Abstract

Background. Literature data suggest that cells such as mast cells (MCs), are involved in angiogenesis. MCs can stimulate angiogenesis by releasing of several proangiogenic cytokines stored in their cytoplasm. In particular MCs can release tryptase, a potent in vivo and in vitro proangiogenic factor. Nevertheless few data are available concerning the role of MCs positive to tryptase in primary pancreatic cancer angiogenesis. This study analyzed MCs and angiogenesis in primary tumour tissue from patients affected by pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma (PDAC). Method. A series of 31 PDAC patients with stage T2-3N0-1M0 (by AJCC for Pancreas Cancer Staging 7th Edition) was selected and then underwent surgery. Tumour tissue samples were evaluated by means of immunohistochemistry and image analysis methods in terms of number of MCs positive to tryptase (MCDPT), area occupied by MCs positive to tryptase (MCAPT), microvascular density (MVD), and endothelial area (EA). The above parameters were related to each other and to the main clinicopathological features. Results. A significant correlation between MCDPT, MCAPT, MVD, and EA group was found by Pearson's t-test analysis (r ranged from 0.69 to 0.81; P value ranged from 0.001 to 0.003). No other significant correlation was found. Conclusion. Our pilot data suggest that MCs positive to tryptase may play a role in PDAC angiogenesis and they could be further evaluated as a novel tumour biomarker and as a target of antiangiogenic therapy.

1. Introduction

Inflammatory cells, such as macrophages, lymphocytes, and mast cells (MCs), play a major role in tumour angiogenesis by means of angiogenic cytokines stored in their cytoplasm. MCs are involved in neovascularization in experimentally induced tumour, accumulate near to tumour cells before the angiogenesis onset, and participate in the metastatic spreading of primary tumours. MCs intervene in angiogenic process releasing classical proangiogenic factors, such as vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF), thymidine phosphorylase (TP), fibroblast growth factor-2 (FGF-2), and the nonclassical proangiogenic factor, namely, tryptase stored in their secretory granules [1–9]. The role of MCs has been broadly studied in benign lesions, in animal and human's cancers, such as keloids, mast cells tumours, and head and neck, colorectal, gastric, lung, and cutaneous malignancies, indicating that MCs density is highly correlated with the extent of tumour angiogenesis [10–14]. Recent data have shown that MCs density is correlated with angiogenesis and progression of patients with pancreatic cancer [15, 16]. However, no data have been published regarding the correlation each to other of MCs density positive to tryptase (MCDPT), area occupied by MCs positive to tryptase (MCAPT), microvascular density (MVD), endothelial area (EA) and the main clinicopathological features in primary tumour tissue of affected patients. To this end, we conducted a prospective study in a series of 31 pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma patients (PDACP) having undergone surgery with stage T2-3N0-1M0 (by AJCC for Pancreas Cancer Staging 7th Edition). Tumour tissue samples were evaluated by means of immunohistochemistry and image analysis methods, obtaining a significant correlation between MCDPT, MCAPT, MVD, and EA group. Our pilot data suggest that MCs positive to tryptase may play a role in PDAC angiogenesis and they could be further evaluated as a novel tumour biomarker and as a target of antiangiogenic therapy.

2. Patients and Methods

2.1. Patients

The clinicopathological features of selected patients are summarized in Table 1. A total of 31 PDACP patients underwent potential curative resection. Surgical approaches used were pancreaticoduodenectomy, distal pancreatectomy, and total pancreatectomy with lymph node dissection. Patients were staged according to the American Joint Committee on Cancer 7th Edition (AJCC-TNM) classification and the World Health Organization classification (2000 version) was used for pathologic grading. All patients had no distant metastases on computed tomography and ten patients had received neoadjuvant-therapy based on Gemcitabine or FOLFIRINOX. The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of “Mater Domini” Hospital, “Magna Graecia” University, Catanzaro, and from each enrolled patient the signed informed consent was obtained.

Table 1.

Clinicopathological features of patients.

| N | |

|---|---|

| Overall series | 31 |

| Age | |

| (i) <65 | 23 |

| (ii) >65 | 8 |

| Sex | |

| (i) Male | 25 |

| (ii) Female | 6 |

| Tumour site | |

| (i) Head | 13 |

| (ii) Body-Tail | 18 |

| TNM by AJCC for Pancreas Cancer Staging 7th Edition | |

| (i) T2N0-1M0 | 14 |

| (ii) T3N0-1M0 | 17 |

| Histologic type | |

| Ductal adenocarcinomas | 31 |

| Histologic grade | |

| (i) G1-G2 | 19 |

| (ii) G3 | 12 |

2.2. Immunohistochemistry

For the evaluation of MCDPT, MCAPT, MVD, and EA, a three-layer biotin-avidin-peroxidase system was utilized [17]. Briefly, 4 μm thick serial sections of formalin-fixed and paraffin-embedded surgically removed tumour samples were deparaffinised. Then, for antigen retrieval, sections were microwaved at 500 W for 10 min, after which endogenous peroxidase activity was blocked with 3% hydrogen peroxide solution. Next, adjacent slides were incubated with the monoclonal antibodies anti-CD31 (clone JC70a; Dako) diluted 1 : 40 for 30 min at room temperature and anti-tryptase (clone AA1; Dako, Glostrup, Denmark) diluted 1 : 100 for 1 h at room temperature. The bound antibody was visualised using biotinylated secondary antibody, avidin-biotin peroxidase complex, and fast red. Nuclear counterstaining was performed with Gill's haematoxylin number 2 (Polysciences, Warrington, PA, USA). Primary antibody was omitted in negative controls.

2.3. Morphometric Assay

An image analysis system (Semiquantimet 400 Nikon) was employed.

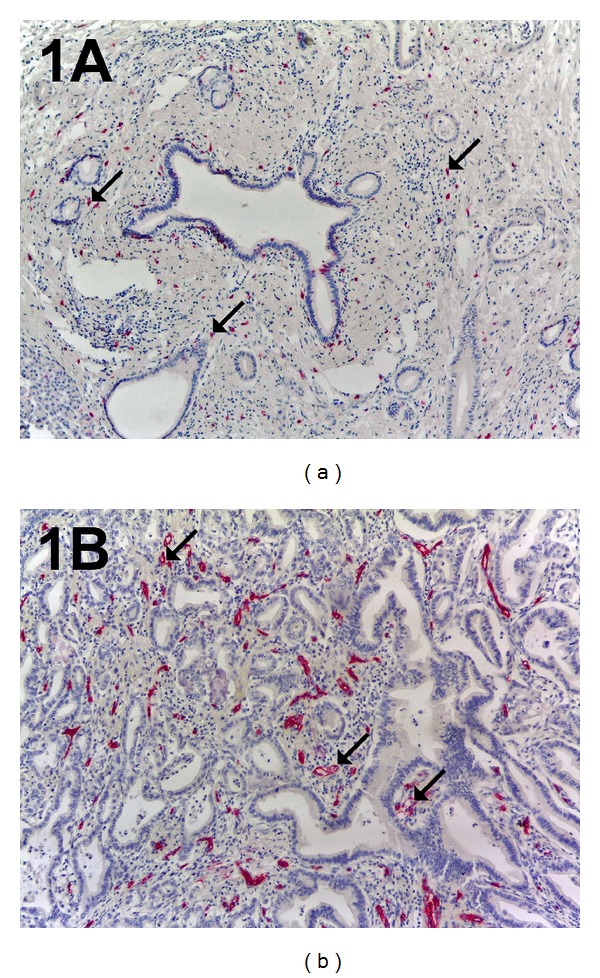

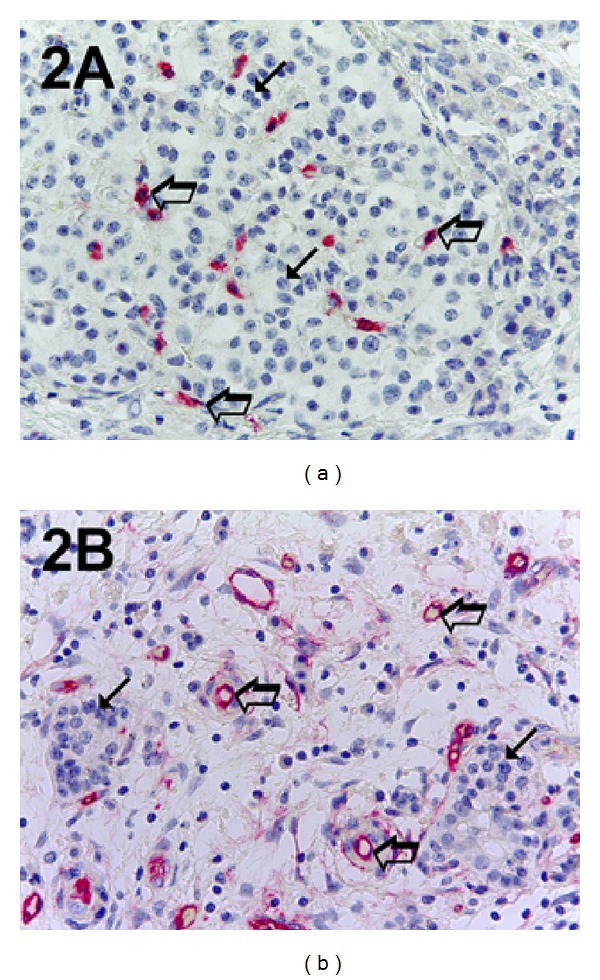

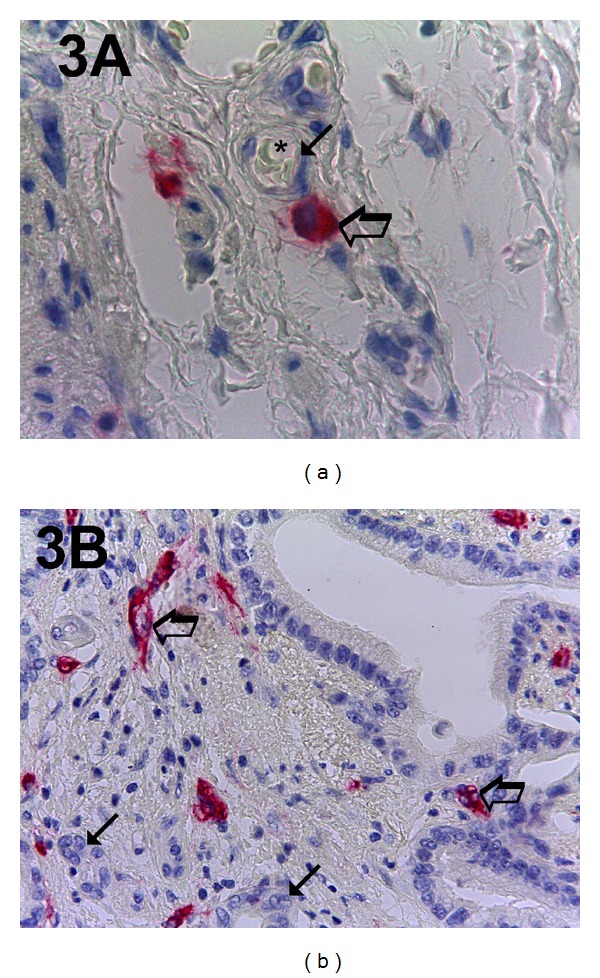

The five most vascularized areas (“hot spots”) were selected at low magnification and both MCDPT (Figure 1(a)) and individual vessel (Figure 1(b)) were counted at ×400 magnification (0.19 mm2 area; Figures 2(a) and 2(b)) (GR and NZ) [1]. Single red stained endothelial cells, endothelial cell clusters and microvessels, clearly separated from adjacent microvessels, tumor cells, and other connective tissue elements were counted [17]. Areas of necrosis were not considered for counting. In serial sections each single MC positive to tryptase was counted. Single red stained endothelial cells and red MCs positive to tryptase were also evaluated in terms of immunostained area at ×400 magnification (0.19 mm2 area) [17]. Finally morphological detail of both MCs positive to tryptase and endothelial cells was observed at ×1000 magnification in oil (Figures 3(a) and 3(b)).

Figure 1.

In (a) a pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma sample stained with the anti-tryptase antibody. Many scattered red immunostained MCs. Arrows indicate single MC. Magnification: in (b) a highly vascularized pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma sample stained with the anti-CD-31 antibody. Many red immunostained microvessels. Arrows indicate microvessel. Magnification: (a-b), ×100.

Figure 2.

In (a) pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma sample stained with the anti-tryptase antibody. Many scattered red immunostained MCs. Big arrows indicate single red MC and small arrows indicate the bleu nucleus of cancer cells. In (b) a highly vascularized pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma sample stained with the anti-CD-31 antibody. Big arrows indicate single red microvessels with a lumen and small arrows indicate the bleu nucleus of cancer cells. Magnification: (a-b), ×400.

Figure 3.

In (a) pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma sample stained with the anti-tryptase antibody. Big arrow indicates a single red MC and small arrow indicates a microvessel with its lumen. The lumen is marked with an asterisk and there are well visible intraluminal red blood cells. In (b) a highly vascularized pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma sample stained with the anti-CD-31 antibody. Big arrows indicate single red microvessels with their own lumen and small arrows indicate the bleu nucleus of cancer cells. Magnification: (a-b), ×1000 in oil.

2.4. Statistical Analysis

Linear correlations between MCDPT, MCAPT, MVD, and EA groups were quantified by means of Pearson's correlation coefficient (r). Correlation between MCDPT, MCAPT, MVD, and EA groups and the main clinicopathological features were analysed by chi-square test. In all analyses a P < 0.05 was considered significant. All statistical analyses were performed with the SPSS statistical software package (SPSS, Inc., Chicago, IL).

3. Results

Immunohistochemical staining by using the antibodies anti-CD31 and anti-tryptase allows demonstration of that in highly vascularized cancer tissue; MCs positive to tryptase are well recognizable and generally they are located in perivascular position (Figure 3(a)).

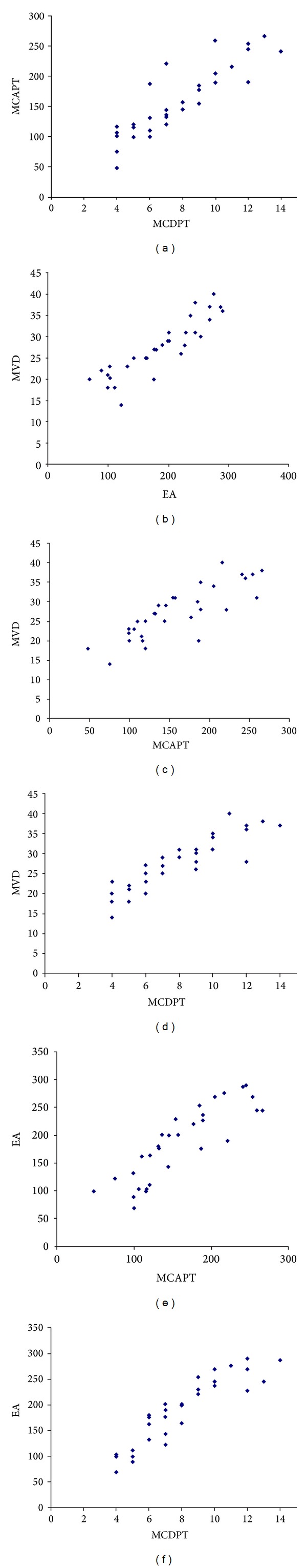

Mean values ± 1 SD of all the tissue evaluated parameters are reported in Table 2. There was a significant correlation between MCDPT and MVD (r = 0.81; P = 0.001), between MCAPT and MVD (r = 0.69; P = 0.003), between MCDPT and EA (r = 0.76; P = 0.002), between MCAPT and EA (r = 0.73; P = 0.002), between MVD and EA (r = 0.80; P = 0.001), and between MCDPT and MCAPT (r = 0.77; P = 0.001) (Figure 4). No correlation concerning MCDPT, MCAPT, MVD, EA, and the main clinicopathological features was found.

Table 2.

MCAPT, MCDPT, EA, and MVD means ± 1 standard deviations.

| MCDPT ×400 magnification (0.19 mm2 area) |

MCAPT ×400 magnification (0.19 mm2 area) |

EA ×400 magnification (0.19 mm2 area) |

MVD ×400 magnification (0.19 mm2 area) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 8 ± 3a | 159.38μ 2a ± 58.30a | 186.06μ 2a ± 65.89 | 27 ± 8a |

aMean ± 1 standard deviation.

Figure 4.

Correlation analysis between MCDPT and MVD (r = 0.81; P = 0.001), MCAPT and MVD (r = 0.69; P = 0.003), MCDPT and EA (r = 0.76; P = 0.002), MCAPT and EA (r = 0.73; P = 0.002), MVD and EA (r = 0.80; P = 0.001), and MCDPT and MCAPT (r = 0.77; P = 0.001).

4. Discussion

MCs' involvement in tumour angiogenesis has been demonstrated in several animals models and human malignancies [10–14, 18–20].

MCs are recruited and activated via several factors secreted by tumour cells, such as the C-Kit receptor or stem cells factor, VEGF, FGF-2, and TP. In tumour microenvironment, MCs secrete both gelatinases A and B which, in turn, degrade extracellular matrix, releasing stored angiogenic factors [21–33].

On the other hand, MCs may induce angiogenesis by several proangiogenic factors stored in their secretory granules, such as VEGF, FGF-2, tumour necrosis factor alpha, and interleukin 8, transforming growth factor beta, heparin, and tryptase. With special reference to the last, it is involved in tumour angiogenesis stimulating the formation of vascular tubes in in vitro and in vivo experimental models and it is also an agonist of the PAR-2 in vascular endothelial cells that, in turn, induces angiogenesis. Interestingly in several human malignancies but not in pancreatic cancer, MCDPT and MCAPT have been associated with tumour angiogenesis. In this regard experimental results suggested that MCDPT may stimulate pancreatic cancer cells contributing to pancreatic tumour progression [34–40].

Published data from Esposito et al. [41] showed that mononuclear inflammatory cells of the nonspecific immune response are recruited in pancreatic cancer tissues and they are able to stimulate angiogenesis and cancer progression.

In this pilot study, we have evaluated the correlations between MCDPT, MCAPT, MVD, and EA in a series of 31 PDACP having undergone surgery and our results suggest an association between tryptase and microvascular bed. We found this correlation in double way: first in terms of number of positive tryptase cells and immunostained microvessels and second in terms of extension of positive tryptase area and immunostained microvessels area. To avoid methodological bias the evaluation of MCDPT, MCAPT, MVD, and EA has been performed by means of an image analysis system at ×400 magnifications in a well-defined microscopic area of 0.19 mm2 as previously published in other tumours types [1]. Our preliminary data agree on the biological role of tryptase as a strong proangiogenic factor. In this manner we suggest that tryptase from MCs may play a role also in pancreatic tumour tissue angiogenesis. Further studyin a large series of patients will be necessary to confirm our first results. In this context, the evaluation of MCs positive to tryptase may be a novel surrogate angiogenic marker in pancreatic cancer able to predict angiogenic index. We hypothesize also to stop pancreatic angiogenesis inhibiting mast cell degranulation by means of C-Kit inhibitors or targeting tryptase by means of gabexate mesilate or nafamostat mesilate [42–45]. Further studies in more large series of patients are awaited regarding this very intriguing topic.

Conflict of Interests

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interests.

References

- 1.Ranieri G, Labriola A, Achille G, et al. Microvessel density, mast cell density and thymidine phosphorylase expression in oral squamous carcinoma. International Journal of Oncology. 2002;21(6):1317–1323. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ranieri G, Ammendola M, Patruno R, et al. Tryptase-positive mast cells correlate with angiogenesis in early breast cancer patients. International Journal of Oncology. 2009;35(1):115–120. doi: 10.3892/ijo_00000319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Weidner N, Semple JP, Welch WR, Folkman J. Tumor angiogenesis and metastasis—correlation in invasive breast carcinoma. The New England Journal of Medicine. 1991;324(1):1–8. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199101033240101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kankkunen JP, Harvima IT, Naukkarinen A. Quantitative analysis of tryptase and chymase containing mast cells in benign and malignant breast lesions. International Journal of Cancer. 1997;72(3):385–338. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0215(19970729)72:3<385::aid-ijc1>3.0.co;2-l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Soucek L, Lawlor ER, Soto D, Shchors K, Swigart LB, Evan GI. Mast cells are required for angiogenesis and macroscopic expansion of Myc-induced pancreatic islet tumors. Nature Medicine. 2007;13(10):1211–1218. doi: 10.1038/nm1649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ribatti D, Ranieri G, Nico B, Benagiano V, Crivellato E. Tryptase and chymase are angiogenic in vivo in the chorioallantoic membrane assay. International Journal of Developmental Biology. 2011;55(1):99–102. doi: 10.1387/ijdb.103138dr. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mangia A, Malfettone A, Rossi R, et al. Tissue remodelling in breast cancer: human mast cell tryptase as an initiator of myofibroblast differentiation. Histopathology. 2011;58(7):1096–1106. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2559.2011.03842.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ranieri G, Gadaleta-Caldarola G, Goffredo V, et al. Sorafenib (BAY 43-9006) in hepatocellular carcinoma patients: from discovery to clinical development. Current Medicinal Chemistry. 2012;19(7):938–944. doi: 10.2174/092986712799320736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Goffredo V, Gadaleta CD, Laterza A, Vacca A, Ranieri G. Tryptase serum levels in patients suffering from hepatocellular carcinoma undergoing intra-arterial chemoembolization: possible predictive role of response to treatment. Molecular and Clinical Oncology. 2013;1(2):385–389. doi: 10.3892/mco.2013.59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ranieri G, Passantino L, Patruno R, et al. The dog mast cell tumour as a model to study the relationship between angiogenesis, mast cell density and tumour malignancy. Oncology Reports. 2003;10(5):1189–1193. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Raneri G, Achille G, Florio G, et al. Biological-clinical significance of angiogenesis and mast cell infiltration in squamous cell carcinoma of the oral cavity. Acta Otorhinolaryngologica Italica. 2001;21(3):171–178. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gulubova M, Vlaykova T. Prognostic significance of mast cell number and microvascular density for the survival of patients with primary colorectal cancer. Journal of Gastroenterology and Hepatology. 2009;24(7):1265–1275. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1746.2007.05009.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ammendola M, Sacco R, Sammarco G, et al. Mast cells positive to tryptase and C-Kit receptor expressing cells correlates with angiogenesis in gastric cancer patients surgically treated. Gastroenterology Research and Practice. 2013;2013:5 pages. doi: 10.1155/2013/703163.703163 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ammendola M, Sacco R, Donato G, et al. Mast cell positivity to tryptase correlates with metastatic lymph nodes in gastrointestinal cancer patients treated surgically. Oncology. 2013;85(2):111–116. doi: 10.1159/000351145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ma Y, Ullrich SE. Intratumoral mast cells promote the growth of pancreatic cancer. Oncoimmunology. 2013;1(2) doi: 10.4161/onci.25964.e25964 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ma Y, Hwang RF, Logsdon CD, Ullrich SE. Dynamic mast cell-stromal cell interactions promote growth of pancreatic cancer. Cancer Research. 2013;73(13):3927–3937. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-12-4479. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ranieri G, Grammatica L, Patruno R, et al. A possible role of thymidine phosphorylase expression and5-fluorouracil increased sensitivity in oropharyngeal cancer patients. Journal of Cellular and Molecular Medicine. 2007;11(2):362–368. doi: 10.1111/j.1582-4934.2007.00007.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kondo K, Muramatsu M, Okamoto Y, et al. Expression of chymase-positive cells in gastric cancer and its correlation with the angiogenesis. Journal of Surgical Oncology. 2006;93(1):36–42. doi: 10.1002/jso.20394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ribatti D, Vacca A, Nico B, et al. Bone marrow angiogenesis and mast cell density increase simultaneously with progression of human multiple myeloma. British Journal of Cancer. 1999;79(3-4):451–455. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6690070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tuna B, Yorukoglu K, Unlu M, Mungan MU, Kirkali Z. Association of mast cells with microvessel density in renal cell carcinomas. European Urology. 2006;50(3):530–534. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2005.12.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Galli SJ. Mast cells and basophils. Current Opinion in Hematology. 2000;1(7):32–39. doi: 10.1097/00062752-200001000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Qu Z, Liebler JM, Powers MR, et al. Mast cells are a major source of basic fibroblast growth factor in chronic inflammation and cutaneous hemangioma. American Journal of Pathology. 1995;147(3):564–573. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Grützkau A, Krüger-Krasagakes S, Kögel H, Möller A, Lippert U, Henz BM. Detection of intracellular interleukin-8 in human mast cells: flow cytometry as a guide for immunoelectron microscopy. Journal of Histochemistry and Cytochemistry. 1997;45(7):935–945. doi: 10.1177/002215549704500703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Thomas PS, Pennington DW, Schreck RE, Levine TM, Lazarus SC. Authentic 17 kDa tumour necrosis factor α is synthesized and released by canine mast cells and up-regulated by stem cell factor. Clinical and Experimental Allergy. 1996;26(6):710–718. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sörbo J, Jakobsson A, Norrby K. Mast-cell histamine is angiogenic through receptors for histamine1 and histamine2. International Journal of Experimental Pathology. 1994;75(1):43–50. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Blair RJ, Meng H, Marchese MJ, et al. Human mast cells stimulate vascular tube formation. Tryptase is a novel, potent angiogenic factor. Journal of Clinical Investigation. 1997;99(11):2691–2700. doi: 10.1172/JCI119458. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Grützkau A, Krüger-Krasagakes S, Baumeister H, et al. Synthesis, storage, and release of vascular endothelial growth factor/vascular permeability factor (VEGF/VPF) by human mast cells: implications for the biological significance of VEGF206. Molecular Biology of the Cell. 1998;9(4):875–884. doi: 10.1091/mbc.9.4.875. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wang X, Chen X, Fang J, Yang C. Overexpression of both VEGF-A and VEGF-C in gastric cancer correlates with prognosis, and silencing of both is effective to inhibit cancer growth. International Journal of Clinical and Experimental Pathology. 2013;6(4):586–597. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zhao Y, Wu K, Cai K, et al. Increased numbers of gastric-infiltrating mast cells and regulatory T cells are associated with tumor stage in gastric adenocarcinoma patients. Oncology Letters. 2012;4(4):755–758. doi: 10.3892/ol.2012.830. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mukherjee S, Bandyopadhyay G, Dutta C, Bhattacharya A, Karmakar R, Barui G. Evaluation of endoscopic biopsy in gastric lesions with a special reference to the significance of mast cell density. Indian Journal of Pathology and Microbiology. 2009;52(1):20–24. doi: 10.4103/0377-4929.44956. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ammendola M, Zuccalà V, Patruno R, et al. Tryptase-positive mast cells and angiogenesis in keloids: a new possible post-surgical target for prevention. Updates in Surgery. 2013;65(1):53–57. doi: 10.1007/s13304-012-0183-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Nico B, Mangieri D, Crivellato E, Vacca A, Ribatti D. Mast cells contribute to vasculogenic mimicry in multiple myeloma. Stem Cells and Development. 2008;17(1):19–22. doi: 10.1089/scd.2007.0132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Fajardo I, Pejler G. Human mast cell β-tryptase is a gelatinase. Journal of Immunology. 2003;171(3):1493–1499. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.171.3.1493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Chang DZ, Ma Y, Ji B, et al. Mast cells in tumor microenvironment promotes the in vivo growth of pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. Clinical Cancer Research. 2011;17(22):7015–7023. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-11-0607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Cai S-W, Yang S-Z, Gao J, et al. Prognostic significance of mast cell count following curative resection for pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. Surgery. 2011;149(4):576–584. doi: 10.1016/j.surg.2010.10.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Tod J, Jenei V, Thomas G, Fine D. Tumor-stromal interactions in pancreatic cancer. Pancreatology. 2013;13(1):1–7. doi: 10.1016/j.pan.2012.11.311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Strouch MJ, Cheon EC, Salabat MR, et al. Crosstalk between mast cells and pancreatic cancer cells contributes to pancreatic tumor progression. Clinical Cancer Research. 2010;16(8):2257–2265. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-09-1230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Strouch MJ, Cheon EC, Salabat MR, et al. Crosstalk between mast cells and pancreatic cancer cells contributes to pancreatic tumor progression. Clinical Cancer Research. 2010;16(8):2257–2265. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-09-1230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Protti MP, De Monte L. Immune infiltrates as predictive markers of survival in pancreatic cancer patients. Frontiers in Physiology. 2013;4article 210 doi: 10.3389/fphys.2013.00210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Evans A, Costello E. The role of inflammatory cells in fostering pancreatic cancer cell growth and invasion. Frontiers in Physiology. 2012;3, article 270 doi: 10.3389/fphys.2012.00270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Esposito I, Menicagli M, Funel N, et al. Inflammatory cells contribute to the generation of an angiogenic phenotype in pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. Journal of Clinical Pathology. 2004;57(6):630–636. doi: 10.1136/jcp.2003.014498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Erba F, Fiorucci L, Pascarella S, Menegatti E, Ascenzi P, Ascoli F. Selective inhibition of human mast cell tryptase by gabexate mesylate, an antiproteinase drug. Biochemical Pharmacology. 2001;61(3):271–276. doi: 10.1016/s0006-2952(00)00550-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Mori S, Itoh Y, Shinohata R, Sendo T, Oishi R, Nishibiro M. Nafamostat mesilate is an extremely potent inhibitor of human tryptase. Journal of Pharmacological Sciences. 2003;92(4):420–423. doi: 10.1254/jphs.92.420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Humbert M, Castéran N, Letard S, et al. Masitinib combined with standard gemcitabine chemotherapy: in vitro and in vivo studies in human pancreatic tumour cell lines and ectopic mouse model. PLoS ONE. 2010;5(3) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0009430.e9430 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Marech I, Patruno R, Zizzo N, et al. Masitinib (AB1010), from canine tumou model to human clinical development: where we are? Critical Reviews in Oncology/Hematology. 2013;S1040-8428(13):00266–00267. doi: 10.1016/j.critrevonc.2013.12.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]