Abstract

The most common thyroid malignancy is papillary thyroid cancer (PTC). Mortality rates from PTC mainly depend on its aggressiveness. Geno- and phenotyping of aggressive PTC has advanced our understanding of treatment failures and of potential future therapies. Unraveling molecular signaling pathways of PTC including its aggressive forms will hopefully pave the road to reduce mortality but also morbidity from this cancer. The mitogen-activated protein kinase and the phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase signaling pathway as well as the family of RAS oncogenes and BRAF as a member of the RAF protein family and the aberrant expression of microRNAs miR-221, miR-222, and miR-146b all play major roles in tumor initiation and progression of aggressive PTC. Small molecule tyrosine kinase inhibitors targeting BRAF-mediated events, vascular endothelial growth factor receptors, RET/PTC rearrangements, and other molecular targets, show promising results to improve treatment of radioiodine resistant, recurrent, and aggressive PTC.

Keywords: BRAF, P13/Akt, Papillary thyroid cancer, Signaling, Tyrosine kinase, VEGF.

INTRODUCTION

The most common well differentiated thyroid cancer (TC) is papillary thyroid cancer (PTC) and is usually indolent with a 10 year survival rate of approximately 93% [1]. Distant metastases at the time of diagnosis are reported in up to 4% of patients with PTC [2-4]. After surgery patients with PTC are followed by basal and thyroid stimulating hormone (TSH)-stimulated thyroglobulin (Tg) determination, and by neck ultrasonography [5-7]. Histologic variants of PTC can show aggressive features, clinically noted as recurrent TC, resistance to radioactive iodine therapy, propensity to metastasize, and often lower 10 year survival rates, if the aggressive TC is not a microcarcinoma [8]. Interestingly, gene expression profiles of papillary thyroid microcarcinomas may not be different from those of PTCs [9]. Also, familial PTC has a similar clinical and prognostic behaviour, apart from multifocality, when compared with sporadic PTC [10].

Ganly et al. [11] recently reported 100% 10 year disease specific survival rates for patients with classic PTC and 96% for those with tall cell variant PTC. In that study, 2.4% of patients with PTCs with tall cell variant of features developed poorly differentiated or anaplastic TC (ATC). It is important to consider clinico-pathological aspects in combination with molecular features [12-14]. In various geographicareas of the world, different diagnostic criteria for aggressive PTC have been used, leading to discrepancies among pathologists and clinicians. More recently, more consensus regarding the diagnostic criteria of aggressive PTC has been reached [15-17]. Among the most aggressive types of PTC are: diffuse sclerosing variant (accounting of up to 6% of all PTC), tall cell variant (accounting of up to 11% of all PTC), and insular TC (less than 1% of all PTC) [15].

Molecular signaling (or signal transduction) is important for the knowledge of the core biological processes in any type of cancer including TC [18, 19]. The definition of the responses of normal and cancerous cells to environmental and endogenous signals may elucidate the intimate mechanisms at the basis of malignancy formation, progression, invasion and spread to distant metastases. The development of novel anticancer therapies could be allowed by the detailed knowledge of cancer cell signaling [20-28]. However, such data should be used in combination with clinico-pathological data to achieve practical use with hopefully improvement in the care of cancer patients [12-14, 17]. In the last decades, the knowledge about signaling pathways in patients with TC has grown rapidly. One such pathway is the TSH-dependent signaling system.

The thyroid follicular cell, being an endocrine cell, has many “identity-specific” signaling systems, pertinent to the multitude of its endocrine functions and correlated with its status of differentiation. Malignant transformation (e.g., loss of Tg or sodium-iodide symporter [NIS] expression) are associated with specific alterations in these endocrine function-related systems, that usually coexist with derangements in signaling pathways unrelated to the endocrine character. In this review, we will focus our contribution on aggressive PTC and membrane receptor-associated signaling systems. Intracellular (and nuclear) receptor signaling is also an essential part of cell regulation, as emphasized by the role of the PAX8/peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor (PPAR)γ oncoprotein in follicular thyroid cancer’s (FTC) [29] and the presence of thyroid hormone receptors and functional estrogen in PTC’s and FTC’s which can be stimulated by endocrine disrupting, estrogen mimicking chemicals such as PCB180 and PCP mixtures [30], but we will not comment on this subject.

Herein, we categorize signaling in TC cells that occurs after the activation of plasma membrane receptors and their downstream effector systems, i.e., (1) enzyme-coupled receptors and downstream pathway elements and (2) G-protein coupled receptors (GPCR’s) and associated proteins. Signal sensing and propagation in TC cells are activated by miscellaneous, not yet completely elucidated mechanisms, for example, those responsible for responses of thyrocytes to generic environmental cellular insults (as hypoxia [31] or hydrogen peroxide/reactive oxygen species) [32-35]. Overactivation of pyruvate kinase M2 is necessary for aerobic glycolysis and may provide a selective growth advantage for PTC cells. Reactive oxygen species possibly enhance the phosphatidylinositol-3-kinase (PI3K) and mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) pathways. Hypoxia-inducible factor 1 is regulated by hypoxia and via growth factor signaling pathways including the PI3K pathway [34].

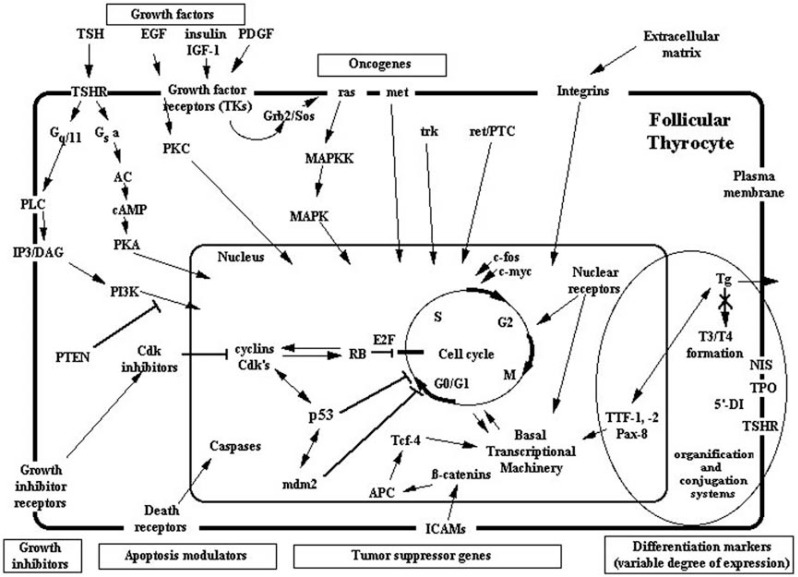

We here review the most important signaling systems operative in TC cells and their interrelationship with other elements that control thyrocyte growth, apoptosis, and differentiation [36] (Fig. 1).

Fig. (1).

Molecular mechanisms of oncogenesis for non-medullary thyroid cancers (adapted with permission from Springer publisher).

Koch CA, Sarlis NJ. Thyroid cancer. In: Encyclopedic Reference “Molecular Mechanisms of Disease”-Endocrinology and Diabetes section (Textbook). Editor-in-Chief: F. Lang, Section Editors: S.R. Bornstein and D. LeRoith. Springer Publisher GmbH Berlin, Germany (online and in print; 2009, Tome:LXXXVI; doi: 10.1007/978-3-540-29676-8_1743; web address: http://www.springerlink.com/content/g7t66546 38x483g8/fulltext.html (ref. 36 in this manuscript)

Abbreviations: AC: adenyl cyclase, APC: adenomatous polyposis coli gene, cAMP: cyclic AMP, Cdk: cyclin-dependent kinase, DAG: diacylglycerol, 5’-DI: 5’-deiodinase, EGF: epidermal growth factor, ICAM: intercellular adhesion molecules, IGF-1: insulin-like growth factor-1, IP3: inositol triphosphate, MAPK: mitogen-activated protein kinase, MAPKK: MAPK kinase, NIS: sodium/iodide symporter, PDGF: platelet-derived growth factor, PI3: phosphatidylinositol-3-phosphokinase, PKA: protein kinase A, PKC: protein kinase C, PLC: phospholipase C, PTEN: phosphatase-tensin gene product, RB: retinoblastoma-gene protein, T3: triiodothyronine, T4: thyroxine, Tg: thyroglobulin, TSH: thyroid stimulating hormone, TSHR: TSH receptor, TPO: thyroid peroxidase, TTF: thyroid specific transcription factor.

MOLECULAR SIGNALING VIA PLASMA MEMBRANE RECEPTORS IN TC

GPCRs Associated Proteins, and Downstream Effectors

TSH Receptor (TSHR) and G-proteins

TSHR is the par excellence thyroid-specific GPCR, that contains seven-transmembrane domain receptors, and transduces the signal of ambient TSH (its ligand) to the thyrocyte [37]. Upon binding onto TSHR, TSH activates thyroid function, proliferation and differentiation through the activation of both G-protein- and inositol triphosphate (IP3)/phospholipase C (PLC)-dependent pathways.

After thyroidectomy, the suppression of endogenous pituitary TSH production by thyroid hormone treatment in patients with (papillary) TC leads to decreased morbidity and mortality. TSH exposure desensitizes TSHR-dependent signaling through the activation of a G-protein-coupled kinase (GRK), which phosphorylates TSHR [38]. Then, the phosphorylated TSHR attracts arrestins (proteins which inhibit the G- protein dependent signaling cascade) (see below) [39, 40]. If TSHR expression is lost or diminished, as seen in some TCs, TSH does not influence the growth of these tumors [18].

Activating TSHR mutations are rarely identified in TC [41-43].

The downstream delivery of the TSHR signal is achieved via the G-proteins which are submembranic and associated with the TSHR. G-proteins consist of an α–subunit and a βγ–subunit dimer. Gs α variant is the predominant type of the α-subunit in thyrocytes. The regulators of G-protein signaling proteins are able to accelerate the hydrolysis of GTP to GDP, also enhancing the kinetics of termination of the hormone signal [44]. From mutations at either of two “hot spots”, i.e. residues Arg201 or Gln227, it can derive hyperactivity of Gs α. Gs α mutations have been described rarely in TC and in autonomously functioning benign thyroid adenomas [45, 46]. The thyroid manifestations of McCune-Albright syndrome, a sporadic genetic disease caused by a post-zygotic activating mutation of the Gs α gene, that include TC (such as clear cell TC), and benign thyroid neoplasms (in particular follicular adenomas), corroborate these observations [47, 48].

TSHR activation also induces stimulation of Gi. Activation of the Gi /G0 system through the stimulation of the P2-purinergic receptor by extracellular adenosine triphosphate induces activation of phospholipase A2 (PLA2) in thyroid FRTL-5 cells [49]. PLA2 hydrolyzes the sn-2 ester bond of cellular phospholipids and produces a free fatty acid and a lyso-phospholipid, which are both lipid signaling molecules; once activated, this signaling pathway is a point of “cross-talk” with pathways activated by mitogens and growth factors (see below). Arachidonic acid (i.e.,5,8,11,14-eicosatet- raenoic acid) is the free fatty acid frequently produced, which is the precursor of the eicosanoid family that includes prostaglandins, thromboxanes, leukotrienes and lipoxins [50]. In a model utilizing rat thyroid cells transformed by the RET/PTC oncogenes, Mariggio et al. [51] demonstrated that the control of the cell growth of thyroid tumor is mediated by PLA2 group IV isoform alpha. Arachidonate 5 lipoxygenase expression and activity mediates invasion via metalloproteinase-9 induction in aggressive PTC [52]. Cyclooxygenase-2 expression increases with age and may play a role in aggressive PTC [53].

Regarding other G-proteins in thyroid oncogenesis, Metastin signaling does not involve Akt/protein kinase B (PKB) [54], and its receptor, Gq/11 -coupled receptor, is overexpressed in PTC, and activates MAPK in the ATC-derived cell line ARO.

GRK regulates the homologous desensitization of different GPCR. The expression of GRK 2,3,5, and 6 can desensitize the TSHR in vitro. GRK 2 expression was found to be decreased in cold thyroid nodules when compared to tissue surrounding the nodules [55].

Protein Kinase A (PKA), Adenylyl cyclase (AC), and cAMP Response Element-binding Protein (CREB)

AC activation via TSHR signaling leads to production of cAMP. Some subsets of TC have increased AC activity, others decreased cAMP production [18]. cAMP activates PKA, which belongs to a large family of proteins, that are heterotetramers, and consist of two regulatory (R-) subunits and two catalytic (C-) subunits. The dissociation of the C-subunits is caused by the binding of cAMP to the R-subunits. Serine and threonine residues of various acceptor proteins are phosphorylated by the catalytic sites on the two dissociated C-subunits, both in the cytoplasm and the nucleus. Inactivating germline mutations of the PKA RIα subunit gene occur in a subgroup of TC and in a multiple neoplasia syndrome, called Carney complex [56, 57].

PKA phosphorylates several substrates, as the p85 phosphoprotein, in thyrocytes, thus leading to enhancement of the interaction between p21/Ras and PI3K. At the same time, cAMP can also inhibit Raf1 kinase signaling decreasing Raf1 availability to Ras. Once activated, PKA also phosphorylates other proteins, as CREB, which is a nuclear transcription factor belonging to the large family of leucine zipper DNA binding proteins and binds to cAMP response elements. In TC, CREB expression is strongly downregulated, but probably not related to the functional state of differentiation of the malignancy, as evaluated by NIS expression levels [58]. Praja2, a widely expressed really interesting new gene ligase, degrades the regulatory subunits of PKA, thereby controls the strength and duration of PKA signaling in response to cAMP. Praja2 is markedly overexpressed in differentiated TC and shows an inverse correlation with the malignant phenotype of the tumor [59].

Protein kinase C (PKC) and PLC

TSHR activation stimulates pathways which depend on the PLC-γ, via coupling of the receptor to members of the Gq/11 family [60]. The activity of the plasma membrane PLC is increased in neoplastic thyroid tissue, correlating to the degree of tumoral de-differentiation [61]. PLC stimulation causes the hydrolysis of phosphatidylinositol 4,5-biphosphate, which generates diacylglycerol (DAG) and IP3. IP3 increases the concentration of intracellular ionized calcium (iCa++) permitting its release from the endoplasmic reticulum, while DAG activates PKC, which in turn, under certain conditions, can also be activated directly by iCa++ , and phosphorylates several target proteins [62]. Usually, the activation of the PKA pathway antagonizes the PI3-iCa++ -PKC pathway in thyroid tissue.

Enzyme-coupled Membrane Receptor Systems

The Receptor-tyrosine Kinases (RTK’s) and Their Downstream Effectors

RTK’s are membrane receptors with intrinsic tyrosine kinase (TK) activity. These receptors phosphorylate downstream intracellular substrate proteins or can undergo auto- phosphorylation [63]. The elements of the Ras – MAPK pathway, PI3K-PKB/Akt system, PLC-γ, and RAS/GTPase- activating proteins are downstream molecules along RTK-dependent pathways [19, 64].

Insulin-like growth factor-1 increases the expression of vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) in TC cells, through both AP-1/hypoxia inducible factor-1α- and PI3K-dependent mechanisms [65]. High expression of VEGF in TC seems to correlate with an increased risk of recurrence, lymph node metastases, and advanced tumor stage [66]. Neuropilin-2 is a coreceptor for VEGF-D and correlates with lymph node metastases in PTC [67].

Epidermal growth factor (EGF) activates the PKC pathway. Overexpression of the EGF receptor in BRAF wild-type PTC may represent a biomarker for aggressive PTC [68]. Of note, another growth factor family member, platelet derived growth factor (PDGF) receptor B is upregulated in clinically aggressive PTC [69]. The effects of PDGF ligands are influenced by inflammatory cytokines. Interleukin (IL)-6 expression is related with aggressiveness in PTC [70]. Interestingly, concomitant Hashimoto’s thyroiditis in patients with PTC seems to correlate, with low recurrence and less aggressive clinical stage, whereas Graves’s disease is associated with larger and multifocal TC [43, 71]. Chemokines and their receptors appear to be involved in several steps of tumorigenesis and progression in TC. Oncogenes can upregulate chemokine (C-X-C) motif ligand 10 (CXCL10), thereby further stimulating proliferation and invasion. PPARγ thiazolidinediones can inhibit growth of PTC by inhibiting CXCL10 secretion in thyroid follicular cells [72]. C-X-C chemokine receptor 4 (CXCR4) expression and BRAF mutation status may in concert lead to a more aggressive phenotype in PTC [73]. Young patients with PTC with intense CD-40 ligand expression often have aggressive, multifocal, and recurrent TC [74]. The frequency of regulatory T cells and tumor associated lymphocytes in primary PTC seems to correlate with more aggressive disease [75]. The prevalence of nuclear location of CD30L and the proportion of CD30L+ cells are involved in aggressiveness of PTC with CD30L/CD30 signaling being activated especially in an autocrine fashion [76].

The nuclear factor kappa-B (NF-kB) proteins, transcription factors, have an important role in human malignancies including TC by controlling proliferative and antiapoptotic signaling pathways. Oncogenic proteins such as RET/PTC, RAS, and BRAF, can induce NF-kB activation in TC. NF-kB inhibitors can induce antiproliferative effects and apoptosis and may be of great benefit in aggressive TC [77]. RET/PTC3 is markedly prevalent in PTC induced by radiation and associated with a greater tumor size, a more aggressive phenotype, the solid variant, and a more advanced stage at diagnosis [78].

TC cells also express other RTK’s, as fibroblast growth factor receptor 1 (FGFR)-1 (or Flg) and FGFR-3, c-erbB-2/HER-2/neu, hepatocyte growth factor receptor (HGFR)/c-met, a spliced variant of c-ret, VEGF receptor (VEGFR), and neurotrophic tyrosine receptor kinase-1 (a.k.a. trkA, or p75/LNGFR) [18].

Her2/neu protein overexpression in papillary and follicular TC may predict metastatic disease and the application of trastuzumab (Herceptin) in such patients may be beneficial [79, 80].

Occult papillary TC’s (“microcarcinomas”) have been shown to overexpress HGFR which is perhaps involved in early stages of PTC formation [81]. An immunohistochemical study of thyroid nodules, papillary and other TC revealed that the combination HGF/c-met/STAT3/pSTAT3/P13K was expressed by all PTC [82]. In a Middle Eastern population with PTC, c-MET had been found overexpressed immunohistochemically in 37% of cancers and was significantly associated with more aggressive behaviour [83].

RAS and the MAPK kinase/MAPK Pathway

The family of RAS oncogenes encode 21 kDa G-proteins that influence MAPK and P13K signaling pathways in TC. The p21/ras oncogene protein product is Ras, which has intrinsic GTPase activity. Point mutations in codons 12, 13, and 61 of the RAS oncogene have been found in TC. In particular, point mutations in codon 61 cause repression of GTPase activity and are correlated with aggressiveness of PTC. Overall, RAS mutations are found in approximately 10% of PTC and in much higher numbers in progressive TC [19, 84].

The MAPK pathway is involved in differentiation, cell proliferation, and survival. Upon activation, subsequent molecular events further augment the tumorigenic drive of this pathway (Fig. 1).

The activation of p38/MAPK, a serine/threonine kinase responsible for the mediation of stress-activated cell responses, as “generic” responses to ionizing radiation, heat, ultraviolet light, and osmotic shock, can also depend on RAS and selected RTK’s [85]. Cytokines and other inflammatory mediators can activate the p38 MAPK kinase pathway. Ribosome protein S6 kinase-B, nuclear proteins, as CREB and activating transcription factor are the final effectors of p38 MAPK signaling [86].

The Raf kinases (i.e. Raf-1 and b-Raf) are downstream from RAS. BRAF is a member of the Raf protein family and activates the MAPK pathway. Earlier studies have shown a correlation between BRAF mutation V600E and aggressiveness of PTC but recent studies have challenged this concept, suggesting that BRAF mutation in PTC is a later subclonal event and that no correlation between BRAF-positive primary focus of papillary microcarcinoma and more aggressive or recurrent disease exists [64, 87-89].

RTK’s can activate not only the RAS-MAPK pathway, but also PI3K signaling, leading to the generation of D-3-phosphoinositides, as phosphatidylinositol-3,4,5-trisphos- phate. The role of this pathway in TC has first been recognized when patients with Cowden syndrome caused by a germline mutation in the PTEN gene were found to have FTC. Increased expression and activation of Akt has been demonstrated to activate the P13/Akt pathway. In this setting, Akt-1 and Akt-2 are the most important genes [19, 90-92]. Activation of Akt leads to a phosphorylation cascade with involvement of multiple proteins, including mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR), and ultimately to increased cell growth and reduced apoptosis. Rapamycin, which is a strong immunosuppressant, inhibits IL-2 dependent T-cell proliferation. mTOR signaling is activated in aggressive PTC [93]. The occurrence of multiple tumors including PTC in one patient should make one consider a hereditary tumor syndrome [94, 95].

The TK-associated Receptors (TKAR’s) and Their Downstream Effectors

TKAR’s represent a large family of receptors, lacking an intrinsic TK domain, but able to activate different intracellular TK’s after ligand binding, thus leading indirectly to the phosphorylation of downstream target substrates.

Cytokine receptors activation leads to phosphorylation and activation of Janus kinases (Jak), which subsequently phosphorylate and activate differentially members of the signal transducer and activator of transcription (STAT) proteins, leading to the regulation of transcription of specific genes, along the cascade of the Jak-STAT pathway [18].

IL-6 and its receptor IL-6R have been evidenced in less than 50% of PTC studied [96]. STAT-3, the downstream effector of the IL-6R system, appeared much better correlated with the expression of HGFR (MET) in these PTC [96].

The members of the tumor necrosis factor receptor family are closely related to TKAR’s. These heterotrimeric receptor systems are also collectively known as “death receptors” as are responsible for induction of apoptosis (or programmed cell death). The caspase recruitment domain is part of the downstream effectors of the death receptor-dependent signaling cascade. Caspases constitute the common final pathway of all apoptotic signals, leading to cell lysis [97]. Fas (or CD95/Apo-1), one of these “death receptors”, in concert with its ligand (FasL) initiates a number of processes through the activation of caspases, along the pathway of cell death [98]. The antiapoptotic protein survivin plays a role in many human cancers and tumors [99]. The upregulation of survivin expression has been suggested as a marker of dedifferentiation or aggressiveness in PTC [100]. Similarly, FasL correlates with a more aggressive phenotype of PTC, when expressed in high levels [101]. Apoptosis could ensue either through infiltrating cytotoxic lymphocytes or as part of the natural course of rapidly growing tumors outstripping their growth resources, in TC.

The Serine-threonine Kinase (STK) Receptors and Their Downstream Effectors

The ligands for these receptors are members of the transforming growth factor- β (TGF-β) superfamily. The STK receptor-dependent signaling systems have an essential role during embryonic development, and participate in adult tissue homeostasis [102]. The expression of the ligands belonging to this family, and their cognate receptors, including TGF-β, activin, and bone morphogenetic proteins’s, has been identified in both normal and neoplastic thyroid tissues [18, 103].

The “downstream” signal transduction cascade includes the phosphorylation and thus the activation of cytoplasmic small mother against decapentaplegic (SMAD) proteins (SMAD-1 to -8). It is believed that the mechanism of TGF-β-induced growth inhibition (eventually leading to apoptosis) in normal thyrocytes involves reduction in the levels of p27/kip1 (a cyclin-dependent kinase [cdk] inhibitor), which is overridden in malignant thyrocytes by NF-κB activation [104]. Overexpression (immunohistochemically) of cell cycle regulator cyclin D1 and estrogen receptor β and underexpression of p27 may predict lymph node metastases in PTC [105, 106].

MicroRNAs

Small noncoding RNA genes composed of 21 to 25 nucleotides, called microRNAs, can inhibit expression levels of genes at the transcriptional and posttranslational levels. In PTC, miR-221, miR-222, and miR-146b have been identified as the most upregulated miRNAs and strongly correlate with extrathyroidal invasion and drug resistance [18, 107, 108]. miR-1 silences chemokine CXCR4, which is important for lymph node metastases. Through cyclin D1, miR-31 and miR-130b regulate proliferation, apoptosis, and cell cycle [109].

Potential Molecular Targets for the Treatment of Aggressive PTC

Considering the high frequency of BRAF mutations in PTC, the development of BRAF inhibitors is appealing. The agent BAY43-9006 not only inhibits mutant V600EBRAF but also FLT-3, c-KIT, VEGFR-2, VEGFR-3, and PDGFRβ kinases [19]. Lenvatinib is a TK inhibitor targeting FGFR1-4, RET, VEGFR1-3, KIT, and PDGFRβ with response rates around 50%. Various other agents have completed phase II and/or III studies and are listed and reviewed in [19]. Clinically meaningful increases in iodine uptake and retention in subgroups of patients with thyroid cancer that is (initially) refractory to radioiodine, can occur with certain agents such as MAPK kinase 1 and 2 inhibitor selumetinib, perhaps with greater effectiveness if TC is RAS mutant (BRAF) positive [28]. A recent meta-analysis suggested a modest effect of the VEGF-targeted therapy with sorafenib in patients with radioiodine-refractory differentiated TC, while it showed a potential therapeutic effect in Chinese patients with PTC and radioiodine refractory pulmonary metastases [110, 111].

SUMMARY

One of the most well studied endocrine neoplasms at the molecular level is PTC. As the mortality rates for TC mainly depend on its aggressiveness including ineffectiveness of surgical and radioiodine therapy, it is critical to understand the molecular pathobiology of cancer cell signaling of this “model malignancy”, considering that PTC has many ligands, cognate receptors, and downstream effectors.

The growing knowledge of the elements of these systems and the interaction between them and other constituents of the cell proliferation machinery (protein synthesis and degradation, cell cycle, gene transcription) has led to novel therapies including the use of vandetanib, motesanib, axitinib, cabozantinib, sorafenib, sunitinib, pazopanib, lenvatinib, selumetinib, and others in treating patients with progressive TC of medullary, papillary and follicular subtypes.

Hopefully, molecular profiling of (aggressive papillary) TC will help identify patients with advanced TC who could benefit from new treatment modalities. MAPK kinase inhibitors such as selumetinib increase the effectiveness of radioiodine therapy, particularly in patients with RAS mutations [3, 27].

Future trials will likely involve combined therapeutics and targets to overcome drug resistance [112]. The challenge of any future TC therapy will remain to unravel cooperative pathways that influence tumorigenesis and tumor progression, even in individuals of families with identical genetic germline defects and/or environmental risk factors [113, 114].

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Declared none.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The author SB has nothing to declare. CAK has served on the Advisory Board for Bayer Pharmaceuticals.

ABBREVIATIONS

- PTC

= Papillary thyroid cancer

- TC

= Thyroid cancer

- TSH

= Thyroid stimulating hormone

- Tg

= Thyroglobulin

- ATC

= Anaplastic TC

- NIS

= Sodium-iodide symporter

- PPARγ

= Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor

- FTC

= Follicular thyroid cancer

- GPCR’s

= G-protein coupled receptors

- MAPK

= Mitogen-activated protein kinase

- PI3K

= Phosphatidylinositol-3-kinase

- TSHR

= TSH receptor

- IP3

= Inositol triphosphate

- PLC

= Phospholipase C

- GRK

= G-protein-coupled kinase

- PLA2

= Phospholipase A2

- PKB

= Protein kinase B

- AC

= Adenylyl cyclase

- PKA

= Protein kinase A

- CREB

= cAMP response element-binding protein

- PKC

= Protein kinase C

- DAG

= Diacylglycerol

- iCa++

= Intracellular ionized calcium

- RTK’s

= Receptor-tyrosine kinases

- TK

= Tyrosine kinase

- VEGF

= Vascular endothelial growth factor

- EGF

= Epidermal growth factor

- PDGF

= Platelet derived growth factor

- IL

= Interleukin

- CXCL10

= Chemokine (C-X-C) motif ligand 10

- CXCR4

= C-X-C chemokine receptor 4

- NF-kB

= Nuclear factor kappa-B

- FGFR

= Fibroblast growth factor receptor

- HGFR

= Hepatocyte growth factor receptor

- VEGFR

= VEGF receptor

- mTOR

= Mammalian target of rapamycin

- TKAR’s

= TK-associated receptors

- Jak

= Janus kinases

- STAT

= Signal transducer and activator of transcription

- IL-6R

= IL-6 receptor

- STK

= Serine-threonine kinase

- TGF-β

= Transforming growth factor- β

- SMAD

= Small mother against decapentaplegic

REFERENCES

- 1.Carcangiu ML, Zampi G, Pupi A, Castagnoli A, Rosai J. Papillary carcinoma of the thyroid.A clinicopathologic study of 241 cases treated at the University of Floence Italy. Cancer . 1985; 55(4):805–828. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19850215)55:4<805::aid-cncr2820550419>3.0.co;2-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hefer T, Joachims HZ, Hashmonai M, Ben-Arieh Y, Brown J. Highly aggressive behavior of occult papillary thyroid carcinoma. J. Laryngol. Otol. 1995;109(11):1109–1112. doi: 10.1017/s0022215100132165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Reiners C. Thyroid cancer in 2013: Advances in our understanding of differentiated thyroid cancer. Nat. Rev. Endocrinol. 2014;10(2):69–70. doi: 10.1038/nrendo.2013.247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sabra MM, Dominguez JM, Grewal RK, Larson SM, Ghossein RA, Tuttle RM, Fagin JA. Clinical outcomes and molecular profile of differentiated thyroid cancers with radioiodine-avid distant metastases. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2013;98(5):E829–836. doi: 10.1210/jc.2012-3933. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Antonelli A, Miccoli P, Fallahi P, Grosso M, Nesti C, Spinelli C, Ferrannini E. Role of neck ultrasonography in the follow-up of children operated on for thyroid papillary cancer. Thyroid. 2003;13(5):479–484. doi: 10.1089/105072503322021142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Spinelli C, Bertocchini A, Antonelli A, Miccoli P. Surgical therapy of the thyroid papillary carcinoma in children experience with 56 patients < or =16 years old. J. Pediatr. Surg. 2004;39(10):1500–1505. doi: 10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2004.06.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Antonelli A, Miccoli P, Derzhitski VE, Panasiuk G, Solovieva N, Baschieri L. Epidemiologic and clinical evaluation of thyroid cancer in children from the Gomel region (Belarus). World. J. Surg. 1996;20(7):867–871. doi: 10.1007/s002689900132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kuo EJ, Goffredo P, Sosa JA, Roman SA. Aggressive variants of papillary thyroid microcarcinoma are associated with extrathyroidal spread and lymph-node metastases a population-level analysis. Thyroid. 2013;23(10):1305–1311. doi: 10.1089/thy.2012.0563. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kim HY, Park WY, Lee KE, Park WS, Chung YS, Cho SJ, Youn YK. Comparative analysis of gene expression profiles of papillary thyroid microcarcinoma and papillary thyroid carcinoma. J. Cancer. Res. Ther. 2010;6(4):452–457. doi: 10.4103/0973-1482.77103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pinto AE, Silva GL, Henrique R, Menezes FD, Teixeira MR, Leite V, Cavaco BM. Familial vs sporadic papillary thyroid carcinoma matched case comparative study showing similar clinical/prognostic behavior. Eur. J. Endocrinol. 2013;170(2):323–329. doi: 10.1530/EJE-13-0865. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ganly I, Ibrahaimpasic T, Rivera M, Nixon I, Palmer F, Patel SG, Tuttle RM, Shah JP, Ghossein R. Prognostic implications of papillary thyroid carcinoma with tall cell features. Thyroid. 2014;24(4):662–70. doi: 10.1089/thy.2013.0503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Niemeier LA, Kuffner AH, Song C, Carty SE, Hodak SP, Yip L, Ferris RL, Tseng GC, Seethala RR, Lebeau SO, Stang MT, Coyne C, Johnson JT, Stewart AF, Nikiforov YE. A combined molecular pathologic score improves risk stratification of thyroid papillary microcarci-noma. Cancer. 2012;118(8):2069–2077. doi: 10.1002/cncr.26425. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bansal M, Gandhi M, Ferris RL, Nikiforova MN, Yip L, Carty SE, Nikiforov YE. Molecular and histopathologic characteristics of multifocal papillary thyroid carcinoma. Am. J. Surg. Pathol. 2013;37(10):1586–1591. doi: 10.1097/PAS.0b013e318292b780. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Miccoli P, Miccoli M, Antonelli A, Minuto MN. Clinicopathologic and molecular disease prognostication for papillary thyroid cancer. Expert. Rev. Anticancer. Ther. 2009;9(9):1261–1275. doi: 10.1586/era.09.92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Roman S, Sosa JA. Aggressive variants of papillary thyroid cancer. Curr. Opin. Oncol. 2013;25(1):33–38. doi: 10.1097/CCO.0b013e32835b7c6b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kleiman DA, Beninato T, Soni A, Shou Y, Zarnegar R, Fahey TJ3rd. Does bethesda category predict aggressive features in malignant thyroid nodules?. Ann. Surg. Oncol. 2013;20(11):3484–3490. doi: 10.1245/s10434-013-3076-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Asioli S, Erickson LA, Sebo TJ, Zhang J, Jin L, Thompson GB, Lloyd RV. Papillary thyroid carcinoma with prominent hobnail features a new aggressive variant of moderately differentiated papillary carcinoma.A clinicopathologic immunohistochemical and molecular study of eight cases. Am. J. Surg. Pathol. 2010;34(1):44–52. doi: 10.1097/PAS.0b013e3181c46677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sarlis NJ, Benvenga S. Molecular signaling in thyroid cancer. Can. Treat. Res. 2004;122:237–264. doi: 10.1007/1-4020-8107-3_14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Omur O, Baran Y. An update on molecular biology of thyroid cancers. Crit. Rev. Oncol. Hematol. 2013;99(3):233–252. doi: 10.1016/j.critrevonc.2013.12.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Benvenga S. Emerging therapies in sight for the fight against dedifferentiated thyroid cancer. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2011;96(2):47–50. doi: 10.1210/jc.2010-2799. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Antonelli A, Fallahi P, Ferrari SM, Carpi A, Berti P, Materazzi G, Minuto M, Guastalli M, Miccoli P. Dedifferentiated thyroid cancer a therapeutic challenge. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2008;62(8):559–563. doi: 10.1016/j.biopha.2008.07.056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Antonelli A, Bocci G, La Motta C, Ferrari SM, Fallahi P, Fioravanti A, Sartini S, Minuto M, Piaggi S, Corti A, Alì G, Berti P, Fontanini G, Danesi R, Da Settimo F, Miccoli P. Novel pyrazolopyrimidine derivatives as tyrosine kinase inhibitors with antitumoral activity in vitro and in vivo in papillary dedifferentiated thyroid cancer. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2011;96(2):E288–E296. doi: 10.1210/jc.2010-1905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Antonelli A, Bocci G, La Motta C, Ferrari SM, Fallahi P, Ruffilli I, Di Domenicantonio A, Fioravanti A, Sartini S, Minuto M, Piaggi S, Corti A, Alì G, Di Desidero T, Berti P, Fontanini G, Danesi R, Da Settimo F, Miccoli P. CLM94 a novel cyclic amide with anti-VEGFR-2 and antiangiogenic properties is active against primary anaplastic thyroid cancer in vitro and in vivo. J. Clin. Endocrinol Metab. 2012;97(4):E528–E536. doi: 10.1210/jc.2011-1987. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Antonelli A, Bocci G, Fallahi P, La Motta C, Ferrari SM, Mancusi C, Fioravanti A, Di Desidero T, Sartini S, Corti A, Piaggi S, Materazzi G, Spinelli C, Fontanini G, Danesi R, Da Settimo F, Miccoli P. CLM3, a multitarget tyrosine kinase inhibitor with antiangiogenic properties, is active against primary anaplastic thyroid cancer in vitro and in vivo. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2014;99(4):E572–81. doi: 10.1210/jc.2013-2321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Giunti S, Antonelli A, Amorosi A, Santarpia L. Cellular signaling pathway alterations and potential targeted therapies for medullary thyroid carcinoma. Int. J. Endocrinol. 2013;2013:803171. doi: 10.1155/2013/803171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Antonelli A, Fallahi P, Ferrari SM, Ruffilli I, Santini F, Minuto M, Galleri D, Miccoli P. New targeted therapies for thyroid cancer. Curr. Genomics. 2011;12(8):626–631. doi: 10.2174/138920211798120808. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wells SAJr, Santoro M. Update the status of clinical trials of kinase inhibitors in thyroid cancer. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2014;99(5):1543–55. doi: 10.1210/jc.2013-2622. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ho AL, Grewal RK, Leboeuf R, Sherman EJ, Pfister DG, Deandreis D, Pentlow KS, Zanzonico PB, Haque S, Gavane S, Ghossein RA, Ricarte-Filho JC, Domínguez JM, Shen R, Tuttle RM, Larson SM, Fagin JA. Selumetinib-enhanced radioiodine uptake in advanced thyroid cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 2013;368(7):623–632. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1209288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Placzkowski KA, Reddi HV, Grebe SK, Eberhardt NL, McIver B. The role of the PAX8/PPAgamma fusion oncogene in thyroid cancer. PPAR Res. 2008;2008:672829. doi: 10.1155/2008/672829. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Vandenberg LN, Colborn T, Hayes TB, Heindel JJ, Jacobs DRJr, Lee DH, Shioda T, Soto AM, vom Saal FS, Welshons WV, Zoeller RT, Myers JP. Hormones and endocrine-disrupting chemicals low-dose effects and nonmonotonic dose responses. Endocr. Rev. 2012;33(3):378–455. doi: 10.1210/er.2011-1050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kiang JG, Wang XD, Ding XZ, Gist ID, Smallridge RC. Heat shock inhibits the hypoxia- induced effects on iodide uptake and signal transduction and enhances cell survival in rat thyroid FRTL-5 cells. Thyroid. 1996;6(5):475–483. doi: 10.1089/thy.1996.6.475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Karbownik M, Lewinski A. The role of oxidative stress in physiological and pathological processes in the thyroid gland; possible involvement in pineal-thyroid interactions. Neuro. Endocrinol. Lett. 2003;24(5):293–303. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Xing M. Oxidative stress: a new risk factor for thyroid cancer. Endocr Rel Canc. 2012;19(1):C7–C11. doi: 10.1530/ERC-11-0360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Burrows N, Resch J, Cowen RL, von Wasielewski R, Hoang Vu C, West CM, Williams KJ, Brabant G. Expression of hypoxia-inducible factor 1 alpha in thyroid carcinomas. Endocr. Relat. Canc. 2010;17(1):61–72. doi: 10.1677/ERC-08-0251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Feng C, Gao Y, Wang C, Yu X, Zhang W, Guan H, Shan Z, Teng W. Aberrant overexpression of pyruvate kinase M2 is associated with aggressive tumor features and the BRAF mutation in papillary thyroid cancer. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2013;98(9):E1524–E1533. doi: 10.1210/jc.2012-4258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Koch CA, Sarlis NJ, Lang F, Bornstein SR, LeRoith D. Section Editors Thyroid cancer.In Encyclopedic Reference Molecular Mechanisms of Disease Endocrinology and Diabetes section (Textbook). Editor-in-Chief Springer Publisher GmbH Berlin Germany. (online and in print. Tome:LXXXVI web address: http://www.springerlink.com/content/ g7t6654638x483g8/fulltext.html. . 2009 [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kohn LD, Shimura H, Shimura Y, Hidaka A, Giuliani C, Napolitano G, Ohmori M, Laglia G, Saji M. The thyrotropin receptor. Vitam. Horm. 1995;50:287–384. doi: 10.1016/s0083-6729(08)60658-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Metaye T, Menet E, Guilhot J, Kraimps JL. Expression and activity of G protein-coupled receptor kinases in differentiated thyroid carcinoma. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2002;87(7):3279–3286. doi: 10.1210/jcem.87.7.8618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Nagayama Y, Tanaka K, Hara T, Namba H, Yamashita S, Taniyama K, Niwa M. Involvement of G protein-coupled receptor kinase-5 in homologous desensitization of the thyrotropin receptor. J. Biol. Chem. 1996;271(17):10143–10148. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.17.10143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Iacovelli L, Franchetti R, Masini M, De Blasi A. GRK2 and beta-arrestin 1 as negative regulators of thyrotropin receptor-stimulated response. Mol. Endocrinol. 1996;10(9):1138–1146. doi: 10.1210/mend.10.9.8885248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Cetani F, Tonacchera M, Pinchera A, Barsacchi R, Basolo F, Miccoli P, Pacini F. Genetic analysis of the TSH receptor gene in differentiated human thyroid carcinomas. J. Endocrinol. Invest. 1999;22(4):273–278. doi: 10.1007/BF03343556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Jaeschke H, Mueller S, Eszlinger M, Paschke R. Lack of in vitro constitutive activity for four previously reported TSH receptor mutations identified in patients with nonautoimmune hyperthyroidism and hot thyroid carcinomas. Clin. Endocrinol. (Oxf) 2010;73(6):815–820. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2265.2010.03872.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Pazaitou-Panayiotou K, Michalakis K, Paschke R. Thyroid cancer in patients with hyperthyroidism. Horm. Metab. Res. 2012;44(4):255–262. doi: 10.1055/s-0031-1299741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hepler JR. Emerging roles for RGS proteins in cell signalling. Trends. Pharmacol. Sci. 1999;20(9):376–382. doi: 10.1016/s0165-6147(99)01369-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ruggeri RM, Campennì A, Giovinazzo S, Saraceno G, Vicchio TM, Carlotta D, Cucinotta MP, Micali C, Trimarchi F, Tuccari G, Baldari S, Benvenga S. Follicular variant of papillary thyroid carcinoma presenting as toxic nodule in an adolescent: coexistent polymorphism of the TSHR and Gsa genes. Thyroid. 2013;23(2):239–242. doi: 10.1089/thy.2012.0279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Hamacher C, Studer H, Zbaeren J, Schatz H, Derwahl M. Expression of functional stimulatory guanine nucleotide binding protein in nonfunctioning thyroid adenomas is not correlated to adenylate cyclase activity and growth of these tumors. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 1995;80(5):1724–1732. doi: 10.1210/jcem.80.5.7745026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Mastorakos G, Mitsiades NS, Doufas AG, Koutras DA. Hyperthyroidism in McCune-Albright syndrome with a review of thyroid abnormalities sixty years after the ?rst report. Thyroid. 1997;7(3):433–439. doi: 10.1089/thy.1997.7.433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Collins MT, Sarlis NJ, Merino MJ, Monroe J, Crawford SE, Krakoff JA, Guthrie LC, Bonat S, Robey PG, Shenker A. Thyroid carcinoma in the McCune-Albright syndrome: contributory role of activating Gs alpha mutations. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2003;88(9):4413–4417. doi: 10.1210/jc.2002-021642. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Ekokoski E, Dugue B, Vainio M, Vainio PJ, Tornquist K. Extracellular ATP-mediated phospholipase A(2) activation in rat thyroid FRTL-5 cells: regulation by a G(i)/G(o) protein, Ca(2+): and mitogen- activated protein kinase. J. Cell. Physiol. 2000;183(2):155–162. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-4652(200005)183:2<155::AID-JCP2>3.0.CO;2-R. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Balsinde J, Winstead MV, Dennis EA. Phospholipase A(2) regulation of arachidonic acid mobilization. FEBS Lett. 2002;531(1):2–6. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(02)03413-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Mariggiò S, Filippi BM, Iurisci C, Dragani LK, De Falco V, Santoro M, Corda D. Cytosolic phospholipase A2 alpha regulates cell growth in RET/PTC-transformed thyroid cells. Cancer. Res. 2007;67(24):11769–11778. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-1997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Kummer NT, Nowickim TS, Azzi JP, Reyes I, Iacob C, Xie S, Swati I, Darzynkiewicz Z, Gotlinger KH, Suslina N, Schantz S, Tiwari RK, Geliebter J. Arachidonate 5 lipoxygenase expression in papillary thyroid carcinoma promotes invasion via MMP-9 induction. J. Cell. Biochem. 2012;113(6):1998–2008. doi: 10.1002/jcb.24069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Siironen P, Ristimäki A, Nordling S, Louhimo J, Haapiainen R, Haglund C. Expression of COX-2 is increased with age in papillary thyroid cancer. Histopathology. 2004;44(5):490–497. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2559.2004.01880. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Ringel MD, Hardy E, Bernet VJ, Burch HB, Schuppert F, Burman KD, Saji M. Metastin receptor is overexpressed in papillary thyroid cancer and activates MAP kinase in thyroid cancer cells. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2002;87(5):2399. doi: 10.1210/jcem.87.5.8626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Voigt C, Holzapfel HP, Paschke R. Decreased expression of G-protein coupled receptor kinase 2 in cold thyroid nodules. Exp. Clin. Endocrinol. Diabetes. 2005;113(2):102–106. doi: 10.1055/s-2004-830538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Kirschner LS, Carney JA, Pack SD, Taymans SE, Giatzakis C, Cho YS, Cho-Chung YS, Stratakis CA. Mutations of the gene encoding the protein kinase A type I-alpha regulatory subunit in patients with the Carney complex. Nat. Genet. 2000;26(1):89–92. doi: 10.1038/79238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Sandrini F, Matyakhina L, Sarlis NJ, Kirschner LS, Farmakidis C, Gimm O, Stratakis CA. Regulatory subunit type I-alpha of protein kinase A (PRKAR1A): a tumor-suppressor gene for sporadic thyroid cancer. Genes. Chromosomes. Canc. 2002;35(2):182–192. doi: 10.1002/gcc.10112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Rosenberg D, Groussin L, Jullian E, Perlemoine K, Bertagna X, Bertherat J. Role of the PKA- regulated transcription factor CREB in development and tumorigenesis of endocrine tissues. Ann. N Y. Acad. Sci. 2002;968:65–74. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2002.tb04327.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Cantara S, D'Angeli F, Toti P, Lignitto L, Castagna MG, Capuano S, Prabhakar BS, Feliciello A, Pacini F. Expression of the ring ligase PRAJA2 in thyroid cancer. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2012;97(11):4253–4259. doi: 10.1210/jc.2012-2360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Coppee F, Gerard AC, Denef JF, Ledent C, Vassart G, Dumont JE, Parmentier M. Early occurrence of metastatic differentiated thyroid carcinomas in transgenic mice expressing the A2a adenosine receptor gene and the human papillomavirus type 16 E7 oncogene. Oncogene. 1996;13(7):1471–1482. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Kobayashi K, Shaver JK, Liang W, Siperstein AE, Duh QY, Clark OH. Increased phospholipase C activity in neoplastic thyroid membrane. Thyroid. 1993;3(1):25–29. doi: 10.1089/thy.1993.3.25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Osborne NN, Tobin AB, Ghazi H. Role of inositol trisphosphate as a second messenger in signal transduction processes: an essay. Neurochem. Res. 1988;13(3):177–191. doi: 10.1007/BF00971531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Schlessinger J. Cell signaling by receptor tyrosine kinases. Cell. 2000;103(2):211–225. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)00114-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Xing M, Haugen BR, Schlumberger M. Progress in molecular-based management of differentiated thyroid cancer. Lancet. 2013;381(9871):1058–1069. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)60109-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Mitsiades CS, Poulaki V, Mitsiades N. The role of apoptosis-inducing receptors of the tumor necrosis factor family in thyroid cancer. J. Endocrinol. 2003;178(2):205–216. doi: 10.1677/joe.0.1780205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Malkomes P, Oppermann E, Bechstein WO, Holzer K. Vascular endothelial growth factor - marker for proliferation in thyroid diseases?. Exp. Clin. Endocrinol. Diabetes. 2013;121(1):6–13. doi: 10.1055/s-0032-1327634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Yasuoka H, Kodama R, Hirokawa M, Takamura Y, Miyauchi A, Inagaki M, Sanke T, Nakamura Y. Neuropilin-2 expression in papillary thyroid carcinoma: correlation with VEGF-D expression, lymph node metastasis, and VEGF-D-induced aggressive cancer cell phenotype. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2011;96(11):E1857–E1861. doi: 10.1210/jc.2011-1180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Fisher KE, Jani JC, Fisher SB, Foulks C, Hill CE, Weber CJ, Cohen C, Sharma J. Epidermal growth factor receptor overexpression is a marker for adverse pathologic features in papillary thyroid carcinoma. J. Surg. Res. 2013;185(1):217–224. doi: 10.1016/j.jss.2013.05.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Bruland O, Fluge Ø , Akslen LA, Eiken HG, Lillehaug JR, Varhaug JE, Knappskog PM. Inverse correlation between PDGFC expression and lymphocyte infiltration in human papillary thyroid carcinomas. BMC Canc. 2009;9:425. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-9-425. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Ruggeri RM, Villari D, Simone A, Scarfi R, Attard M, Orlandi F, Barresi G, Trimarchi F, Trovato M, Benvenga S. Co-expression of interleukin-6 (IL-6) and interleukin-6 receptor (IL-6R) in thyroid nodules is associated with co-expression of CD30 ligand/CD30 receptor. J. Endocrinol. Invest. 2002;25(11):959–966. doi: 10.1007/BF03344068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Huang BY, Hseuh C, Chao TC, Lin KJ, Lin JD. Well-differentiated thyroid carcinoma with concomitant Hashimoto's thyroiditis present with less aggressive clinical stage and low recurrence. Endocr. Pathol. 2011;22(3):144–149. doi: 10.1007/s12022-011-9164-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Antonelli A, Ferrari SM, Fallahi P, Frascerra S, Piaggi S, Gelmini S, Lupi C, Minuto M, Berti P, Benvenga S, Basolo F, Orlando C, Miccoli P. Dysregulation of secretion of CXC alpha-chemokine CXCL10 in papillary thyroid cancer: modulation by peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-gamma agonists. Endocr. Relat. Canc. 2009;16(4):1299–1311. doi: 10.1677/ERC-08-0337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Torregrossa L, Giannini R, Borrelli N, Sensi E, Melillo RM, Leocata P, Materazzi G, Miccoli P, Santoro M, Basolo F. CXCR4 expression correlates with the degree of tumor infiltration and BRAF status in papillary thyroid carcinomas. Mod. Pathol. 2012;25(1):46–55. doi: 10.1038/modpathol.2011.140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Costello A, Rey-Hipolito C, Patel A, Oakley K, Vasco V, Calabria C, Tuttle RM, Francis GL. Thyroid cancers express CD-40 and CD-40 ligand: cancers that express CD-40 ligand may have a greater risk of recurrence in young patients. Thyroid. 2005;15(2):105–113. doi: 10.1089/thy.2005.15.105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.French JD, Weber ZJ, Fretwell DL, Said S, Klopper JP, Haugen BR. Tumor-associated lymphocytes and increased FoxP3+ regulatory T cell frequency correlate with more aggressive papillary thyroid cancer. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2010;95(5):2325–2333. doi: 10.1210/jc.2009-2564. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Trovato M, Villari D, Ruggeri RM, Quattrocchi E, Fragetta F, Simone A, Scarfi R, Magro G, Batolo D, Trimarchi F, Benvenga S. Expression of CD30 ligand and CD30 receptor in normal thyroid and benign and malignant thyroid nodules. Thyroid. 2001;11(7):621–628. doi: 10.1089/105072501750362682. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Li X, Abdel-Mageed AB, Mondal D, Kandil E. The nuclear factor kappa-B signaling pathway as a therapeutic target against thyroid cancers. Thyroid. 2012; PMID:22889272. doi: 10.1089/thy.2012.0237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Romei C, Elisei R. RET/PTC Translocations and Clinico-Pathological Features in Human Papillary Thyroid Carcinoma. Front Endocrinol. (Lausanne): 2012;3:54. doi: 10.3389/fendo.2012.00054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Sugishita Y, Kammori M, Yamada O, Poon SS, Kobayashi M, Onoda N, Yamazaki K, Fukumori T, Yoshikawa K, Onose H, Ishii S, Yamada E, Yamada T. Amplification of the human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 gene in differentiated thyroid cancer correlates with telo-mere shortening. Int. J. Oncol. 2013;42(5):1589–1596. doi: 10.3892/ijo.2013.1848. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Kremser R, Obrist P, Spizzo G, Erler H, Kendler D, Kemmler G, Mikuz G, Ensinger C. Her2/neu overexpression in differentiated thyroid carcinomas predicts metastatic disease. Virchows Arch. 2003;442(4):322–328. doi: 10.1007/s00428-003-0769-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Trovato M, Villari D, Bartolone L, Spinella S, Simone A, Violi MA, Trimarchi F, Batolo D, Benvenga S. Expression of the hepatocyte growth factor and c-met in normal thyroid, non-neoplastic, and neoplastic nodules. Thyroid. 1998;8(2):125–131. doi: 10.1089/thy.1998.8.125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Ruggeri RM, Vitarelli E, Barresi G, Trimarchi F, Benvenga S, Trovato M. HGF/C-MET system pathways in benign and malignant histotypes of thyroid nodules: an immunohistochemical characterization. Histol. Histopathol. 2012;27(1):113–121. doi: 10.14670/HH-27.113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Siraj AK, Bavi P, Abubaker J, Jehan Z, Sultana M, Al-Dayel F, Al-Nuaim A, Alzahrani A, Ahmed M, Al-Sanea O, Uddin S, Al-Kuraya KS. Genome-wide expression analysis of Middle Eastern papillary thyroid cancer reveals c-MET as a novel target for cancer therapy. J. Pathol. 2007;213(2):190–199. doi: 10.1002/path.2215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Volante M, Rapa I, Gandhi M, Bussolati G, Giachino D, Papotti M, Nikiforov YE. RAS mutations are the predominant molecular alteration in poorly differentiated thyroid carcinomas and bear prognostic impact. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2009;94(12):4735–4741. doi: 10.1210/jc.2009-1233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Dent P, Yacoub A, Contessa J, Caron R, Amorino G, Valerie K, Hagan MP, Grant S, Schmidt- Ullrich R. Stress and radiation-induced activation of multiple intracellular signaling pathways. Radiat. Res. 2003;159(3):283–300. doi: 10.1667/0033-7587(2003)159[0283:sariao]2.0.co;2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Kumar S, Boehm J, Lee JC. p38 MAP kinases: key signalling molecules as therapeutic targets for in?ammatory diseases. Nat. Rev. Drug. Discov. 2003;2(9):717–726. doi: 10.1038/nrd1177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Guerra A, Sapio MR, Marotta V, Campanile E, Rossi S, Forno I, Fugazzola L, Budillon A, Moccia T, Fenzi G, Vitale M. The primary occurrence of BRAF(V600E) is a rare clonal event in papillary thyroid carcinoma. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2012;97(2):517–524. doi: 10.1210/jc.2011-0618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Walczyk A, Kowalska A, Kowalik A, Sygut J, Wypiórkiewicz E, Chodurska R, Pieciak L, Gózdz S. The BRAFV 600E Mutation in Papillary Thyroid Microcarcinoma: Does the Mutation have an Impact on Clinical Outcome?. Clin. Endocrinol. (Oxf) 2013;80(6):899–904. doi: 10.1111/cen.12386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Li C, Aragon Han P, Lee KC, Lee LC, Fox AC, Beninato T, Thiess M, Dy BM, Sebo TJ, Thompson GB, Grant CS, Giordano TJ, Gauger PG, Doherty GM, Fahey TJ 3r. Does BRAF V600E mutation predict aggressive features in papillary thyroid cancer?. Results from four endocrine surgery centers. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2013;98(9):3702–3712. doi: 10.1210/jc.2013-1584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Sarlis NJ. Expression patterns of cellular growth-controlling genes in non-medullary thyroid cancer: basic aspects. Rev. Endocr. Metab. Disord. 2000;1(3):183–196. doi: 10.1023/a:1010079031162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Orloff MS, He X, Peterson C, Chen F, Chen JL, Mester JL, Eng C. Germline PIK3CA and AKT1 mutations in Cowden and Cowden-like syndromes. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2013;92(1):76–80. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2012.10.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Xing M. Genetic alterations in the phosphatidylinositol-3 kinase/Akt pathway in thyroid cancer. Thyroid. 2010;20(7):697–706. doi: 10.1089/thy.2010.1646. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Kouvaraki MA, Liakou C, Paraschi A, Dimas K, Patsouris E, Tseleni-Balafouta S, Rassidakis GZ, Moraitis D. Activation of mTOR signaling in medullary and aggressive papillary thyroid carcinomas. Surgery. 2011;150(6):1258–1265. doi: 10.1016/j.surg.2011.09.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Newman BD, Maher JF, Subauste JS, Uwaifo GI, Bigler SA, Koch CA. Clustering of sebaceous gland carcinoma, papillary thyroid carcinoma and breast cancer in a woman as a new cancer susceptibility disorder: a case report. J. Med. Case. Rep. 2009;3:6905. doi: 10.4076/1752-1947-3-6905. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Koch CA, Brouwers FM, Vortmeyer AO, Tannapfel A, Libutti SK, Zhuang Z, Pacak K, Neumann HP, Paschke R. Somatic VHL gene alterations in MEN2-associated medullary thyroid carcinoma. BMC Canc. 2006;6:131. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-6-131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Trovato M, Grosso M, Vitarelli E, Ruggeri RM, Alesci S, Trimarchi F, Barresi G, Benvenga S. Distinctive expression of STAT3 in papillary thyroid carcinomas and a subset of follicular adenomas. Histol. Histopathol. 2003;18(2):393–399. doi: 10.14670/HH-18.393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Mishunina TM, Kalinichenko OV, Tronko MD, Statsenko OA. Caspase-3 activity in papillary thyroid carcinomas. Exp. Oncol. 2010;32(4):269–272. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Fisher DE. Pathways of apoptosis and the modulation of cell death in cancer. Hematol. Oncol. Clin. North. Am. 2001;15(5):931–956. doi: 10.1016/s0889-8588(05)70258-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Koch CA, Vortmeyer AO, Diallo R, Poremba C, Giordano TJ, Sanders D, Bornstein SR, Chrousos GP, Pacak K. Survivin: a novel neuroendocrine marker for pheochromocytoma. Eur. J. Endocrinol. 2002;146(3):381–388. doi: 10.1530/eje.0.1460381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Pannone G, Santoro A, Pasquali D, Zamparese R, Mattoni M, Russo G, Landriscina M, Piscazzi A, Toti P, Cignarelli M, Muzio LL, Bufo P. The Role of Survivin in Thyroid Tumors: Differences of Expression in Well-Differentiated, Non-Well-Differentiated, and Anaplastic Thy-roid Cancers. Thyroid. 2013 doi: 10.1089/thy.2013.0196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Ogasawara J, Watanabe-Fukunaga R, Adachi M, Matsuzawa A, Kasugai T, Kitamura Y, Itoh N, Suda T, Nagata S. Lethal effect of the anti-Fas antibody in mice. Nature. 1993;364(6440):806–809. doi: 10.1038/364806a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Shi Y, Massague J. Mechanisms of TGF-beta signaling from cell membrane to the nucleus. Cell. 2003;113(6):685–700. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(03)00432-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Schulte KM, Jonas C, Krebs R, Roher HD. Activin A and activin receptors in thyroid cancer. Thyroid. 2001;11(1):3–14. doi: 10.1089/10507250150500603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Bravo SB, Pampin S, Cameselle-Teijeiro J, Carneiro C, Dominguez F, Barreiro F, Alvarez CV. TGF-beta-induced apoptosis in human thyrocytes is mediated by p27kip1 reduction and is overridden in neoplastic thyrocytes by NF-kappaB activation. Oncogene. 2003;22(49):7819–7830. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1207029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Pesutic-Pisac V, Punda A, Gluncic I, Bedekovic V, Pranic-Kragic A, Kunac N. Cyclin D1 and p27 expression as prognostic factor in papillary carcinoma of thyroid association with clinicopathological parameters. Croat Med J. 2008;49(5):643–649. doi: 10.3325/cmj.2008.5.643. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Cheng S, Serra S, Mercado M, Ezzat S, Asa SL. A high-throughput proteomic approach provides distinct signatures for thyroid cancer behavior. Clin. Cancer. Res. 2011;17(8):2385–2394. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-10-2837. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Zhou YL, Liu C, Dai XX, Zhang XH, Wang OC. Overexpression of miR-221 is associated with aggressive clinicopathologic characteristics and the BRAF mutation in papillary thyroid carcinomas. Med. Oncol. 2012;29(5):3360–3366. doi: 10.1007/s12032-012-0315-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Yang Z, Yuan Z, Fan Y, Deng X, Zheng Q. Integrated analyses of microRNA and mRNA expression profiles in aggressive papillary thyroid carcinoma. Mol. Med. Rep. 2013;8(5):1353–1358. doi: 10.3892/mmr.2013.1699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Ferraz C, Lorenz S, Wojtas B, Bornstein SR, Paschke R, Eszlinger M. Inverse correlation of miRNA and cell cycle-associated genes suggests influence of miRNA on benign thyroid nodule tumorigenesis. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2013;98(1):E8–E16. doi: 10.1210/jc.2012-2564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Shen CT, Qiu Z, Luo QY. Sorafenib in radioiodine-refractory differentiated thyroid cancer: a meta-analysis. Endocr. Rel. Canc. 2013;21(2):253–61. doi: 10.1530/ERC-13-0438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Chen L, Shen Y, Luo Q, Yu Y, Lu H, Zhu R. Response to sorafenib at a low dose in patients with radioiodine-refractory pulmonary metastases from papillary thyroid carcinoma. Thyroid. 2011;21(2):119–124. doi: 10.1089/thy.2010.0199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Haugen BR, Sherman SI. Evolving approaches to patients with advanced differentiated thyroid cancer. Endocr. Rev. 2013;34:439–455. doi: 10.1210/er.2012-1038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Koch CA. Molecular pathogenesis of MEN2-associated tumors. Fam. Canc. 2005;4(1):3–7. doi: 10.1007/s10689-004-7022-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Brauer VF, Scholz GH, Neumann S, Lohmann T, Paschke R, Koch CA. RET germline mutation in codon 791 in a family representing 3 generations from age 5 to age 70 years: should thyroidectomy be performed?. Endocr. Pract. 2004;10(1):5–9. doi: 10.4158/EP.10.1.5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]