Abstract

Reactions to aspirin and non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs in patients with aspirin-exacerbated respiratory disease (AERD) are triggered when constraints upon activated eosinophils, normally supplied by PGE2, are removed secondary to cyclooxygenase-1 inhibition. However, the mechanism driving the concomitant cellular activation is unknown. We investigated the capacity of aspirin itself to provide this activation signal. Eosinophils were enriched from peripheral blood samples and activated with lysine ASA (LysASA). Parallel samples were stimulated with related non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs. Activation was evaluated as Ca+2 flux, secretion of cysteinyl leukotrienes (CysLT), and eosinophil derived neurotoxin (EDN) release. CD34+ progenitor-derived mast cells were also used to test the influence of aspirin on human mast cells with measurements of Ca+2 flux and PGD2 release. LysASA induced Ca+2 fluxes and EDN release, but not CysLT secretion from circulating eosinophils. There was no difference in the sensitivity or extent of activation between AERD and control subjects and sodium salicylate was without effect. Like eosinophils, aspirin was able to activate human mast cells directly through Ca+2 flux and PGD2 release. AERD is associated with eosinophils maturing locally in a high interferon (IFN)-γ milieu. As such, in additional studies, eosinophil progenitors were differentiated in the presence of IFN-γ prior to activation with aspirin. Eosinophils matured in the presence of IFN-γ displayed robust secretion of both EDN and CysLTs. These studies identify aspirin as the trigger of eosinophil and mast cell activation in AERD, acting in synergy with its ability to release cells from the anti-inflammatory constraints of PGE2.

Keywords: eosinophil, aspirin exacerbated respiratory disease, leukotriene, cyclooxygenase, mast cell

Introduction

Aspirin-exacerbated respiratory disease (AERD) is a distinct syndrome characterized by asthma, chronic sinusitis, nasal polyposis, and sensitivity to aspirin and other non-selective inhibitors of cyclooxygenase (COX) (1, 2). Patients with aspirin sensitivity experience a wide variety of symptoms ranging from nasal congestion, rhinorrhea, and wheezing to life-threatening asthma attacks within 2–3 hours of ingesting aspirin or other non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) (3–5). These reactions do not reflect an IgE-mediated allergic process. Instead, it is recognized that constitutive (COX-1-derived) prostaglandin (PG) E2 acts as an inhibitor of eosinophils and possibly mast cell activation and it is the removal of this “brake” by COX-1 inhibitors that permits cellular activation. Support of this concept is derived from recognition that exogenously administered PGE2 can protect the airway from reactivity to aspirin (6).

In particular, ingestion of NSAIDs leads to a surge in cysteinyl leukotrienes (CysLTs) secretion, reflecting the dramatic over-expression of leukotriene C4 synthase (LTC4S) by sinonasal and airway eosinophils, including an additional contribution by LTC4S-expressing platelets that are adherent to eosinophils and neutrophils in AERD (7–10). It is this surge in CysLT production that primarily drives the bronchospasm, as shown by the ability of LT modifiers to attenuate these reactions (11).

The role of concomitant mast cell activation in AERD is less clear than that for the role of eosinophil activation. Studies, including ours, have shown variable expression of mast cells in AERD tissue (8, 12, 13). In contrast, the intensity of the infiltration of the sinuses and lungs with eosinophils is a defining feature of this disease and comprehensively distinguishes AERD from either aspirin tolerant asthma or (aspirin tolerant) eosinophilic sinusitis (13–15). Furthermore, when identified, the mast cells observed in AERD modestly express LTC4S (8) and, as such, are likely minor contributors to the surge in CysLT production that defines these reactions. However, in addition to production of CysLTs and eosinophil-derived cationic peptides in AERD, NSAID challenges are associated with secretion of PGD2 and histamine indicative of some degree of mast cell activation (7, 16).

The traditional explanation that a decline in PGE2 concentrations drives the hypersensitivity reaction in AERD, however, is incomplete. In the absence of robust LTC4S expression, CysLT secretion would be minimal in asthmatics without AERD and healthy controls. However, an increase in other eosinophil degranulation products (e.g. cationic protein and eosinophil derived neurotoxin (EDN)) upon a decline in PGE2 would be expected. As such, the lack of such a response in these populations suggests the need for additional mechanisms driving the activation process.

Although the defining infiltration of eosinophils suggests a Th2 cytokine milieu, our recent studies demonstrate that AERD is also characterized by the expression of interferon (IFN)-γ and that it is the eosinophils themselves that are the primary source of this cytokine (17). Significantly, we demonstrated that amongst the classic signature Th1 and Th2 cytokines, only IFN-γ was able to upregulate LTC4S in eosinophils developing from hematopoietic progenitor cells, feature not shared with interleukin (IL)-4, IL-5, IL-13, or GM-CSF (17). As upregulated LTC4S in AERD is primarily a feature of sinonasal and lung – but not circulating – eosinophils (8, 15) and unpublished observations, we argued that thisa feature of eosinophils differentiating locally in the airway from the exuberant population of infiltrating precursors (CD34+IL-5Rα+ cells) (18, 19).

The current studies were therefore designed to assess direct activation of eosinophils and mast cells by aspirin and other NSAIDs through one of the off-target pathways ascribed to them (20, 21). In addition, we investigated the capacity of IFN-γ to license the ability of newly differentiated eosinophils to respond to aspirin (and other NSAIDs) with CysLT release.

Methods

Subjects

The study was approved by the University of Virginia Institutional Review Board for Health Science Research and all subjects gave their informed consent. Subjects with and without AERD were recruited for this study. AERD was diagnosed based upon clinical criteria and was defined by the presence of asthma and at least one hypersensitivity reaction, including urticaria, nasal congestion or shortness of breath within 2–3 hrs of ingestion of either aspirin or another non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug.

Reagents

Ketorolac was purchased from Hospira (Lake Forest, IL), sodium salicylate (NaSal) from Acros Organics (Geel, Belgium), lysine aspirin (LysASA) from Sanofi-Aventis (Athens, Greece) and celecoxib from Pfizer (New York, NY).

Cell culture

Peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) were isolated through Ficoll-Hypaque (Sigma) density centrifugation from blood obtained from subjects enrolled in the study. Eosinophils were enriched from granulocytes using negative magnetic affinity column purification (CD16−; Miltenyi Biotec, Auburn, CA) with >95% purity. Cells were suspended in complete RPMI1640 (Invitrogen) medium supplemented with 10% autologous serum.

Cellular activation

For all activation experiments, 1×106 cells in 0.5ml were exposed to LysASA, NaSal, ketorolac or celecoxib at concentrations ranging from 0.3 to 10 mM for 30 min after which supernatants were collected for ELISA's.

ELISA

PGD2 (Cayman), CysLT (Assay Designs, Ann Arbor, MI), and EDN (MBL, Nagoya, Japan) concentrations in culture supernatants were quantified by ELISA according to the manufacturer's instructions. The detection limits for the assays were 55.0 pg/ml for PGD2, 26.6 pg/ml for CysLT, and 0.62 ng/ml for EDN.

Ca+2 flux

Eosinophils were aliquoted in a 96-well dark-walled plate at 125,000 cells per well in 50 μl and allowed to settle for 60 min. Cells were either left untreated or stimulated with LysASA, NaSal, or ketorolac at concentrations ranging from 0.3 to 10 mM at 37°C. The calcium flux assay was performed using the Fluo-4 NW Calcium Assay Kit following manufacturer's instructions (Molecular Devices, Sunnyvale, CA). Briefly, 50μl of loading buffer supplemented with 5.0 mM probenecid (Sigma, St Louis, MO) was added to each well and incubated at 37°C for 30 min. Cytoplasmic [Ca+2]i was determined at an extinction wavelength of 494 nm and an emission wavelength of 516 nm using a Flexstation fluorescence spectrophotometer (Molecular Devices) with 20 μl of each stimulus added for a final volume of 120 μl. Each condition was set up in triplicate and the average of the three measurements used for analysis. ATP (300 μM) was used as a positive control. Data analyses were performed using GraphPad Prism 6 (GraphPad Software Inc, San Diego, CA). Additional studies were performed in the additional presence of EGTA (1 mM) to chelate extracellular sources of Ca+2.

Eosinophil progenitor activation

Peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) were isolated through Ficoll-Hypaque (Sigma) density centrifugation from blood obtained from healthy volunteers. CD34+ cells were enriched from PBMCs using positive magnetic affinity column purification (Miltenyi Biotec) and eosinophil progenitors were derived using the technique of Hudson et al. (22) by culturing purified CD34+ cells in complete medium (RPMI1640 and 10% FBS) supplemented with stem cell factor (SCF; 25 ng/ml; BD Biosciences), thymopoietin (TPO; 25 ng/ml; R&D System, Minneapolis, MN), Fms-like tyrosine kinase 3 (Flt3) ligand (25 ng/ml; BD Biosciences), IL-3 (25 ng/ml; BD Biosciences) and IL-5 (25 ng/ml; BD Biosciences) with or without IFN-γ (20 ng/ml; BD Bioscience) for 3 days and then cultured for an additional 3 weeks with just IL-3 and IL-5 (±IFN-γ). Cells were washed and fresh media and cytokines were applied weekly. Maturation was accessed as previously described (17) and cells were activated as described above.

Mast Cells. For studies involving mast cells, CD34+ cells isolated as described were cultured for 8 weeks with stem cell factor and IL-6 and, for the first week only, with IL-3 according to the methodology of Kirshenbaum et al (23, 24).

Statistical analyses

Data were contrasted between unstimulated and stimulated cells by Wilcoxon Rank Sum for nonparametric data analyses or paired t-test for parametric data. Normal and AERD cohorts were compared using unpaired t-tests. Statistical analyses were performed using GraphPad Prism 6.

Results

Eosinophil Ca+2 Flux

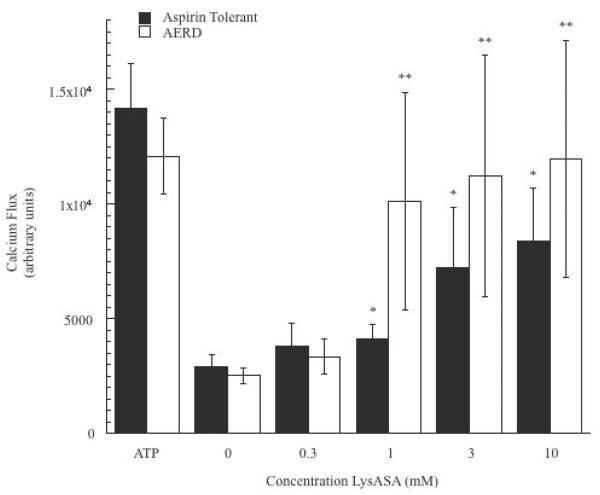

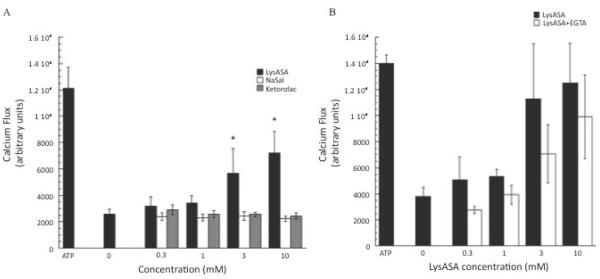

We evaluated the capacity of aspirin and other NSAIDs to directly activate enriched peripheral blood eosinophils, initially by examining induction of calcium fluxes. For these studies, we used the aspirin-like compound LysASA that retains the biological properties of aspirin while being water-soluble. Ca+2 fluxes were consistently observed at physiologically relevant concentrations for eosinophils in a dose-dependent manner (p<0.05; data from 12 subjects (6 each with and without AERD) are displayed in Figure 1. The presence of AERD made no statistically significant difference in either the extent of Ca+2 mobilization with eosinophils to LysASA or in sensitivity (EC50 = 2.1 mM for controls and 0.8 mM for AERD). The calcium flux studies were also performed with the related anti-inflammatory compounds NaSal, which retains many of the off target anti-inflammatory activities of aspirin but does not inhibit COX, and ketorolac, which is a non-selective COX inhibitor. Unlike LysASA, both NaSal and –unexpectedly – ketorolac were unable to induce calcium flux (Figure 2A). To determine whether the calcium mobilized in the assay was derived from intra- or extracellular stores, additional studies were performed in the presence of EGTA. Insignificant decreases in Ca+2 flux were observed (Figure 2B), suggesting that the main source of calcium was being derived from intracellular stores.

Figure 1. LyASA stimulation of eosinophils from AERD and non-AERD subjects.

Calcium mobilization assays were performed on eosinophils by plating 125,000 cells/well and incubating the cells with Fluo-4 NW wash dye mix supplemented with 5mM probenecid for 1 hr. Dose-response curves were generated by incubation of the cells increasing concentrations of LysASA (0.3–10mM) and measuring cytoplasmic calcium flux. ATP was used as a positive control. Data are presented as the mean±SEM of separate studies performed in triplicate (6 aspirin tolerant, 6 AERD subjects: *p<0.05 and **p<0.05 compared to unstimulated healthy control and AERD control, respectively).

Figure 2. Ca+2 flux of NSAID stimulated eosinophils.

Calcium mobilization assays were performed on eosinophils by plating 125,000 cells/well and incubating the cells with Fluo-4 NW wash dye mix supplemented with 5mM probenecid for 1 hr. A) Dose-response curves were generated by incubation of the cells increasing concentrations of LysASA, NaSal or ketorolac (0.3–10mM) and measuring cytoplasmic calcium flux. ATP was used as a positive control. Data are presented as the mean±SEM of separate studies performed in triplicate (n=9 LysASA and ketorolac, n=6 NaSal: *p<0.05 compared to unstimulated control). B) Dose-response curves were generated by incubation of the cells with increasing concentrations of LysASA (0.3–10mM) in the presence or absence 1mM EGTA and measuring cytoplasmic Ca+2 flux.

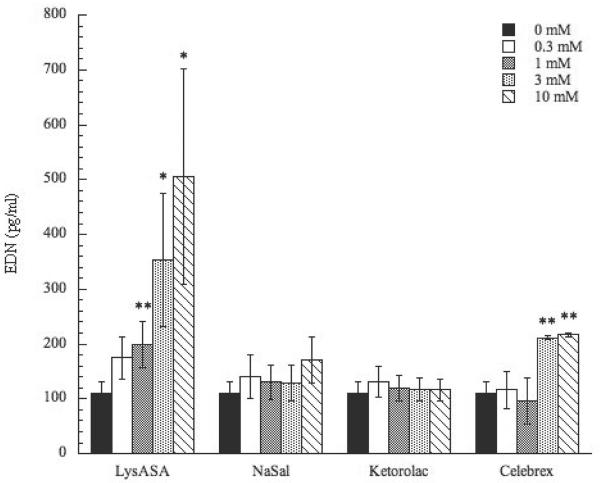

Eosinophil Degranulation

To investigate whether NSAID stimulation would lead to release of eosinophil-derived mediators, EDN and CysLT secretion was assessed. Incubation with LysASA in a dose-dependent fashion resulted in statistically significant increases of EDN secretion (p<0.05)(Figure 3). As with the Ca+2 flux, no differences were observed between AERD and control cohorts (data not shown). Further, no EDN release was observed after incubation with NaSal or ketorolac. However, incubation with celecoxib did result in release of EDN (p<0.01) at the 3 and 10 mM concentrations, though not as robust as LysASA (Figure 3). In contrast to the EDN results, LysASA did not increase CysLT secretion from these peripheral blood-derived eosinophils, again, even when obtained from AERD subjects (data not shown).

Figure 3. Activation of peripheral blood eosinophils by NSAIDs.

Eosinophils were purified from peripheral blood and stimulated in a dose-dependent fashion with LysASA, NaSal, ketorolac, or celecoxib (0.3–10mM) for 30 min. EDN was measured in supernatants and measured in ng/ml. Data are presented as the mean±SEM of 4–13 separate studies. *p<0.05; **p<0.01 as compared to unstimulated cells.

Influence of IFN-γ on aspirin activation of eosinophils derived from CD34+ progenitors

Circulating eosinophils display comparatively modest expression of LTC4S, even when derived from AERD subjects, compared to what is observed in their sinonasal tissue and lungs (8, 15) and unpublished observations. However, we have recently demonstrated that eosinophils matured in the additional presence of IFN-γ – as occurs locally in the sinonasal tissue and lungs of AERD patients – display upregulated LTC4S expression and markedly increased their release of CysLTs (and EDN) when activated with phorbol myristate acetate/ionomycin (17). We therefore queried whether eosinophils differentiated from CD34+ hematopoietic progenitor cells in the presence of IFN-γ would demonstrate CysLT secretion when exposed to LysASA. As with eosinophils obtained from circulating blood, eosinophils differentiated in the absence of IFN-γ (n=6) secreted EDN after exposure to LysASA (Figure 4A) but only modest secretion of CysLTs was observed (Figure 4B). The presence of IFN-γ during maturation significantly enhanced the capacity of in vitro-differentiated eosinophils to degranulate and release EDN (Figure 4A: p<0.0004 at the 1 and 10 mM concentrations). More importantly, the concomitant presence of IFN-γ led to significant induction of the capacity of these eosinophils to secrete CysLTs (Figure 4B; p<0.03 at the 1 and 10 mM concentrations).

Figure 4. Activation of eosinophils differentiated from hematopoietic precursors in the additional presence of IFN-γ.

CD34+-enriched hematopoietic progenitor cells were cultured for 3 days with SCF, TPO, Flt3L, IL-3, and IL-5 after which they were cultured for 3 additional weeks with just IL-3 and IL-5 with or without the additional presence of IFN-γ. Eosinophils matured from CD34+ progenitors were activated with or without calcium ionophore/PMA, LysASA (1 and 10 mM) or ketorolac (1 and 10 mM) for 30 minutes.

Supernatants were collected and A) EDN and B) CysLT levels quantified and measured in ng/ml or pg/ml, respectively. Data are presented as the mean±SEM of a minimum of 6 separate studies. ‡p=0.05, *p<0.0004, **p<0.03, ***p<0.002 as compared to unstimulated cells.

Ketorolac activation

AERD subjects react to aspirin and other non-selective NSAIDs including ketorolac (25, 26). We therefore interrogated the ability of this compound to activate CD34+ progenitor-derived eosinophils and, as with LysASA, observed significant CysLT release (Figure 4B). The activation induced by ketorolac at the 10 mM concentration was more pronounced than that observed with LysASA (p<0.002) and, as displayed in Figure 4A, was further enhanced when the cells were matured with IFN-γ.

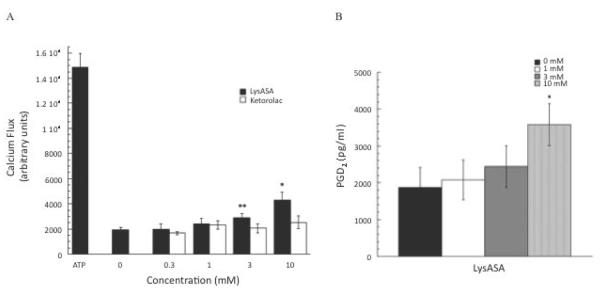

Aspirin activation of CD34+ progenitor-derived mast cells

Having demonstrated aspirin activation of eosinophils, we wanted to address whether similar activation pathways were induced in mast cells. As with the eosinophils, we initially investigated the capacity of these compounds to drive Ca+2 fluxes in mast cells differentiated from CD34+ progenitor cells. Similar to the results for eosinophils, LysASA was able to significantly (p<0.05) stimulate Ca+2 flux (Figure 5A). While ketorolac induced modest Ca+2 fluxes, the results were not significantly different than unstimulated cells (Figure 5A). Since aspirin/NSAID reactions in AERD are associated with PGD2 release, PGD2 secretion was measured after CD34+-derived mast cells were stimulated with LysASA. Similar to the Ca+2 flux data, PGD2 release was observed at the highest concentration of LysASA (Figure 5B; p<0.05).

Figure 5. Activation of CD34-differentiated mast cells.

A) Calcium mobilization assays were performed on CD34-derived mast cells as described. Dose-response curves were generated by incubation of the cells increasing concentrations of LysASA or ketorolac (0.3–10mM). ATP was used as a positive control. Data are presented as the mean±SEM of 3 separate studies performed in triplicate (*p<0.05, **p=0.08). B) CD34-derived mast cells were stimulated with LysASA (0.3–10mM) for 30 min. PGD2 release was measured in supernatants as pg/ml. Data are presented as the mean±SEM of 10 studies (p<0.03).

Discussion

AERD is characterized by eosinophilic infiltration into the upper (sinus and nasal polyp) and lower (bronchial) airway that is markedly greater than that observed in aspirin tolerant asthmatics (13–15) and these eosinophils are individually characterized by much higher expression of the rate limiting enzyme permitting CysLT synthesis, LTC4S (8). As a result when eosinophils are activated after ingestion of aspirin or other non-selective inhibitors of COX, there is a surge in CysLT secretion (27, 28). CysLT secretion is further enhanced by the distinct tendency of platelets to adhere to eosinophils and neutrophils in AERD and the transcellular conversion of LTA4 into CysLTs by the platelets (10). CysLTs underlie much of the symptomatic component of these anaphylactoid reactions, as demonstrated by the ability of leukotriene modifiers to greatly attenuate their presence and severity (15, 29, 30). While many cell types are capable and likely contribute to the CysLT production and inflammatory response in AERD, these studies focused on the contribution of these products by eosinophils and mast cells.

The stimulus driving eosinophil and mast cell activation is not known. In part, these reactions reflect the ability of PGE2 acting through the anti-inflammatory receptor EP2 to constrain cellular activation. Thus, co-administration of synthetic PGE2 prevents the bronchospastic response to aspirin challenge (6). This explanation, however, is incomplete. If a low PGE2 milieu is all that were required for eosinophil activation to occur, then eosinophil activation would also occur in all asthmatics and even in non-asthmatics, albeit in the relative absence of CysLT generation. This suggests the concomitant need for a positive signal driving eosinophil activation. Aspirin and other NSAIDs have numerous off target effects, independent of their ability to inhibit COX (20). Recently, as an example, aspirin was demonstrated to engage an L-type Ca+2 channel to promote cellular activation (21). We therefore posited that it is aspirin itself that is responsible for cellular activation in AERD.

Using peripheral blood eosinophils, induction of Ca+2 flux was measured following stimulation with LysASA (Figure 1). LysASA in a dose-dependent manner generated a Ca+2 flux with a maximal response observed at 10 mM, but significant changes also observed at pharmacologically meaningful concentrations. When aspirin tolerant and aspirin sensitive circulating eosinophils were compared, there was no difference in their responses to LysASA stimulation. Similar results were observed when we examined EDN secretion in response to LysASA (Figure 3). However, in addition to observing activation with control subjects, many other features of this LysASA-induced activation of circulating eosinophils was inconsistent with what is observed in AERD subjects including especially the absence of CysLT production, but also the failure to observe activation with ketorolac.

This induction of Ca+2 fluxes and EDN secretion by LysASA acting on eosinophils derived from control subjects was unexpected. There are numerous potential explanations for the failure to observe – even modest – hypersensitivity reactions in aspirin tolerant asthmatics and healthy controls. To some extent this reflects the relative dearth of eosinophils in these other conditions with several studies including ours (13, 15) demonstrating >10-fold fewer tissue eosinophils and, as such, the impact of eosinophil activation would be proportionately less. However, the more likely explanation is the relative impact of COX inhibitors in these conditions. PGE2 acts through the anti-inflammatory EP2 receptor to mediate its protective responses (6, 31). In AERD, the PGE2 synthetic pathway is suppressed and both constitutive tissue PGE2 concentrations and expression of the anti-inflammatory PGE2 receptor EP2 are diminished (15, 32, 33). Thus, AERD patients exist on the precipice of cellular activation with their borderline expression of PGE2 and EP2 such that even a modest decrease in PGE2 can have the observed catastrophic effects. This model is consistent with recent observations that in a murine model of AERD, knockout of the rate-limiting enzyme responsible for PGE2 synthesis, specifically mPGES-1 renders these mice susceptible to anaphylactoid reactions after exposure to aspirin (34)

A further explanation for lack of reactivity in control cohorts is that a large component of the syndrome induced by aspirin is driven by CysLTs as shown by the ability of LT modifiers to greatly attenuate the severity of reactions (29, 35). Interestingly, we did not observe CysLT secretion from eosinophils even when derived from the circulation of AERD subjects We recently demonstrated that AERD is characterized by a high tissue IFN-γ milieu and, in contrast to the Th2 signature cytokines (IL-3, IL-4, IL-5, IL-13, and GM-CSF), IFN-γ was uniquely capable of driving the expression of LTC4S and the secretion of CysLTs from eosinophils differentiated from CD34+ hematopoietic progenitor cells (17). AERD sinonasal and lung tissue is characterized by high numbers of eosinophilic hematopoietic progenitor (CD34+IL-5Rα+) cells (18, 19) that will mature in this presence of IFN-γ and acquire the ability to produce CysLTs; this would suggest that the robust CysLT production would be limited to airway – and not circulating – eosinophils. In the current studies, we therefore investigated whether eosinophils differentiated from progenitor cells in the presence of IFN-γ would recapitulate the sensitivity to aspirin displayed by tissue eosinophils in vivo in AERD. Not only was EDN release increased in IFN-γ stimulated eosinophil progenitors (Figure 4A), but consistent with their increased LTC4S expression, CysLT secretion was thereby also detected upon LysASA activation (Figure 4B). Importantly, activation was again also significant at lower, pharmacologically relevant, concentrations of LysASA.

Having observed activation by LysASA, we tested the ability of other NSAIDs to activate eosinophils. The absence of effects by NaSal on eosinophils on both Ca+2 flux (Figure 2A) and EDN release (Figure 3) indicates that the action by LysASA is not being mediated by the salicylate component (20), a result that is consistent with the ability of AERD patients to tolerate salicylates (36). In contrast, AERD patients are variably sensitive to non-selective NSAIDs capable of COX inhibition (37) including ketorolac (25, 26). In contrast to circulating eosinophils, ketorolac was able to activate newly differentiated eosinophils to stimulate CysLT release especially in the presence of IFN-γ (Figure 4B). Thus, IFN-γ exposure fully recapitulates the AERD phenotype by rendering these eosinophils responsive to ketorolac.

Finally, we addressed the ability LysASA to also activate mast cells. Although less prevalent (8, 12, 13), studies examining mediator release following aspirin challenge in AERD identified histamine, tryptase, and PGD2 generation demonstrating mast cell involvement (16, 38, 39). Using mast cells generated from CD34+ progenitors, we observed a dose-dependent increase in Ca+2 flux similar to that observed with eosinophils when the cells were stimulated with LysASA and a slight but non-significant increase with ketorolac (Figure 5A). Additionally, PGD2, secretion was increased after stimulation with LysASA (Figure 5B). Again, it was surprising that ketorolac failed to elicit a more robust response given its ability to cause reactions when given to AERD subjects. This, again, may reflect the inherent variability in sensitivity to NSAIDs and, that as with eosinophils, the mast cells need to be matured in the presence of an additional agent, such as IFN-γ, to render the cells fully responsive to ketorolac.

In summary, our data demonstrate the ability of aspirin to directly activate eosinophils and mast cells causing the release of inflammatory mediators. Further, the concomitant presence of high sinonasal and asthma tissue concentrations of IFN-γ with infiltrating eosinophil progenitors in AERD subjects, along with the present study's demonstration of the ability of IFN-γ to “sensitize” the eosinophil towards CysLT release on activation, explains part of the surge of CysLT production and release seen on exposure to aspirin. While this activation can occur in aspirin tolerant asthmatics and non-asthmatics, it is constrained in these subjects by their continued expression of sufficient PGE2 to inhibit cellular activation acting through their much higher expression of the anti-inflammatory PGE2 receptor, EP2.

Acknowledgments

Supported by NIH grants R01-AI47737 and P01-AI50989

Abbreviations

- AERD

aspirin exacerbated respiratory disease

- ASA

aspirin

- COX

cyclooxygenase

- CysLT

cysteinyl leukotriene

- EDN

eosinophil derived neurotoxin

- ELISA

enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay

- IFN

interferon

- IL

interleukin

- LTC4S

leukotriene C4 synthase

- LysASA

lysine aspirin

- NaSal

sodium salicylate

- NSAID

non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug

- PBMC

peripheral blood mononuclear cells

- PG

prostaglandin

References

- 1.Steinke JW, Huyett P, Payne SC, Negri J, Borish L. Cytokines and lymphocytes in eosinophilic sinusitis: prominent role for interferon-γ. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2011;132:856–865. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2013.05.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mascia K, Borish L, Patrie J, Hunt J, Phillips CD, Steinke JW. Chronic hyperplastic eosiniphilic sinusistis as a predictor of aspirin-exacerbated respiratory disease. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2005;94:652–657. doi: 10.1016/S1081-1206(10)61323-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Szczeklik A, Stevenson DD. Aspirin-induced asthma: Advances in pathogenesis and management. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 1999;104:5–13. doi: 10.1016/s0091-6749(99)70106-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Szczeklik A, Nizankowska E. Clinical features and diagnosis of aspirin induced asthma. Thorax. 2000;55:S42–S44. doi: 10.1136/thorax.55.suppl_2.S42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Berges-Gimeno MP, Simon RA, Stevenson DD. The natural history and clinical characteristics of aspirin-exacerbated respiratory disease. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2002;89:474–478. doi: 10.1016/S1081-1206(10)62084-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sestini P, Armetti L, Gambaro G, Pieroni MG, Refini RM, Sala A, Vaghi A, Folco GC, Bianco S, Robuschi M. Inhaled PgE2 prevents aspirin-induced bronchoconstriction and urinary LTE4 excretion in aspirin-sensitive asthma. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1996;153:572–575. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.153.2.8564100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sladek K, Szczeklik A. Cysteinyl leukotrienes overproduction and mast cell activation in aspirn-provoked bronchospasm in asthma. Eur Respir J. 1993;6:391–399. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cowburn AS, Sladek K, Soja J, Adamek L, Nizankowska E, Szczeklik A, Lam BK, Penrose JF, Austen KF, Holgate ST, Sampson AP. Overexpression of leukotriene C4 synthase in bronchial biopsies from patients with aspirin-intolerant asthma. J Clin Invest. 1998;101:834–846. doi: 10.1172/JCI620. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Daffern PJ, Muilenburg D, Hugli TE, Stevenson DD. Association of urinary leukotriene E4 excretion during aspirin challenges with severity of resiratory responses. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 1999;104:559–564. doi: 10.1016/s0091-6749(99)70324-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Laidlaw TM, Kidder MS, Bhattacharyya N, Xing W, Shen S, Milne GL, Castells MC, Chhay H, Boyce JA. Cysteinyl leukotriene overproduction in aspirin-exacerbated respiratory disease is driven by platelet-adherent leukocytes. Blood. 2012;119:3790–3798. doi: 10.1182/blood-2011-10-384826. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dahlen B, Nizankowska E, Szczeklik A. Benefits from adding the 5-lipoxygenase inhibitor zileuton to conventional therapy in aspirin-intolerant asthmatics. Am J Respir Critc Care Med. 1998;157:1187–1194. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.157.4.9707089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kamil A, Ghaffar O, Lavigne F, Taha R, Renzi PM, Hamid Q. Comparison of inflammatory cell profile and Th2 cytokine expression in the ethmoid sinuses, maxillary sinuses, and turbinates of atopic subjects with chronic sinusitis. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1998;18:804–809. doi: 10.1016/S0194-5998(98)70273-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Payne SC, Early SB, Huyett P, Han JK, Borish L, Steinke JW. Evidence for distinct histologic profile of nasal polyps with and without eosinophilia. Laryngoscope. 2011;121:2262–2267. doi: 10.1002/lary.21969. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bachert C, Wagenmann M, Hauser U, Rudack C. IL-5 synthesis is upregulated in human nasal polyp tissue. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 1997;99:837–842. doi: 10.1016/s0091-6749(97)80019-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Perez-Novo CA, Watelet JB, Claeys C, van Cauwenberge P, Bachert C. Prostaglandin, leukotiene, and lipoxin balance in chronic rhinosinusitis with and without nasal polyposis. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2005;115:1189–1196. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2005.02.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fischer AR, Rosenberg MA, Lilly CM, Callery JC, Rubin P, Cohn J, White MV, Igarashi Y, Kaliner MA, Drazen JM, Israel E. Direct evidence for a role of the mast cell in the nasal response to aspirin n aspirin-sensitive asthma. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 1994;94:1046–1056. doi: 10.1016/0091-6749(94)90123-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Steinke JW, Liu L, Huyett P, Negri J, Payne SC, Borish L. Prominent Role of Interferon-γ in Aspirin-Exacerbated Respiratory Disease. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2013;132:856–865. e853. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2013.05.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kim YK, Uno M, Hamilos DL, Beck L, Bochner B, Schleimer RP, Denburg JA. Immunolocalization of CD34 in nasal polyp. Effect of topical corticosteroids. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 1999;20:388–397. doi: 10.1165/ajrcmb.20.3.3060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Denburg JA. Haemopoietic mechanisms in nasal polyposis and asthma. Thorax. 2000;55:S24–S25. doi: 10.1136/thorax.55.suppl_2.S24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tegeder I, Pfeilschifter J, Geisslinger G. Cyclooxygenase-independent actions of cyclooxygenase inhibitors. FASEB J. 2001;15:2057–2072. doi: 10.1096/fj.01-0390rev. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Suzuki Y, Ra C. Analysis of the mechanism for the development of allergic skin inflammation and the application for its treatment: aspirin modulation of IgE-dependent mast cell activation: role of aspirin-induced exacerbation of immediate allergy. J Pharmacol Sci. 2009;110:237–244. doi: 10.1254/jphs.08r32fm. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hudson SA, Herrmann H, Du J, Cox P, Haddad el B, Butler B, Crocker PR, Ackerman SJ, Valent P, Bochner BS. Developmental, malignancy-related, and cross-species analysis of eosinophil, mast cell, and basophil siglec-8 expression. J Clin Immunol. 2011;31:1045–1053. doi: 10.1007/s10875-011-9589-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kirshenbaum AS, Goff JP, Semere T, Foster B, Scott LM, Metcalfe DD. Demonstration that human mast cells arise from a progenitor cell population that is CD34(+), c-kit(+), and expresses aminopeptidase N (CD13) Blood. 1999;94:2333–2342. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Laidlaw TM, Steinke JW, Tinana AM, Feng C, Xing W, Lam BK, Paruchuri S, Boyce JA, Borish L. Characterization of a novel human mast cell line that responds to stem cell factor and expresses functional FcepsilonRI. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2011;127:815–822. e811–815. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2010.12.1101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.White A, Bigby T, Stevenson D. Intranasal ketorolac challenge for the diagnosis of aspirin-exacerbated respiratory disease. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2006;97:190–195. doi: 10.1016/S1081-1206(10)60012-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lee RU, White AA, Ding D, Dursun AB, Woessner KM, Simon RA, Stevenson DD. Use of intranasal ketorolac and modified oral aspirin challenge for desensitization of aspirin-exacerbated respiratory disease. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2010;105:130–135. doi: 10.1016/j.anai.2010.05.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Christie PE, Tagari P, Ford-Hutchinson AW, Charlesson S, Chee P, Arm JP, Lee TH. Urinary leukotriene E4 concentrations increase after aspirin challenge in aspirin-sensitive asthmatic subjects. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1991;143:1025–1029. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm/143.5_Pt_1.1025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Szczeklik A, Sladek K, Dworski R, Nizankowska E, Soja J, Sheller J, Oates J. Bronchial aspirin challenge causes specific eicosanoid response in aspirin-sensitive asthmatics. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1996;154:1608–1614. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.154.6.8970343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Dahlen B. Treatment of aspirin-intolerant asthma with antileukotrienes. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2000;161:S137–S141. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.161.supplement_1.ltta-27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Steinke JW, Bradley D, Arango P, Crouse CD, Frierson H, Kountakis SE, Kraft M, Borish L. Cytseinyl leukotriene expression in chronic hyperplastic sinusitis-nasal polyposis: Importance to eosinophilia and asthma. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2003;111:342–349. doi: 10.1067/mai.2003.67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Steinke JW. Editorial: Yin-Yang of EP receptor expression. J Leuk Biol. 2012;92:1129–1131. doi: 10.1189/jlb.0812374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kowalski ML, Pawliczak R, Wozniak J, Siuda K, Poniatowska M, Iwaszkiewicz J, Kornatowski T, Kaliner MA. Differential metabolism of arachidonic acid in nasal polyp epithelial cells cultured from aspirin-sensitive and aspirin-tolerant patients. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2000;161:391–398. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.161.2.9902034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ying S, Meng Q, Scadding G, Parikh A, Corrigan CJ, Lee TH. Aspirin-sensitive rhinosinusitis is associated with reduced E-prostanoid 2 receptor expression on nasal mucosal inflammatory cells. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2006;117:312–318. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2005.10.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Liu T, Laidlaw TM, Katz HR, Boyce JA. Prostaglandin E2 deficiency causes a phenotype of aspirin sensitivity that depends on platelets and cysteinyl leukotrienes. Proc Nat Acad Sci USA. 2013;110:16987–16992. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1313185110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Christie PE, Smith CM, Lee TH. The potent and selective sulfidopeptide leukotriene antagonists, SK&F 104353, inhibits aspirin-induced asthma. Am Rev Resir Dis. 1991;144:957–958. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm/144.4.957. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Stevenson DD, Hougham AJ, Schrank PJ, Goldlust MB, Wilson RR. Salsalate cross-sensitivity in aspirin-sensitive patients with asthma. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 1990;86:749–758. doi: 10.1016/s0091-6749(05)80179-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mathison DA, Stevenson DD. Hypersensitivity to nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs: indications and methods for oral challenges. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 1979;64:669–674. doi: 10.1016/0091-6749(79)90036-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Higashi N, Taniguchi M, Mita H, Osame M, Akiyama K. A comparative study of eicosanoid concentrations in sputum and urine in patients with aspirinintolerant asthma. Clin Exp Allergy. 2002;32:1484–1490. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2745.2002.01507.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bochenek G, Nagraba K, Nizankowska E, Szczeklik A. A controlled study of 9alpha,11beta-PGF2 (a prostaglandin D2 metabolite) in plasma and urine of patients with bronchial asthma and healthy controls after aspirin challenge. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2003;111:743–749. doi: 10.1067/mai.2003.1387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]