Abstract

Purpose:

The purpose of the following study is to compare short wave automated perimetry (SWAP) versus standard automated perimetry (SAP) for early detection of diabetic retinopathy (DR).

Materials and Methods:

A total of 40 diabetic patients, divided into group I without DR (20 patients = 40 eyes) and group II with mild non-proliferative DR (20 patients = 40 eyes) were included. They were tested with central 24-2 threshold test with both shortwave and SAP to compare sensitivity values and local visual field indices in both of them. A total of 20 healthy age and gender matched subjects were assessed as a control group.

Results:

Control group showed no differences between SWAP and SAP regarding mean deviation (MD), corrected pattern standard deviation (CPSD) or short fluctuations (SF). In group I, MD showed significant more deflection in SWAP (−4.44 ± 2.02 dB) compared to SAP (−0.96 ± 1.81 dB) (P =0.000002). However, CPSD and SF were not different between SWAP and SAP. In group II, MD and SF showed significantly different values in SWAP (−5.75 ± 3.11 dB and 2.0 ± 0.95) compared to SAP (−3.91 ± 2.87 dB and 2.86 ± 1.23) (P =0.01 and 0.006 respectively). There are no differences regarding CPSD between SWAP and SAP. The SWAP technique was significantly more sensitive than SAP in patients without retinopathy (p), but no difference exists between the two techniques in patients with non-proliferative DR.

Conclusion:

The SWAP technique has a higher yield and efficacy to pick up abnormal findings in diabetic patients without overt retinopathy rather than patients with clinical retinopathy.

Keywords: Mean deviation, non-proliferative diabetic retinopathy, short fluctuations, short wave automated perimetry, standard automated perimetry

Diabetic retinopathy (DR) is one of the most common causes of blindness all over the world.[1] The retinal neurosensory losses sometimes precede the onset of clinically detectable retinopathy.[2] The Progression of at least some of visual deficit parallels the development of DR.[3]

Several studies have shown that DR may influence the visual field; such changes are clear at advanced stages of the disease.[4,5,6] A variable amount of visual field loss is often found in DR and the extent of the loss depends on the severity of the illness.[7,8]

In a study by Wisznia et al.[9] studied the visual field in the form of partial depression of the central isopters in diabetic patients with non-proliferative DR, all diabetic eyes with retinopathy showed central visual field defects and about half the diabetic patients without retinopathy also had visual field defects, but no visual field defects were found in the control group.

Blue on yellow perimetry known as shortwave length automated perimetry (SWAP) represents recent and existing advance in early identification of ischemic change in diabetes, it differs from standard automated perimetry (SAP) only in that carefully chosen wavelength of blue light is used as the stimulus and specific color and brightness of yellow light is used for background illumination, SWAP is considered an earlier indicator of function loss in ischemic change in DR than SAP. SWAP has been shown to yield more extensive visual field loss than SAP in diabetic changes. This may be based on finding of Wild,[10] that the blue cone is more susceptible to damage in diabetes.

SWAP is a functional test to detect visual field abnormality in patients at high risk of developing DR where white on white (SAP) still within normal.[11]

Recently, Bengtsson et al.[12] described the correlation between peripheral retinopathy, excluding the fovea and perimetry using both SAP and SWAP. They showed that perimetric threshold sensitivities decreased with increasing severity of retinopathy as documented by stereo fundus photographs, graded according to the early treatment diabetic retinopathy study (ETDRS) severity scale.[13] This correlation was significant for both SAP and SWAP, suggesting that perimetry can be useful for monitoring visual function in patients with diabetes. Although Lutze and Bresnick[14] found no overall sensitivity loss compared with normal, significant sensitivity reduction and localized defects were detected with more severe DR.

Aim of the work

To investigate the value of SWAP-blue on yellow compared with SAP in detecting changes in the retinal sensitivity of the visual field in diabetic patients with or without retinopathy.

Materials and Methods

This cross-sectional clinical study was conducted between April 2009 and March 2010. All subjects were chosen among patients attending the Ophthalmology Out-patient Clinic. It included 40 patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus (DM), their ages ranged from 37 to 65 years old. They were 10 males and 30 females. 20 healthy subjects were assessed as a control group. Their age range (42-62 years) and female/male ratio (7/3) were matching with the patients group. Patients group was subdivided into:

Group 1: 20 diabetics patients (40 eyes) without DR, their ages ranged between 43 and 65 years

Group 2: 20 diabetics patients (40 eyes) with early DR, their ages ranged between 37 and 65 years

Group 3: 20 healthy subjects (40 eyes) were assessed as a control group, their age ranged between 42 and 62 years.

The study excluded those who had a history of glaucoma, opaque media and patients with corrected visual acuity (VA) less than 0.5 and patients who received retinal laser therapy.

After approval of the local ethical committee (Institutional Reviewing Board of Ophthalmology Department, Ain Shams University Hospitals), informed consents were taken from patients and controls.

All included patients were subjected to history taking focusing on age, gender and duration of diabetes.

Ophthalmologic evaluation included full assessment with particular emphasis on VA measurement, intraocular pressure (IOP) measurements, slit lamp examination to assess anterior segment and fundus examination.

Oculus Twinfield was used to obtain visual field sensitivities. (Twinfield is a full field projection perimeter that offers both static and kinetic testing, either automatic or manual, permitting examinations in accordance with the Goldmann standard). The threshold program central 24-2 was used, begin with white on white (SAP) followed by blue on yellow perimetry (SWAP) and comparison of the result of both.

All patients attended for three visits. Only results from the second visit were analyzed, thereby minimizing learning effects for both perimetric paradigms.[15] Visit one was used to undertake refraction, VA and fundus examination and to perimetrically train patients (using SAP and SWAP program 24-2). Visit 2 for program 24-2 of SAP and Visit 3 for program 24-2 of SWAP to avoid patient fatigue.

Procedures

The patient's correction was adjusted for a viewing distance of 30 cm. SAP was performed with the Twinfield Analyzer (Oculus perimetry introduction guide), using (24-2, full-threshold) program. A size III stimulus was chosen, which projected onto a background illuminated bowl. SWAP was also performed using the program 24-2 with full-threshold performance. A size III light stimulus was chosen, with a 440-nm-wavelength blue spot projected onto a 530-nm-wavelength yellow background at a maximal brightness of 100 dc/m2.

The visual field charts were reviewed for mean deviation (MD), pattern standard deviation (SD), test reliability (fixation losses and false-positive and false-negative rates) and test time.

During the test, blind spot fixation was monitored. The reliability of each visual field test was assessed and the test was considered reliable only if fixation losses and false-positive and false-negative rates were less than 25%. Those exceeding 25% were considered unqualified and were excluded.

Statistical analysis

We conducted statistical analysis using the statistical package for the social sciences (SPSS software version 15, 233 South Wacker Drive, 11th Floor, Chicago, Illinois 60606-6307, U.S.A.). Quantitative variables were expressed as mean ± SD. Student's t-test was used to assess the statistical significance of differences between the different groups. Qualitative parameters were analyzed using Chi-square test. Regression analysis was performed to assess the different factors that can affect MD of both SAP and SWAP in the different groups.

Results

Age was not statistically different between the two patients groups and controls. However, it was slightly higher in group 2 with non-proliferative retinopathy than the 2 other groups. Gender was not different between the studied groups [Table 1].

Table 1.

Differences between group I and group II

Mean duration (mean ± SD) of DM in group 1 (6.70 ± 5.61 years) was significantly lower than in group 2 (10.05 ± 5.10 years) (P =0.03).

IOP was not statistically different between the three studied groups with P = (0.74, 0.91 and 0.66 respectively) [Table 1].

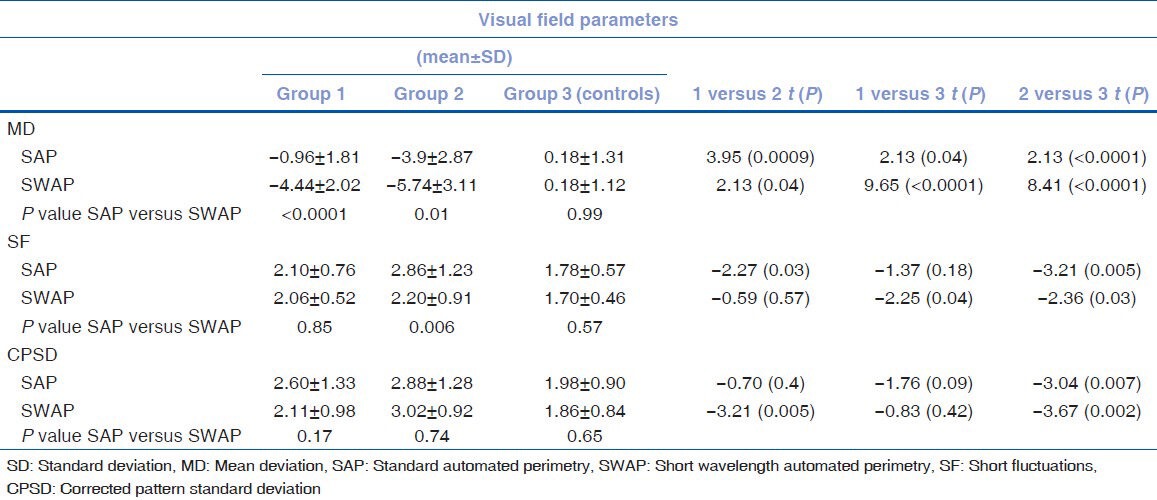

MD in SAP was significantly lower in group 2 than group 1 (P =0.009) and 3 (P =0.000009). Moreover, it was significantly lower in group 1 compared with group 3 (P =0.0001). Similar results were shown with MD of SWAP technique [Table 2].

Table 2.

Comparison of the 2 perimetric techniques parameters in the three studied groups

Corrected pattern standard deviation (CPSD) in SAP was statistically higher in group 2 compared to group 3 (P =0.007). No significant difference was noticed regarding this parameter neither between group 1 and 2 nor between group 1 and 3 [Table 2]. CPSD in SWAP showed the significantly higher results in group 2 compared with group 1 (P =0.005) and 3 (P =0.002). However, no difference was recorded between group 1 and group 3 [Table 2].

Short fluctuation (SF) in SAP was statistically higher in group 2 (2.86 ± 1.23) than in group 1 (P =0.03) and group 3 (P =0.005) (1.78 ± 0.57). However, it was not different between group 1 and group 3 [Table 2]. SF showed the same pattern of difference in SWAP between the studied three groups

In group 1, MD was significantly lower in SWAP compared with SAP (P =0.00002). On the other hand, CPSD and SF showed no significant difference between SAP and SWAP techniques [Table 2].

In group 2, MD and SF were significantly lower in SWAP compared to SAP (P =0.01 and 0.006 respectively). On the other hand, there was no difference regarding CPSD of SAP and SWAP [Table 2].

In the control group, no difference was detected regarding MD, CPSD and SF between SAP and SWAP techniques [Table 2].

Multiple regression analysis of factors related to MD of SWAP in the group 2 (with DR) showed significant relation between MD and glycated hemoglobin (Beta = 0.37).

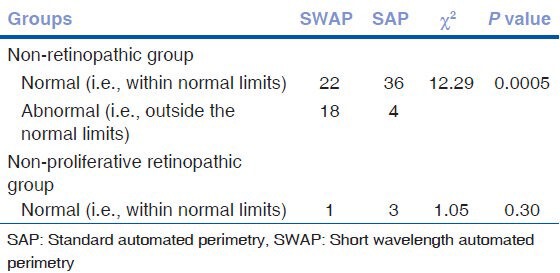

The SWAP technique showed significantly higher abnormal findings among patients with no clinical retinopathy compared to SAP technique (P =0.0005). However, both techniques were of similar sensitivity to pick up abnormal cases among patients with non-proliferative DR [Table 3].

Table 3.

Comparison of abnormality of SAP and SWAP techniques in the two studied diabetic groups

Discussion

The selected age range in the current study is consistent with findings of many authors.[16,17]

Gender ratio was not different between the 3 groups founding a good basis for comparison. Moreover, female preponderance was evident which is consistent with Macky et al.;[18] who found that the prevalence of DR was statistically significantly higher in females (22 vs. 17%, P < 0.05).

In the current study, the duration of diabetes was significantly longer in diabetic patients with non-proliferative retinopathy compared with those without retinopathy. DR needs longer duration to develop; the duration of diabetes is probably the strongest predictor for development and progression of retinopathy. Among younger-onset patients with diabetes in the Wisconsin Epidemiologic Study of DR, the prevalence of any retinopathy was 8% at 3 years, 25% at 5 years, 60% at 10 years and 80% at 15 years respectively.[1] Our findings are consistent with Macky et al.,[18] reported that the prevalence of DR was statistically significantly higher with longer diabetes disease duration (P < 0.001). Hohenstein et al.[17] found the mean duration of diabetes 12.9 years.

The degree of diabetic metabolic control as assessed by Hemoglobin A1c (HbA1c) was better in diabetic patients without retinopathy compared with those with non-proliferative DR. The United Kingdom Prospective Diabetes Study Stratton et al.[19] found that good blood sugar control does reduce the risk of DR as well as does reduce the progression of retinopathy.[18] The diabetes control and complications trial,[20] diabetic retinopathy study (DRS) and ETDRS[20] also support that good glycogenic control is important in the early stage of diabetes and helps in delaying the onset of retinopathy and halting the rate of progression.

In the current study, we demonstrated that parameters of SWAP technique yielded results that were significantly different than the SAP one regardless the presence of DR. This may reflect the sensitivity of SWAP technique. Previous studies have reported short-wavelength sensitivity to be affected earlier than achromatic sensitivity early in the course of DR.[21,22,23,24] More recently according to[25,26,27,28] who found that SWAP is a perimetric test designed to isolate and quantify the activity of short-wavelength-sensitive pathways.

Parameters of both techniques showed a significant difference between group 1 and 2 with more affection in the group with non-proliferative DR than those without DR. However, both methods demonstrated significantly different values in diabetics from controls. Abrishami et al.,[29] found that there is significant differences between diabetic group and the control group regarding MD, mean corrected sensitivity and mean corrected total deviation.

Considering the whole array of parameters in both techniques that define the abnormal results, it was clear that SWAP is more sensitive than SAP in picking up more abnormalities in diabetic patients without retinopathy (χ2 = 12.29 and P = 0.0005). In diabetic patients with non-proliferative retinopathy the two techniques showed similar sensitivity to pick up abnormal cases. This means that SWAP being more sensitive tool is capable to detect minor changes in patients without clinical overt retinopathy than the less sensitive too. However, in overt cases with non-proliferative retinopathy, changes are marked so that both techniques were capable to show, equally, the visual field changes.

Our results are in agreement with Remky et al.[30] who found that sensitivity is significantly lower in patients with diabetes than in controls. SWAP thresholds were significantly more greatly reduced by diabetes than those of white-on-white perimetry (P =0.003).

Han et al.,[31] found that SWAP is a sensitive measurement of diabetic dysfunction, even prior to retinopathy.

In type 1 DM, Abrishami et al.[29] reported that MD in patients was-6.51 dB and in the control group-3.0 dB; the difference was statistically significant.

In the current study, diabetic control represented by level of HbA1c was the only parameter that affects the MD of SWAP in diabetic patients. Other parameters as duration of diabetes and gender were not of significant impact as analyzed by the multiple regression tests.

We can conclude that perimetry is a useful tool in assessment of the retina of diabetic patients. SWAP technique is better than SAP in this regards especially when overt clinical features of DR are yet lacking.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Costs were the responsibility of the authors and instruments used in the study belong to Faculty of Medicine, a part of Ain Shams University, which is a public governmental organization.

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

References

- 1.Klein R, Klein BE, Moss SE. Visual impairment in diabetes. Ophthalmology. 1984;91:1–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Roy MS, Rick ME, Higgins KE, McCulloch JC. Retinal cotton-wool spots: An early finding in diabetic retinopathy? Br J Ophthalmol. 1986;70:772–8. doi: 10.1136/bjo.70.10.772. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Arden GB, Hamilton AM, Wilson-Holt J, Ryan S, Yudkin JS, Kurtz A. Pattern electroretinograms become abnormal when background diabetic retinopathy deteriorates to a preproliferative stage: Possible use as a screening test. Br J Ophthalmol. 1986;70:330–5. doi: 10.1136/bjo.70.5.330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Greite JH, Zumbansen HP, Adamczyk R. Visual field in diabetic retinopathy. Doc Ophthalmol Proc Ser. 1980;26:25–32. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bek T, Lund-Andersen H. Accurate superimposition of perimetry data onto fundus photographs. Acta Ophthalmol (Copenh) 1990;68:11–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1755-3768.1990.tb01642.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chee CK, Flanagan DW. Visual field loss with capillary non-perfusion in preproliferative and early proliferative diabetic retinopathy. Br J Ophthalmol. 1993;77:726–30. doi: 10.1136/bjo.77.11.726. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Buckley S, Jenkins L, Benjamin L. Field loss after pan retinal photocoagulation with diode and argon lasers. Doc Ophthalmol. 1992;82:317–22. doi: 10.1007/BF00161019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Khosla PK, Gupta V, Tewari HK, Kumar A. Automated perimetric changes following panretinal photocoagulation in diabetic retinopathy. Ophthalmic Surg. 1993;24:256–61. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wisznia KI, Lieberman TW, Leopold IH. Visual fields in diabetic retinopathy. Br J Ophthalmol. 1971;55:183–8. doi: 10.1136/bjo.55.3.183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wild JM. Short wavelength automated perimetry. Acta Ophthalmol Scand. 2001;79:546–59. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0420.2001.790602.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Demirel S, Johnson CA. Short wavelength automated perimetry (SWAP) in ophthalmic practice. J Am Optom Assoc. 1996;67:451–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bengtsson B, Heijl A, Agardh E. Visual fields correlate better than visual acuity to severity of diabetic retinopathy. Diabetologia. 2005;48:2494–500. doi: 10.1007/s00125-005-0001-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fundus photographic risk factors for progression of diabetic retinopathy. ETDRS report number 12. Early Treatment Diabetic Retinopathy Study Research Group. Ophthalmology. 1991;98:823–33. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lutze M, Bresnick GH. Lens-corrected visual field sensitivity and diabetes. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1994;35:649–55. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Heijl A, Bengtsson B. The effect of perimetric experience in patients with glaucoma. Arch Ophthalmol. 1996;114:19–22. doi: 10.1001/archopht.1996.01100130017003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Park CY, Park SE, Bae JC, Kim WJ, Park SW, Ha MM, et al. Prevalence of and risk factors for diabetic retinopathy in Koreans with type II diabetes: Baseline characteristics of Seoul Metropolitan City-Diabetes Prevention Program (SMC-DPP) participants. Br J Ophthalmol. 2012;96:151–5. doi: 10.1136/bjo.2010.198275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hohenstein B, Hugo CP, Hausknecht B, Boehmer KP, Riess RH, Schmieder RE. Analysis of NO-synthase expression and clinical risk factors in human diabetic nephropathy. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2008 Apr;23:1346–54. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfm797. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Macky TA, Khater N, Al-Zamil MA, El Fishawy H, Soliman MM. Epidemiology of diabetic retinopathy in Egypt: A hospital-based study. Ophthalmic Res. 2011;45:73–8. doi: 10.1159/000314876. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Stratton IM, Kohner EM, Aldington SJ, Turner RC, Holman RR, Manley SE, et al. UKPDS 50: Risk factors for incidence and progression of retinopathy in Type II diabetes over 6 years from diagnosis. Diabetologia. 2001;44:156–63. doi: 10.1007/s001250051594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chew EY, Benson WE, Boldt CH, Chang TS, Lobes LA, Jr, Miller JW, et al. American Academy of Ophthalmologist (AAO) Diabetic Retinopathy. 2003. Available from: http://www.bms.brown.edu/surgery/ophthalmology/resident/Exams/documents/PPPDiabeticRetinopathy.pdf .

- 21.Greenstein VC, Hood DC, Ritch R, Steinberger D, Carr RE. S (blue) cone pathway vulnerability in retinitis pigmentosa, diabetes and glaucoma. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1989;30:1732–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lobefalo L, Verrotti A, Mastropasqua L, Della Loggia G, Cherubini V, Morgese G, et al. Blue-on-yellow and achromatic perimetry in diabetic children without retinopathy. Diabetes Care. 1998;21:2003–6. doi: 10.2337/diacare.21.11.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Nomura R, Terasaki H, Hirose H, Miyake Y. Blue-on-yellow perimetry to evaluate S cone sensitivity in diabetics. Ophthalmic Res. 2000;32:69–72. doi: 10.1159/000055592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Afrashi F, Erakgün T, Köse S, Ardiç K, Menteº J. Blue-on-yellow perimetry versus achromatic perimetry in type 1 diabetes patients without retinopathy. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2003;61:7–11. doi: 10.1016/s0168-8227(03)00082-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sample PA, Boynton RM, Weinreb RN. Isolating the color vision loss in primary open-angle glaucoma. Am J Ophthalmol. 1988;106:686–91. doi: 10.1016/0002-9394(88)90701-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Johnson CA. Diagnostic value of short-wavelength automated perimetry. Curr Opin Ophthalmol. 1996;7:54–8. doi: 10.1097/00055735-199604000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Polo V, Pinilla I, Abecia E, Larrosa JM, Pablo LE, Honrubia FM. Assessment of the ocular media absorption index. Int Ophthalmol. 1996;20:7–9. doi: 10.1007/BF00212937. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Johnson CA, Adams AJ, Casson EJ, Brandt JD. Blue-on-yellow perimetry can predict the development of glaucomatous visual field loss. Arch Ophthalmol. 1993;111:645–50. doi: 10.1001/archopht.1993.01090050079034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Abrishami M, Daneshvar R, Yaghubi Z. Short-wavelength automated perimetry in type I diabetic patients without retinal involvement: A test modification to decrease test duration. Eur J Ophthalmol. 2012;22:203–9. doi: 10.5301/EJO.2011.8364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Remky A, Weber A, Hendricks S, Lichtenberg K, Arend O. Short-wavelength automated perimetry in patients with diabetes mellitus without macular edema. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2003;241:468–71. doi: 10.1007/s00417-003-0666-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Han Y, Adams AJ, Bearse MA, Jr, Schneck ME. Multifocal electroretinogram and short-wavelength automated perimetry measures in diabetic eyes with little or no retinopathy. Arch Ophthalmol. 2004;122:1809–15. doi: 10.1001/archopht.122.12.1809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]