Abstract

INTRODUCTION

The Holt–Oram syndrome is a rare congenital disorder involving the skeletal and cardiovascular systems. It is characterized by upper limb deformities and cardiac malformations, atrial septal defects in particular.

PRESENTATION OF CASE

Four consecutive patients 1–15 years old with the Holt–Oram syndrome presented over a 10 year span for surgical treatment of their cardiac maladies. The spectrum of the heart defects and skeletal deformities encountered in these patients are described and discussed.

DISCUSSION

The Holt–Oram syndrome is an autosomal dominant condition; however absence of the morphological features of the trait in close family members is not rare. Although patients are known to predominately present with atrial septal defects, other cardiovascular anomalies, including rhythm abnormalities, are not uncommon. Skeletal disorders vary as well.

CONCLUSION

Cardiovascular disorders, skeletal malformations and familial expression of the Holt–Oram syndrome, vary widely.

Keywords: Heart-limb, Holt–Oram, Syndrome, Congenital, Heart disease, Skeletal disorders

1. Introduction

The Holt Oram syndrome is characterized by congenital cardiovascular malformations and skeletal abnormalities of the upper limbs, hence, the terms “heart-hand syndrome” and “heart upper-limb syndrome”. Arm deformity covers a wide range of anomalies extending from minor abnormalities, through to serious, even handicapping, malformations. The most common cardiac manifestation is atrial septal defect (ASD); however, other structural abnormalities and also rhythm disorders have been described.1 We herein present our experience in 4 consecutive patients over a 10 year period with the Holt Oram syndrome (Table 1).

Table 1.

Patients’ characteristics and pathology.

| Case 1 | Case 2 | Case 3 | Case 4 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Male | Female | Male | Female |

| Age (years) | 15 | 4 | 1 | 2 |

| Family trait | No | No | No | Yes |

| Skeletal disorders | Kyphosis, absent fingers of the (R) hand | Bilateral upper limb dysplasia, short ring fingers | Kyphosis, scoliosis, hypoplastic clavicles, pectus excavatum, thumb and index syndactyly (L), short and forward displacement of thumb (R) | Thumb and index syndactyly (L), short and forward displacement of thumb (R) |

| CHD | TOF/PA | ASD | TOF/ASD | VSD, mitral cleft |

| Psychomotor disorders | No | Yes – mental retardation, epilepsy | No | No |

| ECG | SR, RAE, LAE, right axis, RVH, T abnormality | Sinus atrial tachycardia, incomplete RBBB, RVH | SR, PVC, right axis | SR |

| Operation | Aorta to pulmonary artery shunt | ASD patch closure | TOF repair/ASD patch closure | Pulmonary artery banding |

| ICU/hospital stay (days) | 1/8 | 3/8 | 6/9 | 5/9 |

CHD, congenital heart disease; ECG, electrocardiogram; TOF, tetralogy of Fallot; PA, pulmonary atresia; ASD, atrial septal defect; VSD, ventricular septal defect; ICU, intensive care unit; SR, sinus rhythm; PVC, premature ventricular contractions; RBBB, right bundle branch block; RAE, right atrial enlargement; LAE, left atrial enlargement, RVH, right ventricular hypertrophy; (R), right; (L), left.

2. Cases

2.1. Case 1

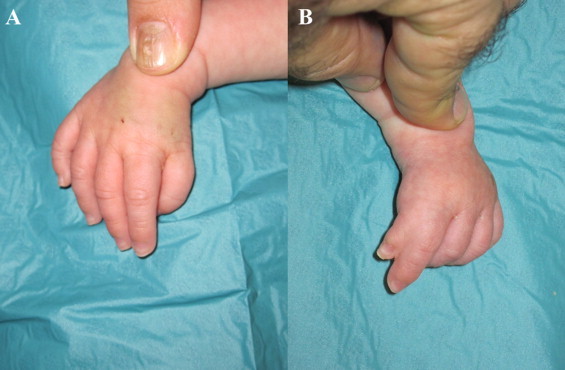

A 15-year-old boy with tetralogy of Fallot presented followed by a history of two previous aorto-pulmonary shunts and a stroke. Physical examination revealed prominent kyphosis, and absent index, ring and little fingers of the right hand (Fig. 1). Electrocardiography (ECG) showed sinus rhythm (SR), biatrial enlargement, right axis, right ventricular hypertrophy (RVH) and T wave abnormalities. Echocardiography revealed a large ventricular septal defect (VSD), pulmonary atresia and hypoplastic pulmonary arteries. The patient underwent a successful construction of a new central shunt, made an uneventful recovery and was discharged home in good condition.

Fig. 1.

Case #1. Right thumb and middle finger.

2.2. Case 2

An asymptomatic 4-year-old girl presented with an ASD. On examination she was found to have short both upper limbs and ring fingers. She was also diagnosed with mental retardation, psychomotor disorders and epilepsy in the context of trisomy 13. ECG showed sinus atrial tachycardia, incomplete right bundle branch block (RBBB) and RVH. Echocardiography revealed a large secundum ASD. The patient underwent surgical closure of the defect and was discharged from hospital in excellent clinical condition.

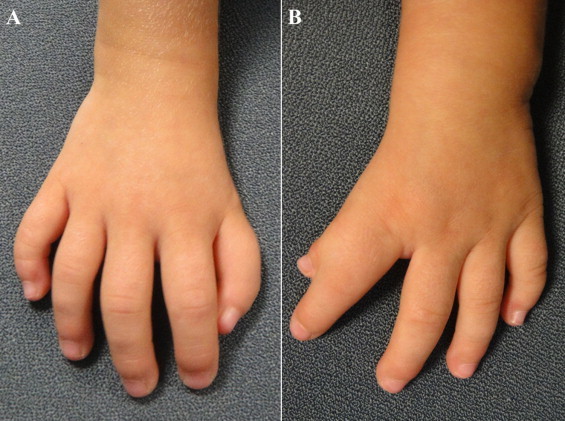

2.3. Case 3

A 1-year-old boy presented with tetralogy of Fallot. On examination, kyphosis, scoliosis, hypoplastic clavicles, pectus excavatum, syndactyly of the left thumb and index finger and forward displacement of the right thumb were noted (Fig. 2). The ECG showed SR, ventricular premature complexes and abnormal right axis deviation. Echocardiography revealed a large VSD, aortic overriding, right ventricular outflow tract obstruction, RVH and also a secundum ASD. The patient underwent standard surgical correction, made a good overall recovery and was discharged home in good clinical condition.

Fig. 2.

Case #3. (A) Right thumb forward displaced. (B) Left thumb-index finger syndactyly.

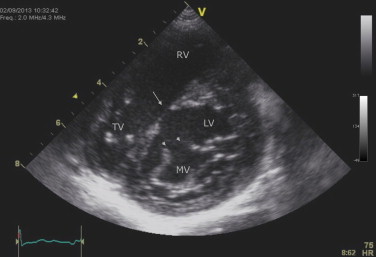

2.4. Case 4

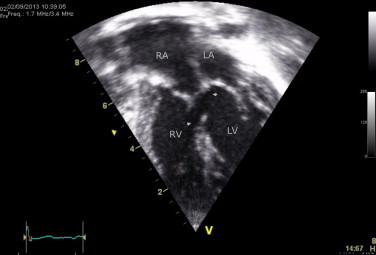

A 2-year-old girl presented with a canal type VSD, concomitant mitral cleft and a history of a pulmonary artery banding at the age of 1 month. Physical examination revealed syndactyly of the left thumb and index finger and forward displacement of the right thumb (Fig. 3). Her father exhibited similar skeletal abnormalities. ECG showed SR. Echocardiography revealed a large perimembranous VSD and a mitral cleft without a primum septal defect (Figs. 4 and 5). Currently, she is on the list for total repair.

Fig. 3.

Case #4. (A) Right thumb forward displaced. (B) Left thumb-index finger syndactyly.

Fig. 4.

Case #4. TTE: short-axis parasternal view – mitral valve (anterior leaflet) cleft (short arrows) and VSD (long arrow).

Fig. 5.

Case #4. TTE: four-chamber view – primum-type VSD (arrows).

3. Discussion

The Holt–Oram syndrome is an autosomal dominant condition first described in 1960 by Mary Holt and Samuel Oram and was named after them a year later by Victor McKusick, when describing a similar case.2,3 Multiple transcription factors regulate specific programs of gene expression in heart development.4 Of these, TBX5, member of a family characterized by a highly conserved DNA binding motif (T-box) participates in the specification of left/right ventricles and ventricular septum position during cardiogenesis.5,6 The Holt–Oram syndrome is caused by the mutation of a gene residing on the long arm of the chromosome 12q24.5 It is argued, however, that heart-limb syndromes are expressed by mutation in different genes suggesting a genetically heterogeneous disease with just one locus mapping on this chromosome.7 TBX5, nonetheless, directly or indirectly, alters the transcription of different genes in heart and limb.1,5,8,9

Inward directed thumb as in the original description by Holt and Oram was found in 3 of our patients.2 However, a large number of different skeletal abnormalities have been reported. In particular, distally displaced, triphalangeal thumbs, hypoplastic thenar eminences, hypoplastic, absent or extra fingers, anomalies of the carpus, radial aplasia, phocomelia, hypoplasia of the clavicles and shoulders and pectus excavatum have been described. Upper extremity deformity is in the preaxial radial ray distribution, usually bilateral, yet may be asymmetrical in severity, the left side usually being the worst.2,8,10–13

The most frequent cardiac abnormalities are ASDs, followed by VSDs.1,12–16 Nonetheless 17.5% of patients have severe cardiac disorders.15 Persistent ductus arteriosus, anomalous coronary arteries, mitral valve prolapse, persistent left superior vena cava, tetralogy of Fallot, double outlet right ventricle and total anomalous pulmonary venous return have been described in patients with the Holt–Oram syndrome.10,14–20 Interestingly, numerous individuals with familial Holt–Oram syndrome showed only ECG abnormalities without structural cardiac anomalies.18 Conduction disorders may occur, mostly affecting the atrioventricular node. Also sinus node dysfunction, bradycardia, atrial fibrillation, atrioventricular block, RBBB, Wolf-Parkinson-White syndrome and even sudden cardiac death have been reported.1,7,14 Hypoplastic and ectopic peripheral vessels are common, posing as a serious challenge in getting vascular access in these patients.14

A variety of morphological and anatomic criteria in conjunction of genetic analyses have led to the recognition of multiple heart-limb syndromes, with Holt–Oram being the most common.1,5,8,21 Diversity in the expression of abnormalities both skeletal and cardiovascular in the Holt–Oram syndrome seems to be attributed to different gene mutations.5

4. Conclusions

The association of a canal type VSD and mitral valve cleft with the Holt–Oram syndrome (case #4) has not been reported before to our knowledge.

Obviously, longevity of individuals with Holt–Oram syndrome depends upon the identification and treatment of their cardiac maladies. In our case series, nevertheless, morbidity was minimal.

Since the majority of the clinical information available is provided mostly by isolated reports, further epidemiological and genetic analyses are required to determine the incidence and categorize the different types of heart limb syndromes.

Conflict of interest

None.

Funding

None.

Ethical approval

Written informed consent was obtained from the patients for publication of these case reports and accompanying images. A copy of the written consent for each one separately is available for review by the Editor-in-Chief of this journal on request.

Author contributions

Gregory Chryssostomidis MD performed the literature review and drafted the manuscript. Meletios Kanakis MD performed the literature review and helped to draft the manuscript. Vassiliki Fotiadou MD, Theophili Kousi MD, Christos Apostolidis MD, and Prodromos Azariadis MD collected the data. Cleo Laskari MD helped for data analysis and interpretation; Andrew C. Chatzis MD involved in study concept and design, data analysis and interpretation, writing and editing the paper and is the guarantor of the work.

Key learning points.

-

•

The Holt–Oram syndrome exhibits a variety of congenital cardiac anomalies and not only atrioventricular septal defects.

-

•

Although the syndrome affects predominately the upper limbs, it is also associated with other skeletal malformations.

-

•

The trait may not be expressed in other family members.

References

- 1.Basson C.T., Solomon S.D., Weissman B., MacRae C.A., Poznanski A.K., Prieto F. Genetic heterogeneity of heart-hand syndromes. Circulation. 1995;91:1326–1329. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.91.5.1326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Holt M., Oram S. Familial heart disease with skeletal malformations. Br Heart J. 1960;22:236–242. doi: 10.1136/hrt.22.2.236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.McKusick V.A. 1959. Medical genetics. J Chronic Dis. 1960;12:1–202. doi: 10.1016/0021-9681(60)90134-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Srivastava D., Olson E.N. A genetic blueprint for cardiac development. Nature. 2000;407:221–226. doi: 10.1038/35025190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Basson C.T., Huang T., Lin R.C., Bachinsky D.R., Weremowicz S., Vaglio A. Different TBX5 interactions in heart and limb defined by Holt–Oram syndrome mutations. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96:2919–2924. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.6.2919. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Horb M., Thomsen G.H. Tbx5 is essential for heart development. Development. 1999;126:1739–1751. doi: 10.1242/dev.126.8.1739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Terrett J.A., Newbury-Ecob R., Cross G.S., Fenton I., Raeburn J.A., Young I.D. Holt–Oram syndrome is a genetically heterogenous disease with one locus mapping to human chromosome 12q. Nat Genet. 1994;6:401–404. doi: 10.1038/ng0494-401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Basson C.T., Cowley G.S., Solomon S.D., Weissman B., Poznanski A.K., Trail T.A. The clinical and genetic spectrum of the Holt–Oram syndrome (heart-hand syndrome) N Engl J Med. 1994;330:885–891. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199403313301302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yu Q., Shen Y., Chatterjee B., Siegfried B.H., Leatherbury L., Rosenthal J. ENU induced mutations causing congenital cardiovascular anomalies. Development. 2004;131:6211–6223. doi: 10.1242/dev.01543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sinha R., Nema D. Rare cardiac defect in Holt–Oram syndrome. Cardiovasc J Afr. 2012;23:e3–e4. doi: 10.5830/CVJA-2011-017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Böhm M. Holt–Oram Syndrome. Circulation. 1998;98:2636–2637. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.98.23.2636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Brockhoff C.J., Kober H., Tsilimingas N., Dapper F., Münzel T., Meinertz T. Holt–Oram Syndrome. Circulation. 1999;99:1395–1396. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.99.10.1395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Frota Filho J.D., Pereira W., Leiria T.L., Vallenas M., Leães P.E., Blacher C. Holt–Oram syndrome revisited. Two patients in the same family. Arq Bras Cardiol. 1999;73:429–434. doi: 10.1590/s0066-782x1999001100003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Shono S., Higa K., Kumano K., Dan K. Holt–Oram syndrome. Br J Anaesth. 1998;80:856–857. doi: 10.1093/bja/80.6.856. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sletten L.J., Pierpont M.E.M. Variation in severity of cardiac disease in Holt–Oram syndrome. Am J Med Gen. 1996;65:128–132. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1096-8628(19961016)65:2<128::AID-AJMG9>3.0.CO;2-O. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Singh B., Kariyappa M., Vijayalakshmi I.B., Nanjappa M.C. Holt–Oram syndrome associated with double outlet right ventricle: a rare association. Ann Pediatr Cardiol. 2013;6:90–92. doi: 10.4103/0974-2069.107245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kumar V., Agrawal V., Jain D., Shankar O. Tetralogy of Fallot with Holt–Oram syndrome. Indian Heart J. 2012;64:95–98. doi: 10.1016/S0019-4832(12)60021-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Vianna C.B., Miura N., Pereira A.C., Jatene M.B. Holt–Oram syndrome: novel TBX5 mutation and associated anomalous right coronary artery. Cardiol Young. 2011;21:351–353. doi: 10.1017/S1047951111000072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Miller A.B., Salcedo E.E., Bahler R.C. Prolapsed mitral valve associated with the Holt–Oram syndrome. Chest. 1975;67:230–232. doi: 10.1378/chest.67.2.230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Thai S., Boyella R., Arsanjani R., Thai H., Juneman E., Movahed M.R. Unusual combination of Holt–Oram Syndrome and persistent left superior vena cava. Congenit Heart Dis. 2011;7:E46–E49. doi: 10.1111/j.1747-0803.2011.00594.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Basson C.T. Holt–Oram syndrome vs. heart-hand syndrome. Circulation. 2000;101:E191. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.101.18.e191. Comment on Holt–Oram syndrome. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]