Abstract

INTRODUCTION

Occasionally, lymph node metastases represent the only component at the time of recurrence of ovarian cancer. Here we report the case of a 78-year-old Japanese female who underwent successful surgery for recurrent ovarian cancer with multiple lymph node metastases.

PRESENTATION OF CASE

The patient was referred to our institution with recurrent disease accompanied by chemoresistant multiple retroperitoneal lymph node metastases five years after the initial therapy for stage IIIc serous adenocarcinoma of the ovary. Positron emission tomography/computed tomography (PET/CT) revealed the involvement of two para-aortic nodes and two pelvic nodes, with no other positive site. The patient underwent systematic para-aortic and pelvic lymphadenectomy, and the metastatic nodes were completely resected. Histopathological examination revealed metastatic high-grade adenocarcinoma in four of 63 dissected lymph node specimens. The patient has been in clinical remission for over four years without any further additional therapies.

DISCUSSION

In our case, the metastatic nodes predicted by PET/CT completely corresponded to the actual metastatic nodes; however, PET/CT often fails to identify microscopic disease in pathological positive nodes. We cannot reliably predict whether lymph node metastasis will persist in the limited range. Therefore, systematic lymphadenectomy with therapeutic intent should be performed, although it does not always mean that we remove all cancer cells.

CONCLUSION

The findings from this case suggest that, even if used as secondary cytoreductive surgery in the context of a recurrent disease, systematic aortic and pelvic node dissection might sometimes contribute to the control if not cure of ovarian cancer.

Keywords: Ovarian cancer, Secondary cytoreductive surgery, Pelvic lymphadenectomy, Paraaortic lymphadenectomy

1. Introduction

The majority of patients with ovarian cancer are diagnosed at advanced stages, and this form of cancer is considered to be the most lethal gynecological cancer. At least 50% patients ultimately develop recurrent disease and succumb, despite achieving clinical remission after completion of initial treatment.1 The most common site for recurrence of ovarian cancer is the intraperitoneal cavity. Occasionally, however, lymph node metastases represent the predominant or only component at the time of recurrence. The rationale for extensive aortic and pelvic node dissection is based on the observation that the rate of lymph node metastases at surgery after chemotherapy is similar to or only modestly lower than that at initial surgery, indicating that nodal disease is less curable by chemotherapy compared with disease at other sites.2,3 Here we report the case of a 78-year-old Japanese who underwent successful surgery for recurrent ovarian cancer with multiple lymph node metastases and has been alive with no evidence of disease for more than four years thereafter.

2. Presentation of case

A 73-year-old Japanese female was diagnosed with advanced ovarian cancer at a cancer center in Tokyo. After neoadjuvant chemotherapy with one cycle of paclitaxel plus carboplatin and one cycle of docetaxel (converted from paclitaxel because of hypersensitivity to paclitaxel) plus carboplatin, she had undergone an interval cytoreductive surgery consisting of hysterectomy, bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy, partial omentectomy, and peritoneal stripping. The surgery was considered optimal according to the intraoperative findings (i.e., the size of intraperitoneal residual tumors was less than 1 cm in diameter), although lymph nodes were not dissected. Histopathologically, the tumor was a high-grade serous adenocarcinoma (Stage IIIc, pT3cNxM0). Following six cycles of adjuvant chemotherapy of docetaxel plus carboplatin, she achieved a complete clinical response. Thereafter, she was administered oral etoposide and carboplatin sequentially for 11 months as maintenance chemotherapy.

Twenty-seven months after the initial treatment was started (22 months after the initial treatment was completed), she experienced the first relapse, which was diagnosed by examining elevated serum CA125 levels and computer tomography (CT) images of enlarged para-aortic nodes (PANs). She received one cycle of docetaxel plus carboplatin and three cycles of second-line chemotherapy with gemcitabine plus carboplatin (converted from the prior regimen because of adverse effects from docetaxel). Because she had experienced a hypersensitivity reaction with carboplatin in the third cycle of the regimen and had achieved clinical remission, she was followed without any further treatment.

The second relapse was noted 11 months after the first, with the same relapse site diagnosed by CT images. She received nine cycles of third-line chemotherapy with irinotecan plus cisplatin for 11 months. Although the tumors initially decreased in size, they subsequently stopped shrinking. Thereafter, although she was administered oral etoposide for four months, PAN and pelvic lymph node size increased and serum CA125 levels elevated gradually. The patient was persuaded that the best supportive care was the only remaining option. However she wished to explore the possibility of any further treatment. Sixty-two months after the first treatment initiation, she was referred to our institution with a seven months therapy-free interval.

Her Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) performance status was 1 without any complaints, although she suffered from mild hypertension and took medication for the same. Her laboratory data were within normal limits, except that serum CA125 levels increased to 104.5 U/ml.

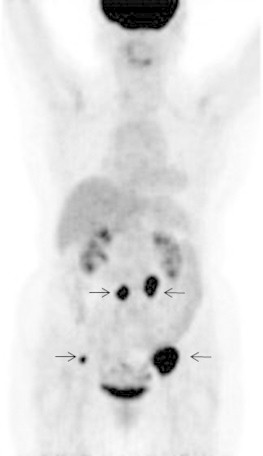

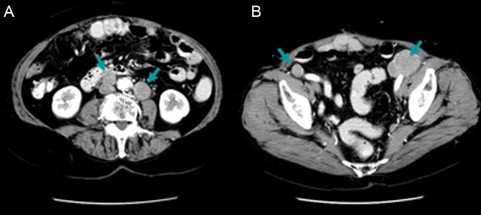

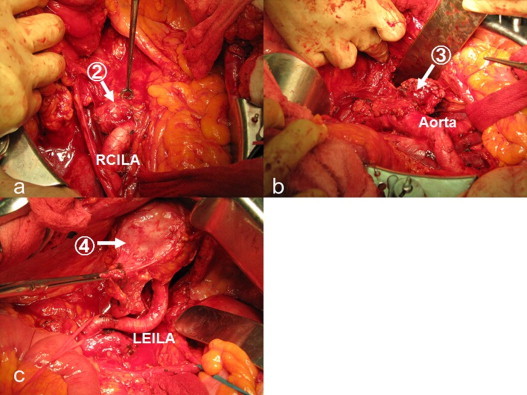

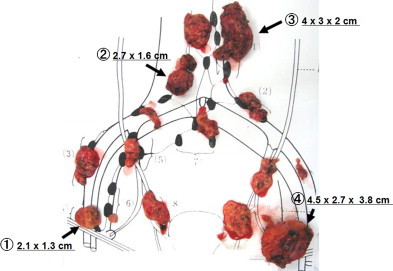

Positron emission tomography/computed tomography (PET/CT) revealed the involvement of two PANs (31 mm × 25 mm and 24 mm × 18 mm, respectively) and two pelvic nodes (38 mm × 45 mm and 13 mm × 16 mm, respectively), and there was no other positive site (Fig. 1). Contrast-enhanced CT clearly identified these enlarged nodes, which we considered to be resectable (Fig. 2). After providing written informed consent, she underwent systematic PAN and pelvic lymphadenectomy. The retroperitoneal metastatic nodes were completely resected in the absence of significant adhesion to the vessels during surgery (surgical duration: 324 min, blood loss: 930 g [Fig. 3]). Histopathologically, we confirmed metastatic high-grade adenocarcinomas in four of 63 dissected lymph node specimens, which were identical to the nodes detected on PET/CT and CT (Fig. 4). Macroscopically, there was no intraperitoneal disease. Peritoneal cytology was negative. Despite thrombo-prophylaxis with intermittent pneumatic compression of the legs and subcutaneous crude heparin administration was employed, on postoperative day two, she experienced mild pulmonary embolism, which ameliorated, without any adverse events, after anticoagulation therapy with intravenous heparin and, subsequently, oral warfarin. She discharged on postoperative day 25. We refrained from performing any adjuvant therapy after SDS, because the patient preferred a follow-up regimen with no further intervention. She is being followed-up at our outpatient clinic and has been in good health with no evidence of disease for over 50 months after surgery.

Fig. 1.

Positron emission tomography shows four positive lymph nodes, but no other positive sites.

Fig. 2.

Enhanced computed tomography (CT) images clearly shows enlarged nodes. (A) Precaval and lateroaortic nodes. (B) Bilateral suprainguinal nodes.

Fig. 3.

Images of lymph node dissection (2) corresponds to the precaval node, (3) corresponds to the lateroaortic node, and (4) corresponds to the left suprainguinal node. (1) The right suprainguinal node is not indicated here. Abbreviations: RCILA, right common iliac artery; LEILA, left external iliac artery.

Fig. 4.

Macroscopic appearance of dissected lymph nodes. Microscopically, four (1–4) out of 63 dissected lymph nodes were positive for metastatic adenocarcinoma.

3. Discussion

Although primary cytoreductive surgery is well accepted as the cornerstone of initial management, the role of cytoreductive surgery in the setting of recurrent disease remains controversial. Several retrospective studies have demonstrated a benefit of secondary cytoreductive surgery (SCS) and identified the prognostic factors for survival in these patients, including performance status, disease-free interval, number of recurrent tumors, maximum size of tumors, presence of liver metastases, and presence of carcinomatosis.4–6

According to these prognostic factors, selection criteria or guidelines for SCS have been proposed. For instance, Chi et al. proposed a recommendation for SCS on the basis of disease-free interval, number of recurrence sites, and evidence of carcinomatosis.6 Our patient fulfilled their criteria: no carcinomatosis despite the presence of multiple recurrence sites, and a disease-free interval of more than 12 months. Meanwhile, Bristow et al. reviewed 40 cohort studies of patients undergoing surgical intervention for recurrent ovarian cancer (2019 patients).7 They concluded that only that proportion of patients undergoing complete cytoreduction is independently associated with overall post-recurrence survival time. Panici et al. evaluated the role of systematic lymphadenectomy in ovarian cancer patients with recurrent bulky lymph node disease.8 They concluded that these patients could benefit from systematic lymphadenectomy in terms of survival, although all 29 patients had received postoperative adjuvant treatment. To achieve complete cytoreduction of tumor, systematic lymphadenectomy with therapeutic intent (not a diagnostic one) should be performed as described in the textbook by Morrow and Curtin.9 Even so, removing all the lymph nodes that we can reach or find does not always mean that we remove all cancer cells. We occasionally experience recurrent ovarian cancer patients with lymph node metastases spread to multiple sites. In our patient, the metastatic nodes predicted by PET/CT completely corresponded to the actual metastatic nodes. In general, when conventional CT findings are negative or equivocal, PET/CT demonstrates high sensitivity and a positive predictive value in identifying recurrent ovarian cancer in retroperitoneal lymph nodes. Bristow et al., however, reported that PET/CT failed to identify microscopic disease in nearly 60% of pathological positive nodes.10 Thus, we cannot reliably predict whether lymph node metastasis will persist in the limited range. One hypothesis is that a relatively slow increase in the serum CA 125 level during a treatment-free period, as in our case, may be one sign of possible complete cytoreduction of a tumor, because it may suggest that the tumor is in a dormant state. Further cohort studies with large sample size would be warranted to address these issues.

Even with the above-mentioned limitation, we have several criteria that need to be fulfilled before considering retroperitoneal lymphadenectomy as SCS for patients with recurrent ovarian cancer. First, lymph nodes metastasis should be at least assessed with PET/CT and contrast-enhanced CT to confine within the resectable area, without any other recurrent lesions. Second, the lesions should be surgery- and irradiation-naive, regardless of the number of metastases. The disease-free interval and the ECOG performance status of patients should also be considered. Although not so severe, our patient experienced pulmonary embolism postoperatively. To avoid severe complications, preoperative assessment of risks for them and perioperative management should be taken meticulously.

4. Conclusion

We experienced the case of a Japanese female who underwent successful surgery for recurrent ovarian cancer with multiple lymph node metastases. Retrospectively, there may have been no recurrence in the patient if systematic lymphadenectomy had been performed during the initial surgery. This is just a case report and we cannot make general conclusions. However, our findings suggest that systematic aortic and pelvic node dissection might sometimes contribute to the control if not cure of ovarian cancer, even if used as SCS in the context of a recurrent disease. Physicians should not abandon any possibility to control a cancer as long as the patient chooses to do so.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest in undertaking this study.

Funding

None.

Ethical approval

Written informed consent was obtained from the patient for publication of this case report and accompanying images. A copy of the written consent is available for review by the Editor-in-Chief of International Journal of Surgery Case Reports.

Author contributions

Hiroaki Nagano was involved in the medical management, surgery, data collections, data analysis, and writing. Mitsue Muraoka did the medical management and surgery. Koichiro Takagi did the medical management, surgery, and writing.

Key learning points.

-

•

Even if used in the context of a recurrent disease, systematic lymphadenectomy with therapeutic intent might sometimes contribute to the control if not cure of ovarian cancer.

References

- 1.Fleming G.F., Ronnett B.M., Seidmann J., Zaino R.J., Rubin S.C. Epithelial ovarian cancer. In: Barakat R.R., Markman M., Randall M.E., editors. Principles and practice of gynecologic oncology. 5th ed. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; Philadelphia: 2009. pp. 763–835. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Burghardt E., Girardi F., Lahousen M., Tamussino K., Stettner H. Patterns of pelvic and paraaortic lymph node involvement in ovarian cancer. Gynecol Oncol. 1991;40:103–106. doi: 10.1016/0090-8258(91)90099-q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Scarabelli C., Gallo A., Zarrelli Z., Visentin C., Campaqnutta E. Systemic pelvic and para-aortic lymphadenectomy during cytoreductive surgery in advanced ovarian cancer: potential benefit on survival. Gynecol Oncol. 1995;56:328–337. doi: 10.1006/gyno.1995.1059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Onda T., Yoshikawa H., Yasugi T., Yamada M., Matsumoto K., Taketani Y. Secondary cytoreductive surgery for recurrent epithelial ovarian carcinoma: proposal for patients selection. Br J Cancer. 2005;92:1026–1032. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6602466. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Harter P., du Bois A., Hahmann M. Surgery in recurrent ovarian cancer: the arbeitsgemeinschaft gynaekologische onkologie (AGO) DESKTOP OVAR trial. Ann Surg Oncol. 2006;13:1702–1710. doi: 10.1245/s10434-006-9058-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chi D.S., McCaughty K., Diaz J.P. Guidelines and selection criteria for secondary cytoreductive surgery in patients with recurrent, platinum-sensitive epithelial ovarian carcinoma. Cancer. 2006;106:1933–1939. doi: 10.1002/cncr.21845. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bristow R.E., Puri I., Chi D.S. Cytoreductive surgery for recurrent ovarian cancer: a meta-analysis. Gynecol Oncol. 2009;112:265–274. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2008.08.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Panici P.B., Perniola G., Angioli R. Bulky lymph node resection in patients with recurrent epithelial ovarian cancer: impact of surgery. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2007;17:1245–1251. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1438.2007.00929.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Morrow C.P., Curtin J.P. Churchill Livingstone; New York: 1996. Gynecologic cancer surgery. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bristow R.E., Giuntoli R.L., II, Pannu H.K., Schulick R.D., Fishman E.K., Wahl R.L. Combined PET/CT for detecting recurrent ovarian cancer limited to retroperitoneal lymph nodes. Gynecol Oncol. 2005;99:294–300. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2005.06.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]