Abstract

Autism is a disabling neurodevelopmental disorder characterized by social deficits, language impairment, and repetitive behaviors with few effective treatments. New evidence suggests that autism has reliable electrophysiological endophenotypes and that these measures may be caused by n-methyl-d-aspartic acid receptor (NMDAR) disruption on parvalbumin (PV)-containing interneurons. These findings could be used to create new translational biomarkers. Recent developments have allowed for cell-type selective knockout of NMDARs in order to examine the perturbations caused by disrupting specific circuits. This study examines several electrophysiological and behavioral measures disrupted in autism using a PV-selective reduction in NMDA R1 subunit. Mouse electroencephalograph (EEG) was recorded in response to auditory stimuli. Event-related potential (ERP) component amplitude and latency analysis, social testing, and premating ultrasonic vocalizations (USVs) recordings were performed. Correlations were examined between the ERP latency and behavioral measures. The N1 ERP latency was delayed, sociability was reduced, and mating USVs were impaired in PV-selective NMDA Receptor 1 Knockout (NR1 KO) as compared with wild-type mice. There was a significant correlation between N1 latency and sociability but not between N1 latency and premating USV power or T-maze performance. The increases in N1 latency, impaired sociability, and reduced vocalizations in PV-selective NR1 KO mice mimic similar changes found in autism. Electrophysiological changes correlate to reduced sociability, indicating that the local circuit mechanisms controlling N1 latency may be utilized in social function. Therefore, we propose that behavioral and electrophysiological alterations in PV-selective NR1 KO mice may serve as a useful model for therapeutic development in autism.

Keywords: autism, electrophysiology, endophenotype, animal models, NMDA receptor 1 knockout

Introduction

Autism spectrum disorders (ASDs) are characterized by core deficits in social and language function. Despite sustained efforts, many of the deficits remain recalcitrant to treatment. One reason for the lack of effective treatments is the lack of predictive translational disease models. Therefore, having more predictive models that recreate the behavioral and electrophysiological changes present in autism would help aid the development of new therapeutics.

Several recent findings provide guidance for preclinical model development for ASD. First, genetic and postmortem studies indicate that the pathophysiology of ASD may include a component of n-methyl-d-aspartic acid receptor (NMDAR) disruption [Bangash et al. 2011]. It is important to note, however, that several endophentypes are common to both schizophrenia and autism. For example, both disorders are characterized by social and communication deficits. Alternatively, there are some endophenotypes that are mutually exclusive, most notably that event-related potentials (ERPs) are reduced in amplitude in schizophrenia but not in ASD, while they are delayed in ASD but not in schizophrenia [Hanlon et al. 2005; Roberts et al. 2010; Mazhari et al. 2011]. Additionally, NMDAR disruption has also been closely linked to schizophrenia [Javitt et al. 2000]. This NMDAR dysfunction in schizophrenia has been associated with changes on parvalbumin (PV)-positive interneurons. A study of mice with reduced NMDA receptors on PV cells evaluated this hypothesis using prepulse inhibition (PPI) of startle and locomotor testing, which are used to evaluate psychosis-like symptoms relevant to schizophrenia [Carlen et al. 2011]. The investigators concluded that PV-NR1 (NMDA Receptor 1) transgenic mice performed similarly to wild-type (WT) mice in these tasks, suggesting that they do not possess positive symptom validity or specificity for schizophrenia.

Alterations of PV-containing interneurons have also been implicated in autism. Postmortem neuropathologic data demonstrate a reduction of PV-immunoreactive interneurons in schizophrenia and an increased density of such cells in ASD [Gonzalez-Burgos & Lewis, 2012; Lawrence et al. 2010]. Additionally, PV cells display an immature profile of gene expression in both ASD and schizophrenia [Gandal et al. 2012]. Consistent with these findings, a meta-analysis of mouse models of ASD indicate that reduction of PV interneurons is a common feature [Gogolla et al. 2009]. Similarly, a variety of studies now demonstrate that subjects with ASD have electroencephalograph (EEG) abnormalities that are consistent with alterations of circuits that rely upon PV interneuron integrity [Dinstein et al. 2011; Roberts et al. 2010; Rojas et al. 2008, 2011; Sohal et al. 2009].

Studies in children with ASD using magnetoencephalography (MEG) have elucidated novel neural biomarkers for the disorder, which could be translated into animal EEG models [Roberts et al. 2010]. Specifically, children with ASD show a delay in the M100, the MEG analogue to the EEG N100, in superior temporal gyrus, with this latency prolongation providing a high degree of accuracy for ASD classification. There is also evidence that these electrophysiological markers are predictive of language impairment [Oram Cardy et al. 2008; Roberts et al. 2011].

EEG measures could potentially provide biomarkers that quantify the degree of impairment in neural circuits that control social behavior along with providing more focused guidance for treatment development [Edgar, Keller, Heller, & Miller, 2007]. These measures have advantages in their translatability between mice and humans. For instance, human auditory-evoked responses have a P50 (P1) and N100 (N1), which display similar morphology and drug responses as the mouse P20 (P1) and N40 (N1) [Amann et al. 2010]. These measures can also be examined using MEG, which has magnetic analogs including the M50 and M100.

In addition, animal models of social behaviors have been developed as translational platforms for examining human sociability. The social choice task examines the preference of a test mouse for same sex mouse as compared with an inanimate object. Given the reduced preference for social interactions in autism, this task attempts to model such behaviors. Additionally, there are typical language impairments in patients with autism. In mice, one model of this language impairment is examining the characteristic patterns of 70 kHz premating ultrasonic vocalizations (USVs). In this task, a male mouse that is exposed to a target female will vocalize at 70 kHz prior to mating.

The current study tests the hypothesis that reduction of NMDA receptor activity only in PV-containing interneurons will disrupt circuits involved in midlatency-evoked response regulation, sociability, and situation-appropriate (premating) USVs. We propose that quantifying the extent to which clinical ASD markers are recapitulated in this model will be a critical step toward evaluating its predictive validity for therapeutic development.

Methods

Subjects

Homozygous PV-cre/cre mice (B6;129P2-Pvalbtm1(cre)Arbr/J) as well as a homozygous NMDA-receptor1-flox/flox mice (NR1-fl/fl; B6.129S4-Grin1tm2Stl/J) were purchased from The Jackson Laboratory (Bar Harbor, ME). Homozygous PV-cre/cre mice were bred with homozygous NR1-fl/fl mice. The offspring, heterozygous PVcre/+;NR1-fl/+, were backcrossed with homozygous PV-cre/cre mice in order to obtain mice homozygous PV-cre/cre and heterozygous NR1-fl/+. The PV-cre/cre;NR1-fl/+mice were then crossed with one another in order to obtain the following genotypes: PV-cre/cre;NR1fl/fl (referred to as PV-selective NR1 KO), PV-cre/cre;NR1-+/+ (referred to as WT). These mice have been characterized in a previous publication by Carlen et al. [2011]. A total of ten WT and eight PV-selective NR1 KO mice were tested against the full battery of measures. All testing was conducted between 10 and 18 weeks of age. Mice were acclimated to the animal facility for at least 7 days before experimentation began and were housed four to five per cage until implantation of the recording electrode, after which they were single-housed for the remainder of the study. All subjects were maintained in a standard 12-hr light/dark cycle with free access to food and water. Experiments were performed during the light phase between 9:00 AM and 4:00 PM. All protocols were conducted in accordance with University Laboratory Animal Resources guidelines and were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at the University of Pennsylvania. All efforts were undertaken to minimize the number of animals used in the experiment and their suffering.

Electrode implantation

At 12 weeks of age, animals underwent stereotaxic implantation of a stainless steel tripolar electrode assembly (Plastics1, Roanoke, VA) as published [Gandal et al. 2008]. Animals were anesthetized with isoflurane, and a low-impedance (5 k, 1000 Hz) macroelectrode was stereotaxically positioned between the auditory cortex and the auditory thalamus (1.8 mm posterior, 2.65 mm lateral, 2.75 mm deep relative to bregma), and referenced to the frontal sinus. This configuration captures both early and late components of the auditory-evoked potential (AEP),including the midlatency P1 (human P50/M50) and N1 (human N100/M100) as published [Siegel et al. 2003]. The electrode pedestal was secured to the skull using ethyl cyanoacrylate (Loctite, Henkel, Germany) and dental cement (Ortho Jet, Lang Dental, Wheeling, IL). EEG was recorded 1 week later, as described later.

Electrophysiological recordings

EEG was recorded with Micro1401 hardware and Spike6 software (CED, Cambridge, UK) as published previously [Ehrlichman et al. 2009]. A total of 200 white noise clicks were presented with an 8-sec interstimulus interval at 85 dB.

Electrophysiology analysis

The amplitude and latency were calculated for P1 (defined as the most positive deflection between 10 and 30 msec) and the N1 (defined as the most negative deflection between 30 and 80 msec). These components of the mouse ERP recording occur at approximately 40% of the latency but occur with similar morphology, pharmacology, and psychophysiology to the equivalent human components [Siegel et al. 2003; Umbricht et al. 2004]. Therefore, the P1 and N1 represent ERP deflections in mice analogous to the P50 and N100 in humans [Amann et al. 2010]. Amplitude was calculated relative to zero, and latency was calculated in milliseconds after stimulus onset.

USV testing

Adult mice do not emit USVs spontaneously but do so when placed in certain contexts involving social interaction [Scattoni et al. 2009]. When paired with a female mouse, male mice will emit “premating” and “mating” vocalizations [Ricceri et al. 2007]. During the premating phase prior to mount, the male emits predominantly 70 kHz vocalizations, which help to coordinate the mating process. While being more narrowly focused than the full range of human language, it is a situation-appropriate pattern of vocal communication that results in a socially appropriate change in behavior in another mouse.

For the adult mating paradigm, the test mouse was paired with an unfamiliar, sexual-receptive female wild-type mouse in a clean cage within a sound-attenuated chamber for 5 min, as has been investigated in other mouse models of ASDs [Jamain et al. 2008]. For the mating task, USVs were recorded with an ultrasonic-range microphone suspended 10 cm above the cage.

USV analysis

Data from USV paradigms were analyzed according to spectral power of the calls, as previously done [Gourbal et al. 2004; Maggio & Whitney, 1985; Ricceri et al. 2007; White et al. 1998]. Spectral analysis was done as follows. Vocalization data were analyzed in the frequency domain by computing the Fast Fourier Transform (FFT) of the entire epoch. Power was computed in decibels and the sum averaged from 40 to 80 kHz. Significance was assessed with an unpaired t-test. To address the association between receptive auditory processing and expressive communicative functioning, dependent measures from USV paradigms were correlated with AEP indices within each mouse. Pearson R2 correlations were calculated for AEP and USV measures. Correlations were assessed within electrophysiological and behavioral measures, assessing the relationship, for example, between adult mating vocalizations and N1 latency.

Sociability testing

We previously demonstrated that constitutive reduction of NMDAR1 and the NMDA receptor-related protein neuregulin 1 result in reduced social interactions [Ehrlichman et al. 2009; Halene et al. 2009]. As such, we and others have suggested that impaired NMDAR signaling may contribute to social deficits in autism. Social interactions were assessed as previously published [Ehrlichman et al. 2009].

T-maze

PV-selective NR1 KO and WT mice were assessed for working memory function according to published methods for discrete T-maze [Deacon & Rawlins, 2006]. Data were collected using a 1-sec delay, which has been shown to require hippocampal as well as frontal contributions. Unpaired t-tests were used to compare effects between groups.

Results

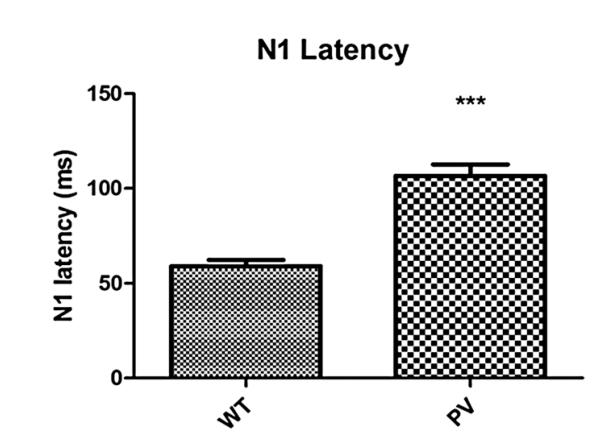

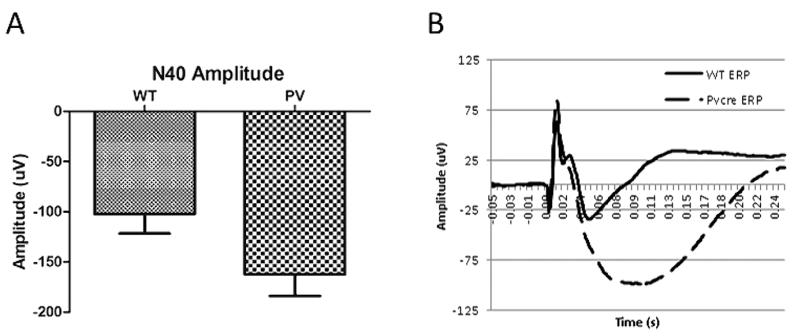

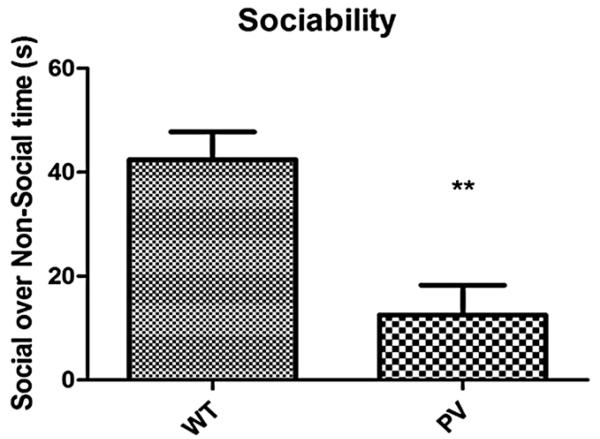

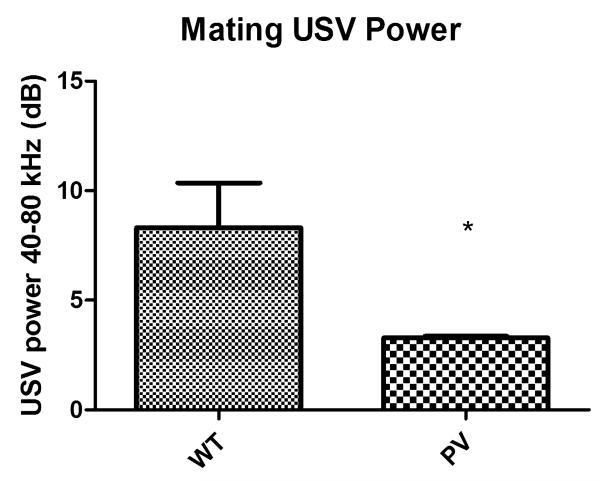

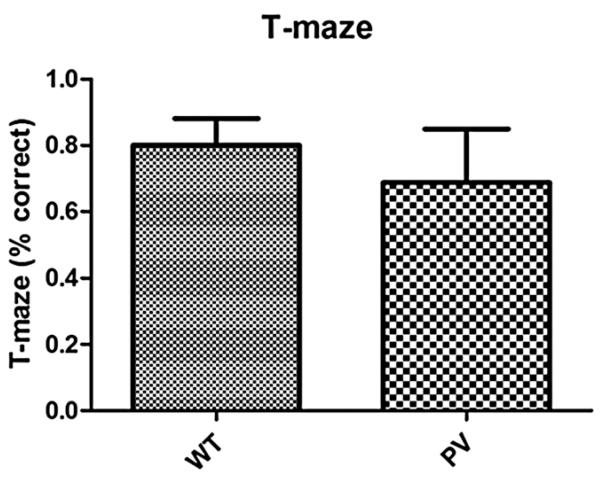

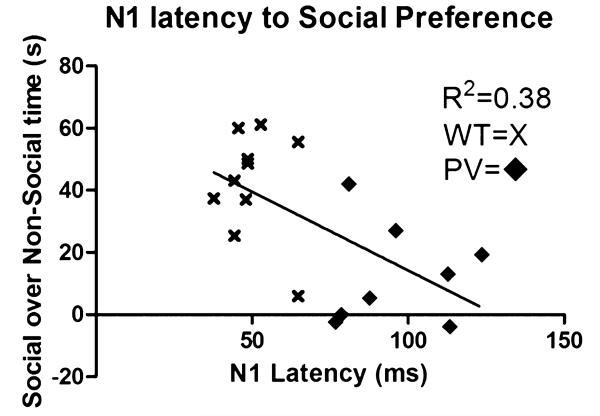

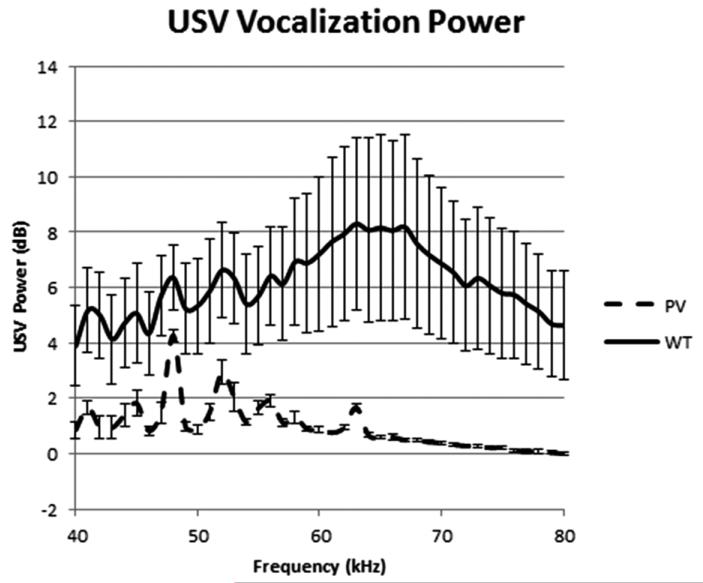

The PV-selective NR1 KO mice showed a significant delay in N1 latency compared with WT mice (Fig. 1, P < 0.001). There was a qualitative but nonsignificant increase in N1 amplitude in the PV-selective NR1 KO compared with WT mice (Fig. 2). The PV-selective NR1 KO mice showed significantly reduced sociability compared with WT mice (Fig. 3, P < 0.01). The PV-selective NR1 KO mice showed reduced premating USV power compared with WT mice (Figs. 4-6, P < 0.05). There was no difference between T-maze results for the two groups of subjects (Fig. 7). There was a significant correlation between N1 latency and sociability across all mice (Fig. 8 R2 = 0.38 and P < 0.05) but not between N1 latency and USV or T-maze measures (data not shown). There were no significant alterations for amplitude or latency of the P20 ERP component in PV-selective NR1 KO mice (P > 0.05 for both measures, data not shown).

Figure 1.

Effect of parvalbumin (PV)-selective NR1 knockout on N1 latency. PV-selective NR1 KO mice exhibit significantly delayed N1 latencies compared with wild-type (WT) mice. N1 latency delay is a robust marker of autism, and combined with sociability-specific deficits, indicates these mice have a constellation of autism-like phenotypes. Figures show the mean + SEM (Standard Error of the mean). (*** P < 0.001).

Figure 2.

The effect of parvalbumin (PV)-selective NR1 knockout on N1 event-related potential amplitude. (A) PV-selective NR1 KO mice had qualitatively but nonsignificantly increased N1 amplitude compared with wild-type (WT) mice. (B) Average waveforms are shown for PV-selective NR1 KO and WT mice. Figures show the mean + SEM.

Figure 3.

Effect of parvalbumin (PV)-selective NR1 knockout on sociability. In a two-cylinder social task, PV-selective NR1 KO mice showed significantly reduced preference for the social cylinder compared with wild-type (WT) mice. This indicates a reduction in sociability for the PV-selective NR1 KO mice compared with WT. Figures show the mean + SEM. (** P < 0.01).

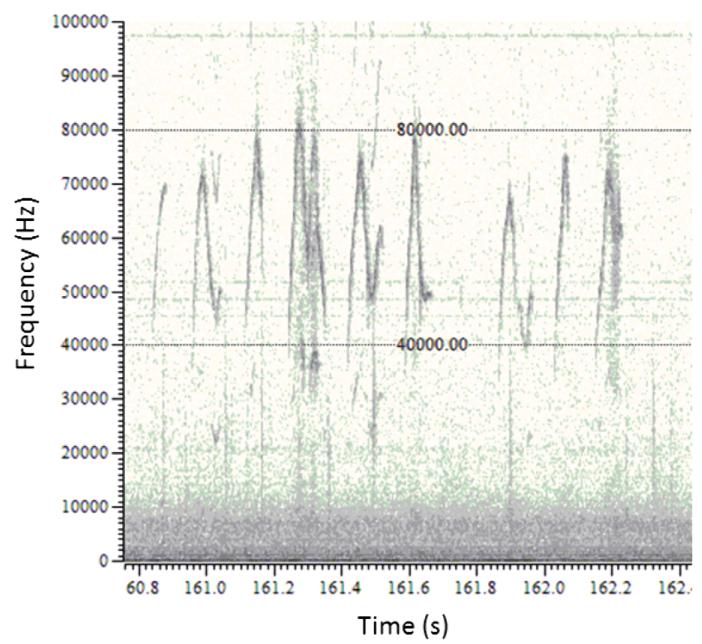

Figure 4.

Example raw data for premating vocalizations. Example demonstrates spectrograms of calls for analysis of call frequency range.

Figure 6.

Effect of parvalbumin (PV)-selective NR1 knockout on ultrasonic vocalization (USV) premating call power. PV-selective NR1 KO mice showed significantly reduced premating USVs in the presence of female mice as compared with wild-type (WT) mice. This indicates that in both nonmating (Fig. 2) and mating scenarios, PV-selective NR1 KO mice show reduced social interaction phenotypes compared with WT mice. Figures show the mean + SEM. (* P < 0.05).

Figure 7.

Effect of parvalbumin (PV)-selective NR1 knockout on T-maze task performance. Wild-type (WT) and PV-selective NR1 KO mice showed similar T-maze performance, indicating a lack of cognitive deficits. This indicates that alterations in n-methyl-d-aspartic acid receptor (NMDAR) expression on PV interneurons do not lead to reductions in working memory. Figures show the mean + SEM.

Figure 8.

Correlation between N1 latency and sociability among all mice. The combined parvalbumin (PV)-selective NR1 KO and wild-type (WT) groups show a correlation between N1 latency and social time (R2 = 0.38, P < 0.05). This supports the hypothesis that N1 latency is a possible marker for sociability and the severity of autism symptoms. Furthermore, combined with selective social deficits and autism-specific electrophysiological changes, this supports the PV interneuron n-methyl-d-aspartic acid receptor (NMDAR) knockout mouse as a model for autism.

Discussion

The current study demonstrates that the N1 latency, sociability, and premating USV changes present in the PV-selective NR1 KO model mimic the phenotypes present in ASD. N1 latency delays matched those found in ASD MEG studies which in turn were able to discriminate between patients and controls [Gandal et al. 2010; Roberts et al. 2010]. It also builds on previous mouse studies because it works on a specific pathway rather than inducing an environmental insult, such as prenatal exposure to valproic acid [Gandal et al. 2010]. Latency alterations in the PV-selective NR1 KO mice was specific to the N1, with no latency changes observed for the P1 component, also similar to findings in ASD. Additionally PV-selective NR1 KO mice showed selective behavioral deficits in nonmating social interactions and mating vocalizations without working memory deficits. Furthermore, there was a correlation between N1 latency and sociability, providing possible evidence of N1 latency as a biomarker for sociability.

Integration of sensory and social function

The N1 latency delays in the current model of ASD could become an important translational biomarker, with evidence that circuits that control N1 latency are also utilized in control or initiation of social interactions. The relationship between N1 latency and social function present in mice with selective deficits in NMDAR-mediated signaling on PV interneurons could also provide insight into possible neural circuits involved with social function. As such, EEG measures could potentially provide biomarkers that quantify the degree of impairment in neural circuits that control social behavior along with providing more focused guidance for treatment development [Gandal et al. 2010; Roberts et al. 2010]. Subsequent studies will determine whether normalization of N1 latency relates to increased social function. If there is evidence for N1 normalization coinciding with normalization of social function, N1 could provide a continuous biomarker for examining the severity of social deficits. However, if evidence indicates that it is only associated with the degree of initial impairment, then it may still be useful as an early diagnostic guide for disease classification and initial treatment course in prelanguage toddlers. In either case, EEG can be recorded early to compare normal development patterns to determine whether language impairment will occur. This is useful because early consistent intervention may result in better outcomes and reduced disability [Dawson, 2008].

Consistency with previous literature

Data from the current study share similarities and differences with previous reports related to NMDAR function on gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA)-ergic interneurons. One study by Carlen utilized similar mice with a PV-selective reduction in NR1. Additionally, a study by Belforte employed a different model in which NR1 was nonselectively removed from all types of GABAergic interneurons using a Ppp1r2 promoter rather than a cre-lox-driven PV-selective target. Table I illustrates that there is inconsistent evidence for schizophrenia-like phenotypes across the three reports. For instance, Carlen reports normal PPI and locomotor activity, which is inconsistent with psychosis-related behaviors. However, Belforte found deficits in both PPI and locomotor activity, supporting the presence of such symptoms in their model. For the cognitive domain, the findings from the three studies are also inconsistent. Carlen tested several different cognitive tasks and report deficits in some but not all measures. It is important to note that we did not reproduce the result obtained for one of the cognitive tasks used by Carlen. This may be due to differences in design, such that mice in the previous study were food deprived while those in the current study were not. This may add a dimension of motivation to the previous study that was not assessed presently. Similarly, Belforte also report cognitive impairment in their mice, suggesting that such deficits may involve a broader array of GABAergic populations. A consistent finding across Belforte’s and our study are the deficits in social interactions among the transgenic mice. As such, we propose that PV-selective loss of NR1 may be most relevant to the endophenotype of social dysfunction.

Table I. Comparison of Outcomes and Measures among Studies of NR1 Reduction.

| Carlen et al. [2011] | Belforte et al. | Saunders et al. | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Oscilllatory activity ERPs | Gamma power → Not assessed |

Notassessed Notassessed |

Notassessed N1 latency ↑ N1 amplitude → |

| Social behaviorand communication | Notassessed | Nest building ↓ Mating ↓ |

Social preference ↓ USV ↓ |

| Cognitive | T-maze (1 sec) ↓ Fear conditioning ↓ Water maze → |

Y-maze ↓ | T-maze (1 sec) → |

| Psychosis | LMA → PPI → |

LMA ↑ PPI ↓ |

LMA → |

ERP, event-related potential;USV, ultrasonic vocalization;LMA, Locomotor Activity;PPI, prepulse inhibition.

Interpretation of alterations in USVs

The current study identifies reductions in premating vocalizations among PV-selective NR1 KO mice, suggesting deficits in verbal communication that are related to a particular social situation. It is important to note that vocalizations in mice are not necessarily a surrogate for language per se. For example, neonatal distress calls are likely more akin to crying or screaming than talking. As such, they are a primitive form of verbal communication, albeit lacking the complexity of language. The current study evaluated premating vocalizations, which require a more complex pattern of vocal communication that is a specific type of social interaction, and which is associated with particular behaviors both on the part of the mouse that produces them (e.g. mounting) and the recipient (e.g. being receptive to mounting). As such, we propose that adult premating vocalizations move iteratively closer to the concept of language deficits that are relevant to ASD.

Implications for cognitive function

The current study does not provide direct evidence that NMDAR signaling on PV interneurons impact cognitive function. While there is a qualitative reduction in T-maze performance for the PV-selective KO mice, the variance in these subjects results in a statistically similar performance. This may suggest that the current study lacked sufficient power to detect mild cognitive deficits in PV-selective NR1 KO mice. However, the sample size was sufficient to detect social deficits, suggesting a relatively selective deficit in this domain. Therefore, this work advances our understanding of autisms and suggests that it may be a set of diseases with disrupted glutamate innervation of interneurons. Further, we propose that N1 latency has the potential to be an index of social function that may be used in the development of novel therapeutics.

Limitations and future directions

Some data suggest that NMDAR expression in PV neurons is developmentally regulated, with high levels of NMDAR present in immature PV neurons and with the level declining during postnatal development to a lower NMDAR level found in mature PV neurons. The progression of NMDAR downregulation may be relevant to the development of autism. Whether this NMDAR reduction occurs early in life or during adulthood may be relevant to the development of the ASDs. The recombination due to expression of the PV-selective Cre recombinase in the current model precludes clear interpretation of developmental data prior to full removal of NR1 at approximately 6-8 weeks of age [Carlen et al. 2011]. In addition, future studies could perform large longitudinal analyses to determine the overall prevalence of developmental EEG changes in ASD, along with understanding the progression of the EEG latency changes in order to create a robust diagnostic tool.

Figure 5.

Ultrasonic vocalization (USV) spectrum. Parvalbumin (PV)-selective NR1 KO mice showed significantly reduced mating USVs in the presence of female mice as compared with wild-type (WT) mice.

Acknowledgments

The study was supported by 5R01DA023210-02 (SJS). Dr. Roberts thanks the Oberkircher Family for the Oberkircher Family Endowed Chair in Pediatric Radiology. Steven Siegel reports having received grant support from Eli Lilly, AstraZeneca, NuPathe, and Pfizer that is unrelated to the content of this paper and consulting payments from NuPathe, Merck, Sanofi, and Wyeth that are unrelated to this work. Dr. Roberts is a consultant for prism clinical imaging. All other authors report no biomedical financial interests or potential conflicts of interest.

Grant sponsor: NIMH; Grant number: 5R01DA023210-02 (SJS).

Grant sponsor: Oberkircher Family; Grant number: Oberkircher Family Endowed Chair in Pediatric Radiology (TPR).

References

- Amann LC, Gandal MJ, Halene TB, Ehrlichman RS, White SL, et al. Mouse behavioral endophenotypes for schizophrenia. Brain Research Bulletin. 2010;83:147–161. doi: 10.1016/j.brainresbull.2010.04.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bangash MA, Park JM, Melnikova T, Wang D, Jeon SK, et al. Enhanced polyubiquitination of Shank3 and NMDA receptor in a mouse model of autism. Cell. 2011;145:758–772. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.03.052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- Belforte JE,, Zsiros V, Sklar ER, Jiang Z,, Yu G, et al. Postnatal NMDA receptor ablation in corticolimbic interneurons confers schizophrenia-like phenotypes. Nat Neurosci. 2010;13:76–83. doi: 10.1038/nn.2447. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carlen M, Meletis K, Siegle JH, Cardin JA, Futai K, et al. A critical role for NMDA receptors in parvalbumin interneurons for gamma rhythm induction and behavior. Molecular Psychiatry. 2012;17:537–548. doi: 10.1038/mp.2011.31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dawson G. Early behavioral intervention, brain plasticity, and the prevention of autism spectrum disorder. Development and Psychopathology. 2008;20:775–803. doi: 10.1017/S0954579408000370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deacon RM, Rawlins JN. T-maze alternation in the rodent. Nature Protocols. 2006;1:7–12. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2006.2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dinstein I, Pierce K, Eyler L, Solso S, Malach R, et al. Disrupted neural synchronization in toddlers with autism. Neuron. 2011;70:1218–1225. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2011.04.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edgar JC, Keller J, Heller W, Miller GA. Psychophysiology in research on psychopathology. Handbook of Psychophysiology. 3rd Edition. Cambridge University Press; New York: 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Ehrlichman RS, Gandal MJ, Maxwell CR, Lazarewicz MT, Finkel LH, et al. N-methyl-d-aspartic acid receptor antagonist-induced frequency oscillations in mice recreate pattern of electrophysiological deficits in schizophrenia. Neuroscience. 2009;158:705–712. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2008.10.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ehrlichman RS, Luminais SN, White SL, Rudnick ND, Ma N, et al. Neuregulin 1 transgenic mice display reduced mismatch negativity, contextual fear conditioning and social interactions. Brain Research. 2009;1294:116–127. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2009.07.065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gandal MJ, Edgar JC, Ehrlichman RS, Mehta M, Roberts TP, Siegel SJ. Validating gamma oscillations and delayed auditory responses as translational biomarkers of autism. Biological Psychiatry. 2010;68:1100–1106. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2010.09.031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gandal MJ, Ehrlichman RS, Rudnick ND, Siegel SJ. A novel electrophysiological model of chemotherapy-induced cognitive impairments in mice. Neuroscience. 2008;157:95–104. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2008.08.060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gandal MJ, Nesbitt AM, McCurdy RM, Alter MD. Measuring the maturity of the fast-spiking interneuron transcriptional program in autism, schizophrenia, and bipolar disorder. PLoS ONE. 2012;7:e41215. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0041215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gogolla N, Leblanc JJ, Quast KB, Sudhof TC, Fagiolini M, Hensch TK. Common circuit defect of excitatory-inhibitory balance in mouse models of autism. Journal of neurodevelopmental disorders. 2009;1:172–181. doi: 10.1007/s11689-009-9023-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gonzalez-Burgos G, Lewis DA. NMDA Receptor Hypofunction, Parvalbumin-Positive Neurons and Cortical Gamma Oscillations in Schizophrenia. Schizophrenia bulletin. 2012 doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbs010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gourbal BE, Barthelemy M, Petit G, Gabrion C. Spectrographic analysis of the ultrasonic vocalisations of adult male and female BALB/c mice. Naturwissenschaften. 2004;91:381–385. doi: 10.1007/s00114-004-0543-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halene TB, Ehrlichman RS, Liang Y, Christian EP, Jonak GJ, et al. Assessment of NMDA receptor NR1 subunit hypofunction in mice as a model for schizophrenia. Genes, Brain, and Behavior. 2009;8:661–675. doi: 10.1111/j.1601-183X.2009.00504.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanlon FM, Miller GA, Thoma RJ, Irwin J, Jones A, et al. Distinct M50 and M100 auditory gating deficits in schizophrenia. Psychophysiology. 2005;42:417–427. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8986.2005.00299.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jamain S, Radyushkin K, Hammerschmidt K, Granon S, Boretius S, et al. Reduced social interaction and ultrasonic communication in a mouse model of monogenic heritable autism. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2008;105:1710–1715. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0711555105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Javitt DC, Jayachandra M, Lindsley RW, Specht CM, Schroeder CE. Schizophrenia-like deficits in auditory P1 and N1 refractoriness induced by the psychomimetic agent phencyclidine (PCP) Clinical Neurophysiology. 2000;111:833–836. doi: 10.1016/s1388-2457(99)00313-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lawrence YA, Kemper TL, Bauman ML, Blatt GJ. Parvalbumin-, calbindin-, and calretinin-immunoreactive hippocampal interneuron density in autism. Acta Neurologica Scandinavica. 2010;121:99–108. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0404.2009.01234.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maggio JC, Whitney G. Ultrasonic vocalizing by adult female mice (Mus musculus) Journal of Comparative Psychology. 1985;99:420–436. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mazhari S, Price G, Waters F, Dragovic M, Jablensky A. Evidence of abnormalities in mid-latency auditory evoked responses (MLAER) in cognitive subtypes of patients with schizophrenia. Psychiatry Research. 2011;187:317–323. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2011.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oram Cardy JE, Flagg EJ, Roberts W, Roberts TP. Auditory evoked fields predict language ability and impairment in children. International Journal of Psychophysiology. 2008;68:170–175. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpsycho.2007.10.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ricceri L, Moles A, Crawley J. Behavioral phenotyping of mouse models of neurodevelopmental disorders: relevant social behavior patterns across the life span. Behavioural Brain Research. 2007;176:40–52. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2006.08.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roberts TP, Cannon KM, Tavabi K, Blaskey L, Khan SY, et al. Auditory magnetic mismatch field latency: a biomarker for language impairment in autism. Biological Psychiatry. 2011;70:263–269. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2011.01.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roberts TP, Khan SY, Rey M, Monroe JF, Cannon K, et al. MEG detection of delayed auditory evoked responses in autism spectrum disorders: towards an imaging biomarker for autism. Autism Research. 2010;3:8–18. doi: 10.1002/aur.111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rojas DC, Maharajh K, Teale P, Rogers SJ. Reduced neural synchronization of gamma-band MEG oscillations in first-degree relatives of children with autism. BMC Psychiatry. 2008;8:66. doi: 10.1186/1471-244X-8-66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rojas DC, Teale PD, Maharajh K, Kronberg E, Youngpeter K, et al. Transient and steady-state auditory gamma-band responses in first-degree relatives of people with autism spectrum disorder. Molecular Autism. 2011;2:11. doi: 10.1186/2040-2392-2-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scattoni ML, Crawley J, Ricceri L. Ultrasonic vocalizations: A tool for behavioural phenotyping of mouse models of neurodevelopmental disorders. Neuroscience and Biobehavioral Reviews. 2009;33:508–515. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2008.08.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siegel SJ, Connolly P, Liang Y, Lenox RH, Gur RE, et al. Effects of strain, novelty, and NMDA blockade on auditory-evoked potentials in mice. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2003;28:675–682. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1300087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sohal VS, Zhang F, Yizhar O, Deisseroth K. Parvalbumin neurons and gamma rhythms enhance cortical circuit performance. Nature. 2009;459:698–702. doi: 10.1038/nature07991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Umbricht D, Vyssotky D, Latanov A, Nitsch R, Brambilla R, et al. Midlatency auditory event-related potentials in mice: comparison to midlatency auditory ERPs in humans. Brain Research. 2004;1019:189–200. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2004.05.097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White NR, Prasad M, Barfield RJ, Nyby JG. 40- and 70-kHz vocalizations of mice (Mus musculus) during copulation. Physiology and Behavior. 1998;63:467–473. doi: 10.1016/s0031-9384(97)00484-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]