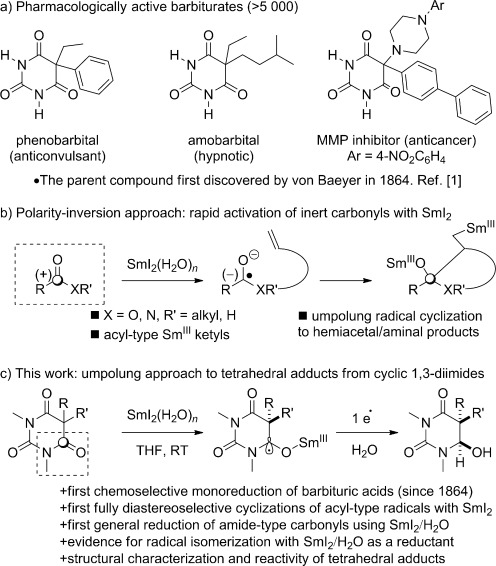

Since the 1864 landmark discovery by Adolf von Baeyer,1 barbituric acids have played a prominent role in medicine and organic synthesis. The barbituric acid scaffold occurs in more than 5000 pharmacologically active compounds, including commonly used anticonvulsant, hypnotic, and anticancer agents (Figure 1 a).2 Moreover, as an easily accessible feedstock material, it is an extremely useful building block for organic synthesis.3 However, despite the fact that barbiturates have been extensively studied for over a century, the general monoreduction of barbituric acids remains unknown,4 even though it would have considerable potential for the production and discovery of pharmaceuticals, materials, and polymers. Interestingly, the barbiturate monoreduction products would formally constitute a new class of tetrahedral intermediates of amide bond addition reactions, only few of which have been successfully isolated to date because of their transient nature.5

Figure 1.

a) Examples of pharmacologically active barbiturates. b) Polarity inversion strategy using SET approach. c) This study.

Single-electron-transfer reactions open up unexplored reaction space charted with chemoselectivity and reactivity levels difficult to access by ionic reaction mechanisms.6 The generation of ketyl-type radicals with SmI2 is particularly valuable in this regard because of the excellent chemoselectivity imparted by the reagent and the potential to effect polarity reversal of the carbonyl group through a single-electron-reduction event (Figure 1 b).7, 8 However, the selective reduction of amide carbonyls with SmI2 is challenging and no general method to achieve this highly desirable transformation is currently available.9

Herein, we demonstrate that the SmI2/H2O reagent10 can perform the selective monoreduction of barbituric acids to the corresponding hemiaminals (Figure 1 c). To our knowledge these are the first general examples of monoreduction of such systems4 as well as the reduction of amide-type carbonyls with SmI2.7, 8 The hemiaminal products are analogous to tetrahedral intermediates derived from amide addition reactions.5 Moreover, the radical intermediates formed by the one-electron reduction have been utilized in intramolecular additions to alkenes. For the first time in any SmI2-mediated cross-couplings of acyl-type radicals,11 these additions proceed with full control of diastereoselectivity.12 Furthermore, experimental evidence is provided for the isomerization of vinyl radical intermediates under SmI2/H2O reaction conditions. This discovery opens the door for the use of SmI2/H2O in cascade reductive processes employing C-centered radicals.13 Overall, these studies provide a basis for multiple methodologies to form versatile hemiaminal products (cf. hemiacetals) by a formal amide polarity reversal event.6

We hypothesized that single-electron reduction of barbituric acids (cyclic 1,3-diimides) to their respective radical anions could provide a benchmark for the development of a general system for the reduction of a wide range of amide functional groups. We considered that 1) in the barbituric acid system the reduction of one of the imide carbonyls would be enhanced because of its lower energy π*CO orbital, 2) the reduction would be favored by anomeric stabilization of the radical anion intermediate, and 3) the nN→π*CO delocalization into the remaining carbonyl in a conformationally locked system would provide access to stable, and unusual, hemiaminal products.

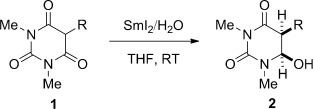

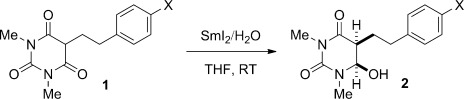

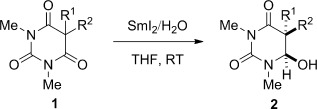

After extensive optimization of the reaction conditions, we determined that barbituric acids are reduced with SmI2/H2O to the corresponding hemiaminals in good yields and diastereoselectivities (Table 1). Typically, a twofold excess of reagent was used to ensure that the reactions were complete. A wide range of substrates exhibited excellent reactivity, including those with sensitive α protons (entries 1–8), as well as those with sterically hindered quaternary centers (entries 9–11). Importantly, the method tolerates functional groups that are typically reduced under single-electron-transfer conditions, including aromatic rings (entries 4 and 5), ethers (entry 6), trifluoromethyl groups (entry 7), and halides (entry 8). The potential of the reaction to streamline synthetic routes by sequential reductive processes has also been demonstrated (entries 12 and 13). Several products bear close analogy to the pharmacologically active barbiturates (entry 3: amobarbital, entry 10: butalbital).

Table 1.

Reduction of barbituric acids using SmI2.[a]

| Entry | 1,3-Diimide | Product | Yield [%] | d.r. [%] |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||

| 1 | 1 a, R=iBu | 2 a | 83 | 88:12 |

| 2 | 1 b, R=C10H21 | 2 b | 56 | 86:14 |

| 3 | 1 c, R=(CH2)2iPr | 2 c | 80 | 91:9 |

| 4 | 1 d, R=(CH2)2Ph | 2 d | 75 | 88:12 |

| 5 | 1 e, R=(CH2)2CHMePh | 2 e | 78 | 85:15 |

| ||||

| 6 | 1 f, X=MeO | 2 f | 80 | 88:12 |

| 7 | 1 g, X=CF3 | 2 g | 76 | 85:15 |

| 8 | 1 h, X=Br | 2 h | 67 | 87:13 |

| ||||

| 9 | 1 i, R1=Me, R2=C10H21 | 2 i | 71 | 77:23 |

| 10 | 1 j, R1=Me, R2=iBu | 2 j | 50 | 87:13 |

| 11 | 1 k, R1,R2=-(CH2)2CH=CH(CH2)2- | 2 k | 55 | – |

| 12[b] | 1 l, R1,R2= =C(OH)Bn | 2 l | 76 | 87:13 |

| 13[b] | 1 m, R1,R2= =CHiPr | 2 m | 58 | 88:12 |

[a] Reaction conditions: SmI2 (4 equiv), THF, H2O, 10–60 s. [b] Reaction conditions: SmI2 (6–8 equiv), THF, H2O, 10–60 s. See the Supporting Information for full experimental details. THF=tetrahydrofuran.

We determined that the use of H2O is critical for the observed reactivity, which is in line with the formation of a more thermodynamically powerful reductant required to activate amide-type carbonyls.14 No over-reduction is seen, even in the presence of excess reagent. Other SmI2-based systems,15 including reductants with a higher redox potential than SmI2/H2O, such as those with alcohols (MeOH, tBuOH, EG), Lewis bases (HMPA, Et3N), or salts (LiCl) did not provide the desired products.15 Competition experiments (see the Supporting Information) illustrate that SmI2/H2O is selective for cyclic 1,3-diimides over reactive six-membered lactones, thus suggesting that significant levels of selectivity are possible with this reagent system.

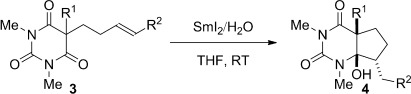

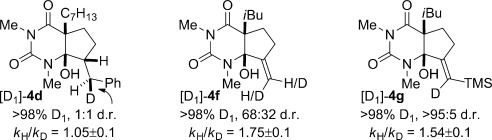

To further evaluate the potential of our method, we examined several substrates bearing an unactivated π system tethered to the barbituric acid scaffold (Table 2). A broad range of cyclic 1,3-diimides bearing alkene (entries 1–5) and alkyne (entries 6–9) substitutents underwent efficient radical cyclizations, thus resulting in the formation of bicyclic hemiaminals in good to excellent yields. For the first time in any radical cyclization mediated by SmI2/H2O, all products were formed with a high degree of stereoisomeric control around the five-membered ring.11 We hypothesize that the increased half-life of the acyl-type radical, stabilized by the nN→SOMO conjugation (cf. esters),16 permits the alkene tether to adopt the lowest energy conformation before the cyclization. This finding bodes well for the development of other SmI2-promoted radical cyclizations based on amide bond umpolung.

Table 2.

Reductive coupling of barbituric acids using SmI2.[a]

| Entry | 3 | R1 | R2 | 4 | Yield [%] | d.r. [%] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||

| 1 | 3 a | iBu | H | 4 a | 74 | >95:5 |

| 2 | 3 b | iBu | Ph | 4 b | 58 | >95:5 |

| 3 | 3 c | iBu | 4-MeOC6H4 | 4 c | 59 | >95:5 |

| 4 | 3 d | C7H13 | Ph | 4 d | 64 | >95:5 |

| 5 | 3 e | C4H7 | H | 4 e | 55 | >95:5 |

| ||||||

| 6 | 3 f | iBu | H | 4 f | 63 | >95:5 |

| 7 | 3 g | iBu | TMS | 4 g | 66 | >95:5[b] |

| 8 | 3 h | iBu | Ph | 4 h | 90 | 63:37[c] |

| 9 | 3 i | C4H5 | H | 4 i | 82 | >95:5 |

[a] Reaction conditions: SmI2 (6 equiv), THF, H2O, 1–15 min. See the Supporting Information for full experimental details. [b] E isomer; >95:5 d.r. [c] Z/E geometry. TMS=trimethylsilyl.

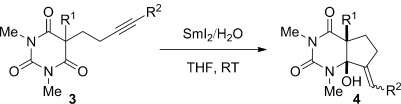

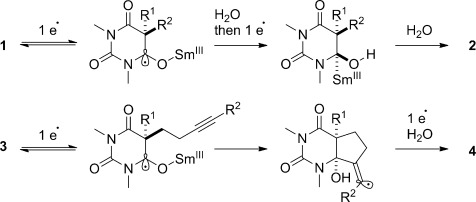

We have carried out preliminary studies to elucidate the mechanism of the reaction (see the Supporting Information for details): 1) The reduction of 1 i with SmI2/D2O (>98 % D1; kH/kD=1.5±0.1)11a suggests that anions are generated and protonated by H2O in a series of electron-transfer steps and that proton transfer is not involved in the rate-determining step of the reaction.17 2) Control experiments with a cyclic 1,3-malonamide and DMPU demonstrate that activation of the amide carbonyl facilitates the reaction. 3) Intermolecular competition experiments show that the rate of the reduction can be modified by steric and electronic substitution at the α-carbon atom. 4) Deuterium incorporation and KIE studies on the reductive cyclizations suggest that proton transfer is not involved in the rate-determining step (Figure 2). 5) The reaction of 3 d to give [D1]-4 d (1:1 d.r.) demonstrates that the benzylsamarium(III) intermediate is not coordinated to the hydroxy group (Figure 2).11a 6) The reactions of 3 f and 3 g indicate inversion of the vinyl radical18 under the reduction conditions (Figure 2). 7) A gradual change in diastereoselectivity is observed in the cyclizations of 3 h at varied concentrations of H2O,10 additionally suggesting that the carbon-centered radicals do not undergo instantaneous reduction/protonation.14 8) Finally, intermolecular competition experiments indicate that the rate of the cyclization is governed by electronic and steric properties of the π acceptor,19 suggesting significant levels of chemoselectivity in these cyclizations.8i

Figure 2.

Reductive coupling of barbituric acids 3 d, 3 f, and 3 g using SmI2/D2O (only products are shown).

A proposed mechanism is shown in Scheme 1. We hypothesize that the kinetic diastereoselectivity in the reduction results from the formation of an organosamarium(III) on the less hindered face of the molecule. This is analogous to the classic reduction of cyclic ketones to equatorial alcohols by related SmI2/H2O systems.10 In the reductive cyclization, the radical anion undergoes an anti addition20 to give the vinyl radical intermediate, which isomerizes, depending on the steric and electronic preferences of the π acceptor and the reaction conditions. Control experiments (see the Supporting Information) point to the critical role of H2O in stabilizing the radical anion14 and promoting cyclization (no reaction is observed in the absence or at low concentration of H2O as well as with more powerful SmI2-based reductants, SmI2/LiCl and SmI2/HMPA).

Scheme 1.

Mechanism of the reduction and cyclization of barbituric acids using SmI2/H2O.

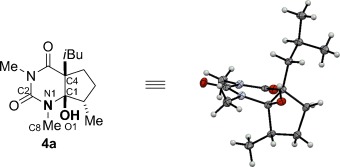

The α-amino alcohol moiety derived from barbituric acid reduction is stabilized by a nonplanar arrangement of atoms (Figure 3). The X-ray crystal structure of 4 a reveals that the C1–O1 bond (1.407 Å) is shorter than the average Csp3–O bond (1.432 Å),5a whereas the length of N1–C1 bond is 1.466 Å, which corresponds to a typical Csp3–N bond (1.469 Å).5a The C1–C4 bond length of 1.552 Å is slightly longer than the average Csp3–Csp3 bond (1.530 Å).5a The torsion angle between N lp (lp=lone pair) and C1–O1 bond of 57.3° is consistent with the absence of N lp→σ*C−O interactions. However, there is a good overlap between the O1 lp1 and the N1–C1 bond (ca. 172°) and between O1 lp2 and the C1–C4 bonds (ca. 191°). The shortened C1–O1 bond and the elongated C1–C4 bond are consistent with an anomeric effect resulting from O lp1→σ*C1–N1 and O lp2→σ*C1–C4 interactions, while the geometry of the N1 atom indicates the beginning of the decomposition of the tetrahedral intermediate by the elimination of N(CO) group. It should be noted that the α-amino alcohol function in this system is stabilized by the reduced N lp→σ*C1–O1 conjugation because of the interaction of N lp with the adjacent carbonyl group.

Figure 3.

X-ray structure of 4 a. Selected bond lengths [Å] and angles [°]: N1–C1 1.466, C1–O1 1.407, C1–C4 1.552, C1-H1 0.84, N1–C2 1.354, C2–O2 1.218, N2–C2 1.421; C2-N1-C1-O1 155.1, C8-N1-C1-O1 −40.6, N1-C1-O1-H1 −52.1, C4-C1-O1-H1 70.8, C1-N1-C2-N2 −6.9, C2-N2-C3-C4 −14.6, N1-C2-N2-C3 −3.6.23

Interestingly, the X-ray structure of the monocyclic analogue 2 f shows kinetic rather than thermodynamic stability (see the Supporting Information). The torsion angles between N lp and C1–O1 of about 175° and O lp and C1–N1 of about 37° indicate a significant N lp→σ*C1–O1 interaction in this system, and the absence of O lp→σ*C1–N1 conjugation. The O1-C1-C4-H4 torsion angle of approximately 180° reveals a perfect antiperiplanar arrangement between the α-hydrogen atom and the hydroxy group. These parameters are consistent with the beginning of the decomposition of the α-amino alcohol moiety by the elimination of a hydroxy group to give acyliminium. Overall, these features seem to be characteristic of the α-amino alcohol function stabilized by scaffolding effects in a barbituric acid system and indicate that isolation of a range of analogues can be readily achieved.

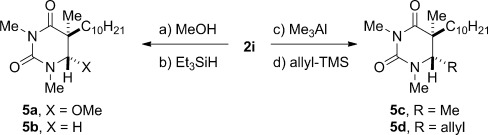

Finally, we have preliminary results pertaining to the reactivity of these hemiaminals (Scheme 2). We determined that the alcohol could be directly displaced with a variety of heteroatom and carbon nucleophiles under mild reaction conditions. We also showed that the N,N-phenobarbital-derived hemiaminal undergoes an unprecedented 1,2-aryl shift (see the Supporting Information). These results bode well for accessing a wide range of biologically active uracil derivatives.21

Scheme 2.

Reactivity of the tetrahedral adducts 2. Reaction conditions: a) MeOH, HCl, RT, 3 h, 99 %. b) Et3SiH, BF3⋅Et2O, RT, 3 h, 96 %. c) Me3Al, RT, 3 h, 78 %. d) allyl-TMS, BF3⋅Et2O, RT, 2 h, 86 %.

In summary, we have developed the first general method for the monoreduction of barbituric acids since their seminal discovery in 1864 by von Baeyer. This reaction constitutes the first general method for the reduction of amide-type carbonyls using SmI2.22 The radicals formed by one-electron reduction of the amide bond have been applied in intramolecular additions to alkenes. The cyclic hemiaminal products are analogous to tetrahedral intermediates derived from amide addition reactions and are formed in a formal polarity reversal event. We fully expect that the present work will provide the basis for the synthesis of novel barbituric acid derivatives and will result in the development of an array of modern synthetic methodologies to access reductive amide umpolung by electron transfer events.

Supplementary material

As a service to our authors and readers, this journal provides supporting information supplied by the authors. Such materials are peer reviewed and may be re-organized for online delivery, but are not copy-edited or typeset. Technical support issues arising from supporting information (other than missing files) should be addressed to the authors.

References

- 1a.von Baeyer A. Justus Liebigs Ann. Chem. 1864;130:129. for the first mention of barbituric acid by von Baeyer, see: [Google Scholar]

- 1b.von Baeyer A. Justus Liebigs Ann. Chem. 1863;127:199. selected historical perspectives: [Google Scholar]

- 1c.Carter MK. J. Chem. Educ. 1951;28:524. [Google Scholar]

- 1d.Kauffmann GB. J. Chem. Educ. 1980;57:222. [Google Scholar]

- 1e.de Meijere A. Angew. Chem. 2005;117:8046. [Google Scholar]

- Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2005;44:7836. [Google Scholar]

- 1f.Jones AW. Perspectives in Drug Discovery. Linköping; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 2a.Bojarski JT, Mokrosz JL, Barton HJ, Paluchowska MH. Adv. Heterocycl. Chem. 1985;38:229. Reviews: [Google Scholar]

- 2b.Abraham DJ, Rotella DP. Burger’s Medicinal Chemistry, Drug Discovery and Development. Hoboken: Wiley; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 2c.López-Muñoz F, Ucha-Udabe R, Alamo C. Neuropsychiatr. Dis. Treat. 2005;1:329. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2d.Seeliger F, Berger STA, Remennikov GY, Polborn K, Mayr H. J. Org. Chem. 2007;72:9170. doi: 10.1021/jo071273g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3a.Takenaka K, Itoh N, Sasai H. Org. Lett. 2009;11:1483. doi: 10.1021/ol900016g. Selected recent applications: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3b.Holzwarth M, Dieskau A, Tabassam M, Plietker B. Angew. Chem. 2009;121:7387. doi: 10.1002/anie.200901930. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2009;48:7251. [Google Scholar]

- 3c.Fujimori S, Carreira EM. Angew. Chem. 2007;119:5052. doi: 10.1002/anie.200701098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2007;46:4964. [Google Scholar]

- 3d.Schmidt MU, Brüning J, Glinnemann J, Hützler MW, Mörschel P, Ivashevskaya SN, van de Streek J, Braga D, Maini L, Chierotti MR, Gobetto R. Angew. Chem. 2011;123:8070. doi: 10.1002/anie.201101040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2011;50:7924. [Google Scholar]

- 3e.Mori K, Sueoka S, Akiyama T. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2011;133:2424. doi: 10.1021/ja110520p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3f.Reddy Chidipudi S, Khan I, Lam HW. Angew. Chem. 2012;124:12281. doi: 10.1002/anie.201207170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2012;51:12115. [Google Scholar]

- 3g.Daniewski AR, Liu W, Okabe M. Org. Process Res. Dev. 2004;8:411. [Google Scholar]

- 3h.Ruble JC, Hurd AR, Johnson TA, Sherry DA, Barbachyn MR, Toogood PL, Bundy GL, Graber DR, Kamilar GM. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2009;131:3991. doi: 10.1021/ja808014h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3i.Huang X, Li C, Jiang S, Wang X, Zhang B, Liu M. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2004;126:1322. doi: 10.1021/ja036878i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4a.Dudley KH, Davis IJ, Kim DK, Ross FT. J. Org. Chem. 1970;35:147. doi: 10.1021/jo00826a033. Ring scission and over-reduction have been observed in reactions with other reductants: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4b. See, Ref. [2a]

- 5a.Adler M, Adler S, Boche G. J. Phys. Org. Chem. 2005;18:193. For reviews, see: [Google Scholar]

- 5b.Deslongchamps P. Stereoelectronic Effects in Organic Chemistry. Elmsford, NY: Pergamon Press; 1983. examples of isolated tetrahedral intermediates: [Google Scholar]

- 5c.Kirby AJ, Komarov IV, Feeder N. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1998;120:7101. [Google Scholar]

- 5d.Evans DA, Borg G, Scheidt KA. Angew. Chem. 2002;114:3320. doi: 10.1002/1521-3773(20020902)41:17<3188::AID-ANIE3188>3.0.CO;2-H. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2002;41:3188. [Google Scholar]

- 5e.Cox C, Wack H, Lectka T. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1999;121:7963. [Google Scholar]

- 5f.Szostak M, Aubé J. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2010;132:2530. doi: 10.1021/ja910654t. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5g.Adler M, Marsch M, Nudelman NS, Boche G. Angew. Chem. 1999;111:1345. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1521-3773(19990503)38:9<1261::AID-ANIE1261>3.0.CO;2-E. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 1999;38:1261. [Google Scholar]

- 6a.Trost BM, Fleming I. Comprehensive Organic Synthesis. New York: Pergamon; 1991. Reviews on metal-mediated radical reactions: [Google Scholar]

- 6b.Gansäuer A, Blum H. Chem. Rev. 2000;100:2771. doi: 10.1021/cr9902648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6c.Szostak M, Procter DJ. Angew. Chem. 2012;124:9372. doi: 10.1002/anie.201201065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2012;51:9238. [Google Scholar]

- 6d.Gansäuer A. Topics in Current Chemistry, Vol. 263–264. Heidelberg: Springer; 2006. “Radicals in Synthesis I and II”: an excellent review on reductive umpolung: [Google Scholar]

- 6e.Streuff J. Synthesis. 2013;45:281. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Procter DJ, II RAFlowers, Skrydstrup T. Organic Synthesis using Samarium Diiodide: A Practical Guide. Cambridge: RSC Publishing; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 8a.Molander GA, Harris CR. Chem. Rev. 1996;96:307. doi: 10.1021/cr950019y. For reviews, see: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8b.Krief A, Laval AM. Chem. Rev. 1999;99:745. doi: 10.1021/cr980326e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8c.Kagan HB. Tetrahedron. 2003;59:10351. [Google Scholar]

- 8d.Edmonds DJ, Johnston D, Procter DJ. Chem. Rev. 2004;104:3371. doi: 10.1021/cr030017a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8e.Nicolaou KC, Ellery SP, Chen JS. Angew. Chem. 2009;121:7276. doi: 10.1002/anie.200902151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2009;48:7140. [Google Scholar]

- 8f.Szostak M, Procter DJ. Angew. Chem. 2011;123:7881. doi: 10.1002/anie.201103128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2011;50:7737. [Google Scholar]

- 8g.Beemelmanns C, Reissig HU. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2011;40:2199. doi: 10.1039/c0cs00116c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8h.Sautier B, Procter DJ. Chimia. 2012;66:399. doi: 10.2533/chimia.2012.399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8i.Szostak M, Spain M, Procter DJ. Chem. Soc. Rev. DOI: 10.1039/c3cs60223k; extremely relevant review about chemoselective electron transfer using SmI2. [Google Scholar]

- 9a.Jensen CM, Lindsay KB, Taaning RH, Karaffa J, Hansen AM, Skrydstrup T. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2005;127:6544. doi: 10.1021/ja050420u. Skrydstrup and co-workers reported an elegant coupling of N-acyl oxazolidinones by a radical addition mechanism: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9b.Hansen AM, Lindsay KB, Antharjanam PKS, Karaffa J, Daasbjerg K, Flowers RA, II, Skrydstrup T. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2006;128:9616. doi: 10.1021/ja060553v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9c.Taaning RH, Lindsay KB, Schiøtt B, Daasbjerg K, Skrydstrup T. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2009;131:10253. doi: 10.1021/ja903401y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9d.Ebran JP, Jensen CM, Johannesen SA, Karaffa J, Lindsay KB, Taaning RH, Skrydstrup T. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2006;4:3553. doi: 10.1039/b608028f. Namy reported coupling of imides via a fragmentation mechanism: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9e.Farcas S, Namy JL. Tetrahedron Lett. 2000;41:7299. Ha et al. and Farcas and Namy reported the addition of organosamariums to imides: [Google Scholar]

- 9f.Ha DC, Yun CS, Lee Y. J. Org. Chem. 2000;65:621. doi: 10.1021/jo9913762. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9g.Farcas S, Namy JL. Tetrahedron Lett. 2001;42:879. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Szostak M, Spain M, Parmar D, Procter DJ. Chem. Commun. 2012;48:330. doi: 10.1039/c1cc14252f. For a recent review, see: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11a.Parmar D, Duffy LA, Sadasivam DV, Matsubara H, Bradley PA, Flowers RA, II, Procter DJ. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2009;131:15467. doi: 10.1021/ja906396u. For selected studies, see: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11b.Collins KD, Oliveira JM, Guazzelli G, Sautier B, De Grazia S, Matsubara H, Helliwell M, Procter DJ. Chem. Eur. J. 2010;16:10240. doi: 10.1002/chem.201000632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11c.Parmar D, Price K, Spain M, Matsubara H, Bradley PA, Procter DJ. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2011;133:2418. doi: 10.1021/ja1114908. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11d.Parmar D, Matsubara H, Price K, Spain M, Procter DJ. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2012;134:12751. doi: 10.1021/ja3047975. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11e.Sautier B, Lyons SE, Webb MR, Procter DJ. Org. Lett. 2012;14:146. doi: 10.1021/ol2029367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Molander GA, Harris CR. Tetrahedron. 1998;54:3321. For a classic review on SmII-mediated cascade cyclizations, see. [Google Scholar]

- 13a.Duffy LA, Matsubara H, Procter DJ. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2008;130:1136. doi: 10.1021/ja078137d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13b.Guazzelli G, De Grazia S, Collins KD, Matsubara H, Spain M, Procter DJ. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2009;131:7214. doi: 10.1021/ja901715d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13c.Szostak M, Spain M, Procter DJ. Nat. Protoc. 2012;7:970. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2012.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13d.Szostak M, Spain M, Procter DJ. Chem. Commun. 2011;47:10254. doi: 10.1039/c1cc14014k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13e.Szostak M, Spain M, Procter DJ. Org. Lett. 2012;14:840. doi: 10.1021/ol203361k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13f.Szostak M, Collins KD, Fazakerley NJ, Spain M, Procter DJ. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2012;10:5820. doi: 10.1039/c2ob00017b. for a related study on TmI2/H2O, see: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13g.Szostak M, Spain M, Procter DJ. Angew. Chem. 2013;125:7378. doi: 10.1002/anie.201303178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2013;52:7237. [Google Scholar]

- 14a.Chopade PR, Prasad E, Flowers RA., II J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2004;126:44. doi: 10.1021/ja038363x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14b.Prasad E, Flowers RA., II J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2005;127:18093. doi: 10.1021/ja056352t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14c.Amiel-Levy M, Hoz S. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2009;131:8280. doi: 10.1021/ja9013997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14d.Hasegawa E, Curran DP. J. Org. Chem. 1993;58:5008. [Google Scholar]

- 15a.Dahlén A, Hilmersson G. Eur. J. Inorg. Chem. 2004:3393. [Google Scholar]

- 15b.Flowers RA., II Synlett. 2008:1427. [Google Scholar]

- 16a.Malatesta V, Ingold KU. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1981;103:609. [Google Scholar]

- 16b.Giese B. Angew. Chem. 1989;101:993. [Google Scholar]

- Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 1989;28:969. [Google Scholar]

- 16c.Cohen T, Bhupathy M. Acc. Chem. Res. 1989;22:152. [Google Scholar]

- 17a.Bender ML, Pollock EJ, Neveu MC. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1962;84:595. A value of 1.5 is likely to result from a secondary KIE arising from differential coordination of D2O/H2O to SmII. For leading references on KIE, see: [Google Scholar]

- 17b.Bigeleisen J, Wolfsberg M. In: Advances in Chemical Physics. Prigogine I, Debye P, editors. Vol. 1. Hoboken: Wiley; 1958. “Theoretical and Experimental Aspects of Isotope Effects in Chemical Kinetics”: [Google Scholar]

- 17c.Singleton DA, Thomas AA. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1995;117:9357. [Google Scholar]

- 17d.Singleton DA, Szymanski MJ. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1999;121:9455. [Google Scholar]

- 17e.Belasco JG, Albery WJ, Knowles JR. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1983;105:2475. [Google Scholar]

- 17f.O’Leary MH. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 1989;58:377. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bi.58.070189.002113. The absence of a primary KIE indicates that proton transfer is not involved in the rate-determining step of the reaction: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17g.Wiberg KB. Chem. Rev. 1955;55:713. [Google Scholar]

- 17h.Wolfsberg M. Acc. Chem. Res. 1972;5:225. [Google Scholar]

- 17i.Melander L, Saunders WH. Reaction Rates of Isotopic Molecules. Wiley; 1980. [Google Scholar]

- 17j.Simmons EM, Hartwig JF. Angew. Chem. 2012;124:3120. doi: 10.1002/anie.201107334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2012;51:3066. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fessenden RW, Schuler RH. J. Chem. Phys. 1963;39:2147. [Google Scholar]

- 19a.Curran DP, Porter NA, Giese B. Stereochemistry of Radical Reactions. Weinheim: Wiley-VCH; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 19b.Chatgilialoglu C, Studer A. Encyclopedia of Radicals in Chemistry, Biology and Materials. Chichester: Wiley-Blackwell; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Giese B. Angew. Chem. 1983;95:771. [Google Scholar]

- Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 1983;22:753. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bardagi JI, Rossi RA. Org. Prep. Proced. Int. 2009;41:479. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Szostak M, Spain M, Procter DJ. J. Org. Chem. 2012;77:3049. doi: 10.1021/jo300135v. For a detailed study on the preparation of SmI2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. CCDC 948382 (4 a) contains the supplementary crystallographic data for this paper. These data can be obtained free of charge from The Cambridge Crystallographic Data Centre via http://www.ccdc.cam.ac.uk/data_request/cif.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.