Abstract

Glutathione (GSH), an intracellular tripeptide that combats oxidative stress, must be continually replaced due to loss through conjugation and destruction. Previous methods, estimating the synthesis of GSH in vivo, used constant infusions of labeled amino acid precursors. We developed a new method based on incorporation of 2H from orally supplied 2H2O into stable C-H bonds on the tripeptide. The incorporation of 2H2O into GSH was studied in rabbits over a two week period. The method estimated N, the maximum number of C-H bonds in GSH that equilibrate with 2H2O as amino acids. GSH was analyzed by liquid chromatography mass spectrometry after derivatization to yield GSH-N-ethylmaleimide (GSNEM). A model, which simulated the expected abundance at each mass isotopomer for the GSNEM ion at various values for N, was used to find the best fit to the data. The plateau labeling fit best a model with N= 6 of a possible 10 C-H bonds. Thus, the amino acids precursors do not completely equilibrate with 2H2O prior to GSH synthesis. Advantages of this new method include replacing costly amino acid infusions with the oral administration of 2H2O and a statistical basis for estimating N.

Keywords: glutathione, deuterated water, models, isotopomers, mass spectrometry, lc/ms

Introduction

Glutathione (GSH) is an endogenously synthesized tripeptide, glutamate-cysteine-glycine, which is critical for maintaining cellular redox balance and combating oxidative stress. GSH neutralizes free radicals in a in a cyclic pathway consuming NADPH and regenerating reduced GSH. Additionally, GSH forms conjugates with electrophilic compounds and detoxifies potential alkylating agents. Conjugation, plus the catabolic actions of the plasma enzyme, γ-glutamyl transpeptidase, depletes GSH. Thus, GSH must be constantly replenished by biosynthesis, which occurs largely in the liver. It is well established that GSH plasma and tissue levels decline in critical illness and this may be a major factor in multiple organ failure and cellular apoptosis (1). Thus, measuring the rate of synthesis of GSH is essential to understanding how cells and organisms respond to oxidative stress. We present a new method for estimating the synthesis of GSH using 2H2O as the tracer with analysis by liquid chromatography/mass spectrometry (LC/MS).

Estimating the rates of synthesis of GSH first reported by Waelsch and Rittenberg (2) who used 15N labeled glycine as a tracer and noted the rapid turnover of GSH relative to hepatic proteins. Early pioneering work by Meister and colleagues established that turnover in kidney exceeded that of liver (3) and that buthionine sulfoximine produced a decay in organ GSH levels as a result of inhibiting gamma-glutamylcysteine synthetase (4). Current methods for estimating GSH synthesis in vivo require the constant infusion of an isotopically labeled amino acid precursor (cysteine, glutamate or glycine). Stable isotopes are generally preferred over radio-isotopes for both animal and human studies. To estimate the rate of synthesis, the enrichment of the tracer amino acid in plasma is measured along with the enrichment of GSH in plasma, cells, or tissues over time (5). These data are used to estimate the rate of synthesis with the assumption that the plasma enrichment of the precursor amino acid is equivalent to the enrichment at the site of synthesis. However, it is difficult to independently confirm the validity of this assumption. In addition, the intravenous infusion of labeled amino acid is expensive and invasive. Finally, the infused stable isotope labeled amino acid may itself affect the rate of synthesis by increasing the concentration of a precursor in the biosynthetic pathway.

In contrast with previous work, the method described here does not involve intravenous infusions of labeled amino acids. Instead, a bolus intraperitoneal dose of 2H2O plus enriched drinking water is provided as a labeled precursor for estimating GSH biosynthesis. An advantage of using 2H2O as tracer is that the tracer does not increase the concentration of precursors in the biosynthetic pathway. Our method builds on the work of Previs (6), and Hellerstein (7) who utilized 2H2O to estimate protein synthesis and the work of Lee (8) who described general equations for these calculations. As with other 2H2O studies, our method assumes that 2H2O enrichment is identical throughout the body. It takes advantage of exchange reactions that incorporate 2H covalently into amino acids prior to the GSH biosynthesis. The relevant sites of incorporation are those covalent C-H bonds that freely exchange with water prior to GSH biosynthesis but do not exchange with water once the GSH biosynthesis is complete. Following Lee (8) we use the term, “Maximum incorporation number” (N) for this value. A key aspect of the method presented here was to determine the number of such sites. Determining the value of N facilitates measurements of GSH synthesis when the entire GSH pool does not turnover. It is also provides insight for estimating the extent of isotopic equilibrium of nonessential amino acids, which is required for the extension of this method for the FSR of larger peptides and proteins. To quantify GSH labeling we used the N-ethylmaleimide (NEM) derivative of GSH (GSNEM), which has 10 C-H bonds that may contribute to N (Figure 1). To estimate the actual value of N we used a novel method based on the statistics of the fit for models with different values of N to the observed isotopomer profile. We illustrate the use of this method estimating the synthesis of GSH in rabbit liver and blood cells.

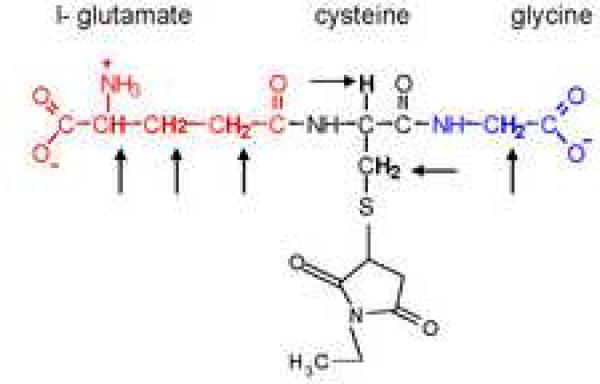

Figure 1.

Structure of glutathione-N-ethylmaleimide. The hydrogen atoms indicated by arrows are the 10 C-H bonds that may contribute to N.

Materials and Methods

Animal studies

The protocol was approved by the Subcommittee on Research Animal Care of the Massachusetts General Hospital. Animal studies were performed in compliance with guidelines of NIH and the institutional Center of Comparative Medicine. New Zealand rabbits weighing 3.0 - 3.25 Kg were purchased from Millbroke Farm Rabbits (Amherst, MA). The rabbits were housed with a 12-h light/dark cycle, ad libitum access to rabbit chow (PROLAB Rabbit formulas, Agaway Country Foods, Inc. Syracuse, NY) and regular water. Each animal underwent at least 3 days of acclimatization period to the environment. Short term studies were conducted in catheterized animals. Catheterization of jugular vein and carotid artery was conducted on the fourth day after overnight fast as previously described (9). On the third day following catheterization, animals received an intravenous bolus of deuterated saline (prepared with 0.9% NaCl and an equal volume of 2H2O under sterile conditions) targeted to reach 5% enrichment in the total body water (TBW) considering water as 75% of rabbit weight. Blood samples were withdrawn through the arterial catheter of a rabbit every hour from 2 to 12 hours. Long term studies were conducted on animals without catheterization. These animals also received an intraperitoneal dose of deuterated saline targeted to enrich TBW to 5% 2H2O and were offered 5% 2H2O as drinking water to maintain the TBW enrichment. Blood samples were withdrawn from the ear vein at 48, 144, 192, 240 and 336 hours. All blood samples were quickly centrifuged and plasma removed. The blood cells were hemolyzed in cold distilled water and stored at -80°C until analysis.

GSH derivatization and detection as GSNEM

Glutathione was derivatized as described by Steghens JP et al. (10). Briefly, 75 μl of the red cell hemolyzate or GSH standards (65-2000 μM in 0.5mM acetic acid) were mixed with 150 μl of solution A, consisting of NEM (40mM) and ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (EDTA, 2mM) in water:methanol, 85/15 (v/v) and 50 μl of solution B (sulphosalicylic acid (SSA), 2% (w/v)) and reacted at room temperature for one hour. The samples were centrifuged and 10 μl of 1M acetic acid was added to the supernatant prior to injection in the LC/MS (model 1100 LCMSD-SL, Agilent Technologies). The liquid chromatography was conducted with a Stability BS-C17 5um×150mm (Cluzeau labs, France), maintained at 45°C. A gradient was constructed using a mobile phase of 0.1% formic acid in water (v/v) and an organic phase of 0.1% formic acid in acetonitrile (v/v). The elution gradient began with 6 minutes at 100% mobile phase, followed by change over 1 minute to 100% organic phase where it remained for 2 additional minutes. The flow rate was 0.5 ml/min. Samples were maintained at 10°C in the autosampler, and 1μl was injected. Detection was carried out with a single quadrupole, in positive electron spray ionization mode at 350°C and 2.5kV with an entrance cone voltage at 15V. Mass spectra were recorded in selective ion monitoring mass to charge (m/z) 433 (M+H)+ for natural GSNEM, m/z 434 (M1), m/z 435 (M2), m/z 436 (M3) and integrated with the Chemstation software (Agilent, version Rev. B.03.01. [317]). All chemicals were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO); deuterated water was purchased from Cambridge Isotope Labs Inc., (Andover, MA).

Determination of plasma enrichment

Plasma water enrichment was measured following the method of Yang et al (11), with modifications as described by Previs et al. (6). Briefly, 10 μl of plasma were incubated overnight at room temperature with 2μl of 10N NaOH, 10μl distilled water, and 5μl 5% acetone in acetonitrile. The acetone was extracted with 500 μl chloroform and dried with sodium sulfate before GC/MS injection. Acetone was monitored at ions m/z 58 and m/z 59 (4).

Calculation and probability-based model

All isotopic data were converted to fractional abundance (FA) where the sum of the abundances of all detection masses was set to 1. The fractional abundance of observed isotopomers was used to estimate N for GSNEM. A model was constructed for N = 4 to 10 using simple probability equations for the chemical formula of the GSNEM ion analyzed. The equations below illustrate the calculations for the M0 isotopomer of GSNEM derivative of natural abundance M0(N=0). To calculate the probability of the M0 ion of the GSNEM we substitute the natural abundance of 12C, 14N, 1H, 16O and 32S into the chemical formula for the molecular ion.

| Eq. 1 |

Substituting the values for the constants yields:

| Eq. 2 |

This is the probability of a GSNEM M0 ion of natural abundance M0(N=0). Probabilities for M1, M2, and M3 ions are calculated based on this molecular formula and the probability of the enriched isotopes of each atom. To create a model for various values of N we include two classes of H atoms in the model. Hn represents those H sites that are labeled in accord with natural abundance deuterium while Hx represents the H sites that are labeled by exchange with 2H2O and contribute to N. If N = 10, the formula for the GSNEM ion is:

For these calculations the total number of H atoms (Hn + Hx) is maintained at 24, the number of H atoms in the molecular ion. Eq. 3 calculates the abundance of the M0 ion where 2H2O is 0.0469 and therefore the probability of 1Hx = 1- 0.0469 = 0.9531.

| Eq. 3 |

| Eq. 4 |

In developing these models we have been careful to include all isotopes even those, such as natural abundance 2H, which will be not be significant in the actual calculations. While the natural abundance of 2Hn is below detection, and 1Hn is essentially 1, the abundance of 1H in 2H2O = 0.9531 is significant, especially when raised to the 10th power as in this example. Including all ions provides a comprehensive modeling approach that can readily be adapted to other situations.

Results

Plasma water enrichment was nearly constant over time following the bolus injection and provision of drinking water enriched to 5% with 2H2O (Figure 2). The measured enrichments averaged 4.8%, slightly less than the target value of 5.0%. The difference is likely due to metabolic water. The time course of red blood cell GSH labeling was monitored by the fractional abundance of ions M0...M3 of GSNEM for 336 hours (2 weeks). Increase in the M1 ion of GSNEM illustrates the profile of labeling (Figure 3). These data are a composite of data from 14 different animals. The timecourse of M1 glutathione abundance was used to estimate the apparent fractional synthesis rate (FSR) by fitting data to the equation

| Eq. 5 |

Figure 2.

Water enrichment in rabbit plasma following an intraperitoneal bolus dose of 2H2O and 2H2O in drinking water targeted to result in 5% 2H2O enriched TBW. Mean ± SEM (smaller than symbols).

Figure 3.

Time course of GSH labeling in rabbit blood cells observed as M1 of GSNEM, (composite data for 14 animals). Error bars (SEM) were smaller than the symbols. Data are fit to equation for a filling a single pool in metabolic steady state (see Eq. 5).

Baseline abundance was estimated from samples taken prior to administering 2H2O. “Ap” in Eq. 5 is the difference between baseline (t = 0) and the plateau abundance estimated from the long term study at t > 200 hours. The observed FSR for rabbit blood cells was 0.018 per hour or 44% per day. The data for liver GSH enrichment of rabbits euthanized at different time points indicated that the GSH in liver reached an asymptotic value of 0.31 ± 0.04 and a synthesis rate of 272 % day−1, six times faster than the blood cells.

The labeling at the plateau was used to estimate N, the maximum number of incorporation sites, by comparison with the model values. Natural abundance GSNEM for M0 through M3, measured in blood cells from each animal prior to the exposure to 2H2O, was near the theoretical value M0(N=0) as calculated in Eqs 1- 2. The mean sum of square error was used as the criterion for the fit of models to data. Plateau enrichment data were compared to the model estimates as shown in Table 1, adjusted for each animal's plasma 2H2O level. The average sum of square error (n= 3) was plotted for each value of N (Figure 4). The best fit integer value for N was N=6 as indicated by the low error. N= 6 was the only integer value with an error equivalent to the fit of natural abundance GSH to the model with N=0, shown as the dashed line at the y axis. The calculations using integer values of N are based on the concept that specific C-H sites either exchange with 2H2O and contribute to N or do not exchange and thus do not contribute to N. However, even when an apparent plateau has been reached, non enriched amino acids, from diet or protein degradation, may continue to enter the amino acid metabolizing pathways leading to glutathione synthesis. Thus, the plateau value may represent a dynamic steady state with incomplete equilibration of amino acids C-H sites with 2H2O. To allow for this possibility, we included models where N is not an integer value. For example, the point plotted at 6.5 (Figure 4) represents a mixture of GSH ions, 50% N=6, 50% N=7. Our results indicate that the actual GSNEM labeling at plateau corresponds equally well to N= 6 or a mixture of N= 6 and N=7. We reject other models tested because the error for these models was significantly larger than for the fit to natural abundance. In summary, although the GSH molecule has 10 sites that potentially may become labeled in the presence of 2H2O (Figure 1), only approximately 6 six of these reach full equilibration in our animal model.

Table 1.

Expected fractional abundances of GSNEM isotopomers with varying values of N.

| Mass | N=0 | N=6 | N=7 | N=8 | N=9 | N=10 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M0 | 0.7702 | 0.5796 | 0.5528 | 0.5272 | 0.5028 | 0.4795 |

| M1 | 0.1553 | 0.2854 | 0.2991 | 0.3109 | 0.3209 | 0.3294 |

| M2 | 0.0624 | 0.1013 | 0.1099 | 0.1187 | 0.1276 | 0.1366 |

| M3 | 0.0102 | 0.0267 | 0.0302 | 0.0360 | 0.0378 | 0.0420 |

Figure 4.

Estimating N as the model with best fit to data. Theoretical models were constructed for M0 – M3 for each value of N = 4 to 9. The average error for the fit of plateau data to the models was plotted (red diamonds). The average error for N=0, natural abundance fit is plotted as dashed blue line at y axis. Non-integer values of N correspond to 50/50 mixtures as described in the Results.

Discussion

Previous studies of glutathione synthesis in vivo have infused labeled glycine (2;12;13); cysteine (14); or glutamate (15). Although most recent infusion studies employ stable isotopes, radiolabeled amino acids have also been used (3;16). These amino acid infusion protocols maintain labeled amino acids at constant plasma enrichment for only 6 to 12 hours. The rate of synthesis is estimated from the early time points during the quasi-linear portion of the exponential rise in labeling. In contrast, the 2H2O study was able to maintain constant 2H2O enrichment for two weeks and followed synthesis until a plateau was reached, corresponding to turnover of the entire GSH pool. Thus, an advantage of the less invasive 2H2O protocol is the ability to follow synthesis over long time periods. By following synthesis over two weeks we confirm that both blood cell and hepatic GSH synthesis fits well to a single compartment model in metabolic steady state (Figure 3). The labeling of blood cells is assumed to be due to cellular synthesis because erythrocytes and lymphocytes lack the ability to transport GSH (17). An additional advantage of the 2H2O method is that administration of 2H2O does not disturb amino acid pools, which may affect synthesis. Stable isotope infusions of labeled amino acids may affect pool size because the tracer must be detected above natural abundance of isotopes. This may be especially important for GSH because GSH synthesis is reported to be sensitive to the level of each amino acid (18). However, a limited comparison of the 2H2O results obtained here with studies of animal GSH synthesis indicates qualitatively similar results. For example, our results in rabbits agrees with previous studies in pigs reporting much more rapid GSH synthesis in liver than blood cells (12).

While the 2H2O method has advantages as cited above, an additional requirement for the 2H2O protocol is to estimate N. Our observation that N was less than the maximum value of 10 (Figure 1) and could be 6 or 6.5 may be relevant for other studies of peptide and protein synthesis using 2H2O. Previous work has found near, but not complete, equilibration of nonessential amino acids with body water at plateau enrichment (6;7). Our finding that N for GSH synthesis was significantly less than the maximum value illustrates the importance of determining N for each situation to obtain the best estimates of synthesis rates. Another issue with 2H2O is the extent of labeling of TBW. We targeted 5% 2H2O enrichment of TBW, which was well tolerated by rabbits. However, human use of 2H2O has been restricted to levels below 2.5% due to concerns about vertigo. Clearly, higher level of 2H2O enhanced the ability to determine N. From the signal to noise and reproducibility of our measurements, we estimate that GSH synthesis could be reliably estimated with our instrument with 2H2O at 1-2% TBW.

A number of methods have been proposed to estimate the value of N. The method of Lee (8) using the ratios of enrichment of M2/M1 and M3/M2 is especially noteworthy because it does not require labeling to the plateau value. However, it does require accurate corrections for natural abundance of carbon and other significant atoms. In our study this relationship did not yield stable values for N. Thus we relied on the plateau enrichment to estimate N. Our approach (Figure 4) employed a statistical method that compares observed isotopomer fractional abundances to computed models based on established values for isotope abundances. Our 2H2O approach does require computing the expected isotopomer profiles (Eqs 1- 4), but it does not require corrections for natural abundance, which can be complicated. In our approach the natural abundances of isotopomers are included in the model. In summary, we present a 2H2O based method for estimating GSH synthesis in vivo and provide a new method for assessing the value of N from plateau labeling data. This approach may serve as a model for estimating the synthesis of larger peptides and proteins with 2H2O.

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge helpful comments from H. Brunengraber and S.F. Previs and support from NIEHS RO1ES013925 and NIH P50 GM021700

Abbreviations used

- LC/MS

Liquid Chromatography/MS

- NEM

N-ethylmaleimide

- GSNEM

glutathione-N-ethylmaleimide

- TBW

total body water

- m/z

mass to charge ratio

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Reference List

- 1.Han D, Hanawa N, Saberi B, Kaplowitz N. Mechanisms of liver injury. III. Role of glutathione redox status in liver injury. Am.J.Physiol Gastrointest.Liver Physiol. 2006;291:G1–G7. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00001.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Waelsch H, Rittenberg D. The metabolism of glutathione. Science. 1939;90:423–424. doi: 10.1126/science.90.2340.423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sekura R, Meister A. Glutathione turnover in the kidney; considerations relating to the gamma-glutamyl cycle and the transport of amino acids. Proc.Natl.Acad.Sci.U.S.A. 1974;71:2969–2972. doi: 10.1073/pnas.71.8.2969. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Griffith OW, Meister A. Potent and specific inhibition of glutathione synthesis by buthionine sulfoximine (S-n-butyl homocysteine sulfoximine). J.Biol.Chem. 1979;254:7558–7560. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Reid M, Jahoor F. Methods for measuring glutathione concentration and rate of synthesis. Curr.Opin.Clin.Nutr.Metab Care. 2000;3:385–390. doi: 10.1097/00075197-200009000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Previs SF, Fatica R, Chandramouli V, Alexander JC, Brunengraber H, Landau BR. Quantifying rates of protein synthesis in humans by use of 2H2O: application to patients with end-stage renal disease. Am.J Physiol Endocrinol.Metab. 2004;286:E665–E672. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00271.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Busch R, Kim YK, Neese RA, Schade-Serin V, Collins M, Awada M, Gardner JL, Beysen C, Marino ME, Misell LM, Hellerstein MK. Measurement of protein turnover rates by heavy water labeling of nonessential amino acids. Biochim.Biophys.Acta. 2006;1760:730–744. doi: 10.1016/j.bbagen.2005.12.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lee WN, Bassilian S, Guo Z, Schoeller D, Edmond J, Bergner EA, Byerley LO. Measurement of fractional lipid synthesis using deuterated water (2H2O) and mass isotopomer analysis. Am.J.Physiol. 1994;266:E372–E383. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.1994.266.3.E372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hu RH, Yu YM, Costa D, Young VR, Ryan CM, Burke JF, Tompkins RG. A rabbit model for metabolic studies after burn injury. J.Surg.Res. 1998;75:153–160. doi: 10.1006/jsre.1998.5274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Steghens JP, Flourie F, Arab K, Collombel C. Fast liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry glutathione measurement in whole blood: micromolar GSSG is a sample preparation artifact. J.Chromatogr.B Analyt.Technol.Biomed.Life Sci. 2003;798:343–349. doi: 10.1016/j.jchromb.2003.10.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yang D, Diraison F, Beylot M, Brunengraber DZ, Samols MA, Anderson VE, Brunengraber H. Assay of low deuterium enrichment of water by isotopic exchange with [U-13C3]acetone and gas chromatography-mass spectrometry. Anal.Biochem. 1998;258:315–321. doi: 10.1006/abio.1998.2632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jahoor F, Wykes LJ, Reeds PJ, Henry JF, del Rosario MP, Frazer ME. Protein-deficient pigs cannot maintain reduced glutathione homeostasis when subjected to the stress of inflammation. J Nutr. 1995;125:1462–1472. doi: 10.1093/jn/125.6.1462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Reid M, Badaloo A, Forrester T, Morlese JF, Frazer M, Heird WC, Jahoor F. In vivo rates of erythrocyte glutathione synthesis in children with severe protein-energy malnutrition. Am.J Physiol Endocrinol.Metab. 2000;278:E405–E412. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.2000.278.3.E405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lyons J, Rauh-Pfeiffer A, Yu YM, Lu XM, Zurakowski D, Tompkins RG, Ajami AM, Young VR, Castillo L. Blood glutathione synthesis rates in healthy adults receiving a sulfur amino acid-free diet. Proc.Natl.Acad.Sci.U.S.A. 2000;97:5071–5076. doi: 10.1073/pnas.090083297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Humbert B, Nguyen P, Obled C, Bobin C, Vaslin A, Sweeten S, Darmaun D. Use of L-[(15)N] glutamic acid and homoglutathione to determine both glutathione synthesis and concentration by gas chromatography-mass spectrometry (GCMS). J Mass Spectrom. 2001;36:726–735. doi: 10.1002/jms.185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Douglas GW, Mortensen RA. The rate of metabolism of brain and liver glutathione in the rat studied with C14-glycine. J.Biol.Chem. 1956;222:581–585. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ookhtens M, Kaplowitz N. Role of the liver in interorgan homeostasis of glutathione and cyst(e)ine. Semin.Liver Dis. 1998;18:313–329. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-1007167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wu G, Fang YZ, Yang S, Lupton JR, Turner ND. Glutathione metabolism and its implications for health. J.Nutr. 2004;134:489–492. doi: 10.1093/jn/134.3.489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]