Until March 2011, the most common causes of death in Syria were similar to most countries in the world–cardiovascular disease followed by cancer.[1] This was changed dramatically when the conflict started, with more deaths from gunfire and artillery shelling reaching the top of the list.[2]

As the situation has escalated over the course of 2½ years, and with the increased numbers of cities and towns targeted by air strikes and artillery bombardment, the Syrian medical community reacted with initiatives to establish and organize makeshift medical facilities. Because hospitals and clinics have been damaged or destroyed, more “underground” and secretive approaches were taken for establishing health-care facilities and maintaining them. Most of the time these places were built underground to keep them safe from heavy weaponry attacks. Injured civilians still had to risk their lives to seek medical care because hospitals were either destroyed[3,4] or would refuse to care due to fear of security forces.

DIFFICULTIES ALONG THE WAY

Although Syrians initially named these facilities “field hospitals,” the majority were by far too basic and lacked necessary medical equipment, imaging utilities, medications, and specialist medical expertise to be able to adequately respond to mass casualty events. The siege set around many civilian areas further complicated the situation. In addition to banning food and fuel, medications and medical supplies were strictly prohibited. The blockade has rendered wide areas and hundreds of thousands of people devoid of basic medical care like vaccinations for children and medications for chronic diseases. As a result, this has raised fears for epidemics of many infectious diseases, including leishmaniasis, hepatitis A, cholera, and tuberculosis.[5,6] Some of these fears came true when a recent alarming report of several suspected cases of polio emerged and were later confirmed,[7] although polio had been eradicated in Syria since 1999.[8] Field hospital personnel were also at risk of many of these infectious diseases, particularly typhoid fever, brucellosis, and malnutrition. In fact, one of the authors got infected with typhoid fever when he was serving in one of the field hospitals. Medical personnel were also at greater risk during attacks, as in the case of the chemical weapon attack on Eastern Ghouta in August 2012 [Figure 1]. In this attack, most of the medical staff who responded to the incident were severely affected and some actually died.

Figure 1.

An emergency medical point in Daryya (Damascus Suburb) right after the chemical weapon attack on Damascus Suburbs on August 21, 2013

In addition, medical personnel or anyone carrying medical supplies, if caught, are at risk of punishment and potential execution on-site.[9] Health care professionals as a result must operate in hostile, threatening environments at great personal risk and peril. Furthermore, threats and dangers to medical professionals in Syria are not new and go back to the 1990s.[10]

STAFFING AND PERSONNEL

For all of the above-mentioned reasons, these Spartan field hospitals are considered heroic and are appreciated by civilians–especially since the vast majority of Syrian medical professionals fled the country.[11] For example, an estimated 2000 physicians were practicing in Aleppo city before the crisis, but only less than 100 remain now.[12,13] This shortage in physicians, especially the specialist ones, was reflected in the large number of injury deaths and limb amputations that would otherwise have been prevented should they have been handled early and more efficiently.

Since the early stages of the conflict, doctors were unable to operate safely in their regular working places to treat the conflict causalities. Instead, they would resort to secretly provide medical care to those injured. Although less efficient, this approach helped save hundreds of lives and organs, especially limbs and eyes.

Civilian volunteers helped operate and run the field hospitals alongside with the remaining few of Syrian doctors. In fact, most of those who offered nursing and other services at remaining hospitals were university students who came from nonmedical backgrounds such as economics, law, literature, electronics, and engineering. Medical and pharmacy students took a leading role in managing care of the injured. These unqualified personnel were faced with very complicated injuries and conditions that required very advanced surgical expertise. A number of consequences resulted from having personnel from non-medical backgrounds to manage these makeshift hospitals. Among these, particularly concerning are the mortality and morbidity associated with preventable complications.

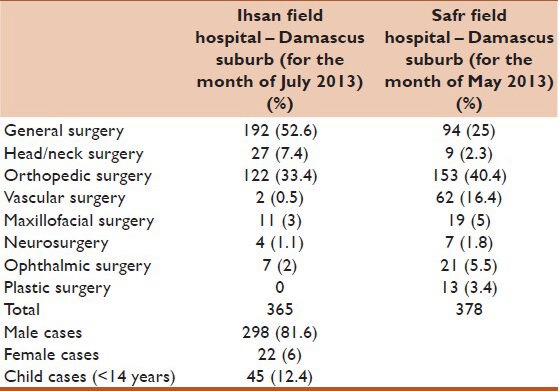

On many occasions, these nonmedical volunteers had to carry out the necessary work they knew very little about. For example, a nurse witnessed by one of the authors at one of the field hospitals was performing open abdominal surgeries–resecting bowel that had been perforated by bullets or shrapnel and suturing anastomoses. Table 1 provides a glimpse into the types of cases these hospitals are facing on a daily basis.

Table 1.

Examples of cases admitted to field hospitals

Syrian medical personnel working in these field hospitals have gained tremendous experience in establishing field hospitals fast enough to take care of the casualties, safe enough to secure them against air strikes and ground bombardment, and cheap enough with as little equipment as possible.

Hope for the future

However, the situation on the ground is bleak.[11] These field hospitals, though having become more sophisticated overtime, cannot replace well-established health care facilities by any means.[14] With repercussions directly affecting all countries in the region, as well as an indirect impact on international politics, the Syrian crisis requires urgent actions. A more organized work and support for the healthcare system is needed on multiple levels:

Direct collaboration of the international governmental and non-governmental efforts and organizations (e.g. UNICEF, International Red Cross, Doctors without Borders, and others)

Advocacy for preserving the remnant infrastructures and maintaining the minimum level of healthcare resources and services for the injured and displaced inside as well as outside Syria

Establishing a health surveillance and documentation task force for the detrimental health and environmental effects of the crisis

Promoting international awareness about the current hardship of the Syrian people and lobbying for an end to the conflict in such a way that would protect all human rights and independence of the country.

The Syrian crisis has left over 100,000 of the population dead[2,15] and around 8 out of 24 million Syrians became either displaced internally, or refugees in the neighboring countries,[16] according to UNHCR and NGOs. Local and international medical support by many organizations like the Syrian American Medical Society has been very vital,[11] but remains insufficient to meet the needs on the ground.[17] With minimal international medical and humanitarian aid going to those who are in desperate need inside Syria, the situation is likely to worsen in the near future. There is no better way to express Syrians’ frustration of the situation than the statement made by someone who survived the August 2012 chemical weapon attacks on Damascus Suburb, Amineh Sawan, when she said “tears are not in short supply, action is!.”[18]

REFERENCES

- 1.WHO. “Syrian Arab Republic: statistics.”. 2013. [Retrieved September 19, 2013]. from www.who.int/countries/syr/en .

- 2.“Syrian Revolution Martyr Database.”. [Retrieved October 22, 2013, Last accessed on 2013 Oct 21]. Available from http://syrianshuhada.com/?lang=en& .

- 3.Kherallah M, Alahfez T, Sahloul Z, Eddin KD, Jamil G. Health care in Syria before and during the crisis. Avicenna J Med. 2012;2:51–3. doi: 10.4103/2231-0770.102275. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mediterranean WROfE. Situation Reports for the Syrian Arab Republic. 2012. [Last cited on 2013 Sep 16]. Available from: http://www.emro.who.int/images/stories/eha/documents/sitrep_7_for_the_web.pdf .

- 5.Garfield R. Health professionals in Syria. Lancet. 2013;382:205–6. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)61507-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.ReliefWeb. “Early Warning and Reporting System (EWARS) Syria.”. 2013. [Retrieved October 22, 2013]. from http://reliefweb.int/sites/reliefweb.int/files/resources/Syria%20EWARS%20Weekly%20Bulletin%2C%20Week%20No.%201%2030%20Dec.%202012%20-%205%20Jan.%202013.pdf .

- 7.WHO-Global Alert and Response (GAR) Disease Outbreak News; 2013. Polio in the Syrian Arab Republic-Update. [Google Scholar]

- 8.World Health Organization Globar Alert and Response; 2013. Report of Suspected Polio Cases in the Syrian Arab Republic. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Al-Saiedi A. Physicians for human rights-Syria: Attacks on doctors, patients, and hospitals. 2011. [Last cited on 2013 Sep 19]. Available from: http://www.physiciansforhumanrights.org/library/reports/syria-attacks-on-doctors.html .

- 10.Kirschner RH, Hannibal K, Elahi M. Health professionals held as political prisoners in Syria. N Engl J Med. 1991;324:567. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199102213240818. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Society SAM. “Risking Lives to Save Lives”: SAMS Highlights the Ordeal of Syrian Medical Personnel in New Report. [Last cited on 2013 Oct 21]. Available from: http://www.sams-usa.net/site/riskinglivestosavelives .

- 12.Coutts A, Fouad FM. Response to Syria's health crisis - Poor and uncoordinated. Lancet. 2013;381:2242–3. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(13)61421-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.MacFarquhar N. The New York Times; [Last accessed on 2013 Mar 23]. Syria's Civil War, Doctors Find Themselves in Cross Hairs. http://www.nytimes.com/2013/03/24/world/middleeast/on-both-sides-in-syrian-war-doctors-are-often-the-target.html?pagewanted=all&_r=0 . [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sankari A, Atassi B, Sahloul MZ. Syrian field hospitals: A creative solution in urban military conflict combat in Syria. Avicenna J Med. 2013;3:84–6. doi: 10.4103/2231-0770.118467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Price M, Klingner J, Qtiesh A, Ball P. Updated Statistical Analysis of Documentation of Killings in the Syrian Arab Republic. 2013 [Google Scholar]

- 16.MacFarquhar N. The New York Times, The New York Times; [Last accessed on 2013 Mar 23]. Syria's Civil War, Doctors Find Themselves in Cross Hairs. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Syria: The neglected health crisis deepens. Lancet. 2013;382:743. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)61814-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.UN-WEB-TV. Voices from Syria-Special Event. [Last accessed on 2014 Jan 17]. Available from: http://www.webtv.un.org/watch/voices-from-syria-specialevent/3067731593001 .