Abstract

Objective

Despite the tremendous disability and mortality caused by traumatic injuries worldwide, there is a relative dearth of information on the burden of injuries in developing countries. In an effort to document the surgical burden of disease in Sierra Leone, a nationwide survey was conducted utilizing the Surgeons OverSeas Assessment of Surgical Need (SOSAS) tool. Here, we report the injury data from this study with the aim to (1) provide an estimate of injury prevalence, (2) determine the mechanisms of injury, and (3) evaluate the degree of injury related deaths.

Methods

A population-based household survey was conducted in Sierra Leone in 2012. Participants were selected using a two-stage random sampling method, which generated a target population of 3750 participants across the 14 districts of Sierra Leone. Frequency distributions of mechanisms of injury based on age, sex, and urban versus rural residence were computed, and bivariate logistic regression models used to determine associations between sociodemographic factors and injury patterns.

Results

Data was analyzed from 1,843 households and 3,645 respondents, representing a response rate of 98.3%. Four hundred and fifty-two respondents (12.4%) reported at least one traumatic injury in the preceding year. Falls were the most common cause of non-fatal injuries, accounting for over 40% of injuries. The extremities were most commonly injured (55% of injuries) regardless of age or sex. Although motor vehicle related injuries were the 4th most common cause of injury overall, they were the leading cause of injury related deaths, accounting for almost 6% of fatal injuries.

Conclusion

This study provides baseline data on the burden of traumatic injuries in one of the world's poorest nations. In addition to injury prevention measures, immediate strategies to address current healthcare deficits are urgently needed in these resource poor areas.

This report is an Original Article with Level I evidence.

Keywords: Developing country, trauma, injury, population survey, Africa

Background

Injuries account a significant proportion of the global burden of disease, causing 9% of all deaths worldwide.1 More than 90% of injury related deaths occur in low and middle income countries,2 as demonstrated in studies in Nigeria,3 Ethiopia,4 and Kenya.5 Despite its overall significance, the burden and pattern of injuries in developing countries is not well known, and there have been a limited number of studies addressing this issue. Most of the available data is extrapolated from hospital-based studies, which inherently has limited generalizability since many patients with injuries will not go to a hospital.7, 8 Thus, the use of hospitalization data, particularly in in nations where surgical care is sparsely available, will exclude a significant proportion of patients with injuries and underestimate the incidence, prevalence and morbidity of traumatic injuries. 9

Another important caveat in addressing the overwhelming burden of traumatic injuries in low-income countries is that currently available trauma literature is mostly produced in high-income countries. Similar efforts to study injury in low-income countries, particularly in Sub-Saharan Africa, have been infrequent. As such, the global burden of disease due to trauma as well as injury epidemiology and prevention is vastly underrepresented in the trauma literature.11

In a community-based survey conducted in 1999, Mock et al found that agricultural injuries, falls, and transport related injuries were associated with a high burden of disability in urban and rural Ghana.12 More recently, population-based analyses of road traffic injuries in urban Tanzania13 and urban Ghana14 have further demonstrated that these injuries are a major source of disability in these settings. Together, these studies have helped to quantify the tremendous burden of morbidity and mortality associated with injuries in developing countries, and highlight the need for further data examining injuries on a larger scale.

Sierra Leone is a small West African country with a total population of 5.8 million people, of which 41.8% is pediatric (0-14 years), 54.5% adult (15-64 years) and 3.7% elderly (65 years and over). The male to female ratio within the age groups are approximately equivalent, except for a predominance of females in the elderly group (almost one third more females than males).15 As one of the world's poorest nations, Sierra Leone currently ranks 180 of the 187 nations on the United Nations Development Index. Health indicators for Sierra Leone reflect the limited availability of health care: life expectancy at birth is 48 years, and 175 per thousand children die before their 5th birthday.16

In an effort to document the surgical burden of disease in Sierra Leone, a nationwide survey was conducted utilizing the Surgeons OverSeas Assessment of Surgical Need (SOSAS) tool. This report details the results of this study pertaining to injury epidemiology in Sierra Leone, with the goal of providing baseline data that would be useful in the development of injury prevention efforts as well as devising immediate strategies to aid individuals currently suffering from injury-related illnesses.

Methods

Sampling

Statistics Sierra Leone provided baseline demographic information. The total population of Sierra Leone is distributed in 14 districts, which are further divided into chiefdoms followed by sections followed by enumerating areas (cluster). Each cluster has approximately 85 households (range 77-102). Participants were selected using a two-stage random cluster sampling, using a probability proportional to population. In the first stage of the sampling process, 75 clusters were randomly chosen nationwide, with stratification for district and urban and rural settings. In the second stage, 25 households within each cluster were randomly selected. This sampling methodology has been extensively utilized in developing countries, where accurate listings of households are unavailable.12, 17, 18

Study design

The study was conducted using of a cross-sectional population based survey, the Surgeons OverSeas Assessment of Surgical Need (SOSAS).19 Briefly, a questionnaire eliciting detailed socio-economic and demographic information on household members was administered to the head of each household. A list of all household members, including the head of household, was then created, and two persons from this list were assigned by a Random Calculator to be further interviewed. An adult caregiver provided responses for minors or individuals who were incapacitated. Information on deceased household members was sought from the head of the household. The two individuals selected to be interviewed were asked whether they had any injury occurring in the previous month, year, or over one year ago. If they answered affirmatively, a verbal questionnaire eliciting the mechanism of injury and the body region involved was further administered. All interviews were conducted verbally in the appropriate local language.

Data was gathered from January- February 2012. The survey was programmed with FileMaker Pro 11.0v2 (FileMaker Inc., Santa Clara, CA, USA) for direct computer entry on 3G iPad devices (Apple Inc., Cupertino, CA, USA) loaded with the survey in FileMaker Go 1.1 (FileMaker Inc., Santa Clara, CA, USA). Enumerators (nursing and medical students from who spoke the local languages) were trained for one week and sent out in teams. Field supervisors were available for queries and daily random data checks.

Statistical Analysis

Descriptive statistics were used to summarize sample characteristics and chi-squared tests used to assess differences between groups. Bivariate analysis was conducted to examine associations between having sustained a traumatic injury in the last year and independent variables (sex, age, residency, occupation, and education). A statistical significance (alpha) level of 0.05 was used throughout. SAS OnDemand Enterprise Guide 4.3 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC) was used to perform all statistical analysis.

Ethical clearance and informed consent

The study was a collaborative effort between Surgeons OverSeas (SOS), Sierra Leone Ministry of Health and Sanitation (MoHS), Connaught Hospital Department of Surgery, and Statistics Sierra Leone (SSL). Ethical approval was obtained from the Ethics and Scientific Review Committee of Sierra Leone, the Research Ethics Committee of the Royal Tropical Institute in Amsterdam, and the Institutional Review Board of Stanford University. Verbal consent was obtained from the EA leaders and written informed consent from the household leader as well as each randomly selected household member. For individuals under age 18 years, consent was obtained from the household representative or parent/guardian, and separately from the respondent. For children between 12-18 years old, the child was given the option of having a parent/ guardian present during the interview. For those under 12 years old, a parent/guardian either assisted the child with the interview or responded for the child.

Results

Demographic data and descriptive epidemiology

Data was collected and analyzed from 1,843 households and 3,645 respondents, giving a response rate of 98.3%. The remaining data was excluded based on inconsistences in the data from 25 households, missing information in 5 households, and consent refusal in 2 households. In 41 households, only one household member was interviewed, instead of the targeted 2 individuals per household. (See Groen et al, 2012 for additional details).20

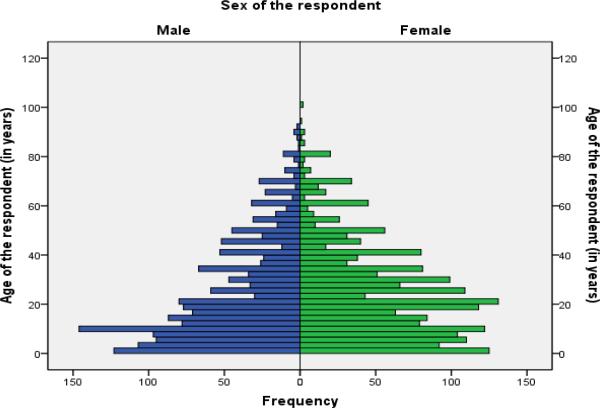

The demographic composition of the study population was similar to the most recent reports from the Sierra Leone Demographic Health Survey (2008 DHS), indicating a representative sample. The population structure shows a broad based pyramid when plotted by age and sex, characteristic of the population structure identified for developing countries (Figure 1). The mean age of respondents was 25 years (SD 19.7), with 36% (n=1313) under the age of 15 years, 57.9% (n=2109) between 15-64 years old, and 5.5% (201) older than 65 years. Age information was missing for 22 respondents (0.6%). There were more females than males, with 45.8% (n=1,669) male and 54.2% (n=1,976) female. Most respondents resided in rural areas (61.2 %, n=2231), compared to 38.8 % (n=1414) in urban regions.

Figure 1.

Demographic structure of the Sierra Leone SOSAS study population (2012).

Injury Prevalence

A total of 873 individuals (23.95% of respondents) reported having at least one lifetime traumatic injury, with 452 (12.4%) reporting at least one traumatic injury in the previous year. Further analysis of the timing of injury occurrence showed that 191 (5.24%) respondents suffered injuries in the previous month, 295 (8.09%) more than 1-month prior but within the past year, and 520 (14.27%) more than 1-year prior. Note that there are overlaps in respondents providing data on injuries at different time point since each person could report more than one injury. In total, 1316 injuries were reported.

As shown in Table 1, females were less likely to have experienced a traumatic injury in the previous year compared to males (OR= 0.69; CI 0.57-0.83). The odds of having a traumatic injury were similar for children and adults; however, elderly individuals were less likely to have experienced a traumatic injury in the previous year compared to children (OR = 0.51; CI = 0.31-0.83). Odds of having a traumatic injury in the previous year were not significantly different between groups when analyzing residency, occupation, or education level.

Table 1.

Bivariate analysis of factors associated with having at least one traumatic injury in the last year

| Proportion having at least one traumatic injury in the last year |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % (95% Confidence Interval for Population Percentage) | Crude odds ratio (95% Confidence Interval) | p-value | ||

| Gender | 0.0002 | ||||

| Male | 244 | 14.6 (12.6 - 16.6) | Reference | ||

| Female | 208 | 10.5 (8.6 - 12.5) | 0.69 (0.57, 0.83) | ||

| Age | 0.0468 | ||||

| 0-14 | 180 | 13.7 (11.5 - 15.9) | Reference | ||

| 15-64 | 256 | 12.1 (10.2 - 14.1) | 0.87 (0.72, 1.05) | ||

| >65 | 15 | 7.4 (4.0 - 10.9) | 0.51 (0.31, 0.83) | ||

| Missing | 1 | 4.5 (0.0 - 13.4) | 0.33 (0.44, 25.33) | ||

| Residency | 0.9717 | ||||

| Rural | 277 | 12.4 | Reference | ||

| Urban | 175 | 12.4 | 1.00 (0.81, 1.22) | ||

| Occupation | 0.2139 | ||||

| Unemployed | 219 | 12.3 (10.2, 14.4) | Reference | ||

| Homemaker | 15 | 13.9 (6.6, 21.1) | 1.15 (0.68, 1.93) | ||

| Domestic helper | 42 | 15.9 (11.9, 19.9) | 1.35 (0.96, 1.88) | ||

| Farmer | 108 | 12.8 (10.1, 15.4) | 1.04 (0.90, 1.36) | ||

| Self-employed | 46 | 10.2 (7.1, 13.4) | 0.81 (0.58, 1.14) | ||

| Government employee | 10 | 8.1 (2.8, 13.3) | 0.62 (0.31, 1.26) | ||

| Non-Government employee | 11 | 17.7 (10.7, 24.8) | 1.53 (1.00, 2.36) | ||

| Missing | 1 | 6.3 (0.0, 17.9) | 0.47 (0.06, 3.54) | ||

| Education | 0.7187 | ||||

| None | 221 | 11.7 (9.6, 13.8) | Reference | ||

| Primary | 103 | 12.7 (10.4, 15.1) | 1.10 (0.86, 1.41) | ||

| Secondary | 111 | 13.7 (10.7, 16.7) | 1.20 (0.91, 1.58) | ||

| Tertiary or Graduate | |||||

| Degree | 15 | 12.0 (6.6, 17.4) | 1.03 (0.62, 1.71) | ||

| Missing | 2 | 20.0 (0.9, 39.1) | 1.89 (0.54, 6.63) | ||

| TOTAL | 452 | 12.4 (10.6, 14.2) | |||

Mechanism of Injuries

Falls were the most common cause of injuries overall, accounting for over 40% of all injuries in both urban and rural areas (Table 2 and Table 3). Wounds due to lacerations/blunt trauma were the next most common, accounting for 27% of injuries in urban regions and 31% in rural areas. Burns were the third most common cause of injury and mostly involved hot liquids or objects. Rural residency was associated with increased odds of having a burn from a hot liquid of object (OR 0.68, CI 0.48- 0.98). Traffic related injuries, i.e. motor vehicle, motorcycle, bicycle or pedestrian crash, accounted for 13% of urban injuries and 9% of rural injuries. Bites and/or animal attacks and gunshot wounds were the least common causes of injury, accounting for 3% and 2% of all injuries, respectively.

Table 2.

Mechanism of Lifetime Injuries According to Urban versus Rural Residency

| Urban | Rural | Odds Ratio (Rural/Urban) | 95% Confidence Interval | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % of Urban Injuries | n | % of Rural Injuries | |||

| Fall | 198 | 41 | 365 | 44 | 1.17 | 0.94 - 1.47 |

| Stab / slash / cut / crush | 134 | 27 | 249 | 31 | 1.15 | 0.90 - 1.48 |

| Burn | ||||||

| Hot liquid / hot object | 64 | 13 | 77 | 9 | 0.68 | 0.48 - 0.98 |

| Open fire / explosion | 11 | 2 | 9 | 1 | 0.48 | 0.20 - 1.17 |

| Traffic related | ||||||

| Motorcycle crash | 26 | 6 | 36 | 4 | 0.81 | 0.49 - 1.37 |

| Car, truck, bus crash | 25 | 5 | 32 | 4 | 0.7522 | 0.44 - 1.29 |

| Pedestrian, bicycle crash | 11 | 2 | 9 | 1 | 0.48 | 0.20 - 1.17 |

| Bite or animal attack | 11 | 2 | 24 | 3 | 1.30 | 0.63 - 2.69 |

| Gunshot | 6 | 1 | 18 | 2 | 1.80 | 0.71 - 4.57 |

| Missing | 5 | 1 | 6 | 1 | 0.71 | 0.22 - 2.34 |

| TOTAL | 491 | 825 | ||||

Table 3.

Mechanism of Injury (Percentages and 95% Confidence Intervals) by Age Group and Sex in Urban and Rural Sierra Leone

| Age in years | Sex | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mechanism of Injury | 0-14 n=1313 | 15-64 n=2109 | ≥ 65 n=201 | male n=1669 | female n=1976 |

| Urban | |||||

| Fall | 11.4 (6.9, 15.8) | 12.0 (8.7, 15.4) | 9.1 (6.0, 12.2) | 15.5 (11.4, 19.5) | 8.8 (5.9, 11.8) |

| Stab / slash / cut / crush | 5.7 (3.6, 7.7) | 9.5 (5.9, 13.1) | 3.6 (0.0, 7.4) | 8.2 (6.0, 10.5) | 7.8 (4.3, 11.4) |

| Burn | 4.8 (3.0, 6.6) | 4.8 (2.8, 6.8) | 1.8 (0.0, 5.7) | 3.5 (1.7, 5.4) | 5.5 (3.4, 7.7) |

| Motorcycle crash | 0.4 (0.4, 0.5) | 2.5 (1.4, 3.6) | - | 2.9 (1.4, 4.4) | 0.8 (0.1, 1.4) |

| Car, truck, bus crash | 0.4 (0.0, 0.9) | 1.8 (0.7, 2.8) | 5.5 (0.0, 14.1) | 2.1 (0.8, 3.4) | 1.0 (0.4, 1.6) |

| Pedestrian, bicycle crash | 0.2 (0.0, 0.7) | 1.0 (0.0, 2.0) | - | 1.0 (0.1, 1.8) | 0.6 (0.0, 1.3) |

| Bite or animal attack | 0.9 (0.0, 1.8) | 0.8 (0.0, 1.6) | - | 1.3 (0.1, 2.5) | 0.4 (0.0, 0.8) |

| Gunshot | - | 0.7 (0.2, 1.1) | - | 0.6 (0.1, 1.2) | 0.3 (0.0, 0.6) |

| Total | 19.7 (13.4, 25.9) | 27.3 (19.3, 35.3) | 20.0 (10.8, 29.2) | 28.9 (21.7, 36.1) | 21.2 (14.0, 28.3) |

| Rural | |||||

| Fall | 10.5 (7.9, 13.2) | 13.4 (10.7, 16.1) | 24.0 (17.0, 30.9) | 15.3 (13.0, 17.5) | 10.7 (9.1, 12.4) |

| Stab / slash / cut / crush | 5.5 (3.7, 7.3) | 10.8 (8.6, 13.0) | 8.2 (3.8, 12.6) | 10.1 (7.8, 12.4) | 7.1 (5.3, 8,9) |

| Burn | 4.4 (3.0, 5.9) | 3.1 (1.9, 4.4) | 2.1 (0.0, 4.4) | 3.4 (2.1, 4.7) | 3.6 (2.5, 4.7) |

| Motorcycle crash | 0.6 (0.2, 1.0) | 1.9 (1.2, 2.7) | 1.4 (0.0, 3.3) | 2.1 (1.2, 3.0) | 0.7 (0.2, 1.1) |

| Car, truck, bus crash | - | 1.8 (1.1, 2.5) | 1.4 (0.0, 3.3) | 1.1 (0.4, 1.9) | 1.0 (0.4, 1.6) |

| Bite or animal attack | 1.3 (0.7, 1.9) | 0.7 (0.1, 1.1) | 2.1 (0.0, 4.4) | 0.9 (0.4, 1.3) | 1.1 (0.5, 1.7) |

| Gunshot | 0.1 (0.0, 0.4) | 0.9 (0.3, 1.5) | 2.1 (0.0, 4.2) | 1.3 (0.7, 2.0) | 0.1 (0.0, 0.3) |

| Pedestrian, bicycle crash | 0.1 (0.0, 0.4) | 0.5 (0.1, 0.9) | 1.4 (0.0, 3.4) | 0.7 (0.2, 1.2) | 0.2 (0.0, 0.4) |

| Total | 17.1 (14.6, 19.5) | 26.6 (22.9, 30.3) | 35.6 (28.7, 42.5) | 27.9 (25.3, 30.5) | 19.2 (16.3, 22.1) |

Analysis by age group in urban areas revealed that gunshot wounds were only reported in individuals age 15-64 (Table 3). Additionally, this group was also more likely to suffer injuries in motorcycle crashes compared to children and elderly (2.5% vs 0.4% in children and 0% in elderly respondents). In rural areas, falls were more likely in elderly individuals compared to younger age groups (24% versus 13.4% in adults and 10.5% in children). Additionally, adults were more likely to suffer injuries due to motorcycle crashes, motor vehicle crashes, and lacerations/blunt trauma compared to children (1.9% versus 0.6%, 1.8 versus 0% and 10.8% versus 5.5%, respectively). The overall percentage of individuals reporting injuries in rural areas increased with age, with 35.6% of elderly, 26.6% of adults and 17.1% of children reporting injuries.

When analyzed by sex (Table 3), there were no significant differences in the mechanisms of injury between male and female respondents in urban areas. In contrast, males in rural areas had a higher percentage of injuries due to falls (15.3% versus 10.7%), motor cycle crashes (2.1% versus 0.7%), and gunshot wounds (1.3% versus 0.1%) compared to females.

Body regions affected by injuries

The extremities were the most commonly injured across all age groups and in both males and females, accounting for 55% of all injuries (Table 4, Supplemental Figure 1). Injuries to the head and neck were the second most common, accounting for 16% of all injuries. Injury to the back accounted for 12%, followed by 7% on the chest and breast, 6% on the abdomen and 4% on the groin and buttocks.

Table 4.

Body Region Involved in Injury By Age and Sex

| Age in years |

Sex |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Body Region | 0-14 n=1313 | 15-64 n=2109 | ≥ 65 n=201 | p-value | Male n=1669 | Female n=1976 | p-value |

| Face/Head/Neck | 67 (28.3) | 133 (23.3) | 12 (19.0) | 0.3409 | 129 (27.2) | 83 (20.8) | < 0.0001 |

| Chest/Breast | 19 (8.0) | 65 (11.4) | 6 (9.5) | 0.0103 | 61 (12.9) | 29 (7.2) | < 0.0001 |

| Back | 27 (11.4) | 111 (19.4) | 16 (25.4) | < 0.0001 | 88 (18.6) | 66 (16.5) | 0.0024 |

| Abdomen | 33 (13.9) | 41 (7.2) | 3 (4.8) | 0.4424 | 35 (7.4) | 44 (11.0) | 0.7625 |

| Groin | 12 (5.1) | 37 (6.5) | 7 (11.1) | 0.0076 | 33 (7.0) | 23 (5.8) | 0.0040 |

| Extremities | 167 (70.5) | 396 (69.4) | 42 (66.7) | < 0.0001 | 320 (67.5) | 286 (71.7) | < 0.0001 |

| Total n of respondents with injuries (% of total n) | 237 (18.0) | 571 (27.0) | 63 (31.3) | 474 (28.4) | 399 (20.2) | ||

| Total n of injuries | 325 | 783 | 86 | 666 | 531 | ||

Values in brackets represent the percentage of respondents in that column reporting an injury, except where otherwise indicated.

Note: Age data was missing for 22 respondents, who were therefore excluded from the analysis by age.

Overall, the number of respondents with injuries increased with age, from 18% in children to 27% in adults and 31% in the elderly. Additionally, the percentage of reported injuries to the groin and back increased with age. Injuries to the groin were the least common site of injuries in children under 15 years (5.1%), compared to 6.5% in adults, and 11.1% in the elderly. Similarly, in children under 15 years, 11.4% of injuries were to the back, compared to 19.4% in adults, and 25.4% in elderly respondents.

Twenty eight percent of males reported an injury, compared to 20% of females. Males were more likely to have injuries to the head/ neck (27.2% versus 20.8%, p < 0.05), chest/breast (12.9% versus 7.2%, p< 0.05), and groin (7.0% versus 5.8%, p < 0.05) compared to females. Conversely, a significantly higher proportion of females reported injuries to the extremities compared to males (71.7% versus 67.5%, p<0.05).

Injury Related Deaths

Of the total 709 reported deaths, 41 deceased household members suffered an injury in the week prior to death (5.6%). Traffic injuries were the most common cause, accounting for 32% of fatal injuries. Falls accounted for 29%, bite or animal attacks for 19.5%, lacerations/crush injuries for 7.3%, and burns 7.3%. Five percent of injuries did not have a reported cause (Table 5).

Table 5.

Injuries in deceased household members during the week before death as reported by the head of the household.

| Cause of Injury | n | % of Total Fatal Injuries |

|---|---|---|

| Traffic Related | ||

| Car, truck, bus crash | 8 | 19.5 |

| Motorcycle crash | 5 | 12.2 |

| Fall | 12 | 29.3 |

| Bite or animal attack | 8 | 19.5 |

| Stab / slash / cut / crush | 3 | 7.3 |

| Burn | 3 | 7.3 |

| Unreported Cause of injury | 2 | 4.9 |

| Total | 41 | 100 |

Discussion

Traumatic injury epidemiology in low and middle-income countries remains an under-researched and relatively neglected subject area. This report highlights the tremendous burden of disease due to traumatic injury in one of the world's poorest nations, with a yearly non-fatal injury prevalence of 12.4% and fatal injury prevalence of 5.6% in the study sample. Extrapolating the sample prevalence to the entire population of over 5.8 million results in a total of 719,000 non-fatal traumatic injuries and 325,000 injury-related deaths in Sierra Leone in the past year.

Interestingly, there were no significant differences in the overall mechanisms of injuries in urban and rural areas. Falls were the single most common cause of non-fatal injuries, consistent with studies in Iran,21 Sri Lanka,22 and China.23 Falls from trees have been reported as a leading cause of injury in rural areas of developing countries such Nigeria25, 26 and Papua New Guinea,27 where the products of tall trees are important sources of food and income.24 In our study, elderly individuals in rural areas were more susceptible to fall injuries compared to other age groups. Falls in the elderly likely has different etiology and is associated with decreased daily physical activity.28, 29 Public health measures are needed to decrease the frequency and impact of falls, particularly in high-risk groups.

Lacerations/ crush injuries were the second most common cause of injury in this study, with adults having the highest percentage of these injuries. Studies in rural Ghana 12 and Tanzania30 have found lacerations to be the leading cause of injuries, with the majority of these injuries sustained during agricultural work. In Tanzania, most cuts and stabs were caused by instruments such as axes and machetes being utilized by rural residents engaging in agricultural activities without protective equipment.

Although motor vehicle related injuries were less common (4th most common cause of injury overall), they were the most common cause of injury-related deaths, accounting for over 30% of injuries in during the week prior to death. These findings are similar to those found by Mock et al in rural and urban Ghana, where transport related injuries were more severe than other types of injuries in terms of length of disability, mortality, and economic consequences.31 A possible explanation for the high mortality of traffic injuries in Sierra Leone may be the unavailability of appropriate safety equipment, as well as possible underutilization or incorrect use of available safety gear such as helmets and seatbelts. Additionally, there may be a delay in accessing care due to the poor road networks and the limited availability of rapid response vehicles.

Another interesting finding was that there was no difference in the mechanism of transport related injuries in urban and rural Sierra Leone; motorcycles and motor vehicles were about twice as likely to be the cause of injury compared to bicycle or pedestrian injuries. This is in contrast to the Ghanaian study, where traffic injuries in urban areas were mostly due to motor vehicle crashes and pedestrian accidents, whereas in rural areas most were due to bicycle crashes.31 The poor road network throughout Sierra Leone, both in urban and rural areas, may account for the relative similarity in traffic injury mechanisms.

Injuries due to gunshot wounds were uncommon in this series, and were only seen in the adult population. Studies in rural Ghana32 and Pakistan33 showed that assault was an infrequent mechanism of injury in these areas, and in the Ghanaian series none of the firearm injuries were due to assault. Further qualitative studies are needed to elucidate the circumstances surrounding firearm injuries.

In urban areas, there were no differences in the mechanisms of injuries when analyzed by sex. However, in rural areas a higher proportion of males suffered injuries due to falls, motorcycle crashes, and gunshot wounds, compared to females. This may be a reflection of the relative similarity of activities performed by males and females in urban areas, compared to more distinct roles of males and females in rural areas.

There have been a limited number of studies addressing the body regions most commonly injured in developing countries. However, this is an important consideration in order to determine the treatment strategies that may be needed. For instance, injuries to the extremities were most common regardless of age or sex, suggesting that orthopedic or reconstructive surgical strategies may be necessary for managing these injuries. Similarly, the high prevalence of head and neck injuries suggest that the services of otolaryngologists, ophthalmologists, dentists, plastic and reconstructive surgeons, or other individuals trained in these skill sets are likely needed to help address the current cases.

It is unclear why the number of reported injuries to the groin and back increased with age. One possible explanation may be that given the high number of falls, the reported groin injuries may be related to hip fractures. Another possibility may be that inguinal hernias were misclassified as traumatic injuries, given that the study was based on the respondent's perspectives. Respondents may also consider back pain related to field labor as a form of traumatic injury. Qualitative research may be useful for further clarification.

Limitations

There are a few limitations to this study that must be addressed. Firstly, the study relied on self-reporting by the respondents. It is likely that there was under-reporting and hence underestimation of the prevalence of injuries associated with a social stigma, such as domestic violence, female genital mutation, or suicide. Additionally, there may also be under-reporting due to recall bias, which was not evaluated in this study. In the absence of a physical examination, we were unable to explore the extent of probable under reporting. Even so, we believe that the estimates of this study are less prone to underestimation compared to hospital-based studies.7, 8 Secondly, the survey was primarily designed to capture the prevalence of surgical treatable conditions; as such, detailed information on the circumstances of injuries such as intentional versus unintentional or whether safety precautions were in place at the time of the injury was not elicited. Thirdly, although efforts were made to generate a representative sample of Sierra Leone's population, the higher female proportion in our sample likely confirms that the household survey by nature excludes individuals who are away from the home, such as those who are institutionalized, military personnel or miners.

Conclusions

Utilizing the results of a nationwide survey, we have provided population-based estimates of the prevalence of disease due to traumatic injury in Sierra Leone, as well as insights into the mechanism of these injuries. It is hoped that this evidence will provide the stimulus for international aid organizations and local government agencies to implement preventative measures and immediate strategies to address current injury related healthcare needs in Sierra Leone and other developing countries. For instance, it may be necessary to implement/ enforce transportation safety measures, improve medical rapid response systems, train community health officers in rural areas to effectively deal with injuries, and provide improved surgical care throughout the region.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Funding: Funding for logistical support was provided by Surgeons OverSeas (SOS) with a donation from the Thompson Family Foundation. The Sierra Leone Ministry of Health & Sanitation, College of Medicine and Allied Health Sciences and Connaught Hospital assisted with local transportation and administrative support. None of the authors is funded for their contributions to the manuscript.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest: None.

Disclosure: This article is part of a series of articles on the surgical need in Sierra Leone.

Contributor Information

Kerry-Ann Stewart, School of Medicine, Stanford University, Stanford, California, USA.

Reinou S. Groen, Surgeons OverSeas (SOS), New York, NY, USA Royal Tropical Institute, Amsterdam, the Netherlands.

Thaim B. Kamara, Department of Surgery, Connaught Hospital, Freetown, Sierra Leone.

Mina Farahzard, Institute for Health and Society, Medical College of Wisconsin, Milwaukee WI.

Mohamed Samai, College of Medicine and Allied Health Science (COMAHS), Freetown, Sierra Leone.

Sahr E. Yambasu, Statistics Sierra Leone (SSL), Freetown, Sierra Leone.

Laura D. Cassidy, Assistant professor Institute for Health and Society and director of the epidemiology program, Medical College of Wisconsin, Milwaukee WI

Adam L. Kushner, Surgeons OverSeas (SOS), New York, NY, USA Department of Surgery, Columbia University, New York, New York, USA.

Sherry M. Wren, Department of Surgery, Stanford University, Stanford, California, USA.

References

- 1.Peden MMKSG. The injury chart book: a graphical overview of the global burden of injuries. World Health Organization; Geneva: 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Peden M. The injury chart book: a graphical overview of the global burden of injuries. World Health Organization; Geneva: 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ezenwa AO. Trends and characteristics of road traffic accidents in Nigeria. J R Soc Health. 1986;106(1):27–9. doi: 10.1177/146642408610600111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gedlu E. Accidental injuries among children in north-west Ethiopia. East Afr Med J. 1994;71(12):807–10. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Omondi O, van Ginneken JK, Voorhoeve AM. Mortality by cause of death in a rural area of Machakos District, Kenya in 1975-78. J Biosoc Sci. 1990. 22(1):63–75. doi: 10.1017/s0021932000018381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Manciaux M, Romer CJ. Accidents in children, adolescents and young adults: a major public health problem. World Health Stat Q. 1986;39(3):227–31. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mock CN, nii-Amon-Kotei D, Maier RV. Low utilization of formal medical services by injured persons in a developing nation: health service data underestimate the importance of trauma. J Trauma. 1997;42(3):504–11. doi: 10.1097/00005373-199703000-00019. discussion 11-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hang HM, Byass P. Difficulties in getting treatment for injuries in rural Vietnam. Public Health. 2009;123(1):58–65. doi: 10.1016/j.puhe.2008.07.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kingham TP, Kamara TB, Cherian MN, Gosselin RA, Simkins M, Meissner C, et al. Quantifying surgical capacity in Sierra Leone: a guide for improving surgical care. Arch Surg. 2009;144(2):122–7. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.2008.540. discussion 8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lyons RA, Brophy S, Pockett R, John G. Purpose, development and use of injury indicators. Int J Inj Contr Saf Promot. 2005;12(4):207–11. doi: 10.1080/17457300500172776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Noordin S, Wright JG, Howard AW. Global relevance of literature on trauma. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2008;466(10):2422–7. doi: 10.1007/s11999-008-0397-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mock CN, Abantanga F, Cummings P, Koepsell TD. Incidence and outcome of injury in Ghana: a community-based survey. Bull World Health Organ. 1999;77(12):955–64. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zimmerman K, Mzige AA, Kibatala PL, Museru LM, Guerrero A. Road traffic injury incidence and crash characteristics in Dar es Salaam: a population based study. Accid Anal Prev. 2012;45:204–10. doi: 10.1016/j.aap.2011.06.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Guerrero A, Amegashie J, Obiri-Yeboah M, Appiah N, Zakariah A. Paediatric road traffic injuries in urban Ghana: a population-based study. Inj Prev. 2011;17(5):309–12. doi: 10.1136/ip.2010.028878. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.The World Factbook . Central Intelligence Agency; Washington, DC: 2009. 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 16.World Health Organization statistical information system. 2008 [Google Scholar]

- 17.Henderson RH, Sundaresan T. Cluster sampling to assess immunization coverage: a review of experience with a simplified sampling method. Bull World Health Organ. 1982;60(2):253–60. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bennett S, Woods T, Liyanage WM, Smith DL. A simplified general method for cluster-sample surveys of health in developing countries. World Health Stat Q. 1991;44(3):98–106. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Groen RS, Samai M, Petroze RT, Kamara TB, Yambasu SE, Calland JF, et al. Pilot Testing of a Population-based Surgical Survey Tool in Sierra Leone. World J Surg. doi: 10.1007/s00268-012-1448-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Groen RS, Samai M, Stewart KA, Cassidy LD, Kamara TB, Yambasu SE, et al. Uncovering the high prevalence of untreated surgical conditions: Results of a cross-sectional countrywide household survey of surgical need in Sierra Leone. The Lancet. 2012 doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)61081-2. In press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Saadat S, Mafi M, Sharif-Alhoseini M. Population based estimates of non-fatal injuries in the capital of Iran. BMC Public Health. 11:608. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-11-608. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Navaratne KV, Fonseka P, Rajapakshe L, Somatunga L, Ameratunga S, Ivers R, et al. Population-based estimates of injuries in Sri Lanka. Inj Prev. 2009;15(3):170–5. doi: 10.1136/ip.2008.019943. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ma J, Guo X, Xu A, Zhang J, Jia C. Epidemiological analysis of injury in Shandong Province, China. BMC Public Health. 2008;8:122. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-8-122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Smith GS, Barss P. Unintentional injuries in developing countries: the epidemiology of a neglected problem. Epidemiologic reviews. 1991;13:228–66. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.epirev.a036070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ebong WW. Falls from trees. Tropical and geographical medicine. 1978;30(1):63–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Okonkwo CA. Spinal cord injuries in Enugu, Nigeria--preventable accidents. Paraplegia. 1988;26(1):12–8. doi: 10.1038/sc.1988.5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Barss P, Dakulala P, Doolan M. Falls from trees and tree associated injuries in rural Melanesians. Br Med J (Clin Res Ed) 1984;289(6460):1717–20. doi: 10.1136/bmj.289.6460.1717. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lau EM, Cooper C, Wickham C, Donnan S, Barker DJ. Hip fracture in Hong Kong and Britain. Int J Epidemiol. 1990;19(4):1119–21. doi: 10.1093/ije/19.4.1119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wickham C, Cooper C, Margetts BM, Barker DJ. Muscle strength, activity, housing and the risk of falls in elderly people. Age and ageing. 1989;18(1):47–51. doi: 10.1093/ageing/18.1.47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Moshiro C, Heuch I, Astrom AN, Setel P, Hemed Y, Kvale G. Injury morbidity in an urban and a rural area in Tanzania: an epidemiological survey. BMC Public Health. 2005;5:11. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-5-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mock CN, Forjuoh SN, Rivara FP. Epidemiology of transport-related injuries in Ghana. Accid Anal Prev. 1999;31(4):359–70. doi: 10.1016/s0001-4575(98)00064-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mock CN, Adzotor E, Denno D, Conklin E, Rivara F. Admissions for injury at a rural hospital in Ghana: implications for prevention in the developing world. Am J Public Health. 1995;85(7):927–31. doi: 10.2105/ajph.85.7.927. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ahmed M, Shah M, Luby S, Drago-Johnson P, Wali S. Survey of surgical emergencies in a rural population in the Northern Areas of Pakistan. Trop Med Int Health. 1999;4(12):846–57. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-3156.1999.00490.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mock C, Acheampong F, Adjei S, Koepsell T. The effect of recall on estimation of incidence rates for injury in Ghana. Int J Epidemiol. 1999;28(4):750–5. doi: 10.1093/ije/28.4.750. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.