Abstract

Purpose

Most studies of night eating syndrome (NES) fail to control for binge eating, despite moderate overlap between the two conditions. Establishing the independent clinical significance of NES is imperative for it to be considered worthy of clinical attention. We compared students with and without NES on eating disorder symptomatology, quality of life, and mental health, while exploring the role of binge eating in associations.

Methods

Students (N=1636) ages 18 to 26 (M=20.9) recruited from ten U.S. universities completed an online survey including the Night Eating Questionnaire (NEQ), Eating Disorder Examination-Questionnaire (EDE-Q), Project Eating Among Teens, and the Health-Related Quality of Life-4. NES was diagnosed according to endorsement of proposed diagnostic criteria on the NEQ. Groups (NES vs. non-NES) were compared on all dependent variables and stratified by binge eating status in secondary analyses.

Results

The prevalence of NES in our sample was 4.2%; it was 2.9% after excluding those with binge eating. Body mass index did not differ between groups, but students with NES were significantly more likely to have histories of underweight and anorexia nervosa. In students with NES, EDE-Q scores were significantly higher; purging, laxative use, and compulsive exercise were more frequent; quality of life was reduced; and histories of depression, attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder, and self-injury were more common. Binge eating did not account for all of these differences; the presence of it and NES was associated with additive risk for psychopathology on some items.

Conclusions

NES may be a distinct clinical entity from other DSM-5 eating disorders.

Keywords: eating disorders, night eating syndrome, night eating, binge eating, university students

Introduction

Night eating syndrome (NES) is a disorder characterized by evening hyperphagia and nocturnal ingestions (Figure 1), in addition to sleep and mood disturbances. Associations between NES, eating disorder (ED) behaviors and attitudes, poor physical and psychosocial functioning, and maladaptive coping have been found.1–9 In one study,10 young adults had a higher prevalence of evening hyperphagia than any other age group. Further, university students who report high stress,11 inconsistent sleep patterns,12 and disordered eating13 may be at particular risk for developing NES symptoms. The prevalence of NES using proposed diagnostic criteria14 was reported as 5.7% in one university sample,4 yet few studies have comprehensively explored the significance of night eating in this group.

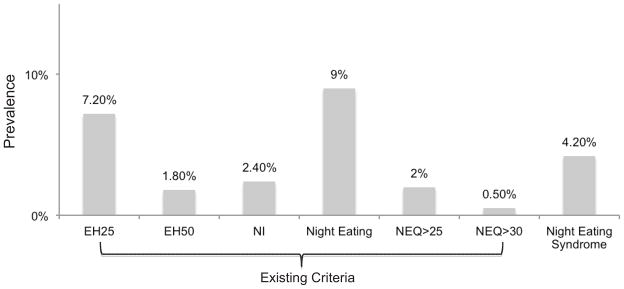

Figure 1.

Prevalence of Night Eating and Night Eating Syndrome (NES) Diagnosed With Existing or Proposed Criteria

Abbreviations/definitions not defined elsewhere: EH25, evening hyperphagia, defined as eating >25% of daily caloric intake after suppertime; EH50, evening hyperphagia, defined as eating >50% of daily caloric intake after suppertime; NI, nocturnal ingestions, defined as waking up from sleep and eating “about half the time”; Night Eating, defined as either evening hyperphagia (25% cutoff) or nocturnal ingestions; NEQ>25, score >25 on the NEQ; NEQ>30, score >30 on the NEQ.

Night eating syndrome was diagnosed using proposed criteria,14 which can be viewed in Table 1.

Absent from most NES research is concurrent attention to the presence of binge eating, despite moderate overlap between the two behaviors.14,15 It is not yet clear whether night eating alone is associated with eating attitudes and psychosocial health, or whether binge eating explains previously reported findings. NES is now categorized in the DSM-516 and standardized diagnostic criteria have been developed,14 two developments that may promote further research on this question.

Historically, studies of NES have struggled to achieve large enough samples to interpret results reliably. Here, we take advantage of a large university-based sample to compare ED attitudes and behaviors, quality of life (QOL), and indicators of mental health between students with and without NES, preliminarily exploring the role of binge eating in associations of interest. We hypothesized that students with NES would report more ED pathology, poorer QOL, and would be more likely to have a self-reported psychiatric history compared with students without NES. In secondary analyses we compared weight and ED history, ED behaviors, and maladaptive behaviors between groups. Finally, we report separate prevalence estimates of NES in this sample determined from proposed and existing criteria in the literature.

Method

Data were obtained from a cross-sectional online study, The Stanford Athletic Training and Health: Lifestyle and Eating Tendencies in University Students (ATHLETICS) study, which examined eating, exercise, and health among students recruited from ten U.S. universities in 2008. Inclusion criteria were: (a) age between 18 and 26, (b) academic affiliation, and (c) Internet access. All students were recruited via a social networking site (SNS) through targeted advertisements and (at the home study site, Stanford) via campus listserves. Athletes identified on any publicly available team roster were oversampled in the parent study by sending them a personal message through the SNS with study information. After informed consent was obtained, eligible participants were directed to the full 295-item survey. The Stanford University Panel of Medical Research in Human Subjects and the National Collegiate Athletic Association approved all data collection protocols.

Although a traditionally-defined response rate cannot be reliably calculated for online surveys, data on “hits” to the website showed that the online consent form was viewed 3,339 times and that 1,688 participants completed the survey, resulting in a 50.6% proxy “response rate.” Fifty-one participants were excluded from analyses for: (a) failure to meet inclusion criteria (n=21); (b) nonexistent or very incomplete responses (n=18); (c) duplicate entries (n=5); or (d) disclosure of untruthful responses (n=8). In total, 1,636 students were included in analyses.

Measures

Demographics and weight history were reported. We calculated current body mass index (BMI; kg/m2). BMI was also calculated at reported highest and lowest weights achieved at their current height to determine a history of underweight (BMI<18.5) or overweight (BMI≥25) as defined by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC).17

Several established measures of disordered eating and QOL were included in the survey. NES was assessed with the Night Eating Questionnaire (NEQ)18 using a clinical cut score of ≥ 25 for broad assessment and ≥ 30 for increased specificity. The NEQ was also used to diagnose NES following proposed research criteria14 as detailed in Table 1. The Eating Disorder Examination-Questionnaire (EDE-Q)19 measured ED behaviors and attitudes; it contains a global score and four subscales: restraint, eating concern, weight concern, and shape concern. QOL was determined by the CDC Health-Related QOL-4 (HRQOL),20 which yields an index of unhealthy days in the past month (max=30) due to poor physical or mental health and a report of the number of days that poor health prevented engagement in usual activities. Selected questions from the Project Eating Among Teens Survey (EAT-II)21 were included to determine the presence of diet pill use in the last month, self-reported lifetime history of an ED, and frequency of current substance use in the last year. Substance use variables were coded to reflect either “frequent” (> weekly) or “infrequent” (< weekly) use. Presence of binge drinking (≥ 5 drinks per session) in the last month was also assessed. Participants were asked if they had ever been diagnosed with depression, anxiety, attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), or any other psychiatric disorder, and reported on psychotropic medication usage in the past year. Finally, history of self-injury regardless of intent was assessed.

Table 1.

Criteria and Algorithm for Diagnosing Night Eating Syndrome (NES) in Our Sample

| NES Proposed Criteria Night Eating Questionnaire (NEQ) Question (Item Number) |

NEQ Scores Coded as Present for Symptom (Scale 0–4) |

|---|---|

|

| |

| A. The daily pattern of eating demonstrates a significantly increased intake in the evening and/or nighttime, as manifested by one or both of the following: | |

| 1. At least 25% of food intake is consumed after the evening meal | |

| How much of your daily food intake do you consume after suppertime? (5) | 3 (51–75%,) or 4 (76–100%, almost all) |

| 2. At least two episodes of nocturnal eating per week | |

| Other than only to use the bathroom, how often do you wake up at least once in the middle of the night? (9) | 3 (more than once a week) or 4 (every night) on item 9 and 2 (about half the time), 3 (usually), or 4 (always) on item 12 |

| When you get up in the middle of the night, how often do you snack? (12) | |

| B. Awareness and recall of evening and nocturnal eating episodes are present | |

| When you snack in the middle of the night, how aware are you of your eating? (13) | 1 (a little), 2 (somewhat), 3 (very much so), or 4 (completely) |

| C. The clinical picture is characterized by at least three of the following features: | |

| 1. Lack of desire to eat in the morning and/or breakfast is omitted on four or more mornings per week | |

| How hungry are you usually in the morning? (1) | 0 (not at all), 1 (a little), or 2 (somewhat) on item 1 or 2 (12:01 to 3pm), 3 (3:01 to 6pm), or 4 (6:01 or later) on item 2 |

| When do you usually eat for the first time? (2) | |

| 2. Presence of a strong urge to eat between dinner and sleep onset and/or during the night | |

| Do you have cravings or urges to eat snacks after supper, but before bedtime? (3) | 3 (very much so) or 4 (extremely so) on either item 3 or 4 |

| Do you have cravings or urges to eat snacks when you wake up at night? (4) | |

| 3. Sleep onset and/or sleep maintenance insomnia are present four or more nights per week | |

| How often do you have trouble getting to sleep? (8) | 2 (about half the time), 3 (usually), or 4 (always) on item 8 or 4 (every night) on item 9 |

| Other than only to use the bathroom, how often do you get up at least once in the middle of the night? (9) | |

| 4. Presence of a belief that one must eat in order to initiate or return to sleep | |

| Do you need to eat in order to get back to sleep when you awake at night? (11) | 1 (a little), 2 (somewhat), 3 (very much so), or 4 (extremely so) |

| 5. Mood is frequently depressed and/or mood worsens in the evening | |

| Are you currently blue or down in the dumps? (6) | 3 (very much so) or 4 (extremely so) on item 6 or 3 (early evening) or 4 (late evening/nighttime) on item 7 |

| When you are feeling blue, is your mood lower in the: [scale listed] (7) | |

| D. The disorder is associated with significant distress and/or impairment in functioning | |

| N/A (NEQ does not assess this criterion) | N/A |

| E. The disordered pattern of eating is maintained for at least 3 months | |

| How long have your current difficulties with night eating been going on? (15) | 3 months or more |

| F. The disorder is not secondary to substance abuse or dependence, medical disorder, medication, or another psychiatric disorder. | |

| N/A (unable to assess) | N/A |

Recurrent Binge Eating

Binge eating was considered present in participants who reported objective binge eating by DSM-516 criteria. Objective and subjective binge eating behaviors are both characterized by a sense of loss of control over eating, but they differ in the amount of food consumed. Objective binge episodes involve the consumption of an objectively large amount of food, whereas subjective episodes involve a “normal” or small amount. Recurrent binge eating (BE) was defined as objective binge eating ≥ four times in the last month, consistent with DSM-5 core criteria for bulimia nervosa (BN) and binge eating disorder (BED).16 Participants with anorexia nervosa (AN) were included.

Data Analysis

In primary analyses, the independent variable was dichotomous reflecting whether participants met criteria for NES. Primary dependent variables included EDE-Q and HRQOL scores and psychiatric history. Secondary analyses examined weight history, ED behaviors, ED history, previous medication use, substance use, and self-injury. Data were non-normally distributed and homoscedastic; thus, hypothesis testing included χ2 or Fisher’s Exact Test for categorical dependent variables and Mann-Whitney U testing for continuous dependent variables.

Because individuals with NES reported more binge eating in the past month than individuals without NES (4.4 episodes vs. 1.4, p<0.001), and night eating and binge eating frequently coexist,14,15 we performed exploratory analyses, stratifying groups by BE status. This post-hoc testing was conducted to explore whether observed differences were due to BE and any additive associations resulting from combined BE and NES. For these analyses the predictor variable was categorical reflecting the following four groups: a) NES-only, b) BE-only c) NES/BE and d) controls (students without NES or BE). We conducted χ2 and one-way ANOVA testing. Planned orthogonal comparisons using χ2 or Fisher’s Exact Test and Mann-Whitney U testing explored differences between the (a) NES-only and control groups and the (b) BE-only and NES/BE groups. We did not control for lifetime depression because the BE-only and NES-only groups did not differ on this variable (p=0.15). Finally, we used regression testing to explore competitive athlete status as a covariate in all above associations.

We corrected for possible Type I error using the Hochberg-modified Bonferroni method applied to each family of tests. All analyses were two-tailed with an initial alpha level of 0.05. Analyses were performed using SPSS v18.0 for MacIntosh (Chicago, IL).

Results

A total of 1,636 university students aged 18 to 26 years (M=20.9, SD=1.7) were analyzed (Tables 2 and 3). The majority were female (59.5%), Caucasian (74.2%), and at the undergraduate level (91.5%). Mean BMI was 23.3 (SD=3.4) kg/m2. Competitive athletes comprised 59.6% (n=975) of the sample. Sixty-seven participants (4.2%) met proposed diagnostic criteria for NES. Figure 1 presents this prevalence of NES against the prevalence of NES defined using past criteria. Importantly, 80.6% (n=54) of those meeting proposed criteria for NES failed to meet the previously published NEQ screening cut-off of 25.

Table 2.

Characteristics of the Overall Dataset and Comparison of Demographics Between Groups (NESa and non-NES)

| Total Group (N=1636) | NES (n=67) | non-NES (n=1569) | Analysis | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Demographics | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | U | z | p |

|

|

|||||||||

| Age (years) | 20.9 | 1.7 | 20.9 | 1.4 | 20.9 | 1.7 | 48348.5 | −.42 | 0.68 |

|

|

|||||||||

| n | % | n | % | n | % | χ2 | df | p | |

|

|

|||||||||

| Female | 972 | 59.5 | 42 | 62.7 | 908 | 59.7 | .25 | 1 | 0.71 |

| Education status | |||||||||

| Undergraduate student | 1491 | 91.5 | 62 | 92.5 | 1387 | 91.3 | .394 | 3 | 0.95 |

| Graduate student | 88 | 5.4 | 3 | 4.5 | 84 | 5.5 | |||

| Post-graduate | 34 | 2.1 | 1 | 1.5 | 33 | 2.2 | |||

| Other | 17 | 1.0 | 1 | 1.5 | 16 | 1.1 | |||

| Race/Ethnicity | |||||||||

| Caucasian | 1202 | 74.2 | 52 | 77.6 | 1123 | 74.3 | 1.76 | 7 | 0.98 |

| Asian | 166 | 10.2 | 5 | 7.5 | 156 | 10.3 | |||

| Hispanic/Latino | 94 | 5.8 | 4 | 6.0 | 87 | 5.8 | |||

| Black/African American | 81 | 5.0 | 4 | 6.0 | 74 | 4.9 | |||

| American Indian/Alaskan Native | 5 | 0.3 | 0 | 0.0 | 4 | 0.3 | |||

| Native Hawaiian/Other Pacific Islander | 2 | 0.1 | 0 | 0.0 | 2 | 0.1 | |||

| Biracial or Multiracial | 53 | 3.3 | 2 | 3.0 | 50 | 3.3 | |||

| Other | 17 | 1.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 16 | 1.1 | |||

|

|

|||||||||

| Weight History | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | U | z | p |

|

|

|||||||||

| Body mass index (BMI; kg/m2) | 23.3 | 3.4 | 23.6 | 4.1 | 23.3 | 3.4 | 49396.0 | −.26 | 0.80 |

|

|

|||||||||

| Weight categoryb | n | % | n | % | n | % | χ2 | df | p |

|

|

|||||||||

| Underweight | 41 | 2.6 | 3 | 4.5 | 38 | 2.5 | 1.13 | 2 | 0.57 |

| Normal weight | 1167 | 73.7 | 47 | 70.1 | 1109 | 73.8 | |||

| Overweight | 376 | 23.7 | 17 | 25.4 | 355 | 23.6 | |||

| History of underweight (BMI<18.5) | 215 | 13.6 | 19 | 28.4 | 195 | 13.0 | 12.76 | 1 | 0.001* |

| History of overweight (BMI≥25) | 588 | 37.3 | 28 | 42.4 | 556 | 37.2 | 0.73 | 1 | 0.44 |

Table 3.

Comparison of Eating Disorder Symptomatology and Psychosocial Health Between Groups (NES and non-NES)

| Total Sample (N=1636) | NES (n=67) | non-NES (n=1569) | Test of Differences | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| EDE-Q | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | U | z | p |

|

|

|||||||||

| Restraint | 1.40 | 1.41 | 2.19 | 1.79 | 1.37 | 1.38 | 36798.0 | −3.61 | <0.001* |

| Eating | 0.65 | 1.05 | 1.53 | 1.56 | 0.61 | 1.01 | 30289.5 | −5.81 | <0.001* |

| Shape | 1.91 | 1.55 | 3.16 | 1.86 | 1.86 | 1.52 | 28178.0 | −5.45 | <0.001* |

| Weight | 1.53 | 1.49 | 2.79 | 1.80 | 1.48 | 1.45 | 28964.0 | −5.65 | <0.001* |

| Global | 1.36 | 1.23 | 2.41 | 1.60 | 1.32 | 1.19 | 27112.5 | −5.27 | <0.001* |

|

|

|||||||||

| ED behaviors (# episodes/28) | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | U | z | p |

|

|

|||||||||

| Binge eating | 1.5 | 4.1 | 4.4 | 8.3 | 1.4 | 3.7 | 35585.5 | −5.03 | <0.001* |

| Purging | 0.3 | 2.3 | 1.5 | 6.7 | 0.2 | 1.5 | 46084.0 | −3.65 | <0.001* |

| Laxative use | 0.1 | 0.5 | 0.2 | 0.9 | 0.05 | 0.5 | 47284.5 | −3.61 | <0.001* |

| Diet pill use (n, %) | 43 | 2.6 | 6 | 9.0 | 37 | 2.4 | 10.40 | 1 | 0.008 |

| Exercise for weight/shape | 2.3 | 5.4 | 4.9 | 7.7 | 2.2 | 5.3 | 38222.0 | −4.34 | <0.001* |

|

|

|||||||||

| ED diagnosis (lifetime) | n | % | n | % | n | % | χ2 | df | p |

|

|

|||||||||

| Diagnoseda,b | 60 | 3.8 | 9 | 13.6 | 50 | 3.3 | 18.37 | 1 | 0.001* |

| Diagnosed/Undiagnoseda,c | 261 | 16 | 26 | 38.8 | 233 | 15.3 | 26.04 | 1 | <0.001* |

| ANa | 39 | 2.4 | 9 | 13.4 | 30 | 2.0 | 35.28 | 1 | <0.001* |

| BNa | 28 | 1.7 | 5 | 7.5 | 22 | 1.4 | 13.94 | 1 | 0.004 |

| BEDa | 11 | 0.7 | 3 | 4.5 | 8 | 0.5 | 14.60 | 1 | 0.009 |

| EDNOSa | 18 | 1.1 | 2 | 3.0 | 16 | 1.0 | 2.15 | 1 | 0.18 |

|

|

|||||||||

| HRQOL (# days/30) | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | U | z | p |

|

|

|||||||||

| Total unhealthy days (Physical or mental) | 9.0 | 8.2 | 14.0 | 10.5 | 8.0 | 8.9 | 30400.0 | −4.93 | <0.001* |

| Activity limitation due to poor health | 2.5 | 4.9 | 5.9 | 7.5 | 2.4 | 4.7 | 32070.5 | −4.75 | <0.001* |

|

|

|||||||||

| Psychiatric diagnoses (lifetime) | n | % | n | % | n | % | χ2 | df | p |

|

|

|||||||||

| Any diagnosisa | 346 | 21.5 | 26 | 39.4 | 288 | 19.2 | 16.00 | 1 | <0.001* |

| Depressiona | 168 | 10.7 | 17 | 25.8 | 151 | 10.1 | 16.16 | 1 | <0.001* |

| Anxietya | 114 | 7.2 | 11 | 16.4 | 103 | 6.9 | 8.60 | 1 | 0.007 |

| ADHDa | 85 | 5.4 | 12 | 17.9 | 73 | 4.9 | 21.10 | 1 | <0.001* |

| Psychotropic use (last year) | 295 | 18.5 | 20 | 29.9 | 275 | 18.0 | 5.94 | 1 | 0.03 |

| SSRI | 85 | 5.3 | 7 | 10.4 | 78 | 5.1 | 3.61 | 1 | 0.09 |

| Insomnia medication | 28 | 1.8 | 3 | 4.5 | 25 | 1.6 | 2.99 | 1 | 0.11 |

| ADHD medication | 86 | 5.4 | 9 | 13.4 | 77 | 5.0 | 8.83 | 1 | 0.003* |

| Self-injury (lifetime) | 158 | 10.0 | 14 | 20.9 | 143 | 9.5 | 9.20 | 1 | 0.006* |

| Drug use (≥1x/wk, past year) | |||||||||

| Binge drink | 850 | 53.7 | 47 | 70.1 | 800 | 53.0 | 7.55 | 1 | 0.006* |

| Alcohol | 645 | 40.8 | 37 | 55.2 | 606 | 40.2 | 5.98 | 1 | 0.02 |

| Cigarette/Tobacco | 69 | 4.4 | 5 | 7.6 | 63 | 4.2 | 1.71 | 1 | 0.21 |

| Marijuana | 47 | 3.0 | 2 | 3.0 | 45 | 3.0 | 0.000 | 1 | 0.99 |

| Other | 8 | 0.5 | 0 | 0.0 | 7 | 0.5 | 0.309 | 1 | 0.99 |

Abbreviations: EDE-Q, eating disorder examination-questionnaire; AN, anorexia nervosa; BN, bulimia nervosa; BED, binge eating disorder; EDNOS, eating-disorder not otherwise specified; ED, eating disorder; HRQOL, health-related quality of life; ADHD, attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder; SSRI, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor.

Diagnosis based on self-report.

Positive responses to the question, “Have you been diagnosed with an eating disorder?”

Positive responses to the above question or positive responses to the question, “If you have not been diagnosed with an eating disorder, do you feel you have had an eating disorder?”

Statistically significant after applying Hochberg modified Bonferroni to guard against Type I Error.

There were no significant differences between NES and non-NES groups in age, gender, ethnicity, or BMI (Table 2). Those with NES were significantly more likely to have a history of underweight but not overweight, and less likely to have been a competitive athlete in the last year (41.8% vs. 60.6%, χ2=9.49, df=1, p= 0.003).

Significantly more ED symptomatology was present in individuals with NES as indexed by higher scores on all subscales of the EDE-Q and a higher frequency of ED behaviors in the last month (Table 3). The prevalence of a self-reported history of AN was higher in the NES group. Individuals with NES had significantly more impaired QOL and were more likely to report having been diagnosed with a psychiatric disorder in their lifetimes and have used ADHD medication in the last year. They were more likely to have a history of self-injury and binge drinking, but were not more likely to use tobacco or other drugs. All significant results retained their significance when controlling for competitive athlete status in exploratory regression testing.

The Role of Recurrent Binge Eating

BE was endorsed by 222 participants (14.3%) on the EDE-Q. Two of these participants had missing NEQ data and were not included in analyses. Of the 67 NES participants, 22 (32.8%) also met criteria for BE (NES/BE group=1.4% of total sample), whereas 45 (67.2%) did not (NES-only group=2.9% of total sample). A total of 198 participants (12.8%) met criteria for BE but not NES (BE-only group). The remaining participants (n=1278, 82.8%) did not meet criteria for NES or BE (control group).

The dependent variables significantly associated with NES status in prior testing (Table 3) remained significant in exploratory analyses comparing BE and NES categories (Table 4). Results of orthogonal comparisons showed that NES-only students fared significantly worse than controls on most clinical measures. The NES/BE group was significantly more likely to have a history of underweight, higher scores on the EDE-Q weight concern subscale, and more days of activity limitation due to poor health in the last month than the BE-only group even when controlling for competitive athlete status. Descriptively, results suggest the possibility of associated incremental risk to ED pathology and poor mental health with the combined presence of BE and NES.

Table 4.

Chi-Square and ANOVA Results and Planned Post-hoc Comparisons Between NES subgroups (NES-only and NES/BE) and Controls on Eating Disorder Symptomatology and Psychosocial Health Variables

| NES-only (n=45) | BE-only (n=198) | NES/BE (n=22) | Control (n=1278) | Test of Differences (df=3) | Planned Comparisons | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||||||||

| n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | χ2 | p | (ad) | (bc) | |

| History of underweight (BMI<18.5) | 10 | 22.2 | 29 | 15.2 | 9 | 40.9 | 163 | 12.9 | 17.29 | 0.001* | 0.075 | 0.006* |

|

|

||||||||||||

| EDE-Q3 | Mean3 | SD3 | Mean3 | SD3 | Mean3 | SD3 | Mean3 | SD3 | ANOVA | p3 | 33 | |

|

|

||||||||||||

| Restraint | 1.81 | 1.69 | 2.50 | 1.52 | 2.93 | 1.79 | 1.20 | 1.28 | 145.69 | <0.001* | 0.04 | 0.29 |

| Eating | 1.04 | 1.21 | 1.86 | 1.45 | 2.53 | 1.72 | 0.42 | 0.77 | 295.71 | <0.001* | 0.001* | 0.09 |

| Shape | 2.69 | 1.91 | 3.44 | 1.49 | 4.17 | 1.28 | 1.62 | 1.37 | 235.88 | <0.001* | 0.001* | 0.05 |

| Weight | 2.34 | 1.81 | 2.98 | 1.52 | 3.79 | 1.36 | 1.25 | 1.29 | 232.78 | <0.001* | 0.001* | 0.02* |

| Global | 1.99 | 1.55 | 2.69 | 1.31 | 3.39 | 1.30 | 1.12 | 1.03 | 247.95 | <0.001* | 0.001* | 0.04 |

| ED behaviors (# days/28) | ||||||||||||

| Binge eating | 0.5 | 1.0 | 9.0 | 6.0 | 12.4 | 10.6 | 0.2 | 0.7 | 946.80 | <0.001* | 0.02 | 0.17 |

| Purging | 0.1 | 0.3 | 1.1 | 4.7 | 4.4 | 11.4 | 0.09 | 0.8 | 65.14 | <0.001* | 0.05 | 0.09 |

| Laxative use | 0.09 | 0.4 | 0.2 | 1.2 | 0.5 | 1.4 | 0.02 | 0.3 | 79.11 | <0.001* | 0.002* | 0.37 |

| Exercise for weight/shape | 4.6 | 8.4 | 5.1 | 7.2 | 5.5 | 6.3 | 1.8 | 4.7 | 105.15 | <0.001* | 0.001* | 0.51 |

|

|

||||||||||||

| ED diagnosis (lifetime) | n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | χ2 | p | ||

|

|

||||||||||||

| Diagnoseda,b | 5 | 11.4 | 17 | 8.8 | 4 | 18.2 | 32 | 2.6 | 37.57 | <0.001* | 0.008 | 0.25 |

| Diagnosed/Undiagnoseda,c | 12 | 26.7 | 73 | 36.9 | 14 | 63.6 | 153 | 12.0 | 118.51 | <0.001* | 0.01 | 0.03 |

| ANa | 5 | 11.1 | 10 | 5.1 | 4 | 18.2 | 19 | 1.5 | 47.25 | <0.001* | 0.002* | 0.04 |

|

|

||||||||||||

| HRQOL (# days/30) | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | ANOVA | p | ||

|

|

||||||||||||

| Total unhealthy days (Physical or mental) | 13.5 | 11.0 | 12.2 | 10.0 | 15.0 | 9.7 | 7.4 | 8.6 | 75.79 | <0.001* | 0.001* | 0.17 |

| Activity limitation due to poor health | 4.5 | 6.1 | 3.7 | 5.6 | 8.7 | 9.2 | 2.2 | 4.5 | 59.30 | <0.001* | 0.004* | 0.005* |

|

|

||||||||||||

| Psychiatric diagnoses | n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | χ2 | p | ||

|

|

||||||||||||

| Any diagnosisa | 20 | 45.5 | 53 | 27.2 | 6 | 27.3 | 221 | 17.6 | 29.14 | <0.001* | 0.001* | 0.99 |

| Depressiona | 12 | 27.3 | 34 | 17.6 | 5 | 22.7 | 110 | 8.7 | 30.87 | <0.001* | 0.001* | 0.57 |

| ADHDa | 9 | 20.0 | 9 | 4.7 | 3 | 13.6 | 59 | 4.7 | 23.54 | <0.001* | 0.001* | 0.12 |

| ADHD medication (last yr) | 6 | 13.3 | 9 | 4.5 | 3 | 13.6 | 62 | 4.8 | 9.74 | 0.03 | 0.02 | 0.11 |

| Self-injury | 10 | 22.2 | 24 | 12.4 | 4 | 18.2 | 113 | 8.9 | 12.00 | 0.007* | 0.008* | 0.50 |

| Binge drink | 30 | 66.7 | 101 | 51.8 | 17 | 77.3 | 667 | 52.6 | 8.73 | 0.04 | 0.07 | 0.03 |

In planned comparisons, a=NES-only, b=BE-only, c=NES/BE, and d=Control

Abbreviations: EDE-Q, eating disorder examination-questionnaire; AN, anorexia nervosa; ED, eating disorder. HRQOL, health-related quality of life. ADHD, Attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder

Lifetime diagnosis based on self-report.

Positive responses to the question, “Have you been diagnosed with an eating disorder?”

Positive responses to the above question or positive responses to the question, “If you have not been diagnosed with an eating disorder, do you feel you have had an eating disorder?”

Statistically significant after applying Hochberg modified Bonferroni to guard against Type I Error.

Discussion

This is one of the largest studies of NES in university students conducted to date, and among the first to explore incremental associations of BE and NES on ED psychopathology and mental health. Individuals with NES reported more ED symptoms, mental health problems, self-injurious behavior, and poorer QOL than controls. Our findings add to the growing body of literature suggesting that NES may be a distinct syndrome of clinical significance associated with ED pathology and psychosocial impairment. Night eating and BE appear to show separate and potentially additive risk for psychopathology in some clinically relevant variables.

About 4% of our student sample met proposed criteria14 for NES. Although NES was diagnosed using a self-report measure, this prevalence is similar to that found by Nolan et al.4 (5.7%) in which NES was diagnosed by both survey and semi-structured interview,18 using the same diagnostic criteria. In our study, a third of those individuals meeting criteria for NES also reported recurrent BE, reducing the prevalence of ‘pure’ NES to 2.9%. This prevalence of NES is slightly higher than that reported in a population-based young adult sample (1.3%) using the same diagnostic criteria and assessment methods,3 suggesting NES may be more common in student populations. However, the fact that few students in our sample reported core symptoms of evening hyperphagia and nocturnal ingestions provides evidence against the general assumption that night eating is developmentally normative in university students.

In reporting prevalence of NES with and without the presence of BE, we attempted to examine night eating in a conservative manner. It is possible that future research will determine that the presence of BED supersedes a diagnosis of NES. Also, some may consider evening hyperphagia, or eating a large amount of food after an evening meal even without loss of control, as a type of binge eating. However, behaviors important to NES often occur in the context of desiring to initiate or resume sleep at night, which has been shown to differentiate NES from BED.22 This night eating typically takes the form of grazing throughout the evening or waking to eat a snack, usually consisting of a few hundred calories, as opposed to consuming objectively large amounts of food in a discrete period of time.23 Designating a diagnosis of NES vs. BED seems more difficult nosologically when nocturnal ingestions are not present and binge episodes are occurring exclusively at night. This ‘evening hyperphagia only’ form of NES needs more research to clarify the function and size of intake at night and during the day, and to characterize patterns and timing of binge episodes when they are present in relation to the night eating.

Similar to other studies,10,24 we observed that the prevalence of NES varied widely (between 0.5% and 9%) depending on the criteria used to diagnose NES. Unexpectedly, the NEQ screening cutoff of 25,18 which diagnosed 2% of our sample with NES, failed to capture nearly 80% of the students meeting proposed criteria. The NEQ was originally designed as a screening measure but current cut-points may be too specific. It is difficult for persons who endorse evening hyperphagia in the absence of nocturnal ingestions to score above 25 on the NEQ.18 Thus, the 2% diagnosed by the NEQ screening cutoff, or those with both evening hyperphagia and nocturnal ingestions, may have a more severe form of NES, and future studies should examine this possibility. Determining cut scores for the Nocturnal Ingestions and Evening Hyperphagia subscales of the NEQ18 may prove more useful than the total score. Larger validation studies are needed to determine the most appropriate screen for NES and to standardize future studies.

We observed no relation between NES and current BMI, a consistent finding in studies of university4 and young adult samples3 but contradictory to some studies of adult populations.24,25 As posited by Striegel-Moore and colleagues,26 the effects of NES on weight may not yet be observed in young adults, with weight changes emerging only over time. Our finding that more students with NES reported a history of underweight and a prior diagnosis of AN, but did not differ from non-NES students in current weight status, suggests greater prior weight gain may have occurred in the NES group, supporting the above hypothesis. This finding seems in contrast to what is observed in other EDs which show a history of weight suppression from previous higher weights27 but may also simply reflect diagnostic cross-over from AN to NES. Although it is important to acknowledge the possibility of recall bias that may impact the accuracy of our weight history data, there may be a correlation between prior caloric restriction and subsequent NES. When more daytime restriction is present, as in AN, physical pressure to eat at night may increase. Once this night eating pattern is established, achievement of a normal weight may not be adequate to correct a habitually delayed pattern of eating. Prospective studies are needed to further investigate causal relationships between NES, dietary restraint, and weight.

Corroborating research in adult samples,3,28 elevated eating, shape, and weight concern, but not dietary restraint, was found in students with NES even when accounting for BE. Higher prevalence of laxative use and driven exercise among students with NES was also observed. The mean EDE-Q scores of students with NES in our sample appear lower than the EDE-Q norms of adult females with AN, BN, and BED;29,30 this observation mirrors the extant empirical literature.3 Students with NES may have less eating pathology than students with other EDs or the EDE-Q may fail to adequately capture the ED symptomatology most pertinent to NES.

Consistent with prior research,7,28,31 NES was associated with reduced QOL and worsened health even after excluding those with BE. Students with NES reported twice the number of days of activity limitation due to poor health than that reported by controls. The degree to which NES impacts daily functioning is not yet clear. Prior studies report that individuals with NES have poor sleep quality,4 and restriction of sleep in controlled studies is known to affect neurocognitive and academic performance negatively.32 It is possible that the reduced QOL associated with NES has consequences in multiple domains.

The higher prevalence of lifetime depression in NES was unsurprising, as this relation is noted in the literature consistently.24,26,28 A novel result that merits further study was the higher prevalence of lifetime ADHD in NES students (20% vs. 4.7%). ADHD and NES may share similar biological and genetic risk factors. Alternatively, ADHD medications can impact sleep negatively and reduce daytime appetite33 with potential for a rebound hunger at night. Thus, the use of stimulants to treat ADHD may lead to night eating symptoms, although symptoms attributable to ADHD would not justify an NES diagnosis. Students with NES did report a higher rate of ADHD medication usage in the year prior to our survey, and future studies should examine current psychotropic medication usage and NES symptoms.

This is the first study to explore and find a relation between NES and self-injury, suggesting that associations with other maladaptive or impulsive behaviors may exist in NES. We did not differentiate between suicidal and non-suicidal self-injury in this survey; additional studies would further our understanding of how NES impacts these complex phenomena. One study34 found that more individuals (aged 15–39 years) with NES had used marijuana and crack cocaine at least once compared with controls, but our study found that the frequent use of these drugs in the last year was no more common in students with NES. Regardless, as with other EDs, providers should be vigilant in screening NES patients for self-injury, alcohol, and drug use.

Clinical Implications

This study reinforces work35,36 indicating that NES may be a distinct clinical entity from BE, as BE did not fully account for the clinical impairment observed in NES students. Because the dual presence of NES and BE was indicative of more severe pathology on some measures, querying for this behavior in individuals with EDs characterized by BE (i.e., BN, BED) may provide information on clinical severity. To determine prognostic significance and inform treatment directions, additional research efforts should identify whether subgroups of other ED patients with night eating have a differential response to treatment. Finally, because a subset of individuals with NES engaged in extreme weight control behavior, studies examining the validity of subtyping NES based on the presence of compensatory behavior are indicated. Such research will further knowledge on the clinical utility and validity of NES and night eating in the DSM, and determine whether tailored interventions for ED patients with night eating are necessary. Verifying the validity of proposed criteria for NES, including frequency thresholds and the duration criterion, is a crucial first step.

Limitations

Although the use of an Internet survey was advantageous in enabling us to collect comprehensive data from ten universities across the U.S., yielding one of the largest sample sizes of NES to date, it includes limitations. As with most online studies, there is a possibility of selection bias, and findings may lack generalizability to the minority of students who are non-SNS users. The parent study oversampled competitive athletes, and this may also impact generalizability, although our results remained significant even after controlling for competitive athlete status. Further, all data were self-reported and we were unable to use structured clinical interviews to confirm diagnoses. We were limited to the NEQ for diagnosing NES and did not inquire about shift work, an exclusion criterion, or distress and/or impairment in functioning related to NES, an obligatory criterion.14 One study3 found that 10% of young adults diagnosed with NES by proposed criteria do not endorse distress or impairment in functioning. Our prevalence of NES may be slightly inflated; however, our reported prevalence of NES is similar to that documented in a study using clinical interview to diagnose NES in a student sample.4 Our use of the EDE-Q to assess objective binge eating may have underestimated the number of participants with BE37 and self-reports of previously diagnosed EDs, heights, or weights could be inaccurate.38 Counterbalancing this limitation, Internet surveys reduce the effects of social desirability39 and increase comfort with responding to questions,40 and our survey assessed truthfulness, perhaps enhancing accuracy and honesty. However, with this cross-sectional study, we were unable to confidently gather complete lifetime weight histories. We also cannot make causal inferences from this study. Finally, despite our large sample size, we still may have lacked adequate power on some analyses to detect differences between groups.

Conclusions

NES is present, but infrequent in a university population. Proposed criteria capture a particular subgroup of individuals with clinically significant ED pathology, psychosocial impairment, and self-injurious behaviors. BE did not account for all differences between groups, and NES seems to have a separate incremental risk for these associations. Health care providers should assess for the presence of night eating in individuals with BE, as the dual existence of these behaviors may signal the presence of greater severity ED and greater impact on daily functioning.

Implications and Contribution.

Most studies of night eating syndrome (NES) fail to control for binge eating (BE). Thus, the independent clinical significance of NES has been unclear. We found that NES is associated with clinical impairment independent of BE, and that the presence of it and BE may be associated with additive risk for psychopathology.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the Stanford Undergraduate Research Program. Dr. Lock received funding from the National Institutes of Health (NIH) K24 mechanism. Dr. Runfola was supported by the NIH grant T32MH076694 and Global Foundation for Eating Disorders (www.gfed.org).

We acknowledge Christopher Fairburn and Dianne Neumark-Szteiner for allowing the use of their measures, and Laura Bachrach, Katherine Bell Hill, Mary Jacobson, Jenny Wilson, Alana Frost Shain, Jennifer Carlson, and the Stanford WEIGHT Lab research assistants for their work in the parent study that provided the initial data collection. We are deeply grateful to the students who participated in the study.

Abbreviations

- ADHD

attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder

- AN

anorexia nervosa

- BE

recurrent binge eating (objective binge eating ≥ four times in the last month)

- BED

binge eating disorder

- BMI

body mass index

- BN

bulimia nervosa

- CDC

Centers of Disease Control and Prevention

- DSM

Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders

- EAT-II

Project Eating Among Teens Survey

- ED

eating disorder

- EDNOS

eating disorder not otherwise specified

- EDE-Q

Eating Disorder Examination-Questionnaire

- HRQOL

Health Related Quality of Life

- NES

night eating syndrome

- NEQ

Night Eating Questionnaire

- QOL

quality of life

- SNS

social networking site

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest/Disclosure Statement: All authors have no financial relationships or conflicts of interest relevant to this article to disclose. Dr. Runfola wrote the initial draft of the manuscript. No honorarium, grant, or other forms of payment were given to anyone to produce the manuscript.

Abstract published in the International Conference for Eating Disorders May 2009 annual meeting conference brochure.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Herpertz-Dahlmann B. Adolescent eating disorders: definitions, symptomatology, epidemiology and comorbidity. Child Adolesc Psychiatr Clin N Am. 2009;18:31–47. doi: 10.1016/j.chc.2008.07.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Vinai P, Allison KC, Cardetti S, et al. Psychopathology and treatment of night eating syndrome: a review. Eat Weight Disord. 2008;13:54–63. doi: 10.1007/BF03327604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fischer S, Meyer AH, Hermann E, et al. Night eating syndrome in young adults: delineation from other eating disorders and clinical significance. Psychiatry Res. 2012;200:494–501. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2012.07.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nolan LJ, Geliebter A. Night eating is associated with emotional and external eating in college students. Eat Behav. 2012;13:202–206. doi: 10.1016/j.eatbeh.2012.02.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wichianson JR, Bughi SA, Unger JB, et al. Perceived stress, coping and night-eating in college students. Stress and Health. 2009;25:235–240. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Quick VM, Byrd-Bredbenner C. Weight regulation practices of young adults. Predictors of restrictive eating. Appetite. 2012;59:425–430. doi: 10.1016/j.appet.2012.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Thompson SH, DeBate RD. An exploratory study of the relationship between night eating syndrome and depression among college students. J Coll Stud Psychotherapy. 2010;24:39–48. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lindeman M, Stark K. Emotional eating and eating disorder psychopathology. Eat Disord. 2001;9:251–259. doi: 10.1080/10640260127552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.van Strien T, Ouwens MA. Effects of distress, alexithymia and impulsivity on eating. Eat Behav. 2007;8:251–257. doi: 10.1016/j.eatbeh.2006.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Striegel-Moore RH, Franko DL, Thompson D, et al. Night eating: prevalence and demographic correlates. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2006;14:139–147. doi: 10.1038/oby.2006.17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cooley E, Toray T, Valdez N, et al. Risk factors for maladaptive eating patterns in college women. Eat Weight Disord. 2007;12:132–139. doi: 10.1007/BF03327640. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lund HG, Reider BD, Whiting AB, et al. Sleep patterns and predictors of disturbed sleep in a large population of college students. J Adolesc Health. 2010;46:124–132. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2009.06.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Delinsky SS, Wilson GT. Weight gain, dietary restraint, and disordered eating in the freshman year of college. Eat Behav. 2008;9:82–90. doi: 10.1016/j.eatbeh.2007.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Allison KC, Lundgren JD, O’Reardon JP, et al. Proposed diagnostic criteria for night eating syndrome. Int J Eat Disord. 2010;43:241–247. doi: 10.1002/eat.20693. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Root TL, Thornton LM, Lindroos AK, et al. Shared and unique genetic and environmental influences on binge eating and night eating: a Swedish twin study. Eat Behav. 2010;11:92–98. doi: 10.1016/j.eatbeh.2009.10.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disroders. 5. Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Publishing; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) [Accessed February 2, 2013.];About BMI for adults. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/healthyweight/assessing/bmi/adult_bmi/index.html.

- 18.Allison KC, Lundgren JD, O’Reardon JP, et al. The Night Eating Questionnaire (NEQ): psychometric properties of a measure of severity of the Night Eating Syndrome. Eat Behav. 2008;9:62–72. doi: 10.1016/j.eatbeh.2007.03.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fairburn CG, Beglin SJ. Assessment of eating disorder psychopathology: interview or self-report questionnaire. Int J Eat Disord. 1994;16:363–370. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) [Accessed February 2, 2013.];Health-Related Quality of Life (HRQOL) Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/hrqol/methods.htm.

- 21.Neumark-Sztainer D, Wall M, Eisenberg ME, et al. Overweight status and weight control behaviors in adolescents: longitudinal and secular trends from 1999 to 2004. Prev Med. 2006;43:52–59. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2006.03.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Vinai P, et al. Presence of a belief that one must eat in order to get to sleep in diagnosing the night eating syndrome. Appetite. doi: 10.1016/j.appet.2013.12.008. in press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Allison KC, Stunkard AJ, Thier SL. Overcoming Night Eating Syndrome: A Step-by-Step Guide to Breaking the Cycle. Oakland, CA: New Harbinger; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 24.de Zwaan M, Roerig DB, Crosby RD, Karaz S, Mitchell JE. Nighttime eating: a descriptive study. Int J Eat Disord. 2006;39:224–232. doi: 10.1002/eat.20246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tholin S, Lindroos A, Tynelius P, et al. Prevalence of night eating in obese and nonobese twins. Obesity. 2009;17:1050–1055. doi: 10.1038/oby.2008.676. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Striegel-Moore RH, Dohm F, Hook JM, et al. Night eating syndrome in young adult women: prevalence and correlates. Int J Eat Disord. 2005;37:200–206. doi: 10.1002/eat.20128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Berner LA, Shaw JA, Witt AA, Lowe MR. The relation of weight suppression and body mass index to symptomatology and treatment response in anorexia nervosa. J Abnorm Psychol. 2013;122:694–708. doi: 10.1037/a0033930. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lundgren JD, Allison KC, O’Reardon JP, et al. A descriptive study of non-obese persons with night eating syndrome and a weight-matched comparison group. Eat Behav. 2008;9:343–351. doi: 10.1016/j.eatbeh.2007.12.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Aardoom JJ, Dingemans AE, Slof Op’t Landt MC, et al. Norms and discriminative validity of the Eating Disorder Examination Questionnarie (EDE-Q) Eat Behav. 2012;13:305–309. doi: 10.1016/j.eatbeh.2012.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Welch E, Birgegård A, Parling T, et al. Eating disorder examination questionnaire and clinical impairment assessment questionnaire: general population and clinical norms for young adult women in Sweden. Behav Res Ther. 2011;49:85–91. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2010.10.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Colles SL, Dixon JB, O’Brien PE. Night eating syndrome and nocturnal snacking: association with obesity, binge eating and psychological distress. Int J Obes (Lond) 2007;31:1722–1730. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0803664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Curcio G, Ferrara M, De Gennaro L. Sleep loss, learning capacity and academic performance. Sleep Med Rev. 2006;10:323–337. doi: 10.1016/j.smrv.2005.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Dopheide JA, Pliszka SR. Attention-deficit-hyperactivity disorder: an update. Pharmacotherapy. 2009;29:656–679. doi: 10.1592/phco.29.6.656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Striegel-Moore RH, Franko DL, Thompson D, et al. Exploring the typology of night eating syndrome. Int J Eat Disord. 2008;41:411–418. doi: 10.1002/eat.20514. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Vander Wal JS. Night eating syndrome: A critical review of the literature. Clin Psych Rev. 2012;32:49–59. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2011.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Stunkard AJ, Allison KC, Geliebter A, et al. Development of criteria for a diagnosis: Lessons from the night eating syndrome. Compr Psychiatry. 2009;50:391–399. doi: 10.1016/j.comppsych.2008.09.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mond JM, Hay PJ, Rodgers B, Owen C, Beumont PJ. Validity of the Eating Disorder Examination Questionnaire (EDE-Q) in screening for eating disorders in community samples. Behav Res Ther. 2004;42(5):551–67. doi: 10.1016/S0005-7967(03)00161-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Larsen JK, Ouwens M, Engels RC, et al. Validity of self-reported weight and height and predictors of weight bias in female college students. Appetite. 2008;50:386–389. doi: 10.1016/j.appet.2007.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Joinson A. Social desirability, anonymity, and Internet-based questionnaires. Behav Res Methods Instrum Comput. 1999;31:433–438. doi: 10.3758/bf03200723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bethlehem J, Biffignandi S. Handbook of Web Surveys. New Jersey: John Wley & Sons; 2012. [Google Scholar]