Abstract

Background

Surgical mortality results are increasingly being reported and published in the public domain as indicators of surgical quality. This study examined how mortality outlier status at 90 days after colorectal surgery compares with mortality at 30 days and subsequent intervals in the first year after surgery.

Methods

All adults undergoing elective and emergency colorectal resection between April 2001 and February 2007 in English National Health Service (NHS) Trusts were identified from administrative data. Funnel plots of postoperative case mix-adjusted institutional mortality rate against caseload were created for 30, 90, 180 and 365 days. High- or low-mortality unit status of individual Trusts was defined as breaching upper or lower third standard deviation confidence limits on the funnel plot for 90-day mortality.

Results

A total of 171 688 patients from 153 NHS Trusts were included. Some 14 537 (8·5 per cent) died within 30 days of surgery, 19 466 (11·3 per cent) within 90 days, 23 942 (13·9 per cent) within 180 days and 31 782 (18·5 per cent) within 365 days. Eight institutions were identified as high-mortality units, including all four units with high outlying status at 30 days. Twelve units were low-mortality units, of which six were also low outliers at 30 days. Ninety-day mortality correlated strongly with later mortality results (rs = 0·957, P < 0·001 versus 180-day mortality; rs = 0·860, P < 0·001 versus 365-day mortality).

Conclusion

Extending mortality reporting to 90 days identifies a greater number of mortality outliers when compared with the 30-day death rate. Ninety-day mortality is proposed as the preferred indicator of perioperative outcome for local analysis and public reporting.

Introduction

Colorectal surgery is commonly performed for benign and malignant disease, and carries a significant risk of death or complication1–3. Colorectal cancer is the third most common cancer diagnosed in the UK4 and surgery is the main treatment. Outcomes, such as mortality and morbidity rates, are often used as indicators of care quality.

Perhaps the earliest public use of outcome data began in America in the 1980s5. Measures of system performance, such as waiting times for surgery, are currently published in a number of other countries6–8. Publication of more specific outcomes is an area of ongoing development internationally, for example in the National Health Service (NHS) in England9. It is therefore important to explore how different mortality measures may affect the identification of units with high or low death rates.

Thirty-day mortality has conventionally been used to reflect perioperative outcome. Published 30-day and 1-year mortality rates after colorectal surgery range from 3·0 to 4·9 per cent, and from 8·8 to 12·4 per cent, respectively10–12. High mortality beyond 30 days highlights the importance of considering alternative periods for mortality reporting.

It is not known whether lengthening follow-up for analysis of postoperative deaths from 30 to 90 days results in the identification of a different group of units with outlying results. Neither has the relationship between high or low mortality rates at 90 days and death rates at 180 and 365 days been studied in the literature. It is also important to examine metrics in different contexts, mindful of changes in practice over time. This study examined the relationship between mortality metrics during the first year after colorectal surgery, using national, routinely collected, data for England between 2001 and 2007.

Methods

Ethical approval for the study was obtained from the local research ethics committee.

Data sources

English NHS hospitals mandatorily submit data for all inpatient activity to the Hospital Episode Statistics (HES) database. This includes International Classification of Diseases, tenth revision (ICD-10)13 diagnosis codes and Office of Population Censuses and Surveys Classification of Interventions and Procedures, version 4.4 (OPCS-4)14 procedure codes with associated dates. The NHS Information Centre links HES and statutory records of death to establish whether a patient died after surgery. From this database, patients aged 18 years or more undergoing colorectal resection between 1 April 2001 and 28 February 2007 were selected for inclusion and grouped according to OPCS codes for colonic or rectal resection (Table 1).

Table 1.

Procedures included in each group for regression modelling

| Procedure group | Procedures included, with OPCS-4 codes |

|---|---|

| Subtotal/total colectomy | Subtotal colectomy (H29) |

| Total colectomy (H05) | |

| Panproctocolectomy (H04) | |

| Right colectomy | Right hemicolectomy (H07) |

| Extended right hemicolectomy (H06) | |

| Transverse colectomy (H08) | |

| Left colectomy | Left hemicolectomy (H09) |

| Sigmoid colectomy (H10) | |

| Rectal resection | Anterior resection (H33·2–33·4, H33·6, H33·8–33·9) |

| Abdominoperineal resection (H33·1) | |

| Hartmann's procedure (H33·5) |

OPCS-4, Office of Population Censuses and Surveys Classification of Interventions and Procedures, version 4·4.

Data processing

Using anonymized patient identifiers, the data were processed to eliminate duplications of records and to identify the first major resection (when a patient underwent more than one major procedure). Trusts performing surgery on a selected population (for example, children or women only) or fewer than ten times during the study period were excluded from analysis. This included cardiothoracic, orthopaedic, paediatric, women's health, and reconstructive and rehabilitative NHS Trusts.

For risk adjustment a number of patient-, condition- and procedure-related variables were derived. Age was coded into four groups: less than 55 years, 55–69 years, 70–79 years, and 80 years or above. Charlson co-morbidity index scores were derived from secondary ICD-10 diagnosis codes and grouped as follows: 0, 1–2, 3–5 and 6 or above. The primary colorectal diagnosis was classified as malignant or benign. Admissions were coded as elective or non-elective. Operative procedures were grouped as shown in Table 1. Use of laparoscopy was derived from OPCS-4 codes Y058, Y752 and Y714. Year of procedure was coded as a categorical variable to facilitate adjustment for any improvement in results over time. All-cause mortality was coded as a binary variable at various time points: 30, 90, 180 and 365 days.

Statistical analysis

Analyses were undertaken using SPSS® version 20.0 (IBM, Armonk, New York, USA). Cohort characteristics were assessed for similarity using the χ2 test for all categorical variables. Variables with P < 0·100 on univariable analysis were included in the risk adjustment model. Case mix adjustment was performed using binary logistic regression for each mortality period with the following categorical co-variables, provided they met inclusion criteria: age group, sex, Charlson co-morbidity index group, admission type, diagnosis, procedure type, surgical approach (open or laparoscopic) and year of procedure. Observed mortality and predicted probabilities of death were aggregated by provider to calculate observed and expected mortality rates for the entire study period. The observed-to-expected (O/E) mortality ratio was multiplied by the national mortality rate and each unit's caseload to obtain a Trust-level risk-adjusted mortality for the entire study period. Model fit was assessed using the receiver operating characteristic (ROC) function.

Funnel plots of risk-adjusted mortality rate against caseload were generated for each postoperative time period using the online tool provided by the Public Health Observatories' Analytical Tools for Public Health: Funnel plot for proportions and percentages (http://www.apho.org.uk/resource/view.aspx?RID=39403). Pseudonymized providers were identified across the funnel plots to assess for changes in position relative to 99·7 and 95 per cent control limits. Provider-level O/E mortality ratios across the time periods were tested for non-parametric correlation using Spearman's rank correlation coefficient.

Results

Cohort characteristics

A total of 171 688 patients underwent a primary colorectal resection in 153 NHS Trusts that met the inclusion and exclusion criteria. Some 112 557 operations (65·6 per cent) were performed on an elective basis, 107 780 (62·8 per cent) for malignant disease. In all, 5566 procedures (3·2 per cent) were performed laparoscopically. A comprehensive cohort summary is presented in Table S1 (supporting information).

Mortality rates

Of the 171 688 patients, 14 537 (8·5 per cent) died within 30 days of surgery. At 90 days, 19 466 (11·3 per cent) had died, increasing to 23 942 (13·9 per cent) and 31 782 (18·5 per cent) at 180 and 365 days respectively.

Factors associated with mortality

On univariable analysis, all co-variables were correlated significantly with mortality (data not shown). Multivariable logistic regression results for each postoperative time period are shown in Table S2 (supporting information). Across periods, increased mortality was associated significantly with increasing age, increasing co-morbidity score, non-elective surgery and benign diagnosis. Reduced mortality was significantly associated with female sex, operations other than total/subtotal colectomy, laparoscopic surgery and later year of operation. The models yielded satisfactory measures of fit (c-statistic range 0·758–0·809).

Relationship between mortality time periods

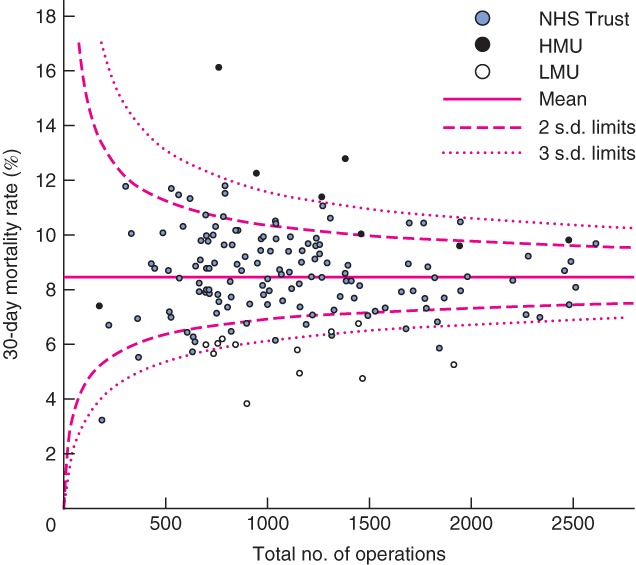

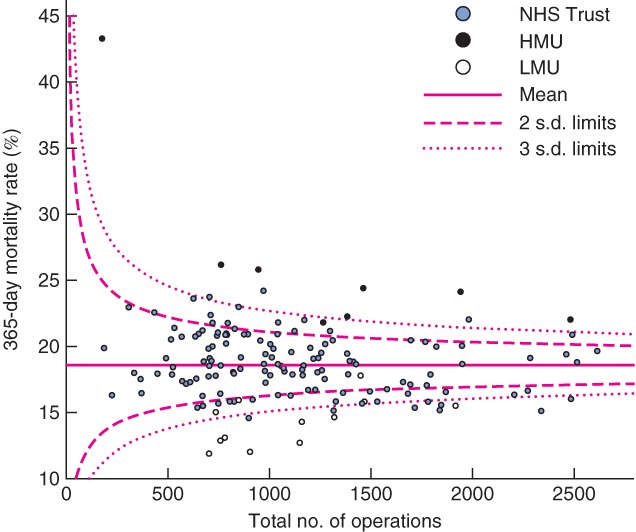

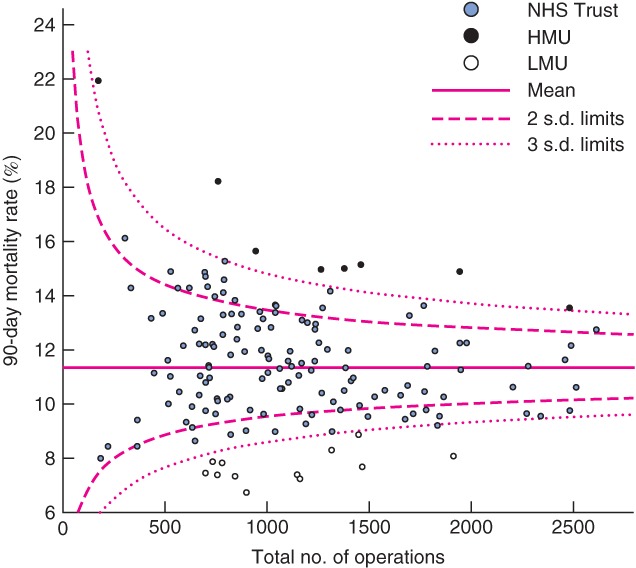

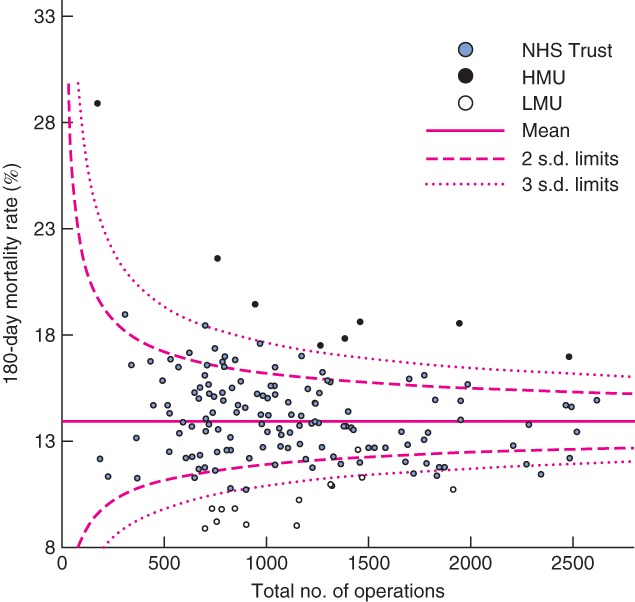

A Trust was considered an outlier for mortality if its risk-adjusted death rate was more than three standard deviations (s.d.) from the mean. Trusts could be outliers for mortality at any of the postoperative time points analysed. High- or low-mortality unit (HMU/LMU) status was defined specifically as any Trust with high or low outlying mortality at 90 days. Figs 1-4 show funnel plots of mortality against caseload for each postoperative time period.

Fig. 1.

Funnel plot of risk-adjusted postoperative mortality against total caseload by Trust from 0 to 30 days (90-day mortality outliers marked). HMU, high-mortality unit; LMU, low-mortality unit

Fig. 4.

Funnel plot of risk-adjusted postoperative mortality against total caseload by National Health Service (NHS) Trust from 0 to 365 days (90-day mortality outliers marked). HMU, high-mortality unit; LMU, low-mortality unit

Fig. 2.

Funnel plot of risk-adjusted postoperative mortality against total caseload by National Health Service (NHS) Trust from 0 to 90 days (90-day mortality outliers marked). HMU, high-mortality unit; LMU, low-mortality unit

At 30 days, four Trusts were high-mortality outliers; all of these were HMUs. Of the remaining four HMUs, three were close to the upper 95 per cent control limit (2 above, 1 below) and one unit was within control limits, just below average for mortality (Fig. 1). Of the 12 LMUs, six were low-mortality outliers for 30-day mortality. Of the remaining six LMUs, all had mortality rates below the 95 per cent control limit at 30 days. Two further Trusts were low-mortality outliers at 30 days but were not identified as LMUs.

At 180 and 365 days, increased variation in mortality was seen, with increasing numbers of outliers beyond the 95 and 99·7 per cent control limits (Table 2). At 180 days, all HMUs were above the third s.d. control limits, with no new outliers identified (Fig. 3). Eleven LMUs were low-mortality outliers at 180 days. The 12th LMU had below-average mortality, within two s.d. of the national mean. A further four units not identified as LMUs had low outlying mortality at 180 days. At 365 days, seven of eight HMUs had high outlying mortality, whereas mortality for the eighth HMU was between 95 and 99·7 per cent control limits (Fig. 4). Eight of 12 LMUs had mortality rates below the 99·7 per cent control limits. Of the remaining four LMUs, three were more the two s.d. below the mean for mortality, and one was within 95 per cent control limits.

Table 2.

Total number of Trusts identified as outliers for mortality according to varying definitions of outlier status

| Follow-up period (days) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0–30 | 0–90 | 0–180 | 0–365 | |

| Outside 3 s.d. | 12 | 20 | 23 | 25 |

| HMU | 4 | 8 | 8 | 10 |

| LMU | 8 | 12 | 15 | 15 |

| Outside 2 s.d. | 49 | 54 | 50 | 55 |

| HMU | 21 | 27 | 23 | 22 |

| LMU | 28 | 27 | 27 | 33 |

Outlier definition was varied by follow-up period and by number of standard deviations (s.d.) from mean mortality. HMU, high-mortality unit; LMU, low-mortality unit.

Fig. 3.

Funnel plot of risk-adjusted postoperative mortality against total caseload by National Health Service (NHS) Trust from 0 to 180 days (90-day mortality outliers marked). HMU, high-mortality unit; LMU, low-mortality unit

There was good correlation for mortality rates across time periods calculated for all 153 Trusts (Table 3). The strongest overall correlation with other follow-up periods was observed for 0–90-day and 0–180-day O/E mortality ratios.

Table 3.

Spearman's correlation coefficient between observed-to-expected mortality ratios across varying follow-up periods for all Trusts

| Mortality period for comparison | 0–90 days | 0–180 days | 0–365 days | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| rs | P* | rs | P* | rs | P* | |

| 0–30 days | 0·924 | < 0·001 | 0·853 | < 0·001 | 0·735 | < 0·001 |

| 0–90 days | 0·957 | < 0·001 | 0·860 | < 0·001 | ||

| 0–180 days | 0·933 | < 0·001 | ||||

Two-tailed t test.

Discussion

These results confirm previous findings10–12 of a significant burden of mortality beyond 30 days after surgery. Twice the number of high outlying units was identified at 90 days compared with 30 days, including all 30-day high outliers. High outlying mortality at 90 days was associated with high mortality rates at 180 and 365 days after surgery. Low outlying mortality at 90 days was also robust across time periods.

The findings of this study must be considered in the light of its limitations. Potential problems with the quality of administrative data and their use for non-administrative purposes have been considered previously15, although their validity for clinical research has been demonstrated16,17. Furthermore, alternatives such as voluntary data are not problem-free18–20. Stage of disease was not available for inclusion in multivariable models for patients with cancer. However, although stage may strongly influence later survival, it may be argued that death directly due to cancer within 90 days of resectional surgery could be considered a failure of surgical care. Although elective and non-elective patients may represent different populations, the regression model adjusted for this, as performed in other studies of postoperative outcome21–23. Other unmeasured confounding variables may have influenced mortality rates. The study examined all-cause mortality. Follow-up over longer periods may result in inclusion of increasing numbers of deaths from unrelated factors. There have been changes in routine colorectal practice since 2007, such as increased use of laparoscopy24,25, and the recommendation and implementation of enhanced recovery programmes26,27. Some28–31 have shown no association between these changes and death rates, whereas others10,32 have shown an association between laparoscopy and reduced mortality. To influence the differences between 30- and 90-day mortality, these changes would need to have a differential effect on death between these two time periods. Although this seems unlikely, the authors intend to repeat the current analysis on a contemporary data set.

The mortality rates presented are high, with wide variation and a steady reduction over time. Non-elective colorectal surgery is associated with a high death rate1,12,33. The relatively large proportion of non-elective surgery in this cohort significantly influenced the average mortality rates, differentiating this study from others reporting 30-day and 1-year mortality10–12. Wide variation has been documented for a number of colorectal outcome measures in other publications21–23,34 and has not yet been explained adequately. Falling postoperative mortality has been observed after colorectal cancer surgery21, as well as other malignant and benign operative procedures35,36. However, other research suggests that this may not apply to all colorectal surgery, such as non-elective37 or inflammatory bowel38 procedures. Trends in mortality over time should be studied further.

A greater number of mortality outliers were identified 90 days after surgery than at 30 days. The underlying reasons for this are not clear. As 90-day mortality captures more deaths than in-hospital mortality39, postdischarge deaths, with or without readmission, must contribute to this outcome. This does not, however, explain changes in relative performance. Some authors40,41 have described problems relating outcomes to quality of care, but others42–45 have demonstrated an association between the two. The authors suggest that development of HMU status after 30 postoperative days may relate to a number of factors: unmeasured case mix variables, complication management and follow-up practices. Unmeasured factors, such as socioeconomic status, may influence outcome. Complications, such as deep vein thrombosis, may present after 30 days46. Certainly, a significant number of readmissions after colorectal surgery may occur after this interval47. Severe complications that present late may be captured only when the definition of death is extended to 90 days. Intensive postdischarge follow-up with ready access to specialist care may affect outcome. Variation in ‘failure-to-rescue’ rates (the proportion of patients dying after diagnosis of a complication) may represent differences in the effectiveness of complication management within a unit22. Ninety-day mortality may provide some reflection of the ability of a hospital to manage complications. This metric may therefore be influenced by factors outside the direct influence of the responsible consultant, such as the provision of critical care and radiology services.

One unit had below-average mortality at 30 days, but became a high outlier by the 90th postoperative day. Unadjusted mortality for this unit was initially low (2·3 per cent at 30 days), rising to within 0·5 per cent of the national mean at 365 days. The patient cohort was younger with less co-morbidity and more women, compared with the national cohort. There were also relatively more elective and malignant procedures. The risk adjustment process would calculate a lower-than-average expected mortality for such patients, resulting in this unit's HMU status.

Previous publications examining the relationship between mortality rates across different time periods for non-colorectal specialties have shown good correlation when follow-up is cumulative48,49. One colorectal paper11 assessed the correlation of mortality results between non-overlapping time periods (0–30 days, 30 days to 1 year, and 1–5 years) and found good correlation, suggesting that this represented consistent quality of care throughout follow-up.

Although low outlying mortality may be esteemed, it is unlikely to have the same implications as high outlying mortality. With public outcome reporting, it is likely that units with high mortality will be subject to increasing scrutiny by commissioners, regulators, the media and patients. High outlying mortality should not be used objectively to judge the quality of a unit. It may be considered an indicator of a possible problem with quality of perioperative care that needs further examination. This may involve a multimodal and multidisciplinary approach, including site visits, as adopted by the Keogh report50. Future study of specific causes of death may help further to explain differences in mortality results. Although high-mortality Trusts may receive the greatest attention, study of both high- and low-mortality units is needed to understand better how to minimize the risk of death after surgery.

The findings of the present study may have implications for outcomes assessment across the surgical specialties. Although the number of additional deaths observed beyond 30 days may vary by specialty, longer follow-up may allow better reflection of the outcomes of complications after other types of surgery. The findings of this study should apply across healthcare systems, as the timing of death relates primarily to the nature of the disease and patient response to treatment.

Adoption of 90-day postoperative mortality for reporting institutional outcomes in colorectal surgery identified a greater number of outliers than 30-day mortality. It successfully identified all units with high mortality at 30 days, while identifying additional HMUs. The authors suggest that this measure may provide a better reflection of perioperative outcome by allowing more time for the effects of surgical care to become manifest.

Acknowledgments

B.E.B. and C.A.V. are supported by the National Institute for Health Research. O.F. is supported by the St Mark's Association. Funders had no role in any aspect of this study.

Disclosure: The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Supporting information

Additional supporting information may be found in the online version of this article:

Table S1 Patient characteristics for whole cohort and patients dying within each postoperative time period (Word document)

Table S2 Logistic regression analysis for each postoperative time period (Word document)

References

- 1.Ingraham AM, Cohen ME, Bilimoria KY, Feinglass JM, Richards KE, Hall BL, et al. Comparison of hospital performance in nonemergency versus emergency colorectal operations at 142 hospitals. J Am Coll Surg. 2010;210:155–165. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2009.10.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.The Clinical Outcomes of Surgical Therapy Study Group. A comparison of laparoscopically assisted and open colectomy for colon cancer. N Engl J Med. 2004;350:2050–2059. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa032651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.The COlon cancer Laparoscopic or Open Resection (COLOR) Study Group. Laparoscopic surgery versus open surgery for colon cancer: short-term outcomes of a randomised trial. Lancet Oncol. 2005;6:477–484. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(05)70221-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Office for National Statistics. Cancer Incidence and Mortality in the United Kingdom, 2008–10; 2012. http://www.ons.gov.uk/ons/dcp171778_289890.pdf [accessed 13 February 2013]

- 5.DesHarnais S, McMahon LF, Wroblewski R. Measuring outcomes of hospital care using multiple risk-adjusted indexes. Health Serv Res. 1991;26:425–445. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cancer Quality Council of Ontario. Cancer System Quality Index (CSQI) 2013. http://www.csqi.on.ca [accessed 29 July 2013]

- 7.Health Department of New South Wales Government (Australia) Hospitals/Health Services. http://www.health.nsw.gov.au/hospitals/pages/default.aspx [accessed 29 July 2013]

- 8.Dr Foster. Hospital Guide. http://www.drfosterhealth.co.uk/hospital-guide/ [accessed 29 July 2013]

- 9.NHS Commissioning Board. Everyone Counts: Planning for Patients 2013/14. http://www.commissioningboard.nhs.uk/files/2012/12/everyonecounts-planning.pdf [accessed 13 March 2013]

- 10.Mamidanna R, Burns EM, Bottle A, Aylin P, Stonell C, Hanna GB, et al. Reduced risk of medical morbidity and mortality in patients selected for laparoscopic colorectal resection in England: a population-based study. Arch Surg. 2012;147:219–227. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.2011.311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zheng H, Zhang W, Ayanian JZ, Zaborski LB, Zaslavsky AM. Profiling hospitals by survival of patients with colorectal cancer. Health Serv Res. 2011;46:729–746. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6773.2010.01222.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gooiker GA, Dekker JW, Bastiaannet E, van der Geest LG, Merkus JW, van de Velde CJ, et al. Risk factors for excess mortality in the first year after curative surgery for colorectal cancer. Ann Surg Oncol. 2012;19:2428–2434. doi: 10.1245/s10434-012-2294-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.World Health Organization. International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems(10th Revision) Geneva: World Health Organization; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- 14.NHS Classifications Service. OPCS Classifications of Interventions and Procedures Version 4·4. London: The Stationery Office; 2007. NHS Connecting for Health. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Iezzoni LI. Assessing quality using administrative data. Ann Intern Med. 1997;127:666–674. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-127-8_part_2-199710151-00048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Aylin P, Bottle A, Majeed A. Use of administrative data or clinical databases as predictors of risk of death in hospital: comparison of models. BMJ. 2007;334:1044. doi: 10.1136/bmj.39168.496366.55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Raleigh VS, Cooper J, Bremner SA, Scobie S. Patient safety indicators for England from hospital administrative data: case-control analysis and comparison with US data. BMJ. 2008;337:a1702. doi: 10.1136/bmj.a1702. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lewis RS, Graham DG, Watson JD, Lunniss PJ. Learning the hard way: the importance of accurate data. Colorectal Dis. 2012;14:1015–1018. doi: 10.1111/j.1463-1318.2012.02981.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Aylin P, Lees T, Baker S, Prytherch D, Ashley S. Descriptive study comparing routine hospital administrative data with the Vascular Society of Great Britain and Ireland's National Vascular Database. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg. 2007;33:461–465. doi: 10.1016/j.ejvs.2006.10.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Almoudaris AM, Burns EM, Bottle A, Aylin P, Darzi A, Faiz O. A colorectal perspective on voluntary submission of outcome data to clinical registries. Br J Surg. 2011;98:132–139. doi: 10.1002/bjs.7301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Morris EJA, Taylor EF, Thomas JD, Quirke P, Finan PJ, Coleman MP, et al. Thirty-day postoperative mortality after colorectal cancer surgery in England. Gut. 2011;60:806–813. doi: 10.1136/gut.2010.232181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Almoudaris AM, Burns EM, Mamidanna R, Bottle A, Aylin P, Vincent C, et al. Value of failure to rescue as a marker of the standard of care following reoperation for complications after colorectal resection. Br J Surg. 2011;98:1775–1783. doi: 10.1002/bjs.7648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Burns EM, Bottle A, Aylin P, Darzi A, Nicholls RJ, Faiz O. Variation in reoperation after colorectal surgery in England as an indicator of surgical performance: retrospective analysis of Hospital Episode Statistics. BMJ. 2011;343:d4836. doi: 10.1136/bmj.d4836. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.The NHS Information Centre. National Bowel Cancer Audit; 2007. https://catalogue.ic.nhs.uk/publications/clinical/bowel/nati-clin-audi-supp-prog-bowe-canc-2007/nati-clin-audi-supp-prog-bowe-canc-2007-rep.pdf [accessed 1 August 2013]

- 25.Association of Coloproctology of Great Britain and Ireland; Royal College of Surgeons of England; The Health and Social Care Information Centre. National Bowel Cancer Audit 2012. http://www.hqip.org.uk/assets/NCAPOP-Library/NCAPOP-2012-13/Bowel-Cancer-Audit-National-Report-pub-2012.pdf [accessed 18 January 2013]

- 26.Khan S, Gatt M, Horgan A, Anderson I, MacFie J. Guideliness for Implementation of Enhanced Recovery Protocols. London: Association of Surgeons of Great Britain and Ireland; 2009. http://www.improvement.nhs.uk/enhancedrecovery2/Portals/2/RAD1526_IIPP_Dec_09.pdf [accessed 1 August 2013] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Department of Health. Enhanced Recovery Partnership Programme Report – March 2011. http://www.improvement.nhs.uk/cancer/LinkClick.aspx?fileticket=9takAGdSB14%3d&tabid=278 [accessed 1 August 2013]

- 28.Ohtani H, Tamamori Y, Arimoto Y, Nishiguchi Y, Maeda K, Hirakawa K. A meta-analysis of the short- and long-term results of randomized controlled trials that compared laparoscopy-assisted and open colectomy for colon cancer. J Cancer. 2012;3:49–57. doi: 10.7150/jca.3621. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Schwenk W, Haase O, Neudecker JJ, Müller JM. Short term benefits for laparoscopic colorectal resection. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2005;(3):CD003145. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD003145.pub2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zhuang CL, Ye XZ, Zhang XD, Chen BC, Yu Z. Enhanced recovery after surgery programs versus traditional care for colorectal surgery: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Dis Colon Rectum. 2013;56:667–678. doi: 10.1097/DCR.0b013e3182812842. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Spanjersberg WR, Reurings J, Keus F, van Laarhoven CJ. Fast track surgery versus conventional recovery strategies for colorectal surgery. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2011;(2):CD007635. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD007635.pub2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Faiz O, Warusavitarne J, Bottle A, Tekkis PP, Darzi AW, Kennedy RH. Laparoscopically assisted vs. open elective colonic and rectal resection: a comparison of outcomes in English National Health Service Trusts between 1996 and 2006. Dis Colon Rectum. 2009;52:1695–1704. doi: 10.1007/DCR.0b013e3181b55254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Osler M, Iversen LH, Borglykke A, Mårtensson S, Daugbjerg S, Harling H, et al. Hospital variation in 30-day mortality after colorectal cancer surgery in Denmark: the contribution of hospital volume and patient characteristics. Ann Surg. 2011;253:733–738. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e318207556f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Almoudaris AM, Burns EM, Bottle A, Aylin P, Darzi A, Vincent C, et al. Single measures of performance do not reflect overall institutional quality in colorectal cancer surgery. Gut. 2013;62:423–429. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2011-301489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Finks JF, Osborne NH, Birkmeyer JD. Trends in hospital volume and operative mortality for high-risk surgery. N Engl J Med. 2011;364:2128–2137. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa1010705. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Coleman MP, Forman D, Bryant H, Butler J, Rachet B, Maringe C, et al. ICBP Module 1 Working Group. Cancer survival in Australia, Canada, Denmark, Norway, Sweden, and the UK, 1995–2007 (the International Cancer Benchmarking Partnership): an analysis of population-based cancer registry data. Lancet. 2011;377:127–138. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)62231-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Faiz O, Warusavitarne J, Bottle A, Tekkis PP, Clark SK, Darzi AW, et al. Nonelective excisional colorectal surgery in English National Health Service Trusts: a study of outcomes from Hospital Episode Statistics Data between 1996 and 2007. J Am Coll Surg. 2010;210:390–401. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2009.11.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ellis MC, Diggs BS, Vetto JT, Herzig DO. Trends in the surgical treatment of ulcerative colitis over time: increased mortality and centralization of care. World J Surg. 2011;35:671–676. doi: 10.1007/s00268-010-0910-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Damhuis RA, Wijnhoven BP, Plaisier PW, Kirkels WJ, Kranse R, van Lanschot JJ. Comparison of 30-day, 90-day and in-hospital postoperative mortality for eight different cancer types. Br J Surg. 2012;99:1149–1154. doi: 10.1002/bjs.8813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lilford R, Mohammed MA, Spiegelhalter D, Thomson R. Use and misuse of process and outcome data in managing performance of acute medical care: avoiding institutional stigma. Lancet. 2004;363:1147–1154. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(04)15901-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Pitches DW, Mohammed MA, Lilford RJ. What is the empirical evidence that hospitals with higher-risk adjusted mortality rates provide poorer quality care? A systematic review of the literature. BMC Health Serv Res. 2007;7:91. doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-7-91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Daley J, Forbes MG, Young GJ, Charns MP, Gibbs JO, Hur K, et al. Validating risk-adjusted surgical outcomes: site visit assessment of process and structure. J Am Coll Surg. 1997;185:341–351. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Main DS, Cavender TA, Nowels CT, Henderson WG, Fink AS, Khuri SF. Relationship of processes and structures of care in general surgery to postoperative outcomes: a qualitative analysis. J Am Coll Surg. 2007;204:1147–1156. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2007.03.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Main DS, Henderson WG, Pratte K, Cavender TA, Schifftner TL, Kinney A, et al. Relationship of processes and structures of care in general surgery to postoperative outcomes: a descriptive analysis. J Am Coll Surg. 2007;204:1157–1165. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2007.03.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Schifftner TL, Grunwald GK, Henderson WG, Main D, Khuri SF. Relationship of processes and structures of care in general surgery to postoperative outcomes: a hierarchical analysis. J Am Coll Surg. 2007;204:1166–1177. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2007.03.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Sweetland S, Green J, Liu B, Berrington de González A, Canonico M, Reeves G, et al. Million Women Study collaborators. Duration and magnitude of the postoperative risk of venous thromboembolism in middle aged women: prospective cohort study. BMJ. 2009;339:b4583. doi: 10.1136/bmj.b4583. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Wick EC, Shore AD, Hirose K, Ibrahim AM, Gearhart SL, Efron J, et al. Readmission rates and cost following colorectal surgery. Dis Colon Rectum. 2011;54:1475–1479. doi: 10.1097/DCR.0b013e31822ff8f0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Moore L, Turgeon AF, Émond M, Le Sage N, Lavoie A. Definition of mortality for trauma center performance evaluation: a comparative study. Crit Care Med. 2011;39:2246–2252. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e3182227a59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Garnick DW, DeLong ER, Luft HS. Measuring hospital mortality rates: are 30-day data enough? Ischemic Heart Disease Patient Outcomes Research Team. Health Serv Res. 1995;29:679–695. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Keogh B. Review into the Quality of Care and Treatment Provided by 14 Hospital Trusts in England: Overview Report; 2013. http://www.nhs.uk/NHSEngland/bruce-keogh-review/Documents/outcomes/keogh-review-final-report.pdf [accessed 29 July 2013]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.