Abstract

Introduction

Familial breast cancer (fBC) is generally associated with an early age of diagnosis and a higher frequency of disease among family members. Over the past two decades a number of genes have been identified that are unequivocally associated with breast cancer (BC) risk but there remain a significant proportion of families that cannot be accounted for by these genes. Copy number variants (CNVs) are a form of genetic variation yet to be fully explored for their contribution to fBC. CNVs exert their effects by either being associated with whole or partial gene deletions or duplications and by interrupting epigenetic patterning thereby contributing to disease development. CNV analysis can also be used to identify new genes and loci which may be associated with disease risk.

Methods

The Affymetrix Cytogenetic Whole Genome 2.7 M (Cyto2.7 M) arrays were used to detect regions of genomic re-arrangement in a cohort of 129 fBC BRCA1/BRCA2 mutation negative patients with a young age of diagnosis (<50 years) compared to 40 unaffected healthy controls (>55 years of age).

Results

CNV analysis revealed the presence of 275 unique rearrangements that were not present in the control population suggestive of their involvement in BC risk. Several CNVs were found that have been previously reported as BC susceptibility genes. This included CNVs in RPA3, NBN (NBS1), MRE11A and CYP19A1 in five unrelated fBC patients suggesting that these genes are involved in BC initiation and/or progression. Of special interest was the identification of WWOX and FHIT rearrangements in three unrelated fBC patients.

Conclusions

This study has identified a number of CNVs that potentially contribute to BC initiation and/or progression. The identification of CNVs that are associated with known tumour suppressor genes is of special interest that warrants further larger studies to understand their precise role in fBC.

Keywords: Breast cancer, DNA repair, CNV

Introduction

Global cancer statistics identify BC as the most frequently diagnosed cancer (23%) and leading cause of cancer related death (14%) in females [1]. Nearly 27% of these BCs occur in a familial setting typically associated with an earlier age of disease diagnosis and a higher frequency among family members and is termed fBC [2,3]. It is estimated that 5-10% of these families harbor germline mutations or complex genomic changes that render inactive one of four high penetrance genes (BRCA1, BRCA2, TP53 or PTEN) or moderate penetrance genes (CHEK2, ATM, BRIP1 and PALB2) [2,4,5]. Associations have also been identified for other genes in fBC including ATM, CASP8, CTLA4, NBN, CYP19A1, TERT, and XRCC3[6]. The most recent BC meta-analysis has identified 41 loci and suggests that over 1000 loci may be involved in disease susceptibility [7]. The identification of BRCA1 and BRCA2 as susceptibility genes for BC and the more recent addition of PALB2, BRIP1 and RAD51C[5] have focused attention on genes associated with double strand break repair (DSBR). There are at least 39 genes implicated in DSBR, all of which could potentially be associated with BC risk. This is analogous to DNA mismatch repair (MMR), where there are at least 21 genes associated with this process, of which four are now routinely assessed and more recently a fifth gene (POLD1) has been added to the list [8,9]. Despite the plethora of information regarding genetic loci associated with BC risk, for many fBC cases no genetic predisposition has been identified. Outside the context of gene mutations other mechanisms may be associated with disease development including gene silencing as a result of epigenetic re-programming of BC susceptibility genes (analogous to loss of EPCAM and the re-arrangement of the epigenetic profile on chromosome 2, rendering MSH2 inactive [10,11]), or mutations in genes not yet associated with a predisposition to disease.

One type of genetic alteration that could account for susceptibility is genetic re-arrangements detected as CNVs. CNVs represent a class of structural variation involving regions of duplication or deletion of genomic material that can encompass large stretches of genomic sequence ranging from megabases (Mbs) to a few kilobases (Kb) in size. As a consequence, CNVs can contribute to disease when they incorporate functional gene sequence (coding and promoter regions of genes) or exert more cryptic effects, that could affect epigenetic regulation (methylation, microRNA targets) and non-coding intronic gene sequences [12-23]. Two reports have recently examined CNVs in association with BRCA1/BRCA2 mutation negative fBC patients. The first of these has reported a greater abundance of rare CNVs in fBC patients and suggest that rare CNVs are likely to contain genetic factors associated with BC predisposition, while the second report associated several CNV markers with fBC risk and suggests their use in disease risk assessment [24,25].

The detection of CNVs has historically relied upon the use of DNA arrays, typically comprised of oligonucleotide markers distributed across the whole genome. The resolution of DNA arrays has increased to allow for the detection of genomic rearrangements as small as a few Kb in size. In this study we used the Affymetrix Cyto2.7 M array which provided the highest genomic coverage of any commercially available microarray at the time of assay to assess CNV variation in an fBC cohort. The Cyto2.7 M array contains a combination of 400,000 single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) and >2.1 million copy number probes (average spacing 1395 base pairs (bp)) which together can be used to accurately detect genomic rearrangements.

We conducted a patient-control analysis examining 129 fBC patients and 40 control subjects derived from the same population to identify CNVs which could be associated with the genetic basis of their disease. To date this study represents one of the largest CNV studies of BRCA1/BRCA2 mutation negative fBC patients.

Materials and methods

Samples

The study was approved by the University of Newcastle’s Human Research Ethics Committee and the Hunter New England Human Research Ethics Committee. Genomic DNAs were obtained from fBC patients who had given informed consent for their DNA to be used for studies into their disease and control DNA samples from the Hunter Community Study (HCS) [26]. DNA was extracted from whole blood by the salt precipitation method [27].

A cohort of 129 patients clinically diagnosed with early-onset fBC were used in this study. All patients had been diagnosed with BC and were the first individual (proband) of their family to seek genetic testing for mutations in BRCA1/BRCA2. Mutation screening was performed using Sanger Sequencing and Multiplex ligation-dependant probe amplification (MLPA) analysis. No mutations were identified in any of the patients (BRCA1/BRCA2 mutation negative). The average patient age was calculated to be <40.7 years. Genomic DNA from 40 controls [26] was also utilized in this study. These were healthy (cancer free) individuals aged >55 years at the time of sample collection.

Genomic array preparation and data processing

The genomic DNA from 129 fBC patients and 40 controls were processed on the Affymetrix Cyto2.7 M array consistent with manufacturer’s protocols. CEL files were analysed in Affymetrix, the Chromosome Analysis Suite (ChAS) (Version CytoB-N1.2.0.232; r4280) using NetAffx Build 30.2 (Hg18) annotation. Quality control (QC) parameters were optimized and validated using a training set of 20 randomly selected samples. All samples were subject to a series of quality cut-off measures: snpQC >1.1 (SNP probe QC based off distances between the distribution of alleles (AA, AB and BB) where larger differences are associated with an increased ability to differentiate genotype; default), mapdQC <0.27 (Median Absolute Pair-wise Difference; CN probe QC based off a reference model; default) and wavinessSd <0.1 (measure of standard deviation in data waviness; the GC content across the genome correlates with average probe intensities i.e. high GC probes are brighter than low GC probes on average, creating waves in the data). CNV regions were assessed according to call confidence, probe count, size and by visual inspection for distinction from normal CN state. Data was also visually inspected to identify regions with low density of markers (Additional file 1: Table S1) which were excluded across all samples. Most thresholds were more stringent than default settings alone in an aim to minimize false-positive CNVs being included in the analysis. CNV regions were filtered across all samples using the following parameters: >90% confidence, autosomes only and a minimum number of 24 probes. Using these parameters the limit of detection was 9.65 Kb across all samples used in the current study. This does not exclude the possibility of CNVs smaller than this from contributing to disease in a proportion of fBC patients.

CNV and statistical analysis

CNVs in fBC patients and controls were subject to a series of comprehensive analyses which included: (1) interrogation for CNVs residing in or ±100 Kb of 61 genes (associated with DSBR, MMR and BC susceptibility) and 41 SNPs recently reported to be associated with BC risk [6,7,28,29] (see Additional file 1: Tables S2 and S3); (2) comparison of CNVs between fBC patients and controls according to CN occurrence and distribution across the genome; (3) identification of rare CNVs using the Database of Genomic Variants (DGV); and (4) the identification of genes associated with malignancy (non-specific) using the Network of Cancer Genes (Version 3.0) and the Cancer Gene Census (CGC; 15 March 2012) databases [30,31]. Associations (e.g. numbers and sizes of CNVs) were statistically compared using a two tailed un-paired t-test Graphpad Prism (Version 6) [32].

Validation of CNV results

CNV results were validated using pre-designed TaqMan Copy Number (CN) Assays (Applied Biosystems). Up to two CN assays were selected within the CNV region indicated by the Cyto2.7 M array and CN assays, proximal but external to the region were also selected as controls (assay information summarized in Additional file 1: Table S4). A total of 11 samples were run in triplicate comprised of the sample(s) of interest, a calibrator (control) sample with known CN for the region of interest and a no-template-control (NTC). Real-time PCR was conducted according to manufacturer’s protocols using 10 ng of DNA sample in a final reaction volume of 20 μL. The assay was run on the real-time PCR machine (Applied Biosystems 7500; SDS software Version v1.4) according manufacturer’s protocols. The results were exported to CopyCaller v2.0 software (Applied Biosystems) for analysis.

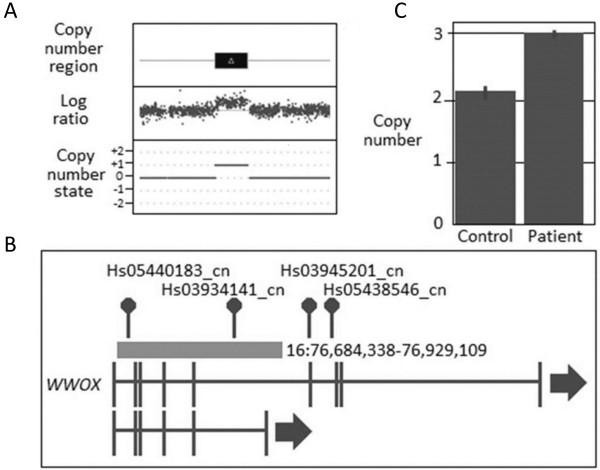

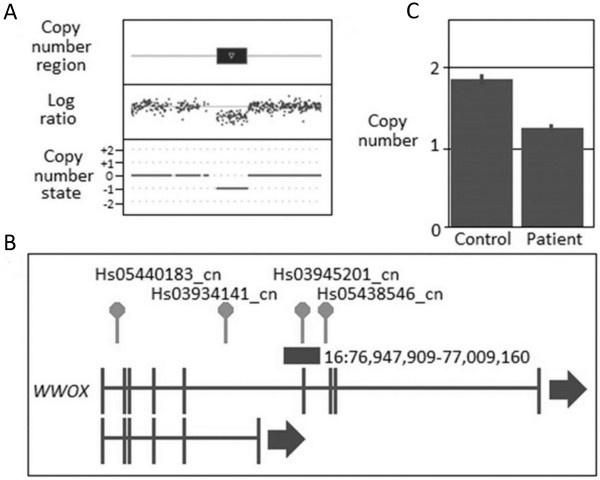

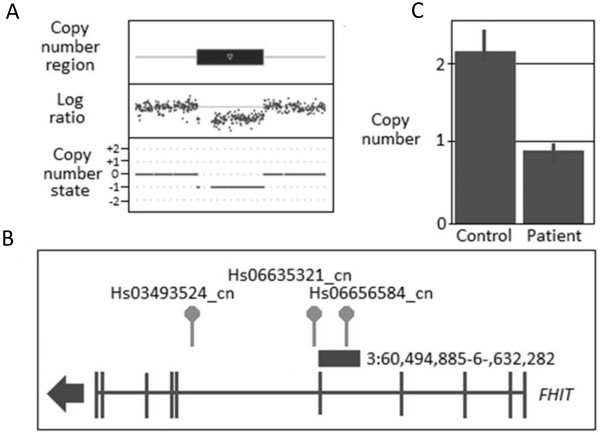

Three CNVs were validated using this secondary independent assay (Additional file 1: Table S5). The CNVs included a CN gain and a CN loss in the WWOX gene as well as a CN loss in the FHIT gene. Given the high concordance between the CNV calling within the experimental parameters set for this study and the independent copy number assays we considered that it was not necessary to confirm all CNVs using a second independent assay.

Results

Array resolution and CNV detection

Analysis of Cyto2.7 M array data revealed a total of 414 CNVs in 169 individuals assessed in this study (Table 1). CNVs detected ranged in size from 9.65 Kb to 1335.06 Kb. There was no difference in the average number of CNVs identified in the patients versus the controls (p = 0.75). The average genomic burden of CNVs also did not differ between patients (226.93 Kb) and controls (295.52 Kb), p = 0.30; or the average CNV size between patients (76.22 Kb) and controls (106.57 Kb), s, p = 0.07.

Table 1.

Summary of CNV results from the BC patients and control participants

| |

|

CNV Count |

CNV Size (Kb) |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total CNVs per group | Median CNVs per sample | Mean CNVs per sample | Total CNV affected genome per group | Mean total CNV affected genome per sample | Mean size of a CNV | ||

|

Patients |

129 |

310 |

2 |

2.40 |

29273.63 |

226.93 |

76.22 |

|

Controls |

40 |

104 |

2 |

2.60 |

11820.75 |

295.52 |

106.57 |

| p | - | - | - | 0.75 | - | 0.30 | 0.07 |

Occurrence and distribution of CNVs in fBC patients

Overall 310 CNVs were identified in fBC patients of which 35 also occurred in controls (Additional file 1: Table S6). Since these regions were represented in the control population they were removed from further analysis. Of the 275 CNVs unique to the patients (Additional file 1: Table S7), 94 have was previously described in the DGV and 39 spanned genomic regions that were common to multiple patients (Table 2). Of these 11 CNVs (located on chromosomes 2, 3, 4, 6, 11, 14, 15, 17 and 18) were common to two patients; three were common to three patients (located on chromosomes 4, 5 and 19); and two were common to four patients (located on chromosomes 3 and 18). Among these, three genomic regions (located chromosomes 6, 11 and 19) were considered novel (not reported in the DGV) and likely to represent regions of potential association with BC risk.

Table 2.

Genomic regions associated with unique CNVs identified in multiple patients

| Type | Chr | Start (bp)* | End (bp)* | Size (Kb) | Probes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

2 CNV gains | |||||

|

Gain |

2 |

13,119,088 |

13,199,687 |

80.6 |

48 |

|

Gain |

2 |

13,135,013 |

13,199,687 |

64.7 |

43 |

|

Gain |

2 |

82,055,473 |

82,163,764 |

108.3 |

85 |

|

Gain |

2 |

82,056,404 |

82,168,370 |

112.0 |

89 |

|

Gain |

3 |

958,296 |

1,012,953 |

54.7 |

33 |

|

Gain |

3 |

975,908 |

1,032,700 |

56.8 |

29 |

|

Gain |

6 |

27,738,385 |

27,764,062 |

25.7 |

26 |

|

Gain |

6 |

27,742,403 |

27,770,374 |

28.0 |

24 |

|

Gain |

15 |

79,783,294 |

79,876,946 |

93.7 |

77 |

|

Gain |

15 |

79,795,446 |

79,876,343 |

80.9 |

70 |

|

Gain |

17 |

21,503,478 |

21,648,413 |

144.9 |

25 |

|

Gain |

17 |

21,503,478 |

21,650,626 |

147.2 |

26 |

|

3 CNV gains | |||||

|

Gain |

4 |

25,672,202 |

25,703,024 |

30.8 |

31 |

|

Gain |

4 |

25,678,621 |

25,710,178 |

31.6 |

32 |

|

Gain |

4 |

25,680,434 |

25,710,412 |

30.0 |

31 |

|

Gain |

5 |

59,749,693 |

59,807,906 |

58.2 |

51 |

|

Gain |

5 |

59,749,693 |

59,807,906 |

58.2 |

51 |

|

Gain |

5 |

59,749,693 |

59,810,944 |

61.3 |

52 |

|

Gain |

19 |

36,911,234 |

36,939,557 |

28.3 |

36 |

|

Gain |

19 |

36,918,927 |

36,940,929 |

22.0 |

32 |

|

Gain |

19 |

36,918,927 |

36,944,555 |

25.6 |

36 |

|

2 CNV losses | |||||

|

Loss |

11 |

95,844,428 |

95,917,476 |

73.1 |

54 |

|

Loss |

11 |

95,844,428 |

95,917,476 |

73.1 |

54 |

|

Loss |

14 |

44,229,915 |

44,294,996 |

65.1 |

53 |

|

Loss |

14 |

44,229,915 |

44,294,996 |

65.1 |

53 |

|

Loss |

17 |

19,439,549 |

19,476,055 |

36.5 |

28 |

|

Loss |

17 |

19,439,549 |

19,476,055 |

36.5 |

28 |

|

Loss |

18 |

1,714,779 |

1,828,901 |

114.1 |

109 |

|

Loss |

18 |

1,714,779 |

1,828,901 |

114.1 |

109 |

|

4 CNV losses | |||||

|

Loss |

3 |

166,523,809 |

166,565,186 |

41.4 |

39 |

|

Loss |

3 |

166,523,809 |

166,565,186 |

41.4 |

39 |

|

Loss |

3 |

166,523,809 |

166,566,558 |

42.8 |

40 |

|

Loss |

3 |

166,525,250 |

166,565,186 |

39.9 |

38 |

|

Loss |

18 |

1,894,368 |

1,974,284 |

79.9 |

63 |

|

Loss |

18 |

1,894,368 |

1,974,284 |

79.9 |

63 |

|

Loss |

18 |

1,894,368 |

1,974,284 |

79.9 |

63 |

|

Loss |

18 |

1,894,368 |

1,974,284 |

79.9 |

63 |

|

2 CNV gain and loss | |||||

|

Gain |

4 |

160,917,340 |

161,068,954 |

151.6 |

119 |

| Loss | 4 | 160,983,513 | 161,011,918 | 28.4 | 29 |

Probes = number of markers within a CNV segment.

*set at first and last marker associated with the respective CNV.

Of the CNVs unique to patients 160 (58.18%) encompassed genes. A CNV located in SUPT3H was also excluded from analysis as it was identified to be affected by a re-arrangement in a control sample and considered unlikely to be associated with disease risk. Therefore a total of 159 genes were associated with a CNV were identified as being unique to the fBC patients and represent genes potentially associated with disease. A total of 24 genes associated with 44 CNVs (gains, losses or both) were identified in multiple individuals (as shown in Table 3): 19 genes, including LAMB3, NBN, IL8 and WWOX, were affected by a CNV in two individuals; PIK3R5 and POU2F3 were affected by a CNV in three individuals; ARHGEF12 and TMEM136 were affected by a CNV in four individuals; and NAMPT was affected by a CNV in five individuals.

Table 3.

Genes associated with unique CNVs identified across multiple patients

| Number of Patients | Gene | Loci | |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Gains |

2 |

B2M |

15q21.1 |

| |

2 |

DSCAM |

21q22.2 |

| |

2 |

G0S2 |

1q32.2 |

| |

2 |

GNG2 |

14q22.1 |

| |

2 |

GPR98 |

5q14.3 |

| |

2 |

IL8 |

4q13.3 |

| |

2 |

LAMB3 |

1q32.2 |

| |

2 |

LIMS1 |

2q13 |

| |

2 |

NBN |

8q21.3 |

| |

2 |

TAGAP |

6q25.3 |

| |

2 |

TRIM69 |

15q21.1 |

|

Both |

2 |

CNTN4 |

3p26.3 |

| |

2 |

IMMP2L |

7q31.1 |

| |

2 |

WWOX |

16q23.1 |

|

Losses |

2 |

ACYP2 |

2p16.2 |

| |

2 |

PCDH9 |

13q21.32 |

| |

2 |

SPINT4 |

20q13.12 |

| |

2 |

TSPYL6 |

2p16.2 |

| |

2 |

VAV3 |

1p13.3 |

| |

3 |

PIK3R5 |

17p13.1 |

| |

3 |

POU2F3 |

11q23.3 |

| |

4 |

ARHGEF12 |

11q23.3 |

| |

4 |

TMEM136 |

11q23.3 |

| 5 | NAMPT | 7q22.2 |

Rare CNVs in fBC patients

There were 95 rare CNVs identified in 42 of the fBC patients. Of these 70 were associated with 78 genes and were found in 27 patients. Out of the 78 genes SUPT3H was excluded from further analysis as it was identified in a healthy control subject. Ten genes that were disrupted due to the presence of a CNV had previously been associated with cancer [30,31] including ARHGAP26, ARHGEF12, CARD11, CPD, FAM135B, TSHR, MLLT11, PTK2B, RHOH and FHIT (Table 4). The remaining CNVs affecting 67 genes were unique and have not previously been associated with malignancy (listed in Additional file 1: Table S8). These genes potentially represent new candidates that require further investigation.

Table 4.

Results for the ten CNVs associated with seven patients which affect genes previously associated with cancer

| Genes | Dx | Type | Chr | Start (bp) | End (bp) | Size (Kb) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

FHIT

|

22 |

Loss |

3 |

60,494,885 |

60,632,282 |

137.4 |

|

CARD11

|

37 |

Gain |

7 |

2,946,394 |

2,996,375 |

50 |

|

FAM135B

|

38 |

Gain |

8 |

139,259,837 |

139,306,535 |

46.7 |

|

ARHGEF12

|

51 |

Gain |

11 |

119,697,081 |

119,723,342 |

26.3 |

|

TSHR

|

~49 |

Gain |

14 |

80,659,512 |

80,669,166 |

9.7 |

|

MLLT11

|

46 |

Gain |

1 |

149,289,549 |

149307059 |

17.5 |

|

CPD

|

Gain |

17 |

25,700,671 |

25,756,973 |

56.3 |

|

|

RHOH

|

28 | Gain |

4 |

39,864,888 |

39,888,181 |

23.3 |

|

ARHGAP26

|

Gain |

5 |

142,147,309 |

142,174,652 |

27.3 |

|

| PTK2B | Gain | 8 | 27,237,115 | 27,333,842 | 96.7 |

Gene, age of patient diagnosis (Dx), CNV type (gain or loss), location (chromosome, start and end) and CNV size are indicated.

Genomic changes involving BC susceptibility genes or the recently identified BC susceptibility loci

There are at least 61 genes including those involved in DNA DSBR and MMR that could potentially contribute to fBC [6,7,28,29]. CNV data for the 129 fBC patients and 40 controls was screened for genomic re-arrangements within or ±100 Kb either side of these 61 genes. Five patients were identified to harbour CN gains located within or in the vicinity of four genes (Table 5): one within RPA3 gene; two within the NBN gene; one 55.7 Kb upstream of the MRE11A gene and one other 89.2 Kb upstream of the CYP19A1 gene. All gains are predicted to result in disruption of the respective genes’ coding sequence (via the insertion of additional genomic material which is expected to result in loss of function). With respect to the NBN gene a CNV loss was also identified in a control residing in a region located 52.6 Kb downstream of the gene but did not appear to be associated with disruption of the coding sequence.

Table 5.

Search results for regions containing CN gains and CN losses within ±100 Kb the 61 genes associated with BC risk

| Genes | Type | Chr | Start (bp) | End (bp) | Size (Kb) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Patients |

RPA3 |

Gain |

7 |

7,670,435 |

7,697,631 |

27.2 |

| |

NBN |

Gain |

8 |

91,048,149 |

91,070,004 |

21.9 |

| |

NBN |

Gain |

8 |

91,050,795 |

91,088,236 |

37.4 |

| |

55.7 Kb upstream MRE11A |

Gain |

11 |

93,922,391 |

93,960,356 |

38.0 |

| |

89.2 Kb upstream CYP19A1 |

Gain |

15 |

49,507,272 |

49,579,058 |

71.8 |

| Control | 52.6 Kb downstream NBN | Loss | 8 | 90,913,791 | 90,962,106 | 48.3 |

CNV location (chromosome, start bp and end bp), size (Kb) and type; as well as the gene affected by the variant are indicated.

No CNVs were identified that were located in the same 41 genomic regions that have recently been reported as BC susceptibility loci [7].

The identification of a CNV that involved WWOX in two unrelated patients (see Table 6, Figures 1 and 2) was of interest as this gene is located in a fragile site (FRA16D) associated with cancer development and has been shown to interact with TP53 and ACK1[33] and has recently been reported to be involved in breast carcinogenesis [34,35]. Together, this suggests that loss of function of WWOX could potentially be involved in BC susceptibility. One patient harboured a CNV gain that was predicted to disrupt the coding sequence of the gene via the insertion of additional genomic material whereas the other patient had a CNV loss that is expected to result in loss of function. Both of these changes were confirmed using an independent CN assay (see Additional file 1: Table S5). A number of recent reports have also correlated BC development with changes in the FHIT gene which similarly to WWOX is located in a fragile site (FRA3B) and has again been linked to tumour development [36-43]. CNV analysis revealed a CN loss that encompassed FHIT (Table 6 and Figure 3) which was confirmed using an independent assay (Additional file 1: Table S5).

Table 6.

CNVs associated with fragile site FRA16D and FRA3B

| Chr | Start (bp) | End (bp) | Size (Kb) | Gene | Probes | DGV |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

16 |

76,684,338 |

76,929,109 |

244.8 |

WWOX |

222 |

Reported |

|

16 |

76,947,909 |

77,009,160 |

61.3 |

WWOX |

69 |

Reported |

| 3 | 60,494,885 | 60,632,282 | 137.4 | FHIT | 158 |

CNV location (chromosome, start bp and end bp) and size (Kb); as well as the confidence score associated with CNV call, the gene affected by the variant, the number of probes used to call the CNV and if the variant has previously been reported in the DGV.

Figure 1.

CNV results for WWOX duplication in fBC patient. (A) CNV profile from Cyto2.7 M array data defining the region of duplication including the genomic state (where 0 = the normal two copies and +1 = one extra copy; (B) Location of the duplication within the gene and with respect to the CN assays used in validating the variant; and (C) TaqMan CN Validation assay showing the duplication represented by Hs03934141_cn: note the normal two copies of this region identified in the control, confirmation of the aberrant three copies in the fBC patient and the CN range bars associated with the three technical replicates used to validate the CNVs.

Figure 2.

CNV results for WWOX deletion in fBC patient. (A) CNV profile from Cyto2.7 M array data defining the region of deletion including the genomic state (where 0 = the normal two copies and -1 = one less copy; (B) Location of the deletion within the gene and with respect to the CN assays used in validating the variant; and (C) TaqMan CN Validation assay showing the deletion represented by Hs03945201_cn: note the normal two copies of this region identified in the control, confirmation of the aberrant one copy in the fBC patient and the CN range bars associated with the three technical replicates used to validate the CNVs.

Figure 3.

CNV results for FHIT deletion in fBC patient. (A) CNV profile from Cyto2.7 M array data defining the region of deletion including the genomic state (where 0 = the normal two copies and -1 = one less copy; (B) Location of the deletion within the gene and with respect to the CN assays used in validating the variant; and (C) TaqMan CN Validation assay showing the deletion represented by Hs06656584_cn: note the normal two copies of this region identified in the control, confirmation of the aberrant one copy in the fBC patient and the CN range bars associated with the three technical replicates used to validate the CNVs.

Discussion

The association between CNVs and fBC is yet to be fully defined. In this study we provide evidence that CNVs are a potential explanation for small but significant number of fBC patients who do not harbour germline mutations in known susceptibility genes.

Genomic resolution provided by microarray technology has increased significantly allowing for the discovery of ever smaller CNVs. The resolution of the array used in this study was limited to the identification of CNVs greater than 9.65 Kb in size, and hence we cannot rule out the potential involvement of smaller CNVs in the aetiology of fBC. There have been a number of technical issues associated with the identification of CNVs that have compounded the difficulties in assessing the role of genomic rearrangements in disease. Different array platforms, software algorithms, batch effects and population stratification influence the accuracy of calls made to and comparisons of CNV data [44-46]. To help in reducing the influence of these effects a set of 40 older population controls was used as the basis to differentiate between CNVs associated with breast cancer and uninformative controls. All samples (both cases and controls) were processed on one platform and analysed using the same analysis software and experimental parameters. Comparison between the number and size of CNVs between patients and controls did not reveal any significant differences between cohorts. It is important to note the limited number of controls utilized in the current study represents a potential bias, however it is reassuring to note that despite this potential limitation, our observations are consistent with two previous reports on fBC (68 patients and 100 controls) and BRCA1-associated ovarian cancer (84 patients and 47 controls) [24,47].

We also identified 67 genes associated with novel CNVs that have yet to be linked with BC risk. It is interesting to note that many of these have been implicated in biological processes involving metabolism and biological regulation [48]. This provides the basis for further investigation into expanding the number of genes involved in BC development.

Our study has identified CNVs in close proximity to a number of genes previously associated with BC risk in a fBC cohort: ARHGEF12 has been proposed to be a candidate tumour suppressor gene in BC whereby its under expression (typically as a result of genomic loss) has been observed in BC cell lines and where re-induction of the gene resulted in reduced cell proliferation and colony formation [49]; Laminin 5 (LN5) genes (including LAMB3) have been shown to exhibit reduced expression as a result of epigenetic inactivation in 65% of BC cell lines [50]; NBN has been recently reported to be associated with BC risk [6]; and NAMPT has been shown to modify the effects of PARP inhibitors used in the treatment of triple-negative BCs suggesting the potential for a combination of NAMPT and PARP inhibitors in the treatment of this disease [51].

Of all the genes affected by a CNV identified in more than one patient, the most frequently reported for BC development has been aberrations in WWOX. This tumour suppressor gene has been shown to be critical for normal breast development [34] with mutations in exons 4 to 9 frequently observed in BC tumours [35]. High expression of WWOX has been shown to be beneficial in association with tamoxifen treatment [52]. We further evaluated two unrelated fBC patients, one harbouring a CNV gain and the other a CNV loss. In both cases, the genomic rearrangements are predicted to reduce WWOX expression and thereby contribute to disease risk. Our results suggest that inherited deficiencies in WWOX are associated with disease but we could not demonstrate that these alterations were transmitted across generations due to ethical considerations. Notwithstanding, the frequency at which we have observed variants occurring in this gene (>1.55%) suggests that they may account for a significant proportion of BRCA1/BRCA2 mutation negative fBC patients. Functional studies are required to determine the precise effect of these variants in the alteration of WWOX expression and BC development.

The identification of CNVs in close proximity to BC susceptibility genes and loci that either contributes to disease development directly or via more cryptic means expands our understanding of their contribution to disease risk in fBC. Our study identified CNVs residing in three genes RPA3, NBN, MRE11A and CYP19A1 which supports their involvement in BC [6,28,29,53-56]. Given the predicted disruption of RPA3, NBN, MRE11A and CYP19A1 it is likely that these variants are associated with disease.

Within our fBC cases we identified several genes within or in close proximity to rare CNVs which have previously been associated with BC: the putative oncogene MLLT11 (aka AF1Q) has been reported to be over expressed in a BC cell line affecting invasive and metastatic potential [57,58]; while PTK2B has been shown to be the most frequently lost kinase in sporadic BC tumours and is suggested to contribute to the disease phenotype [59]. Of the rare CNVs associated with malignancy, the gene most frequently associated with BC development is the tumour suppressor FHIT. FHIT has been reported multiple times to be genetically and epigenetically modified in breast tumours [36-41]; its expression has been reported to be protective against HER2-driven breast tumour development [42]; whereas reduced expression is associated with poor prognosis [43]. A germline intronic deletion in FHIT has also been identified in a pancreatic cancer study [60]. Given that we have found a constitutional CNV in FHIT we suggest that variants in this gene could also account for a fraction of fBC patients. As we were unable to obtain other family members it remains to be seen if these genomic re-arrangements confer significant disease risk in a family setting rather than being associated with disease progression.

A recent report using 68 patient and 100 controls suggested that rare CNVs may contribute to disease in a small proportion of fBC patients [24]. In contrast to our findings this study reported significantly lower percentages of rare CNVs in fBC patients (4%) compared to the level observed in the current study (30.65%) [24]. The discrepancies in these findings are most likely to be related to differences in sample populations, the type of array used (variation in array coverage and density), as well as the algorithm used by the analysis software [44-46]. These findings reinforce the need to obtain larger cohorts of patients and controls to better understand the contribution of CNVs to breast cancer development.

Conclusions

This study has revealed that there are a number of CNVs which may contribute to the development of fBC. Several previously reported BC susceptibility genes that include RPA3, NBN, MRE11A and CYP19A1 were found to be influenced by the presence of a CNV. It was also revealed by this investigation that three unrelated fBC patients harboured CNVs in WWOX and FHIT. We propose that variants in these genes may account for disease in a significant proportion of fBC patients. Overall the results of this study provide further grounds for further investigation into the presence of CNVs in larger series of fBC patients who do not harbour changes in known breast cancer susceptibility genes.

Abbreviations

BC: Breast Cancer; bp: Base pair; CGC: Cancer Gene Census; ChAS: Chromosome Analysis Suite (Affymetrix); CN: Copy Number; CNV: Copy Number Variants; Cyto2.7 M: Cytogenetic Whole Genome 2.7 M array; DGV: Database of Genomic Variants; DSB: Double Strand Breat; DSBR: DSB Repair; fBC: Familial Breast Cancer; HCS: Hunter Community Study; Kb: Kilobase; mapd: Median of absolute pair-wise difference; Mb: Megabase; MLPA: Multiplex Ligation-dependant Probe Amplification; MMR: Mismatch Repair; NCG: Network of Cancer Genes; NTC: No template control; QC: Quality control; SNP: Single nucleotide polymorphism; WavinessSd: Waviness standard deviation.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interest.

Authors’ contributions

ALM conducted the experiments and wrote the first draft of the manuscript. BAT-P, T-JE and DMG provided expertise in data analysis and interpretation as well as revising the manuscript. GNH provided critical review of the manuscript and helped design the experiments. RJS conceived the study, designed the experimental approach and reviewed and approved the final version of the manuscript prior to submission.

Supplementary Material

Regions of CNV data excluded from CNV analysis due to poor density of probe coverage. Table S2. Regions searched for CN gains and CN losses in and in the vicinity of (±100 Kb) of the 61 genes associated with BC risk. Table S3. Regions searched for CN gains and CN losses in and in the vicinity of (±100 Kb) of the 41 loci recently reported to be associated with BC risk. Table S4. Summary of location and length information for TaqMan copy number assays (Applied Biosystems) used to validate CN duplications and deletions in the FHIT and WWOX genes. Table S5. TaqMan copy number assay results for validation of WWOX and FHIT CNVs in fBC patients. Table S6. List of 35 CNVs identified in patients that are in-common with CNVs identified in controls. Table S7. List of 275 CNVs identified in patients that are unique compared to the CNVs identified in controls. Table S8. List of 67 genes associated with CNVs uniquely identified in patients and not yet associated with malignancy.

Contributor Information

Amy L Masson, Email: Amy.Masson@uon.edu.au.

Bente A Talseth-Palmer, Email: Bente.Talseth-Palmer@newcastle.edu.au.

Tiffany-Jane Evans, Email: T.Evans@newcastle.edu.au.

Desma M Grice, Email: desmariegrice3@gmail.com.

Garry N Hannan, Email: Garry.Hannan@CSIRO.au.

Rodney J Scott, Email: Rodney.Scott@newcastle.edu.au.

Acknowledgements

This work has been supported by the following funding bodies and institutions: Australian Rotary Health/Rotary District 9650, the Commonwealth Scientific and Industrial Research Organization (CSIRO), the University of Newcastle and the Hunter Medical Research Institute. Samples were provided by the Hunter Area Pathology Service and the Hunter Community Study.

References

- Jemal A, Bray F, Center MM, Ferlay J, Ward E, Forman D. Global cancer statistics. CA Canc J Clin. 2011;61:69–90. doi: 10.3322/caac.20107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lalloo F, Evans DG. Familial breast cancer. Clin Genet. 2012;82:105–114. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-0004.2012.01859.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peto J, Mack TM. High constant incidence in twins and other relatives of women with breast cancer. Nat Genet. 2000;26:411–414. doi: 10.1038/82533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gracia-Aznarez FJ, Fernandez V, Pita G, Peterlongo P, Dominguez O, de la Hoya M, Duran M, Osorio A, Moreno L, Gonzalez-Neira A, Rosa-Rosa JM, Sinilnikova O, Mazoyer S, Hopper J, Lazaro C, Southey M, Odefrey F, Manoukian S, Catucci I, Caldes T, Lynch HT, Hilbers FS, van Asperen CJ, Vasen HF, Goldgar D, Radice P, Devilee P, Benitez J. Whole exome sequencing suggests much of non-BRCA1/BRCA2 familial breast cancer is due to moderate and low penetrance susceptibility alleles. PLoS One. 2013;8:e55681. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0055681. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wong MW, Nordfors C, Mossman D, Pecenpetelovska G, Avery-Kiejda KA, Talseth-Palmer B, Bowden NA, Scott RJ. BRIP1, PALB2, and RAD51C mutation analysis reveals their relative importance as genetic susceptibility factors for breast cancer. Breast Canc Res Treat. 2011;127:853–859. doi: 10.1007/s10549-011-1443-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang B, Beeghly-Fadiel A, Long J, Zheng W. Genetic variants associated with breast-cancer risk: comprehensive research synopsis, meta-analysis, and epidemiological evidence. Lancet Oncol. 2011;12:477–488. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(11)70076-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Michailidou K, Hall P, Gonzalez-Neira A, Ghoussaini M, Dennis J, Milne RL, Schmidt MK, Chang-Claude J, Bojesen SE, Bolla MK, Wang Q, Dicks E, Lee A, Turnbull C, Rahman N, Fletcher O, Peto J, Gibson L, Dos Santos Silva I, Nevanlinna H, Muranen TA, Aittomaki K, Blomqvist C, Czene K, Irwanto A, Liu J, Waisfisz Q, Meijers-Heijboer H, Adank M, De La Chapelle A, Peltomaki P. Breast, Ovarian Cancer Susceptibility, C. Large-scale genotyping identifies 41 new loci associated with breast cancer risk. Nat Genet. 2013;45:353–361. doi: 10.1038/ng.2563. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palles C, Cazier JB, Howarth KM, Domingo E, Jones AM, Broderick P, Kemp Z, Spain SL, Guarino Almeida E, Salguero I, Sherborne A, Chubb D, Carvajal-Carmona LG, Ma Y, Kaur K, Dobbins S, Barclay E, Gorman M, Martin L, Kovac MB, Humphray S, Consortium C, Consortium WGS, Lucassen A, Holmes CC, Bentley D, Donnelly P, Taylor J, Petridis C, Roylance R. et al. Germline mutations affecting the proofreading domains of POLE and POLD1 predispose to colorectal adenomas and carcinomas. Nat Genet. 2013;45:136–144. doi: 10.1038/ng.2503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lynch HT, de la Chapelle A. Genetic susceptibility to non-polyposis colorectal cancer. J Med Genet. 1999;36:801–818. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuiper RP, Vissers LE, Venkatachalam R, Bodmer D, Hoenselaar E, Goossens M, Haufe A, Kamping E, Niessen RC, Hogervorst FB, Gille JJ, Redeker B, Tops CM, van Gijn ME, van den Ouweland AM, Rahner N, Steinke V, Kahl P, Holinski-Feder E, Morak M, Kloor M, Stemmler S, Betz B, Hutter P, Bunyan DJ, Syngal S, Culver JO, Graham T, Chan TL, Nagtegaal ID. et al. Recurrence and variability of germline EPCAM deletions in Lynch syndrome. Hum Mutat. 2011;32:407–414. doi: 10.1002/humu.21446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ligtenberg MJ, Kuiper RP, Chan TL, Goossens M, Hebeda KM, Voorendt M, Lee TY, Bodmer D, Hoenselaar E, Hendriks-Cornelissen SJ, Tsui WY, Kong CK, Brunner HG, van Kessel AG, Yuen ST, van Krieken JH, Leung SY, Hoogerbrugge N. Heritable somatic methylation and inactivation of MSH2 in families with Lynch syndrome due to deletion of the 3′ exons of TACSTD1. Nat Genet. 2009;41:112–117. doi: 10.1038/ng.283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chan TL, Yuen ST, Ho JW, Chan AS, Kwan K, Chung LP, Lam PW, Tse CW, Leung SY. A novel germline 1.8-kb deletion of hMLH1 mimicking alternative splicing: a founder mutation in the Chinese population. Oncogene. 2001;20:2976–2981. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1204376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nystrom-Lahti M, Kristo P, Nicolaides NC, Chang SY, Aaltonen LA, Moisio AL, Jarvinen HJ, Mecklin JP, Kinzler KW, Vogelstein B, De La Chapelle A, Peltomaki P. Founding mutations and Alu-mediated recombination in hereditary colon cancer. Nat Med. 1995;1:1203–1206. doi: 10.1038/nm1195-1203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stella A, Surdo NC, Lastella P, Barana D, Oliani C, Tibiletti MG, Viel A, Natale C, Piepoli A, Marra G, Guanti G. Germline novel MSH2 deletions and a founder MSH2 deletion associated with anticipation effects in HNPCC. Clin Genet. 2007;71:130–139. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-0004.2007.00745.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Plaschke J, Ruschoff J, Schackert HK. Genomic rearrangements of hMSH6 contribute to the genetic predisposition in suspected hereditary non-polyposis colorectal cancer syndrome. J Med Genet. 2003;40:597–600. doi: 10.1136/jmg.40.8.597. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delnatte C, Sanlaville D, Mougenot JF, Vermeesch JR, Houdayer C, Blois MC, Genevieve D, Goulet O, Fryns JP, Jaubert F, Vekemans M, Lyonnet S, Romana S, Eng C, Stoppa-Lyonnet D. Contiguous gene deletion within chromosome arm 10q is associated with juvenile polyposis of infancy, reflecting cooperation between the BMPR1A and PTEN tumor-suppressor genes. Am J Hum Genet. 2006;78:1066–1074. doi: 10.1086/504301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Hattem WA, Brosens LA, de Leng WW, Morsink FH, Lens S, Carvalho R, Giardiello FM, Offerhaus GJ. Large genomic deletions of SMAD4, BMPR1A and PTEN in juvenile polyposis. Gut. 2008;57:623–627. doi: 10.1136/gut.2007.142927. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alonso-Espinaco V, Giraldez MD, Trujillo C, van der Klift H, Munoz J, Balaguer F, Ocana T, Madrigal I, Jones AM, Echeverry MM, Velez A, Tomlinson I, Mila M, Wijnen J, Carvajal-Carmona L, Castells A, Castellvi-Bel S. Novel MLH1 duplication identified in Colombian families with Lynch syndrome. Genet Med. 2011;13:155–160. doi: 10.1097/GIM.0b013e318202e10b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morak M, Koehler U, Schackert HK, Steinke V, Royer-Pokora B, Schulmann K, Kloor M, Hochter W, Weingart J, Keiling C, Massdorf T, Holinski-Feder E. Biallelic MLH1 SNP cDNA expression or constitutional promoter methylation can hide genomic rearrangements causing Lynch syndrome. J Med Genet. 2011;48:513–519. doi: 10.1136/jmedgenet-2011-100050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clendenning M, Buchanan DD, Walsh MD, Nagler B, Rosty C, Thompson B, Spurdle AB, Hopper JL, Jenkins MA, Young JP. Mutation deep within an intron of MSH2 causes Lynch syndrome. Fam Canc. 2011;10:297–301. doi: 10.1007/s10689-011-9427-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Charames GS, Ramyar L, Mitri A, Berk T, Cheng H, Jung J, Bocangel P, Chodirker B, Greenberg C, Spriggs E, Bapat B. A large novel deletion in the APC promoter region causes gene silencing and leads to classical familial adenomatous polyposis in a Manitoba Mennonite kindred. Hum Genet. 2008;124:535–541. doi: 10.1007/s00439-008-0579-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rohlin A, Engwall Y, Fritzell K, Goransson K, Bergsten A, Einbeigi Z, Nilbert M, Karlsson P, Bjork J, Nordling M. Inactivation of promoter 1B of APC causes partial gene silencing: evidence for a significant role of the promoter in regulation and causative of familial adenomatous polyposis. Oncogene. 2011;30:4977–4989. doi: 10.1038/onc.2011.201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giarola M, Stagi L, Presciuttini S, Mondini P, Radice MT, Sala P, Pierotti MA, Bertario L, Radice P. Screening for mutations of the APC gene in 66 Italian familial adenomatous polyposis patients: evidence for phenotypic differences in cases with and without identified mutation. Hum Mutat. 1999;13:116–123. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1098-1004(1999)13:2<116::AID-HUMU3>3.0.CO;2-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krepischi AC, Achatz MI, Santos EM, Costa SS, Lisboa BC, Brentani H, Santos TM, Goncalves A, Nobrega AF, Pearson PL, Vianna-Morgante AM, Carraro DM, Brentani RR, Rosenberg C. Germline DNA copy number variation in familial and early-onset breast cancer. Breast Canc Res. 2012;14:R24. doi: 10.1186/bcr3109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suehiro Y, Okada T, Shikamoto N, Zhan Y, Sakai K, Okayama N, Nishioka M, Furuya T, Oga A, Kawauchi S, Maeda N, Tamesa M, Nagashima Y, Yamamoto S, Oka M, Hinoda Y, Sasaki K. Germline copy number variations associated with breast cancer susceptibility in a Japanese population. Tumour Biol. 2013;34:947–952. doi: 10.1007/s13277-012-0630-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McEvoy M, Smith W, D’Este C, Duke J, Peel R, Schofield P, Scott R, Byles J, Henry D, Ewald B, Hancock S, Smith D, Attia J. Cohort profile: The Hunter Community Study. Int J Epidemiol. 2010;39:1452–1463. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyp343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller SA, Dykes DD, Polesky HF. A simple salting out procedure for extracting DNA from human nucleated cells. Nucleic Acids Res. 1988;16:1215. doi: 10.1093/nar/16.3.1215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murata H, Khattar NH, Gu L, Li GM. Roles of mismatch repair proteins hMSH2 and hMLH1 in the development of sporadic breast cancer. Canc Lett. 2005;223:143–150. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2004.09.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vodusek AL, Novakovic S, Stegel V, Jereb B. Genotyping of BRCA1, BRCA2, p53, CDKN2A, MLH1 and MSH2 genes in a male patient with secondary breast cancer. Radiol Oncol. 2011;45:296–299. doi: 10.2478/v10019-011-0031-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cancer Gene Census. Cancer Genome Project Wellcome Trust Sanger Institute. 2012.

- D’Antonio M, Pendino V, Sinha S, Ciccarelli FD. Network of Cancer Genes (NCG 3.0): integration and analysis of genetic and network properties of cancer genes. Nucleic Acids Res. 2012;40:D978–D983. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkr952. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- QuickCalcs - T test. GraphPad Software Inc., GraphPad Software Inc. 2013.

- Chang NS, Pratt N, Heath J, Schultz L, Sleve D, Carey GB, Zevotek N. Hyaluronidase induction of a WW domain-containing oxidoreductase that enhances tumor necrosis factor cytotoxicity. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:3361–3370. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M007140200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abdeen SK, Salah Z, Maly B, Smith Y, Tufail R, Abu-Odeh M, Zanesi N, Croce CM, Nawaz Z, Aqeilan RI. Wwox inactivation enhances mammary tumorigenesis. Oncogene. 2011;30:3900–3906. doi: 10.1038/onc.2011.115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ekizoglu S, Muslumanoglu M, Dalay N, Buyru N. Genetic alterations of the WWOX gene in breast cancer. Med Oncol. 2012;29:1529–1535. doi: 10.1007/s12032-011-0080-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campiglio M, Pekarsky Y, Menard S, Tagliabue E, Pilotti S, Croce CM. FHIT loss of function in human primary breast cancer correlates with advanced stage of the disease. Canc Res. 1999;59:3866–3869. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cecener G, Egeli U, Tunca B, Tasdelen I, Tolunay S, Bilgel N. Importance of novel sequence alterations in the FHIT gene on formation of breast cancer. Tumori. 2007;93:597–603. doi: 10.1177/030089160709300614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iliopoulos D, Guler G, Han SY, Druck T, Ottey M, McCorkell KA, Huebner K. Roles of FHIT and WWOX fragile genes in cancer. Canc Lett. 2006;232:27–36. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2005.06.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ismail HM, Medhat AM, Karim AM, Zakhary NI. Multiple patterns of FHIT gene homozygous deletion in Egyptian breast cancer patients. Int J Breast Canc. 2011;2011:325947. doi: 10.4061/2011/325947. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ismail HM, Medhat AM, Karim AM, Zakhary NI. FHIT gene and flanking region on chromosome 3p are subjected to extensive allelic loss in Egyptian breast cancer patients. Mol Carcinog. 2011;50:625–634. doi: 10.1002/mc.20797. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Negrini M, Monaco C, Vorechovsky I, Ohta M, Druck T, Baffa R, Huebner K, Croce CM. The FHIT gene at 3p14.2 is abnormal in breast carcinomas. Canc Res. 1996;56:3173–3179. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bianchi F, Tagliabue E, Menard S, Campiglio M. Fhit expression protects against HER2-driven breast tumor development: unraveling the molecular interconnections. Cell Cycle. 2007;6:643–646. doi: 10.4161/cc.6.6.4033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arun B, Kilic G, Yen C, Foster B, Yardley DA, Gaynor R, Ashfaq R. Loss of FHIT expression in breast cancer is correlated with poor prognostic markers. Canc Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2005;14:1681–1685. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-04-0278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dellinger AE, Saw SM, Goh LK, Seielstad M, Young TL, Li YJ. Comparative analyses of seven algorithms for copy number variant identification from single nucleotide polymorphism arrays. Nucleic Acids Res. 2010;38:e105. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkq040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsuang DW, Millard SP, Ely B, Chi P, Wang K, Raskind WH, Kim S, Brkanac Z, Yu CE. The effect of algorithms on copy number variant detection. PLoS One. 2010;5:e14456. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0014456. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang D, Qian Y, Akula N, Alliey-Rodriguez N, Tang J, Bipolar Genome S, Gershon ES, Liu C. Accuracy of CNV Detection from GWAS Data. PLoS One. 2011;6:e14511. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0014511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoshihara K, Tajima A, Adachi S, Quan J, Sekine M, Kase H, Yahata T, Inoue I, Tanaka K. Germline copy number variations in BRCA1-associated ovarian cancer patients. Genes Chromosomes Canc. 2011;50:167–177. doi: 10.1002/gcc.20841. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang B, Kirov S, Snoddy J. WebGestalt: an integrated system for exploring gene sets in various biological contexts. Nucleic Acids Res. 2005;33:W741–W748. doi: 10.1093/nar/gki475. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ong DC, Ho YM, Rudduck C, Chin K, Kuo WL, Lie DK, Chua CL, Tan PH, Eu KW, Seow-Choen F, Wong CY, Hong GS, Gray JW, Lee AS. LARG at chromosome 11q23 has functional characteristics of a tumor suppressor in human breast and colorectal cancer. Oncogene. 2009;28:4189–4200. doi: 10.1038/onc.2009.266. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sathyanarayana UG, Padar A, Huang CX, Suzuki M, Shigematsu H, Bekele BN, Gazdar AF. Aberrant promoter methylation and silencing of laminin-5-encoding genes in breast carcinoma. Clin Canc Res. 2003;9:6389–6394. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bajrami I, Kigozi A, Van Weverwijk A, Brough R, Frankum J, Lord CJ, Ashworth A. Synthetic lethality of PARP and NAMPT inhibition in triple-negative breast cancer cells. EMBO Mol Med. 2012;4:1087–1096. doi: 10.1002/emmm.201201250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gothlin Eremo A, Wegman P, Stal O, Nordenskjold B, Fornander T, Wingren S. Wwox expression may predict benefit from adjuvant tamoxifen in randomized breast cancer patients. Oncol Rep. 2013;29:1467–1474. doi: 10.3892/or.2013.2261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bartkova J, Tommiska J, Oplustilova L, Aaltonen K, Tamminen A, Heikkinen T, Mistrik M, Aittomaki K, Blomqvist C, Heikkila P, Lukas J, Nevanlinna H, Bartek J. Aberrations of the MRE11-RAD50-NBS1 DNA damage sensor complex in human breast cancer: MRE11 as a candidate familial cancer-predisposing gene. Mol Oncol. 2008;2:296–316. doi: 10.1016/j.molonc.2008.09.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heikkinen K, Karppinen SM, Soini Y, Makinen M, Winqvist R. Mutation screening of Mre11 complex genes: indication of RAD50 involvement in breast and ovarian cancer susceptibility. J Med Genet. 2003;40:e131. doi: 10.1136/jmg.40.12.e131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hsu HM, Wang HC, Chen ST, Hsu GC, Shen CY, Yu JC. Breast cancer risk is associated with the genes encoding the DNA double-strand break repair Mre11/Rad50/Nbs1 complex. Canc Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2007;16:2024–2032. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-07-0116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yuan SS, Hou MF, Hsieh YC, Huang CY, Lee YC, Chen YJ, Lo S. Role of MRE11 in cell proliferation, tumor invasion, and DNA repair in breast cancer. J Natl Canc Inst. 2012;104:1485–1502. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djs355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang XZ, Li DQ, Hou YF, Wu J, Lu JS, Di GH, Jin W, Ou ZL, Shen ZZ, Shao ZM. Identification of the functional role of AF1Q in the progression of breast cancer. Breast Canc Res Treat. 2008;111:65–78. doi: 10.1007/s10549-007-9761-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li DQ, Hou YF, Wu J, Chen Y, Lu JS, Di GH, Ou ZL, Shen ZZ, Ding J, Shao ZM. Gene expression profile analysis of an isogenic tumour metastasis model reveals a functional role for oncogene AF1Q in breast cancer metastasis. Eur J Canc. 2006;42:3274–3286. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2006.07.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Naylor TL, Greshock J, Wang Y, Colligon T, Yu QC, Clemmer V, Zaks TZ, Weber BL. High resolution genomic analysis of sporadic breast cancer using array-based comparative genomic hybridization. Breast Canc Res. 2005;7:R1186–R1198. doi: 10.1186/bcr1356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lucito R, Suresh S, Walter K, Pandey A, Lakshmi B, Krasnitz A, Sebat J, Wigler M, Klein AP, Brune K, Palmisano E, Maitra A, Goggins M, Hruban RH. Copy-number variants in patients with a strong family history of pancreatic cancer. Canc Biol Ther. 2007;6:1592–1599. doi: 10.4161/cbt.6.10.4725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Regions of CNV data excluded from CNV analysis due to poor density of probe coverage. Table S2. Regions searched for CN gains and CN losses in and in the vicinity of (±100 Kb) of the 61 genes associated with BC risk. Table S3. Regions searched for CN gains and CN losses in and in the vicinity of (±100 Kb) of the 41 loci recently reported to be associated with BC risk. Table S4. Summary of location and length information for TaqMan copy number assays (Applied Biosystems) used to validate CN duplications and deletions in the FHIT and WWOX genes. Table S5. TaqMan copy number assay results for validation of WWOX and FHIT CNVs in fBC patients. Table S6. List of 35 CNVs identified in patients that are in-common with CNVs identified in controls. Table S7. List of 275 CNVs identified in patients that are unique compared to the CNVs identified in controls. Table S8. List of 67 genes associated with CNVs uniquely identified in patients and not yet associated with malignancy.