Abstract

Purpose of review

Respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) represents the most common respiratory pathogen observed worldwide in infants and young children and may play a role in the inception of recurrent wheezing and asthma in childhood. We discuss herein the recent hypothesis that RSV vertically transmitted from the mother to the fetus in utero causes persistent structural and functional changes in the developing lungs of the offspring, thereby predisposing to postnatal airway obstruction.

Recent findings

A number of observations in humans support the notion that extrapulmonary tissues may be infected hematogenously by RSV and harbor this virus allowing the persistence of latent infection. More recent data from animal models suggest that RSV can be transmitted across the placenta from the respiratory tract of the mother to that of the fetus, and persist in the lungs both during development, as well as during adulthood. Vertical RSV infection is associated with dysregulation of critical neurotrophic pathways during ontogenesis, leading to aberrant parasympathetic innervation and airway hyperreactivity after postnatal reinfection.

Summary

These new data challenge the current paradigm that acquisition of RSV infection occurs only after birth and shift attention to the prenatal effects of the virus, with the potential to result in more severe and lasting consequences by interfering with critical developmental processes. The most immediate implication is that prophylactic strategies targeted to the mother-fetus dyad may reduce the incidence of postviral sequelae like childhood wheezing and asthma.

Keywords: Asthma, Bronchiolitis, Nerve Growth Factor, Lung Development, Vertical Infection

WHAT IS KNOWN ABOUT RSV

RSV is the most frequent cause of bronchiolitis and pneumonia in infants and young children, and the significant global burden reflects the morbidity, mortality, and financial impact of this infection [1]. RNA viruses of the Paramyxoviridae family, such as RSV, are characterized by two surface glycoproteins, which are the major antigens critical for virulence. By 2 years of age, most children have developed this infection at least once, which is associated with approximately 24 hospitalizations per 1,000 infants and 1 million deaths worldwide per year. Previous infections do not lead to persistent immunity, and reinfection is common.

Routine transmission of RSV stems from the contact of the nasopharyngeal or conjunctival mucosa of uninfected infants with respiratory secretions of infected individuals. Viral shedding routinely persists for around 1 week, but it may persist for longer periods in immunocompromised individuals. Viral replication, which is initiated in the nasal mucosa, subsequently spreads throughout the respiratory tract, resulting in airflow obstruction caused by edema and necrosis of the respiratory mucosa. A complex inflammatory response is mounted by the host against the infecting virus, which involves the release of multiple cytokines and chemokines from epithelium and infiltrating immunocytes, local neuro-immune interactions, and mast cells degranulation accompanied by the generation and release of leukotrienes [1].

Infants infected by RSV typically present a constellation of upper respiratory symptoms, which subsequently progress to the lower respiratory tract and manifest with cough, wheeze, and increased work of breathing. Chest radiographs are most often characterized by hyperinflation, patchy infiltrates, and atelectasis. It is not uncommon for upper respiratory infections caused by RSV to have apnea as the presenting sign, particularly among young infants. The primary therapy for RSV is supportive in nature and is comprised of measures to ensure adequate oxygenation, improved respiratory toilet, and maintenance of appropriate fluid and nutritional requirements. Severe cases may lead to respiratory failure requiring continuous positive airway pressures or mechanical ventilatory support.

No vaccine currently exists for active prophylaxis against RSV [1]. A formalin-inactivated vaccine marketed in the United States in the 1960s had to be withdrawn because – in addition to being poorly immunogenic – it predisposed children to aberrant Th2-type immune responses and life-threatening disease upon subsequent exposure to wild type virus. Since then, a vast array of experimental approaches, ranging from purified capsid proteins to attenuated or inactivated virus, have failed to deliver a safe and effective vaccine. To date, the only safe and efficacious approach to RSV prophylaxis is the humanized monoclonal antibody palivizumab, which was introduced to the U.S. market in 1998, although its use is largely restricted to infants at high risk for severe disease due to high costs.

WHAT IS UNCLEAR ABOUT RSV

Shortly after the initial isolation and characterization of RSV as the etiologic agent of infant bronchiolitis, it became evident that the acute phase of this infection is often followed by episodes of wheezing that recur for months or years and usually lead to a physician diagnosis of asthma. Although a series of epidemiologic studies suggested a cause-effect relationship between RSV infection and asthma [2,3], such studies were not designed to determine whether early-life RSV lower respiratory tract infections are causing asthma, or whether post-RSV wheeze is a phenotype associated with children who already possess a genetic or epigenetic predisposition. Thus, there remains a need for well-designed randomized and controlled interventional trials, which explore specific prophylactic or therapeutic intervention to determine whether the prevention or delay of an initial RSV infection will impact the onset, incidence or severity of asthma later in life.

A few studies, which lacked randomization and blinding, suggested that palivizumab prophylaxis of early RSV infections in preterm-born infants reduces the incidence of wheezing in the first years of life [4]. Recently, this hypothesis was addressed by a multicenter, randomized, double blind-placebo controlled (DBPC) trial, which investigated a causal role of RSV infection in the pathogenesis of wheezing illness during the first year of life in 429 otherwise healthy infants born at 33 to 35 weeks gestational age [5]. Infants were randomized to receive either monthly palivizumab injections or placebo during the RSV season and the primary outcome variable was the total number of parent-reported wheezing days in the first year of life.

Consistent with the previous non-randomized data, the authors reported that RSV prophylaxis resulted in a relative reduction of 61% in the total number of wheezing days during the first year of life. They also reported a significant reduction in the percentage of infants with recurrent wheeze compared to placebo controls. Of interest, this trial found a significant protective effect of palivizumab regardless of whether the infant had a family history of atopy, whereas a previous non-randomized study had found a significant effect only in non-atopic infants.

These data provide robust initial evidence that RSV infection is an important mechanism in the pathogenesis of recurrent wheeze during the first years of life. However, this conclusion remains limited to preterm-born children, who are at higher risk for recurrent episodes of wheeze due to the potential for intrinsic hyperreactivity and immaturity of their airways. It remains to be seen whether the concept of RSV prophylaxis to prevent subsequent wheeze or development of asthma is applicable to healthy term infants who represent the majority of patients developing bronchiolitis and asthma. Thus, in order to reach a formal conclusion that then potential exists for largescale RSV prophylaxis to reduce the incidence of post-viral wheeze in childhood, it is critical to conduct independently funded, randomized, DBPC trials in which significant numbers of full-term born infants are enrolled.

A more complex challenge will be to shed a more definitive light onto the pathogenesis of virus-induced asthma and the complex network of inflammatory and immune pathways that link a very common, self-limiting, and usually benign infection acquired at the dawn of life with years of respiratory disease punctuated by more or less frequent attacks of acute bronchospasm, which is usually poorly responsive to conventional anti-asthma therapies and severe enough to warrant multiple hospitalizations, while creating havoc in the life of young patients and their families. The centerpiece of this challenge is to unravel how a virus like RSV, which is unable to integrate in the human genome and is typically cleared from the respiratory tract within a few weeks, can produce long-term sequelae. In particular, the critical question that has baffled generations of scientists is the following: Is viable RSV (or parts of its genome) able to persist in immunocompetent hosts after the acute infection is clinically resolved?

WHAT MAY EXPLAIN RSV

Although the tissue tropism of airway epithelial cells for RSV is well documented, several studies have reported that RSV infection is not always restricted to the respiratory tract. For example, RSV has been shown in a range of human tissues, which includes the central nervous system, heart, and liver. This is consistent with clinical manifestations that are not unusual in infants with severe RSV infections, such as apnea, seizures, increased cardiac and liver enzymes [6, 7]. Furthermore, a study based on the use of nested PCR detected RSV RNA in the blood of 63% of neonates and 20% of infants whose nasal washes resulted positive for RSV antigen. This observation raises the likelihood that the probability and/or severity of RSV viremia and extra-pulmonary dissemination are inversely proportional to age [8].

Surprisingly, RNA sequences with virtually complete homology to the RSV genome have been found in the bone marrow of two-thirds of adult subjects and all of the pediatric subjects tested in a recent study [9]. No homologous sequence was identified in the human genome database, confirming that the message was indeed of viral origin and that the bone marrow provides an extra-pulmonary target to blood-borne RSV (Figure 1). These findings raise the interesting hypothesis that RSV recirculates between the lungs and bone marrow, and may rely on leukocytes as active vectors, which has the potential to influence the severity of the acute infection and its chronic sequelae.

Figure 1. RSV detection in naïve human BMSC.

Eleven primary human BMSC lines derived from pediatric or adult donors were screened by RT-PCR using primers specific for the nucleocapsid (N) protein of RSV. Five of the 8 adult-derived BMSC lines (63%) and all 3 children-derived ones (100%) yielded a 380 bp product (top) whose sequence shared > 95% homology with the RSV genome (bottom). Homologous base pairs are marked by asterisks.

Viral persistence

Because RSV genomic sequences were amplified from the bone marrow of a large proportion of adult subjects, a critical corollary of the study cited above is that - after an acute respiratory infection - RSV may persist in a latent state outside of the respiratory tract. Indeed bone marrow stromal cells (BMSC) may be the potential sites of an extra-pulmonary sanctuary, i.e., an immunologically privileged location for the virus to establish a low-grade infection that could persist latently and potentially recur intermittently. This provides a reasonable pathophysiologic mechanism to explain chronic post-bronchiolitis airway dysfunction [9]. Interestingly, this hypothesis is supported by a subsequent study by a separate group of investigators who found that BMSC could also harbor latent Mycobacterium tuberculosis (MTB). They reported that viable MTB was found in human bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cells from patients who had successful resolution of the primary infection following completion of multi-drug anti-tubercular therapy [10].

Indeed, the chronic persistence of pathogens following acute infections and their complex interactions with the human genome have been known for years and have been extensively characterized not only for DNA viruses (e.g., herpesviruses, Epstein-Barr, adenovirus), but also for several RNA viruses (e.g., hepatitis C, rubella, measles). These viruses have in common the evolution of diverse molecular strategies able to evade immune defenses, and can reach a point of equilibrium with the host that limits viral replication to levels compatible with physiologic survival without obvious symptoms of infection: over time, this forms our own individual “virome”.

The biological equilibrium between the host and its endogenous virome is dynamic, and can be disrupted by changes in environmental or immunological variables leading to viral reactivation and new cycles of lytic replication. But even in a latent state, viruses can modulate long-term the host innate and adaptive immunity. In the specific case of RSV infection, the virus has structural consequences on the BMSC cytoskeleton and functional consequences on the synthesis of soluble cytokines and chemokines, which in turn results in an environment that favors maturation and mobilization of leukocytes to enter the blood stream and be directed to the infected lung tissues [9]. Infection of BMSC with live virus results in a reduced ability to support B cell maturation, which has the potential to interfere with the humoral immune response against the virus as well as co-infecting pathogens.

Vertical transmission

If RSV can reach extrapulmonary targets and persist there in latent form, this opens another – perhaps more frightening – Pandora’s Box: Can RSV travel from the airways of a pregnant mother with an acute upper respiratory infection, reach the fetus hematogenously through the placenta, and establish a persistent infection that affects ontogenesis and post-natal development? For many years, it has been generally accepted that the pathophysiology of RSV bronchiolitis is driven by the inflammatory response evoked by horizontal (i.e., interpersonal) transmission of the virus in the first few months after birth. However, a recently published study has brought to the forefront a striking new idea: RSV may be transmitted vertically from the respiratory tract of the mother to the lungs of the fetus [11]. Until now, we believed that when a pregnant woman got a cold, the developing fetus was protected by the placenta from RSV and other respiratory viruses.

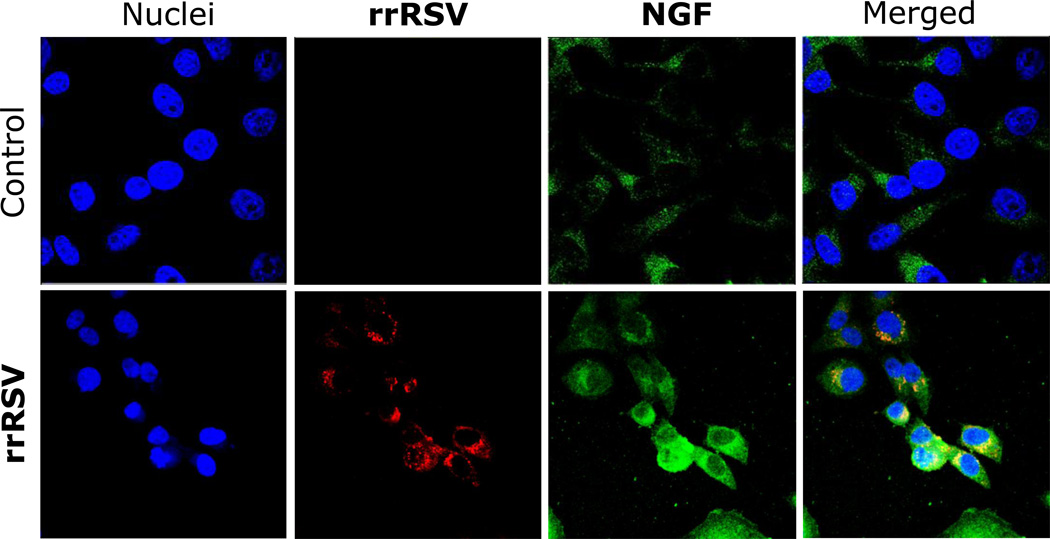

In this study, pregnant rats were inoculated with a recombinant RSV strain that could be tracked through expression of a red fluorescent protein (rrRSV). The same virus was subsequently found in 30 percent of fetuses exposed in utero (Figure 2), as well as in the lungs of 40 percent of newborn rats and 25 percent of rats born to inoculated mothers when tested in adulthood. These data provide proof of concept for the transplacental transmission of RSV from mother to offspring and the persistence of vertically transmitted virus in lungs after birth. Notably, the intrauterine RSV infection changed expression and function of critical neurotrophic pathways that control the development of cholinergic nerves in the budding airways and lung tissues [12].

Figure 2. Propagation of vertically transmitted RSV.

Magnified at 60×, extracts of whole fetuses are shown that were delivered from dams inoculated with recombinant RSV (rrRSV; bottom row) or from pathogen-free controls (top row) and co-cultured with human airway epithelial cells. The micrographs show red fluorescence in the cytoplasm of cells exposed to fetal extracts from rrRSV-infected dams, confirming the presence of actively replicating infectious virus associated with markedly increased green nerve growth factor (NGF) immunoreactivity.

These changes in cholinergic innervation of the fetal respiratory tract resulted in the development of postnatal airway hyperreactivity upon reinfection with the same virus [11]. The airway smooth muscle tone was normal in the absence of stimulation and its contraction was normal in the absence of either maternal or neonatal infection. But in pups reinfected with RSV after prenatal exposure to the virus, markedly potentiated contractile responses were measured after either electrical nerve stimulation or methacholine inhalation, suggesting the involvement of both pre- and postjunctional mechanisms (Figure 3). These findings are consistent and provide a plausible mechanism to the epidemiologic evidence that early-life RSV infection – or possibly reinfection – predisposes a subpopulation of children to recurrent wheezing and asthma that typically spans through the first decade of life even in the absence of atopic phenotype.

Figure 3. Innervation of RSV-infected fetal airways.

Confocal microscopy showing acetylcholine immunoreactivity (green) in the subepithelial neural plexus lining the lumen of fetal airways exposed in utero to RSV (asterisks). As a consequence, when pups delivered from RSV-infected dams were reinfected postnatally (group R+R) their airways became significantly hyperresponsive to electrical field stimulation of cholinergic nerves. In contrast, airway responses from pathogen-free pups delivered from pathogen-free dams (group C+C) were not affected by either prenatal (group R+C) or postnatal RSV infection (group C+R).

To our knowledge this is the first report of vertical transmission of RSV, or for that matter any common respiratory virus. A number of infectious agents, including herpesviruses and retroviruses, have been shown to cross the placenta and establish persistent infection in offspring. The new evidence extends this possibility to other infections, such as RSV, once regarded as temporary and localized and that instead may be longer lasting and more pervasive than we thought. Also, as shown for other viral pathogens, if RSV seeds the fetus before full T-cell maturation, this could lead to induction of prenatal tolerance and justify the limited synthesis of interferon and other inflammatory cytokines that have been noted when newborns develop severe infections.

Vertical RSV and asthma

The general concept that we have been working under for decades is that nothing bad happens in the lungs until the baby is born — even with serious conditions such as cystic fibrosis – and that the lungs are “clean” of pathogens at birth. But if human studies replicate the findings from animal models outlined above, our understanding of the pathogenesis of RSV infections would be completely changed. It would turn back the clock of respiratory developmental diseases by months and mean that we would need to start thinking about lung development and pathology during pregnancy rather than at birth. This could create a paradigm shift by extending our focus on prevention from the first few years after birth to also include the last few months before birth. This new paradigm is in line with the emerging evidence that many (or most) chronic inflammatory, degenerative, and even neoplastic diseases plaguing adults have their origins from often-subtle events occurring during fetal life. The “foetal programing hypothesis” was originally formulated by Dr. David Barker more than two decades ago to explain the extensively reproduced and confirmed epidemiologic evidence that low birth weight predisposes to cardiovascular disease in late adulthood.

Dr. Barker died aged 75 in September 2013, leaving the legacy of this initially controversial, but now widely accepted, idea that common chronic illnesses such as cancer, cardiovascular disease and diabetes result not always from bad genes and an unhealthy adult lifestyle, but from poor intrauterine and early postnatal health. In one of his last public speeches, he argued: "The next generation does not have to suffer from heart disease or osteoporosis. These diseases are not mandated by the human genome. They barely existed 100 years ago. They are unnecessary diseases. We could prevent them had we the will to do so." We believe the same concepts can be extended to chronic obstructive airway diseases like asthma and COPD.

Asthma is the final product of complex interactions between genetic and environmental variables (Figure 4). Prenatal events like the intrauterine exposure to viruses with specific tropism for the developing respiratory epithelium will cause a shift in the trajectory of structural and functional airway development toward a hyperreactive phenotype. The same intrauterine exposures can affect gene expression via epigenetic modifications like DNA methylation, histone acetylation, and by altering the relative expression of regulatory micro-RNAs. The resulting neonatal phenotype will predispose the child to aberrant responses to common respiratory infections and airborne irritants, thereby increasing the risk of obstructive lung disease later in life. Postnatal events, such as exposure to indoor and outdoor pollutants and allergens, can further shift the equilibrium of the adult phenotype by exacerbating airway inflammation and hyperreactivity. The continuous range of possible developmental trajectories and multiple sequential events acting during development will define the severity and duration of disease.

Figure 4. Fetal programming of asthmatic airways.

What makes our lungs prone to develop disease? Of course, genetic traits inherited from our parents are important role. But also the quantity and quality of food our mother eats, the pollution in the air she breathes, the infections she suffers during gestation will play a critical role throughout our life, perhaps even more important than genetics. In particular, prenatal events like the intrauterine exposure to viruses with specific tropism for the developing respiratory epithelium will cause a shift in the trajectory of structural and functional airway development toward a hyperreactive phenotype. The resulting neonatal phenotype may predispose the child to aberrant responses to common respiratory infections and airborne irritants, thereby increasing the risk of obstructive lung disease later in life. Postnatal events, such as exposure to indoor and outdoor pollutants and allergens, can further shift the equilibrium of the adult phenotype by exacerbating airway inflammation and hyperreactivity.

Dr. Barker believed that public health medicine was failing and that its cornerstone should be the protection of the nutrition of young women. Indeed, chronic disease like obesity, diabetes and asthma are becoming epidemic and their management in adulthood is escalating the costs of healthcare to proportions unsustainable for any world economy. If we want to prevail in the war against chronic airway diseases that so far have eluded any therapeutic strategy, it is essential to recognize that the months spent in our mothers’ womb may be the most consequential of our lives, and identify the intrauterine and early life events shaping the development of the respiratory system to prevent or redirect dysfunctional phenotypes before they result in actual disease. Prophylaxis of pregnant women against respiratory infections like RSV may become one day one of the first steps in this direction.

HIGHLIGHTS.

RSV is the most frequent cause of bronchiolitis and pneumonia in infants worldwide.

Early-life RSV infection is often followed by recurrent episodes of wheezing.

RSV genome has been found in the bone marrow stroma of adult and pediatric subjects.

RSV is able to spread across the placenta from the mother’s lungs to the fetus.

Vertical RSV infection predisposes the offspring to postnatal airway hyperreactivity.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The Authors thank the National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute of the National Institute of Health for the generous support of my research over the past 15 years. We are also very grateful to the many faculty, fellows, technical and administrative staff, without whom my research would not have been possible.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

There are no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

Papers of particular interest, published within the annual period of review, have been highlighted as:

• of special interest

•• of outstanding interest

- 1. Wright M, Piedimonte G. Respiratory syncytial virus prevention and therapy: past, present, and future. Pediatr Pulmonol. 2011;46:324–347. doi: 10.1002/ppul.21377. • A recent comprehensive review of RSV infection.

- 2.Sigurs N, Bjarnason R, Sigurbergsson F, Kjellman B. Respiratory syncytial virus bronchiolitis in infancy is an important risk factor for asthma and allergy at age 7. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2000;161:1501–1507. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.161.5.9906076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Stein RT, Sherrill D, Morgan WJ, Holberg CJ, Halonen M, Taussig LM, Wright AL, Martinez FD. Respiratory syncytial virus in early life and risk of wheeze and allergy by age 13 years. Lancet. 1999;354:541–545. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(98)10321-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Simões EA, Carbonell-Estrany X, Rieger CH, Mitchell I, Fredrick L, Groothuis JR. The effect of respiratory syncytial virus on subsequent recurrent wheezing in atopic and nonatopic children. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2010;126:256–262. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2010.05.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Blanken MO, Rovers MM, Molenaar JM, Winkler-Seinstra PL, Meijer A, Kimpen JL, Bont L, Dutch RSV. Neonatal Network: Respiratory syncytial virus and recurrent wheeze in healthy preterm infants. N Engl J Med. 2013;368:1791–1799. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1211917. •• DBPC trial showing that RSV prophylaxis results in a reduction the incidence of wheezing during the first year of life.

- 6.Eisenhut M. Extrapulmonary manifestations of severe respiratory syncytial virus infection - a systematic review. Crit Care. 2006;10:R107. doi: 10.1186/cc4984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Iankevich OD, Dreizin RS, Makhlinovskaia NL, Gorodnitskaia NA. Viremia in respiratory syncytial virus infection. Vopr Virusol. 1975;4:455–458. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rohwedder A, Keminer O, Forster J, Schneider K, Schneider E, Werchau H. Detection of respiratory syncytial virus RNA in blood of neonates by polymerase chain reaction. J Med Virol. 1998;54:320–327. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1096-9071(199804)54:4<320::aid-jmv13>3.0.co;2-j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Rezaee F, Gibson LF, Piktel D, Othumpangat S, Piedimonte G. Respiratory syncytial virus infection in human bone marrow stromal cells. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2011;45:277–286. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2010-0121OC. •• First evidence that RSV RNA is harbored in bone marrow stromal cells of children and adults.

- 10. Das B, Kashino SS, Pulu I, Kalita D, Swami V, Yeger H, Felsher DW, Campos-Neto A. CD271+ bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells may provide a niche for dormant Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Sci Transl Med. 2013;5:170ra113. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3004912. •• First evidence that MTB is harbored in bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells of patients who had successfully completed anti-tubercular therapy.

- 11. Piedimonte G, Walton C, Samsell L. Vertical transmission of respiratory syncytial virus modulates pre- and postnatal innervation and reactivity of rat airways. PLoS One. 2013;8:e61309. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0061309. •• First experimental evidence that RSV is vertically transmitted from the mother to the fetus and persists postnatally in the offspring lungs.

- 12.Scuri M, Samsell L, Piedimonte G. The role of neurotrophins in inflammation and allergy. Inflamm Allergy Drug Targets. 2010;9:173–180. doi: 10.2174/187152810792231913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]