Abstract

Background

In prior clinical studies of patients with long QT syndrome (LQTS), pregnancy was associated with fewer cardiac events (CEs) compared to before or after pregnancy. In recent animal studies involving rabbits with LQTS mutations, progesterone had favorable effects on CEs compared to estrogen. The effect of oral contraceptive therapy with its high progesterone/estrogen ratio on the risk of CEs in LQTS patients has not been examined.

Objective

To study the effect of oral contraceptive use on the risk of CEs in LQTS patients.

Methods

We studied 174 patients from the Rochester-based LQTS Registry who responded to a questionnaire about their oral contraceptive use. We used time-dependent Cox regression to estimate the hazard ratio for recurrent CEs when patients were taking versus not taking oral contraceptives during nonpregnancy periods. For this recurrent events analysis, the Prentice-Williams-Peterson (PWP) model was used, and the time origin was defined as the onset of menarche. We adjusted for the baseline QTc interval, history of CEs prior to menarche, age at menarche onset, number of births, time-dependent β- blocker therapy and LQTS genotype.

Results

No differences in the risk of CEs for the times LQTS patients were using versus not using oral contraceptives was found in the general LQTS population (hazard ratio=1.01, p=0.95) or in analyses of LQTS subsets (p>0.2).

Conclusions

Oral contraceptive therapy use did not affect LQTS-related CEs in the study population. Oral contraceptives did not show beneficial or harmful effects in this patient group.

Keywords: Long QT Syndrome, Oral contraceptive therapy, sex hormones, progesterone, estrogen, cardiac events, IKs channels, IKr channels, pregnancy

Introduction

The Inherited long QT syndrome (LQTS) is a genetic cardiac channelopathy caused by ion-channel mutations. These mutations result in delayed ventricular repolarization and are detected by a prolonged QT-interval on the electrocardiogram (ECG). Symptoms in LQTS are known as cardiac events (CEs) and include syncope, aborted cardiac arrest, and sudden cardiac death. In LQT genotype 1 (LQT1) and LQT genotype 2 (LQT2), the delayed rectifier potassium-channels are affected. Mutations in KCNQ1 gene, encoding for the slow component of cardiac K+ channel (IKs), result in LQT1 1,2, and mutation in the KCNH2 gene, encoding for the rapid component of cardiac K+ channel (IKr), result in LQT2 3,4. Earlier studies in LQTS found that pregnancy was not associated with cardiac events in probands or firstdegree relatives 5 and was associated with a significant reduction of cardiac events when compared to the time before first conception 5,6. Pregnancy correlates with a high progesterone/estrogen ratio suggesting a protective role for progesterone in this disorder. Similarly, a few in vivo and in vitro studies have examined the effect of sex hormones on the IKs and IKr potassium ion-channel currents with consistent findings suggesting that estrogen may cause QT-interval prolongation while progesterone does not 7-11.

Hormonal therapy studies in females with LQTS are limited. This study is the first to examine the effects of oral contraceptive therapy on the risk of cardiac events in female patients with LQTS. We compared cardiac events between patients who are and are not receiving oral contraceptive therapy to evaluate the effect of this hormonal therapy on the clinical course of patients with LQTS. The results of this study provide new information regarding oral contraceptive medications with their high progesterone/estrogen ratio and also address safety concerns that might be associated with oral contraceptive use in patients with LQTS.

Methods

Study population

This study included patients from the Rochester-based Long QT Syndrome Registry who responded to a questionnaire about their oral contraceptive use (n=175). Study packages were mailed to eligible patients in September 2010 (n=340). Questionnaires were sent out to female patients who met the following criteria: 1) born between1950 and 1992, with the starting date to reflect the time when OC medications use became popular and the 1992 year limit to ensure that patients who received the questionnaire were at least 18 years of age; 2) genotype positive for LQT1 or LQT2, or clinically diagnosed with QTc interval ≥ 450 msec and are identified clinically as LQTS in the Registry; and 3) who are alive and consent to the study. One patient with missing age at menarche (time-origin for the analysis) was excluded. The total number of patients included in the study was 174.

This study was approved by the University of Rochester Medical Center Research Subjects Review Board.

Time origin and follow-up

The time origin was selected as the date of menarche to restrict cardiac event counts to a time period when oral contraceptive use was a likely possibility and to preclude controls (i.e. patients who are not taking oral contraceptives) from coming from pre-menarche time periods. Follow-up time during pregnancy periods was excluded by temporarily removing pregnant subjects from the risk set for two reasons: 1) patients are usually free of oral contraceptive use during pregnancy, and 2) the risk of cardiac events during pregnancy has been shown to be low, possibly due to the hormonal changes during pregnancy 5,6. Follow-up was censored at age 40 to minimize the confounding influence of other cardiovascular diseases and hormonal changes after this age.

End points

The study end point was the occurrence of one or more syncopal events or aborted cardiac arrest (ACA), i.e., first and recurrent events after the onset of menarche. No deaths occurred in this study population during follow-up as a consequence of the retrospective design.

Statistical analysis

We compared patients who responded to the questionnaire versus those who did not respond using the Wilcoxon test for continuous variables and the chi-squared test for categorical variables. The clinical characteristics of the study population were summarized by the mean ± SD for continuous variables and by frequencies and proportions for categorical variables. Analysis of the primary end point was based on the conditional PWP non-gap-time model (Prentice, Williams, and Peterson, 1981), an extension of the stratified Cox model 12 allowing for time-dependent strata with separate nonparametric baseline hazard functions for each recurrent event. The PWP model was used to estimate the hazard ratio for recurrent cardiac events (first and subsequent) for patients on versus off oral contraceptive therapy after the onset of menarche. Oral contraceptive use was modeled as a time-dependent variable to account for the changing status of oral contraceptive use (being on to going off and vice versa). The hazard ratio was adjusted for the history of cardiac events prior to menarche, baseline QT interval corrected for heart rate (QTc), age at menarche onset, number of births and a time-dependent variable for β-blocker use to adjust for LQTS therapy.

All statistical tests were two-sided 0.05 level tests. Analyses were carried out with SAS software (version 9.3, SAS institute, Cary, North Carolina).

Results

Baseline Clinical Characteristics

Patients who responded to the oral contraceptive questionnaire (n=175) were compared to those who did not respond (n=165) as shown in Table 1. Comparison of both groups showed no significant differences in variables relevant to LQTS severity including family history, baseline QTc interval measurements and non-pharmacological therapy. For non-responders, we have no information about specific variables requested by this questionnaire such as age at menarche and onset of oral contraceptive use, and therefore we were unable to compare these variables.

Table 1. Clinical characteristics of female LQTS patients who received the oral contraceptive questionnaire according to their response.

| Clinical Characteristics | Responded | Did not Respond | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Demographics: | |||

| Number of Patients, # | 175 | 165 | |

| Genetics: | |||

| Genotyped Positive | 130(87*) | 108(93 *) | 0.09 |

| LQT1 | 62(35) | 55(33) | 0.68 |

| LQT2 | 66(38) | 50(30) | 0.15 |

| LQT3 | 0(0) | 1(1) | 0.49 |

| Family History (sudden cardiac death before age 40) | 42(24) | 40(24) | 0.96 |

| ECG: | |||

| QTc-interval value (msec)† | 492±45 | 498±61 | 0.95 |

| Non-pharmacological Therapy: | |||

| Left cervico-thoracic sympathetic denervation (LCSD) | 7(4) | 3(2) | 0.34 |

| Pacemaker | 23(13) | 23(14) | 0.83 |

| Implantable Cardioverter Defibrillator (ICD) | 54(31) | 68(41) | 0.05 |

Values are Mean ± SD where indicated. Numbers in parentheses are percent (%).

Percent of those who were tested (n=150)

First measurements recorded in LQTS Registry.

Clinical characteristics for the study population, patients who responded to the questionnaire and included in this study (n=174; one patient was missing age at menarche), are presented in Table 2. There were 129 genotype-positive patients, 20 genotype-negative patients, and 25 patients with unknown information about their genotype. There were 62 patients genotype positive for LQT1 and 65 patients genotype positive for LQT2, one patient has LQT4, and one patient was genotyped positive for both LQT10 and LQT11. Only 18 (14%) patients had cardiac events prior to menarche, while 41 (24%) patients had a family history of sudden cardiac death. The average baseline QTc interval was 492 msec, and it ranged from 380 to 670 msec. Of all 174 patients, included in the study, those who reported oral contraceptive (OC) use at any time are (n=147), compared to those who never used OC (n=27).

Table 2. Clinical Characteristics of study population.

| Clinical Characteristics (n=174)* | |

|---|---|

| Demographics: | |

| Age at menarche (year) | 12.5± 2 |

| Year of birth | 1973± 9 |

| Genetics: | |

| Genotype positive | 129(74) |

| - LQT1 | 62(36) |

| - LQT2 | 65(37) |

| - LQT4 | 1(0.57) |

| - LQT10/LQT11 | 1(0.57) |

| Genotype negative for known mutations | 20(12) |

| Genotype missing (not tested) | 25(14) |

| History: | |

| Patients with cardiac events prior to menarche | 18(14) |

| Family History: Sudden cardiac death before age 40 | 41(24) |

| ECG: | |

| QTc-interval value (msec)† | 492±45 |

| Number of births | 2 ± 2 |

| Oral contraceptive use at any time | 147 |

| Generation of first oral contraceptive used: | |

| 1st generation | 27(18) |

| 2nd generation | 18(12) |

| 3rd generation | 41(28) |

| 4th generation | 8(5) |

| Unknown | 53(36) |

Values are Mean ± SD where indicated. Numbers in parentheses are percent (%).

First measurements recorded in LQTS Registry.

Multivariate time-dependent analyses

Long QT syndrome in the general study population

The results of the covariate-adjusted PWP model for recurrent cardiac events in female LQTS patients are shown in Table 3. The hazard ratio is reported relative to going off oral contraceptive medications. There is no difference in the risk of cardiac events (syncope or aborted cardiac arrest) for the times LQTS patients were using versus not using oral contraceptives (Hazard ratio=1.01, (0.71, 1.44), p=0.95). The hazard ratios are adjusted for baseline QTc interval, cardiac events prior to menarche, age at menarche onset, number of births, LQT1 (versus LQT2) genotype and time-dependent β-blocker use.

Table 3. Adjusted hazard ratio* for recurrent cardiac events† in LQTS females comparing oral contraceptive use to no oral contraceptive use during follow-up.

| Parameter | Hazard ratio | (95% CI) | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Time-dependent oral contraceptive use | 1.01 | 0.71– 1.44 | 0.95 |

| Time-dependent β-blockers use | 0.36 | 0.24-0.54 | <0.0001 |

Abbreviations: CI denotes confidence interval

Adjusted for time-dependent β-blockers use, cardiac events prior to menarche, QTc interval, age at menarche, number of births, LQTS genotypes. See Methods for details.

Total recurrent cardiac events, in the 174 patients studied, including syncope or aborted cardiac arrest = 268.

LQTS subset analyses model

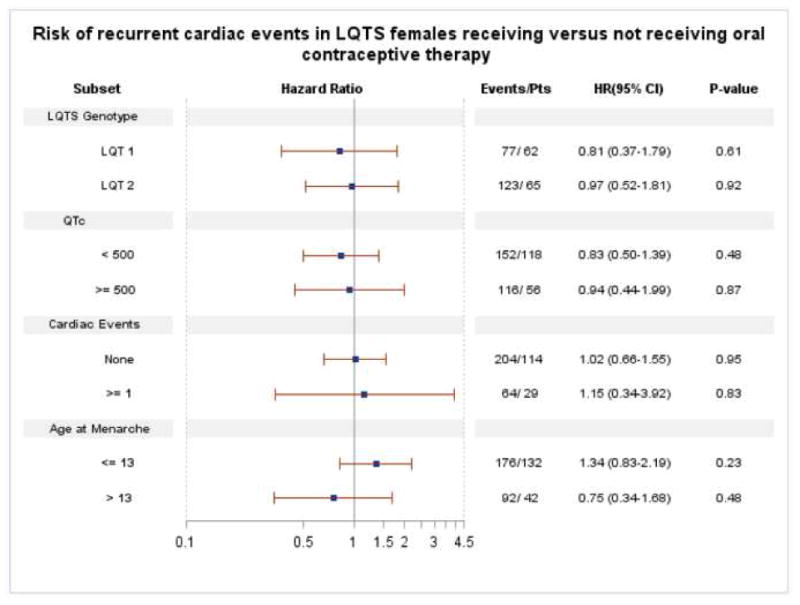

Hazard ratios for oral contraceptive use from covariate-adjusted PWP models for recurrent cardiac events in several LQTS subsets are shown in Figure 1. No effect of oral contraceptive use on the risk of recurrent cardiac events was seen in any of the subsets analyzed (p>0.2 for every subset).

Figure 1. Relative risk of recurrent cardiac events in LQTS females using versus not using Oral contraceptive therapy in different LQTS subsets.

Abbreviations: LQTS: Long QT syndrome; LQT1: LQTS genotype 1; LQT2: LQTS genotype2; Events: total number of recurrent cardiac events (syncope or aborted cardiac arrest) at the end of follow-up; Pts: number of patients; QTc: first measurement recorded in LQTS Registry; Cardiac events: reflects the occurrence of cardiac events prior to menarche, HR: adjusted hazard ratios for variables described in the text, see Methods for more details; CI: confidence interval.

Discussion

In this study we examined the effect of oral contraceptive medications use in females who have LQTS, a genetic disease caused by mutations in the cardiac ion-channels. We found that oral contraceptive medication use was not associated with either a decreased or an increased risk for cardiac events in the overall LQTS female patients, nor in any of the analyzed LQTS subgroups who were followed between the onset of menarche up to until age 40.

In earlier clinical LQTS studies, it was found that the clinical course of LQTS patients is influenced by age 13-15, gender 16, pregnancy, and post-partum status in females 5,6. During childhood, LQTS males have higher risk for first cardiac events 16 and serious events 15 compared to females. After puberty, the risk for cardiac events in females is increased compared to a decreased risk in males 14. In prior clinical LQTS studies, pregnancy was not associated with cardiac events in probands or first-degree relatives 5. Moreover it was associated with a significant reduction of cardiac events when compared to the time before first conception (hazard ratio (HR) =0.28) 6. However, during the 9-month post-partum interval, this risk for cardiac events was increased significantly (HR= 2.7) 6 and almost returns to its pre-pregnancy state after that 9-month post-partum period (HR=0.91) 5,6. Changes in the risk for cardiac events following puberty and during pregnancy and post-partum periods are correlated with hormonal changes in females, and these clinical observations suggest that female sex hormones might play an important role in the clinical course of patients with LQTS.

A few in-vivo and in-vitro studies that have examined the role of sex hormones in cardiac ionchannels, mainly the wild-type (normal) IKs and IKr channels led to consistent findings suggesting that estrogen may cause QT-interval prolongation while progesterone does not 7-10. Drici et al. 7 found that 17β-estradiol or E2, the bioactive form of estrogen, down-regulates IKs expression in the heart of ovariectomized female rabbits. Progesterone was found to enhance IKs depolarization in guinea pig hearts in a study by Nakamura et al. 8. The former study suggests that estrogen may contribute to or exacerbate QT-interval prolongation, while the Nakamura study suggests that progesterone may be beneficial in patients with QT prolongation. Other hormonal studies in the wild type IKs currents in guinea pig hearts 9 and in human embryonic kidney-293 cells (HEK-cells) 9,10 found that physiological levels of E2 acutely blocked IKr current, again suggesting that estrogen may have a prolonging effect on the QT-interval. Studies in mutant IKs (KCNQ1) and IKr (KCNH2) channels, corresponding to LQT1 and LQT2 respectively, are limited. A recently published study by Odening et al. 11 found that transgenic LQT2 ovariectomized rabbits treated with estradiol had major cardiac events when compared to rabbits treated with progesterone. Findings from the Odening et al. study 11 suggested that mutant IKr (KCNH2) channels do respond similarly to sex hormones as do the wild type IKr channels, with estrogen increasing the risk for cardiac events compared to progesterone.

The use of oral contraceptive medications represents a therapeutic model with high content of sex hormones, mainly progesterone and estrogen. Clinical studies were necessary to evaluate the effect of using this hormonal therapy on patients with LQTS. We collected information from patients enrolled in the Rochester-based LQTS registry about their history of oral contraceptive use and compared the risk of cardiac events between the times they were on versus off the therapy. We expected to see a protective effect among LQTS patients who were on oral contraceptive therapy.

Our study results are not consistent with the animal studies that suggested a protective role for progesterone. One of many reasons for the discrepancy could be that the pathways by which these hormones affect cardiac repolarization in the cardiac ion-channels are different among different species, i.e., between rabbits, guinea pigs, and humans. For example, in the Drici et al. study of the wild-type IKs ion-channel in rabbits 7, the wild-type IKs m-RNA was down-regulated when treated with estrogen (genomic pathway). In the Nakamura et al. study 8, progesterone was thought to enhance the IKs current in guinea pig ventricular myocytes through nitric oxide, a non-genomic pathway. Similarly, in the Kurokawa et al. study in guinea pigs 9, the acute effects on IKr that were observed were independent of estrogen receptors; i.e. a non-genomic pathway.

Another reason for not seeing any changes in LQTS clinical course for patients during oral contraceptive therapy might be a result of the current concentrations of sex hormones (progesterone and estrogen) found in this hormonal therapy for humans. We think that much higher concentrations of both hormones are actually needed to observe any effect either protective (progesterone) or harmful (estrogen). In fact, the side-effects of both hormones were found to be dose-dependent 17, and oral contraceptive medications are optimized to contain minimal hormonal concentrations of progesterone and estrogen that are high enough to achieve inhibitory effects on ovulation without causing unwanted side-effects. The observed reduction of cardiac events in LQTS during pregnancy 5,6 correlates with high concentrations of progesterone and estrogen that are achieved physiologically during pregnancy 18. Progesterone blood concentration during pregnancy is 10-15 times higher than that achieved using progestin containing oral contraceptive medications which is about 9.2 ng/mL 19. This concentration of progestin in oral contraceptives is not very much higher than progesterone concentration during the normal menstrual cycle (∼3.5 ng/mL) 19. Similarly, progesterone levels used in Odening et al. study were comparable to progesterone concentrations in pregnant rabbits 11. Therefore, the effect of sex-hormones on the potassium cardiac ionchannels currents (IKs and IKr) needs further exploration. Studies might include different LQTS disease models to investigate new therapeutic pathways that alter the chemical structure of progesterone to optimize its shortening effect on QTc-interval without having its original endocrine effects, approaches that should provide better insight for observations in hormonal studies clinically.

On the other hand, the use of oral contraceptive therapy in LQTS females followed in our study was not associated with higher risk for cardiac events. The IKr channel, also known as human Ether-a-go-go Related Gene channel (hERG), is known to be a main target for a variety of structurally different drugs that inhibit its K+ current and lead to drug-induced QT-interval prolongation 20-22. LQTS patients, in general, are more sensitive to drug-induced QT prolongation 23,24. Many medications known to block the hERG channel are not recommended for use in LQTS patients. In our study, oral contraceptive use appears to be safe in LQTS patients overall. More specifically, since the 95% confidence interval for the hazard ratio for oral contraceptive use is (0.71, 1.44), conditional on the below-mentioned limitations, we can conclude with 95% confidence that this therapy does not increase the risk of syncope or aborted cardiac arrest by more than 44% –and most likely closer to 1%, given that the hazard ratio was 1.01. It is important to note that different patients can respond differently to different forms of oral contraceptive therapy, and the availability of various oral contraceptive regimens and medications allows selection of the most appropriate therapy for the individual patient based on its tolerable side effects. Long QT syndrome patients are generally at a higher risk for drug-induced QT-prolongation, and any therapy should be monitored closely to determine its effect on the clinical course of the disease. In fact, a recent study found that healthy females taking fourth-generation oral contraceptive therapy, which is based on anti-androgenic progestin forms, had a significantly longer QTc than women who were not on any oral contraceptive therapy and women taking earlier oral contraceptive formulations (first, second and third generation forms) 25. In our study, of those whose first oral contraceptive was known, less than 9% were using fourth generation oral contraceptive medications, suggesting that even more attention should be given to LQTS patients using this generation of oral contraceptive medications.

Lack of randomization in comparing oral contraceptive use between patients represents the most important factor of concern in this study, but simultaneously randomizing patients to use oral contraceptive therapy is not ethically feasible, so we attempted to adjust for potential bias by using appropriate statistical analyses in this observational study. Similar to other studies based on questionnaires, those who responded to the questionnaire might represent a lower risk group of LQTS patients since high-risk patients may not respond to the questionnaire due to disease morbidity. Indeed, since patients had to survive long enough to answer the questionnaire, any potential effects on mortality could not be evaluated in this retrospective study of survivors. We did a comparison between responders and non-responders to the questionnaire, and it showed no significant differences in LQTS disease severity in the two groups. Accordingly, we consider our study to represent a reasonably unbiased sample for oral contraceptive use in LQTS. However, the relatively small number of patients included in the study might limit our ability to detect a real difference (n=174). But study power for time-to-event analyses depends on the number of events, and the strength of dependence between them, and not just the total number of patients. In this study there were 268 recurrent cardiac events, and it is unlikely that low power was a reason for the absence of positive or negative risk findings in LQTS patients taking oral contraceptives.

Conclusion

In summary, female LQTS patients using oral contraceptive therapy are not at a lower or higher risk for cardiac events compared to those not using this therapy. Overall, we believe that oral contraceptive medications have no beneficial or harmful effects in LQTS patients. This study is the first to explore the effect of this hormonal therapy in female patients with LQTS, and additional investigations of sex hormones in long QT syndrome using other hormonal therapies is indicated.

Acknowledgments

Disclosure: The project described in this publication was supported in part by: 1) the University of Rochester CTSA award number TL1 RR024135 from the National Center for Research Resources and the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences of the National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD; and 2) Research grants HL-33843 and HL-51618 from the National Heart Lung and Blood Institute of the National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD. The authors have reported that they have no relationships to disclose. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Abbreviations

- ACA

aborted cardiac arrest

- CEs

cardiac events

- LQTS

Long QT Syndrome

- LQT1

Long QT Syndrome genotype 1

- LQT2

Long QT Syndrome genotype 2

- LQTS Registry

Long QT Syndrome Registry

- SCD

sudden cardiac death

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Keating M, Atkinson D, Dunn C, Timothy K, Vincent GM, Leppert M. Linkage of a cardiac arrhythmia, the long QT syndrome, and the harvey ras-1 gene. Science. 1991;5006:704–706. doi: 10.1126/science.1673802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Keating M, Dunn C, Atkinson D, Timothy K, Vincent GM, Leppert M. Consistent linkage of the long- QT syndrome to the harvey ras-1 locus on chromosome 11. Am J Hum Genet. 1991;6:1335–1339. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Curran ME, Splawski I, Timothy KW, Vincent GM, Green ED, Keating MT. A molecular basis for cardiac arrhythmia: HERG mutations cause long QT syndrome. Cell. 1995;5:795–803. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90358-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sanguinetti MC, Jiang C, Curran ME, Keating MT. A mechanistic link between an inherited and an acquired cardiac arrhythmia: HERG encodes the IKr potassium channel. Cell. 1995;2:299–307. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90340-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rashba EJ, Zareba W, Moss AJ, Hall WJ, Robinson J, Locati EH, Schwartz PJ, Andrews M. Influence of pregnancy on the risk for cardiac events in patients with hereditary long QT syndrome. LQTS investigators. Circulation. 1998;5:451–456. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.97.5.451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Seth R, Moss AJ, McNitt S, et al. Long QT syndrome and pregnancy. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2007;10:1092–1098. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2006.09.054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Drici MD, Burklow TR, Haridasse V, Glazer RI, Woosley RL. Sex hormones prolong the QT interval and downregulate potassium channel expression in the rabbit heart. Circulation. 1996;6:1471–1474. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.94.6.1471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nakamura H, Kurokawa J, Bai CX, Asada K, Xu J, Oren RV, Zhu ZI, Clancy CE, Isobe M, Furukawa T. Progesterone regulates cardiac repolarization through a nongenomic pathway: An in vitro patch-clamp and computational modeling study. Circulation. 2007;25:2913–2922. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.702407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kurokawa J, Tamagawa M, Harada N, Honda S, Bai CX, Nakaya H, Furukawa T. Acute effects of oestrogen on the guinea pig and human IKr channels and drug-induced prolongation of cardiac repolarization. J Physiol. 2008;12:2961–2973. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2007.150367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ando F, Kuruma A, Kawano S. Synergic effects of beta-estradiol and erythromycin on hERG currents. J Membr Biol. 2011;1:31–38. doi: 10.1007/s00232-011-9360-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Odening KE, Choi BR, Liu GX, Hartmann K, Ziv O, Chaves L, Schofield L, Centracchio J, Zehender M, Peng X, Brunner M, Koren G. Estradiol promotes sudden cardiac death in transgenic long QT type 2 rabbits while progesterone is protective. Heart Rhythm. 2012;5:823–832. doi: 10.1016/j.hrthm.2012.01.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cox D. Regression models and life tables (with discussion) J R Stat Soc B. 1972;34:187–220. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hobbs JB, Peterson DR, Moss AJ, et al. Risk of aborted cardiac arrest or sudden cardiac death during adolescence in the long-QT syndrome. JAMA. 2006;10:1249–1254. doi: 10.1001/jama.296.10.1249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sauer AJ, Moss AJ, McNitt S, et al. Long QT syndrome in adults. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2007;3:329–337. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2006.08.057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Goldenberg I, Moss AJ, Peterson DR, et al. Risk factors for aborted cardiac arrest and sudden cardiac death in children with the congenital long-QT syndrome. Circulation. 2008;17:2184–2191. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.701243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Locati EH, Zareba W, Moss AJ, et al. Age- and sex-related differences in clinical manifestations in patients with congenital long-QT syndrome: Findings from the international LQTS registry. Circulation. 1998;22:2237–2244. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.97.22.2237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dhont M. History of oral contraception. Eur J Contracept Reprod Health Care. 2010;15(Suppl 2):S12–8. doi: 10.3109/13625187.2010.513071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hendrick V, Altshuler LL, Suri R. Hormonal changes in the postpartum and implications for postpartum depression. Psychosomatics. 1998;2:93–101. doi: 10.1016/S0033-3182(98)71355-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Norman AW, Litwack G. Estrogens and progestins. In: Norman AW, Litwack G, editors. Hormones. San Diego, CA: Academic Press; 1997. pp. 361–386. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mitcheson JS, Chen J, Lin M, Culberson C, Sanguinetti MC. A structural basis for drug-induced long QT syndrome. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2000;22:12329–12333. doi: 10.1073/pnas.210244497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mitcheson J, Perry M, Stansfeld P, Sanguinetti MC, Witchel H, Hancox J. Structural determinants for high-affinity block of hERG potassium channels. Novartis Found Symp. 2005;266:136–50. discussion 150-8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Perry M, Sanguinetti M, Mitcheson J. Revealing the structural basis of action of hERG potassium channel activators and blockers. J Physiol. 2010;17:3157–3167. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2010.194670. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Donger C, Denjoy I, Berthet M, Neyroud N, Cruaud C, Bennaceur M, Chivoret G, Schwartz K, Coumel P, Guicheney P. KVLQT1 C-terminal missense mutation causes a forme fruste long-QT syndrome. Circulation. 1997;9:2778–2781. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.96.9.2778. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Napolitano C, Schwartz PJ, Brown AM, Ronchetti E, Bianchi L, Pinnavaia A, Acquaro G, Priori SG. Evidence for a cardiac ion channel mutation underlying drug-induced QT prolongation and lifethreatening arrhythmias. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol. 2000;6:691–696. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-8167.2000.tb00033.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sedlak T, Shufelt C, Iribarren C, Lyon LL, Bairey Merz CN. Oral contraceptive use and the ECG: Evidence of an adverse QT effect on corrected QT interval. Annals of Noninvasive Electrocardiology. 2013;4:389–98. doi: 10.1111/anec.12050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]