Abstract

In this study, we demonstrate that the pervasive xenobiotic methoxyacetic acid and the commonly prescribed anticonvulsant valproic acid, both short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs), dramatically increase cellular sensitivity to estrogens, progestins, and other nuclear hormone receptor ligands. These compounds do not mimic endogenous hormones but rather act to enhance the transcriptional efficacy of ligand activated nuclear hormone receptors by up to 8-fold in vitro and in vivo. Detailed characterization of their mode of action revealed that these SCFAs function as both activators of p42/p44 mitogen-activated protein kinase and as inhibitors of histone deacetylases at doses that parallel known exposure levels. Our results define a class of compounds that possess a dual mechanism of action and function as hormone sensitizers. These findings prompt an evaluation of previously unrecognized drug–drug interactions in women who are administered exogenous hormones while exposed to certain xenobiotic SCFAs. Furthermore, our study highlights the need to structure future screening programs to identify additional hormone sensitizers.

Numerous studies suggest an association between exposure to exogenous estrogens and an increased risk of breast cancer (1, 2). Notably, the interim results from the Women's Health Initiative indicate a significant increase in the incidence of invasive breast cancer in postmenopausal women receiving hormone therapy (HT), which describes medicines where an estrogen is administered with a progestin (3). Furthermore, large-scale clinical studies have suggested an increased risk of negative cardiovascular events in women administered HT (3, 4). Although substantially positive effects were observed in these reports with respect to the incidence of colon cancer and prevention of osteoporosis, a general consensus indicates that the risks associated with HT outweigh the benefits in postmenopausal women. Until improved HT formulations are available, there is an unmet need to identify patients who may be at risk for adverse effects of traditional estrogen therapy or HT. Several groups have taken a genetic approach to identify predispositions to adverse effects of estrogens and progestins (5). As a complimentary strategy, we considered whether cellular/tissue sensitivity to estrogens and progestins can be influenced by frequently encountered xenobiotics or drugs that may predispose patients to untoward side effects of exogenous hormones.

A unified model of estrogen receptor (ER) and progesterone receptor (PR) action proposes that ligand binding to the nuclear receptor (NR) induces a conformational change within the receptor. The receptor can then interact with specific DNA-response elements within the regulatory regions of target genes and facilitate the assembly of a large coactivator complex. The composition and subsequently the function of these receptor–coactivator complexes can be influenced by many factors, including: (i) the overall structure of the liganded receptor, (ii) the relative and absolute expression level of the constituent partners, (iii) the promoter and the chromatin context of the DNA bound receptors, and (iv) the impact of other signaling pathways on receptors and their associated cofactors, i.e., phosphorylation (6, 7). Given the complexity of the steroid hormone receptor signal transduction pathways, we tested the hypothesis that xenobiotics that do not compete with endogenous hormones might have a dramatic impact on steroid hormone signaling.

Materials and Methods

Cell Culture and Transient Transfection. All cell lines were maintained as described (8). For alkaline phosphatase assays, RT-PCR analysis, and microarray analysis, T47D cells were cultured in phenol-red free DMEM supplemented with 10% dextranstripped FBS (HyClone Laboratories) for 3 days before addition of compound. For all experiments analyzing Elk1 or extracellular signal-regulated kinase (ERK)1/2 activity, cells were preincubated for 24 h in medium supplemented with 0.5% charcoal-stripped FBS (HyClone Laboratories). The protocol for transient transfections is described in detail in Supporting Materials and Methods, which is published as supporting information on the PNAS web site. Luciferase and β-galactosidase activities were assayed as described (9). All data shown are representative of at least three independent experiments.

Chemicals. Methoxyacetic acid (MAA), valproic acid (VPA) sodium salt, sodium butyrate, trichostatin A (TSA), valpromide (VPD), RU486, R5020, 17β-estradiol, 4-hydroxy-tamoxifen, 4-nitrophenyl phosphate, U0126, and SB203580 were purchased from Sigma. SP600125 was purchased from Calbiochem, R5020 was purchased from NEN Life Science Products, and ICI 182,780 was obtained from Tocris. Epidermal growth factor (EGF) was purchased from Invitrogen, and 2,2-Di-N-propylacetamide (VPD) was purchased from Lancaster Synthesis.

Plasmids. The mammalian expression plasmids for ER and PR, their respective luciferase reporters, and pCMV-β-galactosidase have been described (10). The pBSKII plasmid, the pFR luciferase reporter, and pFA2-Elk1 were purchased from Stratagene. The pCDNA3-flag histone deacetylase (HDAC) expression vectors were generously provided by T.-P. Yao (Duke University Medical Center).

Alkaline Phosphatase Assay. T47D cells were seeded into 96-well plates at 10,000 cells per well in phenol-red free DMEM supplemented with 10% dextran-stripped FBS (HyClone Laboratories) 4 days before analysis of alkaline phosphatase activity. A colorimetric alkaline phosphatase assay was performed 24 h after treatment with compound, as described in Supporting Materials and Methods.

RNA Isolation and Real-Time RT-PCR. Total RNA was isolated from CD-1 mouse uterine tissue or from T47D cells according to the manufacturer's instructions for the RNaqueous system (Ambion). Total RNA from each sample was reversed transcribed by using the First-Strand synthesis system (Invitrogen). Details of the real-time PCR amplification reactions and the sequences for gene-specific primers are provided in Supporting Materials and Methods.

Histone Extraction and HDAC Activity Assay. Histone proteins were isolated by acid extraction and were immunoblotted as described in Supporting Materials and Methods. For HDAC activity assays, overexpressed HDACs were immunoprecipitated as described in detail in Supporting Materials and Methods. HDAC activity was assayed according to the manufacturer's protocol for the HDAC fluorescent activity assay/drug discovery kit (Biomol, Plymouth Meeting, PA).

Ras Pull-Down Assay. Cultured HeLa cells were washed with 1× Tris-buffered saline and lysed in 20 mM Hepes, pH 7.9/20% glycerol/400 mM KCl/1 mM EDTA/1 mM DTT/protease inhibitors (Roche Applied Science). Ras pull-down experiments were performed with the EZ-detect Ras activation kit from Pierce according to the manufacturer's protocol. Ras protein was analyzed on an SDS/12% PAGE gel and was probed with a pan-Ras antibody from Sigma.

Statistics. For the in vivo mouse studies, ANOVA was performed by using statview software (SAS Institute, Cary, NC). Planned comparisons were conducted by using Fisher's planned least significant difference test when the overall ANOVA was statistically significant. A one-tailed Student t test was performed to analyze the significance of luciferase induction.

Results

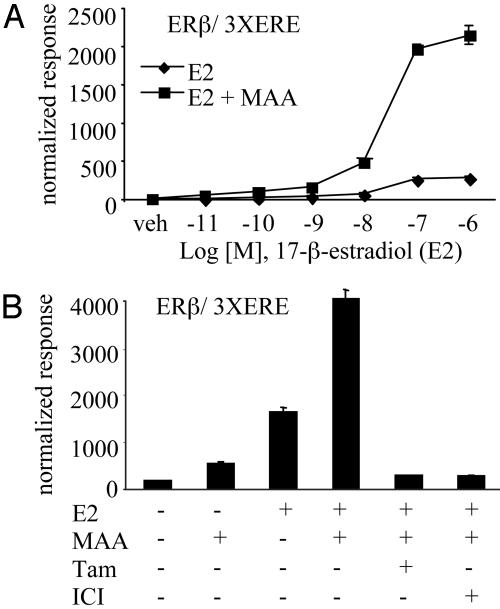

Xenobiotics Can Function as Hormone Sensitizers. We developed a robust cell-based assay to identify compounds that could alter the efficacy of an estrogen-activated ER. Specifically, we cotransfected an estrogen-responsive reporter gene driven by three copies of a consensus estrogen-response element (3× ERE) and an ERβ expression plasmid into human hepatic carcinoma (HepG2) cells. Selected compounds were tested for their ability to enhance the transcriptional efficacy of the ERβ–estradiol complex. In this study, we focused our attention on chemicals that have previously been shown to impact reproductive function in vivo. Our initial studies led us to ethylene glycol monomethyl ether (EGME), a pervasive industrial solvent found in varnishes, paints, dyes, and fuel additives. Exposure to this compound and its primary metabolite MAA induce severe reproductive toxicity in both humans and rodents (11, 12). Based on reports that toxic doses of EGME give rise to 5 mM MAA plasma levels in rodents and that similar concentrations of MAA are observed in the urine of humans after occupational EGME exposure (13, 14), we treated cells with 5 mM MAA to achieve comparable MAA levels for our studies. Cotransfection studies revealed that MAA potentiated the 17-β-estradiol-mediated activation of ERβ transcriptional activity (30-vs. 230-fold induction) at saturating hormone concentrations when assessed on a classical ERE reporter (Fig. 1A). In this cell background, the antiestrogen ICI 182,780 or the SERM 4-hydroxy-tamoxifen completely inhibited ER transcriptional activity, regardless of the presence of MAA, confirming that the actions of MAA in this system were entirely receptor-dependent (Fig. 1B).

Fig. 1.

MAA alters a fundamental aspect of NR activity and potentiates NR transactivation in cell-based assays. (A) HepG2 cells were cotransfected with a luciferase reporter gene driven by 3× ERE and ERβ. Cells were treated with increasing concentrations of 17-β-estradiol (E2) in the absence (♦) or presence (▪) of 5 mM MAA for 24 h. (B) HepG2 cells were transfected and treated as in A with the addition of 1 μM 4-hydroxy-tamoxifen (Tam) or 1 μM ICI 182,780 (ICI) to inhibit the E2 (100 nM) and MAA responses. Normalized luciferase activities are presented as the averages of triplicate transfections ± SEM.

The effect of MAA on ERβ is not ER isoform-specific because MAA potentiated estradiol-induced ERα activity and also enhanced tamoxifen partial agonist activity on ERα (Fig. 6 A and B, which is published as supporting information on the PNAS web site). To support our hypothesis that MAA's action is pantrophic in nature, we observed that MAA enhanced the ligand-mediated transcriptional activities of many other NRs, including receptors for thyroid hormone receptor (TRβ) and androgen receptor (Fig. 6 C and D). Our results indicate that MAA is not merely a hormone mimetic because it shows minimal NR activation in the absence of cognate ligand (Fig. 1 A and B). We supported this conclusion with whole-cell binding assays in which MAA did not compete for 17-β-estradiol binding to ER (Fig. 7, which is published as supporting information on the PNAS web site). In addition, we showed by protease digestion that incubation of ERβ with MAA did not induce a receptor conformation different from unliganded receptor (Fig. 8, which is published as supporting information on the PNAS web site). More importantly, we demonstrated that MAA was able to potentiate ERβ and also PRB transcriptional activity at saturating levels of their respective agonists (Figs. 1 A and 2 A). Although the efficacy of each agonist was enhanced, we observed no change in the potency (EC50) of the receptor ligands in the presence of MAA. For example, the EC50 values for the estradiol dose–response curves in the absence or presence of MAA = 24 and 28 nM, respectively (Fig. 1 A). From these results, we conclude that MAA exerts its effects on NR signaling at a step other than ligand binding.

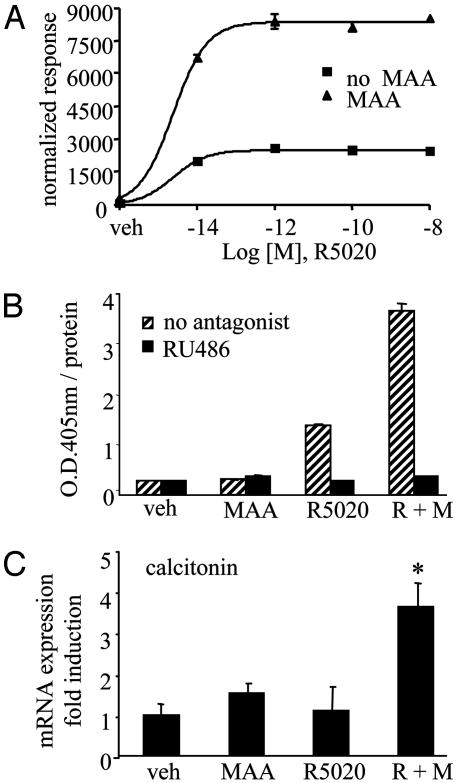

Fig. 2.

MAA mediates a striking potentiation of ligand-induced PRB activity in vitro and in vivo. (A) HepG2 cells were cotransfected with a luciferase reporter gene driven by two copies of a consensus progesterone-response element and PRB. Cells were treated with vehicle and increasing concentrations of the synthetic progestin R5020 either in the absence (▪) or presence (▴) of 5 mM MAA for 24 h. Normalized luciferase activities are presented as the averages of triplicate transfections ± SEM. (B) T47D cells were treated for 24 h with vehicle, 10 nM R5020, 5 mM MAA, or a combination of R5020 plus MAA in the absence (striped bars) or presence (filled bars) of 1 μM antiprogestin RU486. Normalized alkaline phosphatase activity is presented as the averages of quadruplicate wells ± SEM. (C) CD-1 mice were injected with compound as described in Supporting Materials and Methods. Real-time quantitative RT-PCR was performed for the mouse calcitonin gene, n = 5 for each treatment group. *, P <0.05.

MAA Alters the Hormone Sensitivity of Endogenously Expressed PR in Vitro and in Vivo. We next investigated the effects of MAA on endogenous progesterone-responsive targets in T47D cells, a human breast cancer cell line that expresses PR. We observed at least a 2-fold increase in PR-mediated alkaline phosphatase activity (15) on treatment of T47D cells with MAA and saturating concentrations of R5020 over that of R5020-induced activity alone (Fig. 2B). The alkaline phosphatase activity induced by either R5020 treatment alone or that observed in the presence of R5020 and MAA was completely inhibited by the addition of the PR antagonist RU486. Similarly, we analyzed MAA's effect on mRNA expression of the PR-responsive S100P gene. By real-time PCR analysis, we observed a 2-fold MAA-mediated potentiation above the R5020 induction of the S100P gene (Fig. 9, which is published as supporting information on the PNAS web site). These studies were supported by microarray analysis in which we queried the expression level of 19,000 mRNAs from T47D cells as described in detail in Supporting Materials and Methods. Surprisingly, MAA treatment alone had minimal effects on gene expression, altering the expression of only three transcripts after a 24-h exposure to the compound (Table 1, and Table 2, which is published as supporting information on the PNAS web site). This result supports our hypothesis that MAA's effects on NR activity are not due to general derepression of gene transcription. Furthermore, we observed that MAA led to a superinduction of 16 R5020-activated PR-responsive genes, as indicated by a comparison of the R5020 plus MAA treatment group vs. the R5020 treatment group (Tables 1 and 2). The S100P gene is representative of this class of superinduced genes, and microarray analysis revealed a 3.3-fold induction of S100P transcript expression with R5020 treatment, and a 10.3-fold induction with the combination treatment of R5020 and MAA. More importantly, we observed that four genes were induced only when both MAA and R5020 were coadministered (Tables 1 and 2). Thus, in addition to increasing the efficacy of PR-mediated gene transcription, MAA can change the target gene specificity of this receptor. Cumulatively, these studies confirm that MAA's action on PR signaling is not an artifact of receptor overexpression or of transfected reporters, and that MAA can regulate endogenous gene expression.

Table 1. MAA alters the R5020-regulated gene expression profile in T47D cells.

| Treatment comparison | No. of significantly altered transcripts |

|---|---|

| MAA vs. vehicle | 3 |

| R5020 vs. vehicle | 61 |

| R5020 plus MAA vs. vehicle (total) | 88 |

| R5020 plus MAA vs. vehicle (only induced in presence of both compounds) | 4* |

| R5020 plus MAA vs. R5020 (superinduced transcripts) | 16* |

Data represent results from a microarray analysis by using human breast cancer T47D cell RNA hybridized on a human 19,000 gene Oligo/Tox Chip (National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences). Significant transcript regulation at 24 h is based on outlier comparisons described in Supporting Materials and Methods.

Significant changes in gene expression between treatment groups were determined by t test analysis (P < 0.05)

To further test that MAA potentiates PR-mediated responses in a physiological context, we investigated the effect of this compound on progesterone-regulated gene expression in CD-1 mice. Previous reports (16) have demonstrated that PR mediates the induction of both calcitonin mRNA and protein levels in rodent uteri. Thus, we examined the effect of MAA treatment on the expression of calcitonin mRNA levels in the uteri of immature, female CD-1 mice. This model system enabled us to study MAA effects in cells expressing low levels of PR and under conditions where estradiol-dependent regulation of receptor levels was insignificant. We injected 21-day-old animals with vehicle, R5020, MAA, or with a combination of R5020 and MAA 6 h before harvesting the uterine total RNA. We performed quantitative real-time PCR and, as expected with immature mice and short-term exposure to progestins, we did not observe a significant up-regulation of calcitonin RNA levels in the presence of R5020 alone (Fig. 2C). Importantly however, calcitonin gene expression was elevated only when the mice were treated with a combination of MAA and R5020 (Fig. 2C). We did not observe an MAA-mediated change in gene expression of another progesterone-responsive uterine gene histidine decarboxylase (M.S.J., S.C.N., and D.P.M., unpublished data), indicating some degree of specificity in the target gene response to MAA in vivo.

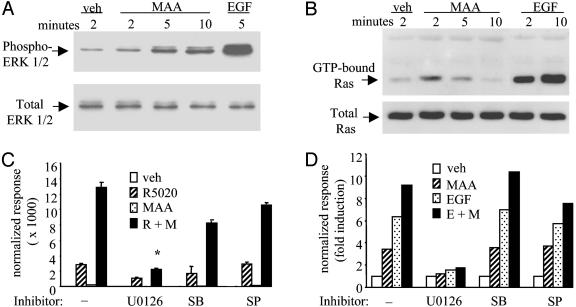

The Mitogen-Activated Protein Kinase (MAPK) Signaling Pathway Is Involved in MAA-Mediated Potentiation of NR Transcriptional Activity. The pantrophic nature of MAA effects on NRs suggested that this compound affects a fundamental aspect of NR action. Recent studies (17–19) have shown that agonist-mediated NR responses are enhanced in cells after MAPK activation. To probe MAA's ability to function as a small-molecule activator of MAPK signaling, we analyzed whether MAA could alter the phosphorylation status of ERK1/2. We detected an increase in activated ERK1/2 with maximal responses observed at 10 min of treatment (Fig. 3A). In addition, we tested whether MAA could activate Ras, a small GTPase responsible for integrating signals required for MAPK activation. In pull-down experiments of activated Ras (GTP-bound Ras), we observed a transient increase in the levels of activated Ras in HeLa cells treated with MAA (Fig. 3B). The MAA-mediated increase in Ras activation occurred at 2–5 min, which is consistent with the observed 5–10 min increase in MAA-induced ERK1/2 phosphorylation.

Fig. 3.

The ERK1/2 MAPK signaling pathway is involved in MAA-mediated potentiation of NR transcriptional activity. (A) HeLa cells were treated with vehicle, 100 ng/ml EGF, or 5 mM MAA for the time indicated. Whole-cell lysates were probed by Western blot analysis with antibodies against phosphorylated (phospho-Tyr-204) ERK 1/2 (Santa Cruz Biotechnology) or total ERK 1/2 (Promega). (B) HeLa cells were treated as in A for the time indicated. Levels of activated Ras (GTP-Ras) were visualized with a pan-Ras antibody. (C) HepG2 cells were cotransfected with two copies of a consensus progesterone-response element and PRB. Cells were treated with 100 nM R5020 (R) in the presence or absence of 5 mM MAA (M) for 24 h. Also, 5 μM U0126, 20 μM SB203580 (SB), or 2 μM SP600125 (SP) were added to the cells 10 min before R5020 and MAA treatments. *, P <0.005, t test. (D) HeLa cells were cotransfected with pFR-Luc and pFA2-Elk1. Cells were treated with 5 mM MAA (M), 100 ng/ml EGF (E), or a combination of these two compounds in the presence or absence of kinase inhibitors. Normalized luciferase activities are presented as the averages of triplicate transfections ± SEM.

We next investigated the role of the MAPK signaling pathway in the MAA-mediated potentiation of NR action. We observed that U0126 (a MEK1/2 MAP kinase, inhibitor) significantly blocked the MAA-induced potentiation of the R5020-activated PRB transcriptional response by 60% in a progesterone-response element reporter assay (Fig. 3C). Inhibitors of c-jun N-terminal kinase or p38 MAPK did not affect the ability of MAA to potentiate the R5020-PRB response (Fig. 3C). In parallel experiments investigating endogenous alkaline phosphatase activity in T47D cells, we again observed no effect of U0126 on PR activity in the presence of R5020 alone, although at least 50% of the MAA-mediated potentiation of PR activity was blocked by U0126 (M.S.J. and D.P.M., unpublished data). In support of the finding that active MEK 1/2 is required for MAA activity on NRs, coexpression of a dominant-negative Ras mutant also inhibited the MAA potentiation of PRB activity (M.S.J. and D.P.M., unpublished data). Our results show that although MAPK activation plays a significant role in MAA function, MAPK activation alone was not sufficient to account for the total potentiative effect of MAA on PR signaling.

To further test our hypothesis that MAA's activity as an endocrine disruptor is not exclusively attributable to direct effects on NRs, we examined the ability of MAA to affect the transcriptional activity of Elk-1, a downstream target of the ERK1/2 MAPK (Fig. 3D). We observed that MAA alone was able to activate Elk-1 transcriptional activity and that this response could be inhibited completely by U0126 (Fig. 3D). Inhibitors of other MAPKs had no effect in our system. As expected, EGF was able to regulate Elk-1 activity; however, the addition of MAA and EGF together led to an additive activation of Elk-1. The observation that MAA enhances the maximal EGF response indicates that MAA is not merely mimicking the EGF-mediated activation of MAPK signaling.

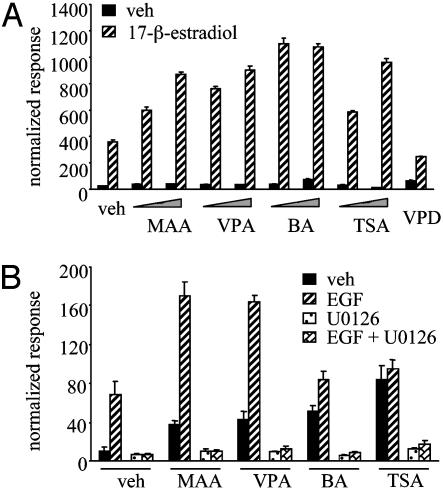

MAA Is Structurally Similar to Other Short-Chain Fatty Acids (SCFAs) That Potentiate NR Activity. Our results from the pharmacological disruption of the MAPK signaling pathway suggested that MAPK activation alone is necessary but not sufficient for the MAA-mediated potentiation of NR activity. Thus, to further explore the mechanism of MAA action on NR signaling, we compared the cell-based activity of structurally similar SCFAs. The widely prescribed antiepileptic and mood stabilizer VPA was of particular interest in this group of SCFAs. In addition, butyric acid (BA) is a physiologically relevant SCFA that is produced at high concentrations (between 2 and 12 mM) in the human colon (20). Both VPA and BA are documented HDAC inhibitors (21, 22), as is TSA, a structurally unrelated control inhibitor. We tested the ability of each of these compounds to stimulate ligand-mediated NR responses by using cotransfected ERβ and a 3× ERE luciferase reporter in HepG2 cells. We used 2 mM VPA because this closely corresponds to therapeutic plasma concentrations of this compound (23, 24). These additional SCFAs and TSA had strikingly similar abilities to potentiate ERβ activity compared with MAA (Fig. 4A). To emphasize the importance of the carboxylic acid component of these compounds, VPD, an amide derivative of VPA, was unable to enhance ligand-dependent NR signaling (Fig. 4A).

Fig. 4.

SCFAs potentiate ligand-dependent NR activity and possess subtle differences in their mechanisms of transcriptional activation. (A) HepG2 cells were cotransfected with the 3× ERE and ERβ. Cells were treated with vehicle, 5 mM MAA, 2 mM VPA, 5 mM BA, or 300 nM TSA in the absence or presence of 100 nM 17-β-estradiol (E2) for 24 h. (B) HeLa cells were cotransfected with pFR-Luc and pFA2-Elk1. Cells were treated with vehicle, 5 mM MAA, 2 mM VPA, 5 mM BA, or 300 nM TSA alone or in combination with 100 ng/ml EGF in the presence or absence of 5 μM U0126. Normalized luciferase activities are presented as the averages of triplicate transfections ± SEM.

To compare the role of different SCFAs in MAPK activation, we tested MAA, VPA, and BA in the Elk1 reporter assay. Both MAA and VPA treatment yielded nearly identical results in this assay (Fig. 4B). Interestingly, BA and TSA were able to increase the activity of the Elk1 reporter but did not show an additive effect when coadministered to cells with EGF (Fig. 4B). We also observed that U0126 can inhibit all of the observed Elk1 activity in our system, regardless of treatment. Thus, the SCFAs under investigation can be divided into two distinct classes, those that can potentiate EGF-mediated MAPK activation on the Elk1 reporter, and those compounds that have no effect on EGF-stimulated Elk1 activity.

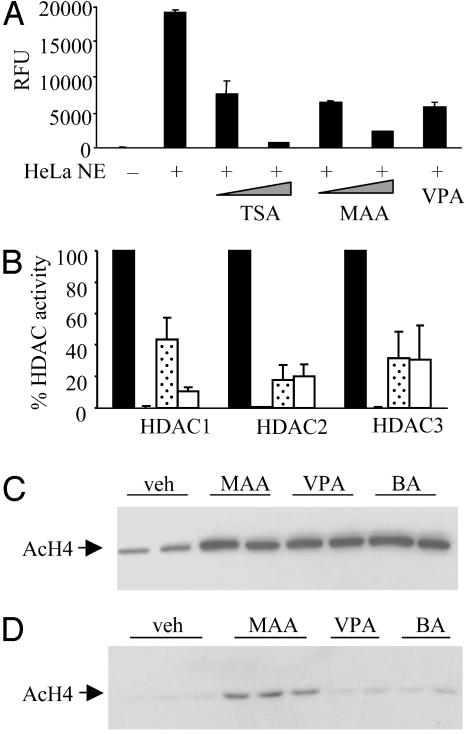

MAA Can Inhibit Endogenous HDAC Activity and Increase Histone Acetylation in Vitro and in Vivo. Based on the structural and functional similarity between MAA, VPA, and BA, and based on the reported HDAC inhibitory activities of VPA and BA, we tested the ability of MAA to inhibit HDAC activity. In HeLa cell nuclear extracts, MAA at 5 mM effectively inhibited endogenous HeLa HDAC activity (20% of vehicle control), whereas the potent HDAC inhibitor TSA inhibited the HDAC activity to 5% of vehicle control (Fig. 5A). A concentration of 2 mM VPA, which correlated to the highest nontoxic dose for our cell-based HeLa Elk1 reporter assay, inhibited HDAC activity to 30% of vehicle control (Fig. 5A). We next assessed the ability of these three compounds to inhibit immunoprecipitated, overexpressed class I HDACs. We observed complete inhibition of HDAC-1, HDAC-2, and HDAC-3 with TSA (Fig. 5B). Interestingly, whereas VPA and MAA were equally effective inhibitors of HDAC-2 and HDAC-3, we observed that MAA was a less effective inhibitor of HDAC-1.

Fig. 5.

MAA can inhibit endogenous or isolated HDAC activity and increase histone acetylation in vitro and in vivo. (A) HeLa cell nuclear protein extracts were incubated with vehicle, 5 nM or 1 μM TSA, 1 mM or 5 mM MAA, or 2 mM VPA for 45 min. HDAC activities are presented as averages of duplicate samples ± SD. (B) Immunoprecipitated HDACs were incubated with vehicle, 1 μM TSA, 5 mM MAA, or 2 mM VPA for 45 min, and the HDAC activities are presented as 100% HDAC activity. Data are presented as the averages of three separate experiments ± SD. (C) HeLa cells were treated with vehicle, 5 mM MAA, 2 mM VPA, and 5 mM BA for 24 h. Histones were analyzed by SDS/PAGE and were probed with an antibody to acetylated histone H4 (AcH4). (D) C57BL/6 mice treated as described in Supporting Materials and Methods and histones from the spleens were analyzed as in C. Data are representative of n = 8 for each treatment group.

To determine the effects of MAA-mediated HDAC inhibition on endogenous histone acetylation, we isolated bulk histones from HeLa cells for Western blot analyses. In cells treated with MAA, VPA, or BA, we observed a 3-fold increase in the acetylated form of histone H4 compared with vehicle-treated cells (Fig. 5C). To address the comparative HDAC inhibition properties of the SCFAs in vivo, we collected histone samples from the spleens of treated mice. Two hours after injection of compound, animals that were administered MAA showed a marked increase in the levels of acetylated histone H4 over that of vehicle-treated animals (Fig. 5D). Interestingly, the levels of acetylated histone H4 from the spleens of VPA- or BA-treated animals were comparable with the levels present in vehicle-treated animals. Similar acetylation patterns of histone H4 were observed in the hippocampi of mice treated with SCFAs (M.S.J., P.J.M., and D.P.M., unpublished data). These results correlate with previous observations that VPA has rapid clearance in rodents and that BA has a 6-min serum half-life (25, 26). We conclude that MAA may exhibit higher bioavailability and/or is likely to possess different HDAC inhibition activity compared with other SCFAs.

Discussion

In this study, we demonstrate that the SCFAs MAA and VPA can potentiate the transcriptional efficacy of several ligand-activated NRs by functioning as activators of MAPK and by inhibiting HDAC activity. Given that the MAA-dependent effects on NR signaling can be blocked by MEK1/2 inhibitors, our results strongly suggest that aspects of MAA action occur upstream of NRs, although in a manner that amplifies its effect on NR transcriptional activity. Previously, MAPK activation has been linked to phosphorylation of ER and PR (17, 27, 28). However, one of the most likely points of convergence of NR and MAPK signaling is at the level of coactivators (29). Indeed, a recent study (30) demonstrated that MAPK-mediated enhancement of ER-transcriptional activity correlates with the degree of hyperphosphorylation of the coactivator SRC-3/AIB-1. We propose that the relative contributions of MAPK activation and HDAC inhibition for each SCFA are different, possibly explaining the selectivity observed in our studies. The next objective of our mechanistic studies is to identify the targets of MAPK and HDAC, whose modifications can explain the enhanced efficacy of ligand-activated NRs.

Cumulatively, our findings suggest that individuals who are exposed to these xenobiotic SCFAs are more likely to experience untoward side effects on administration of exogenous estrogens and progestins. A particular concern in this regard is the prevalence of occupational exposure to EGME/MAA in the semiconductor and painting industries, which has been associated with anovulation, spontaneous abortion, and spermatocyte depletion (31, 32). Reports have estimated that 130,000 workers in the U.S. were potentially exposed to EGME between the years of 1981–1983 and that EGME production in 1991 was estimated at 80 million lb per year (33). Likewise, VPA elicits a range of endocrine disrupting activities, including anovulation and polycystic ovaries (34, 35). VPA, as Depakote (Abbott Laboratories), has been included on the list of the top 100 prescriptions for the number of U.S. prescriptions dispensed. Consequently, we propose that exposure to MAA and VPA should be considered before an individual receives exogenous sex steroids for oral contraception or for the treatment of menopausal symptoms. Our data suggest that coadministered VPA or exposure to MAA in combination with HT regimens may precipitate a previously unrecognized drug–drug interaction.

In conclusion, the identification of chemicals that impact cell signaling pathways and an understanding of the phenotypic consequences of these manipulations will facilitate an assessment of disease risk and may aid in the development of improved therapeutics. Notably, proposed endocrine disruptor screening programs focus on the identification of hormone-mimetics as a first line screen (36), an approach that would not recognize MAA and VPA. Our findings highlight a clear need to establish assays that would identify additional hormone sensitizers. Importantly, the duration of exposure to estrogens, progestins, and androgens is associated with increased risks of breast, ovarian, and prostate cancers. As emphasized by our study, we must now consider how each individual's response to hormones or drugs that target the sex steroid receptors are influenced by exposure to environmental and pharmacological modifiers such as MAA and VPA.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Drs. Ken Korach, Channing Der, Stephen Safe, Patrick Casey, and Tso-Pang Yao for their helpful discussions; Jeff Tucker for technical assistance and for printing the microarrays; Jennifer Collins for assistance in compiling the microarray data; and Drs. Carlos Suarez-Quian and Francina Munell for bringing to our attention the toxicology of EGME/MAA. This work was supported by National Institutes of Health Grants DK48807 and CA90645 (to D.P.M.) and CA92984 (to M.S.J.).

Abbreviations: SCFA, short-chain fatty acid; NR, nuclear receptor; HT, hormone therapy; ER, estrogen receptor; PR, progesterone receptor; MAA, methoxyacetic acid; VPA, valproic acid; VPD, valpromide; BA, butyric acid; EGME, ethylene glycol monomethyl ether; MAPK, mitogen-activated protein kinase; HDAC, histone deacetylase; ERK, extracellular signal-regulated kinase; TSA, trichostatin A; ERE, estrogen-response element, 3× ERE, three copies of a consensus ERE; EGF, epidermal growth factor.

References

- 1.Rattenborg, T., Gjermandsen, I. & Bonefeld-Jorgensen, E. C. (2002) Breast Cancer Res. 4, R12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hoyer, P. B. (2001) Biochem. Pharmacol. 62, 1557-1564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rossouw, J. E., Anderson, G. L., Prentice, R. L., LaCroix, A. Z., Kooperberg, C., Stefanick, M. L., Jackson, R. D., Beresford, S. A., Howard, B. V., Johnson, K. C., et al. (2002) J. Am. Med. Assoc. 288, 321-333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hulley, S., Grady, D., Bush, T., Furberg, C., Herrington, D., Riggs, B. & Vittinghoff, E. (1998) J. Am. Med. Assoc. 280, 605-613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Herrington, D. M., Howard, T. D., Hawkins, G. A., Reboussin, D. M., Xu, J., Zheng, S. L., Brosnihan, K. B., Meyers, D. A. & Bleecker, E. R. (2002) N. Engl. J. Med. 346, 967-974. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.McDonnell, D. & Norris, J. (2002) Science 296, 1642-1644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Weigel, N. L. (1996) Biochem. J. 319, 657-667. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chang, C.-Y., Norris, J. D., Gron, H., Paige, L. A., Hamilton, P. T., Kenan, D. J., Fowlkes, D. & McDonnell, D. P. (1999) Mol. Cell. Biol. 19, 8226-8239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Norris, J., Fan, D., Aleman, C., Marks, J. R., Futreal, A., Wiseman, R. W., Iglehart, J. D., Deininger, P. L. & McDonnell, D. P. (1995) J. Biol. Chem. 270, 22777-22782. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ganesan, S., Jansen, M. S., Nagel, S. C., Cook, C. E. & McDonnell, D. P. (2002) Endocrinology 143, 3071-3082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Brinkworth, M. H., Weinbauer, G. F., Schlatt, S. & Nieschlag, E. (1995) J. Reprod. Fertil. 105, 25-33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Almekinder, J. L., Lennard, D. E., Walmer, D. K. & Davis, B. J. (1997) Fundam. Appl. Toxicol. 38, 191-194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Terry, K. K., Elswick, B. A., Stedman, D. B. & Welsch, F. (1994) Teratology 49, 218-227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Shih, T. S., Liou, S. H., Chen, C. Y. & Smith, T. J. (2001) Arch. Environ. Health 56, 20-25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Di Lorenzo, D., Albertini, A. & Zava, D. (1991) Cancer Res. 51, 4470-4475. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zhu, L. J., Cullinan-Bove, K., Polihronis, M., Bagchi, M. K. & Bagchi, I. C. (1998) Endocrinology 139, 3923-3934. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Shen, T., Horwitz, K. B. & Lange, C. A. (2001) Mol. Cell. Biol. 21, 6122-6131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Labriola, L., Salatino, M., Proietti, C. J., Pecci, A., Coso, O. A., Kornblihtt, A. R., Charreau, E. H. & Elizalde, P. V. (2003) Mol. Cell. Biol. 23, 1095-1111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Martin, M. B., Franke, T. F., Stoica, G. E., Chambon, P., Katzenellenbogen, B. S., Stoica, B. A., McLemore, M. S., Olivo, S. E. & Stoica, A. (2000) Endocrinology 141, 4503-45011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Topping, D. L. & Clifton, P. M. (2001) Physiol. Rev. 81, 1031-1064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Phiel, C. J., Zhang, F., Huang, E. Y., Guenther, M. G., Lazar, M. A. & Klein, P. S. (2001) J. Biol. Chem. 276, 36734-36741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Warrell, R. P. J., He, L. Z., Richon, V., Calleja, E. & Pandolfi, P. P. (1998) J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 90, 1621-1625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Blaheta, R. A. & Cinatl, J. J. (2002) Med. Res. Rev. 22, 492-511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yuan, P.-X., Huang, L.-D., Jiang, Y.-M., Gutkind, S., Manji, H. K. & Chen, G. (2001) J. Biol. Chem. 276, 31674-31683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Summer, C. J., Huynh, T. N., Markowitz, B. S., Perhac, S., Hill, B., Coovert, D. D., Schussler, K., Chen, X., Jarecki, J., Burghes, A. H. M., et al. (2003) Ann. Neurol. 54, 647-654. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Brichta, L., Hofmann, Y., Hahnen, E., Siebzehnrubl, F. A., Raschke, H., Blumcke, I., Eyupoglu, I. Y. & Wirth, B. (2003) Hum. Mol. Genet. 12, 2481-2489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kato, S., Endoh, H., Masuhiro, Y., Kitamoto, T., Uchiyama, S., Sasaki, H., Masushige, S., Gotoh, Y., Nishida, E., Kawashima, H., et al. (1995) Science 270, 1491-1494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lee, H., Jiang, F., Wang, Q., Nicosia, S. V., Yang, J., Su, B. & Bai, W. (2000) Mol. Endocrinol. 14, 1882-1896. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rowan, B. G., Weigel, N. L. & O'Malley, B. W. (2000) J. Biol. Chem. 275, 4475-4483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Font de Mora, J. & Brown, M. (2000) Mol. Cell. Biol. 20, 5041-5047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Correa, A., Gray, R., Cohen, R., Rothman, N., Shah, F., Seacat, H. & Corn, M. (1996) Am. J. Epidemiol. 143, 707-717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.El-Zein, R. A., Abdel-Rahman, S. Z., Morris, D. L. & Legator, M. S. (2002) Arch. Environ. Health 57, 371-376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health. (1991) Occupational Exposure to Ethylene Glycol Monomethyl Ether, Ethylene Glycol Monoethyl Ether, and Their Acetates, (Natl. Inst. Health, Bethesda), DHHS Publ. No. (NIH) 91-119.

- 34.Isojarvi, J. I., Laatikainen, T. J., Knip, M., Pakarinen, A. J., Juntunen, K. T. & Myllyla, V. V. (1996) Ann. Neurol. 39, 579-584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Isojarvi, J. I., Tauboll, E., Pakarinen, A. J., van Parys, J., Rattya, J., Harbo, H. F., Dale, P. O., Fauser, B. C., Gjerstad, L., Koivunen, R., et al. (2001) Am. J. Med. 111, 290-296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Environmental Protection Agency (1998) Federal Register 63, 71541-71568. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.