Abstract

Objective. To describe the development, implementation, and evaluation of a formal mentorship program at a college of pharmacy.

Methods. After extensive review of the mentorship literature within the health sciences, a formal mentorship program was developed between 2006 and 2008 to support and facilitate faculty development. The voluntary program was implemented after mentors received training, and mentors and protégés were matched and received an orientation. Evaluation consisted of conducting annual surveys and focus groups with mentors and protégés.

Results. Fifty-one mentor-protégé pairs were formed from 2009 to 2012. A large majority of the mentors (82.8%-96.9%) were satisfied with the mentorship program and its procedures. The majority of the protégés (≥70%) were satisfied with the mentorship program, mentor-protégé relationship, and program logistics. Both mentors and protégés reported that the protégés most needed guidance on time management, prioritization, and work-life balance. While there were no significant improvements in the proteges’ number of grant submissions, retention rates, or success in promotion/tenure, the total number of peer-reviewed publications by junior faculty members was significantly higher after program implementation (mean of 7 per year vs 21 per year, p=0.03) in the college’s pharmacy practice and administration department.

Conclusions. A formal mentorship program was successful as measured by self-reported assessments of mentors and protégés.

Keywords: mentorship, mentor, protégé, pharmacy, faculty

INTRODUCTION

The importance of formal mentorship programs to improve career development and satisfaction for those in the health sciences in general and for pharmacy faculty members specifically has been recognized for over a decade.1-5 Mentorship has been defined in many ways. The Institute of Medicine defined a mentor as a faculty advisor, career advisor, skills consultant, and role model.6 In a seminal article, Haines defined mentorship as an intentional activity whereby mentors execute their responsibilities with conscious effort in a nurturing relationship that has a goal of fostering the protégé’s potential.1 Ideally, mentors provide support, challenge, and vision to their protégés through a formal or informal process.

Western University of Health Sciences (WesternU) is a private institution comprised of 9 health sciences colleges. WesternU College of Pharmacy has offered a doctor of pharmacy (PharmD) program, since 2000, making it a relatively new college. The college’s initial focus was on teaching, with a commensurate high proportion of junior faculty members. In 2005, the college had 33 faculty members. During the Accreditation Council for Pharmacy Education (ACPE) self-study and accreditation team visit in 2005, it was determined that faculty members desired a formal mentorship program in addition to the informal mentoring that was already in place.

Formal mentorship programs are intended to provide a structure for new faculty members that informal mentoring lacks during the early phase after their academic appointment to help them better acclimate to the framework and culture of the institution and the profession.1,7 Given the potential benefit to faculty members, the college’s Faculty Orientation and Development (FOD) committee implemented a formal faculty mentorship program in August 2009 to complement existing informal mentoring activities. In this paper, we describe the development, implementation, and evaluation of this program.

METHODS

A Mentorship Task Force was created by the FOD committee in 2006, after an ACPE visit, to develop a proposal for a formal mentorship program for the college. An extensive literature review was conducted to identify the best current evidence regarding successful elements of existing mentorship programs within the health sciences or academic settings, and relevant mentorship literature that could be applied to pharmacy faculty members.1,8

The goal of the mentorship program was to support and facilitate junior faculty development through the provision of a formal mentoring process that matched mentors and protégés. The objectives of the program were for junior faculty members to develop a viable plan for future development, with timely and consistent progression as a faculty member, guidance on the path to successful promotion and/or tenure, and an awareness of the expectations in various categories of responsibilities in academia (ie, teaching, research and graduate supervision, practice, and service).

Haines suggested that a successful mentorship program include the following elements: (1) mentors with a strong desire to participate, (2) mentor/mentee pairs that have a common area of interest, (3) sufficient time for the pairs to spend together, and (4) mentors with a sufficient level of mentoring expertise.1 While our program was designed to meet the first and third of these features, a lack of senior faculty mentors initially limited our ability to have mentors with a matching area of interest and extensive expertise.

The WesternU College of Pharmacy’s mentoring program was based on 3 key features: voluntary participation, career mentorship, and full commitment. First, participation of both the mentor and protégé was voluntary to ensure that only willing participants with a desire to engage in the program were included, particularly mentors who were voluntarily involved in mentoring. Second, we adopted the concept of a career mentor rather than a scholarly mentor to guide the protégé towards professional success.9 However, the mentor did not have to be in the exact same field or department as the protégé. Feldman defines a career mentor as a senior faculty member who is primarily responsible for providing career guidance and support but who may not have expertise in the protégé’s scholarly or research area, vs a scholarly mentor who has expertise in the protégé’s scientific or scholarly area.9 Our preference for a career mentor was primarily because of the limited number of senior faculty members who shared common scientific or scholarly pursuits with potential protégés at the college at the time the program was initiated. The mentor’s role was intended to help provide direction to the protégé in their academic career, as well as help them achieve their self-defined goals while balancing the multiple facets of an academic faculty position. Furthermore, the mentor was important in helping the protégé understand organizational culture in order to assimilate more easily into the college, university, and profession.1 Finally, to ensure their full commitment to the program, the mentors and protégés were required to sign a formal written agreement that outlined specific concepts such as confidentiality, active listening, ability to terminate the agreement “without fault,” and willingness to meet at least every 3 months.

The criteria developed for the mentors included having: (1) the rank of associate professor within the college for at least 1 year, (2) a desire to mentor, (3) a willingness to undergo mentorship training and orientation, and (4) an understanding that they would work with no more than 2 protégés at one time. Mentors could be self- or peer nominated. They were required to complete an application form that asked about their willingness to participate, prior mentorship experience, reason for wanting to serve as a mentor, and amount of time willing to devote to mentoring. As a quality check, input was sought from potential protégés, and based on their feedback potential mentors could be deemed unsuitable for participation in the mentorship program at that time and/or future years.

The proposal for the mentor program was approved by the FOD committee and presented to faculty members. The task force was dissolved and a mentorship subcommittee of the FOD committee was established, with a timeline created to develop the logistics for implementation.

Once the subcommittee compiled a list of mentors, the members identified potential protégés according to the following criteria: (1) all new faculty members who started within the prior year, regardless of academic rank, and (2) all assistant professors, regardless of year of hire. As such, the subcommittee targeted primarily junior faculty members or faculty members who were new to the institution. Faculty members who were willing to become protégés completed a protégé mentorship needs survey and discussed their mentorship needs with their department chair, who then worked with the protégé to consider prospective mentors based on suitability and availability.

Required activities for the mentors and protégés included attending the orientation meeting together, discussing the protégé’s goals for the mentorship program at the start of the year, having a minimum of one face-to-face meeting every 3 months, and completing an annual assessment of the program. Protégé responsibilities included initiating meetings with the mentor, and applying what was learned from the mentor in practice. Based on the protégé’s needs, the mentor’s responsibilities included: assisting the protégé with networking with and identifying other possible mentors, identifying potential sources of research funds and providing support for the protégé in grant application writing; assisting the protégé in dealing with difficulties (eg, laboratory space, access to students, student complaints); directing the protégé to appropriate resources, including potential courses, workshops, and training, that might benefit the protégé in meeting his/her goals; and advising and critically reviewing the protégé’s teaching and research if appropriate for and applicable to the protégé’s needs and goals for the program.

While the department chair played a key role in orientation and mentoring of new faculty members, because of time constraints, it was not possible for the chair to act as a primary mentor for all faculty members in his/her department, and conflicted with the mentorship policy of having a maximum of 2 protégés per mentor. The department chair nonetheless played a fundamental role in the initial 6 months of new faculty hires, fulfilling both orientation and initial mentoring roles until a suitable mentor was identified and matched with the protégé.

At the start of the mentorship program in 2008, all mentors attended presentations and participated in workshops provided by an external speaker with expertise in academic pharmacy mentorship. Once the mentor-protégé pairings were completed in 2009, all participants were required to attend an orientation session in which the goals, objectives, and logistics of the formal mentorship program were reviewed. Both individuals signed the written agreement during the orientation session. The pairing was intended to be a 1-year commitment, however, it could continue for another year or more if both individuals indicated a desire to continue and signed the annual renewal agreement. To facilitate formal mentors referring protégés to other faculty members for mentoring in specific areas, all faculty members were asked to complete a survey to indicate the areas of expertise in which they would be willing to provide informal mentorship assistance. In order to recognize the mentor’s efforts, they were given service points that counted toward their annual performance review at a rate equivalent to that of service on a committee. As an incentive for the pairs to meet, the FOD committee provided a $50.00 meal allowance for each mentorship pair annually.

Program Evaluation

To evaluate the program, the subcommittee conducted separate focus groups for all mentors and protégés at the end of each year. Feedback was incorporated into changes in the program for the next year as part of the continuous quality improvement process. At least 80% of mentors and protégés participated each year.

The subcommittee also conducted annual surveys of the mentors and protégés to obtain feedback. Each survey instrument contained 4-point Likert scale questions about the benefits of and participants’ experiences with the program. Protégés also were asked to report achievement of outcomes related to participation in the program. Questions were tailored to the mentors and protégés separately and incorporated questions seeking feedback on the strengths of the program and areas for improvement. Several questions asked protégés about the suitability of the mentor, use of optional tools provided, and frequency of meetings.

A word cloud was generated to illustrate the main concepts identified from the written comments. The subcommittee also compared number of publications and grant submissions, faculty retention rates, and successful promotion and/or tenure 3 years before and 3 years after implementation of the mentorship program. Mean values were compared using t tests and proportions were compared using chi-square.

RESULTS

Over the first 4 years of the program, 51 faculty mentor-protégé pairs were created. The majority of protégés were from the pharmacy practice and administration department (73.5%); slightly more than half were male (56.9%); all were assistant professors. The majority of mentors were male (76.5%), and 51% were associate professors. Because the majority of protégés and mentors were male, most mentor-protégé pairs (72.5%) were same-gender pairings. Of the mixed-gender pairs, the majority consisted of a male mentor and female protégé; only 14.3% consisted of a female mentor and a male protégé.

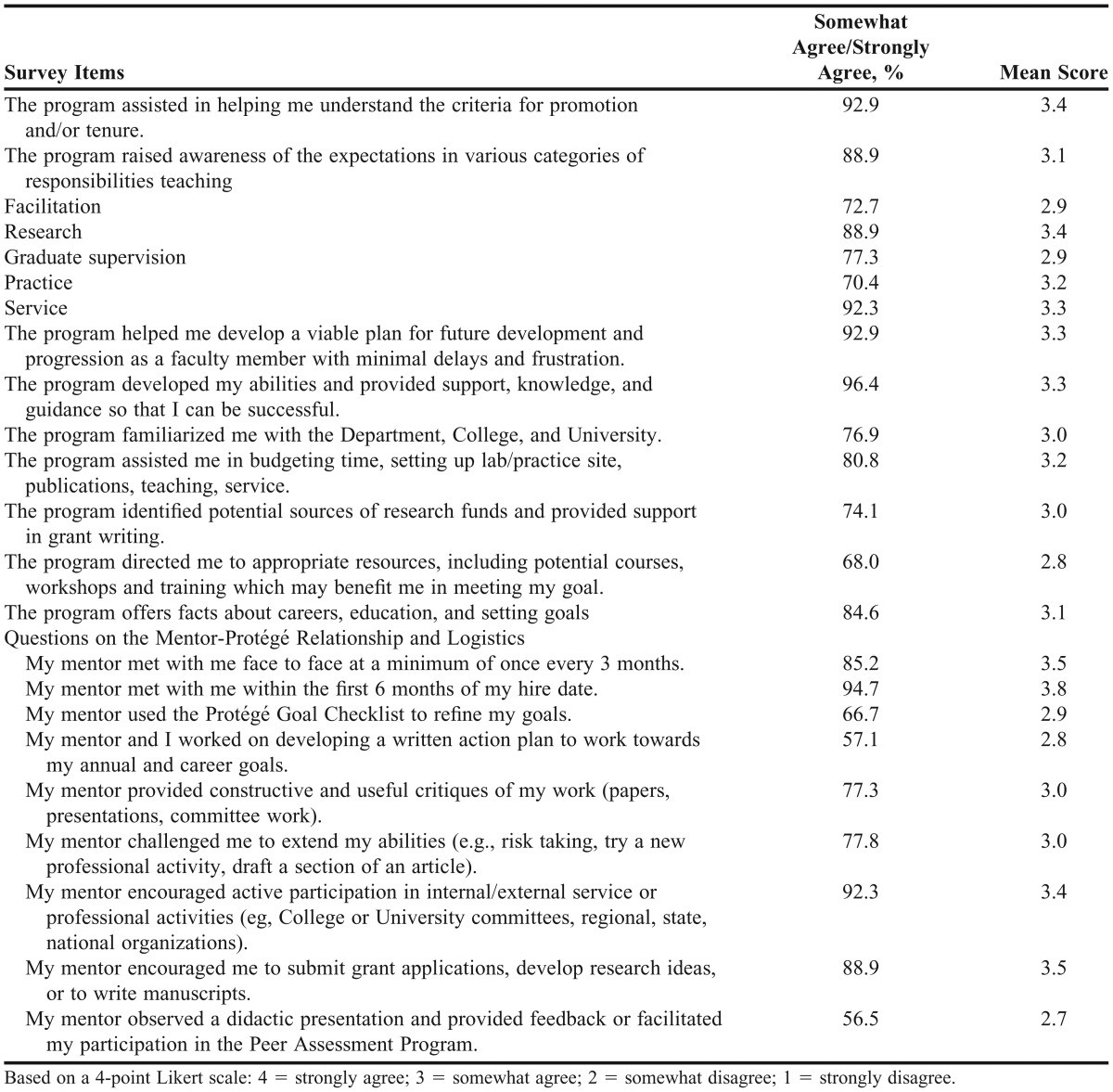

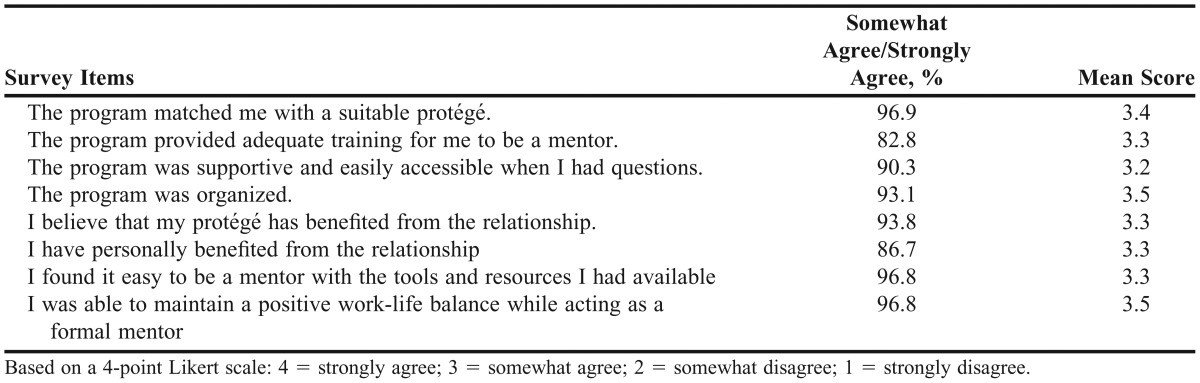

Responses from the 4 annual surveys (2010-2013) that were compiled for the mentors and protégés showed positive feedback in the majority of categories (Table 1 and Table 2). The overall survey response rate for the 4 years was 62.7% for mentors and 56.9 for protégés. The majority of mentors perceived the program to be successful, with 82.8% to 96.9% in agreement that the matches were suitable, training, organization, perceived benefit, resources, and work-life balance. Mean scores for all questions were above 3 points on a 4-point Likert scale.

Table 1.

Results of a Survey Administered to Protégés Who Participated in a Pharmacy Faculty Mentoring Program (n=29)

Table 2.

Results of a Survey Administered to Mentors Who Participated in a Pharmacy Faculty Mentoring Program (n=32)

The responses from the protégés also showed positive feedback in most categories except for 4 items with which <70% of respondents were in agreement. Three of these 4 questions reflected optional activities for the mentorship program, namely, having the mentor observe a lecture, using the protégé goal checklist, and developing a written plan. There was also <70% agreement for whether the program directed the protégé to appropriate resources (courses, workshops, training). Eight items received a mean score<3. These lower-scored items related to questions about whether the program raised awareness of facilitation responsibilities; explained graduate supervision responsibilities; familiarized the protégé with the department, college, or university; directed the protégé to appropriate resources; used the protégé goal checklist; used a written action plan; had the mentor challenge the protégé to extend his/her abilities, and had the mentor observe a lecture.

Written comments from the survey instruments indicated that mentors believed the program was well-structured and productive, and that protégés found the mentors willing and available. Using the written comments from the mentor and protégé survey instruments, a word cloud was constructed. The most frequently used words were help/helped, progress, committees, good, responsibility, progress, effective, different, relationship, and think.

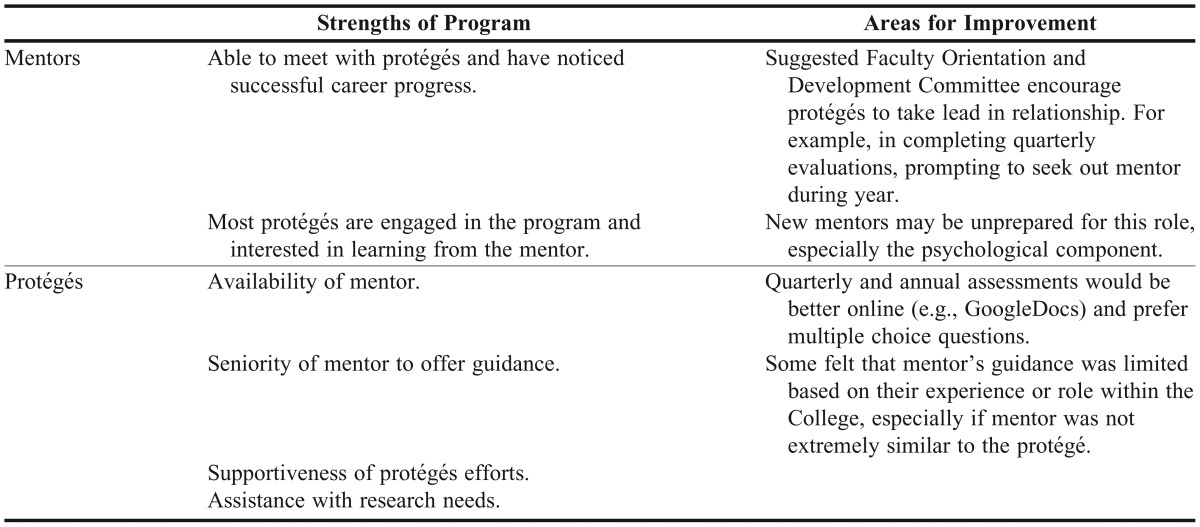

Suggestions for improvement from mentors and protégés included providing periodic reminders to “nudge” the pairs and remind them to meet and interact more often. Mentors also suggested that protégés needed to show more initiative and self-motivation, and that the Mentorship Subcommittee should provide some additional system for prompting mentor pairs to pursue and/or complete specific activities.

Feedback from focus groups with the protégés provided the following insights on their perceived needs. Protégés felt their needs were improving work/life balance, preparing for promotion and/or tenure, finding funding sources, and balancing the various aspects of being a faculty member (clinical practice, teaching, research, scholarship, service).

Mentors reported that their protégés needed guidance on managing their time, prioritizing, and achieving work-life balance. The mentors’ and protégés’ insights regarding strengths of the program and areas for improvement are summarized in Table 3.

Table 3.

Summary of Feedback from Mentor and Protégé Focus Groups

An increase in the total number of publications in the pharmacy practice department (mean of 33/year vs mean of 50/year, p=0.17) and among junior faculty members (mean of 18/year vs. mean of 26/year, p=0.16) were seen in the 3 years after implementation of the formal mentorship program when compared with rates during the 3 years before implementation (data not available for pharmaceutical sciences); however, the increases were not significant. There was a decrease in non-peer reviewed publications among junior faculty members and a significant increase in the total number of peer-reviewed publications for junior faculty protégés in the pharmacy practice department (mean of 7/year vs. mean of 21/year, p=0.03). However, there was no increase in the total number of grant submissions (mean of 34/year vs mean of 35/year, p=0.63), faculty retention rates, or promotion success rate (80% in both periods) after the mentorship program was implemented.

DISCUSSION

Over 90% of the protégés enrolled in a formal mentorship program reported that their mentors developed their abilities and provided support, knowledge, and guidance, which helped them to become more successful. Protégés also reported that mentors helped them develop a viable plan for progression as a faculty member and better prepared them for promotion and/or tenure. These findings are consistent with those of Zeind and colleagues, who found an improvement in self-perceived abilities among protégés.8

Mentors may fulfill specific purposes for their protégés, including teaching, sponsoring, encouraging, counseling, and befriending them.1 We found that the primary function of the mentors in our program was to give their protégés guidance on time management, prioritization, and work-life balance, all of which were needs only partially recognized by the protégés. Others have similarly found that psychosocial functions, which include acting as a role model, providing encouragement, and counseling are crucial.7,10 The mentors in this study also provided the traditional career mentoring functions, which include educating, coaching, sponsoring, and/or protecting the protégé.7 A systematic review found that the characteristics of successful mentoring relationships were reciprocity, mutual respect, clear expectations, personal connection, and shared values.11 Although we did not specifically assess participants for these attributes, the construct of our program through its voluntary participation and pair-matching process attempted to instill these values in the mentor partnerships.

The total number of peer-reviewed publications by junior faculty increased after implementation of the mentorship program. However, we did not find significant changes in other objective outcomes. Objectively documenting the success of a mentorship program is challenging because of the small sample size and the duration of followup that may be required to observe these changes. In addition, easily measurable outcomes that are not confounded with other faculty members’ improvement efforts are not readily available. Many departmental improvements also occurred during the same time as the implementation of the mentorship program. Determining the long-term impact of this formal mentorship program is premature at this time.

Formal mentorship programs have had conflicting results in terms of outcomes.1 Two meta-analyses found that positive outcomes were achieved with mentorship programs, however, the effect size was small.12,13 Ries and colleagues found that academic medicine faculty members who participated in a faculty development program with a mentoring component (n=113) were significantly more likely to stay at the institution (ie, higher retention rates) and had significantly higher academic success rates as measured by leadership and professional activities, honors and awards, contracts and grants, teaching and mentoring, and publications, as compared to nonparticipants (n=202).14

Through a comprehensive evaluation, we identified several areas for potential improvement in our mentor program. Mentors need to challenge protégés more effectively, as only 77.8% of protégés agreed with the statement “the mentor challenged me to extend responsibilities.” Mentors ideally should provide support, challenge, and vision to their protégés in order to stimulate their growth as academics and educators, and our mentors may need to be more assertive to accomplish this goal.1,8

Because the school is relatively young, only half of the mentors were professors; the other half were associate professors. Feedback from the survey instruments indicated that the protégés highly valued the seniority of their mentors. Typically, faculty mentors are 15-20 years senior to their protégé.1 Lack of senior faculty members can be a problem as less-experienced, mid-career level faculty members are taking on mentorship roles for which they may not be entirely prepared.8 Failed mentoring relationships have been characterized by mentor’s lack of experience, in addition to poor communication, lack of commitment, personality differences, perceived competition, and conflicts of interest.11 In our focus group sessions with mentors, group discussion allowed more senior mentors to share useful mentorship strategies with more junior mentors, helping them learn about mentorship strategies through real-life examples, and hopefully further developing their mentoring skills.

Although the program was successful despite the lack of more senior mentors, as the school matures, modifying the program to provide the best possible mentors for protégés will be important. The mentors were allowed to work with up to 2 protégés per year. However, because of the lack of senior faculty members with a breadth of experience, some protégés may not have had ideal matches and were assigned to more junior faculty mentors. The subcommittee advised all mentors to refer their protégés to other internal and external resources and people rather than feeling they needed to meet all of the protégé’s needs. Drawing on several individuals for mentorship in different areas, with one primary career mentor to guide the protégé overall, was the model that we targeted. Some protégés reported that their mentors were not perfect matches, however, and these protégés appeared to expect a single mentor rather than capitalizing on multiple individuals. This perspective has also been reported by others.3,10

The scarcity of senior female faculty members in academics and leadership positions decreases a female protégé’s chances of receiving effective mentorship and thus, female faculty members might need to use multiple mentors to meet the needs of both academic mentoring as well as specific gender-related needs.3,15 While the vast majority of matches in this study were same-gender pairs, there were some mixed-gender pairs, mostly with a male mentor and female protégé, given that we had a preponderance of male mentors. Although no protégés commented on the lack of female mentors, the school should reflect on the need for female faculty members in senior and leadership roles to help with mentoring female protégés more effectively.

Based on qualitative research at 2 large universities, the characteristics of effective protégés included being open to feedback and active listening, respectful of mentor’s time and feedback, being responsible, paying attention to timelines, and taking responsibility for “driving the relationship.”11 The feedback from the mentors in our study suggests that the protégés were not as independent, and relied on the mentors to drive the relationship rather than the other way around. In a guide for mentees, Zerzan and colleagues suggest that mentees should “manage up” – meaning that the mentee should takes responsibility for his or her part in the mentoring relationship and be the leader of the relationship. Managing up has been suggested to facilitate the mentor in helping the protégé, which makes the relationship more successful.16,17 This was the intention in our program, however, protégés were still more passive than desired and this aspect of the program requires more attention.

CONCLUSION

A comprehensive mentorship program demonstrated highly promising initial results in subjective, self-reported assessments by mentors and protégés, as well as an objectively measured increase in the total number of peer-reviewed journal publications. We plan to continue evaluating our program to examine long-term objective outcomes. The evaluation process identified areas for program improvement, including the need to expand mentor training, encourage protégés to take a greater lead in the mentoring partnerships, and examine the possibility of mid-career mentorship because the program focuses on junior faculty members. Overall, the outcomes suggest that this mentorship program served as an essential component of the school’s faculty development program.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We would like to thank Dr. Wallace Murray for contributions to the original proposal for this paper, and Drs. David Min and Steve O’Barr, and Ms. Anne Ly for assistance with compiling some of the necessary data to conduct the analyses for this paper.

REFERENCES

- 1.Haines ST. The mentor-protégé relationship. Am J Pharm Educ. 2003;67(3):Article 82. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bickel J, Lark V. Encouraging the advancement of women: mentorship is key. JAMA. 2000;283(5):671. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Duda RB. Mentorship in academic medicine: a critical component for all faculty and academic advancement. Curr Surg. 2004;61(3):325–327. doi: 10.1016/j.cursur.2003.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Boyce EG, Burkiewicz JS, Haase MR, et al. Clinical faculty development. Pharmacotherapy. 2009;29(1):124–126. doi: 10.1592/phco.29.1.124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Boyce EG, Burkiewicz JS, Haase MR, et al. ACCP white paper: essential components of a faculty development program for pharmacy practice faculty. Pharmacotherapy. 2009;29(1):127. doi: 10.1592/phco.29.1.127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.National Academy of Sciences, National Academy of Engineering, Institute of Medicine. Advisor, Teacher, Role Model, Friend: On Being a Mentor to Students in Science and Engineering. Washington, DC: National Academy Press; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fuller K, Maniscalco-Feichtl M, Droege M. The role of the mentor in retaining junior pharmacy faculty members. Am J Pharm Educ. 2008;72(2):Article 41. doi: 10.5688/aj720241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zeind CS, Zdanowicz M, MacDonald K, Parkhurst C, King C, Wizwer P. Developing a sustainable faculty mentoring program. Am J Pharm Educ. 2005;69(5):Article 100. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Feldman MD, Arean PA, Marshall SJ, Lovett M, O’Sullivan P. Does mentoring matter: results from a survey of faculty mentees at a large health sciences university. Med Ed Online. 2010;15:5063–5070. doi: 10.3402/meo.v15i0.5063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Taylor CA, Taylor JC, Stoller JK. The influence of mentorship and role modeling on developing physician-leaders: views of aspiring and established physician-leaders. J Gen Intern Med. 2009;24(10):1130–1134. doi: 10.1007/s11606-009-1091-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Straus SE, Johnson MO, Marquez C, Feldman MD. Characteristics of successful and failed mentoring relationships: a qualitative study across two academic health centers. Acad Med. 2013;88(1):82–89. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e31827647a0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Eby LT, Allen TD, Evans SC, Ng T, DuBoois D. Does mentoring matter? A multidisciplinary meta-analysis comparing mentored and non-mentored individuals. J Vocat Behav. 2008;72(2):254–267. doi: 10.1016/j.jvb.2007.04.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Allen TD, Eby LT, Poteet ML, Lentz E, Lima L. Career benefits associated with mentoring for protégés: a meta-analysis. J Appl Psychol. 2004;89(1):127–136. doi: 10.1037/0021-9010.89.1.127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ries A, Wingard D, Garnst A, Larsen C, Farrell E, Reznik V. Measuring faculty retention and success in academic medicine. Acad Med. 2012;87(8):1046–51. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e31825d0d31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Metzger AH, Hardy YM, Jarvis C, et al. Essential elements for a pharmacy practice mentoring program. Am J Pharm Educ. 2013;77(2):Article 23. doi: 10.5688/ajpe77223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zerzan JT, Hess R, Schur E, Phillips RS, Rigotti N. Making the most of mentors: a guide for mentees. Acad Med. 2009;84(1):140–144. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e3181906e8f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Drucker P. Managing oneself. Harv Bus Rev. 1999;77(2):64–74,185. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]