Abstract

Objective: The purpose of this study was to assess the effect of guanfacine extended release (GXR) adjunctive to a psychostimulant on oppositional symptoms in children and adolescents with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD).

Methods: A multicenter, double-blind, placebo-controlled dose-optimization study of GXR (1-4 mg/d) or placebo administered morning (a.m.) or evening (p.m.) adjunctive to psychostimulant was conducted in subjects ages 6–17 with suboptimal response to psychostimulant alone. Suboptimal response was defined as treatment with a stable dose of psychostimulant for ≥4 weeks with ADHD Rating Scale IV total score ≥24 and Clinical Global Impressions-Severity of Illness score ≥3, as well as investigator opinion. Primary efficacy and safety results have been reported previously. Secondary efficacy measures included the oppositional subscale of the Conners' Parent Rating Scale–Revised: Long Form (CPRS–R:L); these are reported herein.

Results: Significant reductions from baseline to the final on-treatment assessment on the oppositional subscale of the CPRS–R:L were seen with GXR plus psychostimulant compared with placebo plus psychostimulant, both in the overall study population (placebo-adjusted least squares [LS] mean change from baseline to the final on-treatment assessment: GXR a.m.+psychostimulant, −2.4, p=0.001; GXR p.m.+psychostimulant, −2.2, p=0.003) as well as in the subgroup of subjects with significant baseline oppositional symptoms (GXR a.m.+psychostimulant, −3.6, p=0.001; GXR p.m.+psychostimulant, −2.7, p=0.013). Treatment-emergent adverse events were reported by 77.3%, 76.3%, and 63.4% of subjects in the GXR a.m., GXR p.m., and placebo groups, respectively, in the overall study population.

Conclusions: GXR adjunctive to a psychostimulant significantly reduced oppositional symptoms compared with placebo plus a psychostimulant in subjects with ADHD and a suboptimal response to psychostimulant alone.

Introduction

Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) affects an estimated 7.2% of children and adolescents 4–17 years of age in the United States (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention 2010). In 30–60% of children and adolescents with ADHD, the core symptoms of inattention and hyperactivity/impulsivity are accompanied by oppositional symptoms such as anger, hostility, irritability, arguing, and refusing to comply with rules set by adults (Biederman et al. 2007; Connor et al. 2010). The presence of comorbid oppositional symptoms in patients with ADHD has been associated with greater impairment of academic and social functioning Harpold et al. 2007; Steiner and Remsing 2007; (Connor and Doerfler 2008).

Although psychostimulants are considered first-line pharmacotherapy for ADHD, up to 25–30% of patients do not experience adequate response to psychostimulant monotherapy (Cantwell 1996; Scahill et al. 2001; Pliszka et al. 2006). Guanfacine extended release (GXR) is a selective α2A-adrenoceptor agonist, is approved by the United States Food and Drug Administration, both as monotherapy and as adjunctive therapy to psychostimulant medication, for the treatment of ADHD in children and adolescents ages 6–17 years (INTUNIV 2011). The efficacy and safety of GXR as monotherapy for the treatment of ADHD in children and adolescents ages 6–17 years have been demonstrated in two large, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, short-term pivotal trials (Biederman et al. 2008; Sallee et al. 2009b).

A more recent double-blind, placebo-controlled monotherapy study examined treatment with GXR in children with ADHD and the presence of significant oppositional symptoms (Connor et al. 2010). In this study, the presence of significant oppositional symptoms was defined as a baseline Conners' Parent Rating Scale–Revised: Long Form (CPRS–R:L) oppositional subscale score ≥14 (for boys) or ≥12 (for girls). Statistically significant reductions in oppositional symptoms, as measured by CPRS–R:L oppositional subscale scores, were observed with GXR monotherapy compared with placebo (p<0.001; effect size=0.59). Significant reductions in the core symptoms of ADHD as measured by the ADHD Rating Scale IV (ADHD-RS-IV) were also observed with GXR monotherapy compared with placebo (p<0.001; effect size=0.92) (Connor et al. 2010).

GXR adjunctive to a psychostimulant was initially studied in an open-label study (n=75) that continued into a 2-year safety study in children and adolescents with ADHD who had a suboptimal response to a psychostimulant alone (Sallee et al. 2009a; Spencer et al. 2009). This pilot study supported the use of GXR adjunctive to a psychostimulant with improvements seen from baseline to end-point in ADHD-RS-IV total scores. No unique adverse events (AEs) were observed with GXR adjunctive to a psychostimulant compared with those observed historically with either treatment alone (Sallee et al. 2009a; Spencer et al. 2009).

Subsequently, a randomized double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of GXR adjunctive to a psychostimulant in subjects with suboptimal response to a psychostimulant alone was conducted. The primary efficacy and safety results have been reported previously (Wilens et al. 2012). In this study, adjunctive administration of GXR was associated with reductions in core ADHD symptoms based on the primary efficacy instrument, the ADHD-RS-IV, and was not associated with unique AEs compared with those reported historically with either treatment alone. The objective of this current analysis was to examine the effect of GXR adjunctive to a psychostimulant on comorbid oppositional symptoms based on a secondary efficacy measure, the oppositional subscale of the CPRS–R:L in the overall study population and in a subgroup of subjects presenting with significant oppositional symptoms at baseline.

Methods

Subjects

Children and adolescents 6–17 years of age with a primary diagnosis of ADHD, any subtype, based on a detailed psychiatric evaluation using the Kiddie-Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia–Present and Lifetime version (K-SADS-PL) were enrolled in this study. Subjects were required to have exhibited partial but suboptimal response to treatment with a long-acting oral psychostimulant for ≥4 weeks prior to screening. A suboptimal response was to be documented at least 14 days before the baseline visit and confirmed at the baseline visit. Suboptimal response was defined as treatment with a stable dose of psychostimulant for ≥4 weeks with improvement in, yet persistence of, mild to moderate ADHD symptoms (defined as an ADHD-RS-IV total score ≥24 and Clinical Global Impressions-Severity of Illness score ≥3), as well as investigator judgment.

Key exclusion criteria for the study included absence of response to subject's current psychostimulant; a current, controlled or uncontrolled comorbid psychiatric diagnosis (except oppositional defiant disorder [ODD]), including any severe comorbid Axis II disorders or severe Axis I disorders; or a history or presence of cardiac abnormality. Oppositional symptoms at baseline were not required for study entry.

A participating subject's parent or legally authorized representative provided written informed consent, and the subject provided assent as required per local regulation, prior to any study-specific procedures being performed. The study protocol and final informed/assent documents were approved by an institutional review board, and the study was conducted in accordance with the principles outlined in the International Conference on Harmonisation of Good Clinical Practice and the Declaration of Helsinki.

Study design

This was a 9-week, randomized, double-blind, multicenter, placebo-controlled dose-optimization study. The 9-week treatment period included dose optimization (5 weeks), dose maintenance (3 weeks), and dose tapering (1 week). Subjects continued taking their stable morning psychostimulant dose in addition to morning (a.m.) or evening (p.m.) doses of GXR or placebo. At baseline (visit 2), subjects were randomized in a 1:1:1 ratio to receive GXR on awakening and placebo at bedtime (GXR a.m.), placebo on awakening and GXR at bedtime (GXR p.m.), or placebo on both awakening and at bedtime in addition to their current stable dose of stimulant. Visits were scheduled 7 (±2) days apart during the 5 week dose-optimization period and the 3 week dose-maintenance period. Visit 10 (week 8) was the scheduled final on-treatment assessment for efficacy for the study.

During dose optimization, GXR was initiated at a dose of 1 mg/day and titrated in 1-mg/week increments (up to 4 mg/day) to the optimal dose, defined as a clinically significant reduction in ADHD symptoms with minimal side effects. The determination of optimal dose was based on investigators' evaluation of overall clinical condition, efficacy, and safety.

During dose maintenance, subjects were maintained at their optimal dose of GXR. A single 1 mg/day dose reduction was permitted during the study at any time to ensure the subject's safety. Subjects were maintained on their stable dose of psychostimulant throughout the study.

Efficacy assessments

The oppositional subscale of the CPRS–R:L was a secondary efficacy measure; primary efficacy results from the ADHD-RS-IV have been previously published (Wilens et al. 2012). The CPRS–R:L is an 80 item rating scale designed to evaluate problem behaviors, ADHD, and comorbid disorders, based on Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 4th ed. (DSM-IV) symptomatology (American Psychiatric Association 1994). In this study, the oppositional subscale of the CPRS–R:L was administered alone (without the other subscales of the CPRS–R:L). The oppositional subscale contains 10 items designed to reflect DSM-IV criteria for ODD. Each item is scored using a range from 0 (not true at all [never, seldom]) to 3 (very much true [very often, very frequent]). The oppositional subscale of the CPRS–R:L was administered to all subjects at screening, baseline, week 8/early termination (visit 10), and at week 9/last dose on taper (visit 11). The subgroup of subjects with CPRS–R:L oppositional subscale scores ≥1.5 standard deviations (SDs) from age- and sex-normative values were defined a priori (prior to database lock and unblinding) as having significant oppositional symptoms at baseline (Conners 1997). A post-hoc analysis was conducted comparing those with and without a diagnosis of ODD as per the K-SADS-PL.

Safety assessments

Safety assessments from this study have been previously presented in detail and included assessment of AEs, findings from physical examinations, vital signs, clinical laboratory evaluations, and electrocardiograms (Wilens et al. 2012). AEs were assessed at each study visit. Treatment-emergent AEs (TEAEs) were defined as events that started or worsened between the day of the first dose of study medication and the third day after treatment cessation (inclusive).

Data analysis

The primary treatment group comparisons were:

• GXR a.m.+psychostimulant vs. placebo+psychostimulant

• GXR p.m.+psychostimulant vs. placebo+psychostimulant

Efficacy and safety analyses were performed on the full analysis set (FAS), defined as all subjects who received one or more doses of study medication. The final on-treatment assessment was defined as the last on-therapy, post-randomization treatment week, prior to any dose taper, at which a valid CPRS–R:L oppositional subscale score was collected, which is analogous to week 8 when applying the last-observation-carried-forward technique. Efficacy analyses were performed on the change from baseline to the final on-treatment assessment for the FAS, using the analysis of covariance model. Each between-treatment group comparison was evaluated at the 0.05 significance level. Effect sizes were calculated as the absolute difference in least square means between active treatment and placebo divided by the root mean square.

Results

The primary efficacy analysis of this study, which has been reported previously, indicated that based on the ADHD-RS-IV, adjunctive administration of GXR was associated with statistically significant reductions in ADHD symptoms in both the GXR a.m. plus psychostimulant group and the GXR p.m. plus psychostimulant group, compared with the placebo plus psychostimulant group (Wilens et al. 2012).

Overall, 461 subjects were randomized, and 455 subjects were included in the FAS. A total of 386 subjects completed the dose-maintenance period, and 378 subjects completed the follow-up visit, which occurred 7–9 days after the last dose of the study drug. At baseline, significant oppositional symptoms, defined as ≥1.5 SDs from age- and sex-normative values, were present in 60.2% (274/455) of subjects (86 subjects in the GXR a.m.+psychostimulant group, 93 subjects in the GXR p.m.+psychostimulant group, and 95 subjects in the placebo+psychostimulant group). Demographic characteristics in this subgroup with significant oppositional symptoms were generally similar among the three randomized treatment groups (Table 1). Based on results from the K-SADS-PL performed at screening, 19.8% (90/455) of subjects had ADHD with a comorbid diagnosis of ODD.

Table 1.

Key Demographics in Subjects with Significant Oppositional Symptoms at Baselinea (Subset of FAS)

| GXR a.m.+psychostimulant group (n=86) | GXR p.m.+psychostimulant group (n=93) | Placebo+psychostimulant group (n=95) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, y, mean (SD) | 10.8 (2.5) | 10.4 (2.3) | 10.8 (2.3) |

| Sex, n (%) | |||

| Male | 58 (67.4) | 65 (69.9) | 65 (68.4) |

| Female | 28 (32.6) | 28 (30.1) | 30 (31.6) |

| Race, n (%) | |||

| White | 58 (67.4) | 62 (66.7) | 65 (68.4) |

| Black or African American | 14 (16.3) | 22 (23.7) | 20 (21.1) |

| Native Hawaiian or Pacific Islander | 1 (1.2) | 1 (1.1) | 1 (1.1) |

| Asian | 1 (1.2) | 2 (2.2) | 1 (1.1) |

| American Indian or Alaskan Native | 1 (1.2) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) |

| Other | 11 (12.8) | 6 (6.5) | 8 (8.4) |

| Weight, kg, mean (SD) | 39.15 (12.22) | 38.04 (11.50) | 40.37 (13.26) |

Percentages may not total 100 because of rounding.

Significant oppositional symptoms were defined as a baseline Conners' Parent Rating Scale–Revised: Long Form oppositional subscale score ≥14 for boys or ≥12 for girls.

FAS, full analysis set; GXR, guanfacine extended release; SD, standard deviation.

Efficacy

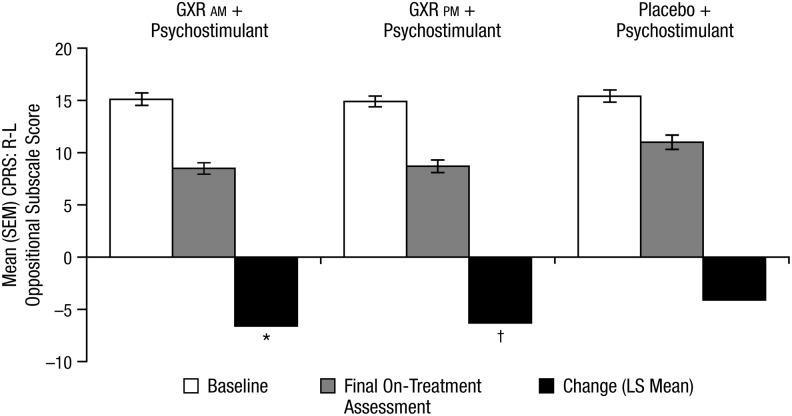

In the overall study population, significant improvement from baseline on the oppositional subscale of the CPRS–R:L was seen with GXR adjunctive to psychostimulant compared with placebo plus psychostimulant at week 8/final on-treatment assessment (Fig. 1). In the GXR a.m. plus psychostimulant group, the placebo-adjusted LS mean change from baseline to week 8/final on-treatment assessment was −2.4 (p=0.001, effect size=0.394). In the GXR p.m. plus psychostimulant group, the placebo-adjusted LS mean reduction from baseline to week 8/final on-treatment assessment was −2.2 (p=0.003, effect size=0.355).

FIG. 1.

Mean (SEM) oppositional subscale of the CPRS–R:L—FAS. SEM, standard error of the mean; CPRS–R:L, Conners' Parent Rating Scale–Revised: Long Form; FAS, full analysis set; GXR, guanfacine extended release; LS, least squares. *p<0.001 versus placebo+psychostimulant; †p=0.003 versus placebo+psychostimulant.

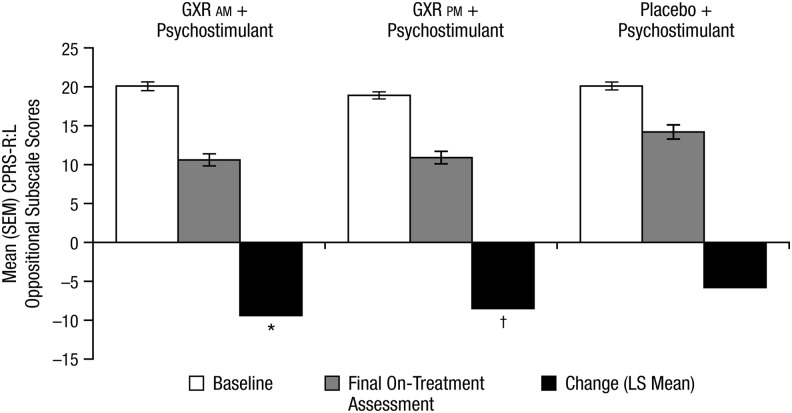

In the subgroup of subjects with significant oppositional symptoms at baseline, GXR plus psychostimulant showed significantly greater improvement from baseline on the CPRS–R:L compared with placebo plus psychostimulant at week 8/final on-treatment assessment (Fig. 2). In the GXR a.m. plus psychostimulant group, the placebo-adjusted LS mean change from baseline was −3.6 (p=0.001, effect size=0.521) at week 8/final on-treatment assessment. In the GXR p.m. plus psychostimulant group, the placebo-adjusted LS mean change from baseline was −2.7 (p=0.013, effect size=0.395) at week 8/final on-treatment assessment.

FIG. 2.

Mean (SEM) oppositional subscale of the CPRS–R:L – subjects with significant oppositional symptoms (subset of FAS). The final on-treatment assessment was defined as the last on-therapy, postrandomization treatment week, prior to any dose taper, at which a valid ADHD-RS-IV total score was collected. SEM, standard error of the mean; CPRS–R:L, Conners' Parent Rating Scale–Revised: Long Form; FAS, full analysis set; ADHD-RS-IV, Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder Rating Scale IV; GXR, guanfacine extended release; LS, least squares. *p=0.001 versus placebo+psychostimulant; †p=0.013 versus placebo+psychostimulant.

For the post-hoc analysis of subjects with a formal diagnosis of ODD, 90 subjects (GXR a.m.,n=33; GXR p.m., n=26; and placebo, n=31) had a current diagnosis of ODD noted at baseline for the study. The study was not powered to show differences in these subgroup analyses of the change from baseline on the CPRS–R:L oppositional subscale scores. At the week 8/final on-treatment assessment, the placebo-adjusted LS mean changes from baseline were −2.6 and −0.7, for the GXR a.m. plus psychostimulant group (n=33) and the GXR p.m. plus psychostimulant group (n=26), respectively.

Dosing

In this study, optimal dose was defined as a clinically significant reduction in ADHD symptoms with minimal side effects. The mean optimal doses of GXR for the overall study population have been previously reported (Wilens et al. 2012). For subjects with significant oppositional symptoms, the mean (SD) optimal dose of GXR was 3.3 (0.95) mg/day for GXR plus psychostimulant overall. Mean (SD) optimal doses in the GXR a.m. plus psychostimulant and GXR p.m. plus psychostimulant groups were 3.3 (1.00) mg/day and 3.2 (0.90) mg/day, respectively. The overall mean (SD) weight-adjusted optimal dose of GXR was 0.091 (0.0347) mg/kg (GXR a.m.+psychostimulant, 0.090 [0.0358] mg/kg; GXR p.m.+psychostimulant (0.091 [0.0337] mg/kg). The weight-adjusted optimal dose of GXR was between 0.09 mg/kg and 0.12 mg/kg for the largest percentage (41.8%) of subjects.

Safety

A detailed report of safety findings, including changes in pulse, blood pressure, and weight, have been previously reported (Wilens et al. 2012). In the overall study population, TEAEs were reported by 77.3% (116/150), 76.3% (116/152), and 63.4% (97/153) of subjects in the GXR a.m. plus psychostimulant, GXR p.m. plus psychostimulant, and placebo plus psychostimulant groups, respectively. The two most commonly reported TEAEs in each group were headache (21.3% [32/150]) and somnolence (14.0% [21/150]) in the GXR a.m. plus psychostimulant group, headache (21.1% [32/152]) and somnolence (13.2% [20/152]) in the GXR p.m.plus psychostimulant group, and headache (13.1% [20/153]) and upper respiratory tract infection (7.8% [12/153]) in the placebo plus psychostimulant group. The overall percentages of subjects reporting TEAEs, as well as TEAEs occurring in ≥5% of subjects in any of the treatment groups (GXR a.m.+psychostimulant, GXR p.m.+psychostimulant, and placebo+psychostimulant), for subjects with significant oppositional symptoms at baseline, are shown in Table 2. TEAEs were reported by 77.9% (67/86), 74.2% (69/93), and 66.3% (63/95) of subjects with significant baseline oppositional symptoms, respectively.

Table 2.

Treatment-Emergent Adverse Events (TEAEs) Occurring in ≥5% of Subjects with Significant Oppositional Symptoms at Baselinea in Any Treatment Group (Subset of FAS)

| GXR a.m.+psychostimulant group (n=86) | GXR p.m.+psychostimulant group (n=93) | Placebo+psychostimulant group (n=95) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Any TEAE, n (%) | 67 (77.9) | 69 (74.2) | 63 (66.3) |

| Headache | 17 (19.8) | 18 (19.4) | 12 (12.6) |

| Somnolence | 10 (11.6) | 11 (11.8) | 5 (5.3) |

| Upper respiratory tract infection | 6 (7.0) | 11 (11.8) | 8 (8.4) |

| Fatigue | 13 (15.1) | 8 (8.6) | 4 (4.2) |

| Insomnia | 4 (4.7) | 12 (12.9) | 6 (6.3) |

| Upper abdominal pain | 7 (8.1) | 9 (9.7) | 2 (2.1) |

| Dizziness | 10 (11.6) | 3 (3.2) | 5 (5.3) |

| Decreased appetite | 6 (7.0) | 7 (7.5) | 3 (3.2) |

| Cough | 4 (4.7) | 6 (6.5) | 4 (4.2) |

| Irritability | 4 (4.7) | 6 (6.5) | 9 (9.5) |

| Pyrexia | 4 (4.7) | 7 (7.5) | 4 (4.2) |

| Sedation | 2 (2.3) | 5 (5.4) | 2 (2.1) |

| Diarrhea | 5 (5.8) | 3 (3.2) | 1 (1.1) |

| Influenza | 3 (3.5) | 4 (4.3) | 5 (5.3) |

Significant oppositional symptoms were defined as a baseline Conners' Parent Rating Scale–Revised: Long Form oppositional subscale score ≥14 for boys or ≥12 for girls.

FAS, full analysis set; GXR, guanfacine extended release.

Most TEAEs were mild or moderate in severity. Serious AEs (SAEs) were reported in three subjects, all of whom were receiving GXR plus psychostimulant. One subject had an SAE of syncope, which occurred in the context of nausea, vomiting, and sinusitis. The second subject had SAEs of self-injurious behavior, aggression, homicidal ideation, and adjustment disorder with mixed disturbance of emotions and conduct; this subject had exhibited similar behaviors prior to study start. The third subject had an SAE of exposure to a toxic agent (i.e., poison ivy). In addition, there was an unintentional overdose in someone not a study subject. The brother of a study subject accidentally ingested eight 1 mg tablets of GXR; he was taken to the emergency room, given activated charcoal, observed, and released. No symptoms were reported. All of these SAEs were judged unrelated to GXR.

For the overall study population, the incidence of treatment-emergent somnolence, sedation, and hypersomnia (SSH) events combined was 18.0% (27/150) in the GXR a.m. plus psychostimulant group, 18.4% (28/152) in the GXR p.m. plus psychostimulant group, and 6.5% (10/153) in the placebo plus psychostimulant group. Most treatment-emergent SSH events occurred during the dose-optimization period (mean [SD] onset day, 19.6 [13.0], 15.9 [13.2], and 17.2 [10.6] with GXR a.m.+psychostimulant, GXR p.m.+psychostimulant, and placebo+psychostimulant, respectively), and most resolved prior to the dose-tapering period in all three groups (87.1%, 84.8%, and 75.0%, respectively). One discontinuation (0.7% [1/152]) occurred in the GXR p.m.+psychostimulant group because of a TEAE of somnolence.

Discussion

In subjects with ADHD and suboptimal response to a psychostimulant, GXR adjunctive to a psychostimulant significantly reduced oppositional symptoms compared with placebo plus a psychostimulant in both the overall subject population and a subgroup of patients with a significant level of oppositional symptoms at baseline on a psychostimulant alone. A post-hoc analysis of subjects with and without defined diagnoses of ODD found no significant improvement in oppositional symptoms in those with ODD; however, these subjects comprised only ∼20% of the FAS (90 of 455 subjects total). Although an absence of improvement in oppositional symptoms with GXR may be the case in patients with ODD, failure to detect a significant between–treatment-group difference in the subset of patients with ODD may have also been the result of insufficient statistical power to detect an actual difference.

As previously reported, no unique TEAEs were reported with adjunctive administration compared with those reported historically for either treatment alone (Wilens and Spencer 2000; Biederman et al. 2008; Sallee et al. 2009b; INTUNIV 2011). The overall rate of TEAEs as well as the types of TEAEs seen most frequently were comparable between the overall subject population and subjects with significant oppositional symptoms at baseline.

The findings in this analysis are consistent with those of an earlier controlled study by Connor and colleagues (2010) of GXR monotherapy in children with ADHD and a high level of oppositional symptoms wherein significant reductions in both the core symptoms of ADHD (i.e., inattention and hyperactivity-impulsivity) and oppositional symptoms were observed following treatment with GXR. A post-hoc analysis from that study reported a positive correlation (r = 0.74) between reductions in CPRS-R:L oppositional scores and ADHD-RS-IV scores (Connor et al. 2010). This is consistent with a meta-analysis of three placebo-controlled studies of atomoxetine in children and adolescents with ADHD, which showed correlations of similar magnitude between changes in oppositional and ADHD symptoms (Biederman et al. 2007).

Historically, monotherapy studies of psychostimulants and of atomoxetine for the treatment of oppositional symptoms have yielded mixed efficacy results (Kaplan et al. 2004; Spencer et al. 2006; Bangs et al. 2008; Lopez et al. 2008; Dell'Agnello et al. 2009; Hazell et al. 2009; Waxmonsky et al. 2010; Dittmann et al. 2011; Marchant et al. 2011; Waxmonsky et al. 2011; van Wyk et al. 2012). For example, in a randomized, double-blind, parallel-group, placebo-controlled study conducted in children and adolescents with ODD with or without coexisting ADHD (n=308), in the overall study population, mixed amphetamine salts (extended release) were associated with significant improvements in parent and teacher ratings on the ODD subscale of the Swanson, Nolan, and Pelham-IV (p<0.05) (Spencer et al. 2006). In subjects with ODD without ADHD, however, the treatment effect was not statistically significant. A controlled study of lisdexamfetamine dimesylate (LDX) evaluated oppositional symptoms in children 6–12 years with ADHD at different time points across the day as a secondary efficacy measure (Lopez et al. 2008). A post-hoc analysis of Conners' Parent Rating Scale–Revised: Short Form (CPRS-R:S) oppositional subscale scores found significant reductions with LDX compared with placebo at the 10 a.m. and 2 p.m. assessments, although not at the 6 p.m. assessment.

Kaplan et al, reported the results of a subset analysis of children with diagnoses of both ADHD and ODD (n=98) taken from two identical, double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled trials of atomoxetine. This subanalysis found significant differences between atomoxetine and placebo-treated groups in changes from baseline to endpoint on the ADHD-RS-IV (p<0.001) as well as on three of four of the CPRS-R:S subscales (ADHD Index, p=0.005; Cognitive, p=0.006; and Hyperactive, p=0.003). However, there were no significant differences between atomoxetine and placebo as measured by the CPRS–R:S oppositional subscale (Kaplan et al. 2004). In contrast, a randomized controlled study that also examined a population of children with diagnoses of both ADHD and ODD (n=226) found significantly greater changes from baseline on the ODD subscale of the Swanson, Nolan, and Pelham Rating Scale–Revised with atomoxetine than with placebo in an overall repeated-measures analysis (p=0.01), although a last-observation-carried-forward analysis found no significant difference between atomoxetine-treated and placebo-treated groups (Bangs et al. 2008). The results of additional studies of the effects of atomoxetine on oppositional symptoms in patients with ADHD are similarly inconsistent (Dell'Agnello et al. 2009; Hazell et al. 2009; Waxmonsky et al. 2010; Dittmann et al. 2011; Waxmonsky et al. 2011; van Wyk et al. 2012). Finally, a study of clonidine XR as adjunctive therapy to psychostimulants found significant reductions in mean CPRS total scores compared with placebo, but did not find similar significant reductions on the CPRS oppositional subscale (Kollins et al. 2011).

In this dose-optimization study of GXR adjunctive therapy, the mean optimal doses of GXR appeared similar between subjects with significant oppositional symptoms and the overall study population. As previously reported (Wilens et al. 2012), the mean (SD) optimal dose of GXR was 3.2 (1.0) mg/day for the overall study population (Wilens et al. 2012). For subjects with significant oppositional symptoms, the mean (SD) optimal dose of GXR was 3.3 (0.95) mg/day for GXR plus psychostimulant overall. Although these data are confounded by the fact that the group of subjects with oppositional symptoms is a subset of the overall study population, they indicate that similar doses of GXR can be effective in patients with ADHD with or without significant oppositional symptoms.

Limitations

Some limitations to this analysis merit comment. First, although almost 20% of subjects had a comorbid diagnosis of ODD in addition to a diagnosis of ADHD, no subjects had a diagnosis of ODD alone. Therefore, the results of this study cannot be extrapolated to an ODD population without comorbid ADHD (Martel et al. 2010). Second, there is the possibility of “pseudospecificity,” meaning that it is conceivable that improvements in ADHD symptoms might have resulted in reductions in oppositional symptoms. In addition, this data set cannot address whether psychostimulant monotherapy had resulted in reductions in oppositional symptoms before study enrollment. Therefore, the reductions observed may have been in addition to any improvements that had occurred on psychostimulant alone, and comparisons of effect size with monotherapy studies may be inappropriate. This study also did not take into account additional clinical characteristics (i.e., co-existing anxiety issues, learning disabilities) and life circumstances (i.e., home life stability) that may contribute to oppositional behavior and thus confound the ability to detect treatment efficacy in certain individuals. Although inclusion criterion specified a suboptimal response to psychostimulant monotherapy, no evidence of optimal titration to psychostimulant therapy was required prior to enrollment. In addition, adherence with psychostimulant therapy before the study start also was not assessed. Therefore, participation in the study could have increased adherence to psychostimulants, producing an artificially enhanced placebo response in the psychostimulant plus placebo group. Also, there is a possibility that investigators may have inadvertently introduced bias in their assessment and selection of acceptable subjects for inclusion in the study. Although measures were taken to ensure that the study was blind, there is also the possibility that the blinding may have been suboptimally maintained, based upon observed side effects such as somnolence. Finally, whereas numerically greater decreases in measures of oppositional symptoms were seen in the GXR a.m. plus psychostimulant arm, this study was not designed or powered to evaluate a.m. versus p.m. administration, and no conclusion can be drawn regarding the relative superiority of either dosing regimen.

Conclusions

In children and adolescents with ADHD and suboptimal response to a psychostimulant, addition of GXR to a psychostimulant significantly reduced oppositional symptoms compared with placebo plus a psychostimulant in the overall study population. Significant efficacy as measured by the oppositional subscale of the CPRS–R:L was also demonstrated in the subgroup of subjects presenting with significant oppositional symptoms at baseline. No unique TEAEs were reported with adjunctive administration compared with those reported historically for either treatment alone (Wilens and Spencer 2000; Biederman et al. 2008; Sallee et al. 2009b; INTUNIV 2011). The rates as well as types of TEAEs reported most frequently were comparable among the overall subject population and in the subset of subjects with significant oppositional symptoms at baseline.

Clinical Significance

The clinical core symptomatology of ADHD is often accompanied by oppositional symptoms, which may impair academic and social functioning. Although psychostimulants are considered first-line pharmacotherapy for ADHD, many patients do not experience adequate symptom amelioration with drug monotherapy.

In the current study, GXR adjunctive to a psychostimulant significantly reduced oppositional symptoms compared with placebo plus a psychostimulant in subjects with ADHD and suboptimal response to psychostimulant monotherapy, who also present with significant oppositional symptoms.

Acknowledgments

Under author direction, Asha Philip, PharmD, Jennifer Steeber, PhD, and Michael Pucci, PhD, of SCI Scientific Communications & Information (SCI), and Melissa Brunckhorst, PhD, of MedErgy, provided writing assistance for this publication. Editorial assistance in the form of proofreading, copy editing, and fact checking was also provided by SCI and MedErgy. Ryan Dammerman, MD, PhD, formerly of Shire and Gina D'Angelo, PharmD, of Shire also reviewed and edited the manuscript for scientific accuracy. Andrew Lyne, MSc, CStat, and Catherine Leeming-Price, BSc, of Shire are acknowledged for their statistical work on this study. With great sadness, the authors wish to acknowledge the passing of Carla White, BSc, CStat, and recognize her contributions to this article.

Disclosures

Dr. Findling receives or has received research support, acted as a consultant and/or served on a speaker's bureau for Alexza Pharmaceuticals, American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, American Physician Institute, American Psychiatric Press, AstraZeneca, Bracket, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Clinsys, Cognition Group, Coronado Biosciences, Dana Foundation, Forest, GlaxoSmithKline, Guilford Press, Johns Hopkins University Press, Johnson & Johnson, KemPharm, Lilly, Lundbeck, Merck, National Institutes of Health (NIH), Novartis, Noven, Otsuka, Oxford University Press, Pfizer, Physicians Postgraduate Press, Rhodes Pharmaceuticals, Roche, Sage, Seaside Pharmaceuticals, Shire, Stanley Medical Research Institute, Sunovion, Supernus Pharmaceuticals, Transcept Pharmaceuticals, Validus, and WebMD. Dr. McBurnett has consulted for and has received honoraria from Eli Lilly, Lexicor, McNeil Pediatrics, and Shire. He has received grants from Abbott, Cephalon, Eli Lilly, Johnson & Johnson, McNeil Pediatrics, National Institute of Mental Health, New River, Otsuka, Shire, and Sigma-Tau. Ms. White, deceased, was a consultant for Shire Pharmaceutical Development Ltd, Basingstoke, United Kingdom. Dr. Youcha was an employee of Shire at the time of the study, and previously held stock and/or stock options in Shire.

References

- American Psychiatric Association: Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 4th ed. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 1994 [Google Scholar]

- Bangs ME, Hazell P, Danckaerts M, Hoare P, Coghill DR, Wehmeier PM, Williams DW, Moore RJ, Levine L: Atomoxetine for the treatment of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder and oppositional defiant disorder. Pediatrics 121:e314–e320, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biederman J, Melmed RD, Patel A, McBurnett K, Konow J, Lyne A, Scherer N: A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study of guanfacine extended release in children and adolescents with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Pediatrics 121:e73–e84, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biederman J, Spencer TJ, Newcorn JH, Gao H, Milton DR, Feldman PD, Witte MM: Effect of comorbid symptoms of oppositional defiant disorder on responses to atomoxetine in children with ADHD: A meta-analysis of controlled clinical trial data. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 190:31–41, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cantwell DP: Attention deficit disorder: A review of the past 10 years. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 35:978–987, 1996 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention: Increasing prevalence of parent-reported attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder among children – United States, 2003 and 2007. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 59:1439–1443, 2010 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conners CK: Conners Rating Scales–Revised. Toronto, ON: Multi-Health Systems, Inc.; 1997 [Google Scholar]

- Connor DF, Doerfler LA: ADHD with comorbid oppositional defiant disorder or conduct disorder: Discrete or nondistinct disruptive behavior disorders? J Atten Disord 12:126–134, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Connor DF, Findling RL, Kollins SH, Sallee F, Lopez FA, Lyne A, Tremblay G: Effects of guanfacine extended release on oppositional symptoms in children aged 6–12 years with attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder and oppositional symptoms: A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. CNS Drugs 24:755–768, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dell'Agnello G, Maschietto D, Bravaccio C, Calamoneri F, Masi G, Curatolo P, Besana D, Mancini F, Rossi A, Poole L, Escobar R, Zuddas A: Atomoxetine hydrochloride in the treatment of children and adolescents with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder and comorbid oppositional defiant disorder: A placebo-controlled Italian study. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol 19:822–834, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dittmann RW, Schacht A, Helsberg K, Schneider–Fresenius C, Lehmann M, Lehmkuhl G, Wehmeier PM: Atomoxetine versus placebo in children and adolescents with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder and comorbid oppositional defiant disorder: A double-blind, randomized, multicenter trial in Germany. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol 21:97–110, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harpold T, Biederman J, Gignac M, Hammerness P, Surman C, Potter A, Mick E: Is oppositional defiant disorder a meaningful diagnosis in adults? Results from a large sample of adults with ADHD. J Nerv Ment Dis 195:601–605, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hazell P, Becker K, Nikkanen EA, Trzepacz PT, Tanaka Y, Tabas L, D'Souza DN, Witcher J, Long A, Ponsler G, Dittmann RW: Relationship between atomoxetine plasma concentration, treatment response and tolerability in attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder and comorbid oppositional defiant disorder. Atten Defic Hyperact Disord 1:201–210, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- INTUNIV: INTUNIV® (guanfacine) extended-release tablets [package insert]. Wayne, PA: Shire Pharmaceuticals LLC; 2011 [Google Scholar]

- Kaplan S, Heiligenstein J, West S, Busner J, Harder D, Dittmann R, Casat C, Wernicke JF: Efficacy and safety of atomoxetine in childhood attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder with comorbid oppositional defiant disorder. J Atten Disord 8:45–52, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kollins SH, Jain R, Brams M, Segal S, Findling RL, Wigal SB, Khayrallah M: Clonidine extended-release tablets as add-on therapy to psychostimulants in children and adolescents with ADHD. Pediatrics 127:e1406–e1413, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lopez FA, Ginsberg LD, Arnold V: Effect of lisdexamfetamine dimesylate on parent-rated measures in children aged 6 to 12 years with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: A secondary analysis. Postgrad Med 120:89–102, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marchant BK, Reimherr FW, Robison RJ, Olsen JL, Kondo DG: Methylphenidate transdermal system in adult ADHD and impact on emotional and oppositional symptoms. J Atten Disord 15:295–304, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martel MM, Gremillion M, Roberts B, von EA, Nigg JT: The structure of childhood disruptive behaviors. Psychol Assess 22:816–826, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pliszka SR, Crismon ML, Hughes CW, Corners CK, Emslie GJ, Jensen PS, McCracken JT, Swanson JM, Lopez M: The Texas Children's Medication Algorithm Project: Revision of the algorithm for pharmacotherapy of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 45:642–657, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sallee FR, Lyne A, Wigal T, McGough JJ: Long-term safety and efficacy of guanfacine extended release in children and adolescents with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol 19:215–226, 2009a [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sallee FR, McGough J, Wigal T, Donahue J, Lyne A, Biederman J: Guanfacine extended release in children and adolescents with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: A placebo-controlled trial. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 48:155–165, 2009b [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scahill L, Chappell PB, Kim YS, Schultz RT, Katsovich L, Shepherd E, Arnsten AF, Cohen DJ, Leckman JF: A placebo-controlled study of guanfacine in the treatment of children with tic disorders and attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. Am J Psychiatry 158:1067–1074, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spencer TJ, Abikoff HB, Connor DF, Biederman J, Pliszka SR, Boellner S, Read SC, Pratt R: Efficacy and safety of mixed amphetamine salts extended release (Adderall XR) in the management of oppositional defiant disorder with or without comorbid attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder in school-aged children and adolescents: A 4-week, multicenter, randomized, double-blind, parallel-group, placebo-controlled, forced-dose-escalation study. Clin Ther 28:402–418, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spencer TJ, Greenbaum M, Ginsberg LD, Murphy WR: Safety and effectiveness of coadministration of guanfacine extended release and psychostimulants in children and adolescents with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol 19:501–510, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steiner H, Remsing L: Practice parameter for the assessment and treatment of children and adolescents with oppositional defiant disorder. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 46:126–141, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Wyk GW, Hazell PL, Kohn MR, Granger RE, Walton RJ: How oppositionality, inattention, and hyperactivity affect response to atomoxetine versus methylphenidate: A pooled meta-analysis. J Atten Disord 16:314–324, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waxmonsky JG, Waschbusch DA, Akinnusi O, Pelham WE: A comparison of atomoxetine administered as once versus twice daily dosing on the school and home functioning of children with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol 21:21–32, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waxmonsky JG, Waschbusch DA, Pelham WE, Draganac–Cardona L, Rotella B, Ryan L: Effects of atomoxetine with and without behavior therapy on the school and home functioning of children with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. J Clin Psychiatry 71:1535–1551, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilens TE, Bukstein O, Brams M, Cutler AJ, Childress A, Rugino T, Lyne A, Grannis K, Youcha S: A controlled trial of extended-release guanfacine and psychostimulants for attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 51:74–85, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilens TE, Spencer TJ: The stimulants revisited. Child Adolesc Psychiatr Clin N Am 9:573–603, viii, 2000 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]