Abstract

Retinoblastoma, the most common primary malignant intraocular tumor of childhood is a great success story in pediatric and ocular oncology. Pathology of retinoblastoma is important to guide the treatment modalities. Differentiated retinoblastoma is commonly seen in younger age group. Since a hundred years, we have been observing two typical true rosettes in retinoblastoma in the form of Flexner-Wintersteiner (FW) and Homer Wright (HW) rosettes and in many occasions pseudorosettes have been documented. In the present case report, a third new type of rosette was identified in a differentiated retinoblastoma which had an unusual anterior segment involvement.

Keywords: Differentiation, retinoblastoma, rosette

Retinoblastoma is the most common primary intraocular malignancy in childhood, occurring in one in 14,000-20,000 live births.[1,2] This tumor is thought to have a neuroblastic origin from the nucleated layers of the retina.[2] Pathologically, retinoblastoma consists of cells with round, oval, or spindle-shaped nuclei that are approximately twice the size of lymphocytes.[2,3] Varying degrees of retinal differentiation evident as Homer Wright (HW) and Flexner-Wintersteiner (FW) rosettes and photoreceptor differentiation as in fleurettes occurs in the tumor.[2,3] Differentiated forms are more evident in younger age groups and as the age advances, the less well-differentiated variety becomes common.[1,2,3,4,5]

We present a unique new type of rosette that has never been reported earlier. This new type of rosette is characteristically different from the FW and HW rosettes, and was observed in a child of 2 months age with unilateral retinoblastoma.

Case Report

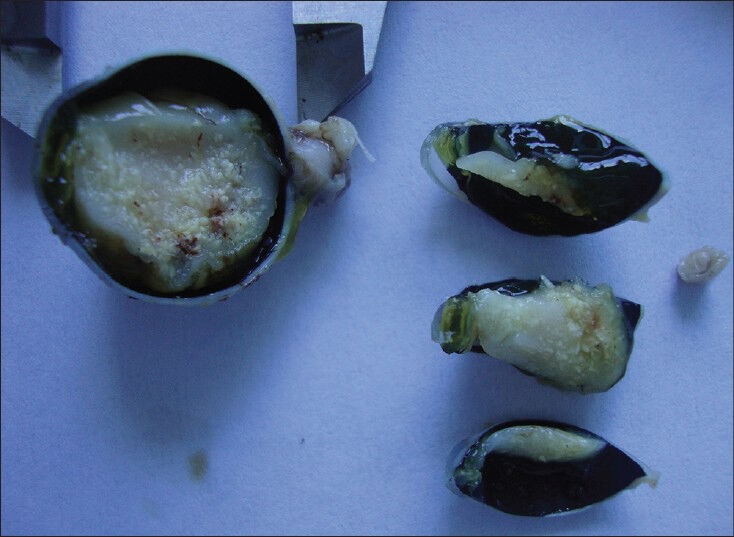

A 2-month-old female child, presented at a tertiary institute of northeast India with a white pupillary reflex in the left eye noticed by her parents. She was clinically diagnosed with retinoblastoma in the left eye and B-scan ultrasonography and computed tomography scan of the eye and orbit revealed an intraocular densely calcified soft tissue mass. Examination under general anesthesia prior to surgery confirmed the diagnosis of a unilateral intraocular retinoblastoma. Intraocular pressure was normal in both the eyes. Enucleation of the left eye with canthotomy and cantholysis to remove the enlarged globe was performed on the same day. The specimen was sent to the ocular pathology laboratory at the institute. After adequate fixation of the eyeball in 10% neutral buffered formalin, it was examined next day. The eyeball measured 20.84 mm anteroposteriorly, 19.6 mm horizontally, and 18.70 mm vertically. The cornea was 12.81 mm horizontally and 12.35 mm vertically; pupil was oval and measured 6.6 mm. Transected optic nerve measured 6.61 mm in length and 3.04 mm in diameter along with its meninges. There were no transillumination defects. The globe was sectioned vertically. A whitish, endophytic tumor occupying most of the vitreous cavity with specks of surface calcification was seen. Lateral calottes were cut separately and were submitted for histopathology. Separate transverse section of the distal end of optic nerve was cut and submitted for evaluation. Gross documentation was done [Fig. 1].

Figure 1.

Gross documentation of retinoblastoma specimen. Surface calcification can be noted

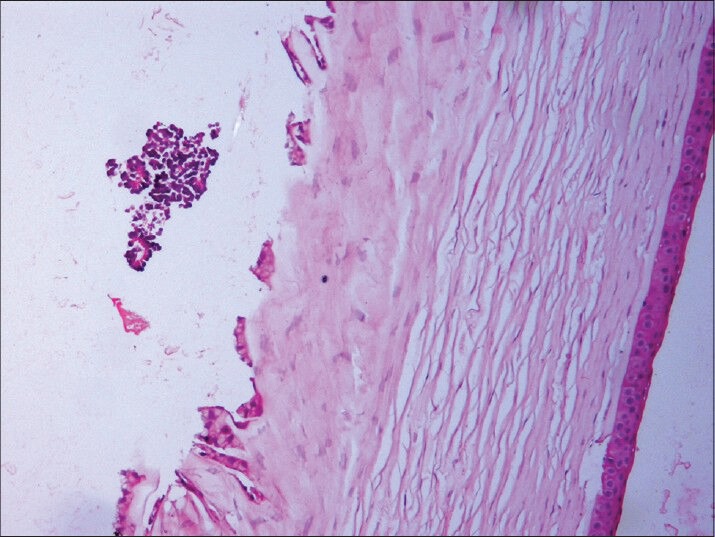

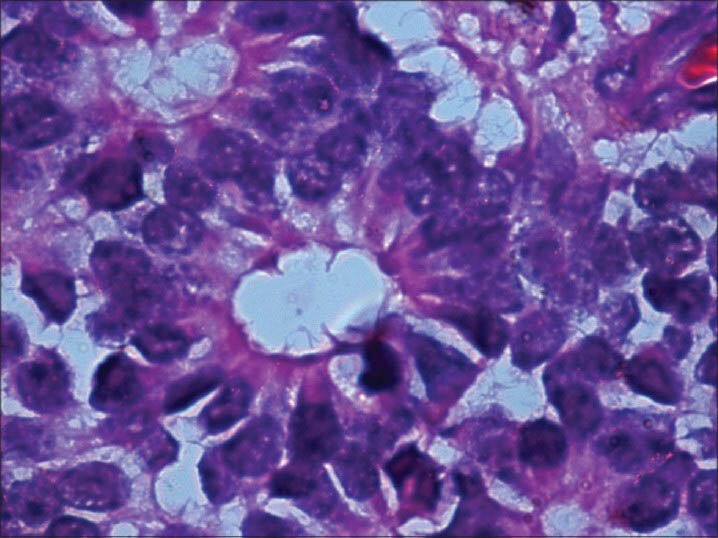

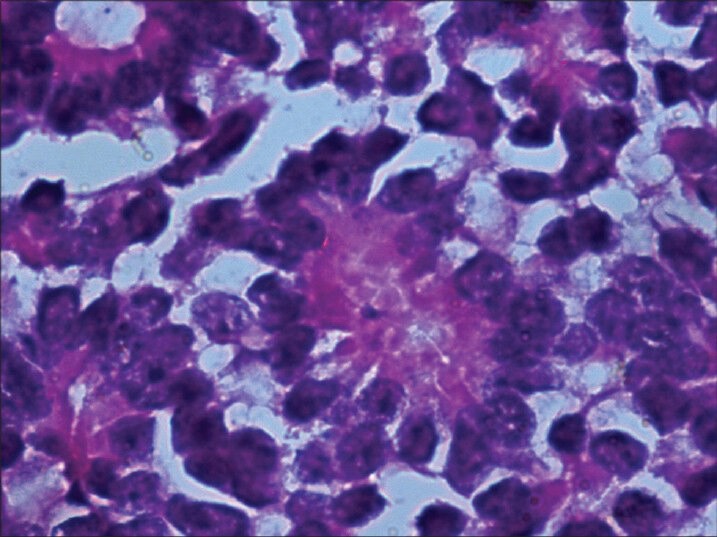

Microscopic study of the specimen in hematoxylin and eosin (H and E) stain showed that basophilic tumor cells infiltrated part of the corneal endothelium [Fig. 2]. Foci of tumor cells were also seen in the anterior chamber [Fig. 2]. A large endophytic tumor arising from retinal layers with FW [Fig. 3] and HW [Fig. 4] rosettes were seen. The tumor was differentiated. Interestingly, a new variety of rosette was seen on light microscopy which was characteristically different from FW and HW rosettes. These newly observed rosettes had basophilic cuboidal cells inside the lumens of the rosettes [Fig. 5]. Like FW rosettes, the lumens were stained with alcian blue as it contained hyaluronidase-resistant acid mucopolysaccharides (HR-AMP) [Figs. 6–8]. The tumor showed foci of minimal necrosis, with one area of isolated calcification [Fig. 2]. Lateral calottes did not show choroidal involvement in the specimen and distal end of the cut end of optic nerve was free from tumor invasion. Patient was reviewed by an oncologist at a regional cancer center (RCC).

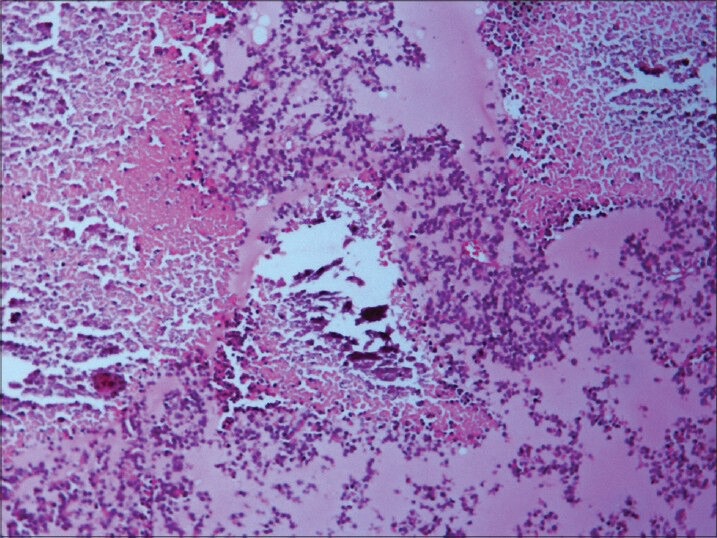

Figure 2.

Basophilic tumor cells infiltrating anterior chamber and endothelium of cornea (hematoxylin and esoin (H and E, ×100)

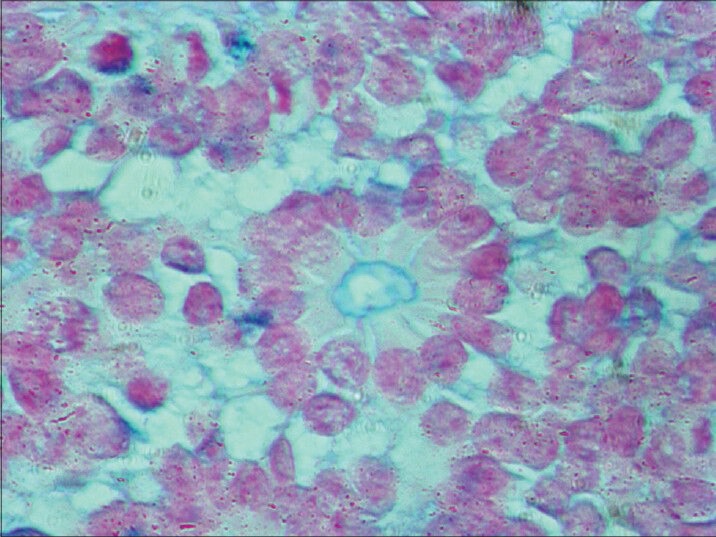

Figure 3.

Flexner-Wintersteiner (FW) rosette with clear lumen at the center (H and E, ×400)

Figure 4.

Homer Wright (HW) rosette with central tangle of neural filament. There is no clear lumen at the center (H and E, ×400)

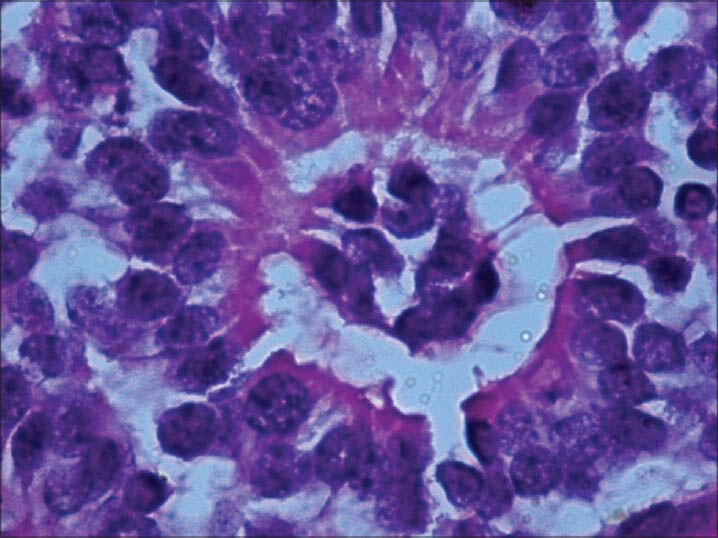

Figure 5.

Newly observed rosette with basophilic cuboidal cells occupying the center of lumen. Cytoplasmic extensions of the cells can be noted. (H and E, × 400)

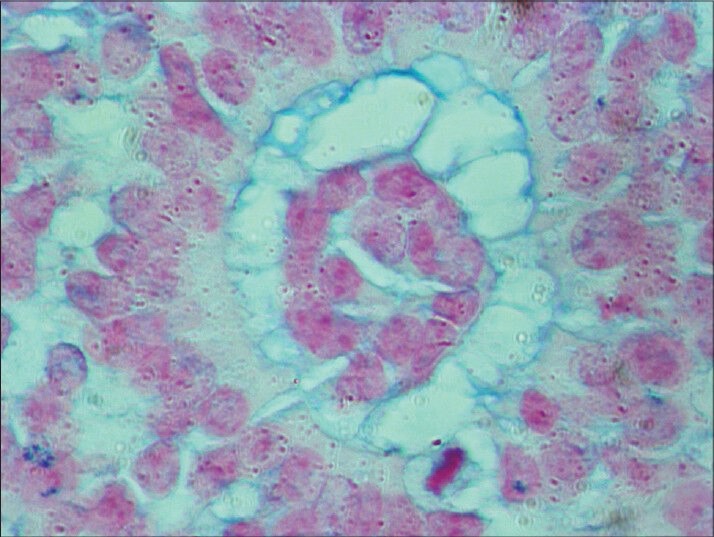

Figure 6.

One of the newly observed rosettes stained with alcian blue (HR-AMP). Lumen was stained (×400). HR-AMP = hyaluronidaseresistant acid mucopolysaccharides

Figure 8.

Necrosis and calcification (H and E, ×200)

Figure 7.

Alcian blue (HR-AMP) stained central lumen of FW rosette in same slide as control (×400)

Discussion

Rosettes are round assemblage of cells found in tumor.[2,3,4,5,6,7] They usually consist of cells in a spoke circle, a halo collection surrounding a central or acellular lumen. Rosettes are so named for their similarity to the rose casement found in gothic cathedrals (beautiful rose porthole in the church of Notre-Dame in Strasbourg).[8]

There are cluster of different kinds of rosettes in pathology, each with different kind of cells and dissimilar names.[2,8] Most of them are found in tumors of the nervous system.[2,8,9] The detection of rosettes help in the diagnosis of different tumors.[2,4,8]

There are three types of true rosettes in pathology namely; 1. HW rosette, 2. FW rosette, and 3. true ependymal rosette.[4,7,8] Perivascular pseudorosette, which is often described in literature as a fourth type is not a true rosette.[8] First two rosettes and pseudorosettes are exclusively found in retinoblastoma.[2,5,8]

HW rosette (named after James Homer Wright, the first director of the Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, USA) is typically seen in neuroblastoma, medulloblastoma, primitive neuroectodermal tumors (PNETs) and retinoblastoma.[8] They lack a central lumen and their constituent cells encompass a central tangle of neural filaments. Their presence indicates neuroblastic differentiation.[2,8,9]

FW rosette (named after pathologist Simon Flexner and ophthalmologist Hugo Wintersteiner) is feature of retinoblastoma.[8] It consists of tumor cells neighboring the central lumen, which is stained with alcian blue (HR-AMP) that contains cytoplasmic extensions from the tumor cells.[2,5,8,9] FW rosettes represent early attempt at retinal differentiation and these rosettes are composed of a ring of cuboidal cells surrounding the central lumen. The lumen corresponds to subretinal space and stains with alcian blue (HR-AMP).[2,5,8,9] The cells surrounding the lumen are joined near the apices by intracellular connections (zonulae adherents), which is analogous to the external limiting membrane of retina.[2,8,9,10] FW rosettes are not pathognomonic because they also occur in malignant medulloepitheliomas and some pineal tumors.[2,4,9] On electron microscopy, they have features of primordial photoreceptor cells. Cilia, which exhibit the 9 + 0 pattern of microtubule doublets found in central nervous system's tumors, project in the lumen. Cilia are hypothesized to be the precursor of photoreceptor outer segments.[2,8,9,10]

Third rosette in pathology is a true ependymal rosette consisting of tumor cells surrounding an empty lumen. It is thought that these structures signify attempts by the tumor cells to remake ventricles with ependymal lining.[8]

A pseudorosette consists of tumor cells collected around a viable blood vessel (perivascular pseudorosette).[8] It is called pseudorosette because the middle structure is not the part of the tumor. These types of rosettes are common in ependymomas, medulloblastoma, PNET, retinoblastoma, etc.[2,8,9]

About 15-20% of retinoblastomas harbor very well-differentiated foci of actual photoreceptor differentiation. Such areas contain aggregates of neoplastic photoreceptors called fleurettes by T'so, Zimmerman, and Fine. Fleurettes are typically found in retinoblastomas on low magnification microscopy of H and E stained sections and are paucicellular compared to adjacent undifferentiated areas of viable tumors that appear relatively eosinophilic.[2,3,9,10] Fleurettes denote bouquet-like, bulbous eosinophilic processes and are cytologically benign cells joined by series of zonulae adherents comprising a short segment of neoplastic external limiting membranes.[2,6,8]

The newly observed rosettes in our retinoblastoma case, in addition to FW and HW rosettes consisted of clear lumens and inside the lumens there were collections of basophilic cells. By and large, this type of new rosette is larger than the FW or HW rosette. Peripheral outer cells were same as FW and HW rosettes. Like the FW rosette, the lumen was stained with alcian blue (HR-AMP). Eosinophilic cytoplasmic extensions were seen inside the lumen connecting the cells as well as outside peripheral cells as in FW rosette.[2,8,9]

In our case, the anterior chamber involvement and minimal necrosis in differentiated retinoblastoma was somewhat unusual to explain. Normally, the mechanisms of tumor regression in retinocytoma are thought to be apoptosis and these regressions are caused by ischemic or immune-mediated necrosis. Our findings were incompatible with the histopathological features of retinocytoma.[2,9,10]

Acknowledgement

Sri Kanchi Sankara Health and Educational Foundation

ICMR.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil.

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

References

- 1.Shields CL, Mashayekhi A, Au AK, Czyc C, Leahey A, Meadow AT, et al. The international classification of retinoblastoma predicts chemoreduction success. Ophthalmology. 2006;113:2276–80. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2006.06.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Eagle RC Jr, editor. Eye pathology - An atlas and text. Philadelphia: Lippincott William and Wilkins; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tsߣo MO, Zimmerman LE, Fine BS. The nature of retinoblastoma. I. Photoreceptor differentiation: A clinical and histopathological study. Am J Ophthalmol. 1970;69:339–49. doi: 10.1016/0002-9394(70)92263-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Eagle RC., Jr High-risk features and tumour differentiation in retinoblastoma: A retrospective histopathologic study. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2009;133:1203–9. doi: 10.5858/133.8.1203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Madhavan J, Ganesh A, Roy J, Biswas J, Kumaramanickavel G. The relationship between tumour cell differentiation and age at diagnosis in retinoblastoma. J Pediatr Ophthalmol Strabismus. 2008;45:22–5. doi: 10.3928/01913913-20080101-16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Margo C, Hidayat A, Kopelman J, Zimmerman LE. Retinocytoma: A benign variant of retinoblastoma. Arch Ophthalmol. 1983;101:1519–31. doi: 10.1001/archopht.1983.01040020521003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Eagle RC, Jr, Shields JA, Donoso L, Milner RS. Malignant transformation of spontaneously regressed retinoblastoma, retinoma/retinocytoma variant. Opthalmology. 1989;96:1389–95. doi: 10.1016/s0161-6420(89)32714-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Girolami UD, Anthony DC, Frosch MP. Central nervous system. In: Cotran RS, Kumar V, Collins T, editors. Robbins Pathologic Basis of Disease. 6th ed. Philadelphia: Elsevier Health Sciences; 2001. pp. 1293–357. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nork TM, Schwartz TL, Doshi HM, Millecchia LL. Retinoblastoma. Cell of origin. Arch Ophthalmol. 1995;113:791–802. doi: 10.1001/archopht.1995.01100060117046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Biswas J, Das D, Krishnakumar S, Shanmugan MP. Histopathologic analysis of 232 eyes with retinoblastoma conducted in an Indian tertiary- care ophthalmic center. J Pediatr Ophthalmol Strabismus. 2003;40:265–7. doi: 10.3928/0191-3913-20030901-05. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]