Abstract

1-Deoxy-d-xylulose 5-phosphate (DXP) synthase catalyzes formation of DXP from pyruvate and d-glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate (d-GAP) in a thiamin diphosphate (ThDP)-dependent manner, and is the first step in the essential pathway to isoprenoids in human pathogens. Understanding the mechanism of this unique enzyme is critical for developing new anti-infective agents that selectively target isoprenoid biosynthesis. The present study uses mutagenesis and a combination of protein fluorescence, circular dichroism and kinetics experiments to investigate the roles of Arg-420, Arg-478 and Tyr-392 in substrate binding and catalysis. The results support a random sequential, preferred order mechanism and predict Arg-420 and Arg-478 are involved in binding of the acceptor substrate, d-GAP. d-Glyceraldehyde, an alternative acceptor substrate lacking the phosphoryl group predicted to interact with Arg-420 and Arg-478, also accelerates decarboxylation of the pre-decarboxylation intermediate C2α-lactylthiamin diphosphate (LThDP) on DXP synthase, indicating this binding interaction is not absolutely required, and the hydroxyaldehyde sufficiently triggers decarboxylation. Unexpectedly, Tyr-392 contributes to d-GAP affinity and is not required for LThDP formation or its d-GAP-promoted decarboxylation. Time-resolved CD spectroscopy and NMR experiments indicate LThDP is significantly stabilized on R420A and Y392F variants compared to wild type DXP synthase in the absence of acceptor substrate, yet these substitutions do not appear to impact the rate of d-GAP-promoted LThDP decarboxylation in the presence of high d-GAP, and LThDP formation remains the rate-limiting step. These results suggest a role of these residues to promote d-GAP binding which in turn facilitates decarboxylation, and further highlight interesting differences between DXP synthase and other ThDP-dependent enzymes.

Keywords: DXP synthase, enzymology, thiamin, protein fluorescence, circular dichroism

INTRODUCTION

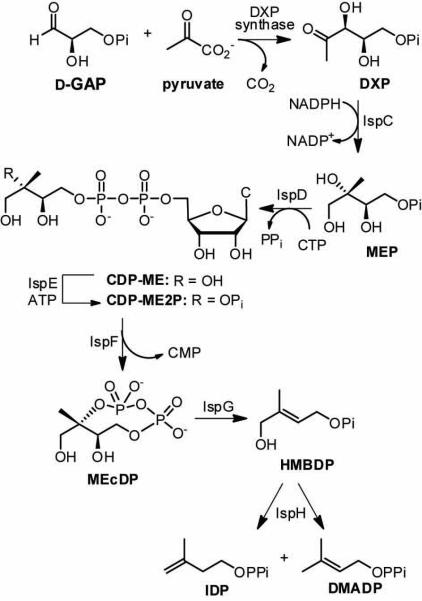

Isoprenoid biosynthesis is essential in all living systems. The isoprenoid natural products that play important roles in a variety of cellular functions across all species are structurally diverse, yet derive from the same 5-carbon building blocks, isopentenyl diphosphate (IDP) and dimethylallyl diphosphate (DMADP). Two distinct pathways to these important precursors exist. The methylerythritol phosphate (MEP) pathway (Figure 1) is widespread in human pathogens, including Mycobacterium tuberculosis and Plasmodium falciparum, but is absent in mammals, which utilize the orthogonal mevalonate (MVA) pathway as the sole source of IDP and DMADP. Consequently, the MEP pathway has emerged as a promising target for the development of anti-infective agents inhibiting non-mammalian isoprenoid biosynthesis.

Figure 1.

The MEP pathway for IDP and DMADP biosynthesis.

The MEP pathway initiates production of 1-deoxy-d-xylulose 5-phosphate (DXP) by the action of thiamin diphosphate (ThDP)-dependent DXP synthase. DXP is a branch point in bacterial metabolism [1,2], serving as a precursor in vitamin B1 and vitamin B6 biosynthesis [3,4], and is believed to serve a regulatory role to control flux through the MEP pathway [5]. The product of DXP synthase is generated by condensation of a donor substrate pyruvate and an acceptor substrate d-glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate (d-GAP) in a reaction that is reminiscent of carboligases (such as transketolase) and pyruvate decarboxylases (such as the E1 subunit of pyruvate dehydrogenase). Despite similarities in the chemical reactions catalyzed by DXP synthase and other ThDP-dependent enzymes, DXP synthase appears to be structurally and mechanistically unique in this enzyme class [6-10], and can therefore be considered a potential point of intervention in selective targeting of non-mammalian isoprenoid biosynthesis. Structural studies by Xiang et al. [6] suggest the two active sites are positioned between domains within each monomer of the catalytically active homodimer, in contrast to other ThDP-dependent enzymes known to position the active site at the dimer interface [6]. Mechanistically, DXP synthase appears to be unique; most notably, a requirement for ternary complex formation in DXP synthase catalysis has been proposed [7-10] further distinguishing this enzyme from all other ThDP-dependent enzymes believed to proceed via the classical ping-pong kinetic mechanism. Recent studies conducted by Patel et al. provide evidence for the remarkable stability of the C2α-lactylthiamin diphosphate (LThDP) intermediate on Escherichia coli DXP synthase in the absence of d-GAP [10]. The requirement for ternary complex formation in DXP synthase catalysis taken together with the observation that DXP synthase exhibits relaxed acceptor substrate specificity [11] has led to the design and synthesis of alkyl acetylphosphonates as unnatural bisubstrate analogs and selective inhibitors of DXP synthase [12].

The goal of the present study is to investigate factors important for substrate binding on DXP synthase, and to take steps to understand how impairment of substrate binding impacts LThDP formation and its subsequent decarboxylation on DXP synthase, which is uniquely triggered by the acceptor substrate. New evidence from protein fluorescence experiments supports a random sequential, preferred order mechanism in DXP synthase catalysis and reveals the roles of active site residues proposed to be critical for substrate binding. The results of protein fluorescence, CD and kinetic analyses demonstrate Arg-420 and Arg-478 as active site residues for binding of the acceptor substrate, d-GAP, but they are not essential for catalysis of LThDP formation. We note remarkable stabilizing effects of the R420A variant on LThDP in the absence of acceptor substrate, suggesting that Arg-420 could play a role to create a barrier to decarboxylation in the absence of d-GAP. Interestingly, these residues, which contribute significantly to binding of the substrate trigger for LThDP decarboxylation, are not absolutely required for the decarboxylation event. Stopped-flow CD results with d-glyceraldehyde suggest that the hydroxyaldehyde moiety on the acceptor substrate is sufficient to accelerate LThDP decarboxylation. We also report that R478A DXP synthase can indeed form DXP product, contrary to the previous report by Xiang et al. [6]. In addition, we have investigated the importance of Tyr-392, analogous to Tyr-599 of the PDHc E1 component which is known to interact via hydrogen bonding to a phosphono-LThDP mimic of the enzyme-bound LThDP intermediate [13]. Unexpectedly, Tyr-392 also appears to contribute to d-GAP affinity and is not required for catalysis of LThDP formation or decarboxylation. As with the R420A variant, the Y392F substitution appears to create a barrier to LThDP decarboxylation in the absence of d-GAP. The present study takes a first step to understand the roles of active site residues in this intriguing ThDP-dependent mechanism. Structural information on substrate-bound DXP synthase will guide future studies to identify factors governing the remarkable stability of LThDP on the enzyme, and its decarboxylation uniquely triggered by d-GAP.

RESULTS

Arg-478 is essential for d-GAP binding

Previous molecular docking analysis performed on Deinococcus radiodurans DXP synthase [9] suggested the phosphoryl group of d-GAP is anchored in the active site through interactions with two arginine residues, Arg-423 and Arg-480 (Figure 2), which correspond to Arg-420 and Arg-478 in E. coli DXP synthase. Xiang et al. [6] have speculated that Arg-478 may be important for d-GAP binding and catalysis. Thus, R478A E. coli DXP synthase was produced and kinetically characterized. The kinetic parameters for R478A DXP synthase were first determined using the enzyme-coupled assays previously reported [9,14]. R478A DXP synthase exhibits a 70-fold increase in the Kmd-GAP compared to wild type DXP synthase (Kmd-GAP = 1.6 ± 0.3 mM), while pyruvate affinity (Km) and turnover (kcat) of the substrates are relatively unaffected (Table 1, Figure 3). A comparably higher Kmd-GAP for the R478A variant is also measured by CD analysis (Kmd-GAP = 0.53 ± 0.10 mM, Figure 4) where DXP formation is monitored at 290 nm [10]. These data suggest Arg-478 is involved in d-GAP binding and recognition, but is not crucial for catalysis, as previously hypothesized [6].

Figure 2.

Active site residues of interest highlighted on D. radiodurans DXP synthase [6]. R480, R423 and Y395 correspond to R478, R420 and Y392, respectively, on E. coli DXP synthase.

Table 1.

Summary of wild-type and variant DXP synthase used in this study.

| Enzyme |

Kmd-GAP (μM) |

Kdd-GAP (μM) |

Kmpyruvate (μM) |

Kd

pyruvate (μM) |

kcat (min−1) |

kcat/Km

d-GAP (μM−1min−1) |

kcat/Km

pyruvate (μM−1min−1) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| WT | 23.5 ± 1.7a | 2000 ± 500b |

49 ± 8a | 230 ± 70 b | 154 ± 7a | 6.8 ± 0.4a | 3.2 ± 0.4a |

| R478A | 1600 ± 300 | n.d. c | 54 ± 7 | 80 ± 30d | 200 ± 10 | 0.14 ± 0.02 | 3.1 ± 0.5 |

| R420A | n.d. c | n.d. c | n.d. c | 37 ± 8d | n.d. c | 0.0018 ± 0.0003e | n.d. c |

| Y392F | 210 ± 20 | n.d. | 73 ± 4 | 230 ± 60b | 179 ± 4 | 0.91 ± 0.06 | 2.37 ± 0.15 |

Brammer, et al. [9].

Kd determined using total protein fluorescence.

Saturation not achieved under assay conditions.

Kd determined using CD.

Specificity constant estimated from the linear portion of the Michaelis-Menten curve.

Figure 3.

Km determinations for R478A (a-b), R420A (c), and Y392F (d-e) DXP synthase variants using the IspC coupled assay.

Figure 4.

Determination of Km D-GAP on R478A, R420A and Y392F using CD.

The role of Arg-478 in d-GAP binding was further investigated using protein fluorescence. Our previous study describing tryptophan fluorescence experiments to study substrate binding [9] indicated comparable micromolar Kd values for both pyruvate and d-GAP. Subsequent experiments suggest there is significant contribution by tryptophan-based probe instability to fluorescence changes upon addition of either substrate to the enzyme probe, which leads to underestimation of Kd in each case. Thus, experimental conditions were re-optimized to detect total intrinsic protein fluorescence changes for wild-type E. coli DXP synthase and variants upon the introduction of substrates. Under optimized conditions (Methods) quenching of wild-type protein fluorescence is observed upon addition of either pyruvate or d-GAP. An apparent Kdpyruvate of 230 ± 70 μM (Figure 5d) is comparable to the apparent Kdpyruvate measured by CD analysis [10] and ~4-fold higher than previously reported [9]. The apparent Kdd-GAP of 2.0 ± 0.5 mM (Figure 5f) measured under these conditions is ~30-fold higher than previously reported [9]. The lower apparent Km for each substrate (Table 1) compared to the corresponding Kd value measured here is consistent with the accumulation of intermediate enzyme forms along the reaction coordinate, subsequent to ternary complex formation [15], and points to the possibility of conformational changes of the ternary complex prior to catalysis. The lower Kd measured for pyruvate compared to Kdd-GAP suggests the E-pyruvate complex is more readily formed in the random sequential mechanism. As expected, quenching of fluorescence was not observed upon titration of d-GAP to R478A DXP synthase up to concentrations of 15 mM (Figure 5h), also consistent with the significant effect of this substitution on the apparent Kmd-GAP. These results support the role of Arg-478 in d-GAP binding, suggesting that d-GAP binding to free enzyme measured by monitoring changes in protein fluorescence is directed to the active site and is unlikely to be a consequence of non-specific binding of the aldehyde group of d-GAP.

Figure 5.

Substrate binding analysis of DXP synthase by intrinsic protein fluorescence. Minimal change in fluorescence is observed upon titration of DXP synthase with water (a and b). Titration of DXP synthase with pyruvate (c and d) or D-GAP (e and f) results in measurable fluorescence quenching. D-GAP titration of R478A (g and h) and R420A (i and j) results in negligible changes in fluorescence.

The critical role of d-GAP to promote decarboxylation on DXP synthase [10] raises questions about contributions of d-GAP-binding residues in this event. Thus, the individual steps of LThDP formation and decarboxylation were investigated on R478A DXP synthase using stopped-flow CD under pre-steady state conditions at 6 °C, using enzyme in excess of pyruvate (single turnover conditions). LThDP forms on R478A DXP synthase upon titration with pyruvate (positive CD band centered at 315 nm, Figure 6a). The formation of LThDP is biphasic (Figure 6b), described by two consecutive rate constants (k1 = 0.85 ± 0.03 s−1 and k1′ = 0.29 ± 0.02 s−1, Table 2). LThDP formation is followed by slow decarboxylation in the absence of d-GAP (k2 = 0.04 ± 0.004 s−1) on R478A DXP synthase (Table 2, Figure 6b). LThDP formation and decarboxylation, determined by measuring the accumulation and disappearance of LThDP at 313 nm, are within two-fold of the rates observed on wild type DXP synthase [10]. In an experiment to measure d-GAP promoted decarboxylation of LThDP, LThDP was preformed in one syringe by mixing R478A DXP synthase and pyruvate at 6 °C, and was then rapidly mixed with d-GAP (2 mM) placed in the second syringe. Although product formation is likely occurring during this time, as determined by gCHSQC NMR spectroscopy (Figure 7), there is negligible contribution of the DXP signal (288 nm) at 313 nm (< 0.1 mdeg), and the rate of LThDP depletion can be confidently determined. The rate of d-GAP promoted LThDP decarboxylation on R478A DXP synthase is comparable to wild type (Table 2, Figure 6c). Overall, the results indicate that while Arg-478 is important for d-GAP binding, the enzyme can still achieve a comparable rate of d-GAP-promoted LThDP decarboxylation in its absence, at high d-GAP concentration.

Figure 6.

a) Formation of 1′, 4′–iminopyrimidyl-LThDP (315 nm) from pyruvate (10-500 μM) by R478A DXP synthase (29.6 0M) at 5 °C; b) Pre-steady state analysis of LThDP formation and decarboxylation under single turnover conditions on R478A (30 0M) with pyruvate (15 0M), in the absence of D-GAP at 6 °C. Data were fit to equation 2 (see text); c) Pre-steady state analysis of LThDP decarboxylation (k2) and resynthesis (k1) on R478A (24 0M was pre-mixed with 150 μM pyruvate to form LThDP) in the presence of 1 mM D-GAP at 6 °C (inset) fitting the expansion of early behavior to equation 4.

Table 2.

Microscopic rate constants for LThDP formation and decarboxylation and DXP formation on R478A, R420A and Y392F at 6 °C.

| Enzymes | Formation of LThDP (s−1) | LThDP Decarboxylation (s−1) | Formation of DXP(s−1) |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| − d-GAPb | + d-GAPc | − d-GAPd | + d-GAPe | ||

| WT a |

k1 = 1.39 ± 0.05 (k1’ = 0.16 ± 0.02) |

k1 = 0.68 ± 0.01 | k2 = 0.07 ± 0.006 | k2 = 42.0 ± 1.0 |

k4 = 1.24 − 0.03 (k4′ = 0.29 ± 0.01) |

| R478A |

k1 = 0.85 ± 0.03 (k1′ = 0.29 ± 0.02) |

k1 = 0.84 ± 0.004 | k2 = 0.04 ± 0.004 | k2 = 36.5 ± 1.1 |

k4 = 0.78 ± 0.08 (k4′ = 0.26 ± 0.02) |

| R420A |

k1 = 1.24 ± 0.01 (k1′ = 0.28 ±0.002) |

k1 = 0.67 ± 0.003 | No decomposition |

k2 = 38.8 ± 0.9 | k4 = 0.71 ± 0.02 |

| Y392F |

k1 = 1.06 ± 0.03 (k1′ = 0.3 ± 0.01) |

k1 = 0.82 ± 0.01 | k2 = 0.01 ± 0.003 | k2 = 39.5 ± 1.4 |

k4 = 1.34 ± 0.12 (k4′ = 0.34 ± 0.01) |

Analysis reported in Patel et al. [10].

Formation of LThDP is biphasic, described by k1 and k1′. Rate constants for R478A and Y382F were obtained using equation 2. Rate constants for R420A were obtained using equation 3.

Accumulation of the signal at 313 nm (attributed to re-synthesis of LThDP) following d-GAP-promoted decarboxylation of pre-formed LThDP. k1 is obtained by fitting the data to a single exponential function.

Rate of LThDP decarboxylation observed following buildup of LThDP in the absence of d-GAP. For R478A and Y382F, k2 is obtained from equation 2.

Rate of d-GAP-promoted decarboxylation where k2 is obtained from equation 4.

Figure 7.

NMR detection of [1-13C]-DXP formation by R478A DXP synthase during pre-steady state, D-GAP promoted decarboxylation of pre-formed [C2β-13C]-LThDP. a) Only LThDP is present on R478A DXP synthase 5 seconds after addition of D-GAP, as determined by examination of the C6′-H region in the 1H NMR spectrum; b) Detection of 13CH3 labeled groups: [1-13C]-DXP (28.5 %), [C2β-13C]-LThDP (35.5 %) and [3-13C]-pyruvate (23.3 %) by 1D gCHSQC spectroscopy (decoupled) 5 seconds after the addition of D-GAP to pre-formed [C2β-13C]-LThDP.

The R420A substitution reduces affinity for d-GAP

Molecular docking analysis [9] and crystallography studies [6] have suggested Arg-420 as a possible anchoring point for the phosphoryl group of d-GAP. Thus, R420A DXP synthase was produced and kinetically characterized. A near 4,000-fold decrease in kcat/Kmd-GAP, as determined from the linear region of the Michaelis-Menten curve in the enzyme coupled assay (Table 1, Figure 3), is measured for this variant. In this case, saturation by d-GAP could not be achieved without inhibiting the coupling enzyme, IspC. CD analysis to monitor DXP formation confirms saturation by d-GAP is not achieved at low millimolar concentrations (Figure 4). Further, quenching of fluorescence was not observed upon titration of d-GAP to R420A DXP synthase up to concentrations of 15 mM (Figure 5j), supporting a role of R420 in d-GAP binding and suggesting d-GAP binding measured by protein fluorescence is directed to the active site.

The R420A substitution stabilizes LThDP in the absence of d-GAP but does not reduce the rate of d-GAP promoted decarboxylation

The biphasic accumulation of LThDP formation on R420A (k1 = 1.24 ± 0.01 s−1, k1′ = 0.28 ± 0.002 s−1), determined by monitoring LThDP formation at 313 nm as described above (Figure 8a-b), is also comparable to wild type DXP synthase (Table 2), suggesting Arg-420 is not critical for LThDP formation. However, decarboxylation of LThDP in the absence of d-GAP on this variant is not measurable over 50 s, demonstrating a remarkable stabilizing effect of R420A on LThDP compared to wild type DXP synthase (Figure 8b). The rate of d-GAP promoted decarboxylation of LThDP on R420A DXP synthase was measured as described above for the R478A variant (k2 = 38.8 ± 0.9 s−1) and is comparable to wild type DXP synthase (Table 2, Figure 8c), indicating it is not essential for catalysis in d-GAP promoted decarboxylation of LThDP. The observation that R420A DXP synthase catalyzes the rate limiting step at a comparable rate to wild type DXP synthase under pre-steady state conditions suggests the near 4000-fold decrease in turnover efficiency (Table 1) measured for this variant under steady-state conditions is likely caused by a substantial increase in Kmd-GAP.

Figure 8.

a) Formation of 1′, 4′–iminopyrimidyl-LThDP (318 nm) from pyruvate (10-200 μM) by R420A DXP synthase (29.6 μM) at 5 °C; b) Pre-steady state analysis of LThDP formation and decarboxylation under single turnover conditions on R420A (30 μM) with pyruvate (15 μM), in the absence of D-GAP at 6 °C. Data were fitted to equation 3 (see text); c) Pre-steady state analysis of LThDP decarboxylation (k2) and resynthesis (k1) on R420A (30 μM was pre-mixed with 150 μM pyruvate to form LThDP) in the presence of 1 mM D-GAP at 6 °C (inset) fitting the expansion of early behavior to equation 4.

Tyr-392 contributes to d-GAP affinity

The observation that Kdpyruvate > Kmpyruvate suggests the E-LThDP complex exhibits lower affinity compared to the E-LThDP-GAP ternary complex and prompted an investigation of residues that might be involved in binding pyruvate and stabilization of ThDP-bound intermediates along the reaction coordinate. The crystal structure of the Escherichia coli PDHc E1 component in complex with C2α-phosphono-LThDP indicates Tyr-599 stabilizes this stable pre-decarboxylation intermediate analogue via hydrogen bonding with one of the phosphonyl oxygen atoms [13]. On the basis of this observation, it was reasoned that Tyr-599 plays a similar role to stabilize the carbonyl oxygen of LThDP and position this intermediate for decarboxylation. Sequence homology predicts Tyr-599 in PDHc E1 to be analogous to Tyr-392 in E. coli DXP synthase. Xiang et al. hypothesized on the basis of structure that Tyr-392 may interact with d-GAP [6] but reported a Y392F variant to exhibit turnover efficiency similar to wild type DXP synthase. We hypothesized that, in a manner similar to Tyr-599 of PDHc E1, Tyr-392 may move into position to stabilize LThDP either upon binding of pyruvate in a manner that does not promote decarboxylation, or upon binding of d-GAP to facilitate decarboxylation. To investigate the role of Tyr-392 in DXP synthase substrate binding and catalysis, Y392F DXP synthase was constructed and kinetically characterized (Table 1) using the enzyme coupled assay previously reported [9,14]. Y392F DXP synthase exhibits a pronounced, near eight-fold decrease in kcat/Kmd-GAP, apparently driven by a change in affinity for d-GAP (Kmd-GAP = 210 ± 20 μM, Figure 3) which is supported by steady-state kinetic analysis using CD (Kmd-GAP = 280 ± 30 μM, Figure 4); substrate turnover (kcat) by Y392F is comparable to wild type (Table 1). Contrary to our expectations, a mere 1.5-fold increase in Kmpyruvate is observed for Y392F suggesting the hydroxyl group of Tyr-392 may contribute to, but is not essential for, binding of pyruvate or ThDP-bound intermediates along the reaction coordinate.

Interestingly, preliminary experiments to determine an apparent Kdpyruvate by measuring changes in fluorescence of Y392F at 6 °C indicated pyruvate binds to Y392F DXP synthase (Kd = 230 ± 60 μM, Figure 9a,b) and wild type DXP synthase (Kd = 230 ± 70 μM, Figure 5c) with comparable affinity, further suggesting that Tyr-392 is not critical for formation and stabilization of the LThDP intermediate known to form upon binding of pyruvate to wild type DXP synthase [10]. Thus, a detailed investigation of the formation of LThDP on Y392F was carried out using CD analysis as previously reported [10]. Consistent with fluorescence binding experiments carried out on Y392F DXP synthase, CD analysis at 5 °C confirms the formation of 1′,4′-iminopyrimidinylLThDP, characterized by the appearance of a CD signal at 313 nm (Figure 9c), upon titration of Y392F DXP synthase with pyruvate. An apparent Kdpyruvate on Y392F of 113 μM (Figure 9d) is again comparable to that measured on wild type DXP synthase (89.4 μM) using CD spectroscopy [10].

Figure 9.

a-b) Pyruvate binding analysis by intrinsic protein fluorescence of Y392F DXP synthase; c) Formation of 1′, 4′–iminopyrimidyl-LThDP (313 nm) at 5 °C from pyruvate (30-500 .M) by Y392F DXP synthase (29.9 .M) at 5 °C and the corresponding binding curve (d); e) Pre-steady state analysis of LThDP formation and decarboxylation under single turnover conditions on Y392F (35 .M) with pyruvate (17.5 .M), in the absence of D-GAP at 6 °C. Data were fit to equation 2 (see text); f) Pre-steady state analysis of LThDP decarboxylation (k2) and (k1) re-synthesis on Y392F (27 .M was pre-mixed with 205 .M pyruvate to form LThDP) in the presence of 100 .M D-GAP at 6 °C (inset) fitting the expansion of early behavior to equation 4.

Y392F stabilizes LThDP in the absence of d-GAP but does not affect d-GAP promoted decarboxylation

To determine the rates of formation and subsequent decarboxylation of LThDP (313 nm) on Y392F in the absence of d-GAP, stopped-flow CD experiments were performed under pre-steady state conditions at 6 °C, using Y392F DXP synthase in excess of pyruvate as described above. The formation of LThDP is again biphasic (k1 = 1.06 ± 0.03 s−1, k1′ = 0.3 ± 0.01 s−1, Figure 9e) and comparable to wild type DXP synthase. However, LThDP appears to undergo decarboxylation in the absence of d-GAP at a lower rate (k2 = 0.01 ± 0.003 s−1) compared to wild type, indicating this substitution stabilizes LThDP on DXP synthase. Further evidence for LThDP stability on Y392F was obtained by NMR analysis [16] of a mixture of Y392F DXP synthase and pyruvate, which was incubated on ice for 50 s and then quenched with TCA. The proton NMR spectrum shows only the presence of LThDP with a C6′-proton chemical shift of 7.26 ppm [10], confirming its stability on Y392F (data not shown).

The rate constant for d-GAP-dependent decarboxylation of LThDP on Y392F was measured using stopped-flow CD spectroscopy. In this experiment, LThDP was pre-formed in one syringe by mixing Y392F and pyruvate at 6 °C, and this solution was then rapidly mixed with d-GAP placed in the second syringe. The rate constant for decarboxylation of LThDP on Y392F (k2 = 39.5 ± 1.4 s−1, Figure 9f) was measured by monitoring depletion of the CD band at 313 nm. A similar experiment carried out using 500 μM d-GAP in the second syringe afforded the same rate of LThDP decarboxylation, confirming saturation with d-GAP.

Kinetic constants for product formation by R420A, R478A and Y392F DXP synthase

Time-resolved CD spectroscopy was used to determine the rates for the formation of DXP at 297 nm [10] from pyruvate and d-GAP on R420A, R478A and Y392F (Table 2, Figure 10). In each case, the DXP synthase variant (1.04 μM active centers) in one syringe was mixed with pyruvate and d-GAP placed in the second syringe at 6 °C. Similar to wild type DXP synthase, formation of DXP is biphasic on R478A (k4 = 0.78 ± 0.08 s−1 and k4′ = 0.26 ± 0.02 s−1) and Y392F DXP synthase (k4 = 1.34 ± 0.12 s−1 and k4′ = 0.34 ± 0.01 s−1). Interestingly, formation of DXP on R420A DXP synthase is monophasic (k4 = 0.71 ± 0.02 s−1). Despite significant increases in Kmd-GAP for these variants, the rates of DXP formation are within two-fold of wild type DXP synthase in each case (Table 2).

Figure 10.

Pre-steady state DXP formation from pyruvate and D-GAP by DXP synthase variants at 6 °C a) R478A; b) R420A; c) Y392F.

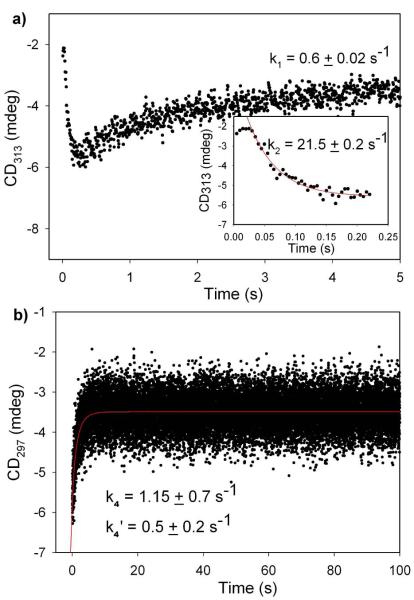

Alternate substrate d-glyceraldehyde promotes LThDP decarboxylation on wild type DXP synthase but does not affect overall rate of DX product formation

It was reported previously that d-glyceraldehyde can act as a co-substrate for the DXP synthase-catalyzed reaction; kcat is nearly the same as with the true substrate d-GAP but Kmd-glyceraldehydeis higher than Kmd-GAP [7,11]. We carried out stopped-flow CD experiments similar to those performed with d-GAP, to monitor LThDP decarboxylation. LThDP was pre-formed by mixing wild type DXP synthase with pyruvate in one syringe then reacting with d-glyceraldehyde in the second syringe, and CD changes were monitored at 313 nm. The rate of LThDP decarboxylation promoted with d-glyceraldehyde is k2 = 21.5 ± 0.2 s−1 (Figure 12a), ~2-fold lower than the rate of d-GAP promoted decarboxylation of LThDP (Table 2). However, the overall rate of DX product formation (condensation product of pyruvate and d-glyceraldehyde) (k4 = 1.15 ± 0.7 s−1; k4′ = 0.5 ± 0.2 s−1, Figure 12 b) remains similar to the rate of DXP product formation on wild type DXP synthase [10].

Figure 12.

a) Pre-steady state analysis of LThDP decarboxylation (k2) and re-synthesis (k1) on wild type DXP synthase (47.5 %M of enzyme was pre-mixed with 500 %M pyruvate to form LThDP) in the presence of 30 mM D-glyceraldehyde at 8 °C (inset) fitting the expansion of the early behavior to equation 4. b) Pre-steady state DX product formation from pyruvate and D-glyceraldehyde by wild type DXP synthase at 8 °C. Data were fitted to equation 5.

DISCUSSION

Toward identification of active center residues essential for binding and catalysis, we have constructed and kinetically characterized R420A, R478A and Y392F variants of DXP synthase from E. coli. Substitutions of Arg-420 and Arg-478 were expected to impact d-GAP affinity, on the basis of molecular docking analysis [9] and structural studies [6]. Indeed, each of these substitutions causes a significant lowering of the specificity constant, kcat/Kmd-GAP. Protein fluorescence experiments suggest these Arg-to-Ala substitutions decrease the weak binding affinity of d-GAP to DXP synthase, as evidenced by a lack of observable change in fluorescence upon titration of either variant with d-GAP. While Xiang et al. have suggested Arg-478 is crucial for catalysis [6], our results indicate a comparable kcat to wild type for this variant. It is possible the lack of activity on R478A observed by Xiang et al. can be attributed to the use of d-GAP at a concentration well below the Kmd-GAP for this variant. Stopped-flow CD experiments performed under pre-steady state conditions indicate the rate of LThDP formation (rate limiting step) [10] on both variants is comparable to wild type DXP synthase, supporting the notion that Arg-420 and Arg-478 are not critical for catalysis during LThDP formation. The results suggest the significant lowering of kcat/Kmd-GAP on R478A and R420A variants is driven by a decrease in d-GAP affinity on both. The two roles for d-GAP in DXP synthase-catalyzed DXP formation, including the acceleration of LThDP decarboxylation (E-LThDP-GAP) and acceptor in the carboligation step (E-enamine-GAP), implies two distinct Km values, one for each role, and the apparent Km measured in steady state experiments is a composite. Interestingly, despite the substantial increase in apparent Kmd-GAP, the rate of d-GAP promoted decarboxylation of LThDP on R478A and R420A variants is also comparable with wild type DXP synthase, supporting the idea that the first role of d-GAP can be satisfactorily fulfilled on these variants, and the very high Km could reflect a significant contribution from the affinity of d-GAP in the later carboligation step (represented by E-enamine-GAP). A lack of observable d-GAP binding to free enzyme in each case suggests the mechanism of these variants is ordered sequential, in which pyruvate binds first resulting in LThDP formation, and LThDP decarboxylation is facilitated at high d-GAP.

We anticipated Tyr-392 on DXP synthase might play a similar role to Tyr-599 on PDHc E1 [13], and predicted that a Y392F DXP synthase variant would exhibit a significant increase in Kmpyruvate and a substantial retardation in the rate of d-GAP promoted decarboxylation. Contrary to our expectations, steady state parameters (kcat and Kmpyruvate) and Kdpyruvate are not impacted by removal of the hydroxyl group of Tyr-392, nor are the rates of LThDP formation and d-GAP-promoted decarboxylation. These results argue that Tyr-392 is not critical to position the carboxyl group for decarboxylation through a direct hydrogen bonding interaction. Rather, Tyr-392 appears to contribute to the apparent Kmd-GAP.

An interesting observation is the remarkable stability of LThDP on R420A and to a lesser extent on Y392F, indicated by significantly reduced rates of LThDP decarboxylation on these variants in the absence of d-GAP. This work and previously reported studies indicate DXP synthase requires a ternary complex [7-10]. We have demonstrated LThDP readily forms on DXP synthase upon addition of pyruvate, and is slow to undergo decarboxylation in the absence of acceptor substrate d-GAP [10]. The data presented here suggest Arg-420 and Tyr-392 may play a role to create a barrier to LThDP decarboxylation in the absence of d-GAP, a barrier that is even larger on R420A and Y392F, as evidenced by the requirement of a ternary complex and remarkable stability of LThDP on R420A and Y392F DXP synthase variants. The presence of d-GAP in the ternary complex could function in re-positioning these residues to effectively lower this barrier to achieve the intrinsic decarboxylation rate constant of ~40 s−1 under conditions of saturating d-GAP. Hence, the slower decarboxylation rate (compared to the wild type DXP synthase) exhibited by the variants in the absence of d-GAP is compensated for by addition of d-GAP, such that the rate-limiting step remains LThDP formation. Interestingly, DXP synthase proteins are identified primarily by the presence of a signature DRAG sequence motif [17]. The importance of the DXP synthase DRAG sequence (residues 419-422) has not been investigated. Arg-420 is located within the DRAG sequence, and the data presented here suggests Arg-420 of the DRAG motif is important in d-GAP binding and recognition. Other well-characterized ThDP-dependent enzymes lack the DRAG signature sequence and catalyze ping-pong bi bi kinetic mechanisms. Perhaps the presence of the DRAG motif, and particularly Arg-420, permits recognition of the acceptor substrate d-GAP in the rapid equilibrium random sequential mechanism.

In the present study we have identified residues that stabilize LThDP and play a role in acceptor substrate binding. Interestingly, while all variants created display decreased affinity for the substrate, d-GAP, the LThDP decarboxylation rate still is not rate limiting overall. Regarding the substrate requirement for accelerating LThDP decarboxylation, the stopped-flow CD results performed with d-glyceraldehyde as acceptor substrate are informative. In the presence of d-glyceraldehyde, a rate of 21 s−1 can be achieved for LThDP decarboxylation, even in the absence of the phosphoryl group. This result suggests the phosphoryl group in d-GAP might not be directly involved in promoting LThDP decarboxylation, and leaves the hydroxyaldehyde moiety as the likely source of the observations.

Our results suggest Arg-420, Arg-478 and Tyr-392 contribute to d-GAP affinity in its second role as acceptor during carboligation, and the factors governing LThDP stability on DXP synthase and the trigger for its decarboxylation remain elusive. Possible explanations for the retardation of LThDP decarboxylation in the absence of d-GAP include an inability to attain the optimal dihedral angle for decarboxylation of the C2α-lactyl group (i.e., no adherence to the Dunathan hypothesis [18] unless d-GAP is present). Several studies support the notion of an optimal dihedral angle for decarboxylation. In the X-ray structure of C2α-lactylthiamin [19] the C2α-C2β bond (leading to the carboxylate) is indeed perpendicular to the thiazolium ring. A notable difference of this structure compared to structures of enzyme-bound ThDP is the S conformation with respect to the disposition of the 4′-aminopyrimidine and thiazolium rings around the bridging methylene group, rather than the V conformation universally observed for enzyme-bound ThDP. Tittmann et al. have observed LThDP on pyruvate oxidase by cryocrystallography [20] in which this bond is “out of the aromatic ring plane by a few degrees, indicating strain that might help to drive the decarboxylation reaction”. The structure of the stable LThDP analogue, phosphonolactylThDP on the E1 component of the E. coli pyruvate dehydrogenase complex in the V conformation shows a near perpendicular C2α-Pβ bond [13]. An additional study on Zymomonas mobilis pyruvate decarboxylase [21] may also provide insight to the long-lived LThDP intermediate on DXP synthase. In this case, LThDP accumulates on Glu437Asp PDC, and the scissile C2α-C(carboxylate) bond deviates significantly from the perpendicular orientation required for efficient decarboxylation. As suggested above, it is possible that LThDP on DXP synthase is maintained in a similar low (or un-) reactive state, and binding of d-GAP induces a re-orientation to attain optimal dihedral angle for decarboxylation. Structures of DXP synthase (and variants with long-lived LThDP) with pyruvate and/or d-GAP will offer further mechanistic insight, and could guide saturation mutagenesis experiments to identify the residues involved in the d-GAP promoted decarboxylation of LThDP.

In our previous CD analysis of d-GAP-promoted decarboxylation of LThDP [10], we reported that re-synthesis of LThDP in the presence of excess pyruvate could account for the subsequent increase in the signal at 313 nm upon LThDP decarboxylation and depletion of d-GAP. Similarly, apparent LThDP re-synthesis following a rapid LThDP decarboxylation phase is observed here with all three variants (Figures 6c, 8c, and 9f). Despite having d-GAP in excess for R478A and R420A, the signal at 313 nm is shown to increase, albeit at a slower rate than LThDP formation in the absence of d-GAP (Table 2). Further, LThDP is observed by proton NMR after 30 s (Arg-variants) or 5 s (Y392F variant) in the presence of pyruvate and excess d-GAP (data not shown), suggesting LThDP can accumulate even in the presence of d-GAP, which is known to promote decarboxylation at a higher rate than LThDP formation.

In addition to the novel kinetic and binding information presented, there are some important issues raised by the results that will be explored in detail in future studies. (1) A closer inspection of the behavior of the signal at 313 nm on wild type DXP synthase and all three variants reveals two distinct “pauses”, time periods during which the signal at 313 nm does not change. The first pause (20-30 ms) occurs immediately upon addition of d-GAP, prior to the rapid decrease in signal at 313 nm, and a second, longer pause occurs for a period of ~200 ms immediately following LThDP depletion and prior to apparent LThDP re-synthesis (Figures 6c, 8c, and 9f, inset). The cause of this peculiar behavior is unknown and raises questions about the conformational dynamics, including the possibility of hysteretic behavior, and alternating reactivity of active sites on DXP synthase, both of which have been reported on some ThDP-dependent enzymes [22-27]. It is conceivable that the first pause occurring upon addition of d-GAP could signify a change in conformation of the ternary complex prior to decarboxylation (the first role of d-GAP), and this would be consistent with the observation that Kd > Km. (2) Similarly, the need for two consecutive exponentials to fit the rate of LThDP formation at 313 nm and product formation at 297 nm in stopped-flow CD experiments could reflect alternating active sites. However, these remain open questions, as conformational dynamics and active site communication are not yet defined on DXP synthase (and are not portrayed in Figure 11). Understanding these three issues will not only provide a deeper understanding of the enzyme, but also aid in the design of specific inhibitors.

Figure 11.

Catalytic cycle of DXP synthase with microscopic rate constants referred to in Table 2. The rate constants presented in Table 2 were obtained by assuming irreversible forward rate constants.

The unusual stability of LThDP in the absence of d-GAP makes DXP synthase unique among ThDP enzymes. Understanding the fundamental differences in DXP synthase catalysis (Figure 11) compared to other ThDP-dependent enzymes will provide the basis for selective inhibitor design toward the long-term goal to develop new anti-infective agents targeting early stage isoprenoid biosynthesis. Crystallographic structures of DXP synthase and these variants could also be useful to gain a deeper understanding of the LThDP stabilization mechanism and the factors driving LThDP decarboxylation.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

General

Spectrophotometric analyses were performed on a Beckman DU 800 UV-Visible spectrophotometer. Primers were purchased from IDT DNA. Protein fluorescence studies were performed on a Horiba Jobin Yvon FluoroMax-3 spectrofluorimeter equipped with a Wavelength Electronics 5 Amp-40 Watt temperature controller. CD spectra were recorded on an Applied Photophysics Chirascan CD spectrometer (Leatherhead, U.K.) in 2.4 mL volume with 1 cm path length cell. Kinetic traces were recorded on a Pi*-180 stopped-flow CD spectrometer (Applied Photophysics, U.K.) with a 10 mm path length. For stopped-flow experiments, LThDP was detected at 313 nm, and DXP was detected at 297 nm.

Generation of R420A, R478A, and Y392F DXP synthase variants

Using site directed mutagenesis, R478A, R420A, and Y392F E. coli DXP synthase variants were constructed using the following protocol. Plasmid dxs-pET37b (wild-type DXP synthase), which encodes for a C-His8 tagged protein [11], was purified from E. coli TOP-10 competent cells. Mutagenesis reactions were carried out as previously reported [9] using dxs-pET37b as a template and the following primers: R420A, 5′-CCGGTCCTGTTCGCCATCGACGCCGCGGGCATTGTTGGTGCTGAC-3′; 5′-GTCAGCACCAACAATGCCCGC-GGCGTCGATGGCGAACAGGACCGG-3′. R478A, 5′-GTCAGCGGTGCGCTACCCGGCGGGC-3′; 5′-CACGCCGACCGCGTTGCCCGCCGGG-3′. Y392F, 5′-CAAACCCATTGTCGCGATTT-TCTCCACTTTCCTGCAACGC-3′; 5′-GCGTTGCAGGAAAGTGGAGAA AATCGCGACAATGG-GTTTG-3′. The constructs were fully sequenced to confirm the presence of desired mutation. Constructs were then transformed into E. coli BL21 (DE3) competent cells, and R420A, R478A, and Y392F DXP synthase variants were overproduced and purified as described previously [9]. R420A DXP synthase was isolated with a yield of 10.4 mg/L; R478A DXP synthase was isolated with a yield of 14.3 mg/L; Y392F DXP synthase was isolated with a yield of 11.6 mg/L.

Protein fluorescence of wild type and variant DXP synthase enzymes

All solutions contained HEPES (100 mM, pH 8.0), 2 mM MgCl2, 100 mM NaCl, 2.5 mM TCEP, and 5 μM either wild type or variant enzymes (final volume of 150 μL). Unless otherwise noted, all samples were excited at 280 nm (0.4 nm bandpass), and emission spectra were collected from 300 to 380 nm (10 nm bandpass) at 25 °C every 2.5 nm with an integration time of 0.1 sec. For the titration of wild-type DXP synthase with pyruvate, emission spectra were collected at 6 °C to eliminate error associated with pyruvate turnover All spectra were normalized by taking the sample emission spectra and dividing it by the reference emission spectra (S/R), and were additionally corrected by subtracting emission spectra acquired on samples containing no protein. Dilutions resulting from addition of ligand were accounted for in the final emission spectra. Experiments were performed in triplicate. Fluorescence data were normalized by taking the ratio of the area under the curve to starting enzyme only samples using KaleidaGraph from Synergy Software (version 4.0). Solutions were stirred with a pulled and sealed glass pipet.

Kinetic characterization of DXP synthase variants

All variants were characterized using IspC as a coupling enzyme as reported previously [9]. The concentration of d-GAP in stock solutions containing d,l-GAP was determined as previously reported [28,29]. Briefly, DXP synthase reaction mixtures containing HEPES (100 mM, pH 8.0), 1 mg/mL BSA, 2 mM MgCl2, 2.5 TCEP, 1 mM ThDP, 100 μM NADPH, 1 μM IspC, d,l-GAP, and pyruvate were pre-incubated at 37 °C for 5 min. Wild-type DXP synthase (100 nM), Y392F DXP synthase (200 nM), R420A DXP synthase (1 μM), or R478A DXP synthase (100 nM) was added to initiate each reaction, and the rate of NADPH depletion in the coupled step was monitored spectrophotometrically at 340 nm at 37 °C. The rate of NADPH depletion was used to calculate initial rates of DXP formation. Kinetic analyses were performed using GraFit version 7 from Erithacus Software. In the case of R420A DXP synthase, the second order rate constant kcat/Km was calculated from the slope of the linear region of the Michaelis-Menten curve.

CD titration of R420A with pyruvate

R420A DXP synthase (29.6 μM active centers) was titrated with pyruvate (10 - 200 μM) in 100 mM HEPES (pH 8.0) containing 100 mM NaCl, 0.1 mM ThDP and 1 mM MgCl2 at 5 °C. An apparent Kdpyruvate of 37 ± 8 μM (nH = 1.2 ± 0.3) was calculated by fitting the data to equation 1.

CD titration of R478A with pyruvate

R478A DXP synthase (29.6 μM active centers) was titrated with pyruvate (10 - 500 μM) in the same buffer described for R420A at 5 °C. After apparent saturation with 0.5 mM pyruvate, (500 μM) d-GAP was added. An apparent Kdpyruvate of 80 ± 30 μM (nH = 1.0 ± 0.2) was calculated by fitting the data to equation 1.

CD titration of Y392F with pyruvate

Y392F DXP synthase (29.9 μM active centers) was titrated with pyruvate (30-500 μM) in 100 mM HEPES (pH 8.0) containing 100 mM NaCl, 0.2 mM ThDP and 1 mM MgCl2 at 5 °C. After apparent saturation with 500 μM pyruvate, (50-200 μM) d-GAP was added. The apparent Kdpyruvate was calculated by fitting the data to equation 1.

| (1) |

where CDλ is the observed CD signal at a particular wavelength, CDmaxλ the maximum CD signal at saturation with ligand, [Ligand] is the concentration of substrate, and nH is the Hill coefficient.

Pre-steady state analysis of LThDP formation and decarboxylation on R420A, R478A and Y392F DXP synthase in the absence of d-GAP

In all pre-steady state analyses to observe formation and decarboxylation of LThDP, the LThDP intermediate was detected by CD at 313 nm. To measure the rate of LThDP formation, a solution containing enzyme in one syringe was mixed with an equal volume of a solution containing pyruvate in the second syringe, both in buffer A containing 50 mM Tris (pH 8.0), 100 mM NaCl, 0.5 mM ThDP, 2.0 mM MgCl2, 1 mM DTT, 1% glycerol at 6 °C. For R420A and R478A DXP synthase, 60 μM active centers and 30 μM pyruvate was used, and for Y392F DXP synthase 70 μM active centers and 35 μM pyruvate was used. In each case, the reaction was monitored at the CDλ corresponding to LThDP (313 nm). Data from seven repetitive shots were averaged and fit to the appropriate equation. For R478A and Y392F DXP synthase, there is a biphasic accumulation of LThDP followed by a slow decarboxylation phase, and data were fit to a triple exponential model (equation 2)

| (2) |

where the rate constants k1 and k1’ represent the faster and slower phase, respectively, of LThDP formation, k2 represents the rate of LThDP decarboxylation (in the absence of d-GAP), and c is CDmaxλ in the exponential rise to maximum. For R420A DXP synthase, there is a similar biphasic accumulation of LThDP, which does not undergo decarboxylation, and data were fit to a double exponential model (equation 3).

| (3) |

Pre-steady state analysis of LThDP decarboxylation on R420A, R478A and Y392F DXP synthase in the presence of d-GAP

A solution containing enzyme was pre-mixed with pyruvate at 6 °C in buffer A to form LThDP in one syringe, and this solution was then rapidly mixed with an equal volume of a solution containing d-GAP in the same buffer in the second syringe at 6 °C. For R420A DXP synthase (59.3 μM active centers), 300 μM pyruvate and 2 mM d-GAP was used. For R478A DXP synthase (47.5 μM active centers), 300 μM pyruvate, and 2 mM d-GAP was used. For Y392F (54.8 μM active centers), 411 μM pyruvate and 200 μM d-GAP (or 500 μM d-GAP) was used. In each case, the reaction was monitored at 313 nm to observe depletion of LThDP, and the data were fit to a single exponential decay model (equation 4) where k2 represents the rate of LThDP decarboxylation (in the presence of d-GAP) and c is CDminλ in the exponential decay model.

| (4) |

The increase in the signal at 313 nm following decarboxylation in all cases was fit to a single exponential function where k1 represents the rate of LThDP re-synthesis in the presence of d-GAP. In all cases, data from seven repetitive shots were averaged and fit to the appropriate equation.

To estimate the contribution of the unused stereoisomer of d,l-GAP to the CD signal at 313, we measured the CD signal of d-glyceraldehyde, which formed a negative CD signal at 290 nm (molar ellipticity was presumed to be comparable to that of d-GAP, (data not shown) The signal (0.035 mdeg/mM d-glyceraldehyde at 313 nm) is negligible compared to that of LThDP at the same wavelength. To estimate the contribution of accumulating DXP to the signal at 313 nm, pyruvate (2 mM) and d-GAP (2 mM) were mixed with Y392F (1 mg/mL), and the reaction was allowed to proceed to completion. The CD spectrum was acquired, showing a negligible difference of 0.1 mdeg between the reaction mixture containing DXP and the Y392F baseline (data not shown).

Pre-steady state formation of DXP

The R478A, R420A or Y392F DXP synthase variant (1.04 μM active centers) in buffer A placed in one syringe was mixed with an equal volume of 2 mM pyruvate (1 mM for R420A) and 2 mM d-GAP (1 mM for R420A) in the same buffer placed in the second syringe. Spectra were recorded for 100 s at 6 °C. For R478A and Y392F DXP synthase, data were fit to a double-exponential model (equation 5) where the rate constants k4 and k4′ represent the faster and slower phase, respectively, of DXP formation, and c is CDmaxλ in the exponential rise to maximum. For R420A, the data were fit to a single exponential model where k4 represents the rate of DXP formation.

| (5) |

To estimate contribution of the unused stereoisomer of D,L-GAP to the CD signal at 297 nm, we measured the CD signal of d-glyceraldehyde as described above. The signal (0.09 mdeg/mM d-glyceraldehyde at 297 nm) is negligible compared to DXP at the same wavelength.

Pre-steady state LThDP decarboxylation on wild type DXP synthase in the presence of d-glyceraldehyde

LThDP decarboxylation and re-synthesis at 313 nm were observed by mixing wild type DXP synthase (47.5 μM active centers) with pyruvate (500 μM) in one syringe to pre-form LThDP, and then mixing with 30 mM d-glyceraldehyde placed in the second syringe, both in buffer A. The reaction was monitored for 5 s at 8 °C. The high concentration of d-glyceraldehyde was selected based upon the high Kmd-glyceraldehyde, with wild type DXP synthase [7].

DX product formation from pyruvate and d-glyceraldehyde by wt DXP synthase

DX product formation was observed at 297 nm by mixing 1 μM wild type DXP synthase in one syringe with 30 mM d-glyceraldehyde and 5 mM pyruvate in the second syringe both in buffer A. The reaction was monitored for 100 s at 8 °C.

Detection of ThDP-bound intermediate by 1H NMR spectroscopy

NMR spectra were acquired on a Varian 500 MHz instrument. The water signal was suppressed by pre-saturation. A total of 16384 scans was collected with a recycle delay of 2.0 s. The reaction mixture containing Y392F (28 mg/mL, 415 μM active centers) in 20 mM Tris (pH 8.0), 100 mM NaCl, 0.2 mM ThDP and 1 mM MgCl2 (buffer prepared in D2O to reduce the intensity of buffer peak in the region 7 – 8 ppm) was mixed with 1 mM pyruvate in the same buffer to form LThDP. The reaction was incubated on ice for 50 s and quenched with 12.5% TCA in 1 M DCl/D2O. The mixture was centrifuged at 15,700 g for 20 min, and the 1H NMR spectrum of the supernatant was recorded.

Similar reaction conditions were used to observe LThDP intermediates by NMR on the R478A, R420A and Y392F DXP synthase variants in the presence of d-GAP. To form LThDP, enzyme (250-300 μM) was incubated with 500 μM pyruvate on ice for 30 seconds. The reaction mixture was then further incubated on ice for an additional 30 sec with 2 mM d-GAP (R478A and R420A) or 5 seconds with 500 μM d-GAP (Y392F), then quenched with acid.

Detection of [1-13C]-DXP by gradient 13C-Heteronuclear Single Quantum Coherence NMR spectroscopy

NMR spectra were acquired on a Varian 600 MHz instrument. A reaction mixture containing R478A (18 mg/mL) in 20 mM KH2PO4 (pH 7.5), 100 mM NaCl, 150 μM ThDP, 0.5 mM MgCl2 was mixed with 500 μM 3-13C pyruvate and incubated on ice for 30 sec to pre-form [C2β-13C]-LThDP (200 μl reaction volume). The reaction mixture was then incubated on ice with 2 mM d-GAP for 5 sec and then quenched with 12.5% TCA in 1 M DCl/D2O. The mixture was centrifuged at 15,700 g for 20 min, and the 1H-NMR spectrum of the supernatant was recorded. The water signal was suppressed by pre-saturation. A total of 4096 scans was collected with a recycle delay of 2.0 s. The data indicate that only LThDP is bound to the enzyme (Figure 7a). This same mixture was subjected to 1D gradient 13C-Heteronuclear Single Quantum Coherence (gCHSQC) NMR analysis to determine the extent of [1-13C]-DXP product formation during this time period. The 13CH3 region was integrated (Figure 7b) to determine the extent of [1-13C]-DXP formation. The coupled spectra (not shown) indicate JCH = 127 Hz for each of the species present.

Rates of DXP formation catalyzed by R420A, R478A and Y392F DXP synthase monitored by CD spectroscopy

The assays were carried out by direct detection of DXP formation at 290 nm at 37 °C (Figure 4). The assay mixtures (2.4 mL) contained 100 mM HEPES (pH 8.0), 100 mM NaCl, 0.1 mM ThDP, 2 mM MgCl2, 1 mM DTT, varying d-GAP and pyruvate. The reactions were initiated by addition of enzyme (20 μg). The rate of DXP formation was calculated from the slope of Δmdeg vs time plot. The Km value for d-GAP was calculated by fitting the data to a Hill function (equation 1). For R420A, d-GAP (0.25 – 2 mM) and 1 mM pyruvate were used. Saturation was not achieved up to 2 mM d-GAP. For R478A, d-GAP (0.15 – 2 mM) and 1 mM pyruvate were used (Kmd-GAP = 0.53 ± 0.10 mM, nH = 1.1 ± 0.1). For Y392F, d-GAP (0.025 – 1.25 mM) and 1 mM pyruvate were used (Kmd-GAP = 280 ± 30 μM, nH = 1.2 ± 0.1).

Analysis of the time course of LThDP formation and depletion by both steady state and time-resolved CD measurements at 313 nm. This assignment takes advantage of the multiple observations from Rutgers, providing evidence that all ThDP-bound covalent intermediates with tetrahedral substitution at the C2α position exist in their 1′,4′-iminopyrimidyl (IP) tautomeric form (rather than in the conventional 4′-aminopyrimidine, or AP tautomeric form) at pH values near and above the pKa of the 4′-aminopyrimidinium (APH+) conjugate acid form. Hence, the positive CD band at 313 nm reports the IP tautomeric form of LThDP. The chemical nature of the species corresponding to the CD signal was confirmed by NMR spectra for several conditions. In this paper there are potential interfering CD signals that needed to be ruled out. a) Since we are using racemic GAP, unreacted L-GAP enantiomer, expected to have a signal near 290 nm, does not contribute to the signal at 313 nm, as mentioned under Experimental Procedures. b) The product DXP, expected to have a signal near 285 nm, which forms within 5 s, does not contribute to the signal at 313 nm; as also mentioned under Experimental Procedures. c) The contribution from the AP tautomer in DXP in buffer at most is −1 mdeg/30 micromolar enzyme at this pH; while the AP form is visible in wild type DXP, very weak or none is observed on the three variants presented. Thus, the contribution of the AP form at 313 nm to stopped flow is zero.

Acknowledgement

The authors are grateful to Dr. Natalia Nemeria for helpful discussions of the CD experiments and Katie Heflin for help with enzyme preparations. This work was supported in part by National Institute of Health Grants GM084998 (to L.A.B.B and C.F.M.) and GM050380 (F.J.)

Abbreviations

- IDP

isopentenyl diphosphate

- DMADP

dimethylallyl diphosphate

- MEP

methylerythritol phosphate

- DXP

1-deoxy-d-xylulose 5-phosphate

- DX

1-deoxy-d-xylulose

- ThDP

thiamin diphosphate

- LThDP

C2α-lactylthiamin diphosphate

- d-GAP

d-glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate

- TK

transketolase

- PDHc E1

the E1 component of the Escherichia coli pyruvate dehydrogenase complex

- CD

circular dichroism

- TCEP

tris(2-carboxyethyl)phosphine

- TCA

trichloroacetic acid

- gCHSQC

gradient 13C Heteronuclear Single Quantum Coherence

Footnotes

Author Contributions: C.L.F.M and F.J. designed this project. L.A.B.B cloned, overproduced, and purified all proteins, and performed protein fluorescence and steady state kinetic experiments and analyzed these results. H.P. performed all circular dichroism experiments and NMR experiments and analyzed these results. L.K. performed and analyzed gCHSQC NMR experiments. C.L.F.M., F.J., L.A.B.B., and H.P. wrote this manuscript.

REFERENCES

- 1.Sprenger GA, Schörken U, Wiegert T, Grolle S, de Graaf AA, Taylor SV, Begley TP, Bringer-Meyer S, Sahm H. Identification of a thiamin-dependent synthase in Escherichia coli required for the formation of the 1-deoxy-d-xylulose 5-phosphate precursor to isoprenoids, thiamin, and pyridoxol. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 1997;94:12857–12862. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.24.12857. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lois LM, Campos N, Putra SR, Danielsen K, Rohmer M, Boronat A. Cloning and characterization of a gene from Escherichia coli encoding a transketolase-like enzyme that catalyzes the synthesis of d-1-deoxyxylulose 5-phosphate, a common precursor for isoprenoid, thiamin, and pyridoxol biosynthesis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 1998;95:2105–2110. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.5.2105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Himmeldirk K, Kennedy IA, Hill RE, Sayer BG, Spenser ID. Biosynthesis of vitamins B1 and B6 in Escherichia coli: Concurrent incorporation of 1-deoxy-d-xylulose into thiamin (B1) and pyridoxol (B6) Chem. Comm. 1996;271:1187–1188. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.48.30426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hill RE, Himmeldirk K, Kennedy IA, Pauloski RM, Sayer BG, Wolf E, Spenser ID. The biogenetic anatomy of vitamin B6. A 13C NMR investigation of the biosynthesis of pyridoxol in Escherichia coli. J. Biol. Chem. 1996;271:30426–30435. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.48.30426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Brown AC, Eberl M, Crick DC, Jomaa H, Parish T. The nonmevalonate pathway of isoprenoid biosynthesis in Mycobacterium tuberculosis is essential and transcriptionally regulated by Dxs. J. Bacteriol. 2010;192:2424–2433. doi: 10.1128/JB.01402-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Xiang S, Usunow G, Lange G, Busch M, Tong L. Crystal structure of 1-deoxy-d-xylulose 5-phosphate synthase, a crucial enzyme for isoprenoids biosynthesis. J. Biol. Chem. 2007;282:2676–2682. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M610235200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Eubanks LM, Poulter CD. Rhodobacter capsulatus 1-deoxy-d-xylulose 5-phosphate synthase: Steady-state kinetics and substrate binding. Biochemistry. 2003;42:1140–1149. doi: 10.1021/bi0205303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sisquella X, de Pourcq K, Alguacil J, Robles J, Sanz F, Anselmetti D, Imperial S, Fernàndez-Busquets X. A single-molecule force spectroscopy nanosensor for the identification of new antibiotics and antimalarials. FASEB J. 2010;24:4203–4217. doi: 10.1096/fj.10-155507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Brammer LA, Smith JM, Wade H, Freel Meyers CL. 1-Deoxy-d-xylulose 5-phosphate synthase catalyzes a novel random sequential mechanism. J. Biol. Chem. 2011;286:36522–36531. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.259747. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Patel H, Nemeria NS, Brammer LA, Freel Meyers CL, Jordan F. Observation of thiamin- bound intermediates and microscopic rate contants for their interconversion on 1-deoxy-d-xylulose 5-phosphate synthase: Dramatic rate acceleration of pyruvate decarboxylation by d-glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2012;134:18374–18379. doi: 10.1021/ja307315u. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Brammer LA, Freel Meyers CL. Revealing Substrate Promiscuity of 1-deoxy-d-xylulose 5-Phosphate Synthase. Org. Lett. 2009;11:4748–4751. doi: 10.1021/ol901961q. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Vierling R, Smith JM, Freel Meyers CL. Selective inhibition of E. coil 1-deoxy-d-xylulose 5-phosphate synthase by acetylphosphonates. Med. Chem. Comm. 2012;3:65–67. doi: 10.1039/C1MD00233C. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Arjunan P, Sax M, Brunskill A, Chandrasekhar K, Nemeria N, Zhang S, Jordan F, Furey W. A thiamin-bound, pre-decarboxylation reaction intermediate analogue in the pyruvate dehydrogenase E1 subunit induces large scale disorder-to-order transformations in the enzyme and reveals novel structural features in the covalently bound adduct. J. Biol. Chem. 2006;281:15296–15303. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M600656200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Altincicek B, Hintz M, Sanderbrand S, Wiesner J, Beck E, Jomaa H. Tools for discovery of inhibitors of the 1-deoxy-d-xylulose 5-phosphate (DXP) synthase and DXP reductoisomerase: An approach with enzymes from the pathogenic bacterium Pseudomonas aeruginosa. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 2000;190:329–333. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.2000.tb09307.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fersht A. Structure and mechanism in protein science: A guide to enzyme catalysis and protein folding. W.H. Freeman; New York: 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tittmann K, Golbik R, Uhlemann K, Khailova L, Schneider G, Patel M, Jordan F, Chipman DM, Duggleby RG, Hubner G. NMR Analysis of covalent intermediates in thiamin diphosphate enzymes. Biochemistry. 2003;42:7885–7891. doi: 10.1021/bi034465o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hahn FM, Eubanks LM, Testa CA, Blagg BSJ, Baker JA, Poulter CD. 1-Deoxy-d-xylulose 5-phosphate synthase, the gene product of open reading frame (ORF) 2816 and ORF 2895 in Rhodobacter capsulatus. J. Bacteriol. 2001;183:1–11. doi: 10.1128/JB.183.1.1-11.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dunathan HC. Conformation and reaction specificity in pyridoxal phosphate enzymes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 1966;55:712–716. doi: 10.1073/pnas.55.4.712. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Turano A, Furey W, Pletcher J, Sax M, Pike D, Kluger R. Synthesis and crystal structure of an analog of 2-(α-lactyl)thiamin, racemic methyl 2-hydroxy-2-(2-thiamin)ethylphosphonate chloride trihydrate. A conformation for a least-motion, maximum-overlap mechanism for thiamin catalysis. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1982;104:3089–3095. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wille G, Meyer D, Steinmetz A, Hinze E, Golbik R, Tittmann K. The catalytic cycle of a thiamin diphosphate enzyme examined by cryocrystallography. Nat. Chem. Biol. 2006;2:324–328. doi: 10.1038/nchembio788. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Meyer D, Neumann P, Parthier C, Friedemann R, Nemeria N, Jordan F, Tittmann K. Double duty for a conserved glutamate in pyruvate decarboxylase: Evidence of the participation in stereoelectronically controlled decarboxylation and in protonation of the nascent carbanion/enamine intermediate. Biochemistry. 2010;49:8197–8212. doi: 10.1021/bi100828r. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sergienko EA, Wang J, Polovnikova L, Hasson MS, McLeish MJ, Kenyon GL, Jordan F. Spectroscopic detection of transient thiamin diphosphate-bound intermediates on benzoylformate decarboxylase. Biochemistry. 2000;39:13862–13869. doi: 10.1021/bi001214w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sergienko EA, Jordan F. New model for activation of yeast pyruvate decarboxylase by substrate consistent with the alternating sites mechanism: Demonstration of the existence of two active forms of the enzyme. Biochemistry. 2002;41:3952–3967. doi: 10.1021/bi011860a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Booth CK, Nixon PF. Reconstitution of holotransketolase is by a thiamin-diphosphate-magnesium complex. Eur. J. Biochem. 1993;218:261–265. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1993.tb18373.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tate JR, Nixon PF. Measurement of Michaelis constant for human erythrocyte transketolase and thiamin diphosphate. Anal. Biochem. 1987;160:78–87. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(87)90616-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Nemeria NS, Arjunan P, Chandrasekhar K, Mossad M, Tittmann K, Furey W, Jordan F. Communication between thiamin cofactors in the Escherichia coli pyruvate dehydrogenase complex E1 component active centers. J. Biol. Chem. 2010;285:11197–11209. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.069179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kale S, Arjunan P, Furey W, Jordan F. Conformational ensemble modulates cooperativity in the rate-determining catalytic Step in the E1 component of the Escherichia coli pyruvate dehydrogenase multienzyme complex. J. Biol. Chem. 2007;282:28106–28116. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.065508. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Krebs EG. Glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase from yeast : GAP + DPN + P ⇄ 1,3-Diphosphoglycerate + DPNH + H+ Methods Enzymol. 1955;1:407–411. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Amelunxen RE, Carr DO. Glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase from rabbit muscle. Methods Enzymol. 1975;41:264–267. doi: 10.1016/s0076-6879(75)41060-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]