Abstract

Background:

The female athlete triad is the interrelatedness of energy availability, menstrual function, and bone density. Currently, limited information about triad components and their relationship to musculoskeletal injury in the high school population exists. In addition, no study has specifically examined triad components and injury rate in high school oral contraceptive pill (OCP) users.

Hypothesis:

To compare the prevalence of disordered eating (DE), menstrual irregularity (MI), and musculoskeletal injury (INJ) among high school female athletes in OCP users and non-OCP users.

Study Design:

Retrospective cohort study.

Level of Evidence:

Level 2.

Methods:

The subject sample completed the Eating Disorder Examination-Questionnaire (EDE-Q) and Healthy Wisconsin High School Female Athletes Survey (HWHSFAS). Athletes were classified by OCP use and sport type.

Results:

Of the participants, 14.8% reported OCP use. There was no difference in MI and INJ among groups. The prevalence of DE was significantly higher among OCP users as compared with non-OCP users; OCP users were twice as likely to meet the criteria for DE (odds ratio [OR], 2.47; 95% confidence interval [CI], 1.20-5.09). OCP users were over 5 times more likely to have a global score that met criteria for DE as compared with non-OCP users (OR, 5.36; 95% CI, 1.92-14.89).

Conclusion:

Although MI and INJ rates are similar among groups, there is a higher prevalence of DE among high school female athletes using OCPs as compared with non-OCP users.

Clinical Relevance:

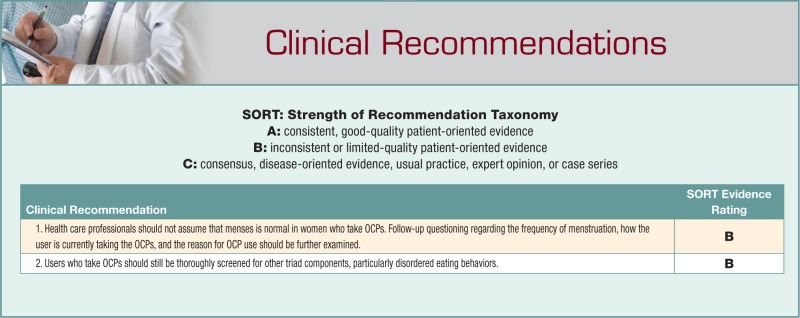

Because OCP users may be menstruating, clinicians may fail to recognize the other triad components. However, DE exists in the menstruating OCP user. As such, clinicians should be vigilant when screening for triad components in high school OCP users, particularly DE.

Keywords: female athlete triad, musculoskeletal disorder, sports

Since the implementation of Title IX in 1972, which required equal programming for boys and girls in any school receiving federal financial assistance, girls’ participation in high school–sponsored sports has increased by 34%.2 Numerous benefits to female sports participation have been observed, including an increased high school graduation rate, improved self-esteem, and a more positive body image as compared with nonathletes, with the benefits of exercise far outweighing the risks.47 However, in 1992, the American College of Sports Medicine (ACSM) identified an association of disordered eating, amenorrhea, and osteoporosis in athletes participating in sporting activities that emphasize a lean physique. This condition was recognized as the “female athlete triad,” and the ACSM first published a position statement on the condition in 1997.50 Based on updated scientific evidence and discoveries, the statement was subsequently revised in 2007,47 with the updated version changing the term disordered eating to energy availability, which is defined as energy intake minus energy expenditure, or the amount of energy remaining after exercising for the regulation of normal bodily functions.47,59,62 Intentional caloric restriction that causes low energy availability often manifests as disordered eating (DE).6,7,47,59,62 Currently, studies reporting the prevalence of DE or low energy availability among high school athletes are limited, and the prevalence ranges from 18.2% to 36.5%.28,48,49,52,58,61

According to the updated position statement, “menstrual function” refers to a spectrum ranging from eumenorrhea, or normal menses, to amenorrhea.47 Menstrual dysfunction is often referred to as menstrual irregularity (MI) and includes primary amenorrhea, secondary amenorrhea, and oligomenorrhea.47 A higher prevalence of MI has been reported in the athletic population compared with the general population.5,28,47,64 Studies in the adolescent athletic population have estimated the prevalence of MI to range from 16.6% to 54%, suggesting that MI may be a medical problem among high school athletes.28,48,49,61 However, oral contraceptive pill (OCP) use was not specifically assessed in these previous studies.

According to the 2007 position statement, bone mineral density (BMD) in female patients spans a spectrum from optimal bone health to osteoporosis.47,50 In adolescents, low bone mass is defined as “bone mineral density lower than expected for age-matched norms.”30,31,47 Because approximately 50% of peak bone mass is accrued during adolescence,38 it is a critical time for optimizing nutrition, especially dietary intake of calcium and vitamin D. Studies related to low bone mass in the female adolescent population are limited, with the prevalence of low bone mass in female adolescents ranging from 13.0% to 21.8%.3,28,49

Nearly 12 million women in the United States use OCPs.14 OCP use is highest in women under the age of 30 years, which is a critical time for bone mass accrual. The effect of OCP use on bone remains unclear, with increasing evidence suggesting current OCP formulations may act differently in women who have not yet achieved peak bone mass as compared with skeletally mature women.27,40,53,56 From 2006 to 2008, there were nearly 1.6 million teens aged 15 to 19 years using OCPs for contraception.45 Teens also take oral contraceptives for noncontraceptive reasons, including treatment of menstrual cramps, premenstrual syndrome, polycystic ovary syndrome, and for the timing and regulation of menstruation.

At present, there are no studies that have examined the effect of OCP use on DE and menstrual irregularity. In addition, no studies have investigated whether OCP use is a risk factor for musculoskeletal injury. The purpose of this study was to determine the prevalence of DE, MI, and musculoskeletal injury (INJ; other than stress fractures) in the high school population in OCP users and non-OCP users.

Materials and Methods

Subjects

During the 2006-2007 school year, 3 local high schools in the greater Madison, Wisconsin, area were selected by convenience to participate in the study. There were 850 female athletes who participated in a school-sponsored sport, dance team, cheerleading, and pom squad who remained on the roster throughout the entire season and were eligible for study participation. Of 850 possible questionnaires that could be completed, 334 (response rate, 39.3%) were collected. Multisport athletes (n = 23) were individuals who participated in the study twice; they were only included once in the data analysis and were designated according to the first sport in which they participated for the school year. In addition, athletes (n = 6) who did not answer the question related to OCP use were eliminated from the data set. Lastly, girls who had not reached menarche (n = 14) at the time of the survey were excluded. Therefore, our final sample size for analysis was 291 athletes. Athletes were grouped into a 3-sport classification system as described by Beals and Manore (Table 1).8 Esthetic activities were sports that had a subjective scoring component; endurance sports included sports where intense exercise lasted beyond several minutes whereby aerobic metabolism is the primary energy system41; lastly, team/anaerobic (T/A) sports were those in which the short-term energy system required maximal exercise for up to 3 minutes and where the primary energy source was almost exclusively adenosine triphosphate (ATP) and phosphocreatine (PCr).41 There were no athletes excluded due to an inability to understand written and spoken English. Written parental consent and subject assent were obtained prior to study participation. The study was approved by the Institutional Review Boards at the University of Wisconsin-Madison and Rocky Mountain University of Health Professions.

Table 1.

Classification of sports

| Sport Classification | Sports |

|---|---|

| Esthetic sports | Cheerleading, pom squad, dance team, diving, and gymnastics |

| Endurance sports | Basketball, cross-country, soccer, and track (middle distance and distance running events) |

| Team/anaerobic sports | Tennis, volleyball, swimming, softball, golf, and track (field events and sprints) |

Data Collection

Subject data were collected at the end of the respective activity season. Each athlete completed a questionnaire about eating attitudes and behaviors and a questionnaire that inquired about their menstrual status, recent and past injury history, and other demographic information (age, height, weight, and ethnic origin) in a group format with teammates. Prior to completing the questionnaires, general instructions were given to the group. Subjects were then instructed to sit far apart from one another. Because multiple research assistants were used, assistants were trained in a standardized written procedure to ensure consistency in the data collection process.

Eating Attitudes and Behaviors

Each subject completed the Eating Disorder Examination-Questionnaire (EDE-Q) to identify eating attitudes and behaviors.11,20 The EDE-Q has high internal consistency and moderate to high concurrent and criterion validity.9,12,20,39,44 The EDE-Q can be completed in approximately 15 minutes and correlates highly with the Eating Disorders Examination (EDE), which is a one-on-one interview by a trained professional.12,25,26,39,43,44,57,60 The EDE-Q was given to the athletes with verbal instruction because it is more highly correlated with the EDE when verbal instructions are provided.13,23,51 The EDE-Q reflects eating behaviors over the previous 28 days. Of the 28 questions, 22 can be categorized into 4 different subscales (weight concern, shape concern, eating concern, and dietary restraint), generating a score for each subscale and a global score (composite mean score of the 4 subscales). The other 6 questions assess pathogenic eating behaviors, such as binge eating, self-induced vomiting, laxative use, and use of diuretics or diet pills to control body weight. Subjects were classified as having DE if they had a mean score of ≥4.0 on the dietary restraint, weight concern, or shape concern subscales; had a mean global score of ≥4.0 on the EDE-Q; or reported performing 2 or more of the listed pathogenic eating behaviors more than 1 time in the past 28 days.48,49 The cut-off score of ≥4.0 on the subscales or the mean of the subscales indicates that a specific attitude or behavior was reported on more than half of the past 28 days and was used to define DE because it has been shown to be predictive of eating disorders.12 Based on this scoring rubric, athletes were divided into 2 groups: athletes with DE (mean score of ≥4.0 on the dietary restraint, weight concern, or shape concern subscales; having a mean global score of ≥4.0; or having a pathologic behavior) or athletes with normal eating attitudes and behaviors.48,49

Menstrual Status

Each subject completed the Healthy Wisconsin High School Female Athlete Survey (HWHSFAS). The questionnaire was developed by our research team and inquired about the subject’s menstrual status over the past 12 months (frequency and duration of menstrual cycles), age at menarche, OCP use, and length of OCP use. The questionnaire took approximately 5 minutes to complete. A pilot study was conducted to assess the test/retest reliability of the menstrual history questions of the HWHSFAS on a convenience sample of 11 high school athletes who completed the form twice, 8 days apart. The intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC3,1) values for questions on age at menarche and number of periods during the past year were 0.95 and 0.99, respectively; the kappa value for OCP use was 1.0. Menstrual irregularity was defined as having 9 or fewer menstrual cycles in the past 12 months, which identifies all patients suffering from secondary amenorrhea or oligomenorrhea.47 Subjects were then classified into 1 of 2 menstrual status groups: athletes with MI (having 9 or fewer menstrual cycles in the past 12 months) or athletes with normal menses.

Musculoskeletal Injury

At the end of each sports season, subjects were asked to report their self-perceived injuries during the current sports season. The injuries did not have to be reported to a coach or athletic trainer to be included in the study analyses. The questionnaire also inquired about any history of injuries during previous seasons playing the current sport. Musculoskeletal injury was defined as an injury either from direct trauma or overuse that was the direct result of participation in sport during the season. For each injury, subjects reported if the injury occurred traumatically or was overuse related. Overuse injury was defined on the questionnaire as a condition “where the pain came on gradually and was not due to a fall, running into another athlete, slipping, or twisting the body.” Traumatic injury was defined for the subjects on the questionnaire as “an injury caused by running into another player, tripping, or falling.” Examples of both injury types were provided on the questionnaire next to the specific body part. Athletes also reported the body part injured and the time lost from practice or competition. Our study injury definition included injuries that did not cause the athlete to miss any participation time.4

When the athlete returned her questionnaire, the questionnaire was reviewed to identify unanswered questions. Clarification of any unanswered question(s) was offered, and the athlete was provided with an opportunity to answer the question(s).

Data Analysis

Subject characteristics were described with means and standard deviations, median and range, or frequency and percentages when appropriate. Comparisons in subject characteristics between those using OCPs and those that were not were made by using the t test for continuous variables or the Fisher exact test for categorical variables.

Analysis of DE and EDE-Q subscales between the 2 groups were done both univariately with the Fisher exact test and multivariately with a logistic regression that controlled for age and sport type. Statistical significance was preset to alpha <0.05 for all tests. All study analyses were conducted using R statistical software (version 2.12.1; Vienna, Austria).

Results

Of the 291 study participants, 43 (14.8%) reported OCP use, and 248 (85.2%) reported not using OCPs (Table 2). Athletes reporting OCP use were significantly older than non-OCP users (P < 0.00). There were no differences between age at menarche, height, weight, or body mass index (BMI) between groups.

Table 2.

Characteristics of study participants (mean ± SD)

| Characteristic | OCP Users (n = 43) | Non-OCP Users (n = 248) | P Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Current age, y | 16.4 ± 1.1 | 15.3 ± 1.1 | <0.00a |

| Grade in school, n (%) | <0.00b | ||

| 9 | 5 (11.6%) | 94 (37.9%) | |

| 10 | 8 (18.6%) | 78 (31.5%) | |

| 11 | 10 (23.3%) | 45 (18.1%) | |

| 12 | 20 (46.5%) | 31 (12.5%) | |

| Age at menarche, y | 12.3 ± 1.1 | 12.4 ± 1.1 | 0.57a |

| Height, m | 1.66 ± 0.07 | 1.67 ± 0.07 | 0.78a |

| Weight, kg | 60.6 ± 9.3 | 58.7 ± 9.4 | 0.22a |

| BMI, kg/m2 | 21.9 ± 3.0 | 21.1 ± 2.9 | 0.12a |

| Median months on OCP (range) | 6 (1-48) |

OCP, oral contraceptive pill; BMI, body mass index.

t test.

Fisher exact test.

When compared with the distribution of sports in non-OCP users, a significantly higher proportion of OCP users were esthetic athletes and a significantly lower proportion of OCP users were found in endurance sports (P < 0.001) (Table 3). The proportion of anaerobic athletes in each group was fairly consistent. There were no differences between groups regarding MI or INJ (Table 4).

Table 3.

Percentage of OCP users and non-OCP users by sport type

| OCP Users (n = 43) | Non-OCP Users (n = 248) | P Valuea | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sport class type | <0.00 | ||

| Esthetic sports | 14 (32.6%) | 23 (9.3%) | |

| Endurance sports | 4 (9.3%) | 70 (28.2%) | |

| Team/anaerobic sports | 25 (58.1%) | 155 (62.5%) |

OCP, oral contraceptive pill.

Fisher exact test.

Table 4.

Prevalence of MI and INJ in OCP users and non-OCP users

| OCP Users (n = 43) | Non-OCP Users (n = 248) | P Valuea | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Menstrual irregularity | 6 (14.0%) | 48 (19.4%) | 0.405 |

| Overall injury | 30 (69.8%) | 157 (63.3%) | 0.492 |

| Overuse injury | 30 (100%) | 140 (89.2%) | 0.079 |

| Traumatic injury | 10 (33.3%) | 67 (42.7%) | 0.420 |

MI, menstrual irregularity (9 or fewer menstrual cycles in the past 12 months); INJ, musculoskeletal injury; traumatic injury, injury caused by running into another player, tripping, or falling; OCP, oral contraceptive pill; overuse injury, injury where the pain came on gradually and was not due to a fall, running into another athlete, slipping, or twisting the body.

Fisher exact test.

The prevalence of DE was significantly higher in OCP users as compared with non-OCP users (P = 0.01) (Table 5). In addition, the prevalence of the EDE-Q subscales and global score was significantly higher in OCP users as compared with non-OCP users for all subscales (all P < 0.05).

Table 5.

Univariate analysis of DE prevalence among OCP users and non-OCP users

| Measurement | OCP Users (n = 43) | Non-OCP Users (n = 248) | P Valuea |

|---|---|---|---|

| DE | 24 (55.8%) | 81 (32.7%) | 0.01 |

| EDE-Q subscales | |||

| Dietary restraint (≥4) | 10 (23.3%) | 14 (5.6%) | 0.00 |

| Weight concern (≥4) | 16 (37.2%) | 33 (13.3%) | 0.00 |

| Shape concern (≥4) | 17 (39.5%) | 40 (16.1%) | 0.00 |

| Global score (≥4) | 10 (23.3%) | 16 (6.5%) | 0.00 |

EDE-Q, Eating Disorder Examination-Questionnaire; DE, disordered eating (reported performing ≥2 of the listed pathogenic eating behaviors on the EDE-Q ≥2 times in the past 28 days); OCP, oral contraceptive pill; EDE-Q subscale scoring, disordered eating defined as having a score ≥4.0 on the dietary restraint, weight concern, or shape concern subscales; global score on the EDE-Q, disordered eating defined as having a mean global score (an average of the subscales) of ≥4.0 on the EDE-Q.

Fisher exact test.

OCP users are over 2 times more likely to have DE compared with non-OCP users (OR, 2.47; 95% CI, 1.20-5.09) (Table 6). In addition, OCP users were over 5 times more likely to meet the EDE-Q subscale criteria for dietary restraint (OR, 5.19; 95% CI, 1.88-14.31) and over 3 times more likely to meet EDE-Q subscale criteria for weight concern (OR, 3.52; 95% CI, 1.57-7.88) and shape concern (OR, 3.20; 95% CI, 1.46-6.99). Lastly, OCP users were over 5 times more likely to meet EDE-Q global score criteria (OR, 5.36; 95% CI, 1.92-14.98).

Table 6.

Adjusted odds ratios for DE behaviors for OCP users when controlling for age and sport type

| Measurement | Odds Ratio (95% CI) | P Valuea |

|---|---|---|

| Disordered eating | 2.47 (1.20-5.09) | 0.01 |

| EDE-Q subscales | ||

| Dietary restraint (≥4) | 5.19 (1.88-14.31) | 0.00 |

| Weight concern (≥4) | 3.52 (1.57-7.88) | 0.00 |

| Shape concern (≥4) | 3.20 (1.46-6.99) | 0.00 |

| Global score (≥4) | 5.36 (1.92-14.98) | 0.00 |

EDE-Q, Eating Disorder Examination-Questionnaire; DE, disordered eating (reported performing ≥2 of the listed pathogenic eating behaviors on the EDE-Q ≥2 times in the past 28 days); OCP, oral contraceptive pill; EDE-Q subscale scoring, disordered eating defined as having a score ≥4.0 on the dietary restraint, weight concern, or shape concern subscales; global score on the EDE-Q, disordered eating defined as having a mean global score (an average of the subscales) of ≥4.0 on the EDE-Q.

Fisher exact test.

Discussion

There were no differences in the prevalence of MI and musculoskeletal injury between groups. However, the prevalence of disordered eating, including all EDE-Q subscales and the EDE-Q global score, was significantly higher in OCP users as compared with non-OCP users.

Menstrual Irregularity

Of the few studies that have reported the prevalence of MI in high school athletes, the findings range from 18.9% to 54%.28,48,49,61 Although athletes were surveyed about OCP use in these studies,28,48,49,61 they were not excluded from data analysis. In the present study, 14.0% of OCP users reported MI, whereas 19.4% of non-OCP users reported MI. Although there was no difference between groups, these findings are somewhat contradictory; OCP users should have regular menses. In the present study, MI was defined as having 9 or fewer menstrual cycles in the past 12 months, which identifies all patients suffering from secondary amenorrhea or oligomenorrhea.47 Secondary amenorrhea is a cessation of menstruation for 3 consecutive months in the adolescent who has started menstruating, while oligomenorrhea is defined as menstrual cycles occurring greater than 35 days apart.47 Of the 43 OCP users, 18 reported using OCPs for ≤5 months, 11 reported taking OCPs for 6 to 10 months, while 14 reported taking OCPs for ≥11 months. As such, almost half (43%) of OCP users had been taking the medication for <6 months. Because we did not ask specific questions about how the menstrual cycle had changed over the past 12 months (ie, become more regular or more irregular, shortened or lengthened) we cannot conclude if there is an association between length of time using OCPs and regulation of menstruation in this group. The prevalence of MI in the non-OCP user group was 14.0%, which is slightly lower than findings from previous studies that determined the prevalence of MI regardless of OCP use.27,48,49,61 One potential reason for this difference may be due to the definition of MI used in the present study. We did not include subjects with primary amenorrhea, whereas previous studies included this in their definition of MI.27,48,49,61 Primary amenorrhea is the lack of menstruation by age 15 years.15,24,59 Athletes with primary amenorrhea were excluded from our study because we wanted to determine the prevalence of OCP use in girls who had reached menarche. Previous studies have reported the prevalence of primary amenorrhea in high school athletes to range from 0.8% to 1.2%.49,61 As such, the study definition may contribute to the slightly lower prevalence of MI observed in our study.

Normal menstruation is important in the female adolescent. Estrogen has a significant influence on bone development; higher estrogen levels positively affect calcium levels, leading to elevated calcium storage within bone.18 Because approximately 50% of peak bone mass is accrued during adolescence,38 the more time spent without adequate estrogen levels (as seen with oligomenorrhea and amenorrhea) during growth leads to a lower peak bone mass, ultimately leading to a lower lifetime bone density.18,46

Musculoskeletal Injury

The cumulative seasonal prevalence of musculoskeletal injury in OCP users and non-OCP users was 69.8% and 63.3%, respectively, with no difference between groups. Therefore, according to our study, there is no relationship between OCP use and injury rate. Our prevalence findings for both groups are higher than those of previous studies of high school female athletes.21,32,54,55 This difference may be due to the definition of injury used in this study. Numerous previous studies have required the athlete to miss sport participation to fit their criteria for “injury.”21,22,32,54,55 However, an 8-year longitudinal injury surveillance study of high school sports that used an injury definition that did not require the athlete to miss any practice or competition reported an overall injury incidence of 46% for female athletes.4 Our injury estimate may be higher because of methodological differences. We included all injuries regardless of whether they were reported to the licensed athletic trainer (LAT), whereas Beachy et al4 included only those reported to the LAT. In addition, Beachy et al4 collected injury data for 9 years, whereas our study only looked at 1 sport season. Lastly, we sampled different sports in our study, which will ultimately affect injury incidence.4

Disordered Eating

DE may involve behaviors such as restrictive eating (eating less or avoiding or minimizing certain “bad” foods), fasting, skipping meals, or use of diet pills, laxatives, diuretics, enemas, or binge eating followed by purging (vomiting).6,7,47,59,62 Presently, reports on the prevalence of DE among high school athletes are limited.48,49,61 Utilizing the EDE-Q in 2 separate reports, Nichols et al48,49 determined DE prevalence to be 18.2% and 20.0%, respectively. In a study using the EDE-Q and similar criterion, the prevalence of DE was 34.7%.61 A possible explanation for the different prevalence estimates may be due to the sports included in these studies. Nichols et al48,49 did not include esthetic sports in their studies, whereas Thein-Nissenbaum et al61 included esthetic sports, which comprised over 12% of their sample population. Using the same criteria as the previous studies,48,49,61 the present study determined the prevalence of DE for OCP and non-OCP users to be 55.8% and 32.7%, respectively. The DE prevalence for non-OCP users is similar to a previous study;61 however, the prevalence of DE among OCP users is alarmingly high, with over 50% of OCP users meeting criteria for disordered eating. In addition, the prevalence of all EDE-Q subscales and the global EDE-Q score were all significantly higher in OCP users as compared with non-OCP users. One possible explanation for these findings is the composition of the groups: There were significantly more esthetic athletes in the OCP group as compared with the non-OCP group. This theory is supported by previous research.61

In this study, OCP users were over 2 times more likely to meet the criteria for DE. DE behaviors may result in low energy availability for bodily functions after exercise training.47,59,62 The reproductive system undergoes changes due to a decrease in acute energy available. This theory has been supported by findings reported by Loucks et al,37 who examined the alterations in reproductive function in exercising women by assaying blood samples during menstrual cycles while controlling the intensity of exercise and caloric intake. Reproductive function was not disrupted by exercise stress but was affected by low energy availability. In a subsequent study, Loucks35 determined that reproductive disruption may occur when negative energy balance falls below a specific threshold of 20 to 30 kcal/kgLBM/d. In a similar study by De Souza et al,16 49 female patients were grouped according to exercise status (exercising vs sedentary) and menstrual status (menstrual disturbance vs normal ovulation). All groups with menstrual disturbances had a significantly lower resting energy expenditure compared with groups with normal ovulation. They also noted that as the magnitude of negative energy balance increases, the alterations in the reproductive system become more severe.16 Based on these studies,16,19,34-37,63 it appears that alterations in reproductive function are related to acute energy availability. Disordered eating behaviors, with resultant decreased energy availability, have been related to changes in the menstrual cycle, such as increased time between cycles (oligomenorrhea) or cessation of menstruation (secondary amenorrhea).1,10,17,24,29,33,42,48,49

Limitations

Study participants were not asked their reasons for OCP use. Teens may take OCPs to regulate irregular menstrual cycles for comfort and convenience. Another limitation is related to how the OCPs were prescribed or taken. Continuous cycling, where the user continuously takes OCPs and skips the week of placebo pills, which causes withdrawal bleeding, can be purposeful and intentional. Some OCPs are marketed such that the user only menstruates 2 to 4 times per year. As such, these users may appear to have MI when actually the frequency at which they menstruate is a personal choice.

Conclusion

There was no difference in prevalence of MI or musculoskeletal injury rate between OCP users and nonusers. However, the prevalence of DE was significantly higher among pill users; pill users were over 2 times more likely to meet the criteria for DE.

Footnotes

The following author declared potential conflicts of interest: Jill M. Thein-Nissenbaum, PT, DSc, SCS, ATC, received the National Athletic Trainer’s Association Doctoral Grant.

References

- 1. Ackard DM, Peterson CB. Association between puberty and disordered eating, body image, and other psychological variables. Int J Eat Disord. 2001;29:187-194 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Associations NFoSHS. Interacative participation survey results. http://www.nfhs.org/content.aspx?id=3282&linkidentifier=id&itemid=3282 Accessed August 13, 2010

- 3. Barrack MT, Rauh MJ, Barkai HS, Nichols JF. Dietary restraint and low bone mass in female adolescent endurance runners. Am J Clin Nutr. 2008;87:36-43 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Beachy G, Akau CK, Martinson M, Olderr TF. High school sports injuries. A longitudinal study at Punahou School: 1988 to 1996. Am J Sports Med. 1997;25:675-681 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Beals KA. Eating behaviors, nutritional status, and menstrual function in elite female adolescent volleyball players. J Am Diet Assoc. 2002;102:1293-1296 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Beals KA. Eating disorder and mentsrual dysfunction screening, education, and treatment programs. Phys Sportsmed. 2003;31:33-38 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Beals KA, Hill AK. The prevalence of disordered eating, menstrual dysfunction, and low bone mineral density among US collegiate athletes. Int J Sport Nutr Exerc Metab. 2006;16:1-23 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Beals KA, Manore MM. Disorders of the female athlete triad among collegiate athletes. Int J Sport Nutr Exerc Metab. 2002;12:281-293 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Binford RB, Le Grange D, Jellar CC. Eating disorders examination versus Eating Disorders Examination-Questionnaire in adolescents with full and partial-syndrome bulimia nervosa and anorexia nervosa. Int J Eat Disord. 2005;37:44-49 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Byrne S, McLean N. Eating disorders in athletes: a review of the literature. J Sci Med Sport. 2001;4:145-159 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Carter JC, Aimé AA, Mills JS. Assessment of bulimia nervosa: a comparison of interview and self-report questionnaire methods. Int J Eat Disord. 2001;30:187-192 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Carter JC, Stewart DA, Fairburn CG. Eating disorder examination questionnaire: norms for young adolescent girls. Behav Res Ther. 2001;39:625-632 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Celio AA, Wilfley DE, Crow SJ, Mitchell J, Walsh BT. A comparison of the binge eating scale, questionnaire for eating and weight patterns-revised, and eating disorder examination questionnaire with instructions with the eating disorder examination in the assessment of binge eating disorder and its symptoms. Int J Eat Disord. 2004;36:434-444 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Chandra A, Martinez GM, Mosher WD, Abma JC, Jones J. Fertility, family planning, and reproductive health of U.S. women: data from the 2002 National Survey of Family Growth. Vital Health Stat 23. 2005;(25):1-160 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Cobb KL, Bachrach LK, Greendale G, et al. Disordered eating, menstrual irregularity, and bone mineral density in female runners. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2003;35:711-719 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. De Souza MJ, Lee DK, VanHeest JL, Scheid JL, West SL, Williams NI. Severity of energy-related menstrual disturbances increases in proportion to indices of energy conservation in exercising women. Fertil Steril. 2007;88:971-975 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. DePalma MT, Koszewski WM, Romani W, Case JG, Zuiderhof NJ, McCoy PM. Identifying college athletes at risk for pathogenic eating. Br J Sports Med. 2002;36:45-50 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Drinkwater BL, Nilson K, Ott S, Chesnut CH., III Bone mineral density after resumption of menses in amenorrheic athletes. JAMA. 1986;256:380-382 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Eliakim A, Beyth Y. Exercise training, menstrual irregularities and bone development in children and adolescents. J Pediatr Adolesc Gynecol. 2003;16:201-206 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Fairburn CG, Beglin SJ. Assessment of eating disorders: interview or self-report questionnaire? Int J Eat Disord. 1994;16:363-370 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Fernandez WG, Yard EE, Comstock RD. Epidemiology of lower extremity injuries among U.S. high school athletes. Acad Emerg Med. 2007;14:641-645 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Garrick JG, Requa RK. Injuries in high school sports. Pediatrics. 1978;61:465-469 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Goldfein JA, Devlin MJ, Kamenetz C. Eating Disorder Examination-Questionnaire with and without instruction to assess binge eating in patients with binge eating disorder. Int J Eat Disord. 2005;37:107-111 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Greydanus DE, Patel DR. The female athlete. Before and beyond puberty. Pediatr Clin North Am. 2002;49:553-580, vi. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Grilo CM, Masheb RM, Wilson GT. A comparison of different methods for assessing the features of eating disorders in patients with binge eating disorder. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2001;69:317-322 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Grilo CM, Masheb RM, Wilson GT. Different methods for assessing the features of eating disorders in patients with binge eating disorder: a replication. Obes Res. 2001;9:418-422 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Hartard M, Kleinmond C, Wiseman M, Weissenbacher ER, Felsenberg D, Erben RG. Detrimental effect of oral contraceptives on parameters of bone mass and geometry in a cohort of 248 young women. Bone. 2007;40:444-450 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Hoch AZ, Pajewski NM, Moraski L, et al. Prevalence of the female athlete triad in high school athletes and sedentary students. Clin J Sport Med. 2009;19:421-428 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Ilardi D. Helping teenage girls avoid the female athlete triad. School Nurse News. 2002;19(4):34-38 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. International Society for Clinical Densitometry. Official position of the International Society for Clinical Densitometry. http://www.iscd.org/official-positions/1st-iscd-pediatric-position-development-conference/ Published 2005. Accessed February 13, 2013

- 31. Khan KM, Liu-Ambrose T, Sran MM, Ashe MC, Donaldson MG, Wark JD. New criteria for female athlete triad syndrome? As osteoporosis is rare, should osteopenia be among the criteria for defining the female athlete triad syndrome? Br J Sports Med. 2002;36:10-13 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Knowles SB, Marshall SW, Bowling JM, et al. A prospective study of injury incidence among North Carolina high school athletes. Am J Epidemiol. 2006;164:1209-1221 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Kotler LA, Cohen P, Davies M, Pine DS, Walsh BT. Longitudinal relationships between childhood, adolescent, and adult eating disorders. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2001;40:1434-1440 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Loucks AB. Effects of exercise training on the menstrual cycle: existence and mechanisms. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 1990;22:275-280 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Loucks AB. Energy availability, not body fatness, regulates reproductive function in women. Exerc Sport Sci Rev. 2003;31:144-148 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Loucks AB. Introduction to menstrual disturbances in athletes. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2003;35:1551-1552 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Loucks AB, Verdun M, Heath EM. Low energy availability, not stress of exercise, alters LH pulsatility in exercising women. J Appl Physiol. 1998;84:37-46 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Loud KJ, Gordon CM. Adolescent bone health. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2006;160:1026-1032 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Luce KH, Crowther JH. The reliability of the Eating Disorder Examination-Self-Report Questionnaire Version (EDE-Q). Int J Eat Disord. 1999;25:349-351 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Martins SL, Curtis KM, Glasier AF. Combined hormonal contraception and bone health: a systematic review. Contraception. 2006;73:445-469 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. McArdle WD, Katch FI, Katch VL. Exercise Physiology: Energy, Nutrition and Human Performance. Baltimore, MD: Lippincott, Williams, and Wilkins; 2001 [Google Scholar]

- 42. McLean JA, Barr SI. Cognitive dietary restraint is associated with eating behaviors, lifestyle practices, personality characteristics and menstrual irregularity in college women. Appetite. 2003;40:185-192 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Mond JM, Hay PJ, Rodgers B, Owen C, Beumont PJ. Temporal stability of the Eating Disorder Examination Questionnaire. Int J Eat Disord. 2004;36:195-203 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Mond JM, Hay PJ, Rodgers B, Owen C, Beumont PJ. Validity of the Eating Disorder Examination Questionnaire (EDE-Q) in screening for eating disorders in community samples. Behav Res Ther. 2004;42:551-567 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Mosher WD, Jones J. Use of contraception in the United States: 1982-2008. Vital Health Stat 23. 2010;29:1-44 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Myburgh KH, Hutchins J, Fataar AB, Hough SF, Noakes TD. Low bone density is an etiologic factor for stress fractures in athletes. Ann Intern Med. 1990;113:754-759 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Nattiv A, Loucks AB, Manore MM, Sanborn CF, Sundgot-Borgen J, Warren MP. American College of Sports Medicine position stand. The female athlete triad. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2007;39:1867-1882 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Nichols JF, Rauh MJ, Barrack MT, Barkai HS, Pernick Y. Disordered eating and menstrual irregularity in high school athletes in lean-build and nonlean-build sports. Int J Sport Nutr Exerc Metab. 2007;17:364-377 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Nichols JF, Rauh MJ, Lawson MJ, Ji M, Barkai HS. Prevalence of the female athlete triad syndrome among high school athletes. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2006;160:137-142 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Otis CL, Drinkwater B, Johnson M, Loucks A, Wilmore J. American College of Sports Medicine position stand. The female athlete triad. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 1997;29:i-ix [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Passi VA, Bryson SW, Lock J. Assessment of eating disorders in adolescents with anorexia nervosa: self-report questionnaire versus interview. Int J Eat Disord. 2003;33:45-54 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Pernick Y, Nichols JF, Rauh MJ, et al. Disordered eating among a multi-racial/ethnic sample of female high-school athletes. J Adolesc Health. 2006;38:689-695 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Polatti F, Perotti F, Filippa N, Gallina D, Nappi RE. Bone mass and long-term monophasic oral contraceptive treatment in young women. Contraception. 1995;51:221-224 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Powell JW, Barber-Foss KD. Injury patterns in selected high school sports: a review of the 1995-1997 seasons. J Athl Train. 1999;34:277-284 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Rauh MJ, Macera CA, Ji M, Wiksten DL. Subsequent injury patterns in girls’ high school sports. J Athl Train. 2007;42:486-494 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Register TC, Jayo MJ, Jerome CP. Oral contraceptive treatment inhibits the normal acquisition of bone mineral in skeletally immature young adult female monkeys. Osteoporos Int. 1997;7:348-353 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Rizvi SL, Peterson CB, Crow SJ, Agras WS. Test-retest reliability of the eating disorder examination. Int J Eat Disord. 2000;28:311-316 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Rosendahl J, Bormann B, Aschenbrenner K, Aschenbrenner F, Strauss B. Dieting and disordered eating in German high school athletes and non-athletes. Scand J Med Sci Sports. 2009;19:731-739 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Rumball JS, Lebrun CM. Preparticipation physical examination: selected issues for the female athlete. Clin J Sport Med. 2004;14:153-160 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Sysko R, Walsh BT, Fairburn CG. Eating Disorder Examination-Questionnaire as a measure of change in patients with bulimia nervosa. Int J Eat Disord. 2005;37:100-106 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Thein-Nissenbaum JM, Rauh MJ, Carr KE, Loud KJ, McGuine TA. Associations between disordered eating, menstrual dysfunction, and musculoskeletal injury among high school athletes. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 2011;41(2):60-69 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Waldrop J. Early identification and interventions for female athlete triad. J Pediatr Health Care. 2005;19:213-220 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Warren MP, Brooks-Gunn J, Fox RP, et al. Persistent osteopenia in ballet dancers with amenorrhea and delayed menarche despite hormone therapy: a longitudinal study. Fertil Steril. 2003;80:398-404 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Wiksten-Almströmer M, Hirschberg AL, Hagenfeldt K. Menstrual disorders and associated factors among adolescent girls visiting a youth clinic. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2007;86:65-72 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]