Abstract

This article emphasizes the basis for origin and importance of tumor patterns in diagnosis of oral and maxillofacial tumors. In this article, histological patterns and subpatterns of head and neck tumors are enlisted. Although, undifferentiated tumors remain a challenge to the histopathologist, by describing the histological patterns and the subpatterns of the tumors, an attempt has been made for the diagnosis of the tumors and subsequently for implementation of precise treatment plan for the same.

Keywords: Head and neck tumors, histological patterns, tumor histology

INTRODUCTION

Histological patterns and/or subpatterns are characteristic of particular tumors or group of tumors; hence for the histopathological diagnosis, these particular patterns are important. The knowledge of various patterns and subpatterns in different tumors helps in the diagnosis and delivery of appropriate treatment. The basis for different tumor patterns is thought to be the epithelial mesenchymal cell interaction as well as the interaction of various cytoskeletal organelles of these cells. Epithelial mesenchymal transition (EMT) has been postulated as a versatile mechanism that facilitates cellular repositioning and redeployment during embryonic development, tissue reconstruction after injury, carcinogenesis and tumor metastasis.[1,2] It is theoretically assumed that the disturbed function of tumor tissues is the result of EMT and the hypothesis originates from parallels drawn between the morphology and behavior of locomotory and sedentary cells in vitro and in various normal and pathologic processes in vivo. Wnt signaling through an activated complex of the lymphoid-enhancing factor-1 (LEF-1), transcription factor and the cell adhesion molecule, β-catenin and more recently transforming growth factor-β (TGF-β) have implicated a significant role in causing EMT in both development, pathology and tumor metastasis. But there is neither a convincing evidence for conversion of epithelial cells into mesenchymal cell lineages in vivo nor the optical and electron microscopy support the postulated involvement of EMT in induced and naturally occurring tumors.[1,2] The origin and basis for the different patterns still remain a subject of research.[3]

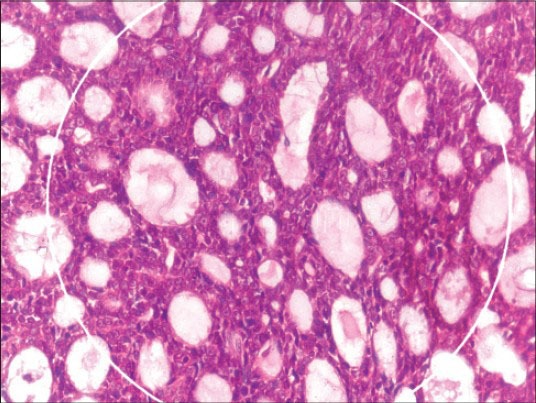

In the present article, an attempt has been made to classify the histological patterns that are encountered in head and neck tumors [Table 1].

Table 1.

Histological patterns with examples

MAIN HISTOLOGICAL PATTERNS ENCOUNTERED IN HEAD AND NECK TUMORS

Glandular/pseudoglandular

Nonglandular epithelial/epithelioid pattern

Round cell pattern

Spindle cell pattern

Biphasic pattern

Surface epithelial patterns associated with or affected by neoplastic process.

These main patterns are further subdivided into different subpatterns as follows:

A. Glandular/pseudoglandular [Table 1]

This category includes various tumors and tumor-like conditions composed of tumor cells that are epithelial or epithelioid, which form distinct glandular or pseudoglandular structures.[4] The term glandular is used to describe structures that resemble normal glands or ducts.

Following subpatterns are commonly recognized in this group.

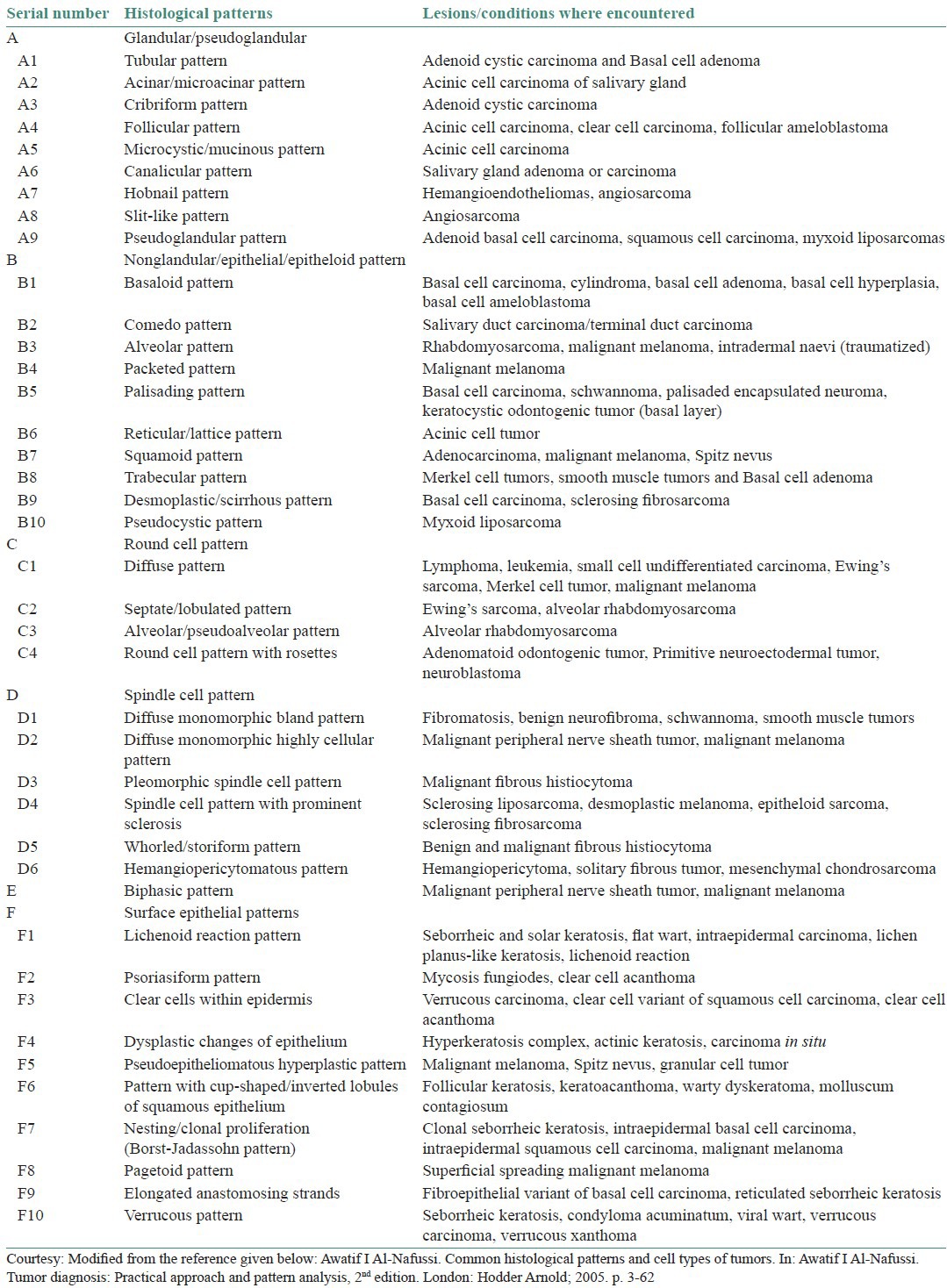

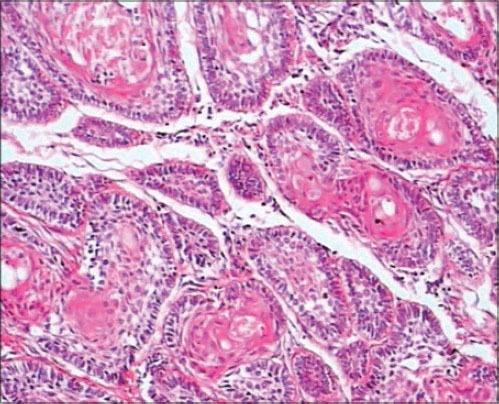

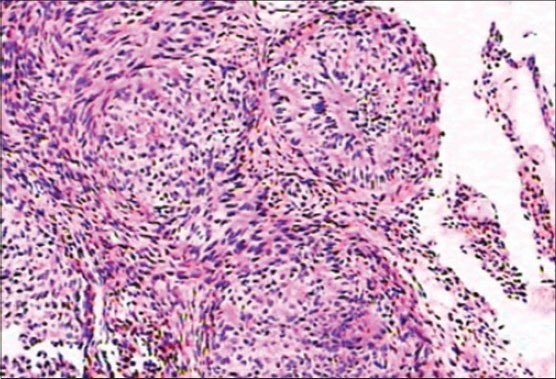

A1. Tubular pattern

This pattern shows the presence of single or double layer of proliferating epithelial cells forming elongated gland-like tubular structures where the cells are arranged in the form of a tube or duct. Example: Adenoid cystic carcinoma[5] [Figure 1] and Basal cell adenoma.

Figure 1.

A1-Tubular pattern in Adenoid cystic carcinoma (H&E stain, ×400). (Courtesy-Department of Oral and Maxillofacial Pathology, VSPM's DCRC, Nagpur)

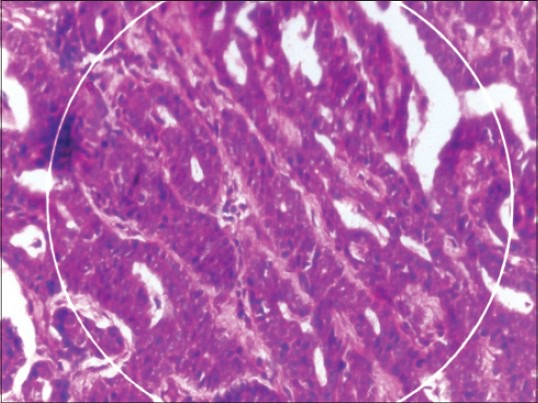

A2. Acinar/microacinar pattern

Neoplastic cells in this pattern form small rounded spaces (acini) lined by epithelial layer. Example: Acinic cell carcinoma[6,7] [Figure 2].

Figure 2.

A2 and A5-Acinar pattern and microcystic pattern in acinic cell carcinoma. (H&E stain, ×400). [Courtesy-http://moon.ouhsc.edu/kfung/JTY1/opaq/PathQuiz/PQ-Images/E0A003-3.gif (seen on 14/2/2014)]

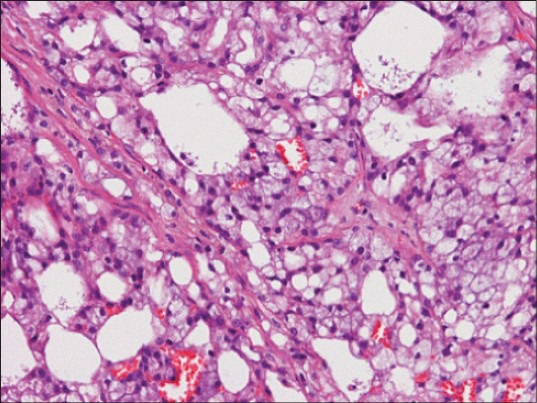

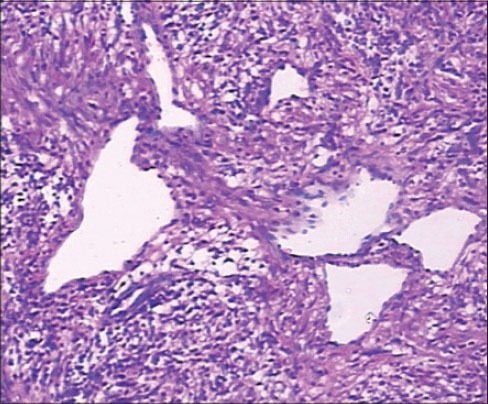

A3. Cribriform pattern

Arrangement of the cells in this pattern is in the form of multiple perforations, like a sieve. The proliferating neoplastic cells form cyst-like spaces of varying sizes, which may or may not be filled with material (basement membrane like/mucinous). These cyst-like spaces are surrounded by uniform monomorphic round cells. Example: Adenoid cystic carcinoma[5,8,9] [Figure 3].

Figure 3.

A3 and B10-Cribriform and pseudocystic pattern in Adenoid cystic carcinoma (H&E stain, ×400). (Courtesy-Department of Oral and Maxillofacial Pathology. VSPM's DCRC, Nagpur. DCRC = Dental College and Research Center)

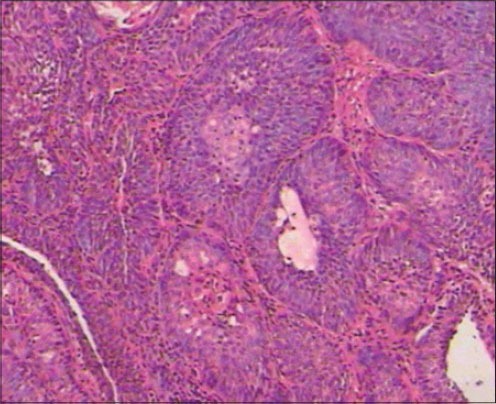

A4. Follicular pattern

This pattern is characterized by the presence of proliferating cells forming follicles. These follicles show peripherally located palisaded cells and centrally placed cells of different morphology.

Examples: Acinic cell carcinoma,[7] clear cell carcinoma[10] and follicular ameloblastoma[11,12] [Figure 4].

Figure 4.

A4-Follicular or squamoid pattern seen in Acanthomatous Ameloblastoma (H&E stain, ×100). (Courtesy-Department of Oral and Maxillofacial Pathology. VSPM's DCRC, Nagpur. DCRC = Dental College and Research Center)

In follicular ameloblastoma, ameloblastic follicles show peripherally located tall columnar ameloblast-like cells and centrally placed stellate reticulum-like cells.

A5. Microcystic/mucinous pattern

Tumor cells show numerous small cyst-like spaces that vary from several microns to a mm or more in size creating a lattice-like or sieve–like appearance. Microcystic spaces surrounded by the tumor cells are filled with eosinophilic proteinaceous material.

Examples: Acinic cell carcinoma[6,7] [Figure 2], Papillary cystadenocarcinoma, Mucoepidermoid carcinoma.

A6. Canalicular pattern

This pattern depicts the presence of neoplastic cells proliferating and forming elongated and branching structures simulating ‘channels’ that are lined by epithelium and separated by fibrous tissue. Examples: Canalicular adenoma or canalicular carcinoma.[13]

A7. Hobnail pattern

Literal meaning of hobnail is a short nail with thick head. The pattern shows neoplastic cells with abundant cytoplasm and nuclei protruding beyond the cytoplasm of the cell. Commonly seen in vascular tumors where nuclei appear to be protruding into the lumen of vessels.

Examples: Hemangiomas,[3,4] angiosarcoma[14] and hemangioendotheliomas[15] [Figure 5].

Figure 5.

A7-Hobnail pattern in Haemangioendothelioma (H&E stain, ×400). (Courtesy-Department of Oral and Maxillofacial Pathology, VSPM's DCRC, Nagpur

A8. Slit-like pattern

This pattern can be represented by glandular and nonglandular tumors, mainly angiosarcoma,[14] wherein the tumor cells proliferate and form slit-like spaces or narrow opening due to abortive vessel formation [Figure 6].

Figure 6.

A8-Slit-like pattern seen in Angiosarcoma (H&E stain, ×100). (Courtesy-Department of Oral and Maxillofacial Pathology, VSPM's DCRC, Nagpur)

A9. Pseudoglandular pattern

The neoplastic cells form gland-like structures (false glands) due to acantholysis and degeneration of the cells or accumulation of basement membrane-like material within the cellular proliferation.

Examples: Adenomatoid odontogenic tumor,[3] adenoid basal cell carcinoma[16] and myxoid liposarcoma[17] [Figure 7].

Figure 7.

A9, B1-basaloid pattern in Basal cell carcinoma (H&E stain, ×100). (Courtesy-Department of Oral and Maxillofacial Pathology. VSPM's DCRC, Nagpur)

B. Nonglandular epithelial/epithelioid pattern Table 1

In this category, no gland formation is shown by the epithelial/epithelioid tumor cells; however, the tumor might be of glandular nature. It includes the following subpatterns:

B1. Basaloid pattern

It includes neoplastic cells predominantly like basal cells, having well-defined morphology. They are round to oval, elongated cells present in nests with hyperchromatic nuclei and scanty cytoplasm. These basaloid cells may not be basal in position or origin.

Examples: Cylindroma,[5,6,7] basal cell ameloblastoma,[12] basal cell carcinoma[18] and basal cell adenoma.[19] [Figure 7].

B2. Comedo pattern

The characteristic feature of this pattern is the presence of central coagulative necrosis that is surrounded by well-defined nests of proliferating epithelial cells.

Example: Salivary duct carcinoma[20] [Figure 8].

Figure 8.

B2Comedo pattern in Salivary duct carcinoma. (H&E stain, ×100). [Courtesy-http://www.webpathology.com/image.asp?case=122&n=1 (seen on 4/3/14)]

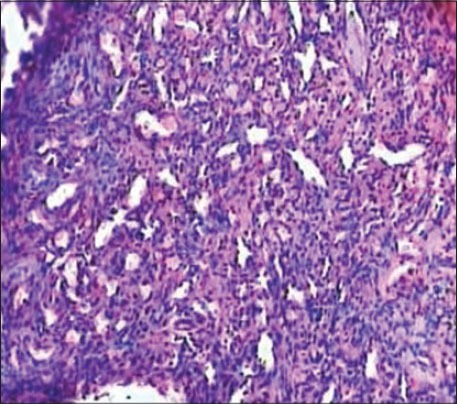

B3. Alveolar pattern

It exhibits a single layer of neoplastic cells that adheres to dense fibrous septa with central cells showing loss of cohesion and individual tumor cell necrosis is seen between the fibrous septa resulting in a lung-like alveolar appearance. Example: Malignant melanoma,[21] traumatized intradermal nevi[21] and rhabdomyosarcoma[22] [Figure 9].

Figure 9.

B3, C2, C3-Alveolar and round cell pattern in Alveolar Rhabdomyosarcoma (H&E stain, ×200). (Courtesy: Enzinger FM, Weiss SW. Textbook of Soft Tissue Tumors, fourth edition. St Louis: CV Mosby; 1995)

B4. Packeted pattern

The proliferating neoplastic cells form small round packets supported by a delicate vascular network or by supporting cells. Example: malignant melanoma[21] and round cell tumors.[23]

B5. Palisading pattern

Tumor cells show parallel side by side alignment of nuclei. Commonly seen in palisaded encapsulated neuroma,[3] keratocystic odontogenic tumor (shows palisading of basal cell layer),[4] ameloblastoma showing peripheral ameloblast-like cells,[11] basal cell carcinoma[18] and schwannoma[24] [Figure 10].

Figure 10.

B5-Palisading pattern in Schwannoma (H&E stain, ×400). (Courtesy: Enzinger FM, Weiss SW. Textbook of Soft Tissue Tumors, fourth edition. St Louis: CV Mosby; 1995)

B6. Reticular/Lattice pattern

In this pattern the neoplastic cells proliferate and give a net-like appearance to the lesion showing multiple spaces of varying sizes in between the cells. Example: A cinic cell tumor of salivary gland.[4,7]

B7. Squamoid pattern

Tumor cells have epithelial/epithelioid morphology with abundant hyalinized cytoplasm. Marked cytoplasmic eosinophilia may be encountered in certain tumors, which gives a squamous look to the tumor; However, they might not be necessarily squamous in origin.

Examples: Squamous odontogenic tumor,[4] adenocarcinomas,[20] malignant melanoma[21] and Spitz nevus.[25] and Acanthomatous Ameloblastoma.

B8. Trabecular pattern

Trabecula is a Latin word that means ‘little beam’. In a tumor, the neoplastic epithelium is seen in the form of strands that is separated from the connective tissue and forms a network or trabeculae of variable sizes.

Examples: Smooth muscle tumors,[3] sclerosing lymphoma,[4] merkel cell tumors,[26] polymorphous low-grade adenocarcinoma[27] and basal cell adenoma.

Plexiform: (Means ‘network/tangle’ [Latin]) it is a variation of trabecular pattern that is characterized by the presence of anastomosing chords and strands of proliferating tumor cells forming a network/mesh-like pattern.

Examples: Plexiform ameloblastoma[11,12] and focally in pleomorphic adenoma.[28]

B9. Desmoplastic/scirrhous pattern

Desmoplasia implies to the increased collagen production and fibrosis, whereas scirrhous means hard dense growth arising from connective tissue. This pattern shows disfigured and compressed structures embedded in a dense collagen fiber stroma.

Examples: Desmoplastic ameloblastoma,[12] basal cell carcinoma,[18] sclerosing fibrosarcoma[29] and various oral fibromatosis.[29]

B10. Pseudocystic pattern

These are the cystic spaces of various sizes and shapes, resulting from degenerative changes within the tumor. It is seen in Adenoid cystic carcinoma and myxoid liposarcoma[17] [Figure 3].

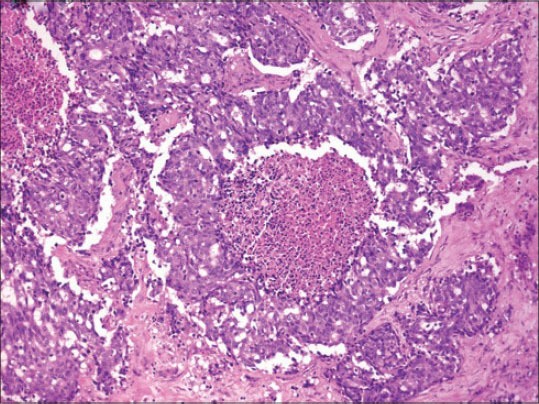

C. Round cell pattern [Table 1]

Round cell pattern is exhibited by the lesions showing predominant population of small round cells with basophilic nuclei and scanty or no cytoplasm. Various subpatterns include the following:

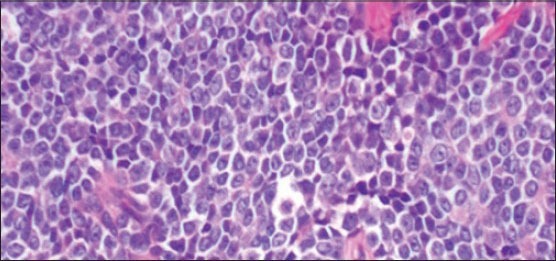

C1. Diffuse round cell pattern

Neoplastic round cells are present in sheets and do not show any distinct arrangement in particular. Examples: Lymphoma,[4] leukemia,[4] small cell undifferentiated carcinoma,[4] malignant melanoma,[21] Merkel cell tumor[26] and Ewing's sarcoma[30] [Figure 11].

Figure 11.

C1-Diffuse round cell pattern in Ewing's sarcoma (H&E stain, ×400). [Courtesy: http://www.webpathology.com/image.asp?case=340&n=5 (seen on 4/3/14)]

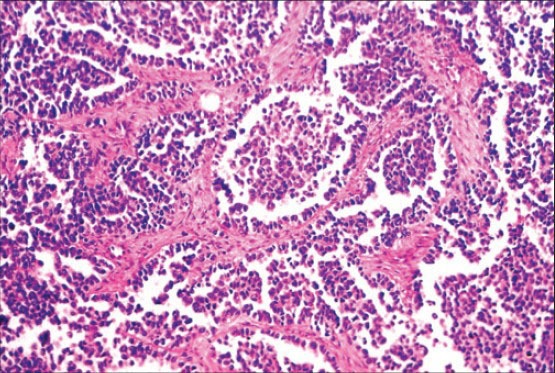

C2. Septate/lobulated round cell pattern

Small round cells are seen in the form of sheets that are divided by fibrous septae. Examples: Ewing's sarcoma[30] and alveolar rhabdomyosarcoma[31] [Figure 9].

C3. Alveolar/pseudoalveolar round cell pattern

It shows focal areas of poor cohesion of round cells. Examples: peripheral neuroectodermal tumor of infancy (PNET)[4] and alveolar rhabdomyosarcoma[31] [Figure 9].

C4. Round cell pattern with rosettes

Rosette means resembling a flower, where the cells are radially arranged around the center. In this pattern, round cells show characteristic rosette formation.

Examples: Adenomatoid odontogenic tumor, PNET[4] and rhabdomyosarcoma[22] [Figure 12].

Figure 12.

C4-Rossette pattern in Adenomatoid odontogenic tumor (H&E Stain, ×200). (Courtsey-Department of Oral and Maxillofacial Pathology, VSPM's DCRC, Nagpur)

D. Spindle cell pattern [Table 1]

It involves the lesions showing the predominance of spindle-shaped cells. Lesions may be hyper or hypocellular. It includes the following subpatterns:

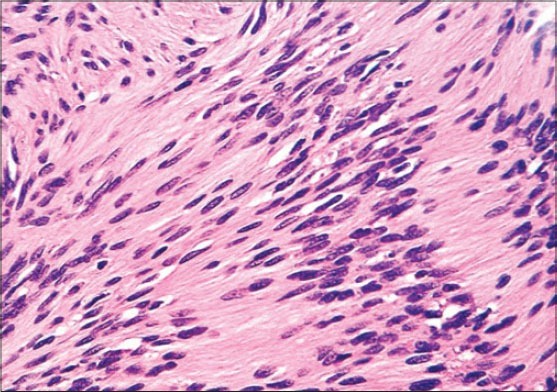

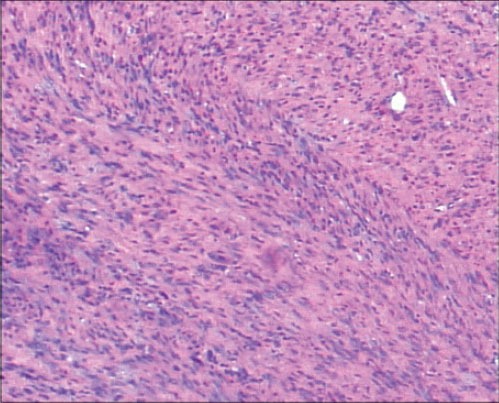

D1. Diffuse monomorphic bland spindle cell pattern (fibromatosis pattern)

This pattern exhibits uniform spindle-shaped cells, mainly mature fibroblasts with bland cytoplasm that are arranged loosely. The cells are small with prominent nuclei embedded in a collagenous stroma in sweeping pattern.

Examples: Smooth muscle tumors,[4] fibromatosis,[29] schwannoma[24,32] and benign neurofibroma.[32]

D2. Diffuse monomorphic highly cellular spindle cell pattern (fibrosarcoma pattern)

Neoplastic cells proliferate and form fascicles that intersect at acute angles in a characteristic ‘herring-bone’ arrangement. Tumors are highly cellular showing pleomorphism, mitoses and necrosis.

Examples: Fibrosarcoma, malignant melanoma[21] and malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumor[33] [Figure 13].

Figure 13.

D2-Spindle cell pattern in Fibrosarcoma.(H&E Stain, ×400). (Courtsey-Department of Oral and Maxillofacial Pathology, VSPM's DCRC, Nagpur)

D3. Pleomorphic spindle cell pattern (malignant fibrous histiocytoma pattern)

This is a highly variable pattern showing frequent transition from storiform to pleomorphic spindle cell pattern. It shows plump spindle-shaped cells resembling fibroblasts arranged in a cartwheel pattern around narrow slit-like vessels. Also, plump round histiocytic cells are seen that are arranged haphazardly. Large number of multinucleated bizarre giant cells are also seen along with numerous mitotic figures.

Examples: Spindle cell carcinoma,[4] malignant melanoma,[21] desmoplastic Spitz nevus,[25] malignant fibrous histiocytoma[34] and pleomorphic liposarcoma.[35]

D4. Spindle cell pattern with prominent sclerosis

This pattern also includes the tumors showing excessive sclerosis, hence have a less aggressive behavior. Examples: Epithelioid sarcoma,[4] desmoplastic melanoma,[21] ancient schwannoma,[24] sclerosing fibrosarcoma[29] and sclerosing liposarcoma.[35]

D5. Storiform and whorled pattern

Storiform means ‘matting’ (storia). It is characterized by the presence of neoplastic cells that radiate away from the center like ‘wheel spokes’ or a ‘cartwheel’ whorling arrangement.

Examples: Sclerotic fibroma,[4] fibromatosis[29] and benign/malignant fibrous histiocytoma.[34]

In the whorled pattern, the tumor cells are arranged radially in whorls around an imaginary stem. This is seen in fibromyxoid sarcoma,[4] fibrosarcoma[29] and dedifferentiated liposarcoma[35] [Figure 14].

Figure 14.

D5-Whorled pattern in Fibromyxoid sarcoma (H&E stain, ×400). (Courtesy: Enzinger FM, Weiss SW. Textbook of Soft Tissue Tumors, fourth edition. St Louis: CV Mosby; 1995)

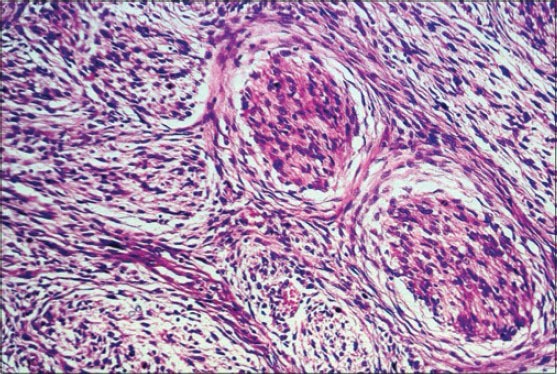

D6. Spindle cell populations with hemangiopericytomatous pattern

The cells in this pattern range from round/oval to slightly spindle. It shows a rich vascular pattern composed of large and small vessels lined by single layer of flattened endothelial cells that are typically angulated or forked forming the characteristic ‘staghorn’ pattern.

Examples: Mesenchymal chondrosarcoma,[4] solitary fibrous tumor[4] and hemangiopericytoma[36] [Figure 15].

Figure 15.

D6-Staghorn pattern in Haemangiopericytoma (H&E stain, ×100). (Courtesy-Department of Oral and Maxillofacial Pathology, VSPM's DCRC, Nagpur

E. Biphasic pattern [Table 1]

Biphasic pattern

It includes the lesions with spindle cell population showing two different components, either epithelial or glandular. Tumors may be benign or malignant. The benign biphasic pattern shows lesions having both epithelial and glandular components that appear bland and classically seen in pleomorphic salivary gland adenoma.[28]

Malignant bi/triphasic tumors show either epithelial or glandular or both the components that appear to be prominent and typical examples are malignant melanomas[21] and malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumor.[32]

F. Surface epithelial patterns associated with or affected by neoplastic process [Table 1]

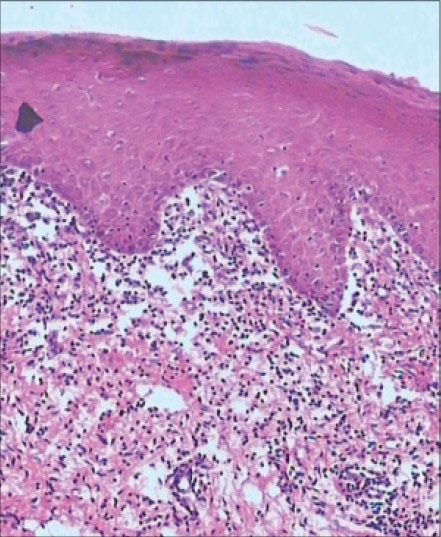

F1. Lichenoid reaction pattern

It shows a band of inflammatory cells along with degeneration of basal cells. Epidermal lesions that may show this pattern include seborrheic keratosis,[37] solar keratosis, flat wart, intraepidermal carcinoma, lichen planus and lichenoid reaction[3,4] [Figure 16].

Figure 16.

F1-Lichenoid reaction pattern in Lichen planus (H&E stain, ×100). (Courtesy-Department of Oral and Maxillofacial Pathology. VSPM's DCRC, Nagpur)

F2. Psoriasiform reaction pattern

This pattern shows the epithelium showing elongation of rete ridges and epidermal hyperplasia.

Example: Mycosis fungoides[4] and clear cell acanthoma.[3,4]

F3. Clear cells (koilocytes) within the epidermis

This pattern includes lesions that exhibit large population of cells having clear or pale staining cytoplasm referred to as clear cell. Presence of glycogen or mucin and virally infected cells also show ballooning degeneration, giving cells clear appearance or processing artifacts also gives typical clear appearance. Example: Clear cell acanthoma,[4] clear cell variant of squamous cell carcinoma,[38] verrucous carcinoma,[39] verrucous hyperplasia[40] and proliferative verrucous leukoplakia.[40]

F4. Dysplastic changes of epidermis or squamous mucosa

The pattern shows characteristic dysplastic changes of the epidermis or mucosa that includes proliferation of immature neoplastic cells. Cells exhibit pleomorphism, hyperchromatism, loss of polarity and increased and abnormal mitotic activity.

Examples: Actinic keratosis,[4] carcinoma in situ, verrucous hyperplasia[40] and proliferative verrucous leukoplakia.[40]

F5. Pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplastic pattern

This pattern shows proliferative changes in the epithelium in response to chronic irritation, trauma, cryotherapy, chronic lymphoedema and various dermal inflammatory processes. The epithelium has a bland appearance that should not be mistaken for carcinoma. The epidermis shows marked hyperplasia with down growth of rete ridges and expansion that simulates epidermoid carcinoma, but there is no true invasion of the epithelial cells into the underlying connective tissue. There is minimal cytological atypia and no abnormal mitotic activity is seen.

Examples: Necrotizing sialometaplasia,[4] malignant melanoma,[21] Spitz nevus[25] and granular cell tumor[41] [Figure 17].

Figure 17.

F5-Pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplastic pattern in Necrotizing sialometaplasia. (H and E Stain, ×100). (Courtesy-Sena Costa, et al. Journal of Medical Case Reports 2012;6:56)

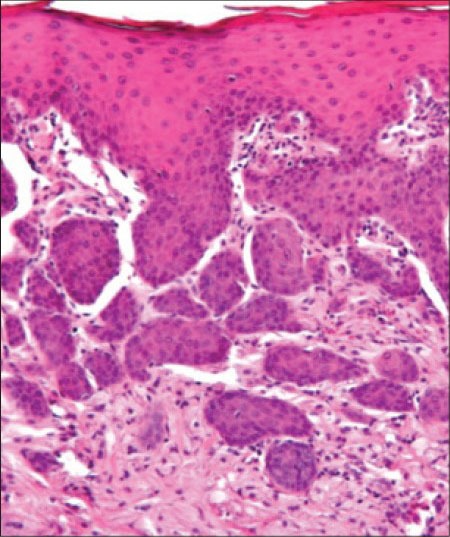

F6. Pattern with ‘cup-shaped’ or inverted lobules of squamous epithelium

The surface epithelium is thrown into one or more irregular or cup-shaped invaginations that may show hyperplasia or dysplasia. This pattern is depicted by many epithelial lesions. Examples: keratoacanthoma,[42] warty dyskeratoma[43] and molluscum contagiosum.[44]

F7. Nesting or clonal proliferation ‘Borst–Jadassohn’ phenomenon

In this pattern, the proliferating epithelial cells having different morphology and not necessarily the same origin from other surrounding cells are present in groups or small nests. Borst–Jadassohn phenomenon is a term used to denote intraepidermal aggregation of basaloid or epitheloid cells. Examples: Intraepidermal basal cell carcinoma,[18] malignant melanoma,[21] clonal seborrheic keratosis[37] and intraepidermal squamous cell carcinoma.[38]

F8. Pagetoid pattern

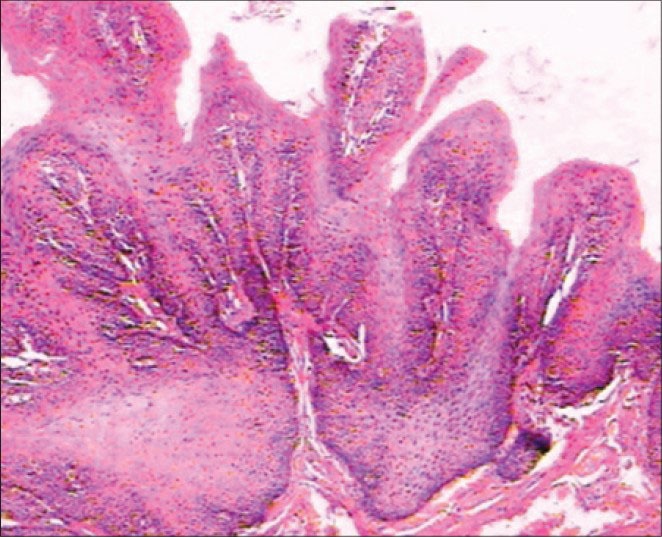

It exhibits an upward spread. It shows the presence of tumor cells that are present in the form of nests of single cells at the junction of dermis and epidermis or in all the epidermal layers. Examples: Superficial spreading malignant melanoma.[21]

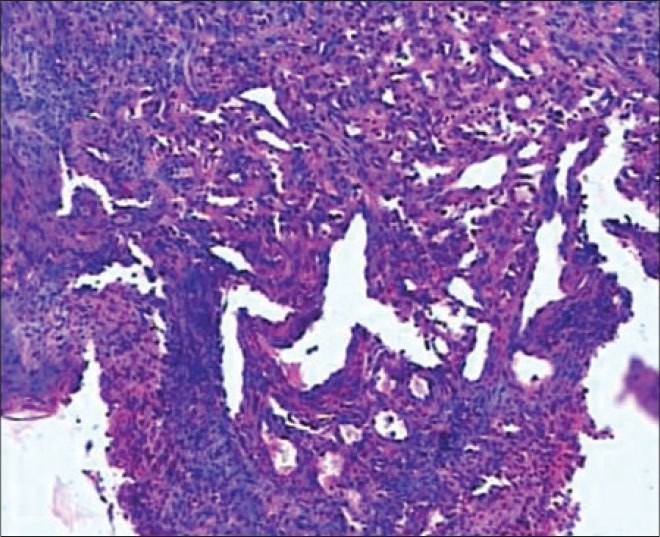

F9. Elongated anastomosing strands

The proliferating cells are basaloid epithelial cells that form numerous long and thin anastomosing cords and are connected to the epidermis. Example: Fibroepithelial variant of basal cell carcinoma[18] [Figure 18].

Figure 18.

F9-Elongated anastomosing strands pattern in Fibroepithelial polyp. (H&E stain, ×100). (Courtesy- Department of Oral and Maxillofacial Pathology. VSPM's DCRC, Nagpur)

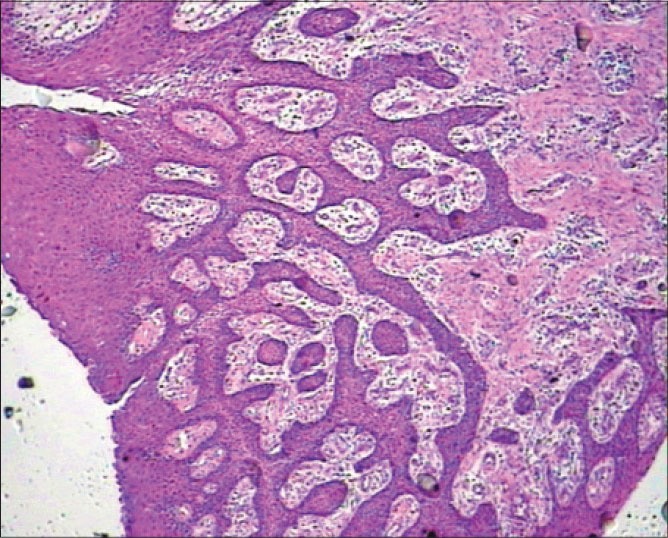

F10. Verrucous pattern

This pattern shows an exophytic papillary growth along with acanthosis and hyperkeratosis. Examples: Seborrheic keratosis,[37] verrucous carcinoma,[39] viral wart,[40] verrucous xanthoma,[40] verrucous hyperplasia,[40] proliferative verrucous leukoplakia[40] and condyloma acuminatum[45] [Figure 19] and squamous papilloma.

Figure 19.

F10-Verrucous or papillary pattern in squamous papilloma (H&E stain, ×100). (Courtesy-Department of Oral and Maxillofacial Pathology. VSPM's DCRC, Nagpur. DCRC = Dental College and Research Center)

Undifferentiated tumor patterns

The proliferating neoplastic cells form large solid areas that do not show any characteristic architecture. Cells are large, uniform and pleomorphic. This pattern is encountered mostly in undifferentiated carcinomas, sarcomas and malignant melanomas.[4] The tumor cells are poorly differentiated and the lesions do not show any relevant clinical, radiological and morphological features to arrive at a diagnosis. Hence, definitive diagnosis of such cases is done using adjunct techniques like immunohistochemistry, electron microscopy, molecular and biochemical methods. Identification of these undifferentiated tumor patterns can also be done by studying the epithelial mesenchymal interaction via the use of various tumor markers like K-ras and c-myc oncogenes, transforming factors TGF-α, TGF-β, E-cadherin, cluster of differentiation (CD) 44, matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs) and tissue inhibitors of metalloproteinases (TIMPs). Epithelial differentiation can be well understood by the use of cytokeratins. Cathepsin D promotes tumor invasion and metastasis and it is a potent independent predictor of cervical lymph node metastasis.[46]

CONCLUSION

Identification and accurate diagnosis of a tumor is an art and necessitates complete knowledge of cellular, biochemical and molecular events and pathogenesis of that tumor. The tumor patterns have been classified in seven broad categories, namely, the glandular/pseudoglandular pattern, nonglandular epithelial/epitheloid pattern, round cell pattern, spindle cell pattern, biphasic pattern, surface epithelial patterns associated with or affected by neoplastic process and the undifferentiated tumor pattern.

Although the undifferentiated tumor remains as the challenge, these patterns help the histopathologist to reach at the diagnosis. However, these histological patterns are not always diagnostic, there may be variations present along with the subpatterns. Therefore with patterns seen on hematoxylin and eosin stained sections, diagnosis can be confirmed by special stains, immunohistochemistry and different molecular diagnostic aids.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Tarin D, Thompson EW, Newgreen DF. The fallacy of epithelial mesenchymal transition in neoplasia. Cancer Res. 2005;65:5996–6000. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-0699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Nawshad A, LaGamba D, Polad A, Hay ED. Transforming growth factor-beta signaling during epithelial-mesenchymal transformation: Implications for embryogenesis and tumor metastasis. Cells Tissues Organs. 2005;179:11–23. doi: 10.1159/000084505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ashley DJB. Tumors of integument, tumors of nervous system, epithelial tumors of oral mucous membrane, tumors of the jaws, tumors of salivary glands. In: David J.B Ashley., editor. Evan's histological appearances of tumors. 4th edition. London: Churchill Livingstone; 1990. pp. 389–630. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Awatif I Al-Nafussi. Awatif I Al- Nafussi. Tumor diagnosis: Practical approach and pattern analysis. 2nd edition. London: Hodder Arnold; 2005. Common histological patterns and cell types of tumors; pp. 3–62. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rapidis AD, Givalos N, Gakiopoulou H, Faratzis G, Stavrianos SD, Vilos GA, et al. Adenoid cystic carcinoma of the head and neck. Clinicopathological analysis of 23 patients and review of the literature. Oral Oncol. 2005;41:328–35. doi: 10.1016/j.oraloncology.2004.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Guha S, Guha R, Manikantan K, Sharan R, Arun P. Synchronous bilateral acinic cell carcinoma of the parotid. J Cancer Sci. 2012;4:92–3. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Betkowski A, Cyran-Rymarz A, Domka W. Bilateral acinar cell carcinoma of the parotid gland. Otolaryngol Pol. 1998;52:101–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Szanto PA, Luna MA, Tortoledo ME, White RA. Histologic grading of adenoid cystic carcinoma of the salivary glands. Cancer. 1984;54:1062–9. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19840915)54:6<1062::aid-cncr2820540622>3.0.co;2-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Perzin KH, Gullane P, Clairmont AC. Adenoid cystic carcinomas arising in salivary glands: A correlation of histologic features and clinical course. Cancer. 1978;42:265–82. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(197807)42:1<265::aid-cncr2820420141>3.0.co;2-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Simpson RH, Sarsfield PT, Clarke T, Babajews AV. Clear cell carcinoma of minor salivary glands. Histopathology. 1990;17:433–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2559.1990.tb00764.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kim SG, Jang HS. Ameloblastoma: A clinical, radiographic, and histopathologic analysis of 71 cases. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2001;91:649–53. doi: 10.1067/moe.2001.114160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hertog D, Bloemena E, Aartman IH, Van-der-Waal I. Histopathology of ameloblastoma of the jaws; some critical observations based on a 40 years single institution experience. Med Oral Patol Oral Cir Bucal. 2012;17:e76–82. doi: 10.4317/medoral.18006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Karunakaran K, Jeya pradha D, Kiran kumar, Rajeshwar G. Canalicular Adenoma of Palate-A Case Report. JIADS. 2010;1:43–5. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Terada T. Angiosarcoma of the oral cavity. Head Neck Pathol. 2011;5:67–70. doi: 10.1007/s12105-010-0211-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Weiss SW, Goldblum JR. Hemangioendothelioma: Vascular tumors of intermediate malignancy. In: Marc Strauss., editor. Enzinger and Weiss's soft tissue tumors. 4th edition. St. Louis, Missouri: Mosby; 2001. pp. 891–915. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tambe SA, Ghate SS, Jerajani HR. Adenoid type of basal cell carcinoma: Rare histopathological variant at an unusual location. Indian J Dermatol. 2013;58:159. doi: 10.4103/0019-5154.108080. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pedrinaci IZ, Jurado JM, Carrillo J, Molina MC. Trabectedin as second-line treatment in metastatic myxoid liposarcoma: A case report. J Med Case Rep. 2012;6:424. doi: 10.1186/1752-1947-6-424. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Betti R, Bruscagin C, Inselvini E, Crosti C. Basal cell carcinomas of covered and unusual sites of the body. Int J Dermatol. 1997;36:503–5. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-4362.1997.00139.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.González-García R, Nam-Cha SH, Muñoz-Guerra MF, Gamallo-Amat C. Basal cell adenoma of the parotid gland. Case report and review of the literature. Med Oral Patol Oral Cir Bucal. 2006;11:E206–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gupta S, Gupta K, Ram H, Gupta OP. Salivary Duct Carcinoma of the Minor Salivary Gland: A Rare Case Report. J Interdiscipl Histopathol. 2013;1:223–226. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Massi G, Lebiot PE. 1st edition. Germany: Springer; Steinkopff Darmstad t; 2004. Histological diagnosis of nevi and melanoma. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Dagher R, Helman L. Rhabdomyosarcoma: An overview. Oncologist. 1999;4:34–44. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chang F. Desmoplastic small round cell tumours: Cytologic, histologic and immunohistochemical features. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2006;130:728–32. doi: 10.5858/2006-130-728-DSRCTC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kurtkaya-Yapicier O, Scheithauer B, Woodruff JM. The pathobiologic spectrum of Schwannomas. Histol Histopathol. 2003;18:925–34. doi: 10.14670/HH-18.925. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sulit DJ, Guardiano RA, Krivda S. Classic and atypical Spitz nevi: Review of literature. Cutis. 2007;79:141–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wang TS, Byrne PJ, Jacobs LK, Taube JM. Merkel cell carcinoma: Update and review. Semin Cutan Med Surg. 2011;30:48–56. doi: 10.1016/j.sder.2011.02.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Olusanya AA, Akadiri OA, Akinmoladun VI, Adeyemi BF. Polymorphous low grade adenocarcinoma: Literature review and report of lower lip lesion with suspected lung metastasis. J Maxillofac Oral Surg. 2011;10:60–3. doi: 10.1007/s12663-011-0185-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Seifert G, Langrock I, Donath K. A pathological classification of pleomorphic adenoma of the salivary glands (author's transl) HNO. 1976;24:415–26. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Shetty Devi C, Urs. Aadithya B, Sikka S. Aggressive fibromatosis versus low grade fibrosarcoma-a diagnostic dilemma. Int J Pathology. 2010;8:30–3. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mukherjee A, Ray JG, Bhattacharya S, Deb T. Ewing's sarcoma of mandible: A case report and review of Indian literature. Contemp Clin Dent. 2012;3:494–8. doi: 10.4103/0976-237X.107454. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sekhar MS, Desai S, Kumar GS. Alveolar rhabdomyosarcoma involving the jaws: A case report. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2000;58:1062–5. doi: 10.1053/joms.2000.8754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Murarescu ED, Ivan L, Mihailovici MS. Neurofibroma, Schwannoma or a hybrid tumor of the peripheral nerve sheath? Rom J Morphol Embryol. 2005;46:113–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Guo A, Liu A, Wei L, Song X. Malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumors: Differentiation patterns and immunohistochemical features-a mini-review and our new findings. J Cancer. 2012;3:303–9. doi: 10.7150/jca.4179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Dalirsani Z, Mohtasham N, Falaki F, Bidram F, Nosratzeh T. Malignant fibrous histiocytoma of mandible: A review of literatures and report a case. Aust J Basic Appl Sci. 2011;5:936–42. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Henricks WH, Chu YC, Goldblum JR, Weiss SW. Dedifferentiated liposarcoma: A clinicopathological analysis of 155 cases with a proposal for an expanded definition of dedifferentiation. Am J Surg Pathol. 1997;21:271–81. doi: 10.1097/00000478-199703000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Florence SM, Willard CC, Palian CW. Hemangiopericytoma of the buccal region: A case report. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2001;59:449–53. doi: 10.1053/joms.2001.21886. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bhuiyan ZH. Seborrheic Keratosis: A case report. Orion Med J. 2007;26:441–2. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Markopoulos AK. Current aspects on oral squamous cell carcinoma. Open Dent J. 2012;6:126–30. doi: 10.2174/1874210601206010126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Terada T. Verrucous carcinoma of the oral cavity: A histopathologic study of 10 Japanese cases. J Maxillofac Oral Surg. 2011;10:148–51. doi: 10.1007/s12663-011-0197-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Gareth J, Thomas A, Barrett W. Papillary and verrucous lesions of the oral mucosa. Diagn Histopathol. 2009;15:279–85. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Bang KO, Bodhade AS, Dive AM. Congenital granular cell epulis of newborn. Den Res J (Isfahan) 2012;9:S136–8. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Al-Hoqail IA, Bhatt TA. Keratoacanthoma: An unusual presentation. Bahrain Med Bull. 2009;31:1–4. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Laskaris G, Sklavounou A. Warty dyskeratoma of the oral mucosa. Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1985;23:371–5. doi: 10.1016/0266-4356(85)90011-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Whitaker SB, Wiegand SE, Budnick SD. Intraoral molluscum contagiosum. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1991;72:334–6. doi: 10.1016/0030-4220(91)90228-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Gupta RR, Puri UP, Mahajan BB, Sahni SS, Garg G. Intraoral giant condyloma acuminatum. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2001;67:264–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ian Ellis. Immunocytochemistry in breast pathology. In: John D. Bancroft, Marilyn Gamble., editors. Theory and practice of histological techniques. 5th edition. London: Churchill Livingstone; 2002. pp. 499–516. [Google Scholar]