Abstract

Purpose

To compare the use of antihypertensive medications and diagnostic tests among adolescents and young adults with primary vs. secondary hypertension

Methods

We conducted retrospective cohort analysis of claims data for adolescents and young adults (12–21 years) with ≥ 3 years of insurance coverage (≥ 11 months/year) in a large private managed care plan during 2003–2009 with diagnosis of primary hypertension or secondary hypertension. We examined their use of antihypertensive medications and identified demographic characteristics and presence of obesity-related comorbidities. For the subset receiving antihypertensive medications, we examined their diagnostic test use (echocardiograms, renal ultrasounds, and electrocardiograms (EKG)).

Results

Study sample included 1232 adolescents and young adults; 84% had primary hypertension and 16% had secondary hypertension. Overall prevalence rate of hypertension was 2.6%. One-quarter (28%) with primary hypertension had ≥1 antihypertensive medication whereas 65% with secondary hypertension had ≥1 antihypertensive medication. Leading prescribers of antihypertensives for subjects with primary hypertension were primary care physicians (PCP) (80%) whereas antihypertensive medications were equally prescribed by PCPs (43%) and subspecialists (37%) for subjects with secondary hypertension.

Conclusions

The predominant hypertension diagnosis among adolescents and young adults is primary hypertension. Antihypertensive medication use was higher among those with secondary hypertension compared to those with primary hypertension. Further study is needed to determine treatment effectiveness and patient outcomes associated with differential treatment patterns used for adolescents and young adults with primary vs. secondary hypertension.

Keywords: primary hypertension, secondary hypertension, adolescents, blood pressure medication, diagnostic test use

INTRODUCTION

Hypertension in adolescents and young adults may be secondary to renal, cardiac, or other etiologies or have no known cause (primary hypertension). Primary hypertension among adolescents and young adults is a growing concern due to high rates of obesity among US youth.1–3 Previous studies have shown that about one-half of pediatric hypertension patients ≤18 years of age had primary hypertension4–9, with 17% of young children (< 6 years old) compared to 60% or more of 6–11 year olds and adolescents 12–16 years old having primary hypertension.5 Although these were relatively smaller studies conducted mostly at single referral centers and one multicenter study, these studies suggest an important epidemiologic shift in pediatric hypertension from largely secondary to primary hypertension with increasing patient age. Despite this changing epidemiology, the diagnosis, workup and treatment of hypertension in children and adolescents still remain largely in the pediatric subspecialty domain whereas the treatment of hypertension in adults largely occurs in the primary care setting.

Hypertension management for adolescents and young adults may vary depending on the specialty of their providers (pediatric vs. adult; primary care vs. subspecialty) particularly given the differences in pediatric vs. adult hypertension guidelines. Previous studies have described unexpected antihypertensive prescribing patterns for adolescents with primary hypertension with Medicaid coverage where primary care physicians who provided care for both adults and children – primarily family practitioners were leading prescribers of antihypertensive medications.10 Moreover, previous studies have also demonstrated common use of adult hypertension guideline-recommended diagnostic tests11 – electrocardiograms (EKG) – for adolescents with primary hypertension with Medicaid coverage whereas pediatric hypertension guideline-recommended12 diagnostic tests (echocardiograms and renal ultrasounds) were uncommonly used. 13 Prior work in adults suggest that physician prescribing patterns are influenced by limited availability and/or cost of medications (higher tiers) offered by insurance plan formularies.14–17 Given that insurance coverage could affect both the use of medications and diagnostic tests for adolescents and young adults with hypertension, we set out to characterize the use of antihypertensive medications and diagnostic tests among privately-insured adolescents with primary hypertension vs. secondary hypertension.

METHODS

Study Design

We conducted a retrospective cohort analysis of claims and pharmacy data from a large private managed care plan in Michigan for adolescents and young adults 12–21 years old during 2003–2009. The private managed care plan in Michigan is a nonprofit organization serving nearly 700,000 members across various geographic regions of Michigan including southeastern, mid and Upper Peninsula. Its network includes more than 5,000 primary care physicians, over 15,000 specialists and most of the state’s leading hospitals. We identified subjects with primary hypertension and secondary hypertension and examined their use of antihypertensive medications. For the subset who received antihypertensive medications, we examined their use of diagnostic tests (echocardiograms, renal ultrasounds, and EKGs). This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of University of Michigan Medical School.

Study Population

Our study population was defined as those who were aged 12–18 years on 12/31/2003 who had medical and prescription coverage for at least 3 of 7 years (≥11 months per year) at any time during 1/1/2003–12/31/2009. We excluded years where they had other insurance coverage or had age >21 years. If subjects had ≥1 visit with ICD-9-CM code for secondary hypertension (402.x, 403.x, 404.x, 405.x) or common pediatric cause of secondary hypertension such as renal disease at any time during the study period, we considered them to have secondary hypertension. We considered subjects to have primary hypertension if they had ≥1 visit with ICD-9 -CM code for hypertension (401.x) and no secondary hypertension. A full list of inclusion and exclusion codes is found in Appendix 1.

Variables of Interest

Antihypertensive pharmacotherapy

Using pharmacy claims and National Drug Codes, we identified adolescents and young adults who had ≥1 claim for the following antihypertensive drug classes: angiotensin converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors (including angiotensin receptor blockers (ARB)), β-blockers, calcium channel blockers, diuretics and centrally acting agents (including clonidine and guanfacine).12 Prescriber identification numbers on pharmacy claims were linked to physician specialty data. From this analytic file, we created the following variables:

Receipt of ≥1 antihypertensive medication during the study period.

Class of antihypertensive medication.

Monotherapy vs. combination therapy: Monotherapy was defined as having prescription claims for only one antihypertensive medication per day. Subjects with multiple antihypertensive single drugs were categorized as the drug class of the last antihypertensive prescription claim, to allow mutually exclusive groups. Combination therapy was defined as prescription claims for 2 different drug classes on the same or ± 1 day or ≥1 claim for a combination medication (i.e., one medication formulated with two antihypertensive drugs, such as Lotensin HCT™). Subjects who received combination therapy at any time during the study period were classified as having combination therapy, even if they had periods of monotherapy.

Median number of hypertension visits per year of eligibility

Years of insurance coverage (3–4 years vs. 5–7 years)

Specialty of physician who first prescribed the antihypertensive drug class determined for the study period was categorized as primary care physicians (PCP)(family physicians, general practitioners, internists, medicine-pediatrics, and general pediatricians), subspecialists, and unknown specialty.

Diagnostic Tests

We considered subjects to have had an echocardiogram if they had ≥ 1 claim with current procedural terminology (CPT) codes 93303, 93304, 93307, 93308, 93320, 93321, 93325, 93350 or ICD-9-CM procedure codes 88.72, 37.28 or revenue code 0483.

We considered subjects to have had a renal ultrasound if they had ≥ 1 claim with CPT codes 76770, 76775, or ICD-9-CM procedure code 88.76.

We considered subjects to have had an EKG if they had ≥ 1 with CPT codes 93000, 93005, 93010, 93040, 93041, 93042 or ICD-9-CM procedure codes 89.51, 89.52. Although EKGs are not recommended in the evaluation of pediatric hypertension, we included EKGs in our analyses because young adults are in our study sample and EKGs are recommended routinely in the evaluation of adults with hypertension.18

Independent Variables

Demographic variables included age at first hypertension diagnosis during the study period categorized as: younger adolescents (12–14 years), older adolescents (15–17 years), and young adults (18–21 years); race categorized as Caucasian, African-American, and other/unknown; and gender. We also included years of insurance coverage. Presence of obesity-related comorbidities defined as having ≥1 visit with an ICD-9-CM code for obesity (278.00, 278.01, 278.02, V85.3, V85.4, V85.54), hyperlipidemia (272.0, 272.1, 272.2, 272.3, and 272.4), diabetes mellitus type 2 (250.x0, 250.x2), metabolic syndrome (277.7), or obstructive sleep apnea (327.23).

Statistical Analysis

Descriptive analyses included simple counts and proportions. We used χ2 tests and multivariate logistic regression to evaluate the associations between demographic characteristics, obesity-comorbidity status and receipt of antihypertensive medications for subjects with primary versus secondary hypertension.

For the subset who received antihypertensive medications, we used χ2 tests to evaluate the associations between demographic characteristics, renal ultrasound use, EKG use and echocardiogram use. P values < 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

Of the 47,405 subjects 12–18 years of age as of 12/31/2003 with at least 3 years of insurance coverage (≥11 months), 2,220 had at least one primary hypertension or secondary hypertension diagnosis. We excluded 27 subjects who had other insurance coverage leaving 2,193 subjects. From this, we identified 1,345 subjects with a diagnosis of primary or secondary hypertension at an outpatient visit. Then we excluded those with malignant, ocular, portal, pulmonary or pregnancy-related hypertension resulting in our final study sample of 1,232. Thus, the overall prevalence of hypertension (primary and secondary) in our study sample was 2.6% (2.2% primary hypertension + 0.4% secondary hypertension).

Study sample characteristics

Of the 1,232 subjects in the study sample, 84% had primary hypertension and 16% had secondary hypertension. The leading causes of secondary hypertension was renal disorders (66%), congenital anomalies (e.g., coarctation of aorta) (5%), and 29% with no other diagnoses other than secondary hypertension. Overall, most (65%) were male; 53% were ages 18–21 years at first hypertension diagnosis; 72% were Caucasian, 14% African American, 14% other/unknown (Table 1). One-third (34%) had an obesity-related comorbidity. Our sample demographics (N=1232) were similar to the overall population of the private managed care plan with the exception of gender where one-third of our sample were girls whereas gender was more evenly distributed in the overall managed care population. Study sample demographic characteristics by hypertension diagnosis are described in Table 1. Notably, more males had primary hypertension whereas more females had secondary hypertension. Those with primary hypertension were older at first hypertension diagnosis during the study period. Median number of hypertension visits per year of eligibility was less for those with primary hypertension (Median 0.3; Range 0.1–3.7 visits) compared to secondary hypertension (Median 0.6; Range 0.1–8.4 visits; p<.0001).

Table 1.

Demographic characteristics of privately-insured adolescents and young adults by hypertension diagnosis (N=1232).

| Primary HTN N=1039 |

Secondary HTN N=193 |

Overall N=1232 |

|

|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||

| Gender | |||

| Male* | 69% | 44% | 65% |

| Female | 31% | 56% | 35% |

|

| |||

| Age at first HTN diagnosis (y) | |||

| 12–14* | 7% | 12% | 8% |

| 15–17 | 39% | 42% | 39% |

| 18–21 | 54% | 46% | 53% |

|

| |||

| Race | |||

| Caucasian | 72% | 74% | 72% |

| African American | 14% | 14% | 14% |

| Other/Unknown | 14% | 12% | 14% |

|

| |||

| Years of insurance coverage | |||

| 3–4 | 42% | 45% | 43% |

| 5–7 | 58% | 55% | 57% |

|

| |||

| Obesity-related comorbidity | |||

| Yes | 35% | 30% | 34% |

| No | 65% | 70% | 66% |

denotes statistical significance of p<.05

Characteristics associated with receipt of antihypertensive medications

One-quarter (28% N=294) of adolescents and young adults with primary hypertension had ≥1 antihypertensive medication during the study period whereas 65% (N=126) of adolescents and young adults with secondary hypertension received antihypertensive medication. Older age was associated with receipt of antihypertensive medication for those with primary hypertension whereas females were more likely to receive antihypertensive medication than males among those with secondary hypertension (Table 2). African-American and Caucasian subjects with primary hypertension were more likely to receive antihypertensive medication than those of other/unknown race (Table 2). Obesity-related comorbidity was associated with receipt of antihypertensive medication for adolescents and young adults with primary hypertension (Table 2).

Table 2.

Characteristics associated with receipt of antihypertensive medication by hypertension diagnosis.

| % adolescents and young adults with primary hypertension with medication (N=1039) | % adolescents and young adults with secondary hypertension with medication (N=193) | |

|---|---|---|

|

| ||

| Overall | 28%* | 65% |

|

| ||

| Gender | ||

| Male | 28% | 58%* |

| Female | 29% | 71% |

|

| ||

| Age at first HTN diagnosis (y) | ||

| 12–14 | 12%* | 48% |

| 15–17 | 24% | 69% |

| 18–21 | 34% | 66% |

|

| ||

| Race | ||

| Caucasian | 30%* | 67% |

| African American | 32% | 62% |

| Other/Unknown | 18% | 58% |

|

| ||

| Years of insurance coverage | ||

| 3–4 | 29% | 70% |

| 5–7 | 28% | 61% |

|

| ||

| Obesity-related comorbidity | ||

| Yes | 37%* | 71% |

| No | 23% | 63% |

denotes statistical significance of p<.05

Antihypertensive prescribing patterns for adolescents and young adults with primary hypertension (N=294) vs. secondary hypertension (N=126)

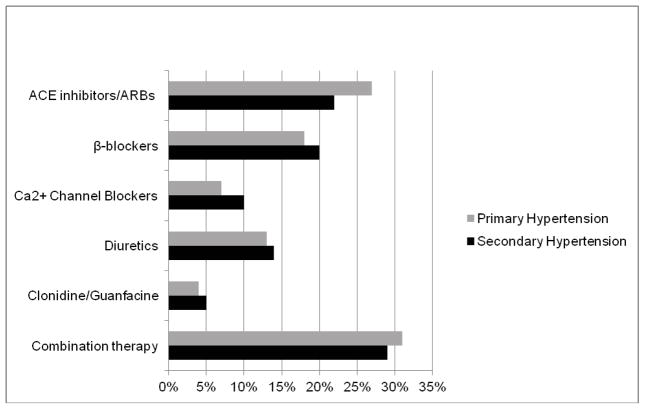

Of 294 adolescents and young adults with primary hypertension who received antihypertensive medications, 69% (N=204) received monotherapy; ACE inhibitors/ARBs were the most commonly prescribed monotherapy (Figure 1). Nearly one-third of adolescents received combination therapy Figure 1. The 3 most commonly prescribed drug combinations for adolescents with primary hypertension were ACE-DIU, DIU-DIU, and BB-DIU combinations. Most antihypertensive medications (80%) were prescribed by primary care physicians (PCPs) – mainly family practitioners; 11% from subspecialists and 9% from physicians of unknown specialty.

Figure 1. Antihypertensive medications for adolescents and young adults with primary vs. secondary hypertension (N=420).

Statistically significant at p<.05

Of 126 adolescents and young adults with secondary hypertension who received antihypertensive medications, 71% (N=89) received monotherapy; ACE inhibitors/ARBs and β-blockers were the more commonly prescribed monotherapy (Figure 1). The 3 most commonly prescribed drug combinations for adolescents with secondary hypertension were ACE-DIU, DIU-DIU, and ACE-CCB combinations. Antihypertensive medications were nearly equally prescribed by PCPs (N= 54; 43%) and subspecialists (N=46; 37%); 21% prescribed by physicians of unknown specialty.

Frequency of diagnostic test use among those with antihypertensive medications

Echocardiogram use during the study period was similar among those with primary (27%) vs. secondary hypertension (29%). EKG use during the study period was also similar between those with primary (50%) vs. secondary hypertension (48%). While 46% of subjects with secondary hypertension had a renal ultrasound, only 12% of subjects with primary hypertension had a renal ultrasound (p<.0001).

Notably, two out of five adolescents and young adults with primary hypertension (40%) did not have any diagnostic tests evaluated in our study (EKG, echocardiogram and renal ultrasound) during the study period (Table 3). One-third of subjects with either primary or secondary hypertension had only 1 diagnostic test – largely an EKG for those with primary hypertension and renal ultrasound for those with secondary hypertension (Table 3). Only 5% of those with primary hypertension and 14% of those with secondary hypertension had both pediatric hypertension guideline-recommended tests - echocardiogram and renal ultrasound (Table 3).

Table 3.

Echocardiogram, renal ultrasound and EKG use among adolescents and young adults with primary vs. secondary hypertension with antihypertensive medication

| Diagnostic Tests | Primary hypertension | Secondary Hypertension | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| No Tests | 119 | 40% | 33 | 26% |

| One Test | ||||

| Echo Only | 15 | 5% | 1 | 1% |

| Renal Ultrasound Only | 9 | 3% | 26 | 21% |

| EKG Only | 75 | 26% | 17 | 13.5% |

| Two Tests | ||||

| EKG and Echo | 50 | 17% | 17 | 13.5% |

| EKG and Renal Ultrasound | 11 | 4% | 14 | 11% |

| Echo and Renal Ultrasound | 3 | 1% | 5 | 4% |

| Three Tests | ||||

| Echo, Renal Ultrasound and EKG | 12 | 4% | 13 | 10% |

| Total | 294 | 126 | ||

Echo = echocardiogram; EKG = electrocardiogram

Characteristics associated with diagnostic test use

Among subjects with primary hypertension, those 12–14 years of age at the time of diagnosis were more likely (67%) to get an echocardiogram than those who were older (34% for 15–17 years and 22% for 18–21 years; p=.0020). Also, among those with primary hypertension, subjects with longer duration of insurance coverage (5–7 years; 32%) were more likely than those with 3–4 years of coverage (21%) to get an echocardiogram (p=.0385). Among subjects with secondary hypertension, males (39%) were more likely to get an echocardiogram than females (22%; p=.0431). There were no race differences noted in the use of diagnostic tests among those with primary or secondary hypertension.

Multivariate Logistic Regression Analysis

Among adolescents and young adults with hypertension diagnosis (primary or secondary), receipt of antihypertensive medications was significantly associated with secondary hypertension, older age at first hypertension diagnosis, and obesity comorbidity status in our multivariate logistic regression model (Table 4). Controlling for gender, race, and years of insurance coverage, those with secondary hypertension, young adults (18–21 years) and older adolescents (15–17 years), and those with obesity comorbidity were more likely to receive an antihypertensive medication compared to those with primary hypertension, younger adolescents (12–14 years), and those without comorbidity. Subjects with other or unknown race were less likely to receive antihypertensive medications compared to the reference group African-Americans.

Table 4.

Multivariate logistic regression of characteristics associated with receipt of antihypertensive medication among adolescents and young adults with primary vs. secondary hypertension (N=1232)

| Odds Ratio | 95% Confidence Interval | |

|---|---|---|

|

| ||

| Secondary hypertension (Ref = primary hypertension) | 5.61 | 3.95–7.95 |

|

| ||

| Female (Ref=Male) | 1.06 | 0.81–1.39 |

|

| ||

| Age at first hypertension diagnosis | ||

| 15–17y (Ref=12–14y) | 2.27 | 1.28–4.00 |

| 18–21y | 3.28 | 1.87–5.76 |

|

| ||

| Race | ||

| Caucasian (Ref=African-American) | 0.94 | 0.66–1.35 |

| Other/Unknown | 0.53 | 0.32–0.87 |

|

| ||

| Has obesity comorbidity (Ref= No comorbidity) | 1.90 | 1.46–2.47 |

|

| ||

| 5–7 years of insurance coverage (Ref=3–4years) | 0.94 | 0.73–1.21 |

DISCUSSION

The overall prevalence of hypertension in adolescents and young adults in our claims-based study (2.6%) is consistent with previous prevalence estimates of 2–5% based on clinical blood pressure measurements.2,3 Moreover, the predominant hypertension diagnosis among adolescents and young adults is primary hypertension. Prior work has shown general pediatrician’s discomfort in evaluation and treatment of adolescents with hypertension citing inadequate training and knowledge of antihypertensive medications.19 Given the increasing trend and market share of adolescent patients receiving primary care services from general pediatricians compared to family practitioners,20 medical education programs should consider focusing on providing appropriate training in the diagnosis and management of adolescents and young adults with primary hypertension for general pediatricians in training and those already in practice.

We also demonstrate that the diagnosis of hypertension whether primary or secondary among adolescents and young adults is made most commonly when they are young adults 18–21years of age (46–54%) and older adolescents 15–17 years (39–42%). Given that young adults 18–21 years of age may transfer their medical care from pediatric to adult primary care physicians (PCPs) during this time period, the diagnosing provider could have been an adult PCP. Thus, it is understandable why adult PCPs played a central role in prescribing antihypertensive medications to adolescents and young adults with primary and secondary hypertension in our study. It also makes sense why EKGs – an adult hypertension guideline-recommended test 11 – was the most frequently used diagnostic test (alone or in combination with other diagnostic tests) for subjects with primary and secondary hypertension in our study. However, whether the patterns of diagnostic test utilization confirmed in this study reflect application of adult or pediatric hypertension guidelines versus convenience of obtaining diagnostic tests is unclear. Physicians may also be unclear about which hypertension guidelines – pediatric or adult – should be applied for the older adolescent and young adult patients under their care and by default follow the guideline they are more familiar with depending on their specialty training. Thus, it is crucial to understand the underlying physician clinical decision-making process in the management of hypertension in adolescents and young adults among primary care physicians who provide their medical care.

At the same time, older adolescence and young adulthood is also a personal transition period of increased autonomy and responsibility with variable level of maturity and capability to helm their own medical care and navigate the health care system. Hypertension is often asymptomatic rendering it that much more difficult to emphasize to adolescents and young adults the importance of adherence to pharmacotherapy, diagnostic tests, and/or blood pressure monitoring and follow up now in order to prevent potentially devastating downstream effects of uncontrolled hypertension. Other chronic disease populations in this age group have demonstrated underutilization of medical care and loss to follow up;21–23 thus, every effort should be made to effectively communicate the recommended plan of care and encourage responsibility for one’s own health and medical care for the older adolescent and young adult patients.

Our study confirms similar use of pediatric hypertension guideline-recommended diagnostic tests – echocardiograms (27%) and renal ultrasounds (12%) – among privately-insured adolescents and young adults with primary hypertension as previously published for Medicaid-insured counterparts.13 It is important to note that the main use of renal ultrasounds is to rule out potential renal causes of secondary hypertension whereas echocardiograms and EKGs are used to evaluate left ventricular hypertrophy and end organ abnormalities. Although, nearly one-half of adolescents and young adults with secondary hypertension had a renal ultrasound, the overall use of pediatric guideline-recommended diagnostic tests – echocardiograms and renal ultrasounds – was poor regardless of hypertension type.

Lastly, it is not surprising that the most common cause of secondary hypertension was renal disorders. Furthermore, it is not surprising that antihypertensive medication use was notably higher among those with secondary hypertension compared to those with primary hypertension.24 The patterns of use of antihypertensive medications among adolescents and young adults with primary hypertension in this study’s privately-insured population was similar to previously published findings in Medicaid-insured counterparts.10 Moreover, adolescents and young adults with primary hypertension with obesity-related comorbidity had higher likelihood of receiving antihypertensive medications in this study as seen previously in Medicaid-insured counterparts.10 This is consistent with pediatric hypertension guidelines that recommend treatment with antihypertensive pharmacotherapy for patients with obesity-related comorbidities such as diabetes mellitus.12

LIMITATIONS

Our findings should be interpreted with these limitations. First, actual blood pressure measurements of our study sample are unknown given that the study design employed claims analysis and not medical record review. It is possible that the lack of BP information could be associated with potential misclassification of hypertension diagnoses for patients. Second, specialties of physicians ordering diagnostic tests are unknown due to lack of identifiable physician information on procedure claims such as DEA numbers used for pharmacy claims. Thus, it is unknown how diagnostic test ordering might differ among and between various specialties of primary care physicians and subspecialty physicians. Third, timing of diagnostic tests could be subjective to appointment availability, patient schedule and/or patient compliance with obtaining physician-ordered tests. Fourth, we did not examine laboratory test use that may be needed to rule out secondary causes of hypertension in this study. It is possible that the lack of lab test data may underestimate the number of patients who had appropriate hypertension work-up. Fifth, the use of ICD-9 codes to identify patients with hypertension has the potential for misclassification, if the diagnosis of hypertension is not coded consistently. Finally, we acknowledge left censoring issue where we cannot evaluate antihypertensive prescriptions and diagnostic tests used before 2003.

CONCLUSION

The predominant hypertension diagnosis among adolescents and young adults is primary hypertension. Antihypertensive prescription use was notably higher among those with secondary hypertension compared to those with primary hypertension. EKG use was common for adolescents and young adults with primary or secondary hypertension. Further study is needed to determine treatment effectiveness and patient outcomes associated with differential treatment patterns used for adolescents and young adults with primary vs. secondary hypertension.

Supplementary Material

Implications and Contribution.

Primary hypertension is the predominant hypertension diagnoses in adolescents and young adults. However, only one-quarter of subjects with primary hypertension received antihypertensive pharmacotherapy compared to 65% with secondary hypertension. How these differential treatment patterns affect patient outcomes such as level of blood pressure control warrant further study.

Acknowledgments

This study was funded by the National Heart Lung Blood Institute (EYY K23 HL 092060).

ABBREVIATIONS

- ACE

Angiotensin Converting Enzyme

- ARB

Angiotensin Receptor Blockers

- BP

Blood Pressure

- CPT

Current Procedural Terminology

- ECHO

Echocardiogram

- EKG

Electrocardiogram

- ICD-9-CM

International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision, Clinical Modification

- LVH

Left Ventricular Hypertrophy

- PCP

Primary Care Physician

Footnotes

We disclose that there is no affiliation, financial agreement, or other involvement of any author with any company whose product figures prominently in the submitted manuscript so that the editors can discuss with the affected authors whether to print this information and in what manner. All authors have no conflict of interest, real or perceived.

The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Heart, Lung, And Blood Institute or the National Institutes of Health.

Dr. Yoon had full access to all the data in the study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis.

Preliminary data from this study was presented in a poster presentation at the Pediatric Academic Societies Meeting in Washington DC in May 2013.

All authors are responsible for the reported research. We have participated in the concept and design, analysis and interpretation of data, and drafting or revising of the manuscript; and we have approved the manuscript as submitted. Dr. Esther Yoon wrote the first draft of the manuscript and no honorarium, grant, or other form of payment was given to anyone to produce the manuscript. There was no involvement of study sponsors/funding source in 1) study design; 2) the collection, analysis, and interpretation of data; 3) the writing of the report; and 4) the decision to submit the paper for publication.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.McNiece KL, Poffenbarger TS, Turner JL, Franco KD, Sorof JM, Portman RJ. Prevalence of hypertension and pre-hypertension among adolescents. J Pediatr. 2007 Jun;150(6):640–644. 644, e641. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2007.01.052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Muntner P, He J, Cutler JA, Wildman RP, Whelton PK. Trends in blood pressure among children and adolescents. JAMA. 2004 May 5;291(17):2107–2113. doi: 10.1001/jama.291.17.2107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sorof J, Daniels S. Obesity Hypertension in Children: A Problem of Epidemic Proportions. Hypertension. 2002 Oct 1;40(4):441–447. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.0000032940.33466.12. 2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Baracco R, Kapur G, Mattoo T, et al. Prediction of primary vs secondary hypertension in children. J Clin Hypertens (Greenwich) 2012 May;14(5):316–321. doi: 10.1111/j.1751-7176.2012.00603.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Flynn J, Zhang Y, Solar-Yohay S, Shi V. Clinical and demographic characteristics of children with hypertension. Hypertension. 2012 Oct;60(4):1047–1054. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.112.197525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Flynn JT. Hypertension in the young: epidemiology, sequelae and therapy. Nephrology Dialysis Transplantation. 2009 Feb 1;24(2):370–375. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfn597. 2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Flynn JT, Alderman MH. Characteristics of children with primary hypertension seen at a referral center. Pediatr Nephrol. 2005 Jul;20(7):961–966. doi: 10.1007/s00467-005-1855-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wyszynska T, Cichocka E, Wieteska-Klimczak A, Jobs K, Januszewicz P. A single pediatric center experience with 1025 children with hypertension. Acta Paediatr. 1992 Mar;81(3):244–246. doi: 10.1111/j.1651-2227.1992.tb12213.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Croix B, Feig DI. Childhood hypertension is not a silent disease. Pediatr Nephrol. 2006 Apr;21(4):527–532. doi: 10.1007/s00467-006-0013-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yoon EY, Cohn L, Rocchini A, et al. Antihypertensive prescribing patterns for adolescents with primary hypertension. Pediatrics. 2012 Jan;129(1):e1–8. doi: 10.1542/peds.2011-0877. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chobanian AV, Bakris GL, Black HR, et al. Seventh report of the Joint National Committee on Prevention, Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Pressure. Hypertension. 2003 Dec;42(6):1206–1252. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.0000107251.49515.c2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.The fourth report on the diagnosis, evaluation, and treatment of high blood pressure in children and adolescents. Pediatrics. 2004 Aug;114(2 Suppl 4th Report):555–576. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yoon EY, Cohn L, Rocchini A, et al. Use of diagnostic tests in adolescents with essential hypertension. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2012 Sep;166(9):857–862. doi: 10.1001/archpediatrics.2012.1173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Shrank WH, Hoang T, Ettner SL, et al. The implications of choice: prescribing generic or preferred pharmaceuticals improves medication adherence for chronic conditions. Arch Intern Med. 2006 Feb 13;166(3):332–337. doi: 10.1001/archinte.166.3.332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Goldman DP, Joyce GF, Zheng Y. Prescription drug cost sharing: associations with medication and medical utilization and spending and health. JAMA. 2007 Jul 4;298(1):61–69. doi: 10.1001/jama.298.1.61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Joyce GF, Escarce JJ, Solomon MD, Goldman DP. Employer drug benefit plans and spending on prescription drugs. JAMA. 2002 Oct 9;288(14):1733–1739. doi: 10.1001/jama.288.14.1733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kamal-Bahl S, Briesacher B. How do incentive-based formularies influence drug selection and spending for hypertension? Health Aff (Millwood) 2004 Jan-Feb;23(1):227–236. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.23.1.227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chobanian AV, Bakris GL, Black HR, et al. The Seventh Report of the Joint National Committee on Prevention, Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Pressure: the JNC 7 report. JAMA. 2003 May 21;289(19):2560–2572. doi: 10.1001/jama.289.19.2560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Boneparth A, Flynn JT. Evaluation and treatment of hypertension in general pediatric practice. Clin Pediatr (Phila) 2009 Jan;48(1):44–49. doi: 10.1177/0009922808321677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Freed GL, Nahra TA, Wheeler JR. Which physicians are providing health care to America’s children? Trends and changes during the past 20 years. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2004 Jan;158(1):22–26. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.158.1.22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.McManus MA, Pollack LR, Cooley WC, et al. Current Status of Transition Preparation Among Youth With Special Needs in the United States. Pediatrics. 2013 May 13; doi: 10.1542/peds.2012-3050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lotstein DS, Seid M, Klingensmith G, et al. Transition from pediatric to adult care for youth diagnosed with type 1 diabetes in adolescence. Pediatrics. 2013 Apr;131(4):e1062–1070. doi: 10.1542/peds.2012-1450. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.DeBaun MR, Telfair J. Transition and sickle cell disease. Pediatrics. 2012 Nov;130(5):926–935. doi: 10.1542/peds.2011-3049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Welch WP, Yang W, Taylor-Zapata P, Flynn JT. Antihypertensive drug use by children: are the drugs labeled and indicated? J Clin Hypertens (Greenwich) 2012 Jun;14(6):388–395. doi: 10.1111/j.1751-7176.2012.00656.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.