Abstract

Background

Smoking increases the risk of morbidity and mortality and is particularly harmful to HIV-infected people.

Purpose

To explore smoking trends and longitudinal factors associated with smoking cessation and recidivism among participants in the Women's Interagency HIV Study.

Methods

From 1994 through 2011, 2,961 HIV-infected and 981 HIV-uninfected women were enrolled and underwent semi-annual interviews and specimen collection. Smoking prevalence was evaluated annually and risk factors associated with time to smoking cessation and recidivism were analyzed in 2013 using survival models.

Results

The annual cigarette smoking prevalence declined from 57% in 1995 to 39% in 2011 (p-trend<0.0001). Among smokers, factors significantly associated with a longer time to smoking cessation included less education, alcohol use, having health insurance, >10-year smoking duration, self-reported poor health rating, and having hypertension. Pregnancy in the past 6 months was associated with a shorter time to cessation. Among HIV-infected women, additional risk factors for longer time to cessation included lower household income, use of crack/cocaine/heroin, CD4 cell count ≤200, and highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART) use. Predictors of smoking recidivism included marijuana use, enrollment in 1994–1996, and not living in one's own place. Among HIV-infected women, enrollment in 2001-2002 and crack/cocaine/heroin use were associated with a shorter time to recidivism, whereas older age and HAART use were associated with a longer time to recidivism.

Conclusions

Despite declining rates of cigarette smoking, integrated interventions are needed to help women with and at risk for HIV infection to quit smoking and sustain cessation.

Introduction

The harmful health effects of cigarette smoking include an increased risk of developing cancer, heart disease, infections, and chronic pulmonary disease.1,2 Although smokers are also at risk for premature death,3 smoking cessation can reduce and sometimes reverse this excess risk.4–6 Smoking can be particularly harmful to HIV-infected individuals, who have an increased risk of mortality, cardiovascular disease, non-AIDS cancers, chronic obstructive lung disease, and pneumonia compared to HIV–infected never smokers.7–10

The use of antiretroviral therapy (ART) to treat HIV infection has dramatically reduced HIV-related morbidity and mortality, resulting in HIV-infected individuals reaching ages at which smoking-related disease rapidly increases.11 The combination of longevity, prolonged immunosuppression, and increasing number of pack-years of smoking puts smokers with HIV/AIDS at a heightened risk for tobacco-related morbidity and mortality.10 Thus, smoking-cessation programs are extremely important to maintain the health benefits of HIV treatment.

Little is known about smoking cessation among HIV-infected individuals. One large study reported that HIV-infected patients who quit smoking reduced their risk of cardiovascular disease and that this reduction increased with time since cessation of smoking.12 A smoking-cessation intervention conducted in a Swiss cohort study found that HIV-infected participants who were middle-aged, injection drug users, had psychiatric problems, or high alcohol consumption were less likely to stop smoking.13

In the Women's Interagency HIV Study (WIHS), a multicenter cohort study of HIV-1 infection in women conducted at six centers in the U.S, 72% of the HIV-infected and at-risk HIV–uninfected women are current (48%) or former (24%) cigarette smokers, a considerably higher prevalence than the national population rate.14 A 10-year assessment of smoking cessation in the WIHS found that the odds of tobacco cessation were higher among participants with more years of education and among Hispanic compared with non-Hispanic Black women.15 Cessation was lower in current or former illicit drug users and women reporting a higher daily number of cigarettes at baseline.15 This previous WIHS analysis evaluated baseline characteristics as predictors of smoking cessation among women only recruited in the first enrollment wave of the study (1994–1995) and did not include more recently enrolled participants or analyze predictors of recidivism or time-updated factors during study follow-up.

The current study includes participants from all three WIHS enrollment waves (1994–1995, 2001–2002, and 2011) and investigates time-updated factors as predictors. The aims of this investigation were to (1) calculate the annual smoking prevalence from 1994–2011; (2) assess predictors associated with time to self–reported sustained (>12 months) smoking cessation; and (3) measure risk factors associated with time to recidivism (self-reported resumption of smoking) among sustained quitters of smoking. By identifying predictors of smoking cessation and recidivism, these factors can be synthesized with conceptual models to tailor interventions for HIV-infected and at-risk women.

Methods

Study Population

This study included HIV-infected and HIV-uninfected participants in the WIHS. The WIHS methods, baseline characteristics, and participant retention rates have been described previously.16–19 To summarize, between October 1994 and November 1995, 2,054 HIV-infected and 569 uninfected women were enrolled (wave 1). A second enrollment wave, between October 2001 and September 2002, added 737 HIV-infected and 406 uninfected women. A third enrollment wave began January 2011, and 170 HIV-infected and six uninfected women enrolled through September 30, 2011. The HIV-infected women in the WIHS cohort reflect the race/ethnicity, HIV exposure groups, and ages of women with HIV/AIDS in the U.S.17 Study protocols were approved by the IRBs at all sites and informed consent was obtained.

Semiannually, WIHS participants were interviewed, had blood collected, and underwent a physical examination. Among HIV-infected women, blood was tested for CD4+ lymphocyte counts and HIV RNA levels. At each study visit, women were asked detailed information about their smoking history. The selection of factors associated with smoking cessation and recidivism in this investigation were guided by prior studies in the WIHS15 and other populations of HIV-infected adults.13,20 In addition, we included health-related factors that have been shown to be associated with smoking and cessation in women.21,22

Measures

In the survival time analyses, baseline covariates included race/ethnicity, age, number of years of smoking, WIHS locale (California, Illinois, New York, or District of Columbia), enrollment wave, and HIV status (excluding HIV seroconverters). All other covariates for the survival time analyses were time updated and obtained for the 6-month period immediately preceding the visit in which the outcome was ascertained—the first sustained quit visit or last non-quit visit for the time to cessation analyses, and the first recidivism visit or last sustained quit visit for the time to recidivism analyses. This ensured that the predictors preceded the event and were data lagged one semi-annual visit. These covariates included: educational attainment, living situation, employment, household income, place of residence, health insurance status assessed dichotomously as yes or no and as type of health insurance, alcohol and drug use in the past 6 months, the Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression Scale (CES-D) score dichotomized as >22 and yes or no,23,24 any hospitalization in the past 6 months, self-reported health rating on a 5-point scale ranging from 1=excellent to 5=poor,25 pregnancy in the past 6 months, child care responsibility in the past 6 months (children aged <18 years in household or care), hypertension (defined as measured systolic blood pressure ≥140, diastolic blood pressure >90, self-reported hypertension, or self–reported antihypertensive medication use), diabetes (defined as measured fasting glucose ≥126 mg/dL, hemoglobin A1C >6.5%, self-reported diabetes, or self-reported use of medications for diabetes), and cervical intraepithelial neoplasia (defined as cytologic or histologic cervical intraepithelial neoplasia-1 or more severe). In regression models that only included HIV-infected women, time-lagged CD4 cell count, HIV viral load, and use of ART were also assessed. In the unadjusted models, we also considered time-updated covariates at the prior 6-month visit (the 6–12-month interval preceding the sustained cessation visit) to see if the factors for initial cessation differed from those for sustained cessation.

The log-normal survival models assumed that the hazard function has a log-normal shape with two parameters (mean and dispersion) that were estimated from the data.26 Covariate effects were shown as a time ratio (TR), rather than a HR, and thus have an interpretation on the time scale. Factors usually termed “risky” or harmful will be associated with TR>1 for the time to cessation analysis but TR<1 for the time to smoking recidivism outcome.

Statistical Analysis

Yearly smoking prevalence was calculated as the number of women who reported smoking cigarettes divided by the number of women interviewed. The prevalence was further stratified by birth cohort and HIV status. The Cochran–Mantel–Haenszel test was used to measure differences across strata. The Cochran–Armitage trend test was used to assess changes in the annual prevalence by calendar year.

Two separate survival analyses were performed: time from baseline smoking to sustained (≥12 months) cessation and time from sustained cessation to recidivism (relapse). We defined recidivism as having reported resumption of smoking and a date that they resumed smoking. Time to cessation was calculated from date of the baseline smoking visit to the date of the first sustained quit visit. Women who did not quit were censored at the date of the last follow-up visit. This analysis included all women who reported current cigarette smoking at their baseline study visit and had at least two follow-up visits. Time to recidivism (first relapse to smoking) was measured among women reporting current cigarette use at study baseline, as the time from first sustained quit visit to the date of first resumption of smoking visit. Participants who did not relapse during follow-up were censored at the date of the last follow-up visit. This analysis included all participants who reported sustained cessation ≥12 months during WIHS study follow-up and had at least one post-sustained cessation follow-up visit.

Kaplan–Meier survival analyses measured median and mean time to cessation and time to recidivism in years. Factors affecting time to outcome of cessation or recidivism were evaluated using parametric survival models, assuming a log-normal distribution (accelerated failure time).26 In the accelerated failure time model, the effect of a covariate is expressed as either accelerating (shortening) or decelerating (lengthening) time to the event of interest. Covariates with statistical significance at p<0.05 in unadjusted models were entered into exploratory multivariate models for the respective outcomes. The final adjusted models were developed using a manual stepwise backward elimination process. Statistical analyses were performed in 2013 using SAS® software, version 9.3 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary NC).

Results

Smoking Prevalence Between 1995 and 2011

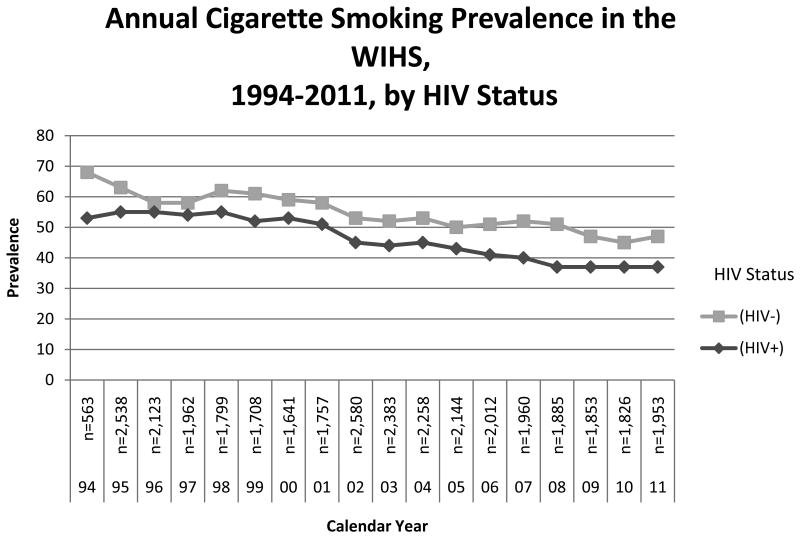

The annual cigarette smoking prevalence declined over time in the WIHS, from a high of 57% in 1995 to 39% in 2011 (trend test p<0.0001). Differences in annual smoking prevalence were also observed by birth cohort, with both the oldest (birth years 1920–1939) and youngest (birth years 1970–1985) birth cohorts having a lower smoking prevalence than those born between 1940–1969 (p<0.05, Figure 1). HIV-infected women had a lower prevalence of smoking compared with HIV-uninfected women (p<0.05, Figure 2).

Figure 1. Annual cigarette smoking prevalence in the WIHS, 1994–2011, by birth cohort WIHS, Women's Interagency HIV Study.

Figure 2. Annual cigarette smoking prevalence in the WIHS, 1994–2011, by HIV status WIHS, Women's Interagency HIV Study.

Smoking Cessation

Among the 1,622 WIHS participants who reported smoking cigarettes at their baseline study visit and had complete data on all follow-up study variables, 316 (19.4%) women subsequently reported sustained smoking cessation during study follow-up (median=16.5 years, mean=13.7 years). In adjusted analysis, factors significantly associated with a longer time to cessation (TR>1, Table 1) included socioeconomic factors (lower education and having health insurance), behavioral factors (higher number of years smoking cigarettes and alcohol consumption) and biological factors (a fair to poor self–reported health rating and history of hypertension). Having been pregnant in the past 6 months was significantly associated with a shorter time to cessation (TR<1). When time-lagged covariates in the 6–12-month period prior to sustained cessation were assessed (data not shown), the results were similar. When health insurance was assessed, either as a dichotomous variable (yes or no) or as a categorical variable (none, public, private, or other), in both instances having health insurance was associated with longer time to cessation.

Table 1. Time from baseline smoking to cessation among current and former cigarette smokers.

| Kaplan-Meier | Unadjusted log-normal | Adjusted log-normal | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristic | M | Median | n total | n quit | time ratio (95% CI) | time ratio (95% CI) |

| HIV statusa | ||||||

| HIV-uninfected | 13.2 | N/A | 430 | 84 | 1.00 (ref) | |

| HIV-infected | 13.6 | 16.5 | 1192 | 232 | 1.00 (0.74, 1.35) | |

| Statea | ||||||

| California | 13.4 | 16.5 | 521 | 110 | 0.82 (0.60, 1.12) | |

| District of Columbia | 11.9 | N/A | 182 | 31 | 1.13 (0.75, 1.71) | |

| Illinois | 13.5 | N/A | 250 | 43 | 1.14 (0.72, 1.82) | |

| New York | 12.4 | N/A | 669 | 132 | 1.00 (ref) | |

| Age group, yearsa | ||||||

| 18–29 | 13.3 | 16.5 | 290 | 66 | 1.00 (ref) | |

| 30–39 | 13.7 | N/A | 758 | 144 | 1.16 (0.84, 1.59) | |

| 40–49 | 12.4 | N/A | 505 | 91 | 1.21 (0.86, 1.70) | |

| ≥50 | 10.6 | N/A | 69 | 15 | 0.86 (0.44, 1.70) | |

| Enrollment wavea | ||||||

| 1994–1995 | 13.7 | 16.5 | 1201 | 235 | 1.00 (ref) | |

| 2001–2002 | 8.5 | N/A | 415 | 81 | 0.83 (0.62, 1.13) | |

| 2011 | N/A | N/A | 6 | 0 | N/A | |

| Race/ethnicitya | ||||||

| African American | 13.9 | 16.5 | 1060 | 191 | 1.00 (ref) | |

| Latina | 7.8 | N/A | 90 | 24 | 0.46 (0.27, 0.78) | |

| Other | 13.3 | N/A | 233 | 53 | 0.76 (0.52, 1.10) | |

| White | 12.3 | N/A | 239 | 48 | 0.78 (0.53, 1.14) | |

| Living with partner | ||||||

| Yes | 13.0 | 16.5 | 424 | 101 | 0.78 (0.58, 1.05) | |

| No | 13.5 | N/A | 1099 | 215 | 1.00 (ref) | |

| Educational attainment | ||||||

| <High school | 14.0 | 16.5 | 686 | 117 | 1.55 (1.11, 2.15) | 1.81 (1.15, 2.85) |

| High school | 12.5 | N/A | 510 | 101 | 1.26 (0.90, 1.78) | 1.20 (0.75, 1.90) |

| >High school | 12.5 | N/A | 424 | 98 | 1.00 (ref) | 1.00 (ref) |

| Employed | ||||||

| Yes | 11.9 | N/A | 353 | 107 | 0.46 (0.34, 0.62) | |

| No | 14.1 | 16.5 | 1260 | 205 | 1.00 (ref) | |

| Yearly household income | ||||||

| ≤$12,000 | 14.0 | 16.5 | 998 | 166 | 1.80 (1.37, 2.37) | |

| >$12,000 | 12.2 | N/A | 512 | 147 | 1.00 (ref) | |

| Health insurance | ||||||

| Yes | 13.9 | 16.5 | 1434 | 258 | 3.03 (2.08, 4.41) | 3.16 (1.89, 5.27) |

| No | 7.4 | N/A | 180 | 58 | 1.00 (ref) | 1.00 (ref) |

| Lives in their own place | ||||||

| Yes | 13.6 | 16.5 | 1229 | 256 | 0.90 (0.65, 1.25) | |

| No | 13.8 | N/A | 389 | 60 | 1.00 (ref) | |

| Number of years smoked a | ||||||

| <10 | 12.4 | 16.5 | 324 | 93 | 1.00 (ref) | 1.00 (ref) |

| 10–19 | 12.4 | N/A | 593 | 100 | 2.24 (1.58, 3.18) | 1.98 (1.22, 3.20) |

| ≥20 | 13.8 | N/A | 702 | 123 | 2.12 (1.51, 2.97) | 1.29 (0.80, 2.08) |

| Depressive symptoms (CESD) | ||||||

| <23 | 13.2 | N/A | 985 | 201 | 1.00 (ref) | |

| >23 | 14.2 | 16.5 | 469 | 68 | 1.15 (0.82, 1.60) | |

| Alcohol use | ||||||

| None | 13.0 | N/A | 894 | 205 | 1.00 (ref) | 1.00 (ref) |

| 1–6 drinks/week | 14.0 | 16.5 | 497 | 91 | 1.41 (1.05, 1.88) | 1.89 (1.26, 2.83) |

| >6 drinks/week or >3 in 1 sitting | 7.9 | N/A | 193 | 17 | 2.48 (1.50, 4.12) | 3.60 (1.78, 7.28) |

| Marijuana use | ||||||

| Yes | 12.6 | N/A | 352 | 50 | 1.51 (1.07, 2.13) | |

| No | 13.4 | 16.5 | 1238 | 266 | 1.00 (ref) | |

| Crack/cocaine/heroin use | ||||||

| Yes | 13.9 | N/A | 270 | 20 | 2.92 (1.82, 4.69) | |

| No | 13.3 | 16.5 | 1320 | 296 | 1.00 (ref) | |

| Health rating (self-report) | ||||||

| Good to excellent | 13.4 | 16.5 | 757 | 156 | 1.00 (ref) | 1.00 (ref) |

| Fair to poor | 13.1 | N/A | 518 | 56 | 2.16 (1.43, 3.26) | 1.66 (1.11, 2.47) |

| Hospitalized in past 6 months | ||||||

| Yes | 11.9 | N/A | 448 | 61 | 1.43 (1.03, 1.98) | |

| No | 13.5 | 16.5 | 1168 | 255 | 1.00 (ref) | |

| Pregnant in past 6 months | ||||||

| Yes | 7.7 | 9.2 | 35 | 16 | 0.25 (0.12, 0.54) | 0.21 (0.08, 0.59) |

| No | 13.6 | 16.5 | 1382 | 264 | 1.00 (ref) | 1.00 (ref) |

| Childcare responsibilities | ||||||

| Yes | 13.9 | 16.5 | 416 | 77 | 1.06 (0.75, 1.49) | |

| No | 13.6 | N/A | 1070 | 196 | 1.00 (ref) | |

| Hypertension | ||||||

| Yes | 14.7 | 16.5 | 606 | 83 | 2.48 (1.86, 3.29) | 2.28 (1.51, 3.46) |

| No | 12.9 | N/A | 1015 | 233 | 1.00 (ref) | 1.00 (ref) |

| Diabetes | ||||||

| Yes | 12.3 | N/A | 262 | 68 | 0.88 (0.63, 1.25) | |

| No | 13.7 | 16.5 | 1357 | 248 | 1.00 (ref) | |

| Cervical intraepithelial neoplasia | ||||||

| Yes | 12.2 | N/A | 206 | 25 | 1.4 (0.89, 2.22) | |

| No | 13.6 | 16.5 | 1254 | 261 | 1.00 (ref) | |

Note: Boldface indicates p<0.05.

Baseline covariates.

CESD, Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression Scale; N/A, not applicable

In adjusted analysis among HIV-infected women only, factors significantly associated with a longer time to cessation (TR>1, Table 2) included lower household income, having health insurance, higher alcohol consumption, use of cocaine/crack/heroin, history of hypertension, use of highly active ART (HAART), and CD4 cell counts <200, whereas having been pregnant in the past 6 months was associated with a shorter time to cessation (TR<1). When time-lagged covariates in the 6–12-month period prior to sustained cessation among the HIV-infected women were assessed (data not shown), the results were similar. Once again, whether health insurance was dichotomized or categorized, having health insurance was associated with a longer time to cessation.

Table 2.

Time from baseline smoking to cessation among current and former HIV-infected cigarette smokers

| Kaplan-Meier | Unadjusted log-normal | Adjusted Log-normal | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristic | M | Median | n total | n quit | time ratio (95% CI) | time ratio (95% CI) |

| Statea | ||||||

| California | 13.8 | 16.5 | 370 | 71 | 0.93 (0.65, 1.33) | |

| District of Columbia | 11.6 | N/A | 133 | 27 | 0.95 (0.58, 1.57) | |

| Illinois | 12.1 | N/A | 203 | 40 | 0.92 (0.60, 1.42) | |

| New York | 12.4 | N/A | 486 | 94 | 1.00 (ref) | |

| Age group, yearsa | ||||||

| 18–29 | 13.9 | 16.5 | 173 | 33 | 1.00 (ref) | |

| 30–39 | 13.6 | N/A | 580 | 114 | 0.87 (0.60, 1.28) | |

| 40–49 | 12.2 | N/A | 388 | 74 | 0.90 (0.61, 1.33) | |

| ≥50 | 10.5 | N/A | 51 | 11 | 0.69 (0.32, 1.50) | |

| Recruitment wavea | ||||||

| 1994–1995 | 13.7 | 16.5 | 932 | 185 | 1.00 (ref) | |

| 2001–2002 | 8.1 | N/A | 254 | 47 | 0.92 (0.64, 1.32) | |

| 2011 | N/A | N/A | 6 | 0 | ||

| Race/ethnicitya | ||||||

| African American | 13.7 | 16.5 | 800 | 149 | 1.00 (ref) | |

| Latina | 5.0 | N/A | 58 | 12 | 0.64 (0.33, 1.24) | |

| Other | 13.4 | N/A | 162 | 36 | 0.86 (0.56, 1.31) | |

| White | 12.4 | N/A | 172 | 35 | 0.88 (0.57, 1.36) | |

| Living with partner | ||||||

| Yes | 12.8 | 16.5 | 307 | 74 | 0.72 (0.52, 0.99) | |

| No | 13.6 | N/A | 816 | 158 | 1.00 (ref) | |

| Educational attainment | ||||||

| <High school | 14.0 | 16.5 | 510 | 84 | 1.63 (1.13, 2.35) | |

| High school | 12.5 | N/A | 379 | 75 | 1.34 (0.91, 1.96) | |

| >High school | 12.4 | N/A | 302 | 73 | 1.00 (ref) | |

| Employed | ||||||

| Yes | 11.7 | N/A | 206 | 65 | 0.48 (0.33, 0.69) | |

| No | 14.0 | 16.5 | 978 | 163 | 1.00 (ref) | |

| Yearly household income | ||||||

| ≤$12,000 | 14.0 | 16.5 | 759 | 122 | 1.92 (1.41, 2.62) | 1.69 (1.26, 2.26) |

| >$12,000 | 11.8 | N/A | 354 | 107 | 1.00 (ref) | 1.00 (ref) |

| Health insurance | ||||||

| Yes | 13.8 | 16.5 | 1110 | 204 | 3.71 (2.19, 6.28) | 3.01 (1.85, 4.88) |

| No | 6.9 | 10.0 | 75 | 28 | 1.00 (ref) | 1.00 (ref) |

| Lives in their own place | ||||||

| Yes | 13.5 | 16.5 | 922 | 195 | 0.80 (0.54, 1.18) | |

| No | 14.0 | N/A | 268 | 37 | 1.00 (ref) | |

| Number of years smokeda | ||||||

| <10 | 12.9 | 16.5 | 202 | 53 | 1.00 (ref) | |

| 10–19 | 12.3 | N/A | 438 | 79 | 1.70 (1.12, 2.57) | |

| ≥20 | 13.7 | N/A | 550 | 100 | 1.61 (1.08, 2.39) | |

| Depressive symptoms (CESD) | ||||||

| <23 | 13.0 | N/A | 697 | 142 | 1.00 (ref) | |

| ≥23 | 14.0 | 16.5 | 356 | 55 | 1.03 (0.71, 1.48) | |

| Alcohol use | ||||||

| None | 13.1 | N/A | 684 | 154 | 1.00 (ref) | 1.00 (ref) |

| 1–6 drinks/week | 13.9 | 16.5 | 350 | 67 | 1.30 (0.94, 1.81) | 1.21 (0.90, 1.64) |

| >6 drinks/week or >3 in 1 sitting | 7.4 | N/A | 124 | 9 | 2.73 (1.45, 5.17) | 2.17 (1.18, 3.99) |

| Marijuana use | ||||||

| Yes | 12.7 | N/A | 224 | 31 | 1.54 (1.02, 2.31) | |

| No | 13.4 | 16.5 | 938 | 201 | 1.00 (ref) | |

| Crack/cocaine/heroin use | ||||||

| Yes | 14.0 | N/A | 201 | 13 | 3.32 (1.92, 5.75) | 2.63 (1.59, 4.37) |

| No | 13.3 | 16.5 | 961 | 219 | 1.00 (ref) | 1.00 (ref) |

| Health rating (self-report) | ||||||

| Good to excellent | 13.5 | 16.5 | 530 | 107 | 1.00 (ref) | |

| Fair to poor | 13.0 | N/A | 381 | 44 | 1.73 (1.09, 2.74) | |

| Hospitalized in past 6 months | ||||||

| Yes | 11.9 | N/A | 376 | 50 | 1.39 (0.98, 1.98) | |

| No | 13.4 | 16.5 | 812 | 182 | 1.00 (ref) | |

| Pregnant in past 6 months | ||||||

| Yes | 7.9 | 11.4 | 19 | 9 | 0.26 (0.10, 0.68) | 0.34 (0.15, 0.81) |

| No | 13.5 | 16.5 | 1022 | 199 | 1.00 (ref) | 1.00 (ref) |

| Childcare responsibilities | ||||||

| Yes | 13.4 | 16.5 | 275 | 59 | 0.76 (0.51, 1.12) | |

| No | 13.7 | N/A | 805 | 136 | 1.00 (ref) | |

| Hypertension | ||||||

| Yes | 14.6 | 16.5 | 430 | 63 | 2.07 (1.51, 2.85) | 1.91 (1.40, 2.60) |

| No | 13 | N/A | 762 | 169 | 1.00 (ref) | 1.00 (ref) |

| Diabetes | ||||||

| Yes | 12.2 | N/A | 183 | 51 | 0.78 (0.53, 1.15) | |

| No | 13.8 | 16.5 | 1006 | 181 | 1.00 (ref) | |

| Cervical intraepithelial neoplasia | ||||||

| Yes | 12.1 | N/A | 202 | 25 | 1.36 (0.87, 2.12) | |

| No | 13.5 | 16.5 | 870 | 186 | 1.00 (ref) | |

| HAART use | ||||||

| Yes | 14.4 | N/A | 628 | 103 | 2.86 (2.17, 3.76) | 3.70 (2.76, 4.97) |

| No | 12.4 | 16.5 | 564 | 129 | 1.00 (ref) | 1.00 (ref) |

| CD4 cell count group | ||||||

| <200 | 13.2 | N/A | 369 | 38 | 1.51 (1.00, 2.28) | 1.85 (1.25, 2.74) |

| 200–499 | 11.9 | N/A | 384 | 105 | 0.59 (0.42, 0.84) | 0.78 (0.57, 1.07) |

| ≥500 | 13.8 | 16.5 | 382 | 85 | 1.00 (ref) | 1.00 (ref) |

| HIV viral load group, copies | ||||||

| <4,001 | 13.9 | 16.5 | 652 | 135 | 1.00 (ref) | |

| 4,001–50,000 | 11.9 | N/A | 197 | 50 | 0.46 (0.31, 0.67) | |

| >50,000 | 12.8 | N/A | 276 | 34 | 1.01 (0.68, 1.52) | |

Note: Boldface indicates p<0.005.

Baseline covariates.

CESD, Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression Scale; HAART, highly active antiretroviral therapy; N/A, not applicable

Smoking Recidivism

Of the 316 participants who reported sustained smoking cessation during follow-up, 273 women had at least one subsequent follow-up visit. Of these 273 women, 145 (53%) reported that they began smoking again during study follow-up, with a median time to recidivism of 6.0 years (mean=7.2 years). In adjusted analysis, marijuana use and enrollment in 1994–1996 were associated with shorter time to cigarette smoking recidivism (TR<1, Table 3). In this same analysis, living in one's own place was significantly associated with longer time to recidivism (TR>1, Table 3). In an adjusted analysis among HIV-infected women only, enrollment in 2001–2002 and crack/cocaine/heroin use were associated with a shorter time to recidivism (TR<1, Table 4), whereas older age and HAART use were associated with a longer time to recidivism (TR>1).

Table 3.

Time from smoking cessation to resumption of smoking among sustained quitters

| Kaplan-Meier | Unadjusted log-normal | Adjusted log-normal | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristic | M | Median | n total | n relapse | time ratio (95% CI) | time ratio (95% CI) |

| HIV statusa | ||||||

| infected | 5.3 | 3.0 | 71 | 45 | 1.00 (ref) | |

| HIV-infected | 7.5 | 6.7 | 202 | 100 | 1.31 (0.87, 1.97) | |

| Statea | ||||||

| California | 7.1 | 4.7 | 91 | 51 | 0.87 (0.57, 1.33) | |

| District of Columbia | 3.9 | 4.0 | 26 | 14 | 0.71 (0.37, 1.38) | |

| Illinois | 7.2 | 7.7 | 39 | 21 | 1.00 (0.57, 1.75) | |

| New York | 7 | 6.0 | 117 | 59 | 1.00 (ref) | |

| Age group, yearsa | ||||||

| 18–29 | 4.0 | 2.0 | 56 | 35 | 1.00 (ref) | |

| 30–39 | 7.1 | 6.3 | 123 | 66 | 1.73 (1.14, 2.62) | |

| 40–49 | 7.8 | 8.0 | 79 | 39 | 1.63 (1.05, 2.55) | |

| ≥50 | 4.6 | N/A | 15 | 5 | 2.01 (0.80, 5.07) | |

| Recruitment waveb | ||||||

| 1994–1995 | 7.7 | 6.9 | 206 | 106 | 1.00 (ref) | 1.00 (ref) |

| 2001–2002 | 3.7 | 2 | 67 | 39 | 0.54 (0.36, 0.81) | 0.55 (0.37, 0.82) |

| Race/ethnicitya | ||||||

| African American | 7.2 | 6.9 | 168 | 81 | 1.00 (ref) | |

| Latina | 2.8 | 2 | 20 | 17 | 0.37 (0.19, 0.72) | |

| Other | 8.1 | 7.7 | 46 | 23 | 1.20 (0.73, 1.98) | |

| White | 6.7 | 5.1 | 39 | 24 | 0.84 (0.50, 1.41) | |

| Living with partner | ||||||

| Yes | 5.3 | 3.3 | 74 | 48 | 0.82 (0.55, 1.23) | |

| No | 7.1 | 6.3 | 180 | 94 | 1.00 (ref) | |

| Educational attainment | ||||||

| <High school | 5.0 | 4.0 | 95 | 52 | 0.83 (0.57, 1.21) | |

| ≥High school | 7.2 | 6.0 | 171 | 93 | 1.00 (ref) | |

| Employed | ||||||

| Yes | 7.4 | 6 | 91 | 50 | 1.03 (0.70, 1.52) | |

| No | 6.5 | 4.9 | 175 | 95 | 1.00 (ref) | |

| Yearly household income | ||||||

| ≤$12,000 | 6.6 | 4.9 | 135 | 79 | 0.85 (0.59, 1.23) | |

| >$12,000 | 6.9 | 5.0 | 118 | 62 | 1.00 (ref) | |

| Health insurance | ||||||

| Yes | 7.2 | 6 | 229 | 120 | 1.13 (0.77, 2.20) | |

| No | 6 | 4.0 | 36 | 24 | 1.00 (ref) | |

| Lives in their own place | ||||||

| Yes | 7.3 | 2 | 223 | 112 | 2.23 (1.39, 3.57) | 2.13 (1.35, 3.36) |

| No | 4.3 | 2 | 43 | 33 | 1.00 (ref) | 1.00 (ref) |

| Number of years smoked a | ||||||

| <10 | 6.8 | 3.0 | 82 | 47 | 1.00 (ref) | |

| 10–19 | 7.0 | 6.9 | 87 | 46 | 1.15 (0.72, 1.82) | |

| ≥20 | 7.1 | 6.3 | 104 | 52 | 1.30 (0.83, 2.03) | |

| Depressive symptoms (CESD) | ||||||

| <23 | 7.6 | 8 | 184 | 88 | 1.00 (ref) | |

| ≥23 | 5.1 | 4 | 54 | 36 | 0.57 (0.35, 0.92) | |

| Alcohol use | ||||||

| None | 7.5 | 7 | 131 | 61 | 1.00 (ref) | |

| 1–6 drinks/week | 6.3 | 6 | 57 | 33 | 0.73 (0.46, 1.17) | |

| >6 drinks/week or >3 in 1 sitting | 5.7 | 4 | 8 | 6 | 0.88 (0.34, 2.26) | |

| Marijuana use | ||||||

| Yes | 4.6 | 2 | 36 | 28 | 0.52 (0.31, 0.87) | 0.57 (0.35, 0.92) |

| No | 7.2 | 6.7 | 230 | 117 | 1.00 (ref) | 1.00 (ref) |

| Crack/cocaine/heroin use | ||||||

| Yes | 4.2 | 3 | 24 | 23 | 0.51 (0.28, 0.92) | |

| No | 7.2 | 6.3 | 242 | 122 | 1.00 (ref) | |

| Health rating (self-report) | ||||||

| Good to excellent | 7.5 | 8 | 139 | 69 | 1.00 (ref) | |

| Fair to poor | 8.1 | 6.3 | 58 | 23 | 1.06 (0.61, 1.85) | |

| Hospitalized in past 6 months | ||||||

| Yes | 7 | 6.3 | 65 | 30 | 1.03 (0.66, 1.62) | |

| No | 7.1 | 5.1 | 207 | 115 | 1.00 (ref) | |

| Childcare responsibilities | ||||||

| Yes | 6.5 | 7.7 | 75 | 33 | 1.20 (0.76, 1.90) | |

| No | 7.3 | 6.3 | 162 | 86 | 1.00 (ref) | |

| Hypertension | ||||||

| Yes | 8.2 | 10.6 | 105 | 49 | 1.47 (1.00, 2.14) | |

| No | 6.3 | 4 | 167 | 96 | 1.00 (ref) | |

| Diabetes | ||||||

| Yes | 6.5 | 4 | 62 | 38 | 0.88 (0.57, 1.34) | |

| No | 7.4 | 6.9 | 211 | 107 | 1.00 (ref) | |

| Cervical intraepithelial neoplasia | ||||||

| Yes | 3.3 | 2.1 | 23 | 15 | 0.73 (0.40, 1.36) | |

| No | 6.8 | 4.8 | 216 | 92 | 1.00 (ref) | |

Note: Boldface indicates p<0.05. Owing to smaller sample size, pregnancy history is not included.

Baseline covariates.

Follow-up for recidivism was not long enough for women in wave 3 to be included in these analyses.

CESD, Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression Scale; N/A, not applicable.

Table 4.

Time from smoking cessation to resumption of smoking among HIV-infected sustained quitters

| Kaplan-Meier | Unadjusted log-normal | Adjusted log-normal | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristic | M | Median | n total | n relapse | time ratio (95% CI) | time ratio (95% CI) |

| Statea | ||||||

| California | 6.9 | 4.7 | 57 | 32 | 0.73 (0.43, 1.22) | |

| District of Columbia | 3.7 | 2.0 | 22 | 12 | 0.53 (0.26, 1.10) | |

| Illinois | 7.4 | 7.7 | 36 | 19 | 0.90 (0.49, 1.65) | |

| New York | 7.8 | 7.0 | 87 | 37 | 1.00 (ref) | |

| Age group (years)a | ||||||

| 18–29 | 4.4 | 2.0 | 28 | 15 | 1.00 (ref) | 1.00 (ref) |

| 30–39 | 6.8 | 6.0 | 98 | 54 | 1.58 (0.92, 2.71) | 1.50 (0.90, 2.49) |

| 40–49 | 8.3 | 10.6 | 65 | 29 | 1.85 (1.05, 3.26) | 1.88 (1.09, 3.27) |

| ≥50 | 2.3 | N/A | 11 | 2 | 3.23 (0.89, 11.77) | 2.08 (0.65, 6.67) |

| Recruitment waveb | ||||||

| 1994–1995 | 7.8 | 7.0 | 163 | 80 | 1.00 (ref) | 1.00 (ref) |

| 2001–2002 | 2.2 | 3.0 | 39 | 20 | 0.57 (0.34, 0.97) | 0.57 (0.34, 0.94) |

| Race/ethnicitya | ||||||

| African American | 7.5 | 6.9 | 132 | 59 | 1.00 (ref) | |

| Latina | 2.0 | 2.0 | 10 | 8 | 0.38 (0.15, 0.93) | |

| Other | 8.6 | 7.7 | 31 | 14 | 1.26 (0.69, 2.33) | |

| White | 6.4 | 4.9 | 29 | 19 | 0.74 (0.41, 1.35) | |

| Living with partner | ||||||

| Yes | 5.9 | 6.0 | 53 | 31 | 1.04 (0.65, 1.67) | |

| No | 7.1 | 6.3 | 136 | 68 | 1.00 (ref) | |

| Educational attainment | ||||||

| <High school | 5.3 | 6.7 | 67 | 34 | 0.90 (0.57, 1.42) | |

| ≥High school | 7.4 | 6.3 | 129 | 66 | 1.00 (ref) | |

| Employed | ||||||

| Yes | 7.1 | 3.0 | 57 | 33 | 0.76 (0.48, 1.21) | |

| No | 7.1 | 6.3 | 139 | 67 | 1.00 (ref) | |

| Yearly household income | ||||||

| ≤$12,000 | 7.0 | 6.0 | 103 | 56 | 0.83 (0.49, 1.41) | |

| >$12,000 | 6.4 | 7.7 | 42 | 21 | 1.00 (ref) | |

| Health insurance | ||||||

| Yes | 7.4 | 6.3 | 177 | 87 | 1.23 (0.60, 2.53) | |

| No | 6.4 | 5.4 | 18 | 12 | 1.00 (ref) | |

| Lives in their own place | ||||||

| Yes | 7.4 | 6.9 | 168 | 81 | 1.79 (0.98, 3.24) | |

| No | 5.2 | 2.0 | 28 | 19 | 1.00 (ref) | |

| Number of years smokeda | ||||||

| <10 | 6.7 | 3.0 | 47 | 26 | 1.00 (ref) | |

| 10–19 | 7.2 | 7.0 | 68 | 35 | 1.19 (0.67, 2.10) | |

| ≥20 | 7.6 | 7.7 | 87 | 39 | 1.38 (0.80, 2.39) | |

| Depressive symptoms (CESD) | ||||||

| <23 | 7.7 | 8.7 | 135 | 61 | 1.00 (ref) | |

| ≥23 | 5.5 | 4.0 | 41 | 25 | 0.63 (0.35, 1.11) | |

| Alcohol use | ||||||

| None | 7.5 | 7 | 131 | 61 | 1.00 (ref) | |

| 1–6 drinks/week | 6.3 | 6 | 57 | 33 | 0.73 (0.46, 1.17) | |

| >6 drinks/week or >3 in 1 sitting | 5.7 | 4 | 8 | 6 | 0.88 (0.34, 2.26) | |

| Marijuana use | ||||||

| Yes | 4.7 | 2.5 | 24 | 18 | 0.53 (0.29, 0.99) | |

| No | 7.4 | 7.0 | 172 | 82 | 1.00 (ref) | |

| Crack/cocaine/heroin use | ||||||

| Yes | 4.2 | 3.0 | 20 | 19 | 0.49 (0.25, 0.94) | 0.49 (0.26, 0.93) |

| No | 7.5 | 7.7 | 176 | 81 | 1.00 (ref) | 1.00 (ref) |

| Health rating (self-report) | ||||||

| Good to excellent | 7.5 | 7.7 | 102 | 50 | 1.00 (ref) | |

| Fair to poor | 8.3 | 6.9 | 49 | 18 | 1.16 (0.63, 2.16) | |

| Hospitalized in past 6 months | ||||||

| Yes | 6.9 | 6.3 | 58 | 26 | 1.00 (0.61, 1.65) | |

| No | 7.5 | 6.7 | 143 | 74 | 1.00 (ref) | |

| Childcare responsibilities | ||||||

| Yes | 6.3 | 7.7 | 55 | 24 | 1.00 (0.59, 1.71) | |

| No | 7.8 | 6.7 | 121 | 58 | 1.00 (ref) | |

| Hypertension | ||||||

| Yes | 8.4 | 10.6 | 83 | 37 | 1.35 (0.87, 2.10) | |

| No | 6.6 | 6.0 | 118 | 63 | 1.00 (ref) | |

| Diabetes | ||||||

| Yes | 6.8 | 4.7 | 47 | 27 | 0.90 (0.55, 1.48) | |

| No | 7.6 | 7.7 | 155 | 73 | 1.00 (ref) | |

| Cervical intraepithelial neoplasia | ||||||

| Yes | 3.2 | 2.1 | 21 | 14 | 0.60 (0.31, 1.16) | |

| No | 7.4 | 6.3 | 155 | 80 | 1.00 (ref) | |

| HAART use | ||||||

| Yes | 8.4 | 10.6 | 125 | 51 | 2.37 (1.55, 3.62) | 2.21 (1.46, 3.36) |

| No | 4.9 | 3.0 | 76 | 49 | 1.00 (ref) | 1.00 (ref) |

| CD4 cell count group | ||||||

| <200 | 4.6 | 5.1 | 39 | 21 | 0.74 (0.40, 1.37) | |

| 200–499 | 6.7 | 4.8 | 82 | 47 | 0.76 (0.46, 1.25) | |

| ≥500 | 8.5 | 14.1 | 69 | 30 | 1.00 (ref) | |

| HIV viral load group | ||||||

| <4,001 | 8.2 | 9.0 | 135 | 64 | 1.00 (ref) | |

| 4,001–50,000 | 4.1 | 3.3 | 36 | 26 | 0.49 (0.29, 0.84) | |

| >50,000 | 3.9 | 4.4 | 16 | 7 | 0.72 (0.30, 1.71) | |

Note: Boldface indicates p<0.05. Owing to smaller sample size, pregnancy history is not included.

Baseline covariates.

Follow-up for recidivism was not long enough for women in wave 3 to be included in these analyses.

CESD, Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression Scale; HAART, highly active antiretroviral therapy; N/A, not applicable

Discussion

One unique finding of our study was that HIV-infected women with CD4+ cell counts <200 had a longer time to smoking cessation than those with counts ≥500. This may be because women with more severe immune deficiency are less motivated to quit smoking than women with higher CD4+ cell counts, and is in keeping with our finding that women who rated their overall health as poor or fair had a longer time to smoking cessation than women who rated their health as good or excellent. Interventions that increase the motivation to quit smoking can stimulate quit attempts and make them more successful.27–29 In addition, HIV-infected women using HAART also had a longer time to quit but had a longer time to recidivism than women not taking HAART. Because HAART use may be confounded by its indications, such as having AIDS-related comorbidities and immunosuppression, that may explain the longer time to cessation among HAART users. On the other hand, the longer time to recidivism may reflect a greater motivation for health improvement among HIV-infected women who are adherent to effective ART and have more access to professional healthcare advice and assistance regarding smoking cessation. Raising the awareness of the health benefits of quitting smoking and sustaining cessation and offering alternative coping strategies, including medications to alleviate withdrawal symptoms,30 are important first steps toward cessation. HIV-infected individuals, especially those with CD4+ cell counts <200 and those prescribed HAART, are likely to have frequent encounters with healthcare professionals, and these providers should take the opportunity to promote smoking cessation among their patients who smoke. Clinicians treating HIV-infected smokers with comorbid medical conditions have an ideal opportunity to teach the patients that they are treating that their health conditions may be exacerbated by smoking and can be ameliorated by quitting.27,31–33 One framework for integrating strategies for smoking cessation in the healthcare setting is based on the principles of asking, assessing, advising, assisting and arranging—the five A's.34 This framework complements the motivational approach and has been successfully applied in practice to guide patients through and beyond their quit attempt.35

Several of the factors associated with longer time to smoking cessation and shorter time to recidivism among HIV-infected and at-risk women in this study were similar to those reported in other studies, such as lower educational attainment and income, higher number of years smoked, alcohol and drug use, and not living in one's own place.13,36–39 Our study identified factors that may inform the design of programs and interventions to lower smoking rates in HIV-infected and at-risk women. Specifically, interventions that target smoking cessation as soon as possible after initiation, integrate risk reduction for multiple addictions and high-risk behaviors simultaneously, teach coping skills for high-stress situations, and address structural factors such as housing instability and unemployment may be more effective in helping women achieve and sustain smoking cessation.38,40

Among the health conditions included in our analytic models, being pregnant in the past 6 months was associated with a shorter time to sustained cessation. It has been established that pregnant women are more likely to quit smoking21,22 and our study provided further evidence to support those findings. We also found that women with hypertension had a longer time to sustained smoking cessation than women without hypertension. Although cigarette smoking may increase the risk of hypertension,41,42 we found that hypertension delayed cessation. This suggests that motivating women to quit smoking during pregnancy may be a teachable moment that could be used in other health-related situations such as motivating women with hypertension to quit smoking.

Unexpectedly, women with any type of health insurance had a longer time to cessation than women without insurance. This may be because women without health insurance are more concerned about avoiding behaviors that may increase their risk of ill health. One study that evaluated smoking cessation in subgroups of the insured and uninsured found those with insurance were more likely to use “dependence treatments” for cessation but that the prevalence of quit attempts was similar between the insured and uninsured,43 implying similar motivation to quit in both groups.

The strengths of this study include a large, geographically and ethnically diverse, representative sample of U.S. women with and at risk for HIV. By incorporating the most recent participant data, these longitudinal analyses allowed us to determine the most proximal factors associated with quitting and recidivism. However, this study had several limitations. First, we relied on self-reported cessation and recidivism and did not test for biomarkers of tobacco use. However, our participants had little reason to be untruthful in their responses to the tobacco questions. Second, this cohort is dynamic with individuals entering (three enrollment phases) and leaving (owing to death and loss to study follow-up) during the study period. Therefore, changes in the study population over time may also have contributed to the temporal trends we observed. Third, this study was not guided by conceptual or theoretical frameworks. Instead, we sought to generate hypotheses about the types of interventions that might be targeted for women with and at risk for HIV infection.

The WIHS is an observational cohort study, and although this investigation did not include new policy or counseling interventions, our data suggest that new public health policies and programs tailored to raise awareness and motivate this population of HIV-infected and at-risk women to quit smoking are needed. This is particularly important given the recent finding that HIV-infected smokers lose more years of life to smoking than to HIV infection10 and because the current smoking rate of 39% among WIHS participants is more than double the national average of 17% for women.44 Our results suggest a shift away from the dominant, single-behavior paradigm of treating each health risk behavior as if it were isolated, to a multiple-behavior paradigm that applies innovative integrative models and techniques to impact multiple behaviors.45 Programs that treat smoking as well as drug and alcohol addiction and policies that discourage cigarette smoking can further reduce cigarette consumption among these women. Interventions that specifically target recent initiators of cigarette smoking and address perceptions of health and health outcomes, housing needs, and income may have greater success in achieving sustained cessation. Evidence–based smoking cessation approaches for women with and at risk for HIV infection should be individualized and provide continued support to address the syndemic of high levels of stress, drug and alcohol dependency, and comorbidities.46 Integrating smoking-cessation interventions into ongoing HIV/AIDS programs, educating HIV-infected persons about the harms of smoking, and teaching coping skills that can help individuals deal with life's challenges without relapsing to smoking may further reduce morbidity and mortality in women and men with HIV infection.

Acknowledgments

Data in this manuscript were collected by the Women's Interagency HIV Study (WIHS) Collaborative Study Group with centers (principal investigators) at New York City/Bronx Consortium (Kathryn Anastos); Brooklyn New York (Howard Minkoff); Washington DC Metropolitan Consortium (Mary Young); The Connie Wofsy Study Consortium of Northern California (Ruth Greenblatt); Los Angeles County/Southern California Consortium (Alexandra Levine); Chicago Consortium (Mardge Cohen); Data Coordinating Center (Stephen Gange). The WIHS is funded by the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (UO1-AI-35004, UO1-AI-31834, UO1-AI-34994, UO1-AI-34989, UO1-AI-34993, and UO1-AI-42590) and by the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (UO1-HD-32632). The study is co-funded by the National Cancer Institute, the National Institute on Drug Abuse, and the National Institute on Deafness and Other Communication Disorders. Funding is also provided by the National Center for Research Resources (UCSF-CTSI Grant Number UL1 RR024131). K. Weber is also supported by P30 AI 082151. The contents of this publication are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of the NIH.

Footnotes

No financial disclosures were reported by the authors of this paper.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Contributor Information

Nancy A. Hessol, Department of Clinical Pharmacy, University of California, San Francisco.

Kathleen M. Weber, CORE Center, Cook County Health and Hospital System and Rush University, Chicago, Illinois.

Gypsyamber D'Souza, Department of Epidemiology, Bloomberg School of Public Health, Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, Maryland.

Dee Burton, Department of Community Health Sciences, School of Public Health, State University of New York Downstate Medical Center, Brooklyn.

Mary Young, Georgetown University School of Medicine, Washington, District of Columbia.

Joel Milam, Department of Preventive Medicine, Keck School of Medicine, University of Southern California, Los Angeles, California.

Lynn Murchison, Division of Internal Medicine, Montefiore Medical Center, Bronx, New York.

Monica Gandhi, Department of Medicine, University of California, San Francisco.

Mardge H. Cohen, Department of Medicine, Cook County Health and Hospital System and Rush University, Chicago, Illinois.

References

- 1.Cigarette smoking-attributable morbidity--U.S., 2000. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2003;52(35):842–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.The 2004 U.S. Surgeon General's report: the health consequences of smoking. N S W Public Health Bull. 2004;15(5–6):107. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Smoking-attributable mortality, years of potential life lost, and productivity losses--U.S.,2000–2004. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2008;57(45):1226–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.The Surgeon General's 1990 report on the health benefits of smoking cessation. Executive summary. MMWR Recomm Rep. 1990;39(RR-12):i–xv. 1–12. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jha P, Ramasundarahettige C, Landsman V, et al. 21st-century hazards of smoking and benefits of cessation in the U.S. N Engl J Med. 2013;368(4):341–50. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa1211128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pirie K, Peto R, Reeves GK, Green J, Beral V. The 21st century hazards of smoking and benefits of stopping: a prospective study of one million women in the UK. Lancet. 2013;381(9861):133–141. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)61720-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Crothers K, Griffith TA, McGinnis KA, et al. The impact of cigarette smoking on mortality, quality of life, and comorbid illness among HIV-positive veterans. J Gen Intern Med. 2005;20(12):1142–5. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2005.0255.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Crothers K, Goulet JL, Rodriguez-Barradas MC, et al. Impact of cigarette smoking on mortality in HIV-positive and HIV-negative veterans. AIDS Educ Prev. 2009;21(3S):S40–S53. doi: 10.1521/aeap.2009.21.3_supp.40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lifson AR, Neuhaus J, Arribas JR, van den Berg-Wolf M, Labriola AM, Read TR. Smoking-related health risks among persons with HIV in the Strategies for Management of Antiretroviral Therapy clinical trial. Am J Public Health. 2010;100(10):1896–1903. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2009.188664. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Helleberg M, Afzal S, Kronborg G, et al. Mortality attributable to smoking among HIV-1-infected individuals: a nationwide, population-based cohort study. Clin Infect Dis. 2013;56(5):727–34. doi: 10.1093/cid/cis933. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Scheer S, Hessol NA. Epidemiology of cancer in the pre-HAART And HAART eras. In: Volberding P, Palefsky J, editors. Viral and immunologic, malignancies. Hamilton ON: BC Dekker, Inc; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Petoumenos K, Worm S, Reiss P, et al. Rates of cardiovascular disease following smoking cessation in patients with HIV infection: results from the D:A:D study(*) HIV Med. 2011;12(7):412–21. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-1293.2010.00901.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Huber M, Ledergerber B, Sauter R, et al. Outcome of smoking cessation counselling of HIV-positive persons by HIV care physicians. HIV Med. 2012;13(7):387–97. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-1293.2011.00984.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Levine AM, Seaberg EC, Hessol NA, et al. HIV as a risk factor for lung cancer in women: data from the Women's Interagency HIV Study. J Clin Oncol. 2010 Mar 20;28(9):1514–1519. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.25.6149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Goldberg D, Weber KM, Orsi J, et al. Smoking Cessation Among Women with and at Risk for HIV: Are They Quitting? J Gen Intern Med. 2009 Nov 17; doi: 10.1007/s11606-009-1150-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Barkan SE, Melnick SL, Preston-Martin S, et al. The Women's Interagency HIV Study. WIHS Collaborative Study Group. Epidemiology. 1998;9(2):117–25. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bacon MC, von Wyl V, Alden C, et al. The Women's Interagency HIV Study: an observational cohort brings clinical sciences to the bench. Clin Diagn Lab Immunol. 2005;12(9):1013–9. doi: 10.1128/CDLI.12.9.1013-1019.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hessol NA, Schneider M, Greenblatt RM, et al. Retention of women enrolled in a prospective study of human immunodeficiency virus infection: impact of race, unstable housing, and use of human immunodeficiency virus therapy. Am J Epidemiol. 2001;154(6):563–73. doi: 10.1093/aje/154.6.563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hessol NA, Weber KM, Holman S, et al. Retention and attendance of women enrolled in a large prospective study of HIV-1 in the U.S. J Womens Health (Larchmt) 2009;18(10):1627–37. doi: 10.1089/jwh.2008.1337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Moadel AB, Bernstein SL, Mermelstein RJ, Arnsten JH, Dolce EH, Shuter J. A randomized controlled trial of a tailored group smoking cessation intervention for HIV-infected smokers. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2012;61(2):208–15. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e3182645679. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.A report of the Surgeon General. Rockville MD: USDHHS; 2001. Women and smoking. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Graham H, Hawkins SS, Law C. Lifecourse influences on women's smoking before, during and after pregnancy. Soc Sci Med. 2010;70(4):582–7. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2009.10.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cook JA, Cohen MH, Burke J, et al. Effects of depressive symptoms and mental health quality of life on use of highly active antiretroviral therapy among HIV-seropositive women. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2002;30(4):401–9. doi: 10.1097/00042560-200208010-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cook JA, Grey D, Burke J, et al. Depressive symptoms and AIDS-related mortality among a multisite cohort of HIV-positive women. Am J Public Health. 2004;94(7):1133–40. doi: 10.2105/ajph.94.7.1133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wu AW, Rubin HR, Mathews WC, et al. A health status questionnaire using 30 items from the Medical Outcomes Study. Preliminary validation in persons with early HIV infection. Med Care. 1991;29(8):786–98. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199108000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hosmer DW, Jr, Lemeshow S. Applied survival analysis: regression modeling for time to event data. New York: John Wiley and Sons; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Fiore MC, Jaen CR, Baker TB, Bailey WC, Benowitz NL, Curry SJ. Treating tobacco use and dependence: 2008 update. Rockville MD: USDHHS; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Williams GC, McGregor HA, Sharp D, et al. Testing a self-determination theory intervention for motivating tobacco cessation: supporting autonomy and competence in a clinical trial. Health Psychol. 2006;25(1):91–101. doi: 10.1037/0278-6133.25.1.91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Baker TB, Mermelstein R, Collins LM, et al. New methods for tobacco dependence treatment research. Ann Behav Med. 2011;41(2):192–207. doi: 10.1007/s12160-010-9252-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Stead LF, Lancaster T. Interventions to reduce harm from continued tobacco use. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2007;(3):CD005231. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD005231.pub2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ebbert JO, Sood A, Hays JT, Dale LC, Hurt RD. Treating tobacco dependence: review of the best and latest treatment options. J Thorac Oncol. 2007;2(3):249–256. doi: 10.1097/JTO.0b013e318031bca4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Taylor KL, Cox LS, Zincke N, Mehta L, McGuire C, Gelmann E. Lung cancer screening as a teachable moment for smoking cessation. Lung Cancer. 2007;56(1):125–34. doi: 10.1016/j.lungcan.2006.11.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.McBride CM, Emmons KM, Lipkus IM. Understanding the potential of teachable moments: the case of smoking cessation. Health Educ Res. 2003;18(2):156–70. doi: 10.1093/her/18.2.156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Fiore MC, Baker TB. Clinical practice. Treating smokers in the health care setting. N Engl J Med. 2011;365(13):1222–31. doi: 10.1056/NEJMcp1101512. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Fiore MC, Bailey WC, Cohen SJ, et al. A clinical practice guideline for treating tobacco use and dependence - A U.S. Public Health Service report. JAMA. 2000;283(24):3244–54. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hymowitz N, Cummings KM, Hyland A, Lynn WR, Pechacek TF, Hartwell TD. Predictors of smoking cessation in a cohort of adult smokers followed for five years. Tob Control. 1997;6(2S):S57–S62. doi: 10.1136/tc.6.suppl_2.s57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Shah NG, Galai N, Celentano DD, Vlahov D, Strathdee SA. Longitudinal predictors of injection cessation and subsequent relapse among a cohort of injection drug users in Baltimore MD, 1988–2000. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2006;83(2):147–56. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2005.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Shankar A, McMunn A, Steptoe A. Health-related behaviors in older adults relationships with socioeconomic status. Am J Prev Med. 2010;38(1):39–46. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2009.08.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.van Reek J, Adriaanse H. Cigarette smoking cessation rates by level of education in five western countries. Int J Epidemiol. 1988;17(2):474–5. doi: 10.1093/ije/17.2.474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hall SM, Prochaska JJ. Treatment of smokers with co-occurring disorders: emphasis on integration in mental health and addiction treatment settings. Annu Rev Clin Psychol. 2009;5:409–31. doi: 10.1146/annurev.clinpsy.032408.153614. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kim JW, Park CG, Hong SJ, et al. Acute and chronic effects of cigarette smoking on arterial stiffness. Blood Press. 2005;14(2):80–5. doi: 10.1080/08037050510008896. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Leone A. Relationship between cigarette smoking and other coronary risk factors in atherosclerosis: risk of cardiovascular disease and preventive measures. Curr Pharm Des. 2003;9(29):2417–23. doi: 10.2174/1381612033453802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Bandi P, Cokkinides VE, Virgo KS, Ward EM. The receipt and utilization of effective clinical smoking cessation services in subgroups of the insured and uninsured populations in the U.S. J Behav Health Serv Res. 2012;39(2):202–13. doi: 10.1007/s11414-011-9255-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Vital signs: current cigarette smoking among adults aged ≥18 years--U.S., 2005–2010. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2011;60(35):1207–12. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Redding CA. Towards integrated multiple behavior management for HIV and chronic conditions: a comment on Blashill et al. Ann Behav Med. 2013;46(2):131–2. doi: 10.1007/s12160-013-9506-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Lifson AR, Lando HA. Smoking and HIV: prevalence, health risks, and cessation strategies. Curr HIV/AIDS Rep. 2012;9(3):223–30. doi: 10.1007/s11904-012-0121-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]