Abstract

Evidence suggests inhibition of leukocyte trafficking mitigates, in part, ozone-induced inflammation. In the present study, the authors postulated that inhibition of myristoylated alanine-rich C kinase substrate (MARCKS), an 82-kDa protein with multiple biological roles, could inhibit ozone-induced leukocyte trafficking and cytokine secretions. BALB/c mice (n = 5/cohort) were exposed to ozone (100 ppb) or forced air (FA) for 4 hours. MARCKS-inhibiting peptides, MANS, BIO-11000, BIO-11006, or scrambled control peptide RNS, were intratracheally administered prior to ozone exposure. Ozone selectively enhanced bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) levels of killer cells (KCs; 6 ± 0.9-fold), interleukin-6 (IL-6; 12.7 ± 1.9-fold), and tumor necrosis factor (TNF; 2.1 ± 0.5-fold) as compared to cohorts exposed to FA. Additionally, ozone increased BAL neutrophils by 21% ± 2% with no significant (P > .05) changes in other cell types. MANS, BIO-11000, and BIO-11006 significantly reduced ozone-induced KC secretion by 66% ± 14%, 47% ± 15%, and 71.1% ± 14%, and IL-6 secretion by 69% ± 12%, 40% ± 7%, and 86.1% ± 11%, respectively. Ozone-mediated increases in BAL neutrophils were reduced by MANS (86% ± 7%) and BIO-11006 (84% ± 2.5%), but not BIO-11000. These studies identify for the first time the novel potential of MARCKS protein inhibitors in abrogating ozone-induced increases in neutrophils, cytokines, and chemokines in BAL fluid. BIO-11006 is being developed as a treatment for chronic obstructive pulmonary disorder (COPD) and is currently being evaluated in a phase 2 clinical study.

Keywords: asthma, BIO-11006, COPD, cytokines, inflammation, MANS peptide

Ozone as a common environmental toxin enhances leukocyte trafficking, airway inflammation, and hyperresponsiveness [1]. Ozone comes in contact with both airway resident structural cells and trafficking immune cells, and consequently induces cytokine and prostaglandin secretion in both cell types [2, 3]. After ozone exposure, airway inflammation, tissue injury, and altered bronchomotor tone are associated with enhanced immune cell numbers in bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) fluid [4]. Across species, consistent elevation of polymorphonuclear (PMN) cells in BAL fluid is a common indicator of ozone-induced inflammation [5]. In addition to inflammation, neutrophils also modulate airway sensitivity; antibody-mediated depletion of neutrophils reduces airway hyperresponsiveness [6]. Taken together, these data suggest that modulating leukocyte trafficking could inhibit ozone-induced inflammation.

Recent studies have identified therapeutic benefits of myristoylated alanine-rich C kinase substrate (MARCKS) inhibitory peptides in attenuating multiple pathophysiological outcomes associated with chronic airway inflammation. MARCKS, an 82-kDa protein expressed in multiple airway cell types, is a ubiquitous substrate for the family of protein kinase C (PKC) enzymes and proline-directed kinases such as mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) and Cdks [7, 8]. MARCKS protein has 3 evolutionary conserved domains including the N-terminus, the multiple homology 2 domain, and the phosphorylation site domain [9]. The N-terminus anchors MARCKS to the cell membrane and interacts with downstream intracellular molecules, such as calcium-calmodulin and negatively charged membrane phospholipids [10, 11]. Evidence suggests that competitive inhibition of the membrane binding site of the native MARCKS by MANS curtails mucin release in murine airways after allergen exposure [12]. MARCKS protein inhibition also substantially curtails phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate (PMA)-induced neutrophil degranulation and myeloperoxidase release [13]. In human leukocytes, MARCKS inhibitory peptides substantially curtail secretion of eosinophil peroxidase, lysozyme, and granzyme from membrane-bound granules [13]. Because mucous production is enhanced in the presence of neutrophil-derived mediators including cytokines, chemokines, prostanoids, and elastases [14], and inhibition of MARCKS protein effectively abrogates both epithelial mucous secretion and neutrophil function/migration, we hypothesized that the MARCKS inhibitory peptides could offer a unique therapeutic approach to inhibit ozone-induced airway neutrophil migration and inflammation.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Ozone exposure and treatments

Experiments were performed on mice between 6 and 7 weeks of age. Mice used in this study were housed under pathogen-free conditions and received water and food ad libitum. All protocols were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of the University of Pennsylvania. Healthy mice were intratracheally (i.t.) injected with 25 μL of MARCKS inhibitor peptides, MANS (myristic acid–GAQFSKTAAKGEAAAERPGEAAVA), BIO-11000 (myristoyl-GAQFSKTAAKOH), BIO-11006 (acetyl-GAQFSKTAAKOH), or scrambled RNS (myristic acid GTAPAAEGAGAEVKRASAEAKQAF) peptides [15, 16] at a concentration of 1 mM. Mice in control groups were injected with 25 μL of phosphate-buffered saline (PBS).

Mice were then placed in cages inside a 160-L Plexiglas ozone exposure chamber (Mitchell Plastic, Norton, OH). Air was renewed within the chamber at the rate of 20 changes/hour, with 50% to 60% relative humidity and a temperature of 20°C to 22°C. Ozone was generated by directing an air source through an AQUA-FLO ozone generator (model CD05; Aqua-Flo, Baltimore, MD), upstream of the exposure chamber. The ozone-oxygen mixture was metered into the inlet air stream, and ozone concentrations were monitored continuously within the chamber with an ozone monitor (model 202; 2B Technologies, Golden, CO). Groups of mice (n = 5) were exposed to 100 ppb ozone for 4 hours during which time they did not have access to food and water. The control mice received forced air and were deprived of food and water for 4 hours. The ozone concentrations in the study were selected after extensive dose-response studies to ensure that the exposure (i.e., 100 ppb for 4 hours) was adequate to induce an airway inflammatory response without eliciting immediate respiratory distress [17]. Further, the ozone concentrations used in this study are physiologically relevant and comparable to those measured environmentally in US cities.

Differential cell count

As previously described, BAL was performed after 1 hour of recovery after ozone treatment [17]. Briefly, mice were euthanized with an intraperitoneal injection of a mixture of ketamine and xylazine (100 and 20 mg/kg, respectively). A tracheotomy was performed, and the trachea was cannulated with a 20-gauge blunt end needle. Bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) was performed using 0.7 ml and twice with 1 mL sterile PBS. The recovered BAL fluid from 3 lavages was pooled. Pooled BAL fluid was centrifuged at 4°C for 10 minutes at 400 × g, and the cell pellet was resuspended in 1 mL of PBS. Total cell counts were determined from an aliquot of the cell suspension. Differential cell counts were done on cytocentrifuge preparations (Cytospin 3; Thermo Shandon, Pittsburgh, PA) stained with Kwik-Diff (Thermo Shandon, Pittsburgh, PA), and 200 to 500 cells were counted from each individual.

Tissue fixation and staining

After sacrifice, the left lung lobes were perfused with 10% neutral-buffered formalin containing phosphatase inhibitor cocktail (200 mM sodium fluoride and 200 mM sodium pervanadate), placed in a fixative for approximately 24 hours, stained for hematoxylin and eosin (H&E), and evaluated by light microscopy.

Semiquantitative analysis of inflammation

Histopathological analysis of inflammatory cell infiltration in the lung tissues was evaluated according to a modification of the method [18] using a Nikon eclipse 80i microscope (Nikon, Tokyo, Japan). The magnitude of peribronchial inflammation was scored on a semiquantitative scale: 0, normal; 1, few cells; 2, inflammatory cells 1 cell layer deep; 3, inflammatory cells 2 to 4 cell layers deep; 4, inflammatory cells of >4 cell layers deep. Score for each mouse was calculated from a total of 15 airways in 5 to 7 tissue sections. The specimens were evaluated independently by 2 experienced investigators and an average score was reported.

Cytokine assays

Murine cytokine and chemokine concentrations, including tumor necrosis factor (TNF), interferon (IFN)-γ, interleukin (IL)-6, and killer cell (KC), were determined in BAL fluid using specific kits from R&D Systems (Minneapolis, MN). The assays were performed according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

Cell viability assays

Viability assay of cells in BAL fluid was performed with trypan blue exclusion. Briefly, cells were pelleted and resuspended in 1 mL Dulbecco’s modified Eagle medium (DMEM)/10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) and maintained for up to 24 hours in culture. Cell suspensions (20 μL) were mixed with 20 μL of 4% trypan blue solution and incubated for 1 minute before counting in a hemocytometer. Data were expressed as percent nonviable cells.

Data analysis

Results are presented as mean ± SEM (n = 5–12 for each point, for enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays [ELISAs]). Significance levels were calculated using 1-way analysis of variance (ANOVA), followed by the Scheffe test, using SPSS 6.1 software (Cary, NC). P < .05 was considered significant.

RESULTS

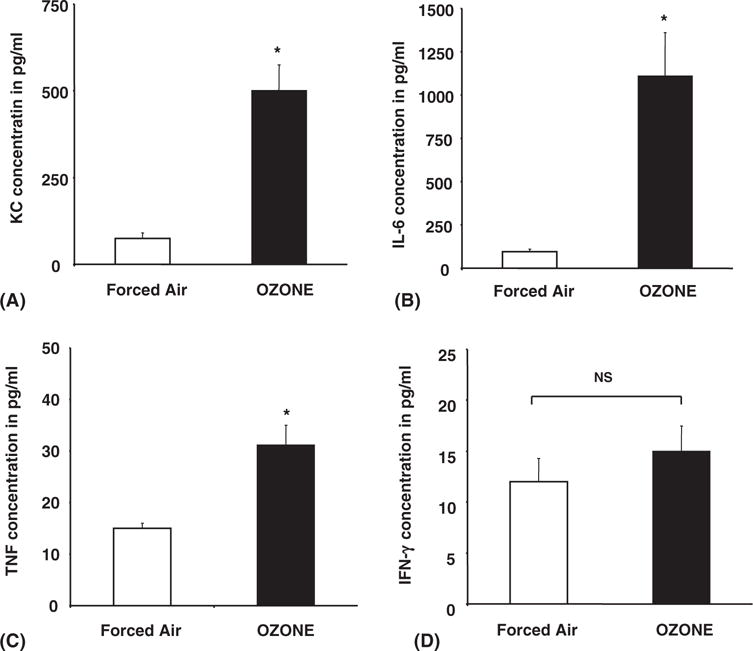

Ozone differentially regulates cytokine secretions in murine airways

In murine models, enhanced expression of cytokines, including IL-5, IL-6, TNF, granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor (GM-CSF), IFN, and KC/IL-8, serves as biomarkers of airway inflammation. As demonstrated in Figure 1A to D, ozone exposure at 100 ppb ozone for 4 hours significantly (P < .05) enhanced KC (6 ± 0.9-fold, 445 ± 70 pg/mL), IL-6 (12.7 ± 1.9-fold, 1215 ± 185 pg/mL), and TNF (2.1 ± 0.5-fold, 15 ± 1 pg/mL) secretion in BAL fluids over cohorts exposed to filtered air (FA). In contrast, comparative evaluation of BAL fluid from FA- or ozone-exposed groups showed no detectable changes in IFN secretion (P > .05).

FIGURE 1.

Ozone differentially induces cytokine secretions in mice. Mice were exposed to ozone (100 ppb) or forced air for 4 hours. After 1 hour of recovery time, the mice were sacrificed, and cytokine concentration was then determined in BAL fluid by ELISA for KC (A), IL-6 (B), TNF (C) and IFN-γ (D). Each cohort consisted of 5 mice, and BAL fluid obtained from each mouse was performed in triplicate as described in Materials and Methods. Data represent mean ± SEM from 3 separate experiments. *Significantly different from FA when P < .05 by ANOVA.

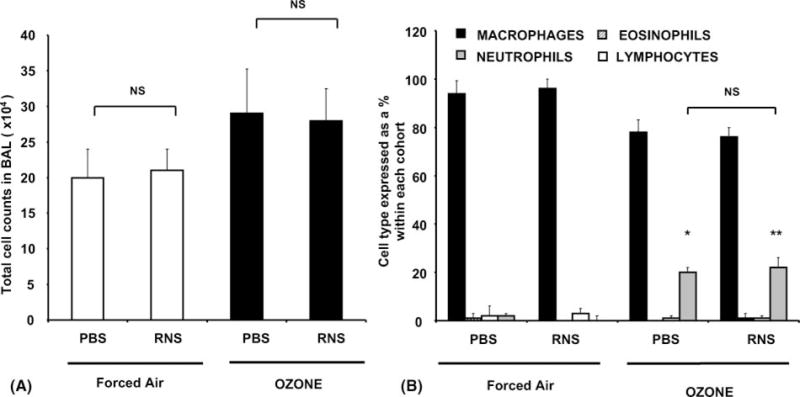

Ozone exposure selectively increases neutrophils in the bal

As represented in Figure 2A and B, compared to mice exposed to forced air, ozone exposure significantly (P < .05) increased total cell counts by 107,700 ± 213,600 (56%) in PBS- and by 89,750 ± 154,500 (45%) in RNS-administered cohorts, respectively. Evaluation of constitutive cell populations in PBS-and RNS-instilled groups showed a selective and comparable increase in neutrophils by 20.5% ± 1% and 21% ± 2% after ozone exposure. Estimation of other cell types, including macrophages, eosinophils, or lymphocytes, in BAL fluid revealed no significant ozone-mediated changes.

FIGURE 2.

Ozone exposure specifically increases neutrophil cell counts in BAL. Cohorts of 5 mice were exposed to ozone (100 ppb) or forced air for 4 hours. After 1 hour of recovery time, the mice were sacrificed and lavaged with sterile PBS as described in Materials and Methods. (A) Total cell numbers in BAL fluid in cohorts exposed to forced air or ozone after administration of diluent/PBS or scrambled peptide, RNS. (B) Differential cell counts expressed as a percent of total cell numbers within each cohort. Data represent group mean ± SEM from three separate experiments. *’ **Significantly different from FA when P < .05 by ANOVA.

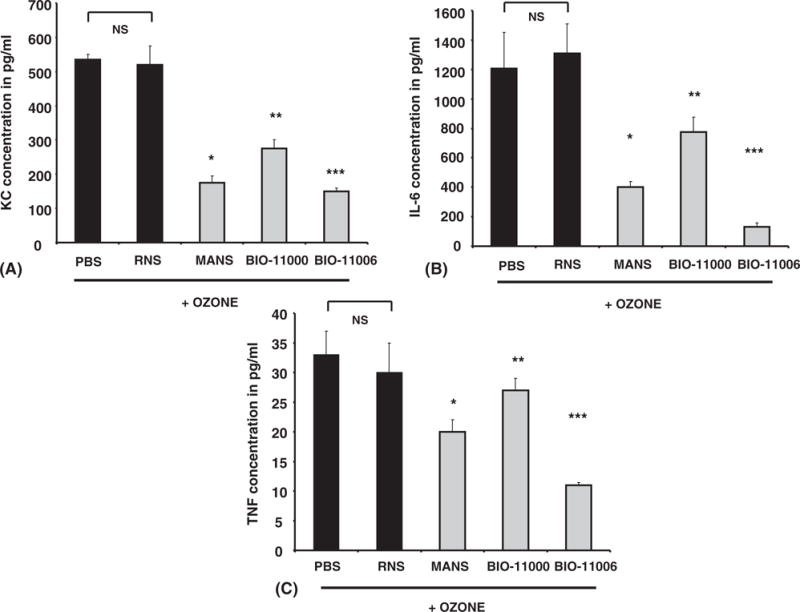

Inhibition of marcks protein inhibits ozone-induced cytokine secretions

As shown in Figure 3, i.t. instillation of MANS, BIO-11000, or BIO-11006 significantly inhibited (P < .05) ozone-induced secretion of KCs by 66% ± 14%, 47% ± 15%, and 71.1% ± 14%, respectively, over mice treated with RNS peptide. Similarly, ozone-mediated IL-6 secretion was also inhibited by 69% ± 12%, 40% ± 7%, and 86.1% ± 11% in cohorts treated by MANS, BIO-11000, and BIO-11006, respectively. However, only MANS and BIO-11006, but not BIO-11000, inhibited TNF secretions in BAL fluids by 33% ± 10% and 60% ± 4%, respectively.

FIGURE 3.

MARCKS protein inhibitors attenuate ozone-induced cytokine enhancement in mice. Mice were i.t. injected with PBS, RNS, MANS, BIO-11000, or BIO-11006 and exposed to ozone (100 ppb) for 4 hours. Each cohort consisted of 5 mice, and BAL fluid obtained from each mouse was assessed in triplicate for KC (A), IL-6 (B), and TNF (C) by ELISA. MANS, BIO-11000, and BIO-11006 had no effect on KC, TNF, IL-6, or IFN-γ levels in animals treated with forced air (data not shown). Data represents group mean ± SEM from 3 separate experiments. *,**,***Significantly different from RNS when P < .05 by ANOVA.

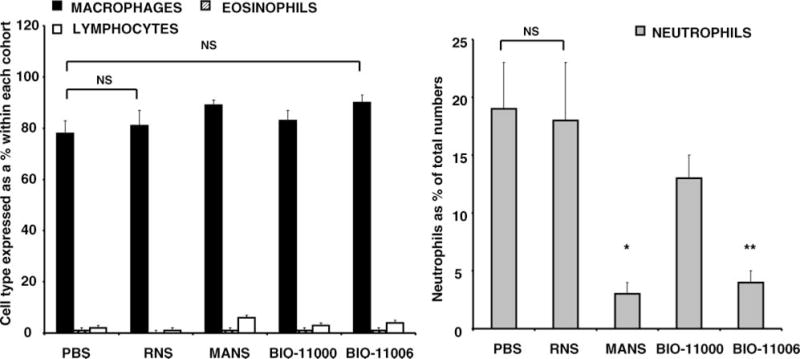

Marcks inhibition decreases ozone-induced increases in bal fluid neutrophils

As shown in Figure 4A and B, i.t. administration of MANS or BIO-11006 peptide prior to ozone exposure inhibited neutrophil cell counts by 86% ± 7% and 84% ± 3%, respectively, as compared with RNS-treated cohorts. Administration of either MANS or BIO-11006 showed no significant effect on ozone-mediated increases in macrophage, eosinophil, or lymphocyte numbers in BAL fluid. In parallel studies, BIO-11000 had little effect on ozone-induced neutrophil numbers in BAL fluid.

FIGURE 4.

MANS and BIO-11006 substantially abrogate ozone-induced neutrophilia. After i.t. instillation of PBS, RNS, MANS, BIO-11000, or BIO-11006, mice were exposed to ozone for 4 hours. Cell counts were performed for neutrophils, macrophages, eosinophils, and lymphocytes in BAL fluid. Data in the figure are representative of mean cell counts ± SEM from 3 separate experiments with each experimental group containing 5 animals. *,**Significantly different from RNS when P < .05 by ANOVA.

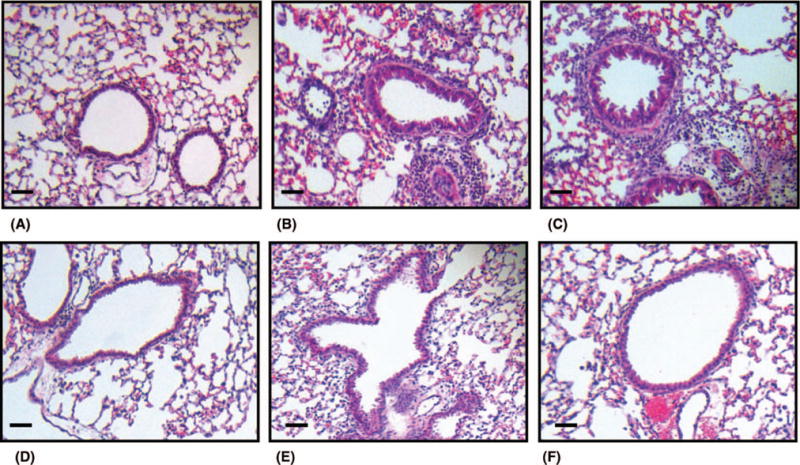

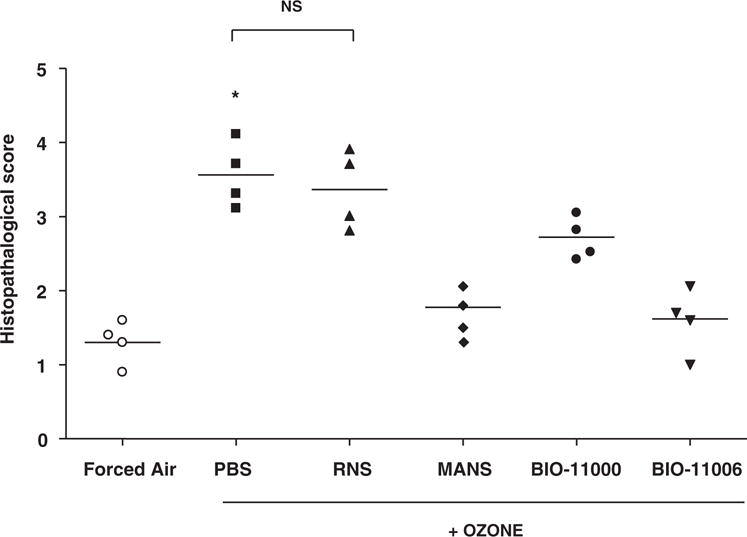

Marcks protein inhibition reduces ozone-induced airway inflammation

As conveyed in Figure 5B, ozone induces peribronchial infiltration of leukocytes in hematoxylin and eosin (H&E)-stained sections from lungs of PBS-administered mice. Consistent with the ability of MANS and BIO-11006 peptides to reduce ozone-mediated neutrophils in BAL fluid, leukocyte numbers were also decreased in the submucosa of the bronchi, as was evident in H&E-stained lung sections. Confirming the specificity of MARCKS protein inhibition in reducing ozone-induced immune cell numbers, scrambled peptide (RNS) showed little effect on peribronchial infiltrates induced by ozone. Semiquantitative analysis and grading in H&E sections substantiated the role of MANS and BIO-11006 in inhibiting ozone-induced peribronchial inflammation (Figure 6). Histological examination of airways and analysis of BAL fluid revealed no evidence of apoptosis or necrosis after i.t. instillation of any peptide (data not shown).

FIGURE 5.

Representative lung histology of ozone-induced immune cell influx in murine lungs. H&E staining of left lung sections from mice following (A) i.t. PBS instillation and exposure to forced air and (B) i.t. PBS administration followed by ozone exposure at 100 ppb. (C) After ozone exposure, maximal infiltration of leukocytes was observed in the submucosa of mice intratracheally administered with RNS peptide and was comparable to that observed in PBS-instilled mice (B). Differential effects of MARCKS inhibitory peptides, MANS (D), BIO-11000 (E), and BIO-11006 (F), abrogated ozone-induced leukocyte migration in the submucosa. All sections were magnified 200×, and the scale bar (lower left corner of all figures) denotes 50 μm. The lungs of 5 mice from each treatment group were processed for histology, and results shown are representative of each group.

FIGURE 6.

MARCKS peptide inhibitors attenuate ozone-induced inflammation. H&E-stained lung tissue sections from ozone-exposed animals treated with or without PBS, RNS, MANS, BIO-11000, and BIO-11006 were graded for immune cell infiltration following histopathological parameters described in Materials and Methods. Each point is representative of the mean score per animal calculated from a total of 15 airways in 5 to 7 tissue sections. Data are shown as individual values, and each horizontal line indicates the mean value per group (n = 4 animals). *Significantly different from the FA-exposed animals at P < .05.

DISCUSSION

In this study, we report that i.t. instillation of MARCKS inhibitory peptides, MANS and BIO-11006, attenuates ozone-mediated increases in BAL neutrophils and proinflammatory cytokine levels. Our findings were further confirmed in lung tissue sections where MARCKS protein inhibitors reduced ozone-mediated peribronchial influx of immune cells. Although earlier studies have reported on the therapeutic benefits of MARCKS protein inhibitors as a means to resolve mucous hypersecretion and airway obstruction in murine airways, our study is the first to investigate their beneficial role in mitigating ozone-induced airway inflammation [12].

Airway inflammation is an integrated and dynamic response modulated by resident structural cells and trafficking leukocytes via cell-cell interactions or secretions of soluble mediators. Studies have shown the importance of both structural cells and leukocytes in mediating ozone-induced inflammation, airway hyperresponsiveness and tissue injury. In the context of airway structural cells, ozone induces cyclooxygenase (COX) and 15-lipoxygenase (LO) metabolites that, in turn, modulate cytokine secretion, increase epithelial permeability and enhance leukocyte trafficking in response to chemotactic factors [19]. Accordingly, ozone-induced levels of cytokines and chemokines correlate with increased leukocyte numbers including neutrophils, eosinophils, and macrophages [20].

After injury, airway neutrophil accumulation in concert with increased levels of chemokines is a characteristic feature of allergen- or ozone-induced lung inflammation. Previous in vivo studies in murine models show maximal polymorphonuclear neutrophil (PMN) migration occurs 4 to 6 hours after ozone exposure [21, 22]. Tosi et al. demonstrated that ozone exposure of primary epithelial cells enhances binding of PMNs to epithelial cells [23]. Similarly, PMNs recovered in BAL fluid of ozone-exposed guinea pigs were maximal at 3 to -6 hours after ozone exposure and remained elevated for 3 days [24]. Increased adhesion between epithelial cells and PMNs was attributed to enhanced expression of intercellular adhesion molecules (ICAMs) and counter-receptors for CD11/CD18 integrins on PMNs [25]. Comprehensive analysis of gene transcription in lungs after ozone exposure demonstrated substantial inhibition of angiopoietin-1 (ANGPT1) expression [26]. ANGPT1 reduces neutrophil migration in in vivo and in vitro studies, and inhibition of ANGPT1 enhances neutrophil chemotaxis in response to IL-6 and IL-8 [27]. Plausibly, a similar mechanism could enhance ozone-induced neutrophil numbers in BAL fluid in our study.

In addition to enhanced airway permeability and neutrophil recruitment, ozone-mediated airway inflammatory responses are characterized by activation of neutrophils manifested by the release of a variety of mediators. Activated neutrophils secrete a wide variety of proinflammatory cytokines, prostanoids, proteases, reactive oxygen species, myeloperoxidase (MPO), and matrix metalloproteinase-9 (MMP-9) [28]. Accordingly, ozone-induced increases in levels of cytokines such as TNF and IL-6 or chemokine KCs were also observed in our studies. Bhalla et al. also demonstrated that ozone concomitantly enhances PMN numbers and cytokines such as TNF, IL-10, and IL-6 in BAL fluid [5].

Apart from an ozone-induced increase in neutrophils, no significant increases in other immune cell types, including macrophages, lymphocytes, or eosinophils, were detected. This finding is consistent with previous reports in C57BL/6 mice where enhanced neutrophil numbers overlapped with decreased macrophages after 4 hours of ozone exposure. Interestingly, macrophage levels returned to normal levels at 48 hours, and increased at 72 hours after exposure, suggesting that ozone-induced macrophage infiltration is a late response to ozone-induced airway injury [29]. Contradictions exist regarding the role of macrophages in ozone-induced airway inflammation. Experimental inhalation of ozone in human volunteers increased macrophages, IL-6, and IL-8 in BAL fluid [30]. Alternatively, diminished numbers of macrophages have been reported in rabbit, human, and rat models after ozone inhalation [1, 31, 32]. Finally Hotchkiss et al. reported modest changes in macrophage numbers after 3 and 18 hours of ozone inhalation [33]. Although the precise mechanisms explaining these disparate findings remain unclear, investigators speculate that enhanced adherence of macrophages to alveolar walls or increased fragility of macrophages after ozone exposure could, in part, explain the disparity in BAL macrophage composition reported in those studies.

Ozone-mediated airway neutrophil localization is modulated by diverse regulatory mechanisms, and neutrophil depletion ameliorates ozone-induced airway injury in rats [34]. For instance, impairment of TNF signaling or complement activation significantly attenuates neutrophil recruitment to the airspaces following ozone exposure [35, 36]. Similarly, neutralizing antibodies to IP-10, KC/IL-8, and monocyte chemoattractant protein (MCP)-3 also deplete ozone-mediated airway neutrophilia in murine studies [37]. Contrary to the effects of macrolides in minimizing airway neutrophilia in multiple species, azithromycin administration has little effect on altering ozone-induced BAL fluid neutrophils [38]. In a recent study, the unprecedented ability of a novel 24–amino acid peptide (MANS, homologous to N-terminal of MARCKS protein) to substantially inhibit fMLF-(N-formyl-methionyl-leucyl-phenylalanine)–mediated neutrophil migration in vitro has been reported [39]. Using the same peptide or its structural analog BIO-11006, we showed that these molecules substantially diminished ozone-mediated neutrophil recruitment with little change in the number of other immune cells. The precise mechanism by which MANS and BIO-11006 modulate neutrophil migration remains unclear. However, based on collective findings from other studies using multiple cell types, it appears that MARCKS protein may interact with PKC- and calmodulin-dependent signaling cascades to inhibit actin cytoskeleton-plasma membrane interactions essential for cell motility [40].

Another important finding in our study is the ability of MARCKS protein inhibitors to diminish ozone-induced cytokine secretion. Both MANS and BIO-11006 attenuated ozone-induced neutrophils in BAL fluid and reduced IL-6, KC, and TNF levels. Both neutrophils and epithelial cells are prominent sources of cytokines such as IL-8 and TNF [41, 42]. Although inhibition of MARCKS protein in either cell type has been demonstrated to alter biological function [13, 15], to date, the exclusive role of MARCKS protein in mediating cytokine secretion remains unknown. Based on our findings, we speculate that MARCKS inhibitors likely mitigated neutrophil chemotaxis by inhibiting epithelium-derived KCs. Alternatively, it is also equally plausible that decreases in KC levels in BAL fluid after MARCKS inhibition is a result of fewer neutrophils migrating into alveolar airspaces after ozone exposure.

Neutrophilic airway inflammation is a predominant feature associated with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) and correlates with disease severity. Increased neutrophil numbers in the airways could be explained by increased influx or prolonged survival of neutrophils [43]. Further, neutrophil depletion ameliorates ozone-induced airway injury in rats [34]. Earlier studies in a mouse model of asthma revealed a therapeutic potential for MARCKS inhibitors in reducing mucin secretion and improving airway obstruction [12]. Our study for the first time demonstrates the unique capacity of the BIO-11006 and MANS peptides to inhibit ozone-induced neutrophil numbers and cytokine secretions in BAL fluid. Besides directly diminishing neutrophil-mediated inflammation, MARCKS protein inhibitors can have therapeutic potential in ozone-induced exacerbation of allergic asthma. For instance, ozone exposure can increase allergen-induced airway responses in patients with asthma [44]. In allergic rat models, ozone enhances airway hyperresponsiveness (AHR), mucous cell metaplasia, and BAL fluid leukocyte, cytokine, and leukotriene levels [17, 45]. Similarly, antibody-mediated neutrophil depletion diminishes AHR, and conditional transgenic overexpression of neutrophil chemoattractants, enhances allergic responses. In murine models of asthma, ozone exposure enhances airway remodeling via critical association of neutrophils and eosinophils [46][34] J.G. Wagner, J.A. Hotchkiss and J.R. Harkema, Enhancement of nasal inflammatory and epithelial responses after ozone and allergen coexposure in Brown Norway rats, Toxicol. Sci. 67 (2002), pp. 284–294. Full Text via CrossRef &pipe; View Record in Scopus &pipe; Cited By in Scopus (18). Based on current evidence emphasizing the critical role of neutrophils in allergic rat models and potential to attenuate airway neutrophilia, MANS peptide or its synthetic analog BIO-11006 may have therapeutic value in managing ozone-induced exacerbations of asthma or COPD.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences grant ES013508 and National Institutes of Health/National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute grant R01 HL080676. The authors acknowledge Mary McNichol for expert assistance in preparation of the manuscript.

Footnotes

Declaration of interest: The authors report no conflicts of interest. The authors alone are responsible for the content and writing of the paper.

References

- 1.Koren HS, Devlin RB, Graham DE, Mann R, McGee MP, Horstman DH, Kozumbo WJ, Becker S, House DE, Mc-Donnell WF, et al. Ozone-induced inflammation in the lower airways of human subjects. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1989;139:407–415. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm/139.2.407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Devlin RB, McKinnon KP, Noah T, Becker S, Koren HS. Ozone-induced release of cytokines and fibronectin by alveolar macrophages and airway epithelial cells. Am J Physiol. 1994;266:L612–L619. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.1994.266.6.L612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Damera G, Zhao H, Wang M, Smith M, Kirby C, Jester WF, Lawson JA, Panettieri RA., Jr Ozone modulates IL-6 secretion in human airway epithelial and smooth muscle cells. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2009;296:L674–L683. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.90585.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fabbri LM, Aizawa H, Alpert SE, Walters EH, O’Byrne PM, Gold BD, Nadel JA, Holtzman MJ. Airway hyperresponsiveness and changes in cell counts in bronchoalveolar lavage after ozone exposure in dogs. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1984;129:288–291. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bhalla DK, Reinhart PG, Bai C, Gupta SK. Amelioration of ozone-induced lung injury by anti-tumor necrosis factor-alpha. Toxicol Sci. 2002;69:400–408. doi: 10.1093/toxsci/69.2.400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Park SJ, Wiekowski MT, Lira SA, Mehrad B. Neutrophils regulate airway responses in a model of fungal allergic airways disease. J Immunol. 2006;176:2538–2545. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.176.4.2538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Arbuzova A, Schmitz AA, Vergeres G. Cross-talk unfolded: MARCKS proteins. Biochem J. 2002;362:1–12. doi: 10.1042/0264-6021:3620001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Blackshear PJ. The MARCKS family of cellular protein kinase C substrates. J Biol Chem. 1993;268:1501–1504. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Aderem AA, Albert KA, Keum MM, Wang JK, Greengard P, Cohn ZA. Stimulus-dependent myristoylation of a major substrate for protein kinase C. Nature. 1988;332:362–364. doi: 10.1038/332362a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Aderem A. The MARCKS brothers: a family of protein kinase C substrates. Cell. 1992;71:713–716. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(92)90546-o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Matsubara M, Titani K, Taniguchi H, Hayashi N. Direct involvement of protein myristoylation in myristoylated alanine-rich C kinase substrate (MARCKS)-calmodulin interaction. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:48898–48902. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M305488200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Agrawal A, Rengarajan S, Adler KB, Ram A, Ghosh B, Fahim M, Dickey BF. Inhibition of mucin secretion with MARCKS-related peptide improves airway obstruction in a mouse model of asthma. J Appl Physiol. 2007;102:399–405. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00630.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Takashi S, Park J, Fang S, Koyama S, Parikh I, Adler KB. A peptide against the N-terminus of myristoylated alanine-rich C kinase substrate inhibits degranulation of human leukocytes in vitro. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2006;34:647–652. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2006-0030RC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rose MC, Voynow JA. Respiratory tract mucin genes and mucin glycoproteins in health and disease. Physiol Rev. 2006;86:245–278. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00010.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Singer M, Martin LD, Vargaftig BB, Park J, Gruber AD, Li Y, Adler KB. A MARCKS-related peptide blocks mucus hypersecretion in a mouse model of asthma. Nat Med. 2004;10:193–196. doi: 10.1038/nm983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Li Y, Martin LD, Spizz G, Adler KB. MARCKS protein is a key molecule regulating mucin secretion by human airway epithelial cells in vitro. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:40982–40990. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M105614200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kierstein S, Krytska K, Sharma S, Amrani Y, Salmon M, Panettieri RA, Jr, Zangrilli J, Haczku A. Ozone inhalation induces exacerbation of eosinophilic airway inflammation and hyperresponsiveness in allergen-sensitized mice. Allergy. 2008;63:438–446. doi: 10.1111/j.1398-9995.2007.01587.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Myou S, Leff AR, Myo S, Boetticher E, Tong J, Meliton AY, Liu J, Munoz NM, Zhu X. Blockade of inflammation and airway hyperresponsiveness in immune-sensitized mice by dominant-negative phosphoinositide 3-kinase-TAT. J Exp Med. 2003;198:1573–1582. doi: 10.1084/jem.20030298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Leikauf GD, Driscoll KE, Wey HE. Ozone-induced augmentation of eicosanoid metabolism in epithelial cells from bovine trachea. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1988;137:435–442. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm/137.2.435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Leikauf GD, Simpson LG, Santrock J, Zhao Q, Abbinante-Nissen J, Zhou S, Driscoll KE. Airway epithelial cell responses to ozone injury. Environ Health Perspect. 1995;103(Suppl 2):91–95. doi: 10.1289/ehp.95103s291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hyde DM, Hubbard WC, Wong V, Wu R, Pinkerton K, Plopper CG. Ozone-induced acute tracheobronchial epithelial injury: relationship to granulocyte emigration in the lung. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 1992;6:481–497. doi: 10.1165/ajrcmb/6.5.481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kleeberger SR, Hudak BB. Acute ozone-induced change in airway permeability: role of infiltrating leukocytes. J Appl Physiol. 1992;72:670–676. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1992.72.2.670. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tosi MF, Hamedani A, Brosovich J, Alpert SE. ICAM-1-independent, CD18-dependent adhesion between neutrophils and human airway epithelial cells exposed in vitro to ozone. J Immunol. 1994;152:1935–1942. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Schultheis AH, Bassett DJ. Inflammatory cell influx into ozone-exposed guinea pig lung interstitial and airways spaces. Agents Actions. 1991;34:270–273. doi: 10.1007/BF01993300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cheek JM, McDonald RJ, Rapalyea L, Tarkington BK, Hyde DM. Neutrophils enhance removal of ozone-injured alveolar epithelial cells in vitro. Am J Physiol. 1995;269:L527–L535. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.1995.269.4.L527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Williams AS, Issa R, Leung SY, Nath P, Ferguson GD, Bennett BL, Adcock IM, Chung KF. Attenuation of ozone-induced airway inflammation and hyper-responsiveness by c-Jun NH2 terminal kinase inhibitor SP600125. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2007;322:351–359. doi: 10.1124/jpet.107.121624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Witzenbichler B, Westermann D, Knueppel S, Schultheiss HP, Tschope C. Protective role of angiopoietin-1 in endotoxic shock. Circulation. 2005;111:97–105. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000151287.08202.8E. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bosson J, Pourazar J, Forsberg B, Adelroth E, Sandstrom T, Blomberg A. Ozone enhances the airway inflammation initiated by diesel exhaust. Respir Med. 2007;101:1140–1146. doi: 10.1016/j.rmed.2006.11.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zhao Q, Simpson LG, Driscoll KE, Leikauf GD. Chemokine regulation of ozone-induced neutrophil and monocyte inflammation. Am J Physiol. 1998;274:L39–L46. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.1998.274.1.L39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Arjomandi M, Witten A, Abbritti E, Reintjes K, Schmidlin I, Zhai W, Solomon C, Balmes J. Repeated exposure to ozone increases alveolar macrophage recruitment into asthmatic airways. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2005;172:427–432. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200502-272OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Driscoll KE, Vollmuth TA, Schlesinger RB. Acute and subchronic ozone inhalation in the rabbit: response of alveolar macrophages. J Toxicol Environ Health. 1987;21:27–43. doi: 10.1080/15287398709531000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Pino MV, Levin JR, Stovall MY, Hyde DM. Pulmonary inflammation and epithelial injury in response to acute ozone exposure in the rat. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. 1992;112:64–72. doi: 10.1016/0041-008x(92)90280-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hotchkiss JA, Harkema JR, Kirkpatrick DT, Henderson RF. Response of rat alveolar macrophages to ozone: quantitative assessment of population size, morphology, and proliferation following acute exposure. Exp Lung Res. 1989;15:1–16. doi: 10.3109/01902148909069605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bassett D, Elbon-Copp C, Otterbein S, Barraclough-Mitchell H, Delorme M, Yang H. Inflammatory cell availability affects ozone-induced lung damage. J Toxicol Environ Health A. 2001;64:547–565. doi: 10.1080/15287390152627237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Cho HY, Zhang LY, Kleeberger SR. Ozone-induced lung inflammation and hyperreactivity are mediated via tumor necrosis factor-alpha receptors. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2001;280:L537–L546. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.2001.280.3.L537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Park JW, Taube C, Joetham A, Takeda K, Kodama T, Dakhama A, McConville G, Allen CB, Sfyroera G, Shultz LD, Lambris JD, Giclas PC, Holers VM, Gelfand EW. Complement activation is critical to airway hyperresponsiveness after acute ozone exposure. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2004;169:726–732. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200307-1042OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Michalec L, Choudhury BK, Postlethwait E, Wild JS, Alam R, Lett-Brown M, Sur S. CCL7 and CXCL10 orchestrate oxidative stress-induced neutrophilic lung inflammation. J Immunol. 2002;168:846–852. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.168.2.846. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Criqui GI, Solomon C, Welch BS, Ferrando RE, Boushey HA, Balmes JR. Effects of azithromycin on ozone-induced airway neutrophilia and cytokine release. Eur Respir J. 2000;15:856–862. doi: 10.1034/j.1399-3003.2000.15e08.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Jones SL, Eckert RE, Adler KB. MARCKS protein regulation of human neutrophil migration in vitro. FASEB J. 2008;22:666.6. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2008-0394OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Nairn AC, Aderem A. Calmodulin and protein kinase C crosstalk: the MARCKS protein is an actin filament and plasma membrane cross-linking protein regulated by protein kinase C phosphorylation and by calmodulin. Ciba Found Symp. 1992;164:145–154. doi: 10.1002/9780470514207.ch10. discussion 154–161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Park HS, Jung KS, Hwang SC, Nahm DH, Yim HE. Neutrophil infiltration and release of IL-8 in airway mucosa from subjects with grain dust-induced occupational asthma. Clin Exp Allergy. 1998;28:724–730. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2222.1998.00299.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Altstaedt J, Kirchner H, Rink L. Cytokine production of neutrophils is limited to interleukin-8. Immunology. 1996;89:563–568. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2567.1996.d01-784.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Barnes PJ, Shapiro SD, Pauwels RA. Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: molecular and cellular mechanisms. Eur Respir J. 2003;22:672–688. doi: 10.1183/09031936.03.00040703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kehrl HR, Peden DB, Ball B, Folinsbee LJ, Horstman D. Increased specific airway reactivity of persons with mild allergic asthma after 7.6 hours of exposure to 0.16 ppm ozone. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 1999;104:1198–1204. doi: 10.1016/s0091-6749(99)70013-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wagner JG, Jiang Q, Harkema JR, Illek B, Patel DD, Ames BN, Peden DB. Ozone enhancement of lower airway allergic inflammation is prevented by gamma-tocopherol. Free Radic Biol Med. 2007;43:1176–1188. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2007.07.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Wagner JG, Hotchkiss JA, Harkema JR. Enhancement of nasal inflammatory and epithelial responses after ozone and allergen coexposure in Brown Norway rats. Toxicol Sci. 2002;67:284–294. doi: 10.1093/toxsci/67.2.284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]