Abstract

Objective:

Bankart and Hill–Sachs lesions are often associated with anterior shoulder dislocation. The MRI technique is sensitive in diagnosing both injuries. The aim of this study was to investigate Bankart and Hill–Sachs lesions with MRI to determine the correlation in occurrence and defect sizes of these lesions.

Methods:

Between 2006 and 2013, 446 patients were diagnosed with an anterior shoulder dislocation and 105 of these patients were eligible for inclusion in the study. All patients were examined using MRI. Bankart lesions were classified as cartilaginous or bony lesions. Hill–Sachs lesions were graded I–III using a modified Calandra classification.

Results:

The co-occurrence of injuries was high [odds ratio (OR) = 11.47; 95% confidence interval (CI) = 3.60–36.52; p < 0.001]. Patients older than 29 years more often presented with a bilateral injury (OR = 16.29; 95% CI = 2.71–97.73; p = 0.002). A correlation between a Bankart lesion and the grade of a Hill–Sachs lesion was found (ρ = 0.34; 95% CI = 0.16–0.49; p < 0.001). Bankart lesions co-occurred more often with large Hill–Sachs lesions (OR = 1.24; 95% CI = 1.02–1.52; p = 0.033).

Conclusion:

If either lesion is diagnosed, the patient is 11 times more likely to have suffered the associated injury. The size of a Hill–Sachs lesion determines the co-occurrence of cartilaginous or bony Bankart lesions. Age plays a role in determining the type of Bankart lesion as well as the co-occurrence of Bankart and Hill–Sachs lesions.

Advances in knowledge:

This study is the first to demonstrate the use of high-quality MRI in a reasonably large sample of patients, a positive correlation of Bankart and Hill–Sachs lesions in anterior shoulder dislocations and an association between the defect sizes.

A shoulder dislocation is a traumatic event with an incidence of around 24 per 100 000 in North America.1,2 Anterior shoulder dislocation is the most common direction, and most patients are male.1–4 The highest incidence (48 per 100 000) was found between the ages of 20 and 29 years.2 Anterior dislocation causes a typical impression fracture on the posterior humeral head, known as a Hill–Sachs lesion.5,6 The labrum or the glenoid itself may also be damaged; these injuries are known as Bankart lesions.7

Although Hill–Sachs lesions can be found in 47–100% of all patients with first-time or recurrent shoulder dislocation, a distinction must be drawn between cartilaginous and bony Bankart lesions.8–13 Cartilaginous lesions occur more often than bony ones.14 However, Bankart and Hill–Sachs lesions do not necessarily occur simultaneously. In 2006, Widjaja et al15 reported that, if one of the lesions was identified, the other was 2.67 times as likely to be present. Yet, this result failed to reach statistical significance because of the small sample size. Griffith et al10 evaluated CT scans and found a weak correlation between glenoidal bone loss and the size of the Hill–Sachs lesion (p = 0.030). However, the more frequently occurring cartilaginous Bankart lesion was not considered in this study.

The aim of the present study was to evaluate the association between defect sizes in Hill–Sachs and bony as well as cartilaginous Bankart lesions after anterior shoulder dislocation using MRI. We hypothesized that there exists a higher correlation than previously thought between temporal occurrence and defect size of the lesions. The results of this study should help to improve diagnostic and therapeutic procedures.

METHODS AND MATERIALS

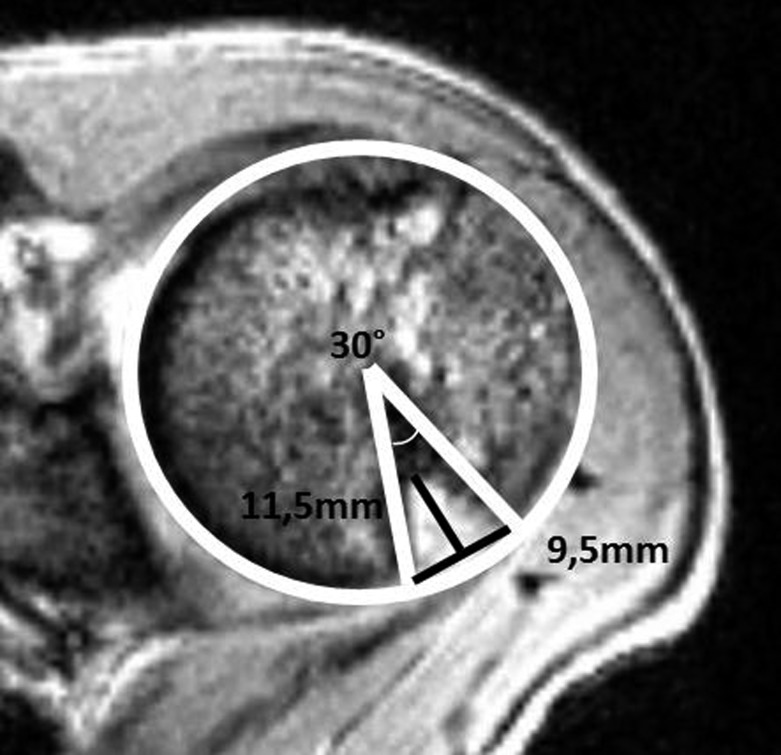

We retrospectively assessed all patients who were diagnosed with shoulder dislocation at our institution between 2006 and 2013. Inclusion criteria were anterior shoulder dislocation, availability of pre-operative MRI, the absence of acute or former concomitant injuries to the investigated shoulder joint and no previous shoulder surgery. All demographic data and injury mechanisms were drawn from patients' charts and the hospital's electronic database. First traumatic and recurrent shoulder dislocations were reported. Radiographs and MR images were analysed by radiologists and trauma surgeons in regard to Hill–Sachs and Bankart lesions and the absence of concomitant injuries (i.e. fractures, rotator cuff injuries, superior labrum anteroposterior and anterior labral periosteal sleeve avulsion). Defect sizes for Bankart lesions were measured using the Gyftopoulos circle method16 and graded using Itoi's classification.17 Hill–Sachs lesions were measured using the modified Cetik method9 (Figure 1) and were classified according to the Calandra classification.12

Figure 1.

Hill–Sachs lesion (d = 11.5 mm, t = 9.5 mm, a = (30°/360°) × 100 = 8.3%).

Trauma mechanisms were classified as “sport”, “fall”, “severe trauma” (i.e. high-energy trauma) or “unknown”. Statistical analysis was carried out using SAS® v. 9.2 (TS Level 2M3; SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC); Pearson's correlation, Wilcoxon and Kruskal–Wallis tests as well as logistic regression were used. Means, standard deviation, range, odds ratios (ORs) and 95% confidence intervals (95% CIs) are reported. A p ≤ 0.050 was considered statistically significant. Graphs were drawn using Microsoft Excel® (Microsoft, Redmond, WA).

RESULTS

Demographic

446 patients were diagnosed with shoulder dislocation between 1 January 2006 and 1 July 2013. In total, 105 patients (110 shoulder joints) were included in the study.

Females were significantly older than males (p = 0.003). Patients with recurrent shoulder dislocation were significantly younger (p = 0.010), and younger age correlated positively with recurrent shoulder dislocation (OR = 1.05; 95% CI = 1.02–1.09; p = 0.006) (Table 1). Most patients were found in the age group between 20 and 29 years (n = 44).

Table 1.

Demographic data

| Demographics | n | % | Age (years) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Male | 85 | 82.5 | 32.6 ± 14.0 (16–74) |

| Female | 20 | 17.5 | 48.2 ± 20.3 (17–80) |

| First traumatic event | 77 | 70.0 | 38.5 ± 17.9 (16–80) |

| Recurrent dislocation | 33 | 30.0 | 28.3 ± 9.7 (17–65) |

Injury mechanisms could be established in 36.00% (n = 40) of cases. 11 patients fell at ground level (27.50%). 10 patients (25.00%) were injured during sport activities, and 19 patients (47.50%) suffered severe trauma (high-energy insult). The frequency of the different injury mechanisms varied significantly across the age groups (p = 0.023). Younger patients were injured during sports, whereas older ones suffered severe trauma.

Radiological assessment via MRI

Bankart lesion

In 80 cases (73.00%), a Bankart lesion was diagnosed (Table 2). A cartilaginous lesion (Itoi Grade I) was found in 57 patients (71.25%), whereas a bony lesion, in which <25.00% of the glenoid surface was damaged (Itoi Grade II), was found in 22 patients (27.50%). Just 1 patient (1.25%) was diagnosed with glenoid surface damage exceeding 25% (Itoi Grade III). Patients older than 30 years more often suffered from bony lesions, whereas younger patients presented with cartilaginous damage (OR = 4.19; 95% CI = 1.44–12.22; p = 0.013). An association between the presence of a cartilaginous or bony Bankart lesion on first or recurrent shoulder luxation was not found (OR = −0.88; 95% CI = 0.31–2.49; p = 1).

Table 2.

The presence and the absence of Hill–Sachs and Bankart lesions within a study population

| Lesions | No Bankart lesion (n) | Bankart lesion (n) | Total (n) |

|---|---|---|---|

| No Hill–Sachs lesion (n) | 13 | 5 | 18 |

| Hill–Sachs lesion (n) | 17 | 75 | 92 |

| Total (n) | 30 | 80 | 110 |

Hill–Sachs lesion

In 92 cases (84.00%), a Hill–Sachs lesion was diagnosed. The mean defect sizes were 4.3 ± 3.2 mm (range = 0–15.1 mm) in depth and 13.1 ± 4.0 mm (range = 5.6–29.0 mm) in width. About 16.80 ± 5.00% (range = 7.30–35.30%) of the humeral head circumference was damaged. There was an association between depth, width and percentage of humeral head circumference damage. The width of the lesion and the size of the defect zone increased with increasing depth (p = 0.001) (Table 3).

Table 3.

Correlation of depth, width and defect zones in Hill–Sachs lesions based on the Calandra classification

| Grade | n | % | Depth (t) (mm) |

Width (d) (mm) |

Defect zone (a) (%) |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | SD | Min–max | Mean | SD | Min–max | Mean | SD | Min–max | |||

| I | 25 | 27 | 0.5 | 0.8 | 0–1.9 | 16.7 | 4.0 | 9.8–26.9 | 13.1 | 2.8 | 7.2–19.7 |

| II | 61 | 66 | 5.1 | 1.7 | 2.5–10.0 | 16.3 | 4.8 | 7.3–29.2 | 12.7 | 3.8 | 5.6–21.9 |

| III | 6 | 7 | 11.6 | 2.0 | 9.6–15.1 | 22.2 | 7.7 | 12.1–35.3 | 16.9 | 7.2 | 8.6–29.7 |

| p < 0.001 | p < 0.001 | p < 0.001 | |||||||||

Max, maximum; min, minimum; SD, standard deviation.

The recurrence of shoulder luxation was not associated with a higher number of Hill–Sachs lesions (OR = 0.62; 95% CI = 0.22–1.78; p = 0.405). Similarly, defect sizes in patients with recurrent shoulder luxation did not differ significantly from those with first event shoulder luxation (depth, p = 0.700; width, p = 0.250; humeral head circumference damage, p = 0.550).

Association of Bankart and Hill–Sachs lesions

The occurrence of both Hill–Sachs and Bankart lesions is associated with anterior shoulder dislocation. The prevalence of Hill–Sachs lesions was found to be 84.00% (n = 92), and the prevalence of a Bankart lesion was measured at 73.00% (n = 80).

The co-occurrence of these injuries is 11.47 times (OR = 11.47, 95% CI = 3.60–36.52, p < 0.001) more frequent than the occurrence of only one of these lesions in patients with anterior shoulder luxation. A subgroup analysis revealed additional significant results (Table 4).

Table 4.

Subgroup analysis of co-occurrence of Hill–Sachs and Bankart lesions

| Subgroup | OR | 95% CI | p-value | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patients with first traumatic event (n = 77) | 16.71 | 3.24–86.33 | <0.001 | ||||||||

| Patients with recurrent shoulder dislocation (n = 33) | 10.22 | 1.50–69.76 | 0.023 | ||||||||

| Patients ≤29 years (n = 57) | 8.63 | 1.88–39.56 | 0.004 | ||||||||

| Patients >29 years (n = 53) | 16.29 | 2.71–97.73 | 0.002 |

CI, confidence interval; OR, odds ratio.

Furthermore, extensive Bankart lesions revealed higher damage in the humeral head (Table 5).

Table 5.

Correlation of Bankart lesion (BL) with depth, width and defect zone of Hill–Sachs lesion (HSL)

| BL | HSL depth (mm) |

HSL width (mm) |

HSL defect zone (%) |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | SD | Min–max | Mean | SD | Min–max | Mean | SD | Min–max | |

| 0 | 1.7 | 2.4 | 0–7.6 | 9.1 | 8.9 | 0–26.9 | 7.4 | 7.1 | 0–19.7 |

| I | 4.2 | 3.1 | 0–12.0 | 15.3 | 5.5 | 0–25.8 | 12.1 | 4.6 | 0–21.9 |

| II | 4.4 | 4.1 | 0–15.1 | 17.5 | 8.1 | 0–35.3 | 12.8 | 6.2 | 0–29.7 |

| p < 0.001 | p < 0.001 | p = 0.015 | |||||||

Max, maximum; min, minimum; SD, standard deviation.

Logistic regression also revealed a positive association between the depth of Hill–Sachs lesions and the likelihood of a co-occurring Bankart injury (Table 5). For every 1-mm increase in Hill–Sachs lesion depth, the likelihood of suffering a concomitant Bankart lesion increases by a factor of 1.24 (OR = 1.24; 95% CI = 1.02–1.52; p = 0.033).

DISCUSSION

The results of the present study support previously reported findings. In terms of trauma mechanisms, sport activities were only a cause in male patients. Although the prevalence of Bankart lesions in the present study was lower than that in other studies (67.00% vs 83.00–100.00%), the prevalence of Hill–Sachs lesions was comparable (83.50% vs 47.00–100.00%).8,18–21 Different factors determining the size of a Hill–Sachs lesion are discussed in the literature: upward forces that cause a shoulder dislocation are cited alongside ligament instability. In cases of ligament hyperlaxity, less force is necessary to cause a shoulder dislocation,17,22 and, in consequence, the size of any Hill–Sachs lesion is smaller owing to lower shear and impression forces. This may explain the lower probability of suffering a Hill–Sachs lesion in the recurrence group. On the other hand, normal ligament strength and therefore higher forces are responsible for bigger Hill–Sachs lesions and are thereby responsible for decreased shoulder stability and recurrent shoulder dislocations.23,24 However, this approach accounts for only a moderate proportion of the study population. Because of the retrospective design of this study, it was not possible to rule out hyperlaxity as a suspected reason. Our results therefore remain in contrast to previously published findings that proved recurrent shoulder dislocations as a cause for increased defect sizes of Hill–Sachs lesions, similar to the effect of recurrent shoulder dislocation on the extent of a Bankart lesion.9,25 In contrast to previously published reports on the correlation analysis of recurrent shoulder dislocations and secondary injuries, we compared lesion sizes for a first event with those of recurring events. Significant differences in defect size were not seen in our group, but a subgroup analysis of recurrent shoulder dislocations may provide support for the findings cited above. Nevertheless, the specific threshold for the negative influence of defect size on shoulder stability has not yet been defined, and this discussion is ongoing. Sekiya et al26 showed that defect sizes of 12.50% of humeral head circumference are biomechanically relevant and lesions bigger than 25.00% of the humeral head circumference have a high impact on shoulder instability: they easily cause shoulder dislocation. In contrast to the findings of Sekiya et al, we could not demonstrate an association between recurrent shoulder dislocations and the occurrence or size of a Hill–Sachs lesion. With regard to the co-occurrence of Bankart and Hill–Sachs lesions, we found that the likelihood of suffering both injuries simultaneously is greater by a factor of 11.47 than the likelihood of suffering either lesion in isolation. Our results therefore provide confirmation of a finding that was first described by Widjaja et al15 in 2006. These authors reported on a reduced likelihood factor of 2.67 regarding the occurrence of a concomitant Bankart or Hill–Sachs lesion when either one of them was diagnosed. Although the prevalence of both injuries was similar in this cohort, the frequency of recurrent shoulder dislocations was higher. This may explain why Widjaja et al found an association between the co-occurrence of these injuries in patients with recurrent anterior shoulder dislocations. Nevertheless, results regarding the likelihood factor were not significant because of a small sample size (n = 61) and a small number of first-time dislocations (n = 15). Armitage et al22 postulated that recurrent shoulder joint instability correlates positively with the occurrence of Hill–Sachs and bony Bankart lesions. Our data support this hypothesis in so far as patients presenting with a first traumatic event had a significantly higher probability of co-occurrence of these injuries. The probability of co-occurrence in recurrent luxation was lower but still significant in the present cohort. Further studies on this topic should perform a subgroup analysis of concomitant injuries that influence shoulder stability in co-occurring Bankart and Hill–Sachs lesions.

It was found that older (≥29 years) patients are at a higher risk of co-occurrence of Bankart and Hill–Sachs lesions. To our knowledge, no studies have addressed the issue of age as an important risk factor in the occurrence of either one of the lesions, but it is extremely interesting to have found a cut-off that helps improve diagnostics and treatment. It was also found that bony Bankart lesions are associated with bigger Hill–Sachs lesions. For clinicians relying on plain radiographs, this finding may assist in determining the right diagnostic and therapeutic algorithms. Our findings provide confirmation of the findings of Griffith et al,21 who investigated 233 patients using CT and presented comparable results. However, the present study is based on MRI findings and, unlike Griffith et al, we were also able to investigate labral tears. Gyftopoulos et al16 demonstrated the accuracy of MRI in the assessment of glenoid bone loss in a study of 14 cadaveric shoulders. We found that the size of the Hill–Sachs lesion predicts the presence of a Bankart lesion. The bigger the Hill–Sachs lesion, the more likely it is that an accompanying Bankart lesion will be found. This is important, as it can be assumed that a Bankart lesion is very likely if a large Hill–Sachs lesion is seen on plain radiographs. It should also be noted that Hill–Sachs lesions were significantly bigger when co-occurring with bony rather than cartilaginous Bankart lesions.

In treatment of a Bankart or a Hill–Sachs lesion, it is important to consider the co-occurring injury. Just focusing on the Bankart lesion is not acceptable. Both Boileau et al27 and Voos et al28 showed that patients having a higher grade Hill–Sachs lesion who were treated solely for their Bankart lesion showed a higher rate of recurrent shoulder dislocation. Furthermore, it was noted that young age, hyperlaxity of ligaments and the use of fewer than three suture anchors in labrum repair were risk factors for recurrent shoulder dislocations. Burkhart and Danaceau,29 who coined the term “articular arc length mismatch”, were the first to focus on the ratio of glenoid surface to the humeral head. The “engagement” of the Hill–Sachs lesion causes subluxation and increases the risk of shoulder re-dislocation. This was described in more detail by Yamamoto et al30 and Scheibel et al14 and termed the contact surface of the “glenoid track”.13

The present study investigates the co-occurrence of Hill–Sachs and Bankart lesions through high-quality MRI findings in a good-sized sample of patients. The crucial point in all the findings reported here is the decreased contact area between the humeral head and glenoid surface, which is important for shoulder stability. A decrease in contact surface is given in concomitant Hill–Sachs and Bankart lesions. The bigger both lesions are, the smaller the contact surface and, consequently, the higher the risk of recurrent dislocation. It is therefore extremely important to evaluate the size of both lesions as well as their localization. This study might help to focus attention on the prevalence and severity of these correlating injuries. We have provided information on the co-occurence of both lesions and the extent to which the size of either lesion relates to the accompanying injury.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The work presented here involved the collaboration of all authors. KH, RvH and CW defined the research theme, designed the study, collected and analysed the data, interpreted the results and wrote the paper. TD, HA and RP worked on interpretation and discussed the analyses, interpretation and presentation. HCP gave final critical approval. All authors have contributed to, seen and approved the manuscript.

The article was proofread by Proof-Reading-Service.com, Letchworth Garden City, United Kingdom.

REFERENCES

- 1.Leroux T, Wasserstein D, Veillette C, Khoshbin A, Henry P, Chahal J, et al. Epidemiology of primary anterior shoulder dislocation requiring closed reduction in Ontario, Canada. Am J Sports Med Nov 2013. Epub ahead of print. doi: 10.1177/0363546513510391 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 2.Zacchilli MA, Owens BD. Epidemiology of shoulder dislocations presenting to emergency departments in the United States. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2010; 92: 542–9. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.I.00450 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dodson CC, Cordasco FA. Anterior glenohumeral joint dislocations. Orthop Clin North Am 2008; 39: 507–18. doi: 10.1016/j.ocl.2008.06.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Westin CD, Gill EA, Noyes ME, Hubbard M. Anterior shoulder dislocation. A simple and rapid method for reduction. Am J Sports Med 1995; 23: 369–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hill H, Sachs M. The groove defect of the humeral head. A frequently unrecognized complication of dislocations of the shoulder joint. Radiology 1940; 35: 690–700. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gill TJ, Zarins B. Open repairs for the treatment of anterior shoulder instability. Am J Sports Med 2003; 31: 142–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bankart AS. Recurrent or habitual dislocation of the shoulder-joint. Br Med J 1923; 2: 1132–3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Antonio GE, Griffith JF, Yu AB, Yung PS, Chan KM, Ahuja AT. First-time shoulder dislocation: high prevalence of labral injury and age-related differences revealed by MR arthrography. J Magn Reson Imaging 2007; 26: 983–91. doi: 10.1002/jmri.21092 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cetik O, Uslu M, Ozsar BK. The relationship between Hill-Sachs lesion and recurrent anterior shoulder dislocation. Acta Orthop Belg 2007; 73: 175–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Griffith JF, Antonio GE, Yung PS, Wong EM, Yu AB, Ahuja AT, et al. Prevalence, pattern, and spectrum of glenoid bone loss in anterior shoulder dislocation: CT analysis of 218 patients. AJR Am J Roentgenol 2008; 190: 1247–54. doi: 10.2214/AJR.07.3009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rowe CR, Patel D, Southmayd WW. The Bankart procedure: a long-term end-result study. J Bone Joint Surg Am 1978; 60: 1–16. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Calandra JJ, Baker CL, Uribe J. The incidence of Hill–Sachs lesions in initial anterior shoulder dislocations. Arthroscopy 1989; 5: 254–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wiedemann E, Jager A, Nebelung W. Pathomorphology of shoulder instability. [In German.] Orthopade 2009; 38: 16–20, 22–3. doi: 10.1007/s00132-008-1350-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Scheibel M, Kraus N, Gerhardt C, Haas NP. Anterior glenoid rim defects of the shoulder. [In German.] Orthopade 2009; 38: 41–8, 50–3. doi: 10.1007/s00132-008-1354-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Widjaja AB, Tran A, Bailey M, Proper S. Correlation between Bankart and Hill–Sachs lesions in anterior shoulder dislocation. ANZ J Surg 2006; 76: 436–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1445-2197.2006.03760.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gyftopoulos S, Hasan S, Bencardino J, Mayo J, Nayyar S, Babb J, et al. Diagnostic accuracy of MRI in the measurement of glenoid bone loss. AJR Am J Roentgenol 2012; 199: 873–8. doi: 10.2214/AJR.11.7639 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ito H, Takayama A, Shirai Y. Radiographic evaluation of the Hill–Sachs lesion in patients with recurrent anterior shoulder instability. J Shoulder Elbow Surg 2000; 9: 495–7. doi: 10.1067/mse.2000.106920 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sugaya H, Moriishi J, Dohi M, Kon Y, Tsuchiya A. Glenoid rim morphology in recurrent anterior glenohumeral instability. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2003; 85-A: 878–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Norlin R. Intraarticular pathology in acute, first-time anterior shoulder dislocation: an arthroscopic study. Arthroscopy 1993; 9: 546–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yiannakopoulos CK, Mataragas E, Antonogiannakis E. A comparison of the spectrum of intra-articular lesions in acute and chronic anterior shoulder instability. Arthroscopy 2007; 23: 985–90. doi: 10.1016/j.arthro.2007.05.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Griffith JF, Antonio GE, Tong CW, Ming CK. Anterior shoulder dislocation: quantification of glenoid bone loss with CT. AJR Am J Roentgenol 2003; 180: 1423–30. doi: 10.2214/ajr.180.5.1801423 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Armitage MS, Faber KJ, Drosdowech DS, Litchfield RB, Athwal GS. Humeral head bone defects: remplissage, allograft, and arthroplasty. Orthop Clin North Am 2010; 41: 417–25. doi: 10.1016/j.ocl.2010.03.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hovelius L, Augustini BG, Fredin H, Johansson O, Norlin R, Thorling J. Primary anterior dislocation of the shoulder in young patients. A ten-year prospective study. J Bone Joint Surg Am 1996; 78: 1677–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rowe CR. Prognosis in dislocations of the shoulder. J Bone Joint Surg Am 1956; 38-A: 957–77. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Li H, Liu Y, Li Z, Li C, Dong X, Zhu J. Correlation analysis between recurrent anterior shoulder dislocation and secondary intra-articular injuries. [In Chinese.] Zhongguo Xiu Fu Chong Jian Wai Ke Za Zhi 2012; 26: 308–12. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sekiya JK, Wickwire AC, Stehle JH, Debski RE. Hill–Sachs defects and repair using osteoarticular allograft transplantation: biomechanical analysis using a joint compression model. Am J Sports Med 2009; 37: 2459–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Boileau P, Villalba M, Héry J-Y, Balg F, Ahrens P, Neyton L. Risk factors for recurrence of shoulder instability after arthroscopic Bankart repair. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2006; 88: 1755–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Voos JE, Livermore RW, Feeley BT, Altchek DW, Williams RJ, Warren RF, et al. Prospective evaluation of arthroscopic bankart repairs for anterior instability. Am J Sports Med 2010; 38: 302–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Burkhart SS, Danaceau SM. Articular arc length mismatch as a cause of failed bankart repair. Arthroscopy 2000; 16: 740–4. doi: 10.1053/jars.2000.7794 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Yamamoto N, Itoi E, Abe H, Minagawa H, Seki N, Shimada Y, et al. Contact between the glenoid and the humeral head in abduction, external rotation, and horizontal extension: a new concept of glenoid track. J Shoulder Elbow Surg 2007; 16: 649–56. doi: 10.1016/j.jse.2006.12.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]