Abstract

Objectives

We sought to determine whether circadian patterns in ventricular arrhythmias occur in a current primary prevention defibrillator (ICD) population.

Background

Cardiovascular events, including ventricular arrhythmias, demonstrate biorhythmic periodicity.

Methods

We tested for deviation from the previously described occurrences of a morning peak, early morning nadir and Monday peak in ICD therapies using generalized estimating equations and t-tests. All hypothesis tests were carried out in the entire cohort of patients with ventricular arrhythmias as well as prespecified subgroups.

Results

Of 811 ICD patients, 186 subjects received 714 ICD therapy episodes for life-threatening VA. There was no morning (6 a.m. to 12 noon) peak in therapies for the entire cohort nor in any subgroups. The overall cohort, and several subgroups had a typical early morning (12 midnight to 6 a.m.) nadir in therapies, with significantly less than 25% of therapies occurring during this 6-hour block (all p<0.05). A significant Monday peak in therapies occurred only in patients not on beta blocker (22% of events for the week, p=0.029).

Conclusions

In the SCD-HeFT population, the distribution of life threatening VA failed to demonstrate a typical early morning peak or increased VA events on Mondays. A typical early a.m. nadir was seen in the entire cohort. An increased rate of events on Mondays in the subgroup of subjects not on beta-blockade was found. These findings may indicate suppression of the neurohormonal triggers for ventricular arrhythmia by current heart failure therapy, particularly the use of beta-blockers in heart failure.

Keywords: Circadian, septadian, implantable cardioverter defibrillator, ventricular arrhythmia

Background

The timing of acute myocardial infarction, sudden cardiac death, and ventricular arrhythmia demonstrates circadian and septadian periodicity, with a prominent peak in the morning hours, a sleep time nadir, and increased event rates on Mondays [1–8]. Sudden death and implantable cardioverter defibrillator (ICD) shocks have been reported to occur with higher frequency in the early morning hours in both ischemic and nonischemic cardiomyopathy [9 10]. These findings suggest that some triggering mechanisms for arrhythmic events are influenced by normal alterations in biorhythms. Biorhythmic fluctuations in platelet aggregation, blood pressure, heart rate, cortisol, catecholamine levels, vascular tone, and ischemia are thought to underlie the circadian patterning of myocardial infarction, ICD shocks, and sudden cardiac death [11–13].

Clinical management of heart failure, indications for ICD placement, and our ability to interrogate ICD electrograms have evolved significantly in the interval since earlier studies on timing and ICD shocks were performed. Recent analyses of temporal patterns of ventricular arrhythmia in subjects with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy, Brugada Syndrome, and Early Repolarization Syndrome showed substantial differences in timing of arrhythmia occurrence that may indicate differences in arrhythmia triggering mechanisms in varying pathologies [14 15]. This may have therapeutic implications, since a vagally mediated arrhythmogenic process would be targeted differently than a sympathetically driven process. Although current conceptual models of chronobiologic rhythms and their impact on ventricular arrhythmogenesis have highlighted rhythmic variability in sympathetic nervous system input as a major triggering mechanism, the data supporting this are conflicting [16]. Notably, adrenergic blockade has been shown in small studies to abolish the typical early morning VA peak [17], and in other studies to leave typical circadian patterns unaffected [18]. In an analogous area of cardiovascular disease, evidence has suggested that hypertension chronotherapy – reestablishing normal circadian patterns in blood pressure by systematic scheduling of medication dosing – is associated with significant reduction in cardiovascular events [19]. Using the Sudden Cardiac Death in Heart Failure Trial (SCD-HeFT) primary prevention ICD population, we sought to determine whether the timing of ICD therapies for life-threatening ventricular arrhythmia (VA) (1) manifests circadian and septadian variation, and (2) whether that pattern is importantly modified by specific patient characteristics or heart failure therapies.

Methods

Details of the SCD-HeFT trial have been previously published [20]. In brief, from September 16, 1997, to July 18, 2001, 2521 subjects were randomly assigned to receive placebo (847 subjects), amiodarone (845 subjects), or a single-chamber ICD programmed to shock-only mode (Medtronic 7223; 829 subjects, of which 811 received an ICD). Patients enrolled were at least 18 years of age and had New York Heart Association (NYHA) class II or III chronic, stable heart failure due to ischemic or nonischemic causes and a left ventricular ejection fraction (EF) of no more than 35 percent. All patients signed an informed consent and the study was approved by the human subjects committees of each participating institution. The ICD was programmed to have a single zone of therapy, and an episode of tachycardia was defined as at least 18 of 24 sequential beats at a detection rate of 187.5 beats per minute or more. Anti-tachycardia pacing was not specified in the protocol, but was programmed in a small number of subjects. In contrast to prior publications [21], this analysis included subjects who received either shocks or anti-tachycardia pacing therapy for events classified by the electrogram committee as an appropriate therapy for ventricular tachycardia or ventricular fibrillation. Subjects were followed every three months with alternating clinic visits and telephone calls. Data from the ICD memory log were regularly downloaded at these visits. The time and date of each episode was collected. For subjects with arrhythmic storm, events separated by < 1 minute were counted as the same event.

Data Analysis

Baseline characteristics are summarized as median (25th, 75th percentile) for continuous variables and percent (number) for categorical variables. Timing of episode occurrence was examined in two ways: (1) on a per-episode basis, considering each episode as a separate observation and giving each episode equal weight in the analysis, and (2) on a per-patient basis, considering each patient as a separate observation and giving each patient equal weight in the analysis. The latter approach circumvents the issue of the statistical results being dominated by a few patients with a large number of events. Based on time of occurrence, each ICD therapy was assigned to one of four time intervals (24 hour clock starting at midnight): 24:00 to 6:00, 6:00 to 12:00, 12:00 to 18:00, and 18:00 to 24:00. For each 6-hour time interval, the proportion of all episodes occurring during that interval was calculated for the per-episode approach. For the per-patient approach, we calculated a weighted frequency for each patient equal to the proportion of episodes weighted by the inverse of the total episodes (for example, a patient with 1 episode in a given interval out of 4 total episodes would have a weighted frequency of 0.25 for that interval).

We tested 3 hypotheses: (1) Morning peak: that the morning interval of 6 a.m. to noon, representing 0.25 of the 24-hour period, would have more than 0.25 of the episodes; (2) Early morning nadir: that the early morning interval of midnight to 6 a.m., again representing 0.25 of the 24-hour period, would have less than 0.25 of the episodes; (3) Monday peak: that Monday, representing 0.143 (1/7) of the week, would have more than 0.143 of the episodes. Each of these hypotheses was tested for both the per-episode approach, using generalized estimating equations to account for intra-patient correlation between episodes, and the per-patient approach, using a t-test to compare the sample mean weighted frequency to the stated value. However, because the results of the two sets of analyses were quite similar, only the results of the per-patient analysis are shown. All hypothesis tests were carried out in the entire cohort of patients with ventricular arrhythmias as well as subgroups defined by heart failure etiology, NYHA class, age (≤ and > 50 years), gender, EF (≤ and > 25%), and baseline beta-blocker use. All hypothesis tests were one-sided and p<0.05 was considered significant. All analyses were conducted with SAS v. 9.2 (SAS Institute, Cary NC).

Results

A total of 714 ICD therapies for life-threatening VA occurred in 186 subjects. Baseline characteristics are presented in Table 1. Among the patients experiencing appropriate ICD therapy for VA, the median age was 63 years, and the majority of the subjects were male (79%). At enrollment, 56% of the subjects were treated with a beta-blocker and 82% with an angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitor. Ischemic cardiomyopathy was present in 51%, and 64% were NYHA class II CHF.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of all SCD-HeFT subjects who received ICDs and subjects with spontaneous ICD therapy for ventricular arrhythmia

| Variable | All ICD pts (N=811) | VT/VF pts (N=186) |

|---|---|---|

|

| ||

| Age | 60 (52, 69) | 63 (53, 69) |

|

| ||

| Male | 77% (626) | 79% (147) |

|

| ||

| EF* | 24 (19, 30) | 20 (18, 26) |

|

| ||

| Beta blocker | 70% (565) | 56% (105) |

|

| ||

| ACE inhibitor† or ARB ‡ | 94% (766) | 94% (175) |

|

| ||

| Statin | 38% (305) | 34% (63) |

|

| ||

| NYHA § class | ||

| II | 68% (554) | 64% (119) |

| III | 32% (257) | 36% (67) |

|

| ||

| HF || etiology | ||

| Ischemic | 52% (420) | 51% (94) |

| Non-ischemic | 48% (391) | 49% (92) |

Age and EF are median (25th, 75th percentile). Others are percent (number).

EF = ejection fraction,

ACE = angiotensin converting enzyme,

ARB = angiotensin receptor blockade,

NYHA =New York Heart Association,

HF = heart failure

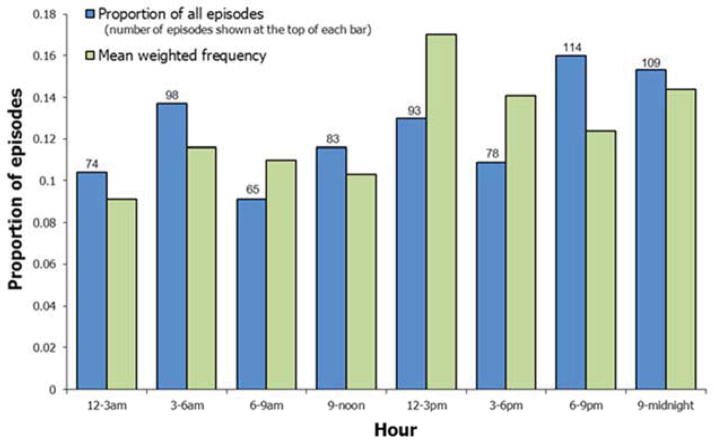

The distribution of ICD therapies over the 24 hour period, in 3-hour increments, is shown in Figure 1. No clear pattern is evident. The proportion of ICD therapies occurring in the typical morning 6 a.m. to 12 noon interval was not significantly greater than 0.25, either overall or for any subgroup (all p > 0.2, Table 2). In fact, for almost all subgroups, both the proportion of episodes and the mean weighted frequency during these morning hours were < 0.25.

Figure 1. ICD therapies for ventricular arrhythmias during the 24-hour period.

Blue bars show the proportion of all episodes that occurred during each 3-hour period. Green bars show the proportion of episodes, calculated for each patient and then averaged across patients, that occurred during each 3-hour period.

Table 2.

Proportion and weighted frequency of events occurring in the morning (6 a.m. to noon) vs. the rest of the 24 hours.

| Patient group | N patient | Total episodes in group | Proportion (N) occurring during morning interval | Proportion (N) occurring during other times | Mean weighted frequency during morning interval | Mean weighted frequency during other times | p* |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All patients | 186 | 714 | 0.207 (148) | 0.793 (566) | 0.213 | 0.787 | 0.93 |

| HF etiology | |||||||

| Ischemic | 94 | 351 | 0.182 (64) | 0.818 (287) | 0.218 | 0.782 | 0.80 |

| Non-ischemic | 92 | 363 | 0.231 (84) | 0.769 (279) | 0.208 | 0.792 | 0.90 |

| NYHA Class | |||||||

| II | 119 | 450 | 0.160 (72) | 0.840 (378) | 0.175 | 0.825 | 0.99 |

| III | 67 | 264 | 0.288 (76) | 0.712 (188) | 0.281 | 0.719 | 0.25 |

| Ejection fraction | |||||||

| > 25% | 47 | 210 | 0.195 (41) | 0.805 (169) | 0.153 | 0.847 | 0.99 |

| ≤ 25% | 139 | 504 | 0.212 (107) | 0.788 (397) | 0.234 | 0.766 | 0.71 |

| Age | |||||||

| > 50 years | 155 | 569 | 0.190 (108) | 0.810 (461) | 0.214 | 0.786 | 0.90 |

| ≤ 50 years | 31 | 145 | 0.276 (40) | 0.724 (105) | 0.212 | 0.788 | 0.77 |

| On beta blocker at baseline | |||||||

| Yes | 105 | 459 | 0.198 (91) | 0.802 (368) | 0.175 | 0.825 | 0.99 |

| No | 81 | 255 | 0.224 (57) | 0.776 (198) | 0.263 | 0.737 | 0.38 |

| Gender | |||||||

| Women | 39 | 148 | 0.216 (32) | 0.784 (116) | 0.223 | 0.777 | 0.67 |

| Men | 147 | 566 | 0.205 (116) | 0.795 (450) | 0.211 | 0.789 | 0.92 |

P-values are from tests of the hypothesis that mean weighted frequency > 0.25, i.e., that the proportion of patients’ events occurring from 6 a.m. to noon is greater than one quarter.

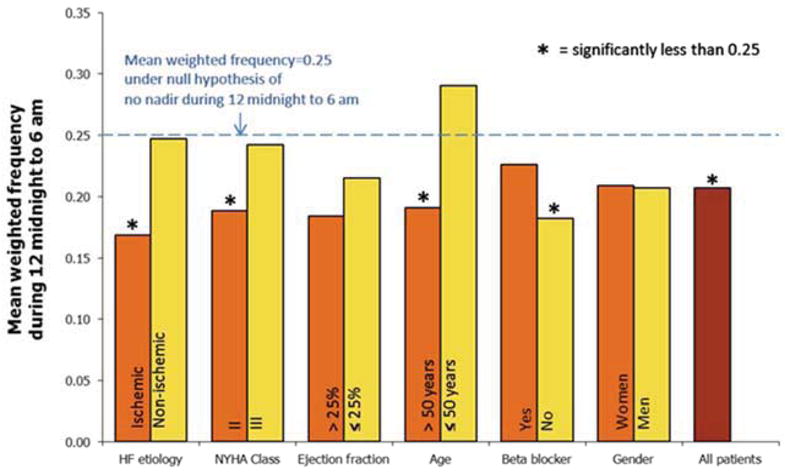

The proportion of ICD therapies occurring in the typical nadir of 12 midnight to 6 a.m. interval is shown in Table 3 and Figure 2. In the cohort overall; and among patients who were ischemic, NYHA Class II, older, or not on a beta blocker; the proportion of events occurring during this interval was significantly less than 0.25 (all p < 0.05), with weighted frequency of 0.21 for all patients and a range of 0.17 to 0.19 for the four subgroups above. Proportions are closer to 0.25 than weighted frequencies in most subgroups, indicating that proportions are influenced by a subset of patients with a larger number of episodes during the interval.

Table 3.

Proportion and weighted frequency of events occurring in the early morning (midnight to 6 a.m.) vs. the rest of the 24 hours.

| Patient group | Proportion (N) occurring during night interval | Proportion (N) occurring during other times | Mean weighted frequency during night interval | Mean weighted frequency during other times | p* |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All patients | 0.241 (172) | 0.759 (542) | 0.207 | 0.793 | 0.048 |

| HF etiology | |||||

| Ischemic | 0.236 (83) | 0.764 (268) | 0.168 | 0.832 | 0.0092 |

| Non-ischemic | 0.245 (89) | 0.755 (274) | 0.247 | 0.753 | 0.47 |

| NYHA Class | |||||

| II | 0.233 (105) | 0.767 (345) | 0.188 | 0.812 | 0.023 |

| III | 0.254 (67) | 0.746 (197) | 0.242 | 0.758 | 0.43 |

| Ejection fraction | |||||

| > 25% | 0.238 (50) | 0.762 (160) | 0.184 | 0.816 | 0.081 |

| ≤ 25% | 0.242 (122) | 0.758 (382) | 0.215 | 0.785 | 0.13 |

| Age | |||||

| > 50 years | 0.241 (137) | 0.759 (432) | 0.191 | 0.809 | 0.016 |

| ≤ 50 years | 0.241 (35) | 0.759 (110) | 0.290 | 0.710 | 0.72 |

| On beta blocker at baseline | |||||

| Yes | 0.251 (115) | 0.749 (344) | 0.226 | 0.774 | 0.26 |

| No | 0.224 (57) | 0.776 (198) | 0.182 | 0.818 | 0.032 |

| Gender | |||||

| Women | 0.270 (40) | 0.730 (108) | 0.209 | 0.791 | 0.25 |

| Men | 0.233 (132) | 0.767 (434) | 0.207 | 0.793 | 0.064 |

P-values are from tests of the hypothesis that mean weighted frequency < 0.25, i.e., that the proportion of patients’ events occurring from midnight to 6 a.m. is less than one quarter.

Figure 2. Mean weighted frequency of ICD therapies during the 12 midnight to 6 a.m. interval, overall and by subgroup.

Bars show the average proportion of each patient’s episodes that occurred between midnight and 6 a.m. Asterisks denote subgroups in which this average proportion is less than 0.25, the proportion under the null hypothesis.

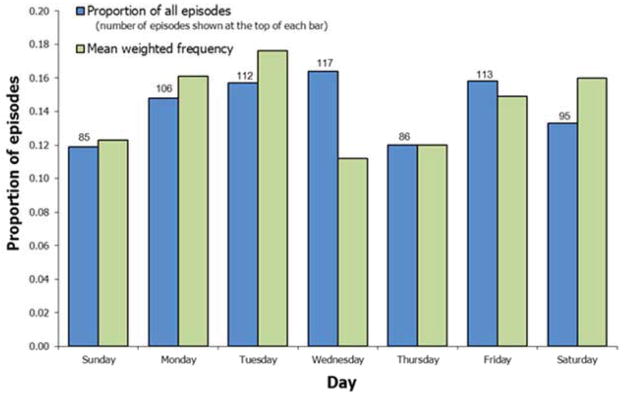

The distribution of ICD therapies over the 7 day week for all patients is shown in Figure 3. In general, lowest proportions occur on Sundays and Thursdays, and highest proportions on Tuesdays or Wednesdays. The proportion of therapies on Mondays was not significantly greater than 1/7 for the entire cohort, or for any subgroup except those patients not on beta blockade (Table 4). Among these patients, the mean weighted frequency was 0.22, indicating that nearly a quarter of their episodes occurred on Mondays.

Figure 3. ICD therapies for ventricular arrhythmias during the 7-day week.

Blue bars show the proportion of all episodes that occurred during each day. Green bars show the proportion of episodes, calculated for each patient and then averaged across patients, that occurred during each day.

Table 4.

Proportion and weighted frequency of events occurring on Mondays vs. the rest of the week.

| Patient group | Proportion (N) occurring on Mondays | Proportion (N) occurring on other days | Mean weighted frequency on Mondays | Mean weighted frequency on other days | p* |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All patients | 0.148 (106) | 0.852 (608) | 0.161 | 0.839 | 0.22 |

| HF etiology | |||||

| Ischemic | 0.128 (45) | 0.872 (306) | 0.153 | 0.847 | 0.38 |

| Non-ischemic | 0.168 (61) | 0.832 (302) | 0.168 | 0.832 | 0.21 |

| NYHA Class | |||||

| II | 0.149 (67) | 0.851 (383) | 0.164 | 0.836 | 0.24 |

| III | 0.148 (39) | 0.852 (225) | 0.155 | 0.845 | 0.37 |

| Ejection fraction | |||||

| > 25% | 0.171 (36) | 0.829 (174) | 0.151 | 0.849 | 0.44 |

| ≤ 25% | 0.139 (70) | 0.861 (434) | 0.164 | 0.836 | 0.21 |

| Age | |||||

| > 50 years | 0.155 (88) | 0.845 (481) | 0.160 | 0.840 | 0.26 |

| ≤ 50 years | 0.124 (18) | 0.876 (127) | 0.166 | 0.834 | 0.33 |

| On beta blocker at baseline | |||||

| Yes | 0.150 (69) | 0.850 (390) | 0.115 | 0.885 | 0.85 |

| No | 0.145 (37) | 0.855 (218) | 0.220 | 0.780 | 0.029 |

| Gender | |||||

| Women | 0.209 (31) | 0.791 (117) | 0.153 | 0.847 | 0.43 |

| Men | 0.133 (75) | 0.867 (491) | 0.163 | 0.837 | 0.22 |

P-values are from tests of the hypothesis that mean weighted frequency > 0.143, i.e., that the proportion of patients’ events occurring on Mondays is greater than 1/7.

Discussion

Analysis of the timing of ICD therapy for life threatening ventricular arrhythmias in the SCD-HeFT cohort revealed a typical early morning nadir of VA, but no early morning peak or Monday predominance. Additionally, subgroup analysis showed the early morning nadir in ischemics, NYHA class II heart failure, age < 50 years, and those not on a beta-blocker. Conversely, we did not see a typical morning peak of arrhythmia in any subgroup stratified by sex, heart failure etiology, heart failure class, or beta-blocker use. Septadian (weekly) variation was seen only in the subgroup not on beta-blockers.

Multiple prior studies have shown a circadian pattern of ICD firing, with a prominent morning peak, often a smaller secondary late afternoon peak, and an early a.m. nadir [4 5 22–24]. Tofler et al, in the first large study of the timing of ICD shocks, analyzed data from 483 patients with a Ventak PRx ICD implanted between 1990 and 1993 [8]. A circadian pattern with a peak between 9 a.m. and noon, and a nadir between 3 and 6 a.m. was seen in both groups (p<0.001). The results did not differ within subgroups of age, sex, EF, NYHA class, or heart failure etiology. The group with EF < 20% or NYHA class III CHF was notable for an attenuated nighttime fall in arrhythmia frequency and a blunted morning peak. Mallavarapu et al. analyzed the timing of ventricular arrhythmia episodes in 390 patients with healed myocardial infarction, and assessed whether the circadian pattern was influenced by gender, age, left ventricular function, or ventricular tachycardia cycle length < or > 300 ms [25]. A total of 15,731 device detections occurred, of which 2,692 electrograms were available and consistent with ventricular arrhythmia (2,488 episodes treated, 208 episodes with therapy aborted). Circadian variation in the occurrence of ventricular arrhythmia was evident, with the highest rate between 10:00 and 11:00 a.m., and the lowest between 2:00 and 3:00 a.m. This pattern persisted regardless of subgroup.

In two analyses, Peters et al. investigated the septadian distribution of ICD shocks, and the interaction of septadian and circadian rhythms in 683 patients with a Ventak PRx ICD [7 26]. The circadian pattern of ICD shock for episodes with cycle length < 280ms showed a broad peak between 9 a.m. and 6 p.m., and a long nadir between 9 p.m. and 6 a.m. The daily event timing distribution was strikingly similar for each day of the week, despite twice as many discharges on Mondays as compared with Saturdays. The circadian variation was independent of age, sex, EF, NYHA class, etiology of heart failure and use of antiarrhythmic drugs, but was not seen in patients on beta-blockers.

Prior large and small studies predominantly included subjects with coronary artery disease. Englund et al. reported an analysis of a more mixed population of ischemic and non-ischemic CHF [27]. Between 1993 and 1994, 820 patients received an ICD, 310 of which had an episode of ventricular arrhythmia. Both groups had similar circadian patterns of events, with a pronounced morning and a less pronounced afternoon peak. Analogous data showing similar circadian distributions of ventricular tachycardia episodes in ischemic and nonischemic cardiomyopathy were also reported by Grimm et. al [10].

Several prior studies have investigated the relationship between NYHA class or ejection fraction and circadian pattern of VA [4 5 8 22 25]. Three studies did not show a difference in timing of VA in subgroup analysis that included EF or NYHA class [5 22 25], whereas Behrens et al. found no typical circadian pattern in class III subjects, and Tofler et al. described a blunted morning peak and attenuation of the nighttime nadir in class IV subjects, and those with EF < 20% [4 8]. In our study, an early nadir was found in the overall cohort, but in subgroup analysis only in subjects with class II heart failure, ischemic cardiomyopathy, age < 50 years, and those on beta-blocker. It is curious that both the older and sicker patients have an attenuated circadian pattern, as well as the non-ischemics and those treated with adrenergic blockade. A critical difference in our population compared with prior studies is the mean EF of 20%; the mean EF of all prior studies but one was >30%. This difference may play a fundamental role in the dissimilarity of specific triggers for episodes of VA, or may reflect other pathways of autonomic dysregulation, such as severe heart failure.

Our study population differs from prior reports in ways important to the underlying pathophysiologic processes involved in arrhythmia generation. The SCD-HeFT study was a prospective randomized clinical trial designed to evaluate ICD therapy in the primary prevention of sudden cardiac death. Prior studies on biorhythmic effects on ventricular arrhythmia occurrence have examined predominantly secondary prevention patients, with predominant ischemic heart disease and higher ejection fractions. In our study, stored electrograms for each episode were available and adjudicated by the SCD-HeFT electrogram committee, data that were similarly available in only one prior study. Since the majority of the foundational research in the area of circadian variation in ICD shocks was performed over a decade ago, major changes in heart failure therapy have occurred. Over 90% of the SCD-HeFT ICD subjects were treated with ACE-inhibitors or angiotensin receptor blockade, the majority were on beta-blockade, and 38% were on a statin. Given the myriad effects of these agents, which includes anti-ischemic, anti-inflammatory, and vasodilatory properties, any of these agents, or a synergistic combination, may account for the attenuation in usual circadian patterns seen in this study.

The influence of circadian rhythms of the occurrence of cardiovascular events is often explained by a morning surge of sympathetic nervous system activity resulting in physiologic changes that produce myocardial ischemia [11 13]. This has also led to the hypothesis that a subset of episodes of ventricular arrhythmias and sudden cardiac death corresponding to these circadian surges may be aborted by treating patients with beta blockers. Notably, the significant result in the full cohort is driven by the pattern in the patients with ischemic cardiomyopathy. Our findings support the ischemia hypothesis in that we found an attenuation of circadian and septadian rhythms in subjects on beta-blockers; in the SCD-HeFT ICD arm, 57% of the subjects who received ICD shocks for ventricular arrhythmias and 70% of all patients who received an ICD were treated with beta-blockade. It is tempting to speculate that the increased rate of neurohormonal suppression of adrenergic triggers of ventricular arrhythmias modulated the previously observed circadian and septadian patterns. Additional evidence for this is that the SCD-HeFT subgroup of subjects not on beta-blockers showed more traditional variation in timing of arrhythmia, with the early morning nadir, and increased prevalence on Mondays.

Limitations of this study include the post-hoc nature of the analysis. Additionally important to note was the lack of data regarding work schedules or sleep-wake schedules, timing of medication ingestion, or alcohol, caffeine and other sympathomimetic substance consumption.

Conclusion

In the SCD-HeFT primary prevention population, the time distribution of ICD therapies for life threatening ventricular arrhythmia shows an early morning nadir in occurrence of ventricular arrhythmia, but no overall typical morning peak or Monday increase in events. Subgroup analysis showed a more prominent typical early morning nadir in ischemics, class II HF, and younger subjects. Subjects not on beta-blocker therapy also demonstrated an increased event rate on Mondays. These findings may indicate suppression of neurohormonal triggers with current heart failure therapy.

Abbreviations List

- VA

ventricular arrhythmia

- ICD

implantable cardioverter defibrillator

- SCD-HeFT

Sudden Cardiac Death in Heart Failure Trial

Footnotes

Relationship with industry: Dr. Patton reports having been a site investigator in a Cameron Health clinical trial. Dr. Poole reports having received lecture fees from Medtronic, Boston Scientific/Guidant, Biotronik, and St. Jude Medical, consulting fees from Physio Control, receiving equity in Cameron Health, and serving on the advisory board for Boston Scientific. George Johnson has no financial disclosures to report. Jill Anderson reports having received consulting fees from Boston Scientific, Inc. Anne Hellkamp has no financial disclosures to report. Dr. Mark reports having received consulting fees and research grants from Medtronic. Dr. Lee reports having received research grants and consulting fees from Medtronic. Dr. Bardy reports having research grants from the National Heart Lung and Blood Institute and St. Jude Medical. Dr. Bardy also holds equity and intellectual property rights with Cameron Health. No other potential conflicts of interest relevant to this article were reported.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Muller J, Stone P, Turi Z, et al. Circadian variation in the frequency of onset of acute myocardial infarction. N Engl J Med. 1985;313(21):1315–22. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198511213132103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Muller J, Ludmer P, Willich S, et al. Circadian variation in the frequency of sudden cardiac death. Circulation. 1987;75(1):131–38. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.75.1.131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Willich SN, Levy D, Rocco MB, Tofler GH, Stone PH, Muller JE. Circadian variation in the incidence of sudden cardiac death in the Framingham Heart Study population. Am J Cardiol. 1987;60(10):801–06. doi: 10.1016/0002-9149(87)91027-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Behrens S, Galecka M, Bruggemann T, et al. Circadian variation of sustained ventricular tachyarrhythmias terminated by appropriate shocks in patients with an implantable cardioverter defibrillator. Am Heart J. 1995;130(1):79–84. doi: 10.1016/0002-8703(95)90239-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lampert R, Rosenfeld L, Batsford W, Lee F, McPherson C. Circadian variation of sustained ventricular tachycardia in patients with coronary artery disease and implantable cardioverter- defibrillators. Circulation. 1994;90(1):241–47. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.90.1.241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Arntz H-R, Willich SN, Schreiber C, Bruggemann T, Stern R, Schultheiss H-P. Diurnal, weekly and seasonal variation of sudden death. Population-based analysis of 24061 consecutive cases. Eur Heart J. 2000;21(4):315–20. doi: 10.1053/euhj.1999.1739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Peters RW, McQuillan S, Gold MR. Interaction of septadian and circadian rhythms in life-threatening ventricular arrhythmias in patients with implantable cardioverter-defibrillators. The American Journal of Cardiology. 1999;84(5):555–57. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9149(99)00376-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tofler GH, Gebara OCE, Mittleman MA, et al. Morning Peak in Ventricular Tachyarrhythmias Detected by Time of Implantable Cardioverter/Defibrillator Therapy. Circulation. 1995;92(5):1203–08. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.92.5.1203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Muller JE, Ludmer PL, Willich SN, et al. Circadian variation in the frequency of sudden cardiac death. Circulation. 1987;75(1):131–8. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.75.1.131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Grimm W, Walter M, Menz V, Hoffmann J, Maisch B. Circadian variation and onset mechanisms of ventricular tachyarrhythmias in patients with coronary disease versus idiopathic dilated cardiomyopathy. Pacing Clin Electrophysiol. 2000;23(11 Pt 2):1939–43. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-8159.2000.tb07057.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Muller J, Tofler G, Stone P. Circadian variation and triggers of onset of acute cardiovascular disease. Circulation. 1989;79(4):733–43. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.79.4.733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tofler G, Brezinski D, Schafer A, et al. Concurrent morning increase in platelet aggregability and the risk of myocardial infarction and sudden cardiac death. N Engl J Med. 1987;316(24):1514–18. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198706113162405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Willich S, Maclure M, Mittleman M, Arntz H, Muller J. Sudden cardiac death. Support for a role of triggering in causation. Circulation. 1993;87(5):1442–50. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.87.5.1442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Maron BJ, Semsarian C, Shen WK, et al. Circadian patterns in the occurrence of malignant ventricular tachyarrhythmias triggering defibrillator interventions in patients with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Heart Rhythm. 2009;6(5):599–602. doi: 10.1016/j.hrthm.2009.02.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kim SH, Nam GB, Baek S, et al. Circadian and seasonal variations of ventricular tachyarrhythmias in patients with early repolarization syndrome and Brugada syndrome: analysis of patients with implantable cardioverter defibrillator. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol. 2012;23(7):757–63. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-8167.2011.02287.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Portaluppi F, Tiseo R, Smolensky MH, Hermida RC, Ayala DE, Fabbian F. Circadian rhythms and cardiovascular health. Sleep Med Rev. 2012;16(2):151–66. S1087. doi: 10.1016/j.smrv.2011.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Behrens S, Ehlers C, Brüggemann T, et al. Modification of the circadian pattern of ventricular tachyarrhythmias by beta-blocker therapy. Clinical Cardiology. 1997;20(3):253–57. doi: 10.1002/clc.4960200313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nanthakumar K, Newman D, Paquette M, Greene M, Rakovich G, Dorian P. Circadian variation of sustained ventricular tachycardia in patients subject to standard adrenergic blockade. American heart journal. 1997;134(4):752–57. doi: 10.1016/s0002-8703(97)70060-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hermida RC, Ayala DE, Mojon A, Fernandez JR. Influence of Circadian Time of Hypertension Treatemnt on Cardiovascular Risk: Results of the MAPEC Study. Chronobiology International. 2010;27(8):1629–51. doi: 10.3109/07420528.2010.510230. published Online First: Epub Date. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bardy G, Lee K, Mark D, et al., editors. Sudden Cardiac Death-Heart Failure Trial (SCD-HeFT) New York: Marcel Dekker; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Poole JE, Johnson GW, Hellkamp AS, et al. Prognostic importance of defibrillator shocks in patients with heart failure. NEJM. 2008;359(10):1009–17. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa071098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.D’Avila A, Wellens F, Andries E, Brugada P. At what time are implantable defibrillator shocks delivered? : Evidence for individual circadian variance in sudden cardiac death. Eur Heart J. 1995;16(9):1231–33. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.eurheartj.a061080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wood MA, Simpson PM, London WB, et al. Circadian pattern of ventricular tachyarrhythmias in patients with implantable cardioverter-defibrillators. Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 1995;25(4):901–07. doi: 10.1016/0735-1097(94)00460-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nanthakumar K, Newman D, Paquette M, Greene M, Rakovich G, Dorian P. Circadian variation of sustained ventricular tachycardia in patients subject to standard adrenergic blockade. American Heart Journal. 1997;134(4):752–57. doi: 10.1016/s0002-8703(97)70060-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mallavarapu C, Pancholy S, Schwartzman D, et al. Circadian Variation of Ventricular Arrhythmia Recurrences After Cardioverter-Defibrillator Implantation in Patients With Healed Myocardial Infarcts. The American Journal of Cardiology. 1995;75(16):1140–44. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9149(99)80746-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Peters RW, McQuillan S, Resnick SK, Gold MR. Increased Monday Incidence of Life-Threatening Ventricular Arrhythmias: Experience With a Third-Generation Implantable Defibrillator. Circulation. 1996;94(6):1346–49. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.94.6.1346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Englund A, Behrens S, Wegscheider K, Rowland E. Circadian variation of malignant ventricular arrhythmias in patients with ischemic and nonischemic heart disease after cardioverter defibrillator implantation. Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 1999;34(5):1560–68. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(99)00369-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]