Abstract

Rice (Oryza sativa L.) can produce black grains as well as white. In black rice, the pericarp of the grain accumulates anthocyanin, which has antioxidant activity and is beneficial to human health. We developed a black rice introgression line in the genetic background of Oryza sativa L. ‘Koshihikari’, which is a leading variety in Japan. We used Oryza sativa L. ‘Hong Xie Nuo’ as the donor parent and backcrossed with ‘Koshihikari’ four times, resulting in a near isogenic line (NIL) for black grains. A whole genome survey of the introgression line using DNA markers suggested that three regions, on chromosomes 1, 3 and 4 are associated with black pigmentation. The locus on chromosome 3 has not been identified previously. A mapping analysis with 546 F2 plants derived from a cross between the black rice NIL and ‘Koshihikari’ was evaluated. The results indicated that all three loci are essential for black pigmentation. We named these loci Kala1, Kala3 and Kala4. The black rice NIL was evaluated for eating quality and general agronomic traits. The eating quality was greatly superior to that of ‘Okunomurasaki’, an existing black rice variety. The isogenicity of the black rice NIL to ‘Koshihikari’ was very high.

Keywords: black rice, Kala, ‘Koshihikari’, ‘Hong Xie Nuo’, mapping, near isogenic line, Oryza sativa L.

Introduction

Rice (Oryza sativa L.) is one of the most important cereal crops in the world. Most rice cultivars produce grains with white pericarps, but some have colored pericarps, which can be red, brown, or black (also known as purple). The pericarps of colored rice grains accumulate proanthocyanidin (“red rice”) or anthocyanin (“black rice”). These proanthocyanidins and anthocyanins have antioxidant activity and their health benefits have been demonstrated not only in rice but also in soy bean, potato, and sweet potato (Hou et al. 2010, Jang et al. 2010, Kaspar et al. 2011, Kawasaki et al. 2007, Kwon et al. 2007, Ling et al. 2001, Suda et al. 2008). Since rice is a staple food for many consumers around the world, we expect that the introduction of colored rice could have a greater global health impact than the introduction of other foods containing proanthocyanidins and anthocyanins.

In Japan, black rice varieties have been bred with improvements in traits related to cultivation (for example lodging resistance and early maturing) and several cultivars have already been released (Higashi et al. 1997, Saka et al. 2007, Takita et al. 2001). However, black rice varieties with improved eating quality have not yet been developed. The most widely produced rice cultivar in Japan is ‘Koshihikari’, because of its palatability and good viscosity when boiled. One approach to developing new cultivars with superior eating quality is to develop near isogenic lines (NILs) with novel agronomic traits in the genetic background of ‘Koshihikari’ (Kojima et al. 2004, Takeuchi et al. 2006, Wan et al. 2005). An effective tool in the development of NILs is marker-assisted selection, in which DNA markers are used to identify plants carrying desired traits. Several rice varieties have been developed by marker-assisted selection in the last decade (Ebitani et al. 2011, Ishimaru et al. 2013, Ookawa et al. 2010, Saka et al. 2010, Takeuchi et al. 2006).

Our goal was to develop a novel rice variety with a black pericarp in the ‘Koshihikari’ genetic background. For this purpose we could not use marker-assisted selection, because genetic markers associated with loci responsible for anthocyanin production in the pericarp had not been identified. Classical genetics indicated that two genes, PURPLE PERICARP B (Pb) located on chromosome 4 and PURPLE PERICARP A (Pp) located on chromosome 1, were required for black pigmentation (Causse et al. 1994, Yoshimura et al. 1997). However, these genes have not been mapped well enough to identify nearby DNA markers. Therefore, we made an initial cross between the black-grained variety ‘Hong Xie Nuo’ and the popular edible variety ‘Koshihikari’, and then used phenotype selection in backcrosses with ‘Koshihikari’. After four backcrosses we performed a whole genome survey using DNA markers covering the rice genome. The results suggested that a region on chromosome 3, in addition to regions on chromosomes 1 and 4, might be associated with black pigmentation of the pericarp. This is the first report of a gene locus on chromosome 3 being associated with black pigmentation in the pericarp.

In this paper we describe the development of a black rice NIL in the ‘Koshihikari’ genetic background. The line has three introgression fragments from the black rice donor parent ‘Hong Xie Nuo’. Furthermore, we performed a genetic analysis of black pigmentation in the pericarp and examined various eating quality and agronomic traits of the black rice NIL.

Materials and Methods

Plant materials and development of the NIL

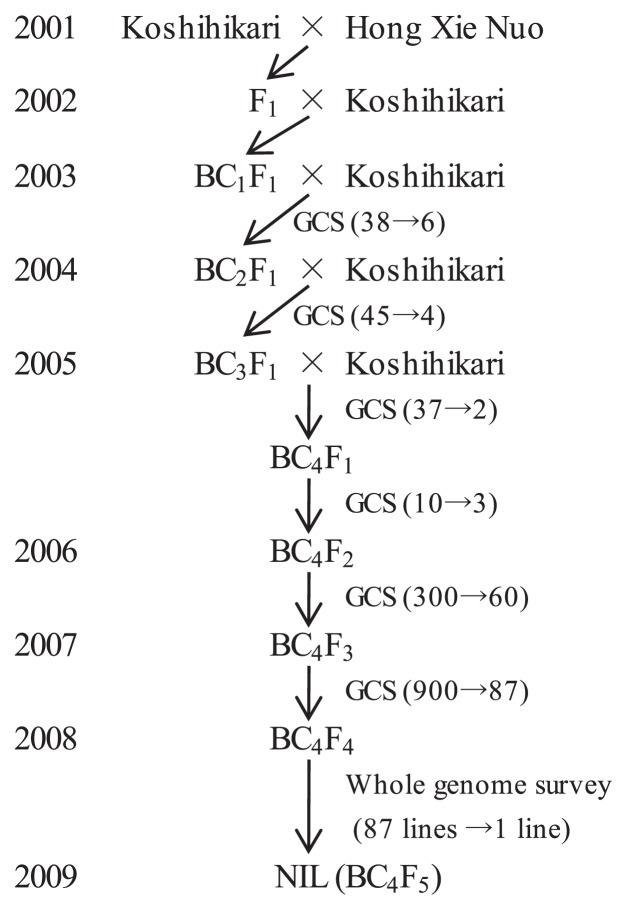

The process we used to produce the black rice NIL is shown in Fig. 1. ‘Koshihikari’ (with white grains) was crossed as a female parent with ‘Hong Xie Nuo’ (black grains); the grain colors are shown in Supplemental Fig. 1. A resultant F1 plant was backcrossed to ‘Koshihikari’ to produce the BC1 line. Each of 38 BC1F1 plants was both selfed and backcrossed with ‘Koshihikari’ the following summer (2003). Grain color selection (GCS) was used to identify which BC1F1 progeny would be used in further crosses. The self progeny of the BC1F1 plants were grown in the autumn and those with colored pericarps identified. Six BC1F1 lines were selected, and a total of 45 BC2F1 seeds were harvested from these lines. The same GCS method was used to select the BC2F1, BC3F1 and BC4F1 plants whose progeny were used in further crosses (see Fig. 1). Three of 10 BC4F1 plants produced self-progeny with colored grains, and the BC4F2 seeds from these plants were harvested. A total of 300 BC4F2 plants were raised, and of these, 60 produced colored grains. In the same way, 87 lines were selected from 900 BC4F3 plants. The BC4F4 plants derived from these 87 BC4F3 plants were raised, and a single BC4F4 line (no. 1 in Supplemental Fig. 2) was selected as the black rice NIL based on its phenotype and the results of a whole genome survey with 130 simple sequence repeat (SSR) markers (see below). The black rice NIL was self-pollinated to get BC4F5 seeds. The 87 BC4F4 lines were also used for the fine mapping of a locus on chromosome 3 that we found to be associated with black pigmentation in the pericarp.

Fig. 1.

Breeding of the black rice NIL. GCS: grain color selection. Numbers in parentheses indicate the total number of plants in each generation and the number selected for backcrossing or selfing.

The black rice NIL was crossed with ‘Koshihikari’ and 542 F2 progeny were used as a mapping population to examine the contributions of the three loci (on chromosomes 1, 3 and 4) toward black pigmentation in the pericarp.

In order to evaluate the eating quality of the black rice NIL, we compared eating quality-related traits between the NIL, ‘Koshihikari’, and Oryza sativa L. ‘Okunomurasaki’, which is a widely cultivated black rice variety in Japan.

Evaluation of phenotypes

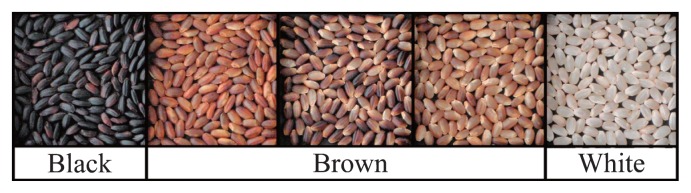

Plant materials were cultivated in a paddy field at Toyama Prefectural Agricultural, Forestry & Fisheries Research Center (TAFFRC). Grain color was classified visually into three types: black, brown and white (Fig. 2). The brown color could be further classified into three subgroups: brown, partial brown, and light brown; however for genetic analyses only the three main categories were used. Twenty plants in each of the 87 lines were evaluated for grain color.

Fig. 2.

Grain color classification. Three colors, black, brown, and white, were used in the genetic analyses. However, the brown category could be sub-classified into three colors: brown, partial brown, and light brown.

Analyses of protein content, amylose content, and pasting properties of the rice flours, (traits related to eating quality) were carried out according to Yamamoto et al. (1996). The pasting properties were investigated using a Rapid Visco Analyser (Newport Scientific, Warriewood, NSW, Australia). Two viscosity parameters, breakdown viscosity and consistency viscosity, were obtained from the pasting curve. Twenty panels were used to evaluate eating quality. Rice grains milled to 95% of their weight were used for sensory evaluation. ‘Okunomurasaki’ was used as a blind control and the quality of the NIL was compared with that of the control. Eating qualities, including an overall evaluation, stickiness, hardness, and glossiness, were classified into nine levels (−2: especially bad to +2: excellent). Antioxidant activity was evaluated using the chemiluminescence method of Kimura et al. (1999). The isogenicity of the black rice NIL to ‘Koshihikari’ was evaluated using several agricultural traits including heading date, culm length, panicle length, panicle number, and grain yield.

DNA marker analysis

A total of 130 SSR markers covering all 12 chromosomes were used for mapping genotypes in the 87 BC4F4 lines (Supplemental Fig. 2). These SSR markers were developed by McCouch et al. (2002) or the International Rice Genome Sequencing Project (2005). Genomic DNA was extracted from leaves using the CTAB method (Murray and Thompson 1980) and used in the polymerase chain reaction (PCR). PCR amplification was performed in a 10 μl reaction volume containing 10–100 ng genomic DNA, 0.2 μM primers, 1 x PCR buffer, 1.5 mM MgCl2, 0.2 mM each dNTP and 0.1 μl Taq DNA polymerase (5 U/μl). Thermal cycling consisted of an initial denaturation at 95°C for 2 min followed by 35 cycles of 95°C for 30 sec, 55°C for 30 sec, 72°C for 1 min, and a final extension at 72°C for 3 min. To detect polymorphisms, the amplified products were electrophoresed on 3% agarose gels.

For the analysis of the 542 F2 progeny from the cross between the black rice NIL and ‘Koshihikari’, genomic DNA was extracted from leaves using the single-step protocol (Thomson and Henry 1995). A 1.5 μl aliquot of this DNA extract was used as the template for PCR amplification. Thermal cycling was carried out as described above. For this analysis, the genotypes of the three loci on chromosomes 1, 3, and 4 were determined using the SSR markers RM8129, RM15191, and RM2441, respectively.

Results

Development of the black rice NIL

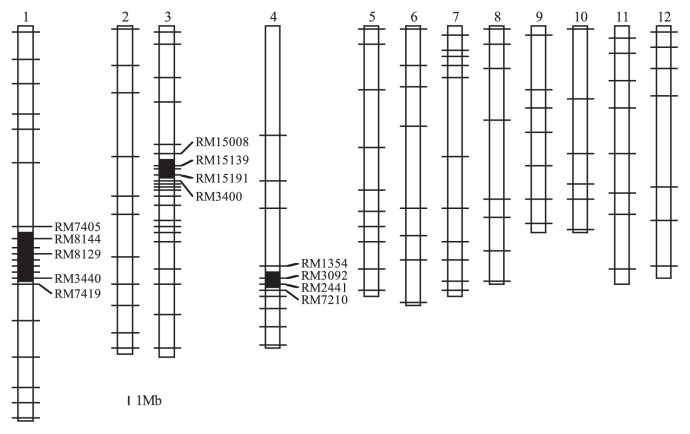

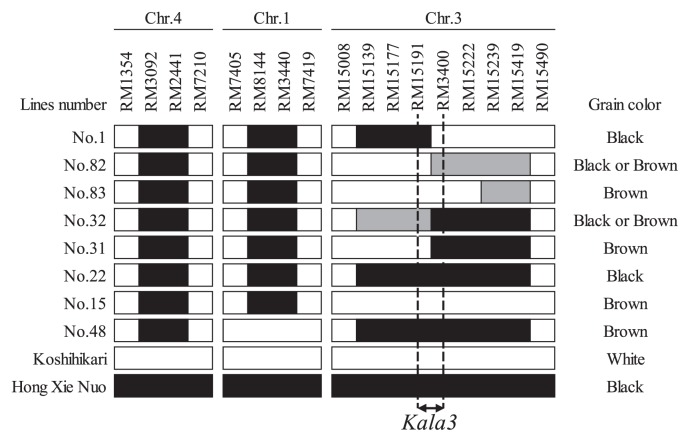

After crossing ‘Koshihikari’ (white grains) with ‘Hong Xie Nuo’ (black grains) and then backcrossing to ‘Koshihikari’ (see Methods and Fig. 1), we evaluated the genotypes and grain colors of 87 BC4F4 lines (Supplemental Fig. 2). Based on an analysis with 130 SSR markers, we found that all lines had a homozygous segment derived from ‘Hong Xie Nuo’ on chromosome 4 and produced colored grains. Lines that also had homozygous regions derived from ‘Hong Xie Nuo’ on both chromosomes 1 and 3 produced black grains. We selected one line (no. 1 in Supplemental Fig. 2) that produced only black grains and that was mainly homozygous for ‘Koshihikari’ alleles. This line had three chromosome segments derived from ‘Hong Xie Nuo’ on chromosomes 1, 3 and 4 in the genetic background of ‘Koshihikari’. Based on the Rice Annotation Project Database (RAP-DB, http://rapdb.dna.affrc.go.jp/), the physical sizes of these segments were 5.8 Mbp (between the markers RM7405 and RM7419) on chromosome 1, 3.0 Mbp (between RM15008 and RM3400) on chromosome 3, and 2.3 Mbp (between RM1354 and RM7210) on chromosome 4 (Fig. 3). The pigmented tissues in this black rice NIL were only the pericarp and the stigma; other tissues, including the leaf blade, sheath, ligule, stem node, and apiculus showed normal green coloring.

Fig. 3.

Graphical representation of the NIL genotype. Black and white regions indicate regions homozygous for ‘Hong Xie Nuo’ alleles and ‘Koshihikari’ alleles, respectively. Horizontal bars indicate the positions of 130 SSR markers. The maps are scaled on the basis of physical distances.

Validation of three loci for black pigmentation

To understand the contribution of each of the three chromosomal segments toward black pigmentation of the pericarp, we analyzed an F2 population (542 plants) derived from a cross between the black rice NIL and ‘Koshihikari’. The population segregated into a colored group (397 plants) and a white group (145 plants), and the segregation ratio showed a good fit to the 3 : 1 ratio typical of a gene with one dominant and one recessive allele (χ2 = 0.89, P > 0.05). Among the 397 colored plants, the genotypes for RM8129 (a marker within the chromosome 1 segment) segregated 105 (‘Hong Xie Nuo’ homozygous) : 178 (heterozygous) : 114 (‘Koshihikari’ homozygous) and this fitted the 1 : 2 : 1 segregation pattern (χ2 = 4.64, P > 0.05, Table 1). Similarly, the genotypes for RM15191 (within the chromosome 3 segment) segregated 82 : 200 : 115, and this also fitted the 1 : 2 : 1 segregation pattern (χ2 = 5.51, P > 0.05, Table 1). On the other hand, the genotypes for RM2441 (in the chromosome 4 segment) segregated 116 : 274 : 7, and this clearly did not fit the 1 : 2 : 1 segregation pattern (χ2 = 117.0, P < 0.001, Table 1). In the white group of 145 plants, the genotypes for RM8129 and RM15191 each segregated to fit the 1 : 2 : 1 segregation pattern but the genotypes for RM2441 did not. Thus, only RM2441 showed segregation distortion. We concluded that an allele derived from ‘Hong Xie Nuo’ on chromosome 4 is necessary for pericarp pigmentation.

Table 1.

Segregation of grain colors in an F2 population derived from a cross between the black rice NIL and ‘Koshihikari’

| Marker Name (Chromosome) | Colored (Black and Brown) | White | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|||||||||

| No. of genotypesa | χ2 b (1 : 2 : 1) | No. of genotypesa | χ2 b (1 : 2 : 1) | |||||||

|

|

|

|||||||||

| Kk | H | Ks | Total | Kk | H | Ks | Total | |||

| RM8129 (1) | 105 | 178 | 114 | 397 | 4.64 | 29 | 75 | 41 | 145 | 2.16 |

| RM15191 (3) | 82 | 200 | 115 | 397 | 5.51 | 26 | 83 | 36 | 145 | 4.42 |

| RM2441 (4) | 116 | 274 | 7 | 397 | 117*** | 0 | 1 | 144 | 145 | 427*** |

Genotypes Kk, Ks, and H are homozygous for the ‘Hong Xie Nuo’ allele, homozygous for the ‘Koshihikari’ allele, and heterozygous, respectively.

P < 0.001.

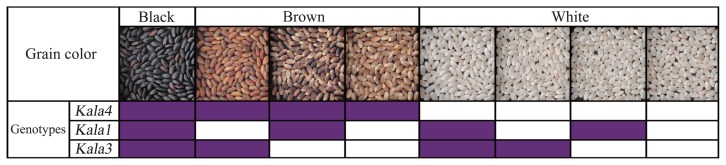

Of the 397 colored plants, 32 had chromosomal regions that were homozygous for either the ‘Hong Xie Nuo’ alleles or the ‘Koshihikari’ alleles at the three chromosomal regions. These 32 plants were classified on the basis of genotypes and grain colors (Table 2). Only plants that had homozygous ‘Hong Xie Nuo’ segments on chromosomes 1, 3 and 4 produced black grains. Plants that had ‘Koshihikari’ segments on either chromosome 1 or chromosome 3 produced only brown grains (Table 2). Thus it was revealed that the ‘Hong Xie Nuo’ alleles on chromosomes 1 and 3 are necessary for black pigmentation of the rice pericarp.

Table 2.

Association of Kala1 and Kala3 genotypes with grain color in plants possessing colored grains

| Genotypesa | Number of plants | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|||

| Kala4 | Kala1 | Kala3 | Black | Brown |

| Kk | Kk | Kk | 7 | 0 |

| Ks | 0 | 10 | ||

|

| ||||

| Ks | Kk | 0 | 7 | |

| Ks | 0 | 8 | ||

Genotypes Kk and Ks are homozygous for the ‘Hong Xie Nuo’ allele and the ‘Koshihikari’ allele, respectively.

Based on the above results, we confirmed that three loci on chromosomes 1, 3 and 4 together confer black pigmentation on the rice pericarp. We named these loci Key gene for black coloration by anthocyanin accumulation on chromosome 1, 3, and 4 (Kala1, Kala3 and Kala4). Based on the lengths of the substituted ‘Hong Xie Nuo’ chromosomal segments, Kala1, Kala3, and Kala4 mapped between RM7405 and RM7419 on chromosome 1, between RM15008 and RM3400 on chromosome 3, and between RM1354 and RM7210 on chromosome 4, respectively.

Fine mapping of Kala3

Among the 87 BC4F4, lines the lengths of the substituted segments on chromosome 3 varied (see no. 1, 15, 22, 31, 32, 48, 82 and 83 in Supplemental Fig. 2). These lines were used for substitution mapping of Kala3. The results indicated that Kala3 is located in a region of 516 kbp between RM15191 and RM3400 (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4.

Fine mapping of Kala3. The black, white and gray regions indicate regions homozygous for ‘Hong Xie Nuo’, homozygous for ‘Koshihikari’, and heterozygous, respectively.

Grain color phenotypes conferred by various combinations of Kala1, Kala3, and Kala4

We identified individual plants among the mapping F2 population that were homozygous for either the ‘Koshihikari’ or the ‘Hong Xie Nuo’ alleles at each of the three loci, Kala1, Kala3, and Kala4. As indicated above, only plants that carried the ‘Hong Xie Nuo’ alleles at all three loci produced black grains (Fig. 5). Brown grains of various shades were produced by plants with ‘Hong Xie Nuo’ alleles at Kala4 and ‘Koshihikari’ alleles at one or both of the other two loci: with ‘Koshihikari’ alleles at Kala1 and Kala3, the grains were light brown; with ‘Koshihikari’ alleles only at Kala3, the grains were partial brown; and with ‘Koshihikari’ alleles only at Kala1, the grains were brown. In plants that carried ‘Koshihikari’ alleles at Kala4, the grains were white, regardless of the genotypes at the other two loci (Fig. 5).

Fig. 5.

Patterns of the grain color defined by three loci, Kala1, Kala3, and Kala4. The purple and white boxes indicate ‘Hong Xie Nuo’ alleles and ‘Koshihikari’ alleles, respectively.

Eating quality, antioxidant activity, and agricultural traits of the black rice NIL

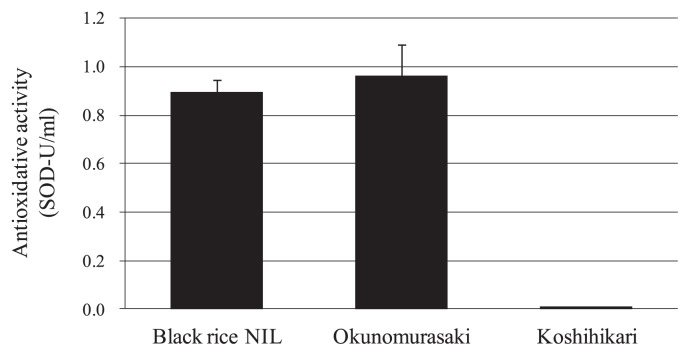

Traits related to eating quality, including protein content, amylose content, breakdown viscosity, and consistency viscosity were compared between the black rice NIL, ‘Koshihikari’, and ‘Okunomurasaki’. No significant differences were detected in any of the traits, however in each case the black rice NIL showed a value that was intermediate between those of ‘Koshihikari’ and ‘Okunomurasaki’ (Table 3). The eating qualities of the black rice NIL, in particular the overall evaluation and the glossiness, were greatly superior to those of ‘Okunomurasaki’. However, it was not possible to compare the eating qualities of the black rice varieties with those of ‘Koshihikari’ because of flavor differences. The antioxidant activity of the black rice NIL was much higher than that of ‘Koshihikari’ and similar to that of ‘Okunomurasaki’ (Fig. 6). Most of the agricultural traits of the black rice NIL were comparable with those of ‘Koshihikari’ (Supplemental Table 1). The black rice NIL headed two days later than ‘Koshihikari’ and had slightly lower yields in both 1000-grain weights and gross yield per acre.

Table 3.

Eating qualities and related traits in the black rice NIL

| Varieties | Grain color | Protein content (%) | Amylose content (%) | Pasting properties | Eating qualitiesa | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

||||||||

| Breakdown viscosity (RVU) | Consistency viscosity (RVU) | Overall evaluation | Stickness | Hardness | Glossiness | ||||

| Black rice NIL | Black | 5.9 | 14.3 | 165 | 104 | 0.34** | 0.28 | 0.14 | 0.22** |

| 0.17** | 0.05 | −0.20* | 0.44** | ||||||

| ‘Koshihikari’ | White | 5.7 | 14.1 | 198 | 115 | – | – | – | – |

| ‘Okunomurasaki’ | Black | 6.3 | 14.5 | 118 | 131 | 0.09 | 0.08 | 0.03 | 0.04 |

| 0.08 | 0.01 | 0.05 | −0.04 | ||||||

The upper and lower values for eating qualities were obtained in 2010 and 2011, respectively.

indicate that the differences between 2010 and 2011 were significant at P < 0.05 and P < 0.01, respectively.

Fig. 6.

Comparison of antioxidative activities between the black rice NIL, ‘Koshihikari’, and ‘Okunomurasaki’.

Discussion

In this study involving a whole genome survey of 87 BC4F4 lines and a genetic analysis of 542 F2 plants, we identified three loci, Kala1, Kala3, and Kala4, that influence grain color. Table 4 summarizes the possible relationships between these three loci and genes and loci identified in previous studies of pigment production in rice. Previous studies of black pigmentation in the rice pericarp showed that two loci, Pp on chromosome 1 and Pb on chromosome 4, acted together to influence grain color. Grains were black in the presence of both alleles, brown in the presence of Pb and the absence of Pp, and white in the absence of Pb (Rahman et al. 2013, Wang and Shu 2007). On the other hand, we found that three loci influence black coloration of the rice grain in ‘Hong Xie Nuo’ (Tables 1, 2 and Supplemental Fig. 2). Like Pb, the ‘Hong Xie Nuo’ allele at Kala4 is essential for grain color, and both alleles map to a region between RM1354 and RM7210 on chromosome 4 (Fig. 3 and Wang and Shu 2007). These results strongly suggest that Pb is an allele of Kala4.

Table 4.

Possible relationships between three loci, Kala1, Kala3, and Kala4, and previously reported loci and genes

| Locus | Possible allelic locus (Reference) | Cloned or possible gene (Reference)a |

|---|---|---|

| Kala1 |

Pp (Wang and Shu 2007) |

|

|

Rd (Furukawa et al. 2006) |

DFR (Furukawa et al. 2006) |

|

|

A (Nagao and Takahashi 1963) |

||

| Kala3 |

P (Nagao and Takahashi 1963) |

MYB (Saitoh et al. 2004) (Gao et al. 2011) |

| Kala4 |

Pb (Wang and Shu 2007) |

|

|

Pl (Kinoshita and Maekawa 1986) |

bHLH (Sakamoto et al. 2001) |

|

|

C (Nagao and Takahashi 1963) |

The cloned gene DFR occurs at the Rd locus, and the cloned gene bHLH gene occurs at the Pl locus. In this study we infer that P is a MYB gene.

Kala1 mapped to the region between RM7405 and RM7419 on chromosome 1. However, it is not clear whether Pp is an allele of Kala1 because the Pp gene locus was not precisely mapped (Oryzabase, www.gramene.org). On the other hand, since the ‘Hong Xie Nuo’ alleles at Kala4 and Kala1 interact genetically in the same way that Pb and Pp do, it is possible that Pp is an allele of Kala1.

Aside from these loci on chromosomes 1 and 4, Kala3 is the first additional gene locus that has been found to influence rice pericarp color.

Based on the pigmentation model reviewed by Koes et al. (2005), dihydroflavonol reductase (DFR) is a widely conserved gene that encodes an enzyme involved in both the anthocyanin and the proanthocyanidin synthetic pathways. In addition, certain MYB, basic helix-loop-helix (bHLH), and WD40 proteins are transcription factors that can activate the DFR gene. Since the WD40 genes are highly conserved (reviewed by Koes et al. 2005), it was proposed that polymorphisms at three genetic loci, DFR, MYB, and HLH, may confer the deposition of anthocyanin or proanthocyanidin pigments in various plant tissues. The chromosomal region (between RM7405 and RM7419) of Kala1 contains the Rd locus, which has been identified as a DFR gene (Furukawa et al. 2006). In red rice, the Rd gene interacts with the Rc gene on chromosome 7 to produce red grains (Furukawa et al. 2006). Similarly, Kala1 interacts with Kala4 in the production of colored grains. Thus it appears likely that Kala1 is Rd/DFR, and that ‘Koshihikari’ has a defective allele at this locus.

The purple leaf (Pl) locus was detected on chromosome 4 by Kinoshita and Maekawa (1986). Sakamoto et al. (2001) found that the Pl gene encodes a bHLH protein and reported that among three Pl alleles (Pli, Plw and Plj), Plw confers pigmented pericarps. As we mentioned above, the Rc gene on chromosome 7 interacts with Rd on chromosome 1 in the production of red pericarps. Sweeney et al. (2006) revealed that the Rc gene encodes a bHLH protein. These results led us to speculate that Kala4 may also encode a bHLH protein, and that Kala4 may either be Pl or that the two genes, Kala4 and Pl, might be tandemly duplicated genes with distinct tissue-specific transcription patterns. Three genes registered in the RAP-DB, Os04t0557200-1, Os04t0557500-00, and Os04t0557800-00, are located in the chromosomal region containing Kala4 and have bHLH domains. We are currently conducting expression analyses and complementation tests to determine which of the three is Kala4. If our speculations regarding Kala1 and Kala4 are correct, it seems likely that Kala3 might be a MYB gene. The RAP-DB shows 45 genes within the region of Kala3 identified by fine mapping of the locus (Fig. 4). Of these, Os03t0410000-01 was annotated as similar to OsMYB3. Therefore, Kala3 may be OsMYB3. More fine mapping and expression analyses are underway to reveal the identity of Kala3.

Nagao and Takahashi (1963) demonstrated that three genes, Chromogen gene (C), Activator gene (A), and tissue-specific regulator gene (P) are required for anthocyanin pigmentation in various tissues. We propose that Kala4, Kala1, and Kala3 might correspond to C, A, and P, respectively. As shown in Fig 5, only plants with segments from ‘Hong Xie Nuo’ on both chromosomes 4 and 1 produced dark brown grains. The color of the dark brown grains in this paper is similar to that of the grains described as medium purple, in which anthocyanin was detected, by Rahman et al. (2013). These results suggest that Kala1 and Kala4 are necessary for anthocyanin synthesis and that Kala1 corresponds to A.

MYB domains have been related to tissue-specific coloration of rice in previous studies. For example, the Colorless like regulatory gene 1 (OsC1) on chromosome 6, which encodes a MYB family transcription factor, regulates anthocyanin production in the apiculus and sheath (Gao et al. 2011, Saitoh et al. 2004). Yamaguchi et al. (2011) developed a novel line “Tokei 1378,” which has a colored apiculus caused by expression of the OsC1 gene from Oryza sativa L. ‘Awaakamai’ in the ‘Koshihikari’ background. We made a cross between our black rice NIL and Tokei 1378 and found that in the F2 population, only plants having three substituted segments on chromosomes 4, 1 and 6 showed pigmentation in the leaf margin, sheath, and ligule (unpublished data). These results showed that the MYB gene functioned as a tissue-specific regulator. Together, our results suggest that Kala3 may be P.

The grain color of the black rice NIL was slightly different from that of ‘Hong Xie Nuo’ (Fig. 5 and Supplemental Fig. 1). Thus, ‘Koshihikari’ may carry an additional unknown allele that is involved in pericarp pigmentation and that is not present in the ‘Hong Xie Nuo’ genome. Further studies are needed to identify this additional genetic factor.

Our main purpose was to breed a black rice variety with good eating quality. We used an existing black rice variety, ‘Okunomurasaki’, as a control and found that the black rice NIL is greatly superior to ‘Okunomurasaki’ in eating quality (Table 3). We want to emphasize that our black rice NIL is the first variety that has been bred to harbor both good eating quality and black grain color. Traits related to eating quality, including protein content, amylose content, breakdown viscosity, and consistency viscosity, also tended to be better in the black rice NIL than in ‘Okunomurasaki’: the values for each of these traits were intermediate between those of ‘Okunomurasaki’ and those of ‘Koshihikari’. It is not clear why the related traits in the black rice NIL were not equal to those of ‘Koshihikari’. It is possible that the pigment composition in the pericarp directly influences these traits. These traits may also be influenced by genes in the substituted chromosomal regions.

The beneficial health effects due to the antioxidant activities of black rice varieties were demonstrated by Chiang et al. (2006), Hou et al. (2010), and Ling et al. (2001). Our black rice NIL, with high antioxidant activity and superior palatability, should provide beneficial health effects if included as a regular part of the diet. The isogenicity of the black rice NIL to ‘Koshihikari’ was very high apart from slight differences in heading date and yield (Supplemental Table 1). The reason for the difference in heading date remains unknown. Ji et al. (2012) also reported that a purple-pericarp line showed reduced yields, and they suggested that this may be due to a reduced sink size. The black rice NIL also had reduced grain thickness (data not shown). These differences may be caused by gene(s) related to sink size in the introgressed segment(s).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We thank Dr. Takeshi Izawa for comments on this manuscript.

Literature Cited

- Causse, M.A., Fulton, T.M., Cho, Y.G., Ahn, S.N., Chunwongse, J., Wu, K., Xiao, J., Yu, Z., Ronald, P.C., Harrington, S.E.et al. (1994) Saturated molecular map of the rice genome based on an interspecific backcross population. Genetics 138: 1251–1274 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chiang, A.N., Wu, H.L., Yeh, H.I., Chu, C.S., Lin, H.C. and Lee, W.C. (2006) Antioxidant effects of black rice extract through the induction of superoxide dismutase and catalase activities. Lipids 41: 797–803 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ebitani, T., Hayashi, N., Omoteno, M., Ozaki, H., Yano, M., Morikawa, M. and Fukuta, Y. (2011) Characterization of Pi13, a blast resistance gene that maps to chromosome 6 in indica rice (Oryza sativa L. variety, Kasalath). Breed. Sci. 61: 251–259 [Google Scholar]

- Furukawa, T., Maekawa, M., Oki, T., Suda, I., Iida, S., Shimada, H., Takamure, I. and Kadowaki, K. (2006) The Rc and Rd genes are involved in proanthocyanidin synthesis in rice pericarp. Plant J. 49: 91–102 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao, D., He, B., Zhou, Y. and Sun, L. (2011) Genetic and molecular analysis of a purple sheath somaclonal mutant in japonica rice. Plant Cell Rep. 30: 901–911 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Higashi, T., Yamaguchi, M., Oyamada, Z., Sunohara, Y., Kowata, H., Tamura, Y., Yokogami, N., Sasaki, T., Abe, S., Matsunaga, K.et al. (1997) Breeding of a purple grain glutionous rice cultivar “Asamurasaki”. Bull. Tohoku Natl. Agric. Exp. Stn. 92: 1–13 [Google Scholar]

- Hou, Z., Qin, P. and Ren, G. (2010) Effect of anthocyanin-rich extract from black rice (Oryza sativa L. Japonica) on chronically alcohol-induced liver damage in rats. J. Agric. Food Chem. 58: 3191–3196 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- International Rice Genome Sequencing Project (2005) The map-based sequence of the rice genome. Nature 436: 793–800 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ishimaru, K., Hirotsu, N., Madoka, Y., Murakami, N., Hara, N., Onodera, H., Kashiwagi, T., Ujiie, K., Shimizu, B., Onishi, A.et al. (2013) Loss of function of the IAA-glucose hydrolase gene TGW6 enhances rice grain weight and increases yield. Nat. Genet. 45: 707– 711 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jang, H., Ha, U.S., Kim, S.J., Yoon, B.I., Han, D.S., Yuk, S.M. and Kim, S.W. (2010) Anthocyanin extracted from black soybean reduces prostate weight and promotes apoptosis in the prostatic hyperplasia-induced rat model. J. Agric. Food Chem. 58: 12686–12691 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ji, Z.J., Wang, X.G., Zeng, Y.X., Ma, L.Y., Li, X.M., Lin, B.X. and Yang, C.D. (2012) Comparison of physiological and yield traits between purple- and white-pericarp rice using SLs. Breed. Sci. 62: 71–77 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawasaki, M., Sato, Y., Chida, M. and Hatakeyama, C. (2007) Effects of dietary purple rice on plasma and liver lipid levels in rats. Bull. Morioka Junior College Iwate Pref. Univ. 9: 63–68 [Google Scholar]

- Kaspar, K.L., Park, J.S., Brown, C.R., Mathison, B.D., Navarre, D.A. and Chew, B.P. (2011) Pigmented potato consumption alters oxidative stress and inflammatory damage in men. J. Nutr. 141: 108–111 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kimura, T., Funatsuki, W., Agatsuma, M., Yamagishi, K. and Shinmoto, H. (1999) The radical scavenging activity of buckwheat leaves. Tohoku Agric. Res. 52: 255–256 [Google Scholar]

- Kinoshita, T. and Maekawa, M. (1986) Genetical studies on rice plants. XCIV. Inheritance of purple leaf color found in indica rice. J. Fac. Agr. Hokkaido Univ. 62: 453–467 [Google Scholar]

- Koes, R., Verweij, W. and Quattrocchio, F. (2005) Flavonoids: a colorful model for the regulation and evolution of biochemical pathways. Trends Plant Sci. 10: 236–242 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kojima, Y., Ebitani, T., Yamamoto, Y. and Nagamine, T. (2004) Rice Blast: Interaction with Rice and Control. In: Kawasaki, S. (ed.) Kluwer Academic Publishers, Dordrecht, Netherlands, pp. 209–214 [Google Scholar]

- Kwon, S.H., Ahn, I.S., Kim, S.O., Kong, C.S., Chung, H.Y., Do, M.S. and Park, K.Y. (2007) Anti-obesity and hypolipidemic effects of black soybean anthocyanins. J. Med. Food 10: 552–556 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ling, W.H., Cheng, Q.X., Ma, J. and Wang, T. (2001) Red and black rice decrease atherosclerotic plaque formation and increase antioxidant status in rabbits. J. Nutr. 131: 1421–1426 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCouch, S.R., Teytelman, L., Xu, Y., Lobos, K.B., Clare, K., Walton, M., Fu, B., Maghirang, R., Li, Z., Xing, Y.et al. (2002) Development and mapping of 2240 new SSR markers for rice (Oryza sativa L.). DNA Res. 9: 199–207 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murray, M.G. and Thompson, W.F. (1980) Rapid isolation of high molecular weight plant DNA. Nucleic Acids Res. 8: 4321–4325 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nagao, S. and Takahashi, M. (1963) Genetical studies on rice plants. XXVII. Trial construction of twelve linkage groups in Japanese rice. J. Fac. Agri. Hokkaido Univ. 58: 72–130 [Google Scholar]

- Ookawa, T., Hobo, T., Yano, M., Murata, K., Ando, T., Miura, H., Asano, K., Ochiai, Y., Ikeda, M., Nishitani, R.et al. (2010) New approach for rice improvement using a pleiotropic QTL gene for lodging resistance and yield. Nat. Commun. 1: 132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rahman, M.M., Lee, K.E., Lee, E.S., Matin, M.N., Lee, D.S., Yun, J.S., Kim, J.B. and Kang, S.G. (2013) The genetic constitutions of complementary genes Pp and Pb determine the purple color variation in pericarps with cyaniding-3-O-glucoside depositions in black rice. J. Plant Biol. 56: 24–31 [Google Scholar]

- Saitoh, K., Onishi, K., Mikami, I., Thidar, K. and Sano, Y. (2004) Allelic diversification at the C (OsC1) locus of wild and cultivated rice: nucleotide changes associated with phenotypes. Genetics 168: 997–1007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saka, N., Terashima, T., Kudo, S., Kato, T., Sugiura, K., Endo, I., Shirota, M., Inoue, M. and Otake, T. (2007) A new purple grain glutinous rice variety “Minenomurasaki” for rice processing. Res. Bull. Aichi Agric. Res. Ctr. 39: 111–120 [Google Scholar]

- Saka, N., Fukuoka, S., Terashima, T., Kudo, S., Shirota, M., Ando, I., Sugiura, K., Sato, H., Maeda, H., Endo, I.et al. (2010) Breeding of a new variety “Chubu 125” with high field resistance for blast and excellent eating quality. Res. Bull. Aichi Agric. Res. Ctr. 42: 171–183 [Google Scholar]

- Sakamoto, W., Ohmori, T., Kageyama, K., Miyazaki, C., Saito, A., Murata, M., Noda, K. and Maekawa, M. (2001) The Purple leaf (Pl) locus of rice: the Plw allele has a complex organization and includes two genes encoding basic helix-loop-helix proteins involved in anthocyanin biosynthesis. Plant Cell Physiol. 42: 982–991 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suda, I., Ishikawa, F., Hatakeyama, M., Miyawaki, M., Kudo, T., Hirano, K., Ito, A., Yamakawa, O. and Horiuchi, S. (2008) Intake of purple sweet potato beverage affects on serum hepatic biomarker levels of healthy adult men with borderline hepatitis. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 62: 60–67 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sweeney, M.T., Thomsona, M.J., Pfeilb, B.E. and McCouch, S. (2006) Caught red-handed: Rc encodes a basic helix-loop-helix protein conditioning red pericarp in Rice. Plant Cell 18: 283–294 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takeuchi, Y., Ebitani, T., Yamamoto, T., Sato, H., Ohta, H., Hirabayashi, H., Kato, H., Ando, I., Nemoto, H., Imbe, T.et al. (2006) Development of isogenic lines of rice cultivar Koshihikari with early and late heading by marker-assisted selection. Breed. Sci. 56: 405–413 [Google Scholar]

- Takita, T., Higashi, T., Yamaguchi, M., Yokogami, N., Kataoka, T., Tamura, Y., Kowata, H., Oyamada, Z. and Sunohara, Y. (2001) Breeding of a new purple grain cultivar “Okuno-murasaki”. Bull. Tohoku Natl. Agric. Exp. Stn. 98: 1–10 [Google Scholar]

- Thomson, D. and Henry, R. (1995) Single-step protocol for preparation of plant tissue for analysis by PCR. Biotechniques 19: 394–400 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wan, Z.X., Sakaguchi, S., Oka, Y., Kitazawa, N. and Minobe, Y. (2005) Breeding of semi-dwarf Koshihikari by using genome breeding method. Breed. Res. 7 (Suppl. 1, 2): 217 [Google Scholar]

- Wang, G. and Shu, Q. (2007) Fine mapping and candidate gene analysis of purple pericarp gene Pb in rice (Oryza sativa L.). Chinese Science Bull. 52: 3097–3104 [Google Scholar]

- Yamaguchi, T., Maeda, H., Morikawa, M., Iyama, Y., Omoteno, M. and Ebitani, T. (2011) Development of a near isogenic rice line “Toyama-aka 78”, possessing of red pericarp and red apiculus with genetic background of “Koshihikari”. Breed. Res. 13 (Suppl. 1): 80 [Google Scholar]

- Yoshimura, A., Ideta, O. and Iwata, N. (1997) Linkage map of phenotype and RFLP markers in rice. Plant Mol. Biol. 35: 49–60 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamamoto, T., Horisue, N. and Ikeda, R. (1996) Rice breeding manual. Yokendo Co. Ltd., Tokyo, Japan, pp. 3–156 [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.