Abstract

We review the current application of deep brain stimulation (DBS) in Parkinson disease (PD) and consider the evidence that earlier use of DBS confers long-term symptomatic benefit for patients compared to best medical therapy.

Electronic searches were performed of PubMed, Web of Knowledge, Embase, Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, and Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials to identify all article types relating to the timing of DBS in PD.

Current evidence suggests that DBS is typically performed in late stage PD, a mean of 14 to 15 years after diagnosis. Current guidelines recommend that PD patients who are resistant to medical therapies, have significant medication side effects and lengthening off periods, but are otherwise cognitively intact and medically fit for surgery be considered for DBS.

If these criteria are rigidly interpreted, it may be that, by the time medical treatment options have been exhausted, the disease has progressed to the point that the patient may no longer be fit for neurosurgical intervention. From the evidence available, we conclude that surgical management of PD alone or in combination with medical therapy results in greater improvement of motor symptoms and quality of life than medical treatment alone. There is evidence to support the use of DBS in less advanced PD and that it may be appropriate for earlier stages of the disease than for which it is currently used. The improving short and long-term safety profile of DBS makes early application a realistic possibility. Ann Neurol 2013;73:565–575

Parkinson disease (PD) is the second most common neurodegenerative disease after Alzheimer disease. The incidence rate of PD is 12 to 20 per 100,000 annually in Northern Europe.1 It is estimated that there are approximately 1 million PD sufferers in the USA and 120,000 in the United Kingdom, 1 in 20 of whom are under the age of 40 years.2 An analysis of PD epidemiology suggests that the number of individuals aged >50 years with PD in the world's most populated countries will approximately double to between 8.7 and 9.3 million in 2030.3

In 2007, the global economic cost of PD was estimated to be up to £3 billion (approximately US $4.63 billion) annually.4 Recent reviews and cost analyses showed the greatest expenditure was on nursing homes and social care.5–7 Costs increase in later stage PD.8 This reinforces the notion that despite optimal medical therapy, there remains significant morbidity and disability yet to be addressed in PD.

The clinical features of PD comprise the well-recognized motor syndrome and a large number of nonmotor manifestations.9 Medication side effects, psychological morbidity, poor quality of life, and the burden on carers are important components that make PD a complex, chronic, multifaceted disease.

The mainstay of treatment for PD is currently medical, surgical, and supportive treatment. Among surgical treatments, there is currently level 1 evidence that deep brain stimulation (DBS) of the subthalamic nucleus (STN) and the globus pallidus internus (GPi) is effective in improving L-dopa–responsive signs in PD patients.10–13 Traditionally, DBS has been typically left until late stage PD, a mean of 14 to 15 years after diagnosis,14–16 although this may not necessarily reflect current practice. Continued interest in surgical therapies for PD is encouraged by the increasing awareness of the adverse effects and limitations of medical therapy for PD as well as advances in medical imaging and bioengineering technology. STN DBS received US Food and Drug Administration approval for use in PD in 2002 and GPi DBS received it in 2003. Work then centered on finding the ideal nucleus to target.13–19

The initial criteria of inclusion for DBS have been relatively strict and include the presence of significant disability but the absence of cognitive dysfunction.20,21 The UK National Institute for Clinical Excellence (NICE) guidelines have recommended that PD patients who are resistant to medical therapies, have severe medication side effects and lengthening off periods, but are medically and psychologically fit for surgery, be considered for DBS.22 If these criteria are rigidly interpreted, it might be that, by the time medical treatment options have been exhausted, the disease has progressed to the point that the patient may no longer be fit enough for neurosurgical intervention. The 2006 consensus on treatments for PD acknowledged this potentially critical issue in patient selection, proposing individualized criteria for selection (disability, quality of life, expectations of functionality, interpersonal relationships), good response to L-dopa (the only positive predictor of DBS benefit), and recommended further research into the use of surgery earlier in the course of PD.23

The purpose of this review is to consider whether earlier use of DBS confers long-term symptomatic benefit for patients compared to best medical therapy, and to review the evidence suggesting DBS has a disease-modifying role.

Current Medical Management of PD

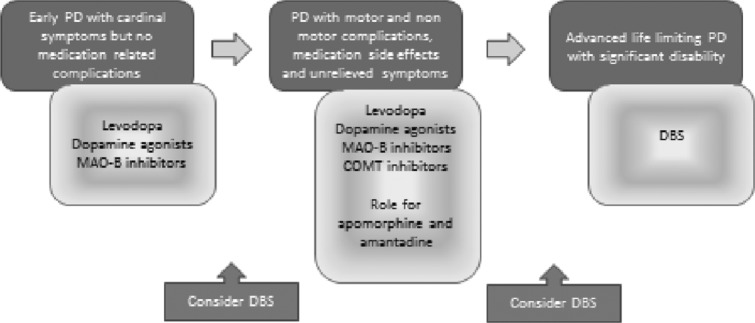

Following a diagnosis of PD, NICE considers the management in 3 main tiers: management of early PD (functional effect of disease apparent), management of late PD (motor complications), and surgical management.24 The Movement Disorder Society also used critical appraisal of the literature to offer guidelines on management of uncomplicated and complicated PD.25 Combination therapy is recognized to be a common feature at all stages. The unmet needs of PD management include control of nonmotor features, motor complications, and the development of disease-modifying therapies.26–29 Currently, medical therapy remains the first-line treatment for PD, and DBS should only be considered for selected patients in whom medical therapy is failing and its effectiveness is limited by side effects.

Current Use of DBS in PD

The current indications and patient selection criteria for DBS have recently been reviewed.23,30,31 For DBS to be considered, most importantly the patient must have dopamine-responsive PD. The patient should not have significant cognitive dysfunction, and should be emotionally stable with no active severe psychiatric symptoms. Both sporadic and genetic PD patients are eligible for DBS.30

Because cognitive, affective, and psychotic symptoms are part of the (late) natural history of PD and medical comorbidities increase with age and debility, it is possible that by waiting too long to perform DBS we are turning potential DBS candidates into exclusion cases.32,33

The benefits of DBS include motor and nonmotor function attenuation of drug-induced dyskinesias and improvement in quality of life.10,16,34,35

In terms of motor benefits, DBS reduces off symptoms by 60%, rapidly reduces medication-induced dyskinesias in STN DBS by 60 to 80% as medication requirements are less, and improves Unified Parkinson Disease Rating Scale (UPDRS) scores and self-assessed quality of life.10,15,34 Although many claims have been made regarding the relative benefits of STN versus GPi stimulation, only well-designed studies with homogeneous reporting methods of outcomes will enable robust discrimination of benefit between different DBS sites and techniques.36 STN DBS was shown in a level 3 study of 30 patients to be associated with maintenance of the long-term L-dopa response but worsening of the short-term L-dopa response in advanced PD, a situation mimicking early stage PD.37 Long-term data are now emerging, and indicate that DBS motor benefits are still clinically apparent at 10 years.19,38,39 The 10-year follow-up of 18 patients showed that STN DBS resulted in significant improvement in tremor, bradykinesia, and total motor score but not axial motor function and not activities of daily living (ADL) scores.39 There are studies comparing STN and GPi DBS in terms of long-term benefit. A 5-year prospective study of 35 STN patients and 16 GPi patients showed STN DBS to be associated with greater motor benefit than GPi DBS in some domains (off-medication UPDRS, dyskinesias, and ADL).19 A randomized trial of 159 patients with PD showed significant improvements in 36-month motor UPDRS on-stimulation/on-medication and off-stimulation/off-medication, both of which favored GPi, but there was no difference in overall quality of life measures at this time point, although dementia rating scales declined faster in the STN group.17 This study also showed stability of benefits at 3 years.17 The COMPARE trial examined the effects of GPi versus STN DBS on cognition and mood in 45 patients with a mean PD duration of 13 years.11 No overall difference was observed between the groups, but verbal fluency was worse at 7 months after STN than GPi DBS.11 Both STN and GPi DBS offer advantages,40 and the differences between these may only become apparent in studies with >5 years follow-up postimplantation.19,31,34,41 Studies addressing the effect of DBS on symptoms also report improvement of nonmotor features of PD such as pain, akathisia, cognitive function, emotion, ADL, and autonomic function.42–47

The choice between STN and GPi DBS and whether unilateral, bilateral, or staged bilateral is based upon the patient's individual symptoms and the surgeon's experience. There is no level 1 evidence that demonstrates superiority of either site. There is level 2 and 3 evidence showing that choice and laterality of site can affect individual motor and nonmotor features (for example postural response, verbal fluency, and quality of life), but no evidence to generate firm recommendations on situations where STN or GPi would be more effective. A 6-year multicenter follow-up study showed no difference in efficacy between STN and GPi, but did show a lower incidence of DBS complications in the GPi group.19,48–50

The adverse events associated with DBS are a key consideration in whether to perform this procedure more liberally. Side effects can be operation, hardware, or stimulation related (Table1).51 They can be immediate, early, or delayed and be motor or nonmotor. The incidence of complications is lower in large centers that specialize in DBS.51

TABLE 1.

Complications of DBS

| Operation related | Intracerebral hematoma, 0–10% Chronic subdural hematoma Incorrect placement of electrodes or leads Air embolism Death, 0–4.4% Complications of anesthesia Infection (most common complication), up to 15%31 |

| Hardware related | Interaction with cardiac pacemakers112 Electrode migration, 0–19%10 Lead fracture, 0–15% Lead erosion, 1–2.5% Foreign body reaction Skin erosion Interaction with diathermy causing tissue damage Cognitive decline |

| Stimulation related | Psychiatric disturbance including mania, depression, impulse control disorders, psychosis, and suicidal ideation Weight gain Sensory disturbance Speech, visual, and auditory disorders including apraxia of eyelid opening Dyskinesias and dystonia Reduction in verbal fluency |

Percentages are provided where available. See text for details.

DBS = deep brain stimulation; MRI = magnetic resonance imaging.

From a 2011 consensus on DBS in PD, the most common surgical complications reported in the available literature were infection (0–15%), bleeding (0–10%), stroke (0–2%), lead erosion (1–2.5%), lead breakage (0–15%), lead migration (0–19%), and death (0–4.4%).30 Hardware complications may necessitate a second procedure. Neuropsychiatric adverse effects reported include severe depression, increased suicide risk,52 apathy, anxiety,53,54 decreased frontal cognitive function,55 obsessive–compulsive disorder, impulse control disorders, and aggression.56–60 Recent data suggest bilateral STN stimulation might be associated with some worsening of motor and cognitive performance on complex dual task testing, whereas unilateral STN stimulation would not cause this problem.61 Recent work, investigating the mechanisms of psychiatric symptoms post-DBS using [11C]-raclopride positron emission tomography (PET) scans of 12 patient with post–STN-DBS apathy, suggests that this symptom is associated with dopamine denervation in the mesolimbic circuits,62 and apathy may be related at least in part to anti-PD drug reduction and withdrawal after surgery, rather than the direct effect of STN DBS. Other DBS-related possible complications in PD include weight gain63; sleep disorders64; eyelid opening apraxia65; speech, gait, and balance worsening; and hypersexuality.66 As indicated above, impaired verbal fluency is a known side effect of DBS11 and may be a surgical effect.67 Clinical effectiveness of DBS may not translate into a quality of life benefit in older patients.68 DBS in a younger population seems to have a higher impact on improving their quality of life and helping to maintain active, independent lifestyles. It is possible that the incidence of serious adverse events during DBS will be less in patients with milder PD, who are likely to be younger with fewer comorbidities.

Evidence Comparing DBS and Medical Treatments

There have been a number of trials comparing optimal medical management and DBS (with or without concurrent medical management). Three randomized controlled trials show that STN DBS results in improved patient-reported quality of life.10,12,69 Significant motor and consequent functional improvement was demonstrated by surgical patients experiencing greater improvement in UPDRS scores at 6 months post-DBS than medically managed patients in a randomized pairs trial of 156 patients who had been on L-dopa for a mean of 13 years.10 The PD SURG randomized open label trial compared best medical therapy and surgery (either stimulation or lesioning of the STN or the GPi). This randomized controlled trial of bilateral DBS versus medical therapy evaluated 255 patients who had taken PD medications for a mean of 10 to 12 years. After 6 months of follow-up, those who had DBS showed significant improvement in motor function, motor side effects, and quality of life.12 However, quality of life improvement should be balanced against the incidence of severe surgery-related side effects such as intracranial hemorrhage and infection, and stimulation-related side effects, such as worsening of axial signs, particularly speech.12

The economic impact of DBS for PD has been explored in modeling studies.70 Specific DBS-related expenses such as equipment, surgical theater time, and hardware as well as long-term costs such as social care are relevant.71 Broad assessment tools are necessary for cost-effectiveness in view of the “acute on chronic” nature of DBS (ie, combination of initial surgical costs and long-term social care costs).71 Comparative cost analyses of DBS and optimal medical therapy concluded that DBS may be more efficient clinically on the basis of UPDRS scores, and economically effective primarily through a reduction in drug requirements and delay in nursing care costs.72–74

From the evidence available, surgical management of PD alone or in combination with medical therapy offers the potential for greater improvement of motor symptoms and quality of life than medical treatment alone. DBS is now an established therapy for PD and has an endorsed safety profile. Therefore, an important issue is whether DBS should be considered earlier in the course of the disease to maintain and preserve function rather than rescue the patient. This is especially true in aspects of life such as employment, family roles, and social interaction.

Evidence for Earlier Use of DBS for Symptomatic Benefit in PD

Those in favor of commencing DBS before drug-induced motor complications become established argue that patients would benefit sooner from improved motor symptoms and quality of life. Opponents state that DBS has potentially serious risks associated with it and therefore should not be used except as a last resort. There are currently no strict criteria defining “early” DBS. Most groups consider it in terms of disease severity, treatment-related complications, and disability rather than as a time-dependent process. As research into DBS at different stages of PD evolves, it is possible that specific motor, nonmotor, and functional criteria for early DBS will emerge.

There is a modest volume of level 2 evidence that addresses the symptomatic benefits of early DBS (Table2). A prospective randomized trial of early DBS (PD duration mean = 2.1 years) in 30 patients has been commenced and at 3 months reports that surgical complication rate and lead placement were not significantly different in the early DBS group and were in keeping with reported data.75 In a randomized trial addressing the symptomatic effects of bilateral STN DBS in 10 patients with early PD (defined according to duration of disease and UPDRS III score) compared to 10 matched medically treated controls,76 a significant benefit from DBS on quality of life, motor signs, reduced motor complications, and L-dopa requirement was observed.68 The side effects of DBS were reported as temporary and mild. This study, although small, highlights the clinical benefits and safety profile of early use of DBS in relief of motor symptoms. In terms of disadvantages of DBS, a separate study on the same group of patients reports that patients with DBS experienced long-term psychosocial, family, and professional difficulties, elements of which were already present preoperatively.77 It is known that poor preoperative affective state may predict continued depression post-DBS.78

Table 2.

Studies Addressing Use of DBS Earlier in Parkinson Disease

| First Author and Year | Summary | Study Type | Patients, No. | Timing of DBS and Outcome Measures | Follow-up, mo | Motor and Nonmotor Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Shichi 2005113 | Unilateral DBS in early stage unilateral PD | Prospective | 6 | UPDRS and Schwab England ADL score before and after DBS. DBS defined as early but actual timing unknown. | 6 | UPDRS without medication improved by 64%. Schwab England ADL score 23%. |

| Schupbach 200776 | Bilateral STN DBS vs optimal medical therapy | RCT | 20 | Early PD patients (mean 7 years duration) with mild to moderate motor signs included. Outcome measures were motor scores, quality of life, cognition, and psychiatric morbidity. | 18 | Significant improvement in motor signs, medication use, and quality of life in the operated group. |

| Yamada 200979 | UPDRS and independence of ADL assessment in bilateral STN DBS | Retrospective evaluation of prospective database | 38 | UPDRS, Schwab England ADL. | 3 | UPDRS scores for neuropsychiatric, axial, and ADL impairments negatively correlated with postoperative Schwab England ADL with off-medication status (p < 0.01). |

| Khan 201275 | Prospective randomized trial of STN DBS in early PD | RCT, randomized to DBS at mean 2.1 years PD duration | 30 | No results available yet except surgical morbidity data in keeping with reported values. | ||

| Deuschl 201380 | Trial of STN DBS vs best medical treatment in PD patients with ≤3 years duration of motor complications (EARLYSTIM trial) | Prospective randomized multicenter trial | Primary outcome measure was quality of life (Parkinson's Disease Questionnaire). Secondary outcome measures were motor, psychological, and social functioning. | 24 | Results in press. Early DBS shows advantage over medical treatment (personal communication, G. Deuschl, 2012). | |

ADL = activities of daily living; DBS = deep brain stimulation; PD = Parkinson disease; RCT = randomized clinical trial; STN = subthalamic nucleus; UPDRS = Unified Parkinson Disease Rating Scale.

FIGURE 1.

Treatment pathways in Parkinson disease (PD) and the potential role of deep brain stimulation (DBS). The optimal treatment of PD evolves as the disease progresses. The figure shows a generally accepted paradigm for management (brown boxes). The current role for DBS is most commonly accepted for those PD patients with significant motor complications that limit quality of life, but whose other features (eg, L-dopa responsiveness, intact cognition) render them suitable for consideration of this therapy. We propose that DBS be considered earlier in the therapeutic program of PD (green boxes), when patients might be able to derive greater long-term benefit. COMT = catechol-O-methyltransferase; MAO-B = monoamine oxidase B. [Color figure can be viewed in the online issue, which is available at http://www.annalsofneurology.org.]

There are a number of small anecdotal reports of DBS in early PD. For instance, a class 4 evaluation of bilateral STN stimulation performed in the earlier and later stages of PD, defined by disease duration and function, found that earlier DBS resulted in significantly greater postoperative independence as assessed by ADL.79 The multicenter EARLYSTIM trial comparing early DBS a mean of 7.5 years after diagnosis with best medical therapy80 has recently been published.81 STN was performed in 120 PD patients and compared to 127 patients in the medical therapy group. Mean age was 52 years, L-dopa therapy duration was 4.9 years, and fluctuations and/or dyskinesias had been present for 1.5 or 1.7 years, respectively. The primary endpoint was quality of life at 24 months as determined by the Parkinson's Disease Questionnaire (PDQ)−39, and showed an 8-point difference in favor of the STN group. PDQ-39 benefit in the STN group was evident at 5 months, with a 10-point improvement over medical therapy. There were additional benefits for the STN group in relation to motor function, ADL, and L-dopa–related motor complications. Serious adverse events occurred in 54.8% of the STN group (17.7% device-related) and 44.1% of the medical group. Those related to surgery or the device resolved completely with the exception of 1 that left a cutaneous scar. There were 2 suicides in the STN group and 1 in the medical therapy group, but overall there was no difference between the groups in suicidal behavior.

Evidence for the economic benefit of early DBS comes from a recent Markov state transition decision analytic model of STN DBS applied at an early versus delayed stage, defined by off time.82 This analysis concluded that early DBS increases quality-adjusted life years and reduces treatment costs; the need for further clinical trials in this area was supported. There may be scope to identify specific subgroups that are likely to have long-term symptomatic benefit from early DBS and for these patients to be referred to a specialist center for evaluation. From the evidence available, such groups may include young patients, those with rapidly progressive disease, those with treatment-related complications, those who have been confirmed to have sustained L-dopa–responsive pathology with other forms of PD excluded, medication-intolerant patients, those with unilateral disease, and active elderly patients.82,83

One of the longest follow-up studies of DBS in PD showed that at 10 years the effect of DBS was maintained in all motor domains except axial symptoms, which negated some of the overall motor benefit.39 Benefits in the domain of ADL may not be maintained beyond 9 years of follow-up.38 There is some evidence of late cognitive decline in patients with DBS, but this may simply reflect disease progression.14,38 However, there have been no comparisons to best medical therapy with respect to the changes in ADL function expected over this period of time.

Evidence for Earlier Use of DBS for Disease Modification in PD

Slowing the progression of PD is a major goal of therapy, but presents obvious significant challenges, mainly related to the complex etiology of the disease.84–86 There has been some evidence suggesting that STN DBS may have a disease-modifying role in animal models of PD, but a major limitation of these results is lack of reproducibility in humans. This may in turn be due to the limitations of the 6-hydroxydopamine (6-OHDA) and 1-methyl-4-phenyl-1,2,3,6-tetrahydropyridine (MPTP) models of PD in reflecting the pathophysiological mechanisms, the differing time course of disease development, and the effects of medication in humans.

In a 6-OHDA rodent model of PD with up to 75% of nigral neurons lost and up to 93% reduction in dopamine levels, STN DBS prevented further neuronal loss.87 This study also demonstrated that despite apparent neuroprotection, striatal dopamine levels were not increased. The authors highlight the role of this study in suggesting that DBS may have benefit in early PD when fewer neurons have been lost. There is no research yet into the critical mass of neurons at which DBS might be most effective and below which it could have limited scope to work. The neuroprotective effect of STN DBS in the rat model has also been demonstrated by other groups88,89; STN lesioning in the 6-OHDA rat model of PD resulted in ⅓ of nigral neurons being preserved.90

In the hemiparkinsonian MPTP primate model, STN DBS significantly increases striatal dopamine levels, attenuates loss of dopaminergic cells in the periaqueductal gray matter of primates, and leads to a mean of 20% more nigral neurons with symptomatic improvement.91–93 The mechanisms by which DBS could mediate neuroprotection are unknown, but have been proposed to include a reduction in excitotoxically induced damage.92

Because advanced PD is associated with probably >85% nigral cell death and early PD with approximately 50% cell death,94 it is probable that significant changes to neural networks have already been established even before the patient presents clinically.95–100 It is possible that DBS applied to mild rather than advanced PD will have a head start, because there are more neurons available at baseline to act upon. There is a parallel hypothesis to this in terms of early initiation of medical therapy in PD and its potential for beneficial plastic changes in basal ganglia circuitry.101

There are few human studies examining whether DBS has any disease-modifying effects in PD. An 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose (FDG) PET study in 17 patients showed no slowing of the progression of PD, suggesting that DBS may not afford any neuroprotection.102,103 More optimistic results come from another study using [11C] raclopride PET, which found that STN DBS raised striatal dopamine levels and further increased levels after L-dopa administration in patients experiencing the wearing off phenomenon.104 This study may have been limited because duration of DBS withdrawal before clinical evaluation was only 30 to 40 minutes. However, PD signs may become progressively worse over a span of hours after switching off the stimulation,105 and sudden failure of the DBS battery in PD patients has been reported as an emergency condition, due to severe relapse of symptoms.106

If any neuroprotective properties of DBS are limited to dopaminergic neurons, L-dopa–resistant motor and nonmotor symptoms are unlikely to be DBS-responsive.107 However, there is recent evidence on FDG PET in advanced PD that DBS-induced effects of metabolism extend to include cerebellar and limbic nuclei and frontal lobes.108,109 This suggests that DBS may modulate nondopaminergic networks, which may in the long term impact nonmotor clinical features of PD.

Nevertheless, the most recent long-term follow-up studies with 5 to 10 years of continuous STN DBS have failed to indicate a nondopaminergic neuroprotective benefit from DBS. Patients who had STN DBS in situ for 8 to 10 years had maintenance of motor benefits and functional improvement despite reduction in L-dopa dose, but had significant decline in postural stability, axial symptoms, and a nonsignificant decline in cognition.39 The conclusions from long-term follow-up studies suggest that the greatest sources of disability in late-stage PD, including drug-resistant axial motor features, psychiatric disorders, dysautonomia, and cognitive decline, are probably not significantly modified by DBS.110 An editorial discussing a 9-year follow-up of DBS in PD highlights that its role may shift if there is success in the development of disease-modifying medical therapies that treat dopamine deficiency but do not induce the disabling motor complications that currently are the strongest indication for DBS.111

Future Directions

Evidence is emerging that DBS may be suitable for use in less advanced PD, at an earlier stage of disease than it is currently commonly applied. This proposal is supported by the results of the EARLYSTIM trial. DBS should be considered and discussed with the patient when the burden of the disease begins to have an impact on the quality of life and medical therapy fails to provide adequate control or causes significant side effects. The improving short- and long-term safety profile of DBS makes earlier application a realistic possibility; centers that might consider this approach must conduct regular prospective evaluations of their outcomes, including both clinical benefit and adverse effects.

Conclusion

The treatment of PD has evolved significantly since the introduction of L-dopa 40 years ago. Advances in our understanding of the natural history of the disease and the therapies available for its management require us periodically to reappraise our strategies for patients.91 Advances in surgical techniques, brain imaging, and device design have brought us to the position where we should re-evaluate which patients we can consider for DBS and at what point in their disease this is offered. We may be entering a period when DBS is considered earlier in the disease course than has hitherto been the case.

Potential Conflicts of Interest

E.M.: consultancy, Medtronic; grants/grants pending, St. Jude, CIHR, CurePSP; speaking fees, Medtronic. A.E.L.: consultancy, Biovail, Ceregene, Novartis, Merck Serono, Solvay, Tea, Abbott, Allon Therapeutics, AstraZeneca, Eisai, GSK, MSD, BMS, Medtronic; expert testimony, welding rod; grants/grants pending, Ontario Problem Gambling Research Centre, Canadian Institutes of Health Research, Michael J. Fox Foundation, National Parkinson Foundation; royalties, Saunders, Wiley-Blackwell, Johns Hopkins Press, Cambridge University Press. A.H.V.S.: royalties, Elsevier, Wiley-Blackwell, OUP; paid educational presentations, BI, GSK, Teva-Lundbeck, Orion-Novartis, Merck, UCB.

References

- 1.Twelves D, Perkins KS, Counsell C. Systematic review of incidence studies of Parkinson's disease. Mov Disord. 2003;18:19–31. doi: 10.1002/mds.10305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wickremaratchi MM, Ben-Shlomo Y, Morris HR. The effect of onset age on the clinical features of Parkinson's disease. Eur J Neurol. 2009;16:450–456. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-1331.2008.02514.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dorsey ER, Constantinescu R, Thompson JP, et al. Projected number of people with Parkinson disease in the most populous nations, 2005 through 2030. Neurology. 2007;68:384–386. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000247740.47667.03. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Findley LJ. The economic impact of Parkinson's disease. Parkinsonism Relat Disord. 2007;13(suppl):S8–S12. doi: 10.1016/j.parkreldis.2007.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Vossius C, Nilsen OB, Larsen JP. Parkinson's disease and nursing home placement: the economic impact of the need for care. Eur J Neurol. 2009;16:194–200. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-1331.2008.02380.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Winter Y, Balzer-Geldsetzer M, Spottke A, et al. Longitudinal study of the socioeconomic burden of Parkinson's disease in Germany. Eur J Neurol. 2010;17:1156–1163. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-1331.2010.02984.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Weintraub D, Comella CL, Horn S. Parkinson's disease—Part 1: Pathophysiology, symptoms, burden, diagnosis, and assessment. Am J Manag Care. 2008;14:S40–S48. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chen JJ. Parkinson's disease: health-related quality of life, economic cost, and implications of early treatment. Am J Manag Care. 2010;16(suppl Implications):S87–S93. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chaudhuri KR, Healy DG, Schapira AH. Non-motor symptoms of Parkinson's disease: diagnosis and management. Lancet Neurol. 2006;5:235–245. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(06)70373-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Deuschl G, Schade-Brittinger C, Krack P, et al. A randomized trial of deep-brain stimulation for Parkinson's disease. N Engl J Med. 2006;355:896–908. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa060281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Okun MS, Fernandez HH, Wu SS, et al. Cognition and mood in Parkinson's disease in subthalamic nucleus versus globus pallidus interna deep brain stimulation: the COMPARE trial. Ann Neurol. 2009;65:586–595. doi: 10.1002/ana.21596. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Weaver FM, Follett K, Stern M, et al. Bilateral deep brain stimulation vs best medical therapy for patients with advanced Parkinson disease: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2009;301:63–73. doi: 10.1001/jama.2008.929. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Follett KA, Weaver FM, Stern M, et al. Pallidal versus subthalamic deep-brain stimulation for Parkinson's disease. N Engl J Med. 2010;362:2077–2091. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0907083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kleiner-Fisman G, Herzog J, Fisman DN, et al. Subthalamic nucleus deep brain stimulation: summary and meta-analysis of outcomes. Mov Disord. 2006;21(suppl 14):S290–S304. doi: 10.1002/mds.20962. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Volkmann J, Allert N, Voges J, et al. Long-term results of bilateral pallidal stimulation in Parkinson's disease. Ann Neurol. 2004;55:871–875. doi: 10.1002/ana.20091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Houeto JL, Damier P, Bejjani PB, et al. Subthalamic stimulation in Parkinson disease: a multidisciplinary approach. Arch Neurol. 2000;57:461–465. doi: 10.1001/archneur.57.4.461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Weaver FM, Follett KA, Stern M, et al. Randomized trial of deep brain stimulation for Parkinson disease: thirty-six-month outcomes. Neurology. 2012;79:55–65. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e31825dcdc1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Evidente VG, Premkumar AP, Adler CH, et al. Medication dose reductions after pallidal versus subthalamic stimulation in patients with Parkinson's disease. Acta Neurol Scand. 2011;124:211–214. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0404.2010.01455.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Moro E, Lozano AM, Pollak P, et al. Long-term results of a multicenter study on subthalamic and pallidal stimulation in Parkinson's disease. Mov Disord. 2010;25:578–586. doi: 10.1002/mds.22735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lang AE, Widner H. Deep brain stimulation for Parkinson's disease: patient selection and evaluation. Mov Disord. 2002;17(suppl 3):S94–S101. doi: 10.1002/mds.10149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Morgante L, Morgante F, Moro E, et al. How many parkinsonian patients are suitable candidates for deep brain stimulation of subthalamic nucleus? Results of a questionnaire. Parkinsonism Relat Disord. 2007;13:528–531. doi: 10.1016/j.parkreldis.2006.12.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.NICE. Deep brain stimulation for Parkinson's disease. Available at: http:/www.nice.org.uk/IPG019.

- 23.Lang AE, Houeto JL, Krack P, et al. Deep brain stimulation: preoperative issues. Mov Disord. 2006;21(suppl 14):S171–S196. doi: 10.1002/mds.20955. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.NICE. Parkinson's disease. Available at: http:/www.nice.org.uk/CG035.

- 25.Fox SH, Katzenschlager R, Lim SY, et al. The Movement Disorder Society Evidence-Based Medicine Review Update: Treatments for the motor symptoms of Parkinson's disease. Mov Disord. 2011;26(suppl 3):S2–S41. doi: 10.1002/mds.23829. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Koller WC, Tse W. Unmet medical needs in Parkinson's disease. Neurology. 2004;62:S1–S8. doi: 10.1212/wnl.62.1_suppl_1.s1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Poewe W. Treatments for Parkinson disease—past achievements and current clinical needs. Neurology. 2009;72:S65–S73. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e31819908ce. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hatano T, Kubo SI, Shimo Y, et al. Unmet needs of patients with Parkinson's disease: interview survey of patients and caregivers. J Int Med Res. 2009;37:717–726. doi: 10.1177/147323000903700315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Schapira AH. Disease modification in Parkinson's disease. Lancet Neurol. 2004;3:362–368. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(04)00769-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Moro E, Lang AE. Criteria for deep-brain stimulation in Parkinson's disease: review and analysis. Expert Rev Neurother. 2006;6:1695–1705. doi: 10.1586/14737175.6.11.1695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bronstein JM, Tagliati M, Alterman RL, et al. Deep brain stimulation for Parkinson disease: an expert consensus and review of key issues. Arch Neurol. 2011;68:165. doi: 10.1001/archneurol.2010.260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Moro E, Allert N, Eleopra R, et al. A decision tool to support appropriate referral for deep brain stimulation in Parkinson's disease. J Neurol. 2009;256:83–88. doi: 10.1007/s00415-009-0069-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wachter T, Minguez-Castellanos A, Valldeoriola F, et al. A tool to improve pre-selection for deep brain stimulation in patients with Parkinson's disease. J Neurol. 2011;258:641–646. doi: 10.1007/s00415-010-5814-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Krack P, Batir A, Van BN, et al. Five-year follow-up of bilateral stimulation of the subthalamic nucleus in advanced Parkinson's disease. N Engl J Med. 2003;349:1925–1934. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa035275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Fasano A, Romito LM, Daniele A, et al. Motor and cognitive outcome in patients with Parkinson's disease 8 years after subthalamic implants. Brain. 2010;133:2664–2676. doi: 10.1093/brain/awq221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Vitek JL, Lyons KE, Bakay R, et al. Standard guidelines for publication of deep brain stimulation studies in Parkinson's disease (Guide4DBS-PD) Mov Disord. 2010;25:1530–1537. doi: 10.1002/mds.23151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wider C, Russmann H, Villemure JG, et al. Long-duration response to levodopa in patients with advanced Parkinson disease treated with subthalamic deep brain stimulation. Arch Neurol. 2006;63:951–955. doi: 10.1001/archneur.63.7.951. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zibetti M, Merola A, Rizzi L, et al. Beyond nine years of continuous subthalamic nucleus deep brain stimulation in Parkinson's disease. Mov Disord. 2011;26:2327–2334. doi: 10.1002/mds.23903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Castrioto A, Lozano AM, Poon YY, et al. Ten-year outcome of subthalamic stimulation in Parkinson disease: a blinded evaluation. Arch Neurol. 2011;68:1550–1556. doi: 10.1001/archneurol.2011.182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Follett KA, Torres-Russotto D. Deep brain stimulation of globus pallidus interna, subthalamic nucleus, and pedunculopontine nucleus for Parkinson's disease: which target? Parkinsonism Relat Disord. 2012;18(suppl 1):S165–S167. doi: 10.1016/S1353-8020(11)70051-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hariz MI, Krack P, Alesch F, et al. Multicentre European study of thalamic stimulation for parkinsonian tremor: a 6 year follow-up. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2008;79:694–699. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.2007.118653. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Fimm B, Heber IA, Coenen VA, et al. Deep brain stimulation of the subthalamic nucleus improves intrinsic alertness in Parkinson's disease. Mov Disord. 2009;24:1613–1620. doi: 10.1002/mds.22580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Halpern CH, Rick JH, Danish SF, et al. Cognition following bilateral deep brain stimulation surgery of the subthalamic nucleus for Parkinson's disease. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2009;24:443–451. doi: 10.1002/gps.2149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Nazzaro JM, Pahwa R, Lyons KE. The impact of bilateral subthalamic stimulation on non-motor symptoms of Parkinson's disease. Parkinsonism Relat Disord. 2011;17:606–609. doi: 10.1016/j.parkreldis.2011.05.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Strutt AM, Simpson R, Jankovic J, York MK. Changes in cognitive-emotional and physiological symptoms of depression following STN-DBS for the treatment of Parkinson's disease. Eur J Neurol. 2012;19:121–127. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-1331.2011.03447.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Halim A, Baumgartner L, Binder DK. Effect of deep brain stimulation on autonomic dysfunction in patients with Parkinson's disease. J Clin Neurosci. 2011;18:804–806. doi: 10.1016/j.jocn.2010.10.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Witjas T, Kaphan E, Regis J, et al. Effects of chronic subthalamic stimulation on nonmotor fluctuations in Parkinson's disease. Mov Disord. 2007;22:1729–1734. doi: 10.1002/mds.21602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.St George RJ, Carlson-Kuhta P, Burchiel KJ, et al. The effects of subthalamic and pallidal deep brain stimulation on postural responses in patients with Parkinson disease. J Neurosurg. 2012;116:1347–1356. doi: 10.3171/2012.2.JNS11847. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Rothlind JC, Cockshott RW, Starr PA, Marks WJ., Jr Neuropsychological performance following staged bilateral pallidal or subthalamic nucleus deep brain stimulation for Parkinson's disease. J Int Neuropsychol Soc. 2007;13:68–79. doi: 10.1017/S1355617707070105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Zahodne LB, Okun MS, Foote KD, et al. Greater improvement in quality of life following unilateral deep brain stimulation surgery in the globus pallidus as compared to the subthalamic nucleus. J Neurol. 2009;256:1321–1329. doi: 10.1007/s00415-009-5121-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Chan DT, Zhu XL, Yeung JH, et al. Complications of deep brain stimulation: a collective review. Asian J Surg. 2009;32:258–263. doi: 10.1016/S1015-9584(09)60404-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Voon V, Krack P, Lang AE, et al. A multicentre study on suicide outcomes following subthalamic stimulation for Parkinson's disease. Brain. 2008;131:2720–2728. doi: 10.1093/brain/awn214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Kirsch-Darrow L, Zahodne LB, Marsiske M, et al. The trajectory of apathy after deep brain stimulation: from pre-surgery to 6 months post-surgery in Parkinson's disease. Parkinsonism Relat Disord. 2011;17:182–188. doi: 10.1016/j.parkreldis.2010.12.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Porat O, Cohen OS, Schwartz R, Hassin-Baer S. Association of preoperative symptom profile with psychiatric symptoms following subthalamic nucleus stimulation in patients with Parkinson's disease. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2009;21:398–405. doi: 10.1176/jnp.2009.21.4.398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Witt K, Daniels C, Reiff J, et al. Neuropsychological and psychiatric changes after deep brain stimulation for Parkinson's disease: a randomised, multicentre study. Lancet Neurol. 2008;7:605–614. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(08)70114-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Peron J, Biseul I, Leray E, et al. Subthalamic nucleus stimulation affects fear and sadness recognition in Parkinson's disease. Neuropsychology. 2010;24:1–8. doi: 10.1037/a0017433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Demetriades P, Rickards H, Cavanna AE. Impulse control disorders following deep brain stimulation of the subthalamic nucleus in Parkinson's disease: clinical aspects. Parkinsons Dis. 2011;2011:658415. doi: 10.4061/2011/658415. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Broen M, Duits A, Visser-Vandewalle V, et al. Impulse control and related disorders in Parkinson's disease patients treated with bilateral subthalamic nucleus stimulation: a review. Parkinsonism Relat Disord. 2011;17:413–417. doi: 10.1016/j.parkreldis.2011.02.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Appleby BS, Duggan PS, Regenberg A, Rabins PV. Psychiatric and neuropsychiatric adverse events associated with deep brain stimulation: a meta-analysis of ten years' experience. Mov Disord. 2007;22:1722–1728. doi: 10.1002/mds.21551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Heo JH, Lee KM, Paek SH, et al. The effects of bilateral subthalamic nucleus deep brain stimulation (STN DBS) on cognition in Parkinson disease. J Neurol Sci. 2008;273:19–24. doi: 10.1016/j.jns.2008.06.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Alberts JL, Voelcker-Rehage C, Hallahan K, et al. Bilateral subthalamic stimulation impairs cognitive-motor performance in Parkinson's disease patients. Brain. 2008;131:3348–3360. doi: 10.1093/brain/awn238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Thobois S, Ardouin C, Lhommée E, et al. Non-motor dopamine withdrawal syndrome after surgery for Parkinson's disease: predictors and underlying mesolimbic denervation. Brain. 2010;133:1111–1127. doi: 10.1093/brain/awq032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Videnovic A, Metman LV. Deep brain stimulation for Parkinson's disease: prevalence of adverse events and need for standardized reporting. Mov Disord. 2008;23:343–349. doi: 10.1002/mds.21753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Amara AW, Watts RL, Walker HC. The effects of deep brain stimulation on sleep in Parkinson's disease. Ther Adv Neurol Disord. 2011;4:15–24. doi: 10.1177/1756285610392446. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Shields DC, Lam S, Gorgulho A, et al. Eyelid apraxia associated with subthalamic nucleus deep brain stimulation. Neurology. 2006;66:1451–1452. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000210693.13093.c8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Doshi P, Bhargava P. Hypersexuality following subthalamic nucleus stimulation for Parkinson's disease. Neurol India. 2008;56:474–476. doi: 10.4103/0028-3886.44830. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Okun MS, Gallo BV, Mandybur G, et al. Subthalamic deep brain stimulation with a constant-current device in Parkinson's disease: an open-label randomised controlled trial. Lancet Neurol. 2012;11:140–149. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(11)70308-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Derost PP, Ouchchane L, Morand D, et al. Is DBS-STN appropriate to treat severe Parkinson disease in an elderly population? Neurology. 2007;68:1345–1355. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000260059.77107.c2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Williams A, Gill S, Varma T, et al. Deep brain stimulation plus best medical therapy versus best medical therapy alone for advanced Parkinson's disease (PD SURG trial): a randomised, open-label trial. Lancet Neurol. 2010;9:581–591. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(10)70093-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Dams J, Bornschein B, Reese JP, et al. Modelling the cost effectiveness of treatments for Parkinson's disease: a methodological review. Pharmacoeconomics. 2011;29:1025–1049. doi: 10.2165/11587110-000000000-00000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.McIntosh E. Perspective on the economic evaluation of deep brain stimulation. Front Integr Neurosci. 2011;5:19. doi: 10.3389/fnint.2011.00019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Valldeoriola F, Morsi O, Tolosa E, et al. Prospective comparative study on cost-effectiveness of subthalamic stimulation and best medical treatment in advanced Parkinson's disease. Mov Disord. 2007;22:2183–2191. doi: 10.1002/mds.21652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Spottke EA, Volkmann J, Lorenz D, et al. Evaluation of healthcare utilization and health status of patients with Parkinson's disease treated with deep brain stimulation of the subthalamic nucleus. J Neurol. 2002;249:759–766. doi: 10.1007/s00415-002-0711-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Fraix V, Houeto JL, Lagrange C, et al. Clinical and economic results of bilateral subthalamic nucleus stimulation in Parkinson's disease. Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2006;77:443–449. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.2005.077677. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Kahn E, D'Haese PF, Dawant B, et al. Deep brain stimulation in early stage Parkinson's disease: operative experience from a prospective randomised clinical trial. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2012;83:164–170. doi: 10.1136/jnnp-2011-300008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Schupbach WM, Maltete D, Houeto JL, et al. Neurosurgery at an earlier stage of Parkinson disease: a randomized, controlled trial. Neurology. 2007;68:267–271. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000250253.03919.fb. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Agid Y, Schupbach M, Gargiulo M, et al. Neurosurgery in Parkinson's disease: the doctor is happy, the patient less so? J Neural Transm Suppl. 2006;(70):409–414. doi: 10.1007/978-3-211-45295-0_61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Okun MS, Wu SS, Foote KD, et al. Do stable patients with a premorbid depression history have a worse outcome after deep brain stimulation for Parkinson disease? Neurosurgery. 2011;69:357–360. doi: 10.1227/NEU.0b013e3182160456. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Yamada K, Hamasaki T, Kuratsu J. Subthalamic nucleus stimulation applied in the earlier vs. advanced stage of Parkinson's disease—retrospective evaluation of postoperative independence in pursuing daily activities. Parkinsonism Relat Disord. 2009;15:746–751. doi: 10.1016/j.parkreldis.2009.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Deuschl G, Schüpbach M, Knudsen K, et al. Stimulation of the subthalamic nucleus at an earlier disease stage of Parkinson's disease: concept and standards of the EARLYSTIM-study. Parkinsonism Relat Disord. 2013;19:56–61. doi: 10.1016/j.parkreldis.2012.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Schuepbach WMM, Rau J, Knudsen K, et al. Neurostimulation for Parkinson's disease with early motor complications. N Engl J Med. 2013;368:610–622. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1205158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Espay AJ, Vaughan JE, Marras C, et al. Early versus delayed bilateral subthalamic deep brain stimulation for Parkinson's disease: a decision analysis. Mov Disord. 2010;25:1456–1463. doi: 10.1002/mds.23111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Merola A, Zibetti M, Artusi CA, et al. Subthalamic nucleus deep brain stimulation outcome in young onset Parkinson's disease: a role for age at disease onset? J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2012;83:251–257. doi: 10.1136/jnnp-2011-300470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Olanow CW, Kieburtz K, Schapira AH. Why have we failed to achieve neuroprotection in Parkinson's disease? Ann Neurol. 2008;64(suppl 2):S101–S110. doi: 10.1002/ana.21461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Obeso JA, Rodriguez-Oroz MC, Goetz CG, et al. Missing pieces in the Parkinson's disease puzzle. Nat Med. 2010;16:653–661. doi: 10.1038/nm.2165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Schapira AH, Tolosa E. Molecular and clinical prodrome of Parkinson disease: implications for treatment. Nat Rev Neurol. 2010;6:309–317. doi: 10.1038/nrneurol.2010.52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Spieles-Engemann AL, Behbehani MM, Collier TJ, et al. Stimulation of the rat subthalamic nucleus is neuroprotective following significant nigral dopamine neuron loss. Neurobiol Dis. 2010;39:105–115. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2010.03.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Maesawa S, Kaneoke Y, Kajita Y, et al. Long-term stimulation of the subthalamic nucleus in hemiparkinsonian rats: neuroprotection of dopaminergic neurons. J Neurosurg. 2004;100:679–687. doi: 10.3171/jns.2004.100.4.0679. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Harnack D, Meissner W, Jira JA, et al. Placebo-controlled chronic high-frequency stimulation of the subthalamic nucleus preserves dopaminergic nigral neurons in a rat model of progressive Parkinsonism. Exp Neurol. 2008;210:257–260. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2007.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Carvalho GA, Nikkhah G. Subthalamic nucleus lesions are neuroprotective against terminal 6-OHDA-induced striatal lesions and restore postural balancing reactions. Exp Neurol. 2001;171:405–417. doi: 10.1006/exnr.2001.7742. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Zhao XD, Cao YQ, Liu HH, et al. Long term high frequency stimulation of STN increases dopamine in the corpus striatum of hemiparkinsonian rhesus monkey. Brain Res. 2009;1286:230–238. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2009.06.069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Wallace BA, Ashkan K, Heise CE, et al. Survival of midbrain dopaminergic cells after lesion or deep brain stimulation of the subthalamic nucleus in MPTP-treated monkeys. Brain. 2007;130:2129–2145. doi: 10.1093/brain/awm137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Shaw VE, Keay KA, Ashkan K, et al. Dopaminergic cells in the periaqueductal grey matter of MPTP-treated monkeys and mice; patterns of survival and effect of deep brain stimulation and lesion of the subthalamic nucleus. Parkinsonism Relat Disord. 2010;16:338–344. doi: 10.1016/j.parkreldis.2010.02.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Charles PD, Gill CE, Davis TL, et al. Is deep brain stimulation neuroprotective if applied early in the course of PD? Nat Clin Pract Neurol. 2008;4:424–426. doi: 10.1038/ncpneuro0848. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Wichmann T, DeLong MR. Deep brain stimulation for neurologic and neuropsychiatric disorders. Neuron. 2006;52:197–204. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2006.09.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Wichmann T, Bergman H, DeLong MR. The primate subthalamic nucleus. III. Changes in motor behavior and neuronal activity in the internal pallidum induced by subthalamic inactivation in the MPTP model of parkinsonism. J Neurophysiol. 1994;72:521–530. doi: 10.1152/jn.1994.72.2.521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Lin TP, Carbon M, Tang C, et al. Metabolic correlates of subthalamic nucleus activity in Parkinson's disease. Brain. 2008;131:1373–1380. doi: 10.1093/brain/awn031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Eckert T, Tang C, Eidelberg D. Assessment of the progression of Parkinson's disease: a metabolic network approach. Lancet Neurol. 2007;6:926–932. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(07)70245-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Asanuma K, Tang C, Ma Y, et al. Network modulation in the treatment of Parkinson's disease. Brain. 2006;129:2667–2678. doi: 10.1093/brain/awl162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Amtage F, Henschel K, Schelter B, et al. High functional connectivity of tremor related subthalamic neurons in Parkinson's disease. Clin Neurophysiol. 2009;120:1755–1761. doi: 10.1016/j.clinph.2009.06.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Schapira AH, Obeso J. Timing of treatment initiation in Parkinson's disease: a need for reappraisal? Ann Neurol. 2006;59:559–562. doi: 10.1002/ana.20789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Warnke PC. STN stimulation and neuroprotection in Parkinson's disease—when beautiful theories meet ugly facts. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2005;76:1186–1187. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.2004.061481. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Hilker R, Portman AT, Voges J, et al. Disease progression continues in patients with advanced Parkinson's disease and effective subthalamic nucleus stimulation. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2005;76:1217–1221. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.2004.057893. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Nimura T, Yamaguchi K, Ando T, et al. Attenuation of fluctuating striatal synaptic dopamine levels in patients with Parkinson disease in response to subthalamic nucleus stimulation: a positron emission tomography study. J Neurosurg. 2005;103:968–973. doi: 10.3171/jns.2005.103.6.0968. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Temperli P, Ghika J, Villemure JG, et al. How do parkinsonian signs return after discontinuation of subthalamic DBS? Neurology. 2003;60:78–81. doi: 10.1212/wnl.60.1.78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Hariz MI, Johansson F. Hardware failure in parkinsonian patients with chronic subthalamic nucleus stimulation is a medical emergency. Mov Disord. 2001;16:166–168. doi: 10.1002/1531-8257(200101)16:1<166::aid-mds1031>3.0.co;2-s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Fahn S. How do you treat motor complications in Parkinson's disease: medicine, surgery, or both? Ann Neurol. 2008;64(suppl 2):S56–S64. doi: 10.1002/ana.21453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Hilker R, Voges J, Weisenbach S, et al. Subthalamic nucleus stimulation restores glucose metabolism in associative and limbic cortices and in cerebellum: evidence from a FDG-PET study in advanced Parkinson's disease. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2004;24:7–16. doi: 10.1097/01.WCB.0000092831.44769.09. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Kalbe E, Voges J, Weber T, et al. Frontal FDG-PET activity correlates with cognitive outcome after STN-DBS in Parkinson disease. Neurology. 2009;72:42–49. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000338536.31388.f0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Hely MA, Reid WG, Adena MA, et al. The Sydney multicenter study of Parkinson's disease: the inevitability of dementia at 20 years. Mov Disord. 2008;23:837–844. doi: 10.1002/mds.21956. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Obeso JA, Olanow W. Deep brain stimulation for Parkinson's disease: thinking about the long-term in the short-term. Mov Disord. 2011;26:2303–2304. doi: 10.1002/mds.24036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Hamani C, Richter E, Schwalb JM, Lozano AM. Bilateral subthalamic nucleus stimulation for Parkinson's disease: a systematic review of the clinical literature. Neurosurgery. 2005;56:1313–1321. doi: 10.1227/01.neu.0000159714.28232.c4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Shichi T, Okiyama R, Yokochi F, et al. Unilateral subthalamic stimulation for early-stage Parkinson's disease [in Japanese] No To Shinkei. 2005;57:495–498. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]