 4 µg/ml because the single mutants are exquisitely sensitive to CPT. The tel1Δ SC interactions with PCNA-like checkpoint genes are consistent with a previous study (Guenole et al. 2013)

Table 2. Additional SC interactions identified using a mini-array and screening with 1 µg/ml and 4 µg/ml camptothecin.

| Function | Gene | EC value | P-value | 1 µg/ml CPT | 4 µg/ml CPT |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SWI–SNF complexes | SNF2 | −0.7816 | 0.007 | — | SC |

| SNF5 | −0.2278 | 0.008 | — | SC | |

| SNF6 | −0.3235 | 0.304 | — | SC | |

| RRM3 | −0.3059 | 0.042 | SC | ||

| RRM3 | −0.7822 | 0.003 | SC | ||

| BUB3 | −0.3898 | 0.005 | — | SC | |

| SHU complex | SHU1 | −0.3732 | 0.002 | — | SC |

| CSM2 | −0.3269 | 0.004 | — | SC | |

| PSY3 | −0.2323 | 0.012 | — | SC | |

| CHL1 | −0.2994 | 0.002 | — | SC | |

| RecQ–Top3 complex | RMI1 | −0.2913 | 0.030 | — | SC |

| SGS1 | −0.2653 | 0.041 | — | SC | |

| RDH54 | −0.2362 | <0.001 | — | SC | |

| YKU70 | −0.2300 | 0.008 | — | SC | |

| PCNA-like checkpoint | RAD17 | −0.6640 | <0.001 | SC | — |

| RAD24 | −0.6585 | <0.001 | SC | — | |

| DDC1 | −0.5103 | 0.002 | SC | — | |

| MEC3 | −0.4901 | <0.001 | SC | — | |

| HDA1 | −0.2562 | 0.001 | SC | — | |

| SRS2 | −0.2122 | 0.014 | SC | — | |

| SSN8 | −0.2008 | 0.007 | SC | — |

Due to differences in array composition, a larger percentage of slow-growing or DNA-damage-sensitive mutant strains, an EC value <−0.2 was used as a cutoff for SC for the mini-array SGA analysis. Underlined text indicates that the gene was also identified in the larger scale SGA screen.

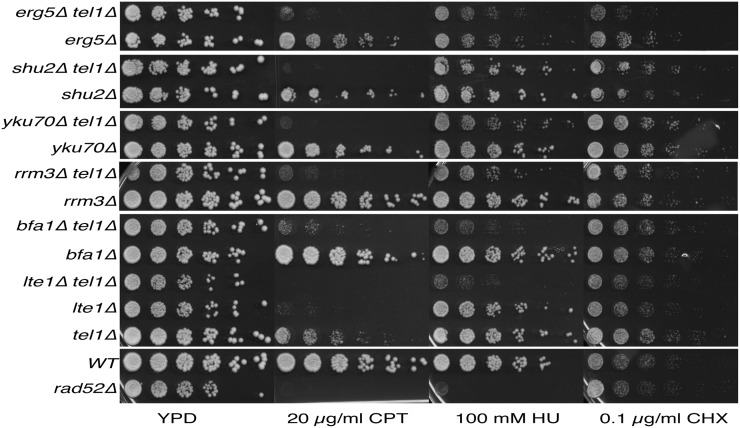

SC is specific to DNA damage and CPT

To test if the SC interactions were specific to DNA damage or were common to other stresses, we tested the fitness of the double mutants in the presence of cycloheximide (CHX), which inhibits protein synthesis. None of the double mutants were SC to CHX, indicating that the identified SC interactions were not due to a general response to stress. Only erg5Δ and erg5Δ tel1Δ were sensitive to treatment with CHX (Figure 4). Cells deleted for genes encoding ergosterol biosynthetic enzymes show sensitivity to many different drugs (Mukhopadhyay et al. 2002; Parsons et al. 2004) suggesting that the SC to CPT observed in erg5Δ tel1Δ was the result of increased intracellular levels of CPT coupled with the loss of Tel1, which is required for resistance to CPT.

Figure 4.

SC with tel1Δ is dependent on the specific DNA-damaging agent. The sensitivity of SC interactions to camptothecin (CPT), hydroxyurea (HU), and cycloheximide (CHX) tested in spot assays.

We next tested whether the SC was specific to CPT by assaying the double mutants for sensitivity to the replication inhibitor HU. Both HU and CPT increase DNA replication stress during S phase leading to DNA damage. However, HU acts by a different mechanism than CPT does. HU is an inhibitor of ribonucleotide reductase, slows replication fork progression, and induces replication fork stalling by reducing dNTP pools (Lopes et al. 2001; Alvino et al. 2007). We found that tel1Δ rrm3Δ, tel1Δ bfa1Δ, and tel1Δ lte1Δ were SC to both CPT and HU, suggesting that these double mutants are sensitive to replication stress in general. In contrast, the SC interactions between tel1Δ and the CKB subunit mutations, SHU complex mutations, and the Ku complex mutations were specific to CPT (Figure 4).

Epistasis of SC groups

To determine if the tel1Δ SC to CPT was due to a common mechanism, we constructed triple mutants with tel1Δ and pairwise combinations of the interacting genes to determine if the SC to CPT was additive or epistatic. Based on sensitivity to CPT we were able to define five genetic epistasis groups: SHU complex genes SHU1, SHU2, CSM2, PSY3; Ku genes YKU70, YKU80; the spindle checkpoint genes BFA1, LTE1, BUB2, BUB3; casein kinase 2 β-subunit genes CKB1, CKB2; and the DNA helicase gene RRM3. Triple mutants displayed additive sensitivity to CPT in the tel1Δ background when knocking out two genes, one gene from each group (Figure S3).

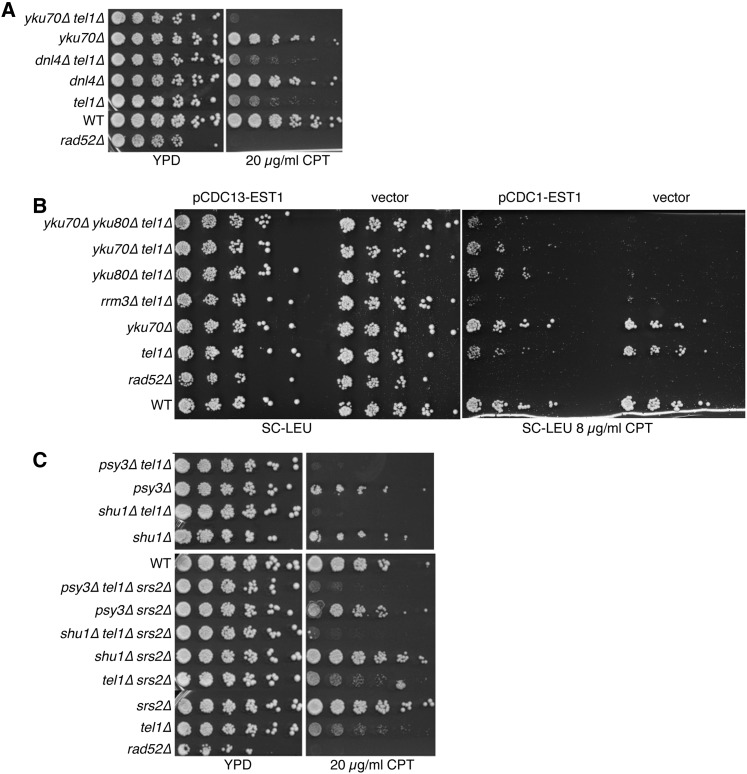

The SC of tel1Δ yku70Δ and tel1Δ yku80Δ is not due to loss of NHEJ

DSBs can be repaired by either homologous recombination (HR), which is the predominant form of repair during late S/G2 phase, or NHEJ, which is the predominant form of repair during G1/early S phase (Mao et al. 2008). As core proteins in NHEJ repair machinery, the Ku70–Ku80 heterodimer is recruited rapidly to DSBs and forms a ring-like structure that binds to DNA ends and initiates NHEJ (Daley et al. 2005). Both yku70Δ and yku80Δ when combined with tel1Δ were SC to CPT and as expected triple tel1Δ yku70Δ yku80Δ mutants did not exhibit more severe SC to CPT (Figure S3). Although both tel1Δ yku70Δ and tel1Δ yku80Δ were SC to CPT, a deletion of the NHEJ-associated DNA ligase, DNL4, did not result in SC to CPT when combined with tel1Δ (Figure 5A). As Dnl4 is essential for NHEJ, the SC to CPT of tel1Δ and yku70Δ or yku80Δ was not due to the loss of NHEJ suggesting an NHEJ-independent mechanism. Recent work has demonstrated that Ku proteins have roles beyond NHEJ repair. Ku proteins protect dsDNA break ends from resection and potentially restrict HR activity (Langerak et al. 2011). However, deletion of MRE11 or EXO1, which are the nucleases required for end resection, did not alleviate the SC of yku70Δ tel1Δ, suggesting that SC was not the result of increased DNA end resection (Figure S4).

Figure 5.

Investigating the mechanism of SC. (A) Comparison of growth of tel1Δ yku70Δ and tel1Δ dnl4Δ mutants on CPT in spot assays. (B) Growth of tel1Δ yku70Δ, tel1Δ yku80Δ, and tel1Δ yku70Δ yku80Δ mutants containing pRS415–CDC13–EST1 or vector alone with and without CPT. (C) Comparison of sensitivity to CPT of tel1Δ psy3Δ, tel1Δ shu1Δ double mutants in the presence and absence of Srs2.

SC to CPT of tel1Δ yku70Δ and tel1Δ yku80Δ is suppressed by telomere lengthening

Mutations in TEL1, YKU70, YKU80, or RRM3 result in the shortening of telomeres (Boulton and Jackson 1998; Ivessa et al. 2002). CPT treatment induces telomeric DNA damage in human cells (Kang et al. 2004). CPT may also affect telomeres in yeast and exacerbate the telomere-shortening defects observed in tel1, rrm3, and yku70/80 mutants. To examine whether telomere elongation can suppress the SC to CPT, we expressed a Cdc13–Est1 fusion protein, which promotes telomere elongation (Evans and Lundblad 1999), in tel1Δ yku70Δ and tel1Δ rrm3Δ. Increasing telomerase activity by expression of Cdc13–Est1 protein suppressed SC to CPT in tel1Δ yku70Δ, tel1Δ yku80Δ, and tel1Δ yku70Δ yku80Δ but did not suppress SC to CPT in tel1Δ rrm3Δ (Figure 5B). These data suggest that the SC to CPT in tel1Δ yku70Δ and tel1Δ yku80Δ is the result of telomere shortening.

Analysis of tel1Δshu1Δ SC

The yeast Shu complex, consisting of Shu1/Shu2/Psy3/Csm2, facilitates efficient HR repair of specific replication-induced lesions (Shor et al. 2005). Shu1 and Psy3 share homologies with the human RAD51 paralogs XRCC2 and RAD51D, respectively, which act as recombination mediators (Martin et al. 2006). It was proposed that the Shu complex stabilizes Rad51 filaments to promote HR by inhibiting the disassembly reaction of the anti-recombinase Srs2 (Bernstein et al. 2011). To determine if the SC was due to increased anti-recombinase activity of Srs2, we deleted SRS2 in psy3Δ tel1Δ and shu1Δ tel1Δ double mutants. In the triple mutant, deletion of SRS2 did not rescue the SC to CPT of tel1Δ psy3Δ or tel1Δ shu1Δ, suggesting that the SC interactions are Srs2 independent (Figure 5C).

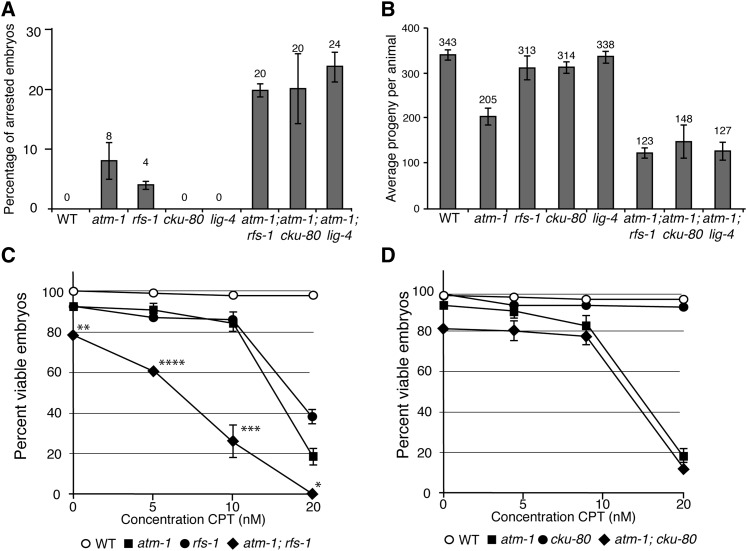

SC interactions are conserved in Caenorhabditis elegans

To determine if the SC interactions observed in yeast were conserved in a more complex organism, we tested two classes of the SC interactions found in yeast in the model metazoan, C. elegans. We first tested whether the SC to CPT of tel1Δ shu1Δ was conserved. C. elegans has a well-characterized Tel1 ortholog, ATM-1 (Garcia-Muse and Boulton. 2005; Bailly et al. 2010; Jones et al. 2012), and a single RAD-51 paralog, RFS-1, which when mutated shares many phenotypic similarities with yeast Shu complex mutants (Ward et al. 2007; Yanowitz 2008; Ward et al. 2010). We constructed atm-1; rfs-1 double mutants and measured the sensitivity of the single and double mutants to a range of CPT concentrations. Even in the absence of CPT, atm-1; rfs-1 double mutants exhibited a reduced brood size and increased frequency of arrested embryos and male progeny, which are phenotypes consistent with increased chromosome instability (Figure 6, A and B, and Figure 7A). The atm-1; rfs-1 double mutant was significantly more sensitive to CPT than either single mutant, demonstrating that the SC interaction was conserved between yeast and C. elegans (Figure 6C).

Figure 6.

Conservation of SC interactions in C. elegans. (A) The percentage of embryonic arrest observed in the progeny of single and double mutants. Error bars represent SEM of at least eight broods. (B) The total brood size (arrested embryos and viable progeny) of self-fertilizing single and double mutants. Error bars represent SEM of at least eight broods. (C) Comparison of sensitivity to CPT of atm-1, rfs-1, and atm-1; rfs-1 mutants. Error bars represent SEM of at least three experiments. (*) P < 1E-2, (**) P < 1E-3, (***) P < 1E-4, (****) P < 1E-5 by Student’s t-test analysis. (D) Comparison of sensitivity to CPT of atm-1, cku-80, and atm-1; cku-80 mutants. Error bars represent SEM of at least three experiments.

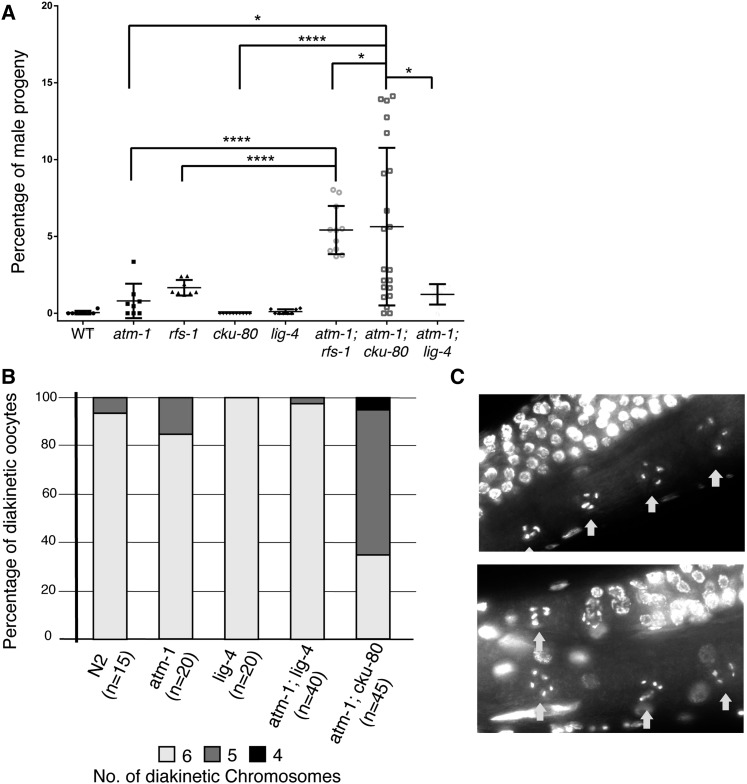

Figure 7.

Conservation of the telomere stability defect in atm-1; cku-80. (A) Frequency of males observed in progeny of single and double mutants. (*) P < 0.05, (****) P < 5E-5. Kolmogorov–Smirnov (KS) test was used instead of Student’s t-test to compare atm-1; cku-80 to the other strains because the frequency of males in different broods did not exhibit a normal distribution. (B) atm-1; cku-80 strains, although viable, exhibit reduced chromosome numbers in diakinesis oocytes, which is indicative of telomere to telomere fusions. (C) Two representative images of diakinesis nuclei of atm-1; cku-80 animals exhibiting a strong Him phenotype.

We next tested whether the yku80Δ tel1Δ SC interaction was conserved in C. elegans. There are C. elegans orthologs of Yku70, Yku80, and Dnl4, CKU-70, CKU-80, and LIG-4, respectively (Boulton et al. 2002; Clejan et al. 2006). We constructed atm-1; cku-80 and atm-1; lig-4 double mutants and analyzed the phenotypes. In the absence of CPT, atm-1; cku-80 and atm-1; lig-4 double mutants showed evidence of increased chromosome instability. However, their phenotypes were markedly different. atm-1; lig-4 double mutants had reduced brood sizes and increased frequency of arrested embryos but no significant increase in the frequency of males when compared to atm-1. In contrast, atm-1; cku-80 mutants exhibited similar reductions in brood size and frequency of arrested embryos compared to atm-1; lig-4 but unlike atm-1; lig-4, atm-1; cku-80 mutants exhibited a high frequency of males, indicating increased X chromosome loss (Figure 7A). The frequency of males in atm-1; cku-80 broods varied greatly between parental animals; some animals gave large broods with few males and arrested embryos while others had severely reduced broods and very high frequencies of males and arrested embryos. As the atm-1 mutant has increased frequency of apparent telomere to telomere chromosome fusions, which can result in a variable high frequency of males (Jones et al. 2012), we examined whether the loss of CKU-80 was exacerbating this phenotype. DAPI staining of the atm-1; cku-80 double mutants that had very high frequencies of males revealed a reduced number of diakinetic chromosomes, suggesting that chromosome fusions had occurred. This phenotype was specific to atm-1; cku-80 and was not observed in atm-1; lig-4 (Figure 7, B and C). Although the overlapping roles of Ku proteins and ATM-1/Tel1 in maintaining telomere stability appears to be conserved between yeast and C. elegans, treatment with CPT did not further exacerbate the interaction between atm-1 and cku-80 in C. elegans. It is possible that the effect of CPT on C. elegans telomeres is not as great as that on yeast telomeres or because the CPT sensitivity assay we employed in C. elegans was not designed to score the effects on telomeres.

Discussion

We screened for genetic interactions with a null mutation of the yeast ATM ortholog, TEL1, that increase the cytotoxicity of the topoisomerase I poison camptothecin. We identified and validated 14 synthetic cytotoxic interactions, demonstrating that applying conditions, such as genotoxic stress, increase the number of genetic interactions that can be potentially exploited for therapy.

Synthetic cytotoxic interactions with DNA-damaging agents and tel1Δ

We found no SL or strong negative genetic interactions with the tel1 null mutant, which is consistent with previous reports (Chatr-Aryamontri et al. 2013). In contrast, mutations affecting the related kinase MEC1 have far more SL interactions (Chatr-Aryamontri et al. 2013). This observation is likely the result of Mec1 having a more prominent role than Tel1 in DDR checkpoint signaling (Morrow et al. 1995; Sanchez et al. 1996; Usui et al. 2001). Application of DNA damage uncovers genetic interactions that are not obvious in the absence of exogenous damage. We, and others, have uncovered genetic interactions with tel1Δ in response to DNA-damaging agents. Two previous studies demonstrated that tel1Δ in combination with mutations affecting 9-1-1 DDR checkpoint genes are more sensitive to CPT, ionizing radiation, and the alkylating agent MMS (Guenole et al. 2013; Piening et al. 2013). Piening and co-workers also identified 10 interactions with tel1Δ that were specific to treatment with MMS. We observed the 9-1-1 checkpoint interactions and 2 of the 10 interactions with MMS, in response to CPT. However, several interactions were specific to CPT. These CPT-specific interactions may be due to the fact that CPT generates DNA–TopI adducts and Tel1 is hyperactivated by DNA ends that are covalently bound to proteins, such as the Top1–DNA adduct (Fukunaga et al. 2011).

Classes of gene mutations that result in increased sensitivity to CPT in tel1 mutants

CK2 is composed of catalytic and regulatory subunits and is ubiquitous in eukaryotic organisms (Pinna 1990). CK2 is involved in a myriad of cellular processes, including cell growth and proliferation and is responsible for phosphorylating >300 substrates, including topoisomerase I and II (Meggio and Pinna 2003). It has been shown that CK2 protein levels and activity are increased in many cancers (Toczyski et al. 1997; Ahmad et al. 2005). The free catalytic subunits of CK2 also display high catalytic activity in the absence of the regulatory subunits, which appear to operate as a docking platform for binding substrates and/or substrate-directed effectors, thus modulating CK2 substrate specificity rather than its activity. Interestingly, we found that CK2 β-subunits, but not α-subunits, exhibit SC to CPT with tel1Δ. CK2β appears to have functions apart from the regulation of CK2 catalytic subunits (Bibby and Litchfield. 2005). In S. cerevisiae, only CK2β mutants show adaptation defects in response to DNA damage and this defect is independent of the catalytic CK2 subunits (Toczyski et al. 1997). In mammalian cells, CK2β is involved in CK2-independent interactions with other proteins, including the DNA-damage checkpoint Chk1 and the HR-associated BRCA1 (O’Brien et al. 1999; Guerra et al. 2003). Given the apparent upregulation of CK2 in tumors, the fact that many CK2 substrates act in the DNA-damage response, and our finding that the loss of the CK2 regulatory subunit results in SC to CPT in tel1Δ, CK2 is a potential target for inhibition in ATM-deficient tumor cells.

The spindle assembly checkpoint is made up of the evolutionarily conserved proteins Bub1, Bub3, Mad1, Mad2, and Mad3. The major trigger of the SAC is unattached kinetochores, which leads to a “wait” signal that pauses anaphase. For example, nocodazole, an inhibitor of microtubule polymerization, destabilizes the spindle and triggers the SAC (Musacchio and Salmon 2007; Lara-Gonzalez and Taylor 2012). In budding yeast, stalled replication forks also activate the SAC to block anaphase. Mutations in MAD2 partially relieve replication defect-induced arrest. The loss of the replication checkpoint kinase MEC1 further relieves the arrest in mad2 mutants, demonstrating the additive nature of the SAC and the replication checkpoint in response to HU-induced replication stalling (Garber and Rine 2002). In fission yeast, a similar coordination of the SAC and DNA replication checkpoint is observed in response to CPT (Collura et al. 2005; Kim and Burke 2008; Chila et al. 2013). The interconnectedness of the SAC and the replication checkpoint is further illustrated by the observations that ATM/Tel1 and ATR/Mec1 can directly affect spindle assembly (Kim and Burke 2008; Smith et al. 2009). Our finding that loss of SAC components results in SC to CPT and HU in tel1Δ is consistent with the role for the SAC in responding to replication stress and the significant interplay between the SAC and the role of ATM/Tel1 in the replication checkpoint.

Rrm3 is a 5′ to 3′ DNA helicase that migrates with the DNA replication fork and relieves replication fork pauses. Loss of Rrm3 results in delayed DNA replication at ∼1000 genomic loci, including tRNA genes, inactive replication origins, centromeres, rDNA repeat, and telomeres (Azvolinsky et al. 2006). Although rrm3Δ cells are DNA-repair proficient, the associated replication defects lead to Mec1/Rad53 checkpoint activation (Taylor et al. 2005; Bochman et al. 2010). Loss of Rrm3 also increases the probability of replication fork stalling and leads to Tel1- and Mec1-dependent phosphorylation of H2A (Szilard et al. 2010). Given the role of Rrm3 in promoting replication progression and the role of Tel1 in the replication checkpoint, it is not surprising that loss of both proteins result in SC when replication is further perturbed by treatment with either CPT or HU.

We found that the SC to CPT of tel1Δ ykuΔ was not due to loss of NHEJ activity but rather due to telomere defects. tel1Δ mutants exhibit abnormally short telomeres (Lustig and Petes 1986) and Tel1 has been shown to associate with short telomeres to promote the recruitment of telomerase and telomere elongation (Hector et al. 2007; Sabourin et al. 2007). Furthermore, Tel1 and Mec1 phosphorylate Cdc13 to promote telomerase activity (Tseng et al. 2009). Mutations affecting the yeast orthologs of the Ku genes are also associated with shortened telomeres (Boulton and Jackson 1996; Porter et al. 1996) and tel1Δ yku70Δ and tel1Δ yku80Δ double mutants have even shorter telomeres than the yku or tel1 single mutants, suggesting that the proteins act independently to promote telomere elongation (Porter et al. 1996; Grandin et al. 2012; Piening et al. 2013). CPT treatment could further affect telomeres, as CPT has been shown to cause telomeric damage in human cells (Kang et al. 2004). CPT-induced telomeric damage coupled with loss of Tel1 and Yku80/Yku70, which function independently to maintain telomere length, could result in SC to CPT through telomere damage and the inability to protect and elongate telomeres. In contrast to the tel1Δ yku80Δ SC to CPT, which was rescued by expression of a Cdc13–EST1 fusion protein, the SC of tel1Δ yku80Δ to MMS was not rescued by Cdc13–EST2 fusion protein (Piening et al. 2013). The differences may be explained by the effects on the telomere of the different DNA-damage lesions caused by MMS and CPT.

Although we did not observe SC to CPT in atm-1; cku-80 C. elegans, we did observe a negative genetic interaction that was associated with telomere maintenance. Based on the high incidence of males and the presence of apparent chromosome fusions, it appears that loss of CKU-80 exacerbates the telomere fusions that occur in the atm-1 mutant (Jones et al. 2012). This was unexpected as loss of YKU-80 alone does not result in obvious telomeric defects in C. elegans (Lowden et al. 2008). Our data suggest that CKU-80 may protect telomeres in the absence of ATM-1 and that the role of CKU-80 is apparent only when telomere length is compromised. It also supports the hypothesis that telomere–telomere chromosome fusions are not the product of nonhomologous end joining as atm-1; cku-80 animals have frequent apparent chromosome fusions. While we did not see an obvious SC to CPT in atm-1; cku-80 based on decreased embryonic viability, it is possible that treatment with CPT exacerbates the telomere defect in the double mutant, which would become apparent only through analysis of the F2 progeny of CPT-treated animals.

We observed SC to CPT when tel1Δ is combined with mutations in components of the Shu complex. The Shu complex has been proposed to mediate the assembly of Rad51 filaments, which are required for HR (Ball et al. 2009; Bernstein et al. 2011; Sasanuma et al. 2013). Recent analysis of the Shu complex demonstrated that there are two Shu subcomplexes, Psy3–Csm2, which constitutes a core subcomplex with DNA-binding activity, and Shu1–Shu2, which results in milder phenotypes than Psy3 or Csm2 when mutated (Tao et al. 2012). Consistent with these data, we found that psy3Δ confers a more severe SC to CPT interaction with tel1Δ than either shu1Δ or shu2Δ. In mammalian cells, the Psy3 homolog, Rad51D, has a role in telomere maintenance (Tarsounas et al. 2004) and in C. elegans, mutations in the RAD51 paralog gene, rfs-1, result in telomeric repeat instability (Yanowitz 2008). However, unlike tel1Δ yku70Δ, elongation of telomeres by expression of the Cdc13–Est1 fusion protein did not suppress the SC of tel1Δ shu1Δ (data not shown). We also showed that increased Srs2 antirecombinase activity, which occurs in the absence of the Shu complex (Bernstein et al. 2011), was not responsible for the SC. The fact that the SC to CPT of tel1Δ and Shu complex mutations was specific to CPT and not HU or the radiomimetic bleomycin suggests that the interaction could be specifically in response to aberrant DNA structures that form at CPT-stalled replication forks. Similar to Shu, which is not essential for HR-mediated DSB repair, the C. elegans RAD51 paralog, RFS-1, is required for RAD-51 foci formation after treatment with genotoxic agents that block replication fork progression such as CPT and interstrand cross-linking agents but not other replication perturbing agents, such as ionizing radiation or hydroxyurea (Ward et al. 2007). Treatment of cells with CPT results in lesions that present a physical barrier to replication and cause replication fork slowing and reversal (Ray Chaudhuri et al. 2012). Based on the SC to CPT when Shu mutations are combined with tel1Δ in yeast and when rfs-1 is combined with atm-1 in the worm, it is possible that the Shu complex and Tel1/ATM-1 define redundant pathways that mediate the loading of Rad51 at sites of CPT-induced replication fork stalls to promote HR-mediated repair or bypass.

Synthetic cytotoxicity as a therapeutic approach

Synthetic lethal-based therapies are emerging as viable antitumor treatments (Chan and Giaccia 2011). The number of tumors susceptible to SL approaches could be increased by identifying genetic interactions that result in synthetic lethality under endogenous conditions that can affect tumors such as hypoxia, aneuploidy, or replication stress, or exogenous (applied) conditions such as increased DNA damage from DNA-damaging therapeutic agents, replication stress from replication inhibitors, or spindle destabilization by microtubule poisons. Identifying these conditional SL interactions can expand the number of tumor genotypes that can be treated by SL approaches. In this study we have defined a subclass of conditional synthetic lethality that we have called synthetic cytotoxicity. By exploiting genetic interactions, synthetic cytotoxicity has the potential to expand the spectrum of tumor genotypes that can be targeted for cytotoxic therapy and can lead to lower doses of cytotoxic therapeutic agents, which could reduce off-target cytotoxicity.

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge B. Young and C. Loewen for the use of their Singer SGA Robot and their expertise in SGA screening. C. elegans strains were provided by the Caenorhabditis Genetics Center, which is funded by National Institutes of Health (NIH) Office of Research Infrastructure Programs (P40 OD010440). P. Hieter is a Senior Fellow in the Genetic Networks program at the Canadian Institute for Advanced Research. This work was funded by Canadian Cancer Society Research Institute Innovation grant 701155.

Footnotes

Communicating editor: J. A. Nickoloff

Literature Cited

- Ahmad K. A., Wang G., Slaton J., Unger G., Ahmed K., 2005. Targeting CK2 for cancer therapy. Anticancer Drugs 16: 1037–1043 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alvino G. M., Collingwood D., Murphy J. M., Delrow J., Brewer B. J., et al. , 2007. Replication in hydroxyurea: it’s a matter of time. Mol. Cell. Biol. 27: 6396–6406 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Azvolinsky A., Dunaway S., Torres J. Z., Bessler J. B., Zakian V. A., 2006. The S. cerevisiae Rrm3p DNA helicase moves with the replication fork and affects replication of all yeast chromosomes. Genes Dev. 20: 3104–3116 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bailly A. P., Freeman A., Hall J., Declais A. C., Alpi A., et al. , 2010. The Caenorhabditis elegans homolog of Gen1/Yen1 resolvases links DNA damage signaling to DNA double-strand break repair. PLoS Genet. 6: e1001025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ball L. G., Zhang K., Cobb J. A., Boone C., Xiao W., 2009. The yeast shu complex couples error-free post-replication repair to homologous recombination. Mol. Microbiol. 73: 89–102 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bandyopadhyay S., Mehta M., Kuo D., Sung M. K., Chuang R., et al. , 2010. Rewiring of genetic networks in response to DNA damage. Science 330: 1385–1389 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernstein K. A., Reid R. J., Sunjevaric I., Demuth K., Burgess R. C., et al. , 2011. The shu complex, which contains Rad51 paralogues, promotes DNA repair through inhibition of the Srs2 anti-recombinase. Mol. Biol. Cell 22: 1599–1607 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bibby A. C., Litchfield D. W., 2005. The multiple personalities of the regulatory subunit of protein kinase CK2: CK2 dependent and CK2 independent roles reveal a secret identity for CK2beta. Int. J. Biol. Sci. 1: 67–79 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bochman M. L., Sabouri N., Zakian V. A., 2010. Unwinding the functions of the Pif1 family helicases. DNA Repair 9: 237–249 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boulton S. J., Jackson S. P., 1996. Identification of a Saccharomyces cerevisiae Ku80 homologue: roles in DNA double strand break rejoining and in telomeric maintenance. Nucleic Acids Res. 24: 4639–4648 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boulton S. J., Jackson S. P., 1998. Components of the ku-dependent non-homologous end-joining pathway are involved in telomeric length maintenance and telomeric silencing. EMBO J. 17: 1819–1828 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boulton S. J., Gartner A., Reboul J., Vaglio P., Dyson N., et al. , 2002. Combined functional genomic maps of the C. elegans DNA damage response. Science 295: 127–131 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brachmann C. B., Davies A., Cost G. J., Caputo E., Li J., et al. , 1998. Designer deletion strains derived from Saccharomyces cerevisiae S288C: a useful set of strains and plasmids for PCR-mediated gene disruption and other applications. Yeast 14: 115–132 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Budd M. E., Tong A. H., Polaczek P., Peng X., Boone C., et al. , 2005. A network of multi-tasking proteins at the DNA replication fork preserves genome stability. PLoS Genet. 1: e61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chakhparonian M., Faucher D., Wellinger R. J., 2005. A mutation in yeast Tel1p that causes differential effects on the DNA damage checkpoint and telomere maintenance. Curr. Genet. 48: 310–322 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chan D. A., Giaccia A. J., 2011. Harnessing synthetic lethal interactions in anticancer drug discovery. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 10: 351–364 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Charames G. S., Bapat B., 2003. Genomic instability and cancer. Curr. Mol. Med. 3: 589–596 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chatr-Aryamontri A., Breitkreutz B. J., Heinicke S., Boucher L., Winter A., et al. , 2013. The BioGRID interaction database: 2013 update. Nucleic Acids Res. 41: D816–D823 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chila R., Celenza C., Lupi M., Damia G., Carrassa L., 2013. Chk1-Mad2 interaction: a crosslink between the DNA damage checkpoint and the mitotic spindle checkpoint. Cell Cycle 12: 1083–1090 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clejan I., Boerckel J., Ahmed S., 2006. Developmental modulation of nonhomologous end joining in Caenorhabditis elegans. Genetics 173: 1301–1317 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collins S. R., Miller K. M., Maas N. L., Roguev A., Fillingham J., et al. , 2007. Functional dissection of protein complexes involved in yeast chromosome biology using a genetic interaction map. Nature 446: 806–810 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collura A., Blaisonneau J., Baldacci G., Francesconi S., 2005. The fission yeast Crb2/Chk1 pathway coordinates the DNA damage and spindle checkpoint in response to replication stress induced by topoisomerase I inhibitor. Mol. Cell. Biol. 25: 7889–7899 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Costanzo M., Baryshnikova A., Bellay J., Kim Y., Spear E. D., et al. , 2010. The genetic landscape of a cell. Science 327: 425–431 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daley J. M., Palmbos P. L., Wu D., Wilson T. E., 2005. Nonhomologous end joining in yeast. Annu. Rev. Genet. 39: 431–451 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evans S. K., Lundblad V., 1999. Est1 and Cdc13 as comediators of telomerase access. Science 286: 117–120 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fritz E., Friedl A. A., Zwacka R. M., Eckardt-Schupp F., Meyn M. S., 2000. The yeast TEL1 gene partially substitutes for human ATM in suppressing hyperrecombination, radiation-induced apoptosis and telomere shortening in A-T cells. Mol. Biol. Cell 11: 2605–2616 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fukunaga K., Kwon Y., Sung P., Sugimoto K., 2011. Activation of protein kinase Tel1 through recognition of protein-bound DNA ends. Mol. Cell. Biol. 31: 1959–1971 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garber P. M., Rine J., 2002. Overlapping roles of the spindle assembly and DNA damage checkpoints in the cell-cycle response to altered chromosomes in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Genetics 161: 521–534 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garcia-Muse T., Boulton S. J., 2005. Distinct modes of ATR activation after replication stress and DNA double-strand breaks in Caenorhabditis elegans. EMBO J. 24: 4345–4355 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grandin N., Corset L., Charbonneau M., 2012. Genetic and physical interactions between Tel2 and the Med15 mediator subunit in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. PLoS ONE 7: e30451. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guenole A., Srivas R., Vreeken K., Wang Z. Z., Wang S., et al. , 2013. Dissection of DNA damage responses using multiconditional genetic interaction maps. Mol. Cell 49: 346–358 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guerra B., Issinger O. G., Wang J. Y., 2003. Modulation of human checkpoint kinase Chk1 by the regulatory beta-subunit of protein kinase CK2. Oncogene 22: 4933–4942 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gumy-Pause F., Wacker P., Sappino A. P., 2004. ATM gene and lymphoid malignancies. Leukemia 18: 238–242 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hall J., 2005. The ataxia-telangiectasia mutated gene and breast cancer: gene expression profiles and sequence variants. Cancer Lett. 227: 105–114 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hartwell L. H., Szankasi P., Roberts C. J., Murray A. W., Friend S. H., 1997. Integrating genetic approaches into the discovery of anticancer drugs. Science 278: 1064–1068 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hector R. E., Shtofman R. L., Ray A., Chen B. R., Nyun T., et al. , 2007. Tel1p preferentially associates with short telomeres to stimulate their elongation. Mol. Cell 27: 851–858 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Helleday T., Petermann E., Lundin C., Hodgson B., Sharma R. A., 2008. DNA repair pathways as targets for cancer therapy. Nat. Rev. Cancer 8: 193–204 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ivessa A. S., Zhou J. Q., Schulz V. P., Monson E. K., Zakian V. A., 2002. Saccharomyces Rrm3p, a 5′ to 3′ DNA helicase that promotes replication fork progression through telomeric and subtelomeric DNA. Genes Dev. 16: 1383–1396 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones M. R., Huang J. C., Chua S. Y., Baillie D. L., Rose A. M., 2012. The atm-1 gene is required for genome stability in Caenorhabditis elegans. Mol. Genet. Genomics 287: 325–335 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kang B., Guo R. F., Tan X. H., Zhao M., Tang Z. B., et al. , 2008. Expression status of ataxia-telangiectasia-mutated gene correlated with prognosis in advanced gastric cancer. Mutat. Res. 638: 17–25 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kang M. R., Muller M. T., Chung I. K., 2004. Telomeric DNA damage by topoisomerase I: a possible mechanism for cell killing by camptothecin. J. Biol. Chem. 279: 12535–12541 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim E. M., Burke D. J., 2008. DNA damage activates the SAC in an ATM/ATR-dependent manner, independently of the kinetochore. PLoS Genet. 4: e1000015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Langerak P., Mejia-Ramirez E., Limbo O., Russell P., 2011. Release of ku and MRN from DNA ends by Mre11 nuclease activity and Ctp1 is required for homologous recombination repair of double-strand breaks. PLoS Genet. 7: e1002271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lara-Gonzalez P., Taylor S. S., 2012. Cohesion fatigue explains why pharmacological inhibition of the APC/C induces a spindle checkpoint-dependent mitotic arrest. PLoS ONE 7: e49041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lavin M. F., 2008. Ataxia-telangiectasia: from a rare disorder to a paradigm for cell signalling and cancer. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 9: 759–769 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lopes M., Cotta-Ramusino C., Pellicioli A., Liberi G., Plevani P., et al. , 2001. The DNA replication checkpoint response stabilizes stalled replication forks. Nature 412: 557–561 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lowden M. R., Meier B., Lee T. W., Hall J., Ahmed S., 2008. End joining at Caenorhabditis elegans telomeres. Genetics 180: 741–754 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lustig A. J., Petes T. D., 1986. Identification of yeast mutants with altered telomere structure. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 83: 1398–1402 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mani R., St Onge R. P., Hartman J. L., 4th, Giaever G., Roth F. P., 2008. Defining genetic interaction. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 105: 3461–3466 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mao Z., Bozzella M., Seluanov A., Gorbunova V., 2008. DNA repair by nonhomologous end joining and homologous recombination during cell cycle in human cells. Cell Cycle 7: 2902–2906 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin V., Chahwan C., Gao H., Blais V., Wohlschlegel J., et al. , 2006. Sws1 is a conserved regulator of homologous recombination in eukaryotic cells. EMBO J. 25: 2564–2574 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLellan J. L., O’Neil N. J., Barrett I., Ferree E., van Pel D. M., et al. , 2012. Synthetic lethality of cohesins with PARPs and replication fork mediators. PLoS Genet. 8: e1002574. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McManus K. J., Barrett I. J., Nouhi Y., Hieter P., 2009. Specific synthetic lethal killing of RAD54B-deficient human colorectal cancer cells by FEN1 silencing. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 106: 3276–3281 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meggio F., Pinna L. A., 2003. One-thousand-and-one substrates of protein kinase CK2? FASEB J. 17: 349–368 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morrow D. M., Tagle D. A., Shiloh Y., Collins F. S., Hieter P., 1995. TEL1, an S. cerevisiae homolog of the human gene mutated in ataxia telangiectasia, is functionally related to the yeast checkpoint gene MEC1. Cell 82: 831–840 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mukhopadhyay K., Kohli A., Prasad R., 2002. Drug susceptibilities of yeast cells are affected by membrane lipid composition. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 46: 3695–3705 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Musacchio A., Salmon E. D., 2007. The spindle-assembly checkpoint in space and time. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 8: 379–393 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Brien K. A., Lemke S. J., Cocke K. S., Rao R. N., Beckmann R. P., 1999. Casein kinase 2 binds to and phosphorylates BRCA1. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 260: 658–664 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pan X., Yuan D. S., Xiang D., Wang X., Sookhai-Mahadeo S., et al. , 2004. A robust toolkit for functional profiling of the yeast genome. Mol. Cell 16: 487–496 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pan X., Ye P., Yuan D. S., Wang X., Bader J. S., et al. , 2006. A DNA integrity network in the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Cell 124: 1069–1081 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parsons A. B., Brost R. L., Ding H., Li Z., Zhang C., et al. , 2004. Integration of chemical-genetic and genetic interaction data links bioactive compounds to cellular target pathways. Nat. Biotechnol. 22: 62–69 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piening B. D., Huang D., Paulovich A. G., 2013. Novel connections between DNA replication, telomere homeostasis, and the DNA damage response revealed by a genome-wide screen for TEL1/ATM interactions in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Genetics 193: 1117–1133 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pinna L. A., 1990. Casein kinase 2: An ’eminence grise’ in cellular regulation? Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1054: 267–284 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Porter S. E., Greenwell P. W., Ritchie K. B., Petes T. D., 1996. The DNA-binding protein Hdf1p (a putative ku homologue) is required for maintaining normal telomere length in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Nucleic Acids Res. 24: 582–585 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ray Chaudhuri A., Hashimoto Y., Herrador R., Neelsen K. J., Fachinetti D., et al. , 2012. Topoisomerase I poisoning results in PARP-mediated replication fork reversal. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 19: 417–423 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Renwick A., Thompson D., Seal S., Kelly P., Chagtai T., et al. , 2006. ATM mutations that cause ataxia-telangiectasia are breast cancer susceptibility alleles. Nat. Genet. 38: 873–875 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roberts N. J., Jiao Y., Yu J., Kopelovich L., Petersen G. M., et al. , 2012. ATM mutations in patients with hereditary pancreatic cancer. Cancer. Discov. 2: 41–46 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sabourin M., Tuzon C. T., Zakian V. A., 2007. Telomerase and Tel1p preferentially associate with short telomeres in S. cerevisiae. Mol. Cell 27: 550–561 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanchez Y., Desany B. A., Jones W. J., Liu Q., Wang B., et al. , 1996. Regulation of RAD53 by the ATM-like kinases MEC1 and TEL1 in yeast cell cycle checkpoint pathways. Science 271: 357–360 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sasanuma H., Tawaramoto M. S., Lao J. P., Hosaka H., Sanda E., et al. , 2013. A new protein complex promoting the assembly of Rad51 filaments. Nat. Commun. 4: 1676. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Savitsky K., Bar-Shira A., Gilad S., Rotman G., Ziv Y., et al. , 1995. A single ataxia telangiectasia gene with a product similar to PI-3 kinase. Science 268: 1749–1753 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schvartzman J. M., Sotillo R., Benezra R., 2010. Mitotic chromosomal instability and cancer: Mouse modelling of the human disease. Nat. Rev. Cancer 10: 102–115 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shiloh Y., 2003. ATM and related protein kinases: safeguarding genome integrity. Nat. Rev. Cancer 3: 155–168 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shor E., Weinstein J., Rothstein R., 2005. A genetic screen for top3 suppressors in Saccharomyces cerevisiae identifies SHU1, SHU2, PSY3 and CSM2: four genes involved in error-free DNA repair. Genetics 169: 1275–1289 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith E., Dejsuphong D., Balestrini A., Hampel M., Lenz C., et al. , 2009. An ATM- and ATR-dependent checkpoint inactivates spindle assembly by targeting CEP63. Nat. Cell Biol. 11: 278–285 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stankovic T., Stewart G. S., Byrd P., Fegan C., Moss P. A., et al. , 2002. ATM mutations in sporadic lymphoid tumours. Leuk. Lymphoma 43: 1563–1571 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stark C., Breitkreutz B. J., Reguly T., Boucher L., Breitkreutz A., et al. , 2006. BioGRID: a general repository for interaction datasets. Nucleic Acids Res. 34: D535–D539 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Szilard R. K., Jacques P. E., Laramee L., Cheng B., Galicia S., et al. , 2010. Systematic identification of fragile sites via genome-wide location analysis of gamma-H2AX. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 17: 299–305 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tao Y., Li X., Liu Y., Ruan J., Qi S., et al. , 2012. Structural analysis of shu proteins reveals a DNA binding role essential for resisting damage. J. Biol. Chem. 287: 20231–20239 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tarsounas M., Munoz P., Claas A., Smiraldo P. G., Pittman D. L., et al. , 2004. Telomere maintenance requires the RAD51D recombination/repair protein. Cell 117: 337–347 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor S. D., Zhang H., Eaton J. S., Rodeheffer M. S., Lebedeva M. A., et al. , 2005. The conserved Mec1/Rad53 nuclear checkpoint pathway regulates mitochondrial DNA copy number in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol. Biol. Cell 16: 3010–3018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson D., Antoniou A. C., Jenkins M., Marsh A., Chen X., et al. , 2005. Two ATM variants and breast cancer risk. Hum. Mutat. 25: 594–595 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toczyski D. P., Galgoczy D. J., Hartwell L. H., 1997. CDC5 and CKII control adaptation to the yeast DNA damage checkpoint. Cell 90: 1097–1106 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tong A. H., Boone C., 2006. Synthetic genetic array analysis in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Methods Mol. Biol. 313: 171–192 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tong A. H., Evangelista M., Parsons A. B., Xu H., Bader G. D., et al. , 2001. Systematic genetic analysis with ordered arrays of yeast deletion mutants. Science 294: 2364–2368 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tong A. H., Lesage G., Bader G. D., Ding H., Xu H., et al. , 2004. Global mapping of the yeast genetic interaction network. Science 303: 808–813 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tseng S. F., Shen Z. J., Tsai H. J., Lin Y. H., Teng S. C., 2009. Rapid Cdc13 turnover and telomere length homeostasis are controlled by Cdk1-mediated phosphorylation of Cdc13. Nucleic Acids Res. 37: 3602–3611 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Usui T., Ogawa H., Petrini J. H., 2001. A DNA damage response pathway controlled by Tel1 and the Mre11 complex. Mol. Cell 7: 1255–1266 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Pel D. M., Barrett I. J., Shimizu Y., Sajesh B. V., Guppy B. J., et al. , 2013. An evolutionarily conserved synthetic lethal interaction network identifies FEN1 as a broad-spectrum target for anticancer therapeutic development. PLoS Genet. 9: e1003254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ward J. D., Barber L. J., Petalcorin M. I., Yanowitz J., Boulton S. J., 2007. Replication blocking lesions present a unique substrate for homologous recombination. EMBO J. 26: 3384–3396 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ward J. D., Muzzini D. M., Petalcorin M. I., Martinez-Perez E., Martin J. S., et al. , 2010. Overlapping mechanisms promote postsynaptic RAD-51 filament disassembly during meiotic double-strand break repair. Mol. Cell 37: 259–272 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yanowitz J. L., 2008. Genome integrity is regulated by the Caenorhabditis elegans Rad51D homolog rfs-1. Genetics 179: 249–262 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao X., Muller E. G., Rothstein R., 1998. A suppressor of two essential checkpoint genes identifies a novel protein that negatively affects dNTP pools. Mol. Cell 2: 329–340 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]