Abstract

Purpose

We designed and evaluated for feasibility an intervention - Yo Puedo - that addresses social network influences and socioeconomic opportunities in a neighborhood with substantial gang exposure and early childbearing.

Methods

Yo Puedo combined conditional cash transfers for completion of educational and reproductive health wellness goals with life skills sessions, and targeted youth 16 to 21 years old and same-aged members of their social network. We conducted a 2-arm study with social networks randomized to the intervention or a standard services control arm. We evaluated intervention uptake, adherence and safety; and assessed evidence of effects on behavioral outcomes associated with unintended pregnancy and STI risk.

Results

Seventy-two social networks comprised of 162 youth enrolled, with 92% retention over six months. Seventy-two percent of youth randomized to the intervention participated in intervention activities: 53% received at least one CCT payment; and 66% came to at least one life skills session. We found no evidence that cash payments financed illicit or high-risk behavior. At six months, intervention participants, compared to controls, had a lower odds of hanging out on the street frequently (OR = 0.54, p = 0.10) and a lower odds of reporting their close friends had been incarcerated (OR = 0.6, p=0.12). They reported less regular alcohol use (OR = 0.54, p=0.04) and a lower odds of having sex (OR = 0.50, p = 0.04).

Conclusions

The feasibility evaluation of Yo Puedo demonstrated its promise; a larger evaluation of effects on pregnancy and sustained behavioral changes is warranted.

Keywords: Adolescent, Poverty, Adolescent Pregnancy, United States, Intervention Studies, Juvenile Delinquency

Introduction

Pregnancy rates among U.S. teens aged 15 to 19 remain higher than in any developed nation, with adverse health and socioeconomic consequences (1, 2). Although rates over the last decade have declined for all racial/ethnic groups, the decrease remains lowest for Latina teens (3, 4). In California, where one in eight U.S. adolescents reside (5), Latinas have a teen birth rate that is 3.4 times higher than non-Latino whites (6). Likewise, STI rates illustrate similar disparities by race/ethnicity (7).

Youth violence shapes social environments and sexual health in many U.S. urban neighborhoods. Youth violence is the second leading cause of death for Latino male youth aged 10 to 24 (8). Limited socioeconomic opportunities and social marginalization make gang affiliation an attractive and economically viable direction for some youth (9), one that is often embedded intergenerationally within families (10). Furthermore, gang membership may be aligned with culturally-based masculinity norms that can lead to hyper-masculinity among young males (11), thereby increasing sexual risk-taking. In underserved neighborhoods with widespread community violence, the presence of street gangs constitutes a dominant influence on adolescents’ social norms and individual behaviors (12–14). Male gang involvement has been associated with perpetration of partner violence (15), inconsistent condom use, increased number of partners, and sexual concurrency (16–18). Our past research also found that having a male partner in a gang increased pregnancy incidence among teen females (16) and that gang norms promoted partner concurrency and substance use as signs of masculinity (12).

Among U.S. adolescents overall, socioeconomic disparities and poverty at the individual and household levels are associated with teen pregnancy, childbearing and STIs (19). Educational and career aspirations and expectations constitute an important aspect of socioeconomic opportunities. Youth with educational and career aspirations for the future are more likely to abstain from or delay intercourse and to use contraception if sexually active (20). Pregnant teens have been found to have fewer resources for educational and career development than young women delaying childbearing until adulthood and to experience numerous socioeconomic and social obstacles to achieving their educational goals (21). For Latino immigrants, legal and linguistic barriers further limit access to educational and economic opportunities.

The use of financial incentives to promote educational attainment and health-related behaviors has demonstrated success in improving socioeconomic status, educational attainment and child health, particularly in low and middle income countries (22). Traditionally conceived of as a poverty alleviation strategy, more recently, conditional cash transfer (CCT) interventions have used financial incentives to promote school attendance and specific health behaviors as an HIV prevention strategy (23), with positive effects found among adolescents in Malawi (24). Evaluations of Oportunidades, Mexico’s flagship CCT program, revealed that to improve adolescent reproductive health, interventions must target and incentivize youth participation directly (25). Opportunity NYC, modeled after Oportunidadesoffered cash transfers to 2,400 New York City families and youth conditional on completion of educational and health activities. Three-year evaluation data demonstrated few improvements in adolescent health outcomes (26) yet some increases in time spent on academic activities and reductions in substance use, prompting recommendations for a CCT model that addresses mediating influences, including social context, and a more narrow set of health outcomes. A recent World Bank review (27) concluded that CCT effects on health could be further strengthened through greater emphasis on performance rather than participation (e.g., grade improvement vs. school attendance), as demonstrated in contingency management programs that use CCTs as “reinforcers” to reward positive behaviors (e.g., remaining drug free) (28).

Recognizing the need for intervention approaches that extend beyond individual-level behavior change and that address underlying factors that influence reproductive health outcomes, we designed Yo Puedo (“I can”). Yo Puedo combines CCTs tied to completion of educational and reproductive health wellness goals with life skills education and targeted youth 16 to 21 years old and same-aged members of their social network. This paper reports findings from a randomized feasibility study of Yo Puedo that we conducted with youth in San Francisco’s Mission District, a predominantly Latino neighborhood with substantial gang exposure and early childbearing. To ensure that Yo Puedo held promise as a sexual health intervention that would ultimately reduce unintended pregnancy and STI acquisition, this feasibility study was designed as a prelude to a large-scale effectiveness trial. Our primary aims examined: intervention uptake, adherence and acceptability; safety related to distribution of cash payments to youth directly; and changes in close friend group composition and in individual behavioral risks associated with pregnancy and STI outcomes.

Methods

Theoretical basis for Yo Puedo: A combined CCT and life skills intervention

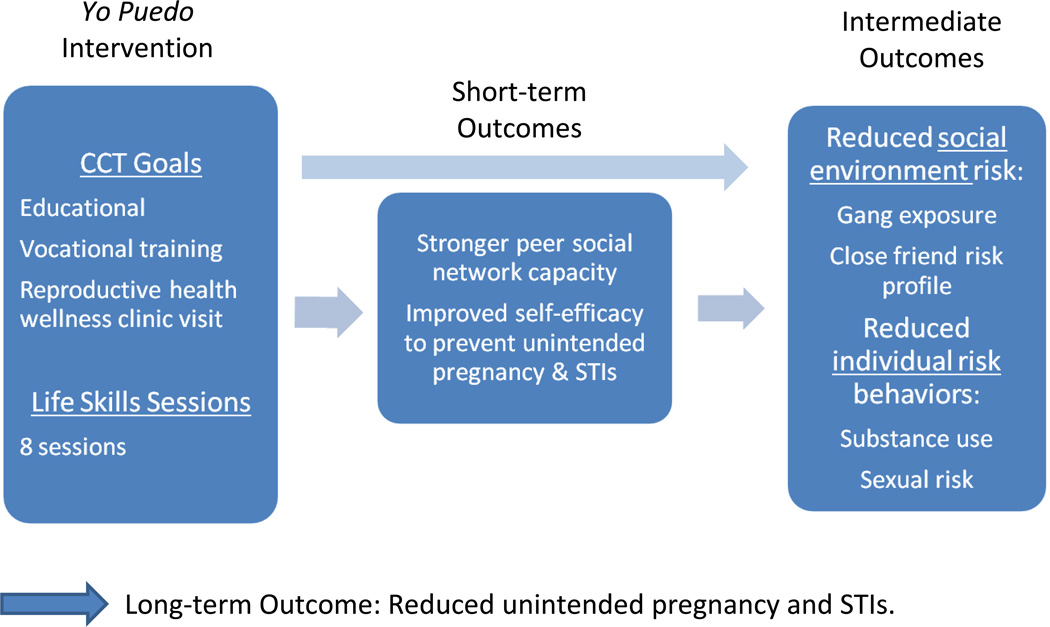

Yo Puedo integrates two intervention models guided by behavioral economics and social learning theory within a social networks framework (see conceptual model, Figure 1). Traditionally, CCT interventions are based on classical microeconomic rational choice theory; however, behavioral economists have adapted this theoretical model to accommodate the recognition that much behavior, including adolescents’ risky sexual behaviors, appear “irrational” but, in fact, follow predictable patterns shaped by adolescents’ cognitive approach to temporal trade-offs and prediction of future preferences (29). Thus, the cash incentives offered, conditional upon completion of educational goals and reproductive health wellness activities, were designed to provide near-term financial and cognitive rewards to encourage youth to shift their time allocation and substitute away from risky behaviors toward actions that support future opportunities. Bandura’s social learning theory (30) addresses cognitive, behavioral, and environmental determinants of health outcomes, and underpins the development of numerous evidence-based reproductive health (31) and gang prevention (32) life skills interventions. Thus, we hypothesized that the CCTs coupled with life skills education would counteract present-oriented time preferences (and encourage present investment in educational and reproductive health activities) and provide positive social support to engage in health promoting behaviors.

Figure 1.

Yo Puedo Conceptual Model

The Yo Puedo Intervention

The Yo Puedo intervention period was six months with an 8-session life skills group offered weekly during the first two months of the intervention period. Multiple social networks were grouped to comprise a single-sex life skills group. Yo Puedo identified 24 participation and performance goals tied to post-secondary education, job training, and reproductive health wellness (e.g., clinic visit) for which small cash payments were made to youth, conditional on documented completion of the given activity (Figure 2). Research on incentives to encourage health promoting behaviors among youth supports use of smaller and more regular incentive payments (33, 34); thus payments ranged from $5–30, depending on the activity. Participants could earn up to $200 through completion of CCTs ($160) and attendance at life skills groups ($5/group).

Figure 2.

Yo Puedo Intervention Components

Through formative research to establish the CCT incentive structure we designated payment amounts for specific educational and reproductive health wellness activities. The formative research involved use of double-bounded contingent valuation methods (35), alongside community partner input, to guide decisions about the appropriate incentive to maximize goal completion while staying within a fixed total budget. Contingent valuation methods (framed as “willingness to accept” the intervention) assessed a respondent’s willingness to complete educational and reproductive health goals at a particular incentive amount. Briefly, participants completed a computer-based interview in which they were asked whether they would be willing to complete a specific goal for a randomly selected amount (the initial offer was randomly selected between $0 and $30). A follow-up question raised the offer to a randomly selected incentive up to $30 if the respondent did not except the first offer, or lowered it to $0 if the respondent accepted the first offer, to minimize incentivizing an activity that would be completed without payment.

The timing of goal completion during the 6-month intervention period was self-paced, and participants were paid monthly for goals completed. We encouraged participants to establish goals to match their current educational needs by selecting from among the list of options provided. Session facilitators provided feedback and information on setting attainable and meaningful goals.

Life skills sessions promoted sexual health with a focus on STI and unintended pregnancy prevention and early-childbearing norms. The sessions emphasized communication and relationship-building skills, improved future orientation through academic achievement and vocational development, and strengthened social networks to utilize community resources and support healthy sexual norms (Figure 2). Skills for Youth created by the Resource Center for Adolescent Pregnancy Prevention of ETR Associates constituted the core curriculum (36), which we adapted to integrate community partner input and to reflect findings from a previous qualitative study we conducted with Mission District Latino adolescents. Trained bilingual, Latina facilitators led the sessions; facilitators were in their early 20s and were the first members of their families to complete a four-year college degree.

Study procedures

Eligible participants were youth aged 16–21 who identified as Latino/-a, resided in San Francisco and frequented the Mission District at least four days per week, spoke English or Spanish, and were not pregnant or parenting. Index participants were asked to recruit up to two friends into their social network who met eligibility criteria, though friends could be of any racial/ethnic background. Index participants were recruited through street, community and school-based outreach strategies. Street-based recruitment followed a modified venue-based recruitment model that built on our past research in this neighborhood (37). Recruitment at community venues helped to ensure recruitment of youth from high-risk social networks in the community and achieved variation in participant characteristics (e.g., nativity; gang affiliation). We established formal partnerships with the two neighborhood high schools and their wellness centers, which permitted direct recruitment of youth at the schools (i.e., school hallways, cafeterias and school yards). For all recruitment, two bilingual, bicultural interviewers approached youth who appeared to be age eligible, conducted a brief screening and, if eligible, described the study. Eligible and interested youth were asked to provide contact information and were given two referral cards to distribute to friends who might want to enroll in Yo Puedo with them. Participants were recruited and enrolled in Yo Puedo during the period June 2011 through January 2012.

Evaluation of Yo Puedo feasibility and effects on behavioral outcomes was conducted through a cluster randomized 2-arm study with social networks randomized to the Yo Puedo intervention or to a control arm that received standard community services. Individuals completed a baseline interviewer-administered questionnaire individually in a private space in one of our community partner agencies or high school wellness centers and again six months after enrollment to coincide with the end of the intervention period. Randomization to the intervention or control group only took place after baseline data collection was complete for all members of the social network so as not to bias self-reported data (both participants and research interviewers were blinded to the assignment). All youth received a guide to youth-friendly services in the community. This constituted the scope of engagement with youth randomized to the control arm. Participants received a $20 cash payment at the end of their baseline visit. Study procedures were approved by the institutional review board at RTI International. Written informed consent/assent was obtained from all participants prior to study enrollment. The IRB granted a waiver of parental consent for minors.

Measures

Feasibility data related to recruitment and randomization of social networks are reported elsewhere (manuscript under review). To assess intervention adherence and acceptability we examined uptake and completion of both CCT-incentivized goals and participation in life skills sessions. To determine whether distributing CCTs to youth directly had adverse effects (an intervention safety concern), we assessed how youth used reward payments. To evaluate preliminary effects of Yo Puedowe examined: 1) childbearing expectations, contraceptive self-efficacy and motivation; and 2) the composition of participants’ close friend group and individual risk behaviors (gang affiliation, substance use, sexual activity). Questions from the National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent Health (Add Health) were used to measure contraceptive self-efficacy and birth control motivations.

Analysis

First, we examined descriptive characteristics of the study population, comparing sociodemographic background and baseline risk profile between intervention and control participants. To ensure randomization balanced these factors between groups we tested for differences using chi-square statistics and t-tests. We conducted standard intent-to-treat analyses for each dichotomous outcome using logistic regression (linear regression for continuous outcomes), with treatment group (intervention vs. control) as the sole predictor in each model (baseline levels did not vary between randomization groups). We adjusted all analyses for clustering at the social network level. In per-protocol analyses, adherent participants were defined as having attended at least three life skills groups and having completed at least one CCT activity for which they received payment. The control group served as the comparison group for the per-protocol analysis. In these multivariable models, we included an indicator for adherent vs. control; the baseline level of the outcome being examined; and three baseline covariates that differed significantly between adherent and control participants: a high-risk close friends measure (gang-involved or detained within past 6 months); a frequent substance use measure (marijuana and/or alcohol at least weekly); and attended middle school in the U.S. We considered any outcomes that differed significantly between intervention and control arms at p<0.1 as providing suggestive evidence of an intervention effect.

Results

Study participant characteristics

Seventy-two social networks comprised of 162 youth enrolled in Yo Puedowith 92% retention over six months. Eligible participants recruited up to two friends who met eligibility criteria; 90% of eligible participants enrolled. Approximately one-third of participants were foreign-born (Table 1), with most of those youth immigrating to the United States after middle school. Most participants were enrolled in school and expressed expectations for post-secondary school education, though 23% reported skipping school on more than four days in the past month. Over two-thirds of youth had ever had vaginal or anal sex; the mean age at first sex was 14.4 years; and one-third of sexually active youth reported unprotected sex in the past six months. Nearly half of participants reported having close friends who were gang-affiliated; 21% drank alcohol at least weekly; and 31% smoked marijuana at least weekly.

Table 1.

Baseline sociodemographic characteristics and risk profile of participants, by randomization group Yo Puedo Feasibility Study, 2011–2012

| Randomization Group |

||

|---|---|---|

| Intervention N = 79 N (%) |

Control N = 83 N (%) |

|

| Sociodemographic Characteristics | ||

| Age | 16.8 | 16.9 |

| Female | 39 (49.37%) | 44 (53.01%) |

| Latino/a | 70 (88.61%) | 69 (83.13%) |

| Foreign-born | 30 (37.97%) | 27 (32.53%) |

| Attended middle school in the U.S. | 53 (67.09%) | 68 (81.93%) |

| Low maternal education (<high school) | 37 (46.84%) | 32 (38.55%) |

| Crowded housing conditions | 38 (48.10%) | 39 (46.99%) |

| Household social service use past 6 months | 47 (59.49%) | 45 (54.22%) |

| Maternal first birth <=18 years | 27 (34.18%) | 22 (26.51%) |

| School and Future Education | ||

| In school now | 72 (91.14%) | 74 (89.16%) |

| Skipped school >4 days in past month | 16 (20.25%) | 22 (26.51%) |

| Educational Expectations | ||

| High School or Equivalent | 10 (12.66%) | 4 (4.82%) |

| Trade School, Vocational School, or Some College | 22 (26.58%) | 19 (22.89%) |

| College Graduate or Beyond | 47 (59.49%) | 60 (72.29%) |

| Relationship and Sexual History | ||

| Sexually active (ever) | 54 (68.35%) | 64 (77.11%) |

| Mean age at first sex (SD) | 14.48 | 14.43 |

| Mean lifetime sexual partnersa | 5.14 | 4.08 |

| Past pregnancya | 8 (14.81%) | 7 (10.94%) |

| Sexual relationships in the past 6 months | ||

| None | 34 (43.04%) | 29 (34.94%) |

| Main only | 22 (27.85%) | 30 (36.14%) |

| Casual only | 16 (20.25%) | 13 (15.66%) |

| Both main and casual | 5 (6.33%) | 11 (13.25%) |

| Contraceptive use in the past 6 monthsb | ||

| Condoms | 37 (84.09%) | 48 (90.57%) |

| Oral contraceptive pills | 13 (29.55%) | 10 (18.87%) |

| Other hormonal method | 10 (22.73%) | 9 (16.98%) |

| Unprotected sex in the past 6 monthsb | 14 (31.82%) | 21 (39.62%) |

| Used emergency contraception past 6 monthsb | 13 (29.55%) | 12 (22.64%) |

| Partner gang affiliatedb | 5 (11.36%) | 8 (15.09%) |

| Partner has concurrent partnersb,c | 12 (27.27%) | 14 (26.42%) |

| Pregnancy Intentions | ||

| Definitely do not want pregnancy in the next 6 months | 73 (92.41%) | 79 (95.18%) |

| Partner definitely does not want pregnancy in next 6 months | 58 (73.42%) | 68 (81.93%) |

| Ideal age for a first child* | 24.65 | 26.27 |

| Accessed reproductive health services in the past 6 months | 37 (46.84%) | 48 (57.83%) |

| Risk Profile | ||

| Gang affiliation | ||

| Individual | 5 (6.33%) | 4 (4.82%) |

| Close friends | 35 (44.30%) | 43 (51.81%) |

| Family | 36 (45.57%) | 49 (59.04%) |

| Close friend incarcerated | 36 (45.57%) | 45 (54.22%) |

| Close friend past pregnancy | 48 (60.76%) | 48 (57.83%) |

| Frequent alcohol use (at least weekly) | 15 (18.99%) | 19 (22.89%) |

| Frequent marijuana use (at least weekly) | 23 (29.11%) | 28 (33.73%) |

p<0.05

Among those who have ever had sex.

Among those who had been sexually active in the past 6 months.

5 individuals were excluded because they did not know if their partner had concurrent partners

Yo Puedo feasibility evaluation

Seventy-two percent of youth randomized to the intervention participated in intervention activities: 53% received at least one CCT payment; and 66% came to at least one life skills group (Table 2). The median amount earned was $30 (range $0–$200). The most commonly completed goals were tutoring, resume, clinic visit, college/career counseling and course credit recovery. Three-quarters of intervention participants who attended three or more sessions reported that they became closer with the friends with whom they enrolled; half made new friends in the groups; and three-quarters discussed session topics with group members outside the intervention sessions. The primary reasons cited for not attending groups included: being too busy (36%); other activities or sports (30%); and laziness (14%). Similar reasons were offered for not completing goals. Participants who were adherent to the intervention in general reported fewer risk behaviors at baseline than those intervention participants who did not participate or participated minimally. A lower proportion of adherent participants had ever had sex (52% vs. 68%, p<0.01); used alcohol frequently (3% vs. 19%, p<0.01); and had gang-affiliated close friends (36% vs. 46%, p<0.05).

Table 2.

Yo Puedo uptake and adherence among intervention participants assessed over six-month intervention period

| Intervention Arm N=79 N (%) |

|

|---|---|

| Lifeskills Sessions | |

| Median number of sessions attended (range) | 2 (0 – 8) |

| Attended at least one session | 52 (66%) |

| Among participants attending 3+ sessions (N=32) | |

| Became closer with friends with whom enrolled | 25 (78%) |

| Made new friends in life skills groups | 15 (47%) |

| Discussed session topics with life skills group members outside of group | 23 (72%) |

| Discussed session topics with friends not enrolled in Yo Puedo | 19 (60%) |

| Goal completion for Conditional Cash Transfer (CCT) payment | |

| Median number of goals completed for CCT (range) | 2 (0 – 14) |

| Completed at least one goal | 42 (53%) |

| Educational/Job goals only | 26 (33%) |

| Reproductive Health goal only | 1 (1%) |

| Both types of goals | 15 (19%) |

| Median CCT amount earned $30 ($0 – $200) | |

| Maximum payment amount earned | 4 (5%) |

| Combined Intervention Adherence | |

| Completed at least one goal and attended 1+ group | 36 (46%) |

| Completed at least one goal and attended 3+ groups | 31 (39%) |

We found no evidence that cash payments financed illicit or high-risk behavior; rather, youth primarily reported they saved the money they earned (53%); used it to purchase food (56%); or spent it shopping (23%). Only two youth reported using money earned to purchase alcohol or drugs. In addition, in de-briefing interviews with community agency and school site staff, no perverse effects of cash payments to youth were reported.

Evidence of intervention effects on intermediate outcomes

Comparison of intermediate outcomes at six-months follow-up revealed some evidence of shifts in the composition of participants’ social group toward lower risk individuals and in individual risk behaviors (Table 3). At follow-up, intervention participants had a lower odds of hanging out on the street corner frequently (OR = 0.54, p = 0.10) and a lower odds of reporting their close friends had been incarcerated or detained (OR = 0.6, p=0.12). They reported less regular alcohol consumption across a categorical measure of use (OR = 0.54, p=0.04), though a non-significant lower odds of frequent alcohol use. At follow-up, individuals randomized to the intervention arm vs. control also reported a lower odds of having sex in the past six months (OR = 0.50, p = 0.04). Contraceptive self-efficacy and motivation was reported to be lower in the intervention group than the control (β=−0.13, p=0.07); though, this was not significant in the per-protocol analysis. In the multivariable per-protocol analysis, adherent intervention participants had a lower odds than control participants (adjusting for baseline levels) of frequent alcohol (OR = 0.16, p=0.10) or frequent marijuana (OR = 0.27, p=0.06) use. They also had a decreased odds of reporting that their close friends were gang affiliated (OR = 0.40, p=0.10).

Table 3.

Evidence for effects of Yo Puedo at six-months on behaviors associated with sexual health outcomes Yo Puedo Feasibility Study, 2011–2012

| Intent to Treata N=162 |

Per-Protocolb | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR | p-value | ORc | p-value | |

| Friend Risk Profile | ||||

| Close friends gang affiliated | 0.71 | 0.31 | 0.40* | 0.10 |

| Close friends detained | 0.60 | 0.12 | 0.37* | 0.09 |

| Individual Behavior | ||||

| Hangs out on the corner frequently | 0.54* | 0.10 | 0.46 | 0.15 |

| Frequent alcohol use in past 6 months | 0.76 | 0.50 | 0.16* | 0.10 |

| Frequently used marijuana in the past 6 months | 0.59 | 0.13 | 0.10** | 0.02 |

| Any sex in the past 6 months | 0.50** | 0.04 | 0.57 | 0.35 |

| Unprotected sex at last sex | 0.42 | 0.12 | 0.24 | 0.21 |

| Contraceptive efficacy and motivation (continuous) (β) | −0.13* | 0.07 | −0.03 | 0.75 |

| Reproductive Health Service Use | ||||

| Accessed reproductive health services in the past 6 months | 1.24 | 0.52 | 1.92 | 0.21 |

| Enrolled in Family PACT | 0.69 | 0.31 | 1.74 | 0.53 |

| STI test in past 6 months | 0.80 | 0.58 | 1.43 | 0.61 |

p≤0.1;

p≤0.05.

ITT: Intervention N=79; Control N=83.

Per-Protocol: Adherent (attended 3+ sessions and received at least one CCT payment) N=31; Control N=83.

Effect estimates adjusted for baseline level of the outcome examined and, in all models, baseline covariates that differed significantly between adherent and control participants, including: high-risk close (gang involved or detained within past 6 months); frequent substance use (marijuana and/or alcohol at least weekly); and attended middle school in the U.S.

Discussion

The Yo Puedo intervention builds on our multi-phase research program in San Francisco’s Mission District that has examined social environment influences on adolescent reproductive health. Our past research provided evidence of high levels of teen pregnancy, over three-quarters of it unintended; evidence that having a male partner who belonged to a gang increased pregnancy incidence; and evidence, in a qualitative study, that gang exposure through families and neighborhood increased detachment from stated future educational and career goals, making early childbearing more common. Furthermore, social network characteristics influenced pregnancy, with a higher risk friend group associated with increased pregnancy incidence; a higher score on a scale of closeness to friends was associated with decreased pregnancy incidence. Thus, we designed Yo Puedo to address dominant social network influences in this community (e.g., gang affiliation, cultural and neighborhood norms tied to childbearing), to target small social networks, to encourage performance goals, and to create positive social support through the life skills groups.

Given the short intervention period, findings related to changes in individual behavior and social network composition suggest Yo Puedo shows promise and warrants further evaluation for its effects on sexual health outcomes. The findings that youth randomized to the intervention and those who were considered adherent spent less time hanging out on the street and had a non-significant but consistently lower odds of reporting incarcerated and gang-affiliated friends at follow-up suggests shifts in the composition of their network of close friends. It is conceivable that, as described by social contagion theory whereby even indirect social links influence behavior (38), these differences between intervention and control participants reflect changes in social network norms and behaviors. Though we did not explicitly include substance use prevention as part of the life skills curriculum, we did observe decreased alcohol and marijuana use among intervention participants. A vast literature highlights the negative effects of frequent substance use during adolescence on educational attainment (39); thus, it may be that the reduction in frequent alcohol and marijuana use reflects an increased focus on future achievement. Certainly, the Yo Puedo intervention delivered to peer networks from the same social environment over a longer period of time carries potential for improving neighborhood-level health and educational attainment outcomes. Whether these positive behavioral changes would be sustained over time and whether they ultimately lead to improved educational and reproductive health outcomes requires further evaluation.

Based on the conceptual model guiding our intervention we hypothesized that contraceptive self-efficacy and motivation would be positively influenced by Yo Puedoyet we found lower self-efficacy among intervention participants (p=0.07) in the ITT analysis, a finding that did not remain significant in per-protocol analysis. This could be due to participants who received a “low dose” of the intervention having a greater appreciation for the challenges in achieving their stated desire not to become pregnant and negotiating method use in the context of sexual partnerships, yet an insufficiently “high dose” of the intervention to feel confident in their ability to overcome these challenges and believe they could actually use effective methods consistently.

Yo Puedo adherence was lower, overall, than we had anticipated, highlighting challenges in mobilizing high-risk youth. Even in interventions demonstrating effectiveness in promoting sexual health behaviors, such as Prime Time (a youth development intervention), adherence across components varied (40). Our adherence findings prompt several modifications to the intervention design. We would convert the 8-session life skills model to two half-day workshops held in the first month of the intervention. We would incentivize workshop participation and attendance would then grant youth the opportunity to receive compensation for completing CCT-incentivized activities. To leverage positive social influence, we would incentivize goal completion by all social network members (e.g., an individual would receive $10 for a reproductive health wellness visit but $20 if all network members completed the visit). Finally, given the central role that technology-based communication assumes among youth, we would develop a Yo Puedo “app” to facilitate text messaging, information dissemination, and strengthening of social network support for goal completion.

Although CCT interventions have been implemented in numerous settings, Yo Puedo is unique in targeting youth and members of their social networks directly, in distributing all reward payments to youth, in empowering youth to set personalized educational goals, and in integrating a tailored life skills curriculum designed to support goal completion and promote sexual health. This randomized evaluation provided evidence of feasibility, informed several design modifications to increase intervention uptake and adherence, and provided preliminary evidence of effects on intermediate behavioral outcomes associated with adverse reproductive health outcomes.

Implications and Contribution.

Yo Puedo, a combined conditional cash transfer and life skills intervention designed to improve adolescent sexual health, directly targeted youth and their social networks. The randomized evaluation provided evidence of feasibility, informed design modifications, and provided preliminary evidence of effects on intermediate outcomes associated with adverse reproductive health outcomes.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Monica Martinez and Adriana Reyes for their dedicated work as Yo Puedo research assistants and Helen Cheng for her contributions as the study’s data manager. We are grateful to our community partners who contributed to intervention design and supported study implementation, including: the wellness centers at Mission and John O’Connell High Schools; Precita Center and Mission Girls of Mission Neighborhood Centers; Crisis Response Network; and CARECEN. We also thank Claudia Jasin of Jamestown Community Center and Roberto Ariel Vargas of the UCSF Community-Campus Partnerships for Health for providing guidance on the intervention design. This research was funded by the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (NICHD) at the National Institutes of Health (R21 HD066192; PI, Minnis) and supported by an NICHD career development award to A.M. Minnis (K01 HD47434).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Dr. Minnis presented the findings reported in this manuscript in an oral presentation at the STI & AIDS World Congress held in Vienna, Austria in July 2013.

References

- 1.Amaral G, Foster DG, Biggs MA, Jasik CB, Judd S, Brindis CD. Public savings from the prevention of unintended pregnancy: a cost analysis of family planning services in California. Health services research. 2007;42(5):1960–1980. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6773.2007.00702.x. Epub 2007/09/14. doi:10.1111/j.1475-6773.2007.00702.x. PubMed PMID:17850528; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC2254565. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Patel PH, Sen B. Teen motherhood and long-term health consequences. Matern Child Health J. 2012;16(5):1063–1071. doi: 10.1007/s10995-011-0829-2. Epub 2011/06/10. doi:10.1007/s10995-011-0829-2. PubMed PMID: 21656056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Santelli JS, Melnikas AJ. Teen fertility in transition: recent and historic trends in the United States. Annu Rev Public Health. 2010;31:371–383. doi: 10.1146/annurev.publhealth.29.020907.090830. 4 p following 83. Epub 2010/01/15. doi: 10.1146/annurev.publhealth.29.020907.090830. PubMed PMID: 20070205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Vital signs: teen pregnancy - United States, 1991–2009. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2011;60(13):414–420. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.American Community Survey 1-year Estimates, Table B01001 Sex By Age. http://factfinder2.census.gov/faces/nav/jsf/pages/searchresults.xhtml?refresh=t2011.

- 6.California Department of Public Health, California's Teen Births Continue Decline. 2011 Available from: http://www.cdph.ca/gov/Pages/NR11-008.aspx.

- 7.Sexually Transmitted Disease Surveillance 2011. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 2012 [Google Scholar]

- 8.Youth Violence Facts at a Glance. National Center for Injury Prevention and Control, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 2010 [Google Scholar]

- 9.Krohn M, Schmidt N, Lizotte A, Baldwin J. The Impact of Multiple Marginality on Gang Membership and Delinquent Behavior for Hispanic, African American, and White Male Adolescents. J Contemp Crim Justice. 2011;27(1):18–42. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Howell JC. Changing Course: Preventing Gang Membership [Internet] Washington, D.C.: U.S. Department of Justice, Office of Justice Programs and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 2013. Why Is Gang-Membership Prevention Important? pp. 7–18. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rios V. The consequences of the criminal justice pipeline on Black and Latino masculinity. Annals, AAPSS. 2009;623:150–162. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Minnis A, vanDommelen-Gonzalez E. Social influences on relationship fidelity and concurrency patterns among Latino adolescents in San Francisco. International Society for Sexually Transmitted Disease Research Conference Presentation; Quebec City, Quebec. 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Marcus R. Cross-sectional study of violence in emerging adulthood. Aggress Behav. 2009;35(2):188–202. doi: 10.1002/ab.20293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Voisin DR, Jenkins EJ, Takahashi L. Toward a conceptual model linking community violence exposure to HIV-related risk behaviors among adolescents: directions for research. The Journal of adolescent health : official publication of the Society for Adolescent Medicine. 2011;49(3):230–236. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2011.01.002. Epub 2011/08/23. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2011.01.002. PubMed PMID: 21856513; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC3329930. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Reed E, Silverman JG, Welles SL, Santana MC, Missmer SA, Raj A. Associations between perceptions and involvement in neighborhood violence and intimate partner violence perpetration among urban, African American men. J Community Health. 2009;34(4):328–335. doi: 10.1007/s10900-009-9161-9. Epub 2009/04/04. doi: 10.1007/s10900-009-9161-9. PubMed PMID: 19343487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Minnis A, Moore J, Doherty I, Rodas C, Auerswald C, Shiboski S, et al. Gang exposure and pregnancy incidence among female adolescents in San Francisco: evidence for the need to integrate reproductive health with violence prevention efforts. American journal of epidemiology. 2008;167(9):1102–1109. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwn011. Epub 2008/03/01. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwn011. PubMed PMID: 18308693. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Voisin DR, Salazar LF, Crosby R, DiClemente RJ, Yarber WL, Staples-Horne M. The association between gang involvement and sexual behaviours among detained adolescent males. Sexually transmitted infections. 2004;80(6):440–442. doi: 10.1136/sti.2004.010926. Epub 2004/12/02. doi: 80/6/440 [pii] 10.1136/sti.2004.010926. PubMed PMID: 15572610; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC1744945. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wingood GM, DiClemente RJ, Crosby R, Harrington K, Davies SL, Hook EW., 3rd Gang involvement and the health of African American female adolescents. Pediatrics. 2002;110(5):e57. doi: 10.1542/peds.110.5.e57. Epub 2002/11/05. PubMed PMID: 12415063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Penman-Aguilar A, Carter M, Snead MC, Kourtis AP. Socioeconomic disadvantage as a social determinant of teen childbearing in the U.S. Public health reports. 2013;128(Suppl 1):5–22. doi: 10.1177/00333549131282S102. PubMed PMID: 23450881; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC3562742. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Oman R, Vesely S, Aspy C. Youth assets and sexual risk behavior: the importance of assets for youth residing in one-parent households. Perspect Sex Reprod Health. 2005;37(1):25–31. doi: 10.1363/psrh.37.25.05. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Minnis AM, Marchi K, Ralph L, Biggs MA, Combellick S, Arons A, et al. Limited socioeconomic opportunities and latina teen childbearing: a qualitative study of family and structural factors affecting future expectations. Journal of immigrant and minority health / Center for Minority Public Health. 2013;15(2):334–340. doi: 10.1007/s10903-012-9653-z. Epub 2012/06/09. doi: 10.1007/s10903-012- 9653-z. PubMed PMID: 22678305; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC3479330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ranganathan M, Lagarde M. Promoting healthy behaviours and improving health outcomes in low and middle income countries: a review of the impact of conditional cash transfer programmes. Preventive medicine. 2012;55(Suppl):S95–S105. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2011.11.015. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2011.11.015. PubMed PMID: 22178043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pettifor A, MacPhail C, Nguyen N, Rosenberg M. Can money prevent the spread of HIV? A review of cash payments for HIV prevention. AIDS and behavior. 2012;16(7):1729–1738. doi: 10.1007/s10461-012-0240-z. doi: 10.1007/s10461-012-0240-z. PubMed PMID: 22760738; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC3608680. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Baird SJ, Garfein RS, McIntosh CT, Ozler B. Effect of a cash transfer programme for schooling on prevalence of HIV and herpes simplex type 2 in Malawi: a cluster randomised trial. Lancet. 2012;379(9823):1320–1329. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)61709-1. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)61709-1. PubMed PMID: 22341825. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.McDougall J, Greene M, Golla A. Just a Little Bit Later: Examining the Effects of Conditional Cash Transfers on Age at Marriage Among Poor Girls in Mexico. Annual Meeting of the Population Association of America; April 30–May 2; Detroit, MI. 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Morris P, Aber J, Wolf S, Berg J. Using incentives to change how teenagers spend their time: the effects of New York City's conditional cash transfer program. 2012 Available from: http://www.mdrc.org/publications/647/full.pdf.

- 27.Sridhar D, Duffield A. A review of the impact of cash transfer programmes on child nutritional status and some implications for Save the Children UK programmes. Save the Children. 2006 [Google Scholar]

- 28.Silverman K, Roll JM, Higgins ST. Introduction to the special issue on the behavior analysis and treatment of drug addiction. Journal of applied behavior analysis. 2008;41(4):471–80. doi: 10.1901/jaba.2008.41-471. PubMed PMID: 19192853; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC2606609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.O'Donoghue T, Rabin M. In: Risky Behavior Among Youths: Some Issues from Behavioral Economics. Gruber J, editor. Youthful Risky Behavior: An Economic Perspective: University of Chicago Press and NBER; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bandura A. Social Learning Theory. New York: General Learning Press; 1977. [Google Scholar]

- 31.What Works 2008: Curriculm-Based Programs that Prevent Teen Pregnancy: National Campaign to Prevent Teen and Unintended Pregnancy. [cited 2009 September 9]. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Social Cognitive Strategy: Curriculum Scope for Different Age Groups. Best Practices for Youth Violence Prevention: A Sourcebook for Community Action. Atlanta, GA: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 2002. pp. 153–160. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Loewenstein G, Asch DA, Friedman JY, Melichar LA, Volpp KG. Can behavioural economics make us healthier? BMJ. 2012;344:e3482. doi: 10.1136/bmj.e3482. Epub 2012/05/25. doi: 10.1136/bmj.e3482. PubMed PMID: 22623635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Homonoff TA. Can small incentives have large effects? The impact of taxes versus bonuses on disposable bag use. 2013 Mar 27; Available from: http://www.princeton.edu/~homonoff/THomonoff_JobMarketPaper.

- 35.Galarraga O, Sosa-Rubi SG, Infante C, Gertler PJ, Bertozzi SM. Willingness-to-accept reductions in HIV risks: conditional economic incentives in Mexico. The European journal of health economics: HEPAC: health economics in prevention and care. 2013 doi: 10.1007/s10198-012-0447-y. doi: 10.1007/s10198-012-0447-y. PubMed PMID: 23377757. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Skills for Youth. 2009 Available from: http://www.etr.org/recapp/index.cfm?fuseaction=pages.youthskillshome.

- 37.Auerswald CL, Greene K, Minnis A, Doherty I, Ellen J, Padian N. Qualitative assessment of venues for purposive sampling of hard-to-reach youth: an illustration in a Latino community. Sexually transmitted diseases. 2004;31(2):133–138. doi: 10.1097/01.OLQ.0000109513.30732.B6. Epub 2004/01/27. doi: 10.1097/01.OLQ.0000109513.30732.B6. PubMed PMID: 14743078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Christakis NA, Fowler JH. Social contagion theory: examining dynamic social networks and human behavior. Statistics in medicine. 2013;32(4):556–577. doi: 10.1002/sim.5408. doi: 10.1002/sim.5408. PubMed PMID: 22711416. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lynskey M, Hall W. The effects of adolescent cannabis use on educational attainment: a review. Addiction. 2000;95(11):1621–1630. doi: 10.1046/j.1360-0443.2000.951116213.x. PubMed PMID: 11219366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sieving RE, McRee AL, McMorris BJ, Beckman KJ, Pettingell SL, Bearinger LH, et al. Prime time: sexual health outcomes at 24 months for a clinic-linked intervention to prevent pregnancy risk behaviors. JAMA pediatrics. 2013;167(4):333–340. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2013.1089. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2013.1089. PubMed PMID: 23440337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]