Abstract

In an ongoing effort to develop a renal tracer with pharmacokinetic properties comparable to PAH and superior to those of both 99mTc-MAG3 and 131I-OIH, we evaluated a new renal tricarbonyl radiotracer based on the aspartic-N-monoacetic acid ligand, 99mTc(CO)3(ASMA). The ASMA ligand features two carboxyl groups and an amine function for the coordination of the {99mTc(CO)3}+ core as well as a dangling carboxylate to facilitate rapid renal clearance.

Methods

rac-ASMA and L-ASMA were labeled with a 99mTc-tricarbonyl precursor and radiochemical purity of the labeled products was determined by HPLC. Using 131I-OIH as an internal control, we evaluated biodistribution in normal rats with 99mTc(CO)3(ASMA) isomers and in rats with renal pedicle ligation with 99mTc(CO)3(rac-ASMA). Clearance studies were conducted in 4 additional rats. In vitro radiotracer stability was determined in PBS buffer pH 7.4 and in challenge studies with cysteine and histidine. 99mTc(CO)3(ASMA) metabolites in urine were analyzed by HPLC.

Results

Both 99mTc(CO)3(ASMA) preparations had > 99% radiochemical purity and were stable in PBS buffer pH 7.4 for 24 h. Challenge studies on both revealed no significant displacement of the ligand. In normal rats, % injected dose in urine at 10 and 60 min for both preparations averaged 103% and 106% that of 131I-OIH, respectively. The renal clearances of 99mTc(CO)3(rac-ASMA) and 131I-OIH were comparable (P = 0.48). The tracer was excreted unchanged in the urine, proving its in vivo stability. In pedicle-ligated rats, 99mTc(CO)3(rac-ASMA) had less excretion into the bowel (P < 0.05) and was better retained in the blood (P < 0.05) than 131I-OIH.

Conclusion

Both 99mTc(CO)3(ASMA) complexes have pharmacokinetic properties in rats comparable to or superior to those of 131I-OIH, and human studies are warranted for their further evaluation.

Keywords: Technetium-99m (99mTc), Tricarbonyl, Kidney, Renal radiopharmaceuticals, 131I-ortho-iodohippurate, 99mTc(CO)3(ASMA)

Chronic kidney disease (CKD) has emerged as a serious health problem worldwide. In the US alone, an estimated 13% of the adult population have CKD (1) and this number is increasing yearly due to the rising prevalence of diabetes, hypertension, obesity, cardiovascular disease superimposed on an aging population (2–5). Moreover, the incidence of CKD in children has also steadily increased during the past two decades (6). Early detection and diagnosis can lead to treatment that will reduce the risk of kidney failure.

The classification of CKD is currently based on the estimated GFR using a 4 variable algorithm which attempts to compensate for the fact that the serum creatinine may not become elevated until over 50% of the renal function has been lost (7). Radionuclide imaging may detect unsuspected renal disease in patients with a normal serum creatinine and continues to have an important role in evaluating suspected obstruction and renovascular hypertension and in monitoring renal function through measurements of glomerular filtration and effective renal plasma flow (ERPF). The gold standard for the determination of ERPF is p-aminohippurate (PAH). In practice, however, measurement of PAH clearance required a constant plasma infusion and time consuming analysis, limiting its use in a clinical setting. 131I-o-iodohippurate (131I-OIH) is a radioactive standard used as an imaging agent and as a tracer to measure ERPF, although its clearance is still only 85–90% that of PAH (8). 131I-OIH commercial production has been discontinued in many countries because of the suboptimal characteristics of 131I (Emax = 364 keV) and the fact that its beta emission can result in a high radiation dose, particularly to the kidneys and thyroid in patients with impaired renal function (9).

Simple and rapid labeling methods with the 99mTc isotope have been developed for clinical applications (10, 11) because of the 99mTc highly favorable physical characteristics (t1/2 = 6 h, Emax = 140 keV), easy availability and low cost. Although a number of 99mTc complexes have been tested as potential alternatives for 131I-OIH (12–21), 99mTc-mercaptoacetyltriglycine (99mTc-MAG3) was shown to have favorable properties, has become commercially available, and is the most widely used 99mTc renal tracer in the United States (22, 23). Nevertheless, 99mTc-MAG3 is not an ideal replacement for 131I-OIH because its clearance is only 50–60% that of 131I-OIH and it does not provide a direct measurement of effective renal plasma flow (ERPF). Our recent studies showed that a new 99mTc renal agent based on the nitrilotriacetic acid ligand (Fig. 1), 99mTc(CO)3(NTA), and 131I-OIH had essentially identical pharmacokinetics in rats (24) and subjects with normal renal function (21), suggesting that an anionic renal tracer with a {99mTc(CO)3}+ core and an aminopolycarboxylate chelate is capable of providing a measurement of ERPF in humans equivalent to that of 131I-OIH. However, the promising biological properties of 99mTc(CO)3(NTA) still need to be confirmed in patients with impaired renal function. Even if 99mTc(CO)3(NTA) proves to be equivalent to 131I-OIH in patients with renal failure, 99mTc(CO)3(NTA) clearance is still likely to be inferior to that of PAH because the clearance of 131I-OIH is only 84% that of PAH (25).

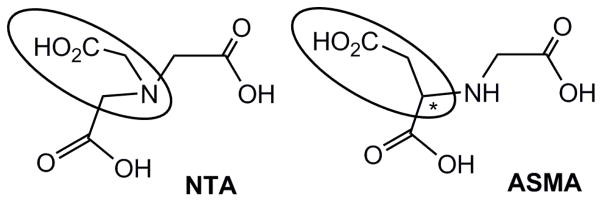

FIGURE 1.

Structure of nitrilotriacetic acid (NTA) and aspartic-N-monoacetic acid (ASMA) ligands. The ellipse encloses the dangling carboxyl group and the asterisk indicates an asymmetric carbon.

Our goal was to assess a new 99mTc(CO)3(NTA) isomer, 99mTc(CO)3(ASMA) (ASMA stands for aspartic-N-monoacetic acid, Fig. 1) in an animal model to determine if a change in ligand design could lead to a renal tracer with improved pharmacokinetic properties.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

General

The aspartic-N-monoacetic acid ligand was synthesized as previously described as a racemic mixture of D- and L-isomers (rac-ASMA) (26) and as the enantiomerically pure L-isomer (L-ASMA) (27). 99mTc-pertechnetate (Na99mTcO4−) was eluted from a 99Mo/99mTc generator (Lantheus Medical Imaging, Billerica, MA) with 0.9% saline. IsoLink vials were obtained as a gift from Covidien (St. Louis Missouri) and [99mTc(CO)3(H2O)3]+ was prepared according to the manufacturer’s insert. The HPLC chromatograms for the 99mTc tracers were obtained by use of a Beckman System Gold Nouveau apparatus equipped with a model 170 radiometric detector and a model 166 ultraviolet light-visible light detector, and a Beckman C18 RP Ultrasphere octyldecyl silane column (5-μm, 4.6 × 250 mm). The flow rate of the mobile phase was 1 mL/min, the mobile phase consisted of aqueous 0.05 M triethylammonium phosphate buffer pH 2.5 (solvent A) and methanol (solvent B), and the gradient method used was the same as reported previously (28). Tissue/organ radioactivity was measured using an automated 2480 Wizard 2 gamma counter (Perkin Elmer) with a 3-inch NaI(Tl) detector. All animal experiments followed the principles of laboratory animal care and were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of Emory University. Re(CO)3(ASMA) was used as a non-radioactive analog of 99mTc(CO)3(ASMA) and its synthesis and characterization will be published elsewhere. 99mTc(CO)3(ASMA) is used as a general reference to the complex, which may be a mixture of forms, whereas a specific form is designated as, e.g., 99mTc(CO)3(L-ASMA).

99mTc Radiolabeling

Both rac-ASMA and L-ASMA were labeled in a similar manner to form their 99mTc-complexes. The 99mTc-tricarbonyl precursor, [99mTc(CO)3(H2O)3]+, was prepared fresh daily by adding 1.0 mL of a Na99mTcO4 saline solution to an IsoLink kit and heating at 100 °C for 20 min. After neutralization with 0.12 mL of 1 M HCl, 0.5 mL of the [99mTc(CO)3(H2O)3]+ precursor was added to a sealed vial containing ~0.2 mg of ASMA in 0.2 mL of water. The pH of the solution was adjusted to ~ 7 with 1 M NaOH and the mixture was heated at 70 °C for 30 min, cooled to room temperature. 99mTc(CO)3(ASMA) was then purified by HPLC as described above. The two diastereomers of 99mTc(CO)3(ASMA) formed during the labeling process could not be separated by HPLC, and the tracer was collected in a single fraction and was further evaluated as a mixture of products. The aqueous solution of 99mTc(CO)3(ASMA) collected was diluted in a physiological phosphate buffer pH 7.4 to obtain a concentration of 3.7 MBq/mL for in vivo experiments. The sample of the isolated 99mTc complex was mixed with the aqueous solution of its Re analog, Re(CO)3(ASMA), and the mixture was analyzed by HPLC to confirm the 99mTc tracer’s identity.

In vitro Stability

Solution of 99mTc(CO)3(ASMA) was buffered in a physiological phosphate buffer at pH 7.4 and evaluated by HPLC for up to 24 h to assess complex integrity. In addition, the isolated 99mTc(CO)3(ASMA) complex (0.1 mL in the bufferd solution) was incubated with 0.1 M solutions of histidine and cysteine (0.9 mL), respectively, at 37 °C, and aliquots of the incubation mixture were analyzed by HPLC at 2 and 4 h to determine the degree of decomposition.

Biodistribution Studies

99mTc(CO)3 (ASMA) was evaluated in two experimental groups of rats (Sprague–Dawley, 203–350 g each, Charles River, MA). Rats in both groups were anesthetized with ketamine–xylazine (2 mg/kg of body weight) injected intramuscularly, with additional supplemental anesthetic as needed. In the first group of eight normal rats (Group A), the bladder was catheterized by use of heat-flared PE-50 tubing (Becton, Dickinson and Co.) for urine collection. The second group of four rats (Group B) was prepared to produce a model of renal failure. In that group, the abdomen was opened by a midline incision and both renal pedicles were identified and ligated just before radiotracer administration; thus, no urine was collected.

Each rat was injected intravenously via a tail vein with a 0.2 mL of a solution containing 99mTc(CO)3(ASMA) (3.7 MBq/mL [100 μCi/mL]) and 131I-OIH (925 kBq/mL [25 μCi/mL]) in PBS buffer pH 7.4. One additional aliquot of the 99mTc and 131I tracer solution (0.2 mL) for each time point was diluted to 100 mL, and three 1-mL portions of the resulting solution were used as standards.

In Group A, four animals were sacrificed at 10 min, and four animals were sacrificed at 60 min after injection. A blood sample was obtained, and the kidneys, heart, lungs, spleen, stomach and intestines were removed and placed in counting vials. The whole liver was weighed, and random sections were obtained for counting. Samples of blood and urine were also placed in counting vials and weighed. Each sample and the standards were counted for radioactivity by using an automated gamma-counter; counts were corrected for background radiation, physical decay, and spillover of 131I counts into the 99mTc window. The percentage of the dose in each tissue or organ was calculated by dividing the counts in each tissue or organ by the total injected counts. The percentage injected dose in whole blood was estimated by assuming a blood volume of 6.5% of total body weight. Three rats probably became hypotensive during the study since two rats in 10 min Group A study of 99mTc(CO)3(L-ASMA) and one rat in the 60 min Group A study of 99mTc(CO)3(rac-ASMA) produced very little urine; although these three rats could be considered as a model of reduced function, they were eliminated from the combined data analysis even though the ratio of 99mTc/131I in the urine ranged from 99–103%. The Group B rats were sacrificed 60 min after injection. Selected organs and blood were collected and counted as described above.

Renal Clearance

Four male rats were anesthetized as described above and placed on a heated surgical table. Following tracheostomy, the left jugular vein was cannulated with two pieces of PE-50 tubing (one for infusion of radiopharmaceuticals and one to infuse normal saline (5.8 mL/h) to maintain hydration and additional anesthetic (5 mg/h) as necessary). The right carotid artery was cannulated for blood sampling and the bladder was catheterized by use of PE-50 tubing. The core temperature of each animal was continually monitored throughout the study using a rectal temperature probe. 99mTc(CO)3(rac-ASMA) (3.7 MBq/mL [100 μCi/mL]) and 131I-OIH (1.85 MBq/mL [50 μCi/mL]), were co-infused at a flow rate of 1.7 mL/h for 60 min to establish steady-state blood levels. Urine was then collected for three 10-min clearance periods and midpoint blood samples (0.5 mL) were obtained. The blood samples were centrifuged for 15 min and plasma samples were obtained. Renal clearance (Cl) was determined by utilizing the equation: , where U is the urine radioactivity concentration, V is the urine volume excreted per minute and P is the plasma radioactivity concentration. The average of the three 10-min clearance measurements was used as the clearance value.

Metabolism Studies

Each 99mTc(CO)3(ASMA) preparation was administrated via the tail vain as a bolus injection (18.5 MBq [0.5 mCi]) in two additional rats. Urine was collected for 15 min and analyzed by HPLC to determine whether the tracer was metabolized or excreted unchanged in the urine.

Statistical Analysis

All results are expressed as the mean ± SD. To determine the statistical significance between the measured variables of the two groups, comparisons were made using the 2-tailed Student t test for paired data. P < 0.05 was considered to be statistically significant.

RESULTS

99mTc Radiolabeling

The radiolabeling of both L-ASMA and rac-ASMA ligands with the [99mTc(CO)3(H2O)3]+ precursor was performed under mild, aqueous pH 7 conditions and provided the appropriate 99mTc(CO)3(ASMA) tracer with high radiochemical purity (> 99%) in both preparations, after HPLC isolation. During the purification process, the 99mTc tracer was separated from the excess of unlabeled ligand. Note that since all in vivo studies presented here were done at physiological pH, we have omitted the radiotracer’s charge in our discussion and will simply refer to it as 99mTc(CO)3(ASMA). However, our evidence indicates that at physiological pH the tracer is dianionic, [99mTc(CO)3(ASMA)]2−, with trianionic ASMA bound via two five-membered chelate rings.

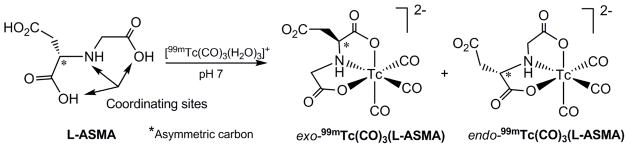

The coordination of the L-ASMA ligand possessing an asymmetric carbon to the symmetrical 99mTc-tricarbonyl core generates an asymmetric 99mTc center and as a consequence the formation of two diastereomers of 99mTc(CO)3(ASMA) (Fig. 2). The dangling carboxyl group projects away from the carbonyl ligands (exo) in one diastereomer and toward the carbonyl ligands (endo) in the other diastereomer (Fig. 2). The presence of diastereomers was evident on the radiochromatograms of the HPLC purified 99mTc(CO)3(L-ASMA). Representative chromatograms of the reaction mixture (Fig. 3A) and of the purified radiolabeled compound (Fig. 3B) are shown in Fig. 3. In chromatograms of the reaction mixture (Fig. 3A), the radioactive peak eluting at about 9 min coincides with the peak of residual 99mTc-pertechnetate, typically present at ~1–2%. Almost identical retention times of diastereomers prevented their separation; thus, the 99mTc(CO)3(L-ASMA) tracer was collected in a single fraction and was further evaluated as a mixture of two diastereomers. The {99mTc(CO)3}+ labeling of rac-ASMA (a mixture of L and D isomers) produced four stereoisomeric forms: two enantiomeric pairs of diastereomers. A less likely formulation would interchange the roles of the aspartic acid carboxyl groups. However, this would produce one less favorable six-membered chelate ring.

FIGURE 2.

Preparation of two diastereomers of 99mTc(CO)3(L-ASMA).

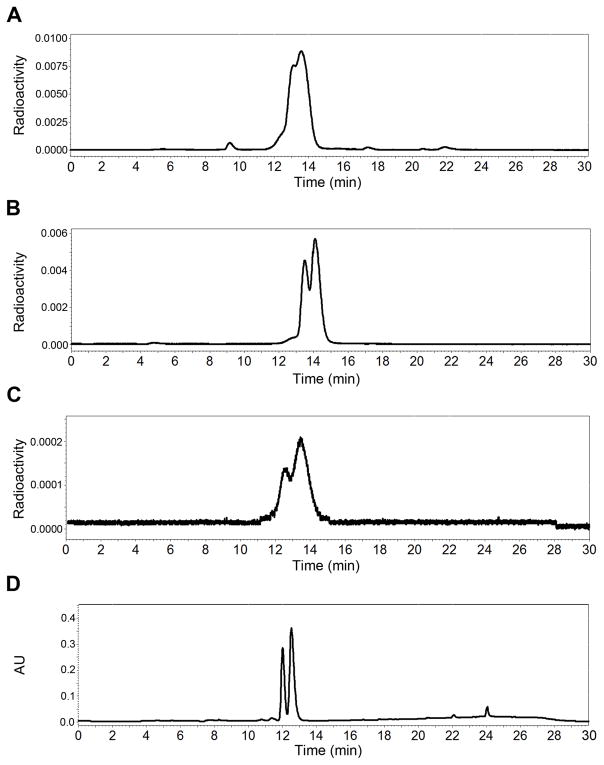

FIGURE 3.

HPLC of 99mTc(CO)3(L-ASMA): labeling mixture (A), before injection (B), in urine at 15 min after injection (C), and UV-trace (254 nm) of Re(CO)3(L-ASMA) (D).

The virtually identical coordination parameters and physical properties of 99mTc and Re complexes facilitate understanding the chemistry and structure of the radioactive 99mTc agents. To confirm the diastereomeric formulation of the 99mTc(CO)3(ASMA) tracers (Fig. 2), Re analogs have been prepared and their synthesis and full characterization will be published elsewhere. As for the 99mTc radiotracer, Re(CO)3(ASMA) is also formed exclusively as a mixture of two diastereomers with structures shown in Fig. 2 for the 99mTc(CO)3(ASMA) isomers. Both 99mTc and Re complexes showed nearly identical retention time under HPLC conditions given above when they were co-injected (Fig. 3B and 3D, respectively), confirming the chemical identity of the 99mTc(CO)3(ASMA) tracers.

To assess the tracer’s stability, 99mTc(CO)3(ASMA) was incubated at physiological pH for 24 h and no measurable decomposition was observed when an aliquot of the incubated sample was analyzed by HPLC. In addition, the 99mTc(CO)3(ASMA) tracer was analyzed by HPLC for stability against an excess of cysteine or histidine. In both cases, no additional peaks were observed in HPLC studies proving that no transchelation by cysteine and histidine occurred and that 99mTc(CO)3(ASMA) was completely robust over 4 h under these conditions.

In vivo Biodistribution and Metabolism of 99mTc(CO)3(ASMA)

In vivo biodistribution results of 99mTc(CO)3(L-ASMA) and 99mTc(CO)3(rac-ASMA) expressed as a percent of injected dose (%ID) for selected tissue/organs are summarized in Table 1 and Fig. 4. We compared the biological behavior of 99mTc(CO)3(ASMA) to that of 131I-OIH, the clinical standard for the measurement of ERPF, in normal rats and in a model of complete renal failure (rats with renal pedicle ligation).

TABLE 1.

Biodistribution (% ID) of 99mTc(CO)3(ASMA) and 131I-OIH in Normal (Group A) and Renal Pedicle Ligated (Group B) Rats.

| Blood | Liver | Stomach | Intestines | Kidney | Urine | % Urine 99mTc/131I | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 10 min Group A | |||||||

| 99mTc-rac-ASMA* | 5.2 ± 1.7 | 2.5 ± 0.3 | 0.2 ± 0.0 | 0.5 ± 0.1 | 6.7 ± 1.0 | 51.3 ± 6.2 | 106 ± 6 |

| 131I -OIH | 6.7 ± 1.9 | 3.7 ± 0.6 | 0.3 ± 0.1 | 1.7 ± 0.3 | 6.5 ± 0.7 | 48.3 ± 4.9 | |

| P | 0.0711 | 0.0178 | 0.0041 | 0.1104 | |||

| 99mTc-L-ASMA† | 4.7 ± 0.9 | 3.7 ± 1.2 | 0.2 ± 0.0 | 0.8 ± 0.2 | 4.3 ± 2.2 | 51.1 ± 7.3 | 100 ± 3 |

| 131I -OIH | 5.1 ± 1.0 | 2.9 ± 0.3 | 0.3 ± 0.1 | 1.5 ± 0.3 | 4.0 ± 1.8 | 50.9 ± 6.0 | |

| P | 0.0704 | 0.4576 | 0.0792 | 0.9003 | |||

| 60 min Group A | |||||||

| 99mTc-rac-ASMA‡ | 0.2 ± 0.0 | 0.2 ± 0.1 | 0.0 ± 0.0 | 0.4 ± 0.1 | 0.2 ± 0.1 | 94.4 ± 1.0 | 106 ± 0 |

| 131I -OIH | 0.7 ± 0.1 | 0.7 ± 0.1 | 0.2 ± 0.0 | 1.3 ± 0.3 | 0.3 ± 0.1 | 89.1 ± 0.9 | |

| P | 0.0002 | 0.0050 | 0.0413 | 0.0008 | |||

| 99mTc-L- ASMA* | 0.3 ± 0.1 | 0.3 ± 0.0 | 0.0 ± 0.0 | 0.5 ± 0.2 | 0.7 ± 0.3 | 95.1 ± 4.1 | 107 ± 2 |

| 131I -OIH | 0.8 ± 0.1 | 0.6 ± 0.2 | 0.1 ± 0.1 | 1.3 ± 0.3 | 0.7 ± 0.3 | 88.8 ± 2.7 | |

| P | 0.0034 | 0.0061 | 0.0001 | 0.0007 | |||

| 60 min Group B | |||||||

| 99mTc-rac-ASMA* | 17.9 ± 1.1 | 6.2 ± 0.6 | 0.7 ± 0.2 | 4.4 ± 0.6 | 0.6 ± 0.2 | - | - |

| 131I-OIH | 16.7 ± 1.3 | 7.9 ± 0.5 | 0.5 ± 0.2 | 8.9 ± 2.2 | 0.5 ± 0.2 | - | |

| P | 0.0175 | 0.0323 | 0.0189 |

Four rats;

Two rats;

Three rats; Data are presented as mean ± SD.

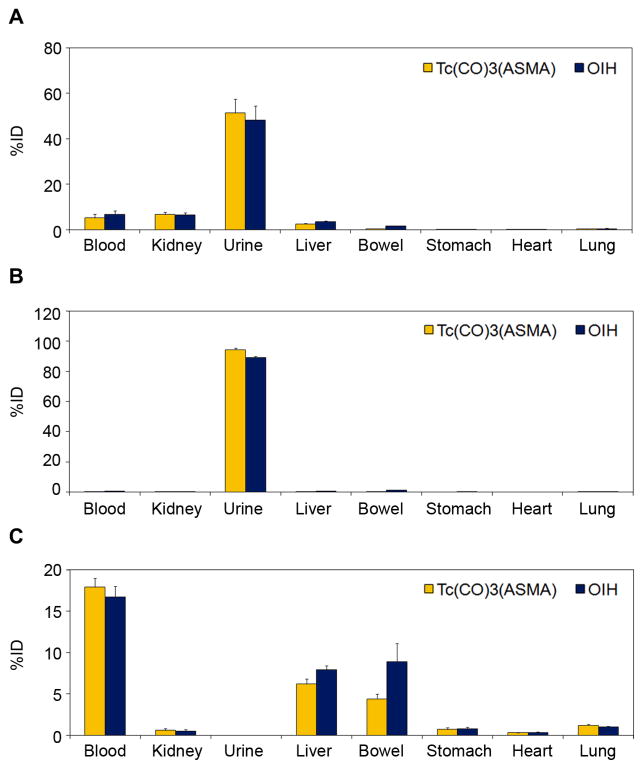

FIGURE 4.

Biodistribution of 99mTc(CO)3(rac-ASMA) and 131I-OIH in normal rats at 10 min (A) and 60 min (B) after injection, and in rats with renal pedicle ligation at 60 min after injection (C), expressed as %ID per organ, blood and urine.

In normal rats, the %ID remaining in the blood at 10 min for both 99mTc(CO)3(ASMA) preparations were similar, 5.2% for rac-ASMA and 4.7% for L-ASMA, and those results were comparable to results obtained with 131I-OIH; P = 0.07. Both 99mTc tracers demonstrated rapid renal extraction and high specificity for renal excretion. The activity of 99mTc tracer in the urine, as a percentage of 131I-OIH, was 106 ± 6% for 99mTc(CO)3(rac-ASMA) and 100 ± 3% for 99mTc(CO)3(L-ASMA) at 10 min, and 106 ± 0% for 99mTc(CO)3(rac-ASMA) and 107 ± 2% for 99mTc(CO)3(L-ASMA) at 60 min, respectively. There was no significant difference in the %ID in the urine for both 99mTc(CO)3(ASMA) preparations and 131I-OIH tracers at 10 min (P > 0.1), although both 99mTc(CO)3(ASMA) tracers were eliminated at a faster rate than 131I-OIH at 60 min (P < 0.001). The %ID in the blood at 60 min ranged from 0.2 to 0.3% for two 99Tc tracers, with both values significantly less than the 0.7–0.8% values obtained with 131I-OIH (P < 0.003) (Table 1). In addition, there was minimal hepatic/gastrointestinal activity with lower uptake of both 99mTc tracers in the liver (P < 0.01) and intestines (P < 0.05) at 60 min when compared to 131I-OIH (Table 1). This low activity is consistent with the highly hydrophilic nature of negatively charged 99mTc complexes at physiological pH as well as with their small size. All other organs (heart, spleen, lungs, stomach) showed negligible uptake of the 99mTc tracers.

Because both 99mTc tracers showed similar tissue/organ biodistribution in normal rats, we evaluated only 99mTc(CO)3(rac-ASMA) in a rat model of renal failure. Biodistribution studies comparing 99mTc(CO)3(rac-ASMA) with 131I-OIH in rats with renal pedicle ligation demonstrated an increase in liver and intestinal activity of both 99mTc and 131I agents at 60 minutes post-injection. However, those increases were significantly higher (P = 0.032 (liver) and P = 0.019 (bowel), respectively) for the 131I tracer indicating that renal failure results in more hepatobiliry excretion or intestinal secretion of 131I-OIH than of 99mTc(CO)3(rac-ASMA) (Table 1 and Fig. 4). In addition, 99mTc(CO)3(rac-ASMA) was significantly better retained in the blood than was 131I-OIH (17.9% vs. 16.7%; P = 0.017).

The renal clearance of 99mTc(CO)3(rac-ASMA) was comparable to that of 131I-OIH (2.85 mL/min/100g vs. 2.97 mL/min/100g, P = 0.481). The clearance value reported in this paper for 131I-OIH was almost identical to those reported by Muller-Suur, 2.76 mL/min/100g (29), Taylor, 2.84 mL/min/100g (30), and Lipowska, 2.96 mL/min/100g (24), when it was measured in similar experiments.

Because these 99mTc tracers are excreted in the urine, we examined the metabolic stability of 99mTc(CO)3(ASMA) by analyzing the urine collected from rats during the first 15 minutes after a bolus injection of 0.5 mCi. Fig. 3 shows typical HPLC chromatograms for 99mTc(CO)3(L-ASMA). As in the parent radiotracer, two 99mTc(CO)3(L-ASMA) diastereomers are clearly evident in the urine radiochromatogram 3C. The elution times of 99mTc(CO)3(L-ASMA) before injection (Fig. 3B) and in the urine (Fig. 3C) are almost identical confirming in vivo stability of both diastereomers of the 99mTc tracer. Very similar results were obtained for 99mTc(CO)3(rac-ASMA).

DISCUSSION

Amino acid analogues, including aminopolycarboxylic acids, have recently been proposed for use as effective chelating ligands for the {M(CO)3}+ core (M = 99mTc, Re) (31–36). Such amino acid analogues can provide three potential coordinating groups positioned to coordinate tridentately and facially to the {M(CO)3}+ center to form stable 99mTc/Re complexes. Our analysis of the charge and charge distribution of the tricarbonyl complexes suggests that a negative inner coordination sphere and an overall dianionic charge at physiological pH favor rapid renal tubular secretion (24, 28, 37). The best example of a 99mTc-tricarbonyl renal tracer meeting these charge requirements and having an aminopolycarboxylate ligand is 99mTc(CO)3(NTA). The renal clearance and timed urine excretion of 99mTc(CO)3(NTA) were comparable to those of 131I-OIH in normal rats (24) and subjects with normal renal function (21) and hepatobiliary excretion was less than that of 131I-OIH in rats with simulated renal failure (24).

ASMA’s chelating ability for 99mTc/Re(CO)3 cores has not been investigated previously. The ligand used here is a geometric isomer of the NTA ligand; one of the carboxymethyl groups is shifted from the central amine atom in NTA to the neighboring alpha carbon in ASMA (Fig. 1). Both ligands have three carboxyl groups and an amine function and can form two five-membered chelate rings with the core. ASMA has the potential to form a five- and a six-membered chelate ring. For either ASMA binding mode, the very hydrophilic ligand should form very stable, dianionic 99mTc/Re(CO)3 complexes having a dangling carboxylate group needed for rapid renal excretion (38).

Ideally, a renal tubular radiopharmaceutical should be designed to exist as a single species at physiologic pH since introduction of a carboxyl group into the ligand core can result in the formation of chelate ring stereoisomers upon 99mTc labeling, each with different pharmacokinetic properties. One of the best examples of this phenomenon is 99mTc-N,N′-bis(mercaptoacetyl)-2,3-diaminopropionate (99mTc-CO2-DADS); in normal volunteers 81% of one isomer was excreted into the urine in 30 min compared with only 18.5% of the second isomer (12). Similarly, we showed that 99mTc-DD-ethylene-dicysteine (99mTc-DD-EC) had a higher clearance than 99mTc-LL-EC in humans (18). These examples clearly show that minor configurational changes can alter the tubular extraction of the radiotracers.

We also demonstrated that both 99mTc-DD- and LL-EC exist in carboxyl ligated monoanionic (20%) and deligated dianionic (80%) forms in rapid equilibrium at physiological pH; these two forms differ distinctly in structure and charge, and almost certainly have different protein binding and tubular receptor affinities. Changes in pH could shift the proportion between the ligated and deligated forms, resulting in a change in clearance which might be interpreted as a change in renal function; also, clearances of these two forms may vary in different disease states.

We demonstrate that our new dianionic 99mTc(CO)3(ASMA) tracer not only has a clearance comparable to that of 131I-OIH but it is also rapidly extracted by the kidney and eliminated in the urine as rapidly as 131I-OIH. The fact that all 99mTc(CO)3(ASMA) stereoisomers exhibit rapid renal extraction is expected because the dangling carboxylate group for each stereoisomer is far from the coordination sphere (unlike 99mTc-CO2-DADS) and there are no possibilities for carboxyl ligated and deligated forms (unlike 99mTc-DD- and LL-EC).

Finally, results obtained from the ligated renal pedicle model show that 99mTc(CO)3(ASMA) is highly specific for renal excretion and actually has less liver and intestinal activity than 131I-OIH. Hepatobiliary elimination of 99mTc-MAG3 has been demonstrated in man (39) and rats (40) and this is likely the mechanism for the increased intestinal activity in our study although it cannot be definitely established from our data. Nevertheless, the high specificity of 99mTc(CO)3(ASMA) for renal excretion is an important feature; if impaired renal function accelerates hepatobiliary elimination, the plasma clearance will overestimate renal function, and gall bladder activity may compromise scan interpretation (39).

CONCLUSION

The ASMA ligand, which binds via two five-membered chelate rings, can be efficiently radiolabeled in high yields with the {99mTc(CO)3}+ core to produce a robust, dianionic 99mTc(CO)3(ASMA) complex. This complex showed pharmacokinetic properties comparable to those of 131I-OIH in normal rats and had less hepatic and intestinal activity than 131I-OIH in an animal model of renal failure. These favorable pharmacokinetic properties warrant studies to determine if 99mTc(CO)3(ASMA) will have pharmacokinetic properties in humans comparable to or superior to those of 99mTc-MAG3 and 131I-OIH.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by the National Institutes of Health grant R37 DK38842. We thank Eugene Malveaux for his excellent technical assistance with all animal studies.

References

- 1.Coresh J, Selvin E, Stevens L, et al. Prevalence of chronic kidney disease in the United States. JAMA. 2007;298:2038–2047. doi: 10.1001/jama.298.17.2038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sarnak MJ, Levey AS, Schoolwerth AC, et al. Kidney disease as a risk factor for development of cardiovascular disease. A Statement from the American Heart Association Councils on Kidney in Cardiovascular Disease, High Blood Pressure Research, Clinical Cardiology, and Epidemiology and Prevention. Circulation. 2003;108:2154–2169. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000095676.90936.80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Stengel B, Tarver-Carr ME, Powe NR, Eberhardt MS, Brancati FL. Lifestyle factors, obesity and the risk of chronic kidney disease. Epidemiology. 2003;14:479–487. doi: 10.1097/01.EDE.0000071413.55296.c4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Anderson S, Halter JB, Hazzard WR, et al. Prediction, progression, and outcomes of chronic kidney disease in older adults. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2009;20:1199–1209. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2008080860. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion. Healthy People 2020. Washington, DC: [Accessed December 20, 2011]. http://www.healthypeople.gov/2020/topicsobjectives2020/overview.aspx?topicid=6. [Google Scholar]

- 6.US Renal Data System (USRDS) [Accessed December 20, 2011];Annual Data Report: Atlas of Chronic Kidney Disease and End-Stage Renal Disease in the United States. 2010 http://www.usrds.org/adr.htm.

- 7.Levey AS, Coresh J, Balk E, et al. National Kidney Foundation practice guidelines for chronic kidney disease: evaluation, classification, and stratification. Ann Intern Med. 2003;139:137–147. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-139-2-200307150-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Blaufox MD, Potchen EJ, Merrill JP. Measurement of effective renal plasma flow in man by external counting methods. J Nucl Med. 1967;8:77–85. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Flannery A, Veber J. Calculation of 131I-ortho-iodohippurate absorbed kidney dose: A literature review. Med Phys. 1980;7:249–250. doi: 10.1118/1.594679. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. [Accessed December 20, 2011];Technetium-99m radiopharmaceuticals: Manufacture of kits. http://www-pub.iaea.org/mtcd/publications/pdf/trs466_web.pdf.

- 11.Alberto R, Schibli R, Egli A, Schubiger AP. A novel organometallic aqua complex of technetium for the labeling of biomolecules: synthesis of [99mTc(OH2)(CO)3]+ from [99mTcO4]− in aqueous solution and its reaction with a bifunctional ligand. J Am Chem Soc. 1998;120:7987–7988. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Klingensmith WC, III, Fritzberg AR, Spitzer VM, et al. Clinical evaluation of Tc-99m N,N′-bis(mercaptoacetyl)-2,3-diaminopropanoate as a replacement for I-131 hippurate. J Nucl Med. 1984;25:42–48. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Taylor A, Eshima D, Fritzberg AR, Christian PE, Kasina S. Comparison of iodine-131 OIH and technetium-99m MAG3 renal imaging in volunteers. J Nucl Med. 1986;27:795–803. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jafri R, Britton K, Nimmon C, et al. Technetium-99m-MAG3, a comparison with iodine-123 and iodine-131-orthoiodohippurate, in patients with renal disorders. J Nucl Med. 1988;29:147–158. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Van Nerom CG, De Bormans GM, De Roo MJ, Vernrugen AM. First experience in healthy volunteers with technetium-99m L,L-ethylenedicysteine, a new renal imaging agent. Eur J Nucl Med. 1993;20:738–746. doi: 10.1007/BF00180902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.O’Malley JP, Ziessman HA, Chantarapitak N. Tc-99m MAG3 as an alternative to Tc-99m DTPA and I-131 Hippuran for renal transplant evaluation. Clin Nucl Med. 1993;18:22–29. doi: 10.1097/00003072-199301000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kabasakal L, Turoglu T, Onsel C, et al. Clinical comparison of technetium-99m-EC, technetium-99m-MAG3 and iodine-131-OIH in renal disorders. J Nucl Med. 1995;36:224–228. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Taylor A, Hansen L, Eshima D, et al. Comparison of technetium-99m-LL-EC isomers in rats and humans. J Nucl Med. 1997;38:821–826. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Taylor AT, Lipowska M, Hansen L, Malveaux E, Marzilli LG. 99mTc-MAEC complexes: new renal radiopharmaceuticals combining characteristics of 99mTc-MAG3 and 99mTc-EC. J Nucl Med. 2004;45:885–891. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lipowska M, He H, Malveaux E, Xu X, Marzilli LG, Taylor A. First evaluation of a 99mTc-tricarbonyl complex, 99mTc(CO)3(LAN), as a new renal radiopharmaceutical in humans. J Nucl Med. 2006;47:1032–1040. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Taylor AT, Lipowska M, Marzilli LG. 99mTc(CO)3(NTA): a 99mTc renal tracer with pharmacokinetic properties comparable to those of 131I-OIH in healthy volunteers. J Nucl Med. 2010;51:391–396. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.109.070813. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Eshima D, Taylor A. Technetium-99m (99mTc) mercaptoacetyltriglycine: Update on the new 99mTc renal tubular function agent. Sem Nucl Med. 1992;22:61–73. doi: 10.1016/s0001-2998(05)80082-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Esteves FP, Taylor A, Manatunga A, Folks R, Krishnan M, Garcia EV. 99mTc-MAG3 renography: normal values for MAG3 clearance and curve parameters, excretory parameters and residual urine volume. Am J Roentgenol. 2006;187:W610–W617. doi: 10.2214/AJR.05.1550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lipowska M, Marzilli LG, Taylor AT. 99mTc(CO)3-nitrilotriacetic acid: a new renal radiopharmaceutical showing pharmacokinetic properties in rats comparable to those of 131I-OIH. J Nucl Med. 2009;50:454–460. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.108.058768. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Maher FT, Tauxe WN. Renal clearance in man of pharmaceuticals containing radioactive iodine. JAMA. 1969;207:97–104. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Maderova J, Pavelicik F, Marek J. N-(Carboxymethyl)aspartic acid. Acta Cryst. 2002;E58:o469–o470. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Snyder RV, Angelici RJ. Stereoselectivity of N-carboxymethyl-amino acid complexes of copper(II) toward optically active amino acids. J Inorg Nucl Chem. 1973;35:523–535. [Google Scholar]

- 28.He H, Lipowska M, Christoforou AM, Marzilli LG, Taylor AT. Initial evaluation of new 99mTc(CO)3 renal imaging agents having carboxyl-rich thioether ligands and chemical characterization of Re(CO)3 analogues. Nucl Med Biol. 2007;34:709–716. doi: 10.1016/j.nucmedbio.2007.06.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Muller-Suur R, Muller-Suur C. Renal and extrarenal handling of a new imaging compound (99m-Tc-MAG3) in the rat. Eur J Nucl Med. 1986;12:438–442. doi: 10.1007/BF00254747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Taylor A, Eshima D. Effects of altered physiological states on clearance and biodistribution of technetium-99m MAG3, iodine-131 OIH, and iodine-125 Iothalamate. J Nucl Med. 1988;29:669–675. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Alberto R, Schibli R, Waibel R, Abram U, Schubiger AP. Basic aqueous chemistry of [M(OH2)3(CO)3]+ (M = Re, Tc) directed towards radiopharmaceutical application. Coord Chem Rev. 1999;190–192:901–919. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Schibli R, Schubiger AP. Current use and future potential of organometallic radiopharmaceuticals. Eur J Nucl Med. 2002;29:1529–1542. doi: 10.1007/s00259-002-0900-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Banerjee SR, Maresca KP, Francesconi L, Valliant J, Babich J, Zubieta J. New directions in the coordination chemistry of 99mTc: a reflection on technetium core structures and a strategy for new chelate design. Nucl Med Biol. 2005;32:1–20. doi: 10.1016/j.nucmedbio.2004.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Liu Y, Pak J-K, Schmutz P, et al. Amino acids labeled with [99mTc(CO)3]+ and recognized by the L-type amino acid transporter LAT1. J Am Chem Soc. 2006;128:15996–15997. doi: 10.1021/ja066002m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bartholomä M, Valliant J, Maresca K, Babich J, Zubieta J. Single amino acid chelates (SAAC): a strategy for the design of technetium and rhenium radiopharmaceuticals. Chem Comm. 2009:493–512. doi: 10.1039/b814903h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lipowska M, He H, Xu X, Taylor AT, Marzilli PA, Marzilli LG. Coordination modes of multidentate ligands in fac-[Re(CO)3(polyaminocarboxylate)] analogues of 99mTc radiopharmaceuticals. Dependence on aqueous solution reaction conditions. Inorg Chem. 2010;49:3141–3151. doi: 10.1021/ic9017568. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lipowska M, Marzilli L, Taylor AT. Impact of charge and pendant carboxyl groups of 99mTc(CO)3 thioether-carboxylate complexes on renal tubular transport [abstract] J Label Compd Radiopharm. 2009;52 (suppl):S473. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Nosco DL, Beaty-Nosco JA. Chemistry of technetium radiopharmaceuticals 1: Chemistry behind the development of technetium-99m compounds to determine kidney function. Coord Chem. 1999;184:91–123. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Rosen JM. Gallbladder uptake simulating hydronephrosis on Tc-99m MAG3 scintigraphy. Clin Nucl Med. 1993;18:713–714. doi: 10.1097/00003072-199308000-00020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Shattuck LA, Eshima D, Taylor A, et al. Evaluation of the hepatobiliary excretion of Tc-99m MAG3 and reconstitution factors affecting the radiochemical purity. J Nucl Med. 1994;35:349–355. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]