Abstract

Objectives:

To assess the impact of spatial resolution and cone beam CT (CBCT) unit on CBCT images for the detection accuracy of condylar defects.

Methods:

42 temporomandibular joints were scanned, respectively, with the CBCT units ProMax® 3D (Planmeca Oy, Helsinki, Finland) and DCT PRO (Vatech, Co., Ltd., Yongin-Si, Republic of Korea) at normal and high resolutions. Seven dentists evaluated all the test images with respect to the presence or the absence of condylar defects. Receiver operating characteristic curve analysis was employed to define the detection accuracy. Two-way analysis of variance was used to analyse the values under the receiver operating characteristic curves for the differences among imaging groups and observers. Intraobserver variation was analysed using the Wilcoxon test.

Results:

Macroscopic anatomy examination revealed that, of the 42 temporomandibular joint condylar surfaces, 18 were normal and 24 had defects on the surface of condyles. No significant differences were found between the images scanned with normal and high resolutions for both CBCT units ProMax 3D (p = 0.119) and DCT PRO (p = 0.740). Significant differences exist between image groups of DCT PRO and ProMax 3D (p < 0.05). Neither the inter- nor the intraobserver variability were significant.

Conclusions:

The spatial resolution per se did not have an impact on the detection accuracy of condylar defects. The detection accuracy of condylar defects highly depends on the CBCT unit used for examination.

Keywords: temporomandibular joint, mandibular condyle, cone-beam computed tomography

Introduction

Radiographic examination is an essential method for the evaluation of osseous abnormalities of the temporomandibular joint (TMJ). Currently, the modalities used for the evaluation of TMJ bony changes include plain radiography, CT, MRI and the recently developed cone beam CT (CBCT). As with CT and MRI, CBCT provides multiplanar and 3-dimensional (3D) images to facilitate analysis and diagnosis of bone morphological features of the mandibular condyle, joint space and dynamic function.1 Recent studies have revealed that CBCT is a reliable alternative to multislice CT for the assessment of TMJ space and osseous changes.2,3

Nowadays, CBCT scanners are available that can give users a choice between high and low spatial resolution settings when scanning a patient. In theory, the higher the number of the spatial resolution used for scanning, the smaller the radiographic details can be observed in the resultant images. This is confirmed by the study that is with respect to the detection of transverse root fractures. In this in vitro study, the CBCT images scanned with a high spatial resolution is superior to the images scanned with a low spatial resolution.4 However, another study indicates that the use of high spatial resolution mode for a CBCT scan does not increase the visibility of the root canal space when compared with the images scanned with a standard mode.5 These inconsistent results demonstrate the necessity of evaluation of various clinical tasks for CBCT images scanned at different spatial resolutions. In the search of literature, we did not find one study exclusively evaluating the impact of spatial resolution on CBCT image for the detection of condylar defects. Therefore, the aim of the present study was to assess whether spatial resolutions have an impact on the detection accuracy of condylar defects in CBCT images. Furthermore, the impact of a CBCT unit on the detection of condylar defects was investigated.

Methods and materials

Skulls and reference standard

The sample consisted of 42 TMJs obtained from 21 dry human skulls. The skulls were not identified by age, sex or ethnicity, and no demographic data were available on them. The selection criteria were depicted in a previous study.6 Owing to the use of dry human skulls in the study, the ethical approval by an institutional review board was not necessary.

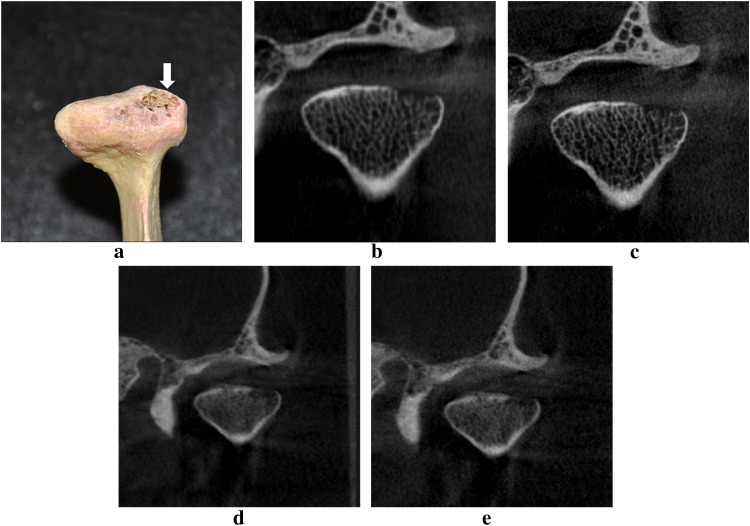

The appearances of the condylar surfaces ranged from normal to those with defects of varying sizes. The macroscopic definition of the bone defect in the present study was (1) destructive and erosive osseous changes of the condyle; (2) flattening of the articular surface of the condyle; (3) deformity of the condyle, which is a condition after a severe condylar defect. To determine the presence or the absence of bone defects, all condyles were viewed by two investigators. The following 2-point scale was used to score the status of the condylar surfaces: 0 = the absence of bone defect; 1 = at least one bone defect present on the condylar surface. In cases where the investigators' ratings diverged, a joint assessment was performed until consensus was reached. One example image of a condyle is shown in Figure 1a.

Figure 1.

(a) An example photograph of condylar defect (solid white arrow). (b) The example of cone beam CT images acquired with ProMax® 3D at normal resolution, (c) ProMax 3D at high resolution, (d) DCT PRO at normal resolution, (e) DCT PRO at high resolution of the same condylar defect. ProMax 3D was obtained from Planmeca Oy, Helsinki, Finland and DCT PRO from Vatech, Co., Ltd., Yongin-Si, Republic of Korea.

To simulate the TMJ interarticular space and to separate the mandibular condyle from the temporal fossa, an autopolymerizing acrylic resin (Meliodent; Heraeus Kulzer, Hanau, Germany) was put into both the glenoid fossas of one skull along with the associated mandible positioned to achieve its centric occlusion until the acrylic resin became rigid. For all images, the teeth were placed in centric occlusion (maximum intercuspation), and the jaws were held closed with adhesive tape.

To provide some soft-tissue attenuation, a 20-mm-thick water phantom was placed around the skull during CBCT scans.6

Cone beam CT images

CBCT images of the 42 TMJs were acquired using 2 CBCT scanners: ProMax® 3D (Planmeca Oy, Helsinki, Finland) and DCT PRO (Vatech, Co., Ltd., Yongin-Si, Republic of Korea). Both scanners use the complementary metal-oxide semiconductor flat panel detector and provide selections of normal or high spatial resolution for scanning. According to the selected spatial resolution, CBCT images were categorized into four groups: (1) ProMax 3D normal-resolution images, (2) ProMax 3D high-resolution images, (3) DCT PRO normal-resolution images and (4) DCT PRO high-resolution images. The exposure parameters for each scanning in this study are presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Specifications of the employed imaging systems for images

| Imaging system | Kv | mA | Exposure time (s) | Detector | Field of view (mm) | Voxel size (mm) | Slice thickness (mm) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ProMax® 3D | |||||||

| Normal resolution | 84 | 12 | 12 | CMOS | 80 × 80 | 0.32 | 0.96 |

| High resolution | 84 | 12 | 12 | CMOS | 80 × 80 | 0.16 | 0.48 |

| DCT PRO | |||||||

| Normal resolution | 85 | 6 | 15 | CMOS | 160 × 70 | 0.30 | 1.00 |

| High resolution | 85 | 6 | 24 | CMOS | 160 × 70 | 0.20 | 1.00 |

CMOS, complementary metal-oxide semiconductor.

ProMax® 3D was obtained from Planmeca Oy, Helsinki, Finland and DCT PRO from Vatech, Co., Ltd., Yongin-Si, Republic of Korea.

Viewing

All test images were displayed on a 22-inch Dell™ E228WFP flat panel monitor (Dell, Round Rock, TX) with a resolution of 1680 × 1050 pixels. Seven dentists who had graduated from a dental school within 5 years viewed all the images in a random order. Before viewing, the observers were provided with the information on the use of CBCT proprietary software and on the definition of radiological TMJ condylar defect. Images were displayed using the proprietary software (ProMax 3D: Romexis™ v. 2.3.0.R; Planmeca Oy and DCT PRO: Ez3D2009; Vatech, Co., Ltd.) in axial, coronal and sagittal planes, and the observers were allowed to adjust the brightness and contrast at will (Figure 1b–e). The radiological definitions of TMJ condylar defects were referred to as (1) faceting—a small, smooth, flat surface or irregularity seen on the bony outline of the condyle, producing a sharp deviation in the condylar form; (2) lack of cortical definition—the loss of peripheral opaque rim of the cortical bone; or (3) both faceting and lack of cortical contour.7 These definitions were only used when determining the presence or the absence of radiological condylar bone defects and not for the categorized statistical analysis. The observers used the following 5-point rank scale to record their level of confidence regarding the presence or the absence of condylar bone defects: 1 = definitely not present; 2 = probably not present; 3 = uncertain if present; 4 = probably present; 5 = definitely present. Viewing was conducted in a quiet room with dim lighting. Each observer evaluated only one group of test images at a time. There was at least a 1-week interval between the adjacent evaluations of two groups. To investigate the intraobserver agreement, each observer reassessed a part of the images 2 weeks later.

Data analyses

With the anatomy examination as reference standard, each observer's performance was converted into a receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve using SPSS® v.16.0 for Windows (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL). The maximum likelihood parameters were determined, and the areas under the ROC curves (AZ values) were calculated. Two-way analysis of variance was used to analyse the AZ values for the differences among imaging groups and observers. Intraobserver variation was analysed using the Wilcoxon test. Differences were considered to be statistically significant when p < 0.05.

Results

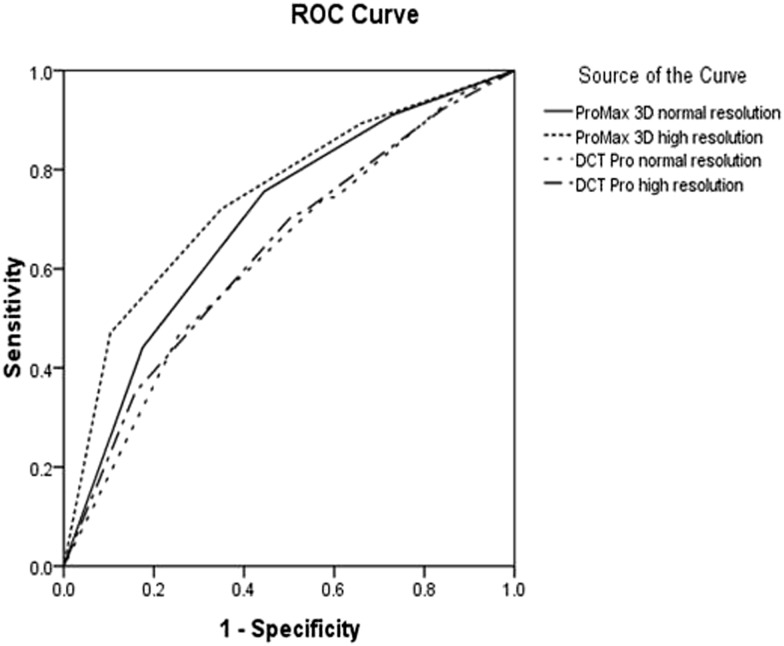

Macroscopic anatomy examination revealed that, of the 42 TMJ condylar surfaces, 18 (42.86%) were normal, whereas 24 (57.14%) had defects. Thus, 24 condylar surfaces (57.14%) were considered to be positive for defects when performing the ROC analysis. Table 2 contains the individual and mean AZ values. The p-values for multiple comparisons of observer performance from each group are presented in Table 3. Multiple comparisons of observer performances revealed that there were no significant differences between the normal- and high-resolution images of ProMax 3D. Similarly, there were no significant differences between the two image groups obtained using the DCT PRO CBCT system either. By contrast, significant differences were found between groups of DCT PRO and ProMax 3D images (Table 3). Figure 2 shows the ROC curves from the pooled observer performances. There were no significant differences between the observers (interobserver, p = 0.636) and within the observers (intraobserver, p = 0.071–0.945).

Table 2.

Area under the receiver operating characteristic curve (AZ) obtained from each observer

| Observer | ProMax® 3D |

DCT PRO |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Normal resolution | High resolution | Normal resolution | High resolution | |

| 1 | 0.712 | 0.816 | 0.648 | 0.648 |

| 2 | 0.674 | 0.723 | 0.560 | 0.686 |

| 3 | 0.743 | 0.698 | 0.641 | 0.601 |

| 4 | 0.669 | 0.766 | 0.644 | 0.685 |

| 5 | 0.667 | 0.763 | 0.671 | 0.530 |

| 6 | 0.733 | 0.743 | 0.600 | 0.627 |

| 7 | 0.720 | 0.696 | 0.632 | 0.678 |

| Mean | 0.703 | 0.744 | 0.628 | 0.636 |

| SD | 0.032 | 0.042 | 0.036 | 0.056 |

ProMax® 3D was obtained from Planmeca Oy, Helsinki, Finland and DCT PRO from Vatech, Co., Ltd., Yongin-Si, Republic of Korea.

Table 3.

p-values when comparing observer performance of each CBCT image group

| CBCT image group | ProMax® 3D |

DCT PRO |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Normal resolution | High resolution | Normal resolution | High resolution | |

| ProMax 3D high resolution | 0.119 | – | – | – |

| DCT PRO normal resolution | 0.012a | 0.000a | – | – |

| DCT PRO high resolution | 0.024a | 0.000a | 0.740 | – |

ProMax® 3D was obtained from Planmeca Oy, Helsinki, Finland and DCT PRO from Vatech, Co., Ltd., Yongin-Si, Republic of Korea.

p < 0.05, significant difference.

Figure 2.

Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve from the pooled observer performances for each imaging group when the condylar defect was detected. ProMax® 3D was obtained from Planmeca Oy, Helsinki, Finland and DCT PRO from Vatech, Co., Ltd., Yongin-Si, Republic of Korea.

Discussion

Spatial resolution is considered to be an indicator of image quality. To comply with the requirement of high image quality in clinics, many CBCT units provide selections of high or normal spatial resolutions when scanning a CBCT image. However, image quality of CBCT images is not only determined by the selected spatial resolution used for the scan but also by many other factors such as detector type, field of view (FOV), tube voltage (kVp), etc.8,9 To exclusively investigate the impact of spatial resolution on image quality, the present study was conducted. In the study, two commonly used CBCT units were used, and the FOV, tube current and tube voltage of the units were strictly defined. The results from the present study demonstrate that, within one CBCT imaging system, the CBCT images scanned at a high spatial resolution were not superior to the images scanned with a normal spatial resolution when the condylar defects were observed. This result indicates that the spatial resolution defined by the same CBCT system has no impact on the detection of condylar defects in the resultant CBCT images. This is in line with a previous study regarding the visibility of root canal space. In that study, a cadaver mandible was, respectively, scanned at a standard- and high-resolution mode of the Accuitomo 170 CBCT system (J Morita USA, Irvine, CA), and the results showed that the standard scan mode did not have a negative influence.5 In another study, the detection accuracy of condylar erosions was assessed with CBCT images scanned using different voxel sizes and FOVs. The results showed that, for assessment of bony erosions, the CBCT images acquired with a 6-inch FOV at 0.2-mm voxel size were significantly better than the images acquired with a 12-inch FOV at 0.4-mm voxel size in the CB MercuRay™ (Hitachi Medical, Twinsburgh, OH) CBCT system.10 The referenced study discloses the combined effects of FOV and voxel sizes but does not further disclose the effect of voxel size solely on the detection of condylar erosions.

Another finding of the present study was that the detection accuracy of condylar defects was closely related to the imaging system used for acquiring CBCT images. For the ProMax 3D, the AZ values that is a representative of detection accuracy were 0.703 and 0.744 for normal- and high-resolution group images, respectively, whereas for the DCT PRO, the corresponding AZ values were 0.628 and 0.636. The differences were statistically significant. This is in agreement with a study in which six different CBCT imaging systems were employed for the determination of external root absorption.11 CBCT systems were also found to be varied in the determination of image quality and visualization of anatomical structures.12,13

A limitation of the present study was that only condylar defects were assessed. These defects naturally occurred or were induced during use. We did not evaluate other bone changes of TMJ disorders such as flattening or osteophytes owing to the small number of these osseous abnormalities.

In conclusion, CBCT images scanned with a high spatial resolution were not superior to the images scanned with a normal spatial resolution in terms of detection of condylar defects. Since radiation dose is increased with an increased spatial resolution,14,15 it is suggested that normal resolution, which gives a lower radiation dose, should be used for the evaluation of condylar defects when necessary. The detection accuracy of condylar defects highly depends on the CBCT unit used for examination.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to express their sincere appreciations to all the observers who assessed the test images.

References

- 1.Scarfe WC. Farman AG cone-beam computed tomography. In: White SC, Pharoah MJ, eds. Oral radiology: principle and interpretation. 6th edn. Maryland Heights, MO: Mosby Inc.; 2009. pp. 225–43. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zain-Alabdeen EH, Alsadhan RI. A comparative study of accuracy of detection of surface osseous changes in the temporomandibular joint using multidetector CT and cone beam CT. Dentomaxillofac Radiol 2012; 41: 185–91. doi: 10.1259/dmfr/24985981 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Katakami K, Shimoda S, Kobayashi K, Kawasaki K. Histological investigation of osseous changes of mandibular condyles with backscattered electron images. Dentomaxillofac Radiol 2008; 37: 330–9. doi: 10.1259/dmfr/93169617 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wenzel A, Haiter-Neto F, Frydenberg M, Kirkevang LL. Variable-resolution cone-beam computerized tomography with enhancement filtration compared with intraoral photostimulable phosphor radiography in detection of transverse root fractures in an in vitro model. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod 2009; 108: 939–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hassan BA, Payam J, Juyanda B, van der Stelt P, Wesselink PR. Influence of scan setting selections on root canal visibility with cone beam CT. Dentomaxillofac Radiol 2012; 41: 645–8. doi: 10.1259/dmfr/27670911 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zhang ZL, Li G, Zhang JZ, Zhang ZY, Ma XC. Measurement accuracy of temporomandibular joint space in Promax 3-dimensional cone-beam computerized tomography images. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol 2012; 114: 112–17. doi: 10.1016/j.oooo.2011.11.020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Honey OB, Scarfe WC, Hilgers MJ, Klueber K, Silveira AM, Haskell BS, et al. Accuracy of cone-beam computed tomography imaging of the temporomandibular joint: comparisons with panoramic radiology and linear tomography. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop 2007; 132: 429–38. doi: 10.1016/j.ajodo.2005.10.032 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Baba R, Ueda K, Okabe M. Using a flat-panel detector in high resolution cone beam CT for dental imaging. Dentomaxillofac Radiol 2004; 33: 285–90. doi: 10.1259/dmfr/87440549 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bechara B, McMahan CA, Moore WS, Noujeim M, Geha H. Contrast-to-noise ratio with different large volumes in a cone-beam computerized tomography machine: an in vitro study. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol 2012; 114: 658–65. doi: 10.1016/j.oooo.2012.08.436 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Librizzi ZT, Tadinada AS, Valiyaparambil JV, Lurie AG, Mallya SM. Cone-beam computed tomography to detect erosions of the temporomandibular joint: effect of field of view and voxel size on diagnostic efficacy and effective dose. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop 2011; 140: e25–30. doi: 10.1016/j.ajodo.2011.03.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Alqerban A, Jacobs R, Fieuws S, Nackaerts O, Willems G. Comparison of 6 cone-beam computed tomography systems for image quality and detection of simulated canine impaction-induced external root resorption in maxillary lateral incisors. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop 2011; 140: e129–39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Liang X, Jacobs R, Hassan B, Li L, Pauwels R, Corpas L, et al. A comparative evaluation of cone beam computed tomography (CBCT) and multi-slice CT (MSCT) part I. On subjective image quality. Eur J Radiol 2010; 75: 265–9. doi: 10.1016/j.ejrad.2009.03.042 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Loubele M, Maes F, Jacobs R, van Steenberghe D, White SC, Suetens P. Comparative study of image quality for MSCT and CBCT scanners for dentomaxillofacial radiology applications. Radiat Prot Dosimetry 2008; 129: 222–6. doi: 10.1093/rpd/ncn154 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Qu XM, Li G, Ludlow JB, Zhang ZY, Ma XC. Effective radiation dose of ProMax 3D cone-beam computerized tomography scanner with different dental protocols. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod 2010; 110: 770–6. doi: 10.1016/j.tripleo.2010.06.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pauwels R, Beinsberger J, Collaert B, Theodorakou C, Rogers J, Walker A, et al. Effective dose range for dental cone beam computed tomography scanners. Eur J Radiol 2012; 81: 267–71. doi: 10.1016/j.ejrad.2010.11.028 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]