Abstract

Purpose

To elucidate key elements surrounding acceptability/feasibility, language, and structure of a text message-based preventive intervention for high-risk adolescent females.

Methods

We recruited high-risk 13- to 17-year-old females screening positive for past-year peer violence and depressive symptoms, during emergency department visits for any chief complaint. Participants completed semistructured interviews exploring preferences around text message preventive interventions. Interviews were conducted by trained interviewers, audio-recorded, and transcribed verbatim. A coding structure was iteratively developed using thematic and content analysis. Each transcript was double coded. NVivo 10 was used to facilitate analysis.

Results

Saturation was reached after 20 interviews (mean age 15.4; 55% white; 40% Hispanic; 85% with cell phone access). (1) Acceptability/feasibility themes: A text-message intervention was felt to support and enhance existing coping strategies. Participants had a few concerns about privacy and cost. Peer endorsement may increase uptake. (2) Language themes: Messages should be simple and positive. Tone should be conversational but not slang filled. (3) Structural themes: Messages may be automated but must be individually tailored on a daily basis. Both predetermined (automatic) and as-needed messages are requested. Dose and timing of content should be varied according to participants’ needs. Multimedia may be helpful but is not necessary.

Conclusions

High-risk adolescent females seeking emergency department care are enthusiastic about a text message-based preventive intervention. Incorporating thematic results on language and structure can inform development of future text messaging interventions for adolescent girls. Concerns about cost and privacy may be able to be addressed through the process of recruitment and introduction to the intervention.

Keywords: Adolescents, Health promotion, Text messaging, Behavior change

Mobile health, or “mHealth,” defined by the National Institutes for Health as “the use of mobile and wireless devices to improve health outcomes, healthcare services and health research,” can consist of text messaging, phone-based applications, medical devices, or telemedicine [1]. Using mHealth to deliver preventive interventions may circumvent some limitations of traditional, face-to-face intervention formats [2]. For instance, mHealth can be delivered at the time and place of the participant's choosing; it does not rely on local availability of professionals; and it can be easily upscaled [3,4]. For high-risk populations, who have high rates of mobile phone ownership but low accessibility to traditional health care, mHealth may be a particularly promising format for delivering preventive care [5].

The emergency department (ED) is potentially an important location to implement mHealth behavioral interventions, particularly for adolescents and young adults. The ED is the primary source of care for many teens with high-risk behaviors, including peer violence [6], and provides an important opportunity to initiate preventive interventions [7]. There are numerous limitations to providing such interventions in real time, including lack of time and resources on the part of ED staff, poor accessibility, and availability of community resources and low rates of follow-through with treatment referrals [8,9]. The vast majority of teens presenting to the ED, however, use mobile phones [10,11], and more than 95% of teen ED patients using mobile phones report that they use text messaging [11,12]. Text message-based behavioral interventions have been shown to be acceptable, valid, and reliable with adolescents for a variety of sensitive topics [4,13].

Two ED-based feasibility studies of text message-based behavioral interventions among adults demonstrate that texting may be useful in monitoring risky behaviors in high-risk populations [14,15]. However, both studies had high rates of nonresponse to text messages. For a novel mHealth intervention to be effective, it must have a strong theoretical underpinning in both its content and delivery mechanism [16]. Behavioral theory and related in-depth formative development work have determined the success of most traditional behavioral interventions [17]. To our knowledge, no text message-based studies have been conducted to date with adolescents in the ED, who are potentially more receptive to such a modality than adults [18,19], and no formative research has been conducted exploring ED patients’ preferences for and concerns about a text message-based intervention's content, structure, and tone.

We conducted a formative qualitative study exploring necessary elements of a text message-based preventive intervention for a high-risk population of ED patients: adolescent females with a past year history of peer violence. The study focused exclusively on females because of the unique circumstances surrounding female peer violence [20], the relative lack of interventions for this gender [21], and the higher frequency of texting in this gender [18]. The study's goal was to use patients’ own feedback to optimize acceptability, language, and structure of a text message-based intervention, using the techniques of thematic and content analysis.

Methods

Study design, setting, and population

Participants were recruited for this qualitative intervention development study from the pediatric ED of an urban academic hospital in the Northeast, which serves over 50,000 pediatric patients per year. The patient population is diverse, with 40% publicly insured, 40% Hispanic, and 50% white. During a convenience sample of shifts from July 2012 to April 2013, patients presenting to the ED for any chief complaint were screened for participation using a brief confidential iPad survey. Screening inclusion criteria were 13- to 17-year-old female, English speaking, and parent present. Exclusion criteria for screening were acute suicidality, psychotic symptoms, sexual assault, or child abuse; in police custody; medically unstable; unable to comprehend the consent/assent process; or previously completed the study.

Patients were eligible for interviews if they reported past year peer violence (a modified Conflict Tactics Scale (CTS)-2 score ≥1 [22], representing at least one episode of peer violence victimization or perpetration in the past year) [23], and depressive symptoms (a Patient Health Questionnaire-2 [PHQ-2] score ≥3, the threshold for “moderate depressive symptoms” in adolescents) [24]. We used a modified version of CTS-2 to reflect peer rather than partner violence, per other studies of youth peer violence; questions asked about both victimization and perpetration from peer, nondating partners over the past 12 months (e.g., “I pushed, shoved, or slapped someone” and “Someone pushed, shoved, or slapped me”) [23,25]. The PHQ-2 uses the first two questions of the PHQ-9: “Over the past two weeks how often have you been bothered by any of the following problems: (1) little interest or pleasure in doing things and (2) feeling down, depressed, or hopeless” [24] and has been well validated in adolescents [26,27].

If eligible, participants and their parents were asked to complete an assent/consent process. Interviews were conducted at a time and place of the participant's choice. Participants were compensated $20 for the interview and up to $10 for travel to an interview site. Institutional Review Board approval for the study and a Certificate of Confidentiality from the National Institute of Mental Health were obtained.

Interview protocol

Each one-on-one interview was conducted using a semistructured interview guide. Interviews were facilitated by either the principal investigator or a research assistant, both of whom were trained in qualitative interview facilitation. The interviews lasted approximately 60–90 minutes. The majority of interviews (n = 16) were conducted face to face in a private research of office; the remainder of the interviews was conducted via telephone (n = 3) or in a private room in the library (n = 1). No parents were present for interviews. All interviews were audio recorded and transcribed verbatim.

Semistructured interview guide

The overarching goal of the interviews was to provide formative data regarding high-risk adolescents’ current coping strategies and key elements of a text message-based preventive intervention. The interview guide was developed by emergency physicians with expertise in technology-based ED preventive interventions (M.L.R., R.C., M.J.M., and E.K.C.), a child and adolescent psychologist (A.S.), and a psychologist with expertise in behavioral health and qualitative methodology (K.M.). In order to elicit accurate information about potentially sensitive topics, the interviews began with an “ice breaker” section, regarding participants’ general text messaging habits. It then explored participants’ experiences and means of coping with violence. Next, a potential intervention was described to participants. Interviewers asked participants both for their general impressions of, and specific feedback regarding, intervention structure (e.g., schedule, number of messages, etc.) and possible concerns about the intervention, such as privacy and participant burden. Finally, participants were shown potential text-message intervention content; discussions of potential intervention content are not included in this analysis.

Data analysis

Using thematic analysis [28], an initial coding scheme was developed from the core interview topics (e.g., concerns about privacy, preferences for frequency of messages, and preferred degree of interactivity). Investigators (M.L.R., E.K.C., M.T., and K.M.) reviewed two transcripts then met to develop the coding structure further based on the data collected. The coding structure was iteratively refined after each interview, until the team identified no further themes within the scope of the project goals. An audit trail was kept to track coding decisions and other aspects of analysis throughout the process. Once the coding structure was fully defined, each transcript was coded by at least two investigators independently; the coders then discussed each transcript to ensure comprehensiveness of coding. This process ensured credibility (the qualitative equivalent of “validity”) and transferability and dependability (the qualitative equivalent of “reliability”) of the analysis [29,30]. Thematic saturation of the data was reached at 20 interviews.

The agreed-upon codes were then entered into a qualitative computer software program, NVivo, version 10 (QSR International Pty Ltd., Doncaster, Victoria, Australia), which helps to organize and link codes within electronic interview transcripts. Summaries were written describing the range of data in each code. Finally, the entire research team collectively reviewed the summaries and developed a consensus-based list of major themes.

Results

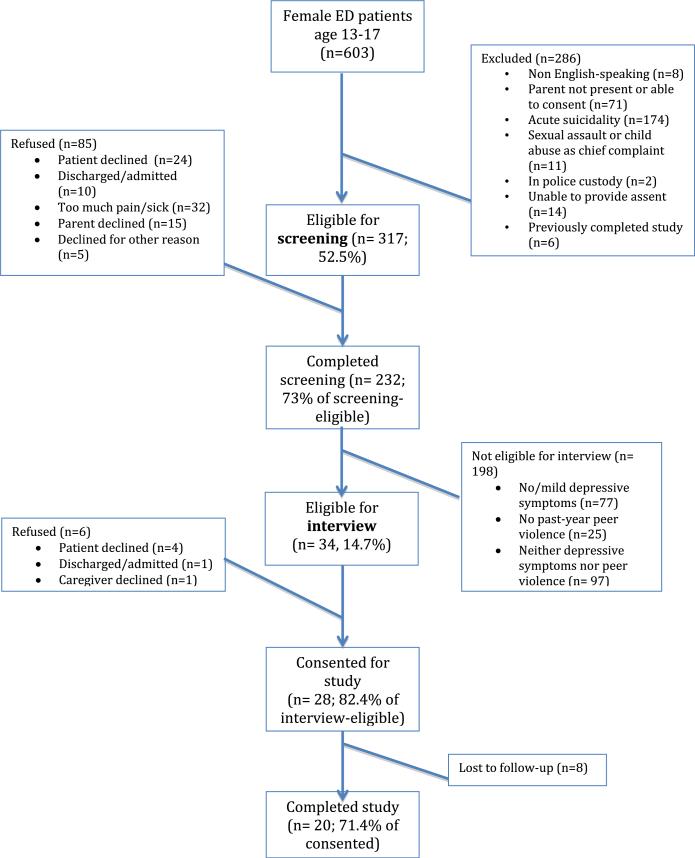

Twenty adolescent female ED patients completed the interviews, representing 71% of those both eligible for and consenting to interviews (Figure 1). Demographics of the participants mirrored the ethnicity and insurance status of our adolescent female ED population (Table 1). Participants reported approximately equal frequency of physical peer victimization (median 4, mean 7 [SD 9.9]) and perpetration (median 4, mean 9.4 [SD 11.9]). Although the majority of participants (85%) reported cell phone access for personal use, only 50% owned smartphones.

Figure 1.

Participant Recruitment Diagram.

Table 1.

Participant demographics (N = 20)

| N (%) | |

|---|---|

| Age (mean [SD]) | 15.4 (1.39) |

| Ethnicity: Hispanic | 8 (40) |

| Race: white | 11 (55) |

| Socioeconomic status: low | 13 (65) |

| Current cellphone access: yes | 17 (85) |

| Lives with either biological parent | 19 (95) |

| Has a source of primary care | 13 (65) |

| PHQ-2 score | |

| Mean (SD) | 4 (.92) |

| Median | 4 |

| CTS score | |

| Mean (SD) | 16.4 (21.2) |

| Median CTS | 10 |

CTS = conflict tactics scale; PHQ = Patient Health Questionnaire; SD = standard deviation.

Themes

Themes are divided according to the three major goals of this analysis: to elucidate (1) acceptability/feasibility; (2) language; and (3) structure of a text message-based preventive intervention for high-risk adolescent females (Table 2).

Table 2.

Illustrative quotes for the major themes

| A: Potential for intervention acceptability/feasibility | |

| A1: High-risk teens are receptive to a proposed violence prevention intervention | It'll help me because I would actually—I actually, like, first of all, like, I'll actually, “All right, somebody's actually asking me how I'm feeling today, and they're gonna, like, help me out.” So it's like—that's helpful, knowing that someone's trying to help you. Yeah. (Participant 9) |

| I feel like sometimes like you just need that little extra reminder. And like you could always look at it throughout the day and like be like okay... That's what I used to do, I used to like save the good ones (text messages from friends) and just read them later. (Participant 18) | |

| I don't really like to talk about my issues, like, through text and stuff like that, but, um, I don't know. I'm sure a lot of other girls would. It's just, I don't think it's for me. (Participant 13) | |

| A2: There were no concerns about stigma and time, but participants did articulate a few concerns about privacy and cost | I have like 500 texts coming to me a day and I had to delete my inbox all the time so three texts isn't gonna be anything. (Participant 6) |

| I think you should also, when introduce yourself, let them know that it's completely like anonymous... and confidential. Like nothing will be shared. (Participant 11) | |

| Well if I didn't have to worry about paying for it, I will do it mainly every day. (Participant 14) | |

| A3: Having an intervention recommended to them by others would increase program uptake | Cuz like if a doctor recommended it, like you'd probably like listen to him more cuz he is like a doctor. (Participant 16) |

| I think it depends on the person. Like if a doctor told it to me like the ways you guys are... And so I was interested in it when the doctor told me, because I was like, “In the moment, I could use that help.” So I think it just depends on like the person and the time of like when it's being told. (Participant 19) | |

| You guys already have teenagers—tell them to put the word out; (other teenagers) probably would listen more cuz they are teenagers themselves... (Participant 2) | |

| B: Intervention language | |

| B1: Interventions should use simple, conceptually straightforward, positive messages | Well you know you're in the moment, so it's like it's not even gonna help, give me somethin’ for now. When I want advice, I want quick advice that's gonna like just help me right there. (Participant 20) |

| And that'd be good to get something positive. Because when you're having a really bad day it's like I really want something positive. (Participant 11) | |

| It could help—it reminds them to think like things—it's, it helps you, it like gives you like more positive things that you can do to avoid the negative, to like think before you speak, think before you act. (Participant 19) | |

| B2: The tone of an intervention should be conversational and friendly but not slang filled | I just don't want like teacher comments—like text messages. Like that's somethin’ that's annoying. I wouldn't want that; I'd kinda be mad, like, “C'mon, now.” So yeah, like stuff like that, then yeah, definitely. (Participant 20) |

| So to make it [sound] more like, we're kind of, “we already know each other and we're friends and we're texting, just between us.” (Participant 7) | |

| Like if you add exclamation points at the end of everything that's gonna seem really, really uppity. (Participant 6) | |

| C: Intervention structure | |

| C1: The messages may be automated but must be individually tailored with some two-way communication | Sometimes, like, you—sometimes sending a quote to somebody, like, they might not be feeling that way. So it's like, you'll be like ‘Oh, how are you feelin’ today?’ and then if you say a certain way, it's like, you give ‘em a text message that relates to that. (Participant 9) |

| Like I would just want you—like, me, to, like me, like say if it was you texting me “Oh, how are you feelin’ today?” Like, I would like that, because, like, it's from you and, like, if you were textin’ all the other girls the same thing, it's just weird to me. (Participant 15) | |

| C2: The intervention should deliver both predetermined (automatic) and as-needed messages | [I'd like it if] when they're upset, they can just, like, hit up that app and be like, I feel like this right now. And then this is why. And then [the program] answers back, well, maybe you should do this. How, like, on a scale from one to ten, why do you feel like this? Like, stuff like that. (Participant 17) |

| So like I said, some people might need more than others. So if they need ‘em they [should have the option to] could always get more. (Participant 18) | |

| C3: Participants perceive advantages to both randomly delivered content and regularly scheduled content | It'd be nice to have every day um, to have one. Like in the morning maybe. And maybe even at night because now in the morning you've had this. But if you have a rough day it'd be nice to know something at the end of the day. (Participant 11) |

| I think you should—I think you guys should like scatter it, make it random. ‘Cuz then like, you don't want them to be like expecting it, so then, uh, like they know. I think like being reminded like randomly or like with them not knowing – then it would be better, because you don't want them to like think, like know that they are gonna get it, because then it won't like help them. (Participant 19) | |

| C4: The dose and schedule of intervention content may need to be varied according to the participant's needs | ...when they get it more and more it might be helpful for them to say, oh well, I guess that's good about me. I guess I can do that. (Participant 11) |

| Like I said depends on the person. I wouldn't mind if it would be everyday, [or] if it would be once a week, like, Doesn't matter. (Participant 2) | |

| Um, maybe, like, Friday after school or at nighttime right before kids start getting into trouble. ‘Cuz, um, that's when, you know, when kids are going to get in trouble. Most of the time, they don't get in trouble during the week unless it'sat school, when they do something wrong at school, but when you don't have to go to school and you're kind of on your own, then that's kind of where, you know, emotions rise and whatever. (Participant 13) | |

| However long you need it. Like, everybody's different, but it could definitely help a lot of people in stressful situations make better decisions. (Participant 17) | |

| I think it depends on the per—the way the, who the person is, how they—like their personality. ... And if, like ifthe time comes up to like maybe how long they said, and if they are still not ready, just keep ‘em going for however long they want. (Participant 19) | |

| C5: Multimedia may be helpful but is not necessary | Like, funny pictures. Like, when you're upset, like, they're called anxiety pictures. So it's like, whenever you're, like, upset and you're about to have an anxiety attack, you look at a picture, laugh, and you're just like—[relaxed]. (Participant 17) |

| [To RA question “Is there anything else that you would like?”] Uhm, smiley faces! (Participant 16) | |

Potential for intervention acceptability/feasibility

Theme A1: High-risk adolescent females are receptive to a proposed violence prevention intervention

The interviewees were almost universally enthusiastic about a text message-based violence prevention intervention: “It's like fresh... It's like someone who's—dactually like just cares about how you're doing” (participant 9). Several participants left the interview requesting that the interviewer contact them when the program was ready to be used. Two participants with extremely low levels of violence said that although they might not enroll in the intervention themselves, they would recommend it to friends: “I don't think I would personally... But I know that there's a bunch of girls who would ...” (participant 5). Others encouraged investigators to develop the program for boys as well.

Several participants spontaneously described how sending/receiving encouraging texts from friends plays into their current violence prevention strategies. They said that they already saved supportive or inspirational messages from friends, aunts, and mothers to help them avoid fights. They stated that the program, as proposed, would serve as an extension of their current coping strategies: “it'd be like an extra friend, you know?” (participant 7).

Theme A2: There were no concerns about stigma and time, but participants did articulate a few concerns about privacy and cost

Participants reported a few concerns about the use of a text message-based intervention. Almost all the girls had unlimited text programs and felt that message frequency would not be an issue. A single participant, however, mentioned that the cost of texting might alter her usage of the program. Although privacy was not a major concern, a few girls felt that it was important to remind participants that we'd be “just keepin’ it between us, like, whatever I tell you” (participant 15); one interviewee also felt that we should remind participants that others could read messages on their phone if they weren't deleted. Nonetheless, no one feared that the program would be stigmatizing. One girl even stated, “...it's, it's not like a big deal. It's just like text messages. It's not like you have to like go somewhere to get positive like a counselor. It's something that's like there, just a little side thing to help you” (participant 19).

Theme A3: Having an intervention recommended to them by others would increase program uptake

Peer recommendations were repeatedly said to have the most weight in increasing program use. Many teens said that if the messages were particularly helpful, they would consider forwarding them to friends to assist them too. Most participants felt that a doctor's recommendation would increase the likelihood that they would use the program, although one high-risk girl (reporting 25 violent episodes in the past year) said a doctor recommendation would be “annoying” (participant 20). Regardless, participants emphasized that the program should be introduced in-person or online prior to enrollment: “I think it would be good to know like who's doing the program and why. Cuz people could might think that's creepy [otherwise]” (participant 11).

Intervention language

Theme B1: Interventions should use simple, conceptually straight forward, positive messages

Participants emphasized that intervention language should be simple: “It doesn't have anything hard for the person to really think about, cuz to tell you the truth when they are upset and when they are angry, big words are just gonna be like ‘whatever, just don't just don't talk anymore’” (participant 2). Positively worded messages were most enthusiastically endorsed. Most participants said that they would tune out negatively toned texts and requested rewording into an encouraging tone: “Like you need someone to motivate you and let you know that you can you get through it even though right now it's really, really hard” (participant 10).

Theme B2: The tone of an intervention should be conversational and friendly but not slang filled

Participants encouraged messages that would sound “like, something that I would say” (participant 7) rather than like something a counselor or teacher would say. Similarly, they emphasized that the program should have a nonjudgmental, conversational tone. One participant stated: “Just don't make it seem robotic... So just try and make it seem like you're talking to that person. Like you're actually having a conversation with that person even though the messages are automated” (participant 6). In contrast, language that was perceived as “teen talk”—particularly text-message abbreviations and slang—were often disliked by participants.

Intervention structure

Theme C1: The messages may be automated but must be individually tailored with some two-way communication

As an extension of Theme B2, participants universally stated that although they understand that the program would be automated, they wanted their messages to be individualized: “I don't want [that] everybody else is getting the same exact answers I'm getting” (participant 5). Participants suggested that the program should first ask them how they are feeling and then offer a message according to their mood that day.

Theme C2: The intervention should deliver both predetermined (automatic) and as-needed messages

Many participants endorsed a feature to “request” text messages when they were feeling particularly stressed or angry. All participants said that some automatically delivered messages would be useful, as they may not remember to request messages when they need them: “But if you had gotten a text earlier that day saying ‘stop and think’ and you just happened to remember it before you got in a fight you'd be like oh, you know what, I'm not going to get in this fight... But you're not going to stop and check your phone right before you beat someone up” (participant 6).

Theme C3: Participants perceive advantages to both randomly delivered content and regularly scheduled content

When discussing ideal schedules for the predetermined messages, most participants preferred a random delivery schedule because “randomly would make it more personable. Um, like it wouldn't feel like an alarm clock” (participant 7) and because random delivery would be “kind of almost like a surprise, like, waiting for you...Like-like a boost when you don't even need it but you can put it away for later” (participant 12). Others cited random delivery as important for avoiding unpredictable stressors. Participants also felt that a random delivery schedule would minimize the potentially “robotic” nature of an automated program.

Nonetheless, some participants felt that regularly scheduled delivery of intervention content would be more helpful in establishing a sustained change in behavior. One girl stated that she would develop a habit of thinking about effective strategies at a certain point each day: “if you've been having [the text at] 6:00 every day for the past three weeks all of a sudden you're gonna stop and think because you get those texts at 6:00”(participant 6). When participants who wanted the random delivery of texts were prompted to choose a schedule, most felt that a message in the morning could be helpful to set the tone for the day.

Theme C4: The dose of intervention content may need to be varied according to the participant's needs

Participants suggested a variety of lengths for the program, ranging from 1 month to “as long as I need it” (about half of the participants). Participants stated that they were generally willing to receive multiple text messages per day, with higher-risk girls desiring more frequent messages. Some participants mentioned that teens’ commitment to the intervention and desired frequency of messages may increase with time.

Theme C5: Multimedia may be helpful but is not necessary

Some participants encouraged a multimedia component to the intervention (e.g., funny cat pictures and videos). Indeed, a few participants stated that multimedia was essential: “Cuz this generation most people have Androids and stuff. You can—people change mostly because they don't want to have whack [bad or outdated] phones or something” (participant 2).

Discussion

In this article, we present novel qualitative data about essential format, structure, and acceptability elements of a text message-based preventive intervention for high-risk adolescents. Most importantly, this study supports that a text message-based preventive intervention would potentially be well received by high-risk female adolescents in the ED. In fact, many participants felt a text-message violence prevention program could provide a trustworthy support otherwise missing from their lives. They articulated a strong desire for easily accessible content to help them navigate the day-to-day interpersonal stressors in their lives, and the sense that a text-message intervention could serve this function well. These findings speak both to the lack of current preventive interventions available to high-risk teens and to the potential suitability of the text-message format for delivery of such an intervention.

Although most teens were not concerned about privacy and confidentiality, a few participants emphasized that this topic should be explicitly discussed at the beginning of a text-message intervention. One teen even commented on the importance of managing stored text messages (e.g., changing pass codes, etc.). Nonetheless, the teens overall felt comfortable discussing potentially sensitive information via text messaging. This finding may reflect teens’ desensitization to technology's impact on privacy in general [31,32].

The participants’ emphasis on the importance of tailoring and personalization—aspects currently missing from many mHealth interventions [33]—is noteworthy. For instance, participants’ biggest concern about acceptability was that the intervention should not be too “robotic” and should seem to really care about how they were feeling. Similarly, their biggest concern about content was that it should reflect how they were actually feeling that day. Their most consistent opinion about the intervention's structure was that it should be responsive to their individual needs (i.e., random vs. prescheduled delivery; ability to request as-needed messages as well as to receive prescheduled messages; and ability to continue the program as long as desired). These themes herald the importance of increased use of tailoring algorithms in the development of text-message programs, similar to the importance of tailoring in other forms of technology-based interventions [33,34]. They may also explain the lack of long-term adherence to some text-message interventions, which had limited tailoring of the intervention [33]. Ideal intervention content may need to reflect participants’ day-to-day changing needs.

That said, tailoring based on baseline characteristics may still be important. For instance, higher-risk participants may both want and need a more intense intervention, with more frequent delivery of intervention messages. Future work is needed to determine whether those with higher baseline risk are adherent to intense interventions and whether these types of interventions are efficacious [35,36].

Participants’ preferences about language and tone were similar to prior studies of text message-based interventions for adolescents’ nutrition/physical activity in Arizona [37] and marijuana use in Denmark [38]. Teens in our qualitative analysis, as well as these two prior studies, preferred simple, straightforward, positively engaging messages. Our study's participants also walked a similarly fine line regarding tone: they wanted messages from a trusted source but disliked a tone that was overly authoritative. The universality of these findings, from a variety of geographic locations and on a variety of topics, supports the importance of engaging teens in creation of their own content. It may be difficult for a researcher or clinician to accurately choose simple, trustworthy, but nonauthoritative language for teens.

From the ED perspective, participants’ increased willingness to use the intervention after recommendation from a doctor is encouraging. It would be important to introduce the intervention as a program designed with the input and voices of peers, since peer support was identified as the most important factor in the decision to use the intervention. This parallels standard behavioral intervention techniques of highlighting peer norms [39].

Finally, only half of this study's participants currently have smartphones (consistent with other studies) [10,40]. Participants’ comments suggest that future studies may wish to consider multimedia or “application”-based interventions to enhance the text-message content. However, low rates of the use of smartphones may reduce the generalizability of an “app”-based intervention. This finding corresponds with observations from others’ formative work on mHealth interventions for teens [37].

Limitations

This study was conducted at a single urban center, potentially limiting generalizability. Although participation reflected the demographics of our ED, and interviews continued until saturation was reached, it is possible that different themes would arise with participants in other settings. In addition, our study was conducted with only female participants, yet males may have different acceptability needs. Some participants mentioned including boys as intervention participants. This may be worth exploring in future studies. However, it is necessary to employ a similar formative research process prior to intervention design; adolescent male's perceptions of a text message-based intervention acceptability, language, and format may differ greatly from those of the adolescent females. Finally, non-English-speaking patients were ineligible to participate in the research study, limiting applicability to them.

This qualitative analysis provides valuable information that may optimize acceptability of a text message-based preventive intervention for high-risk adolescent females presenting to the ED. Participants noted preferences for two-way texting and individualized delivery schedules. Content should be tailored according to both baseline and day-to-day characteristics, should be positively worded, and should be conversational in tone. A few concerns about cost and privacy were articulated; to ensure broad acceptance, these concerns should be addressed in intervention design.

IMPLICATIONS AND CONTRIBUTION.

This study presents novel information on high-risk adolescent females’ perspectives on a potential text message-based preventive intervention. Personalized schedule, dose, and content are of paramount importance. Teens desired peer endorsement and a conversational tone. These findings can assist future mHealth researchers in designing acceptable and feasible text-message interventions.

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge Christina Sales, Cathy Nam, Eve Purdy, and Alexandra Pierszak for their dedication to patient recruitment and Sarah Bowman for her assistance with coding.

Funding Support

This research was funded by the Society for Academic Emergency Medicine Research Training Grant and University Emergency Medicine Foundation. Dr. Ranney received salary support from NIMH (grant K23 MH095866) during the time that the article was being written.

References

- 1.U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Health information technology and quality improvement [Dec 3, 2013];What is mHealth? Available at: http://www.hrsa.gov/healthit/mhealth.html.

- 2.Atienza A, Patrick K. Mobile health: The killer app for cyberinfrastructure and consumer health. Am J Prev Med. 2011;40(5 Suppl 2):S151–3. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2011.01.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Heron KE, Smyth JM. Ecological momentary interventions: Incorporating mobile technology into psychosocial and health behaviour treatments. Br J Health Psychol. 2010;15(Pt 1):1–39. doi: 10.1348/135910709X466063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fjeldsoe BS, Marshall AL, Miller YD. Behavior change interventions delivered by mobile telephone short-message service. Am J Prev Med. 2009;36:165–73. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2008.09.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kumar S, Nilsen WJ, Abernethy A, et al. Mobile health technology evaluation: The mHealth evidence workshop. Amer J Prev Med. 2013;45:228–36. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2013.03.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wilson KM, Klein JD. Adolescents who use the emergency department as their usual source of care. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2000;154:361–5. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.154.4.361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cunningham R, Knox L, Fein J, et al. Before and after the trauma bay: The prevention of violent injury among youth. Ann Emerg Med. 2009;53:490–500. doi: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2008.11.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fein JA, Ginsburg KR, McGrath ME, et al. Violence prevention in the emergency department: Clinician attitudes and limitations. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2000;154:495–8. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.154.5.495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rhodes KV. Mood disorders in the emergency department: The challenge of linking patients to appropriate services. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2008;30:1–3. doi: 10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2007.10.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ranney ML, Choo EK, Spirito A, et al. Adolescents’ preference for technology-based emergency department behavioral interventions: Does it depend on risky behaviors? Pediatr Emerg Care. 2013;29:475–81. doi: 10.1097/PEC.0b013e31828a322f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ranney ML, Choo EK, Wang Y, et al. Emergency department patients’ preferences for technology-based behavioral interventions. Ann Emerg Med. 2012;60:218–27. e48. doi: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2012.02.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lenhart A, Ling R, Campbell S, et al. Teens and mobile phones. [Dec 3, 2013];Pew Internet and American Life Project. 2010 Available at: http://pewinternet.org/w/media//Files/Reports/2010/PIP-Teens-and-Mobile-2010.pdf.

- 13.Reid SC, Kauer SD, Dudgeon P, et al. A mobile phone program to track young people's experiences of mood, stress and coping. Development and testing of the mobiletype program. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2009;44:501–7. doi: 10.1007/s00127-008-0455-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Suffoletto B, Akers A, McGinnis KA, et al. A sex risk reduction text-message program for young adult females discharged from the emergency department. J Adolesc Health. 2013;53:387–93. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2013.04.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Suffoletto B, Callaway C, Kristan J, et al. Text-message-based drinking assessments and brief interventions for young adults discharged from the emergency department. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2012;36:552–60. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2011.01646.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Riley WT, Rivera DE, Atienza AA, et al. Health behavior models in the age of mobile interventions: are our theories up to the task? Transl Behav Med. 2011;1:53–71. doi: 10.1007/s13142-011-0021-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nilsen W, Kumar S, Shar A, et al. Advancing the science of mHealth. J Health Commun. 2012;17(Suppl 1):5–10. doi: 10.1080/10810730.2012.677394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lenhart A. [December 3, 2013];Teens, smartphones, and texting. Pew Internet & American Life Project. 2012 Available at: http://pewinternet.org/Reports/2012/Teens-and-smartphones.aspx.

- 19.Militello LK, Kelly SA, Melnyk BM. Systematic review of text-messaging interventions to promote healthy behaviors in pediatric and adolescent populations: Implications for clinical practice and research. Worldviews Evid Based Nurs. 2012;9:66–77. doi: 10.1111/j.1741-6787.2011.00239.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ranney ML, Whiteside L, Walton MA, et al. Sex differences in characteristics of adolescents presenting to the emergency department with acute assault-related injury. Acad Emerg Med. 2011;18:1027–35. doi: 10.1111/j.1553-2712.2011.01165.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.NIH State-of-the-Science Conference Statement on preventing violence and related health-risking social behaviors in adolescents. NIH Consens State Sci Statements. 2004;21:1–34. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Straus MA, Hamby SL, Boney-McCoy S, et al. The revised conflict tactics scales (CTS2): Development and preliminary psychometric data. J Fam Issues. 1996;17:283–316. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Walton MA, Chermack ST, Shope JT, et al. Effects of a brief intervention for reducing violence and alcohol misuse among adolescents: A randomized controlled trial. Jama. 2010;304:527–35. doi: 10.1001/jama.2010.1066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lowe B, Kroenke K, Grafe K. Detecting and monitoring depression with a two-item questionnaire (PHQ-2). J Psychosom Res. 2005;58:163–71. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2004.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cunningham RM, Walton MA, Goldstein AL, et al. Three-month follow-up of brief computerized and therapist interventions for alcohol and violence among teens. Acad Emerg Med. 2009;16:1193–207. doi: 10.1111/j.1553-2712.2009.00513.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JBW, et al. The Patient Health Questionnaire somatic, anxiety, and depressive symptom scales: A systematic review. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2010;32:345–59. doi: 10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2010.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Richardson LP, Rockhill C, Russo JE, et al. Evaluation of the PHQ-2 as a brief screen for detecting major depression among adolescents. Pediatrics. 2010;125:e1097–103. doi: 10.1542/peds.2009-2712. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Braun V, Clarke V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual Res Psych. 2006;3:77–101. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Giacomini MK, Cook DJ. Users’ guides to the medical literature: XXIII. Qualitative research in health care A. Are the results of the study valid? Evidence-Based Medicine Working Group. Jama. 2000;284:357–62. doi: 10.1001/jama.284.3.357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lincoln YS, Guba EG. Naturalistic inquiry. Sage Publications, Inc; Beverly Hills, CA: 1985. [Google Scholar]

- 31.O'Sullivan LF. Open to the public: How adolescents blur the boundaries online between the private and public spheres of their lives. J Adolesc Health. 2012;50:429–30. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2012.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Madden M, Lenhart A, Cortesi S, et al. Teens and mobile apps privacy. Pew Research Center; Washington, DC: [December 3, 2013]. Available at: http://www.pewinternet.org/Reports/2013/Teens-and-Mobile-Apps-Privacy.aspx. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Head KJ, Noar SM, Iannarino NT, et al. Efficacy of text messaging-based interventions for health promotion: A meta-analysis. Social Sci Med. 2013;97:41–8. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2013.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kreuter MW, Wray RJ. Tailoredand targeted healthcommunication: Strategies for enhancing information relevance. Am J Health Behav. 2003;27:S227–32. doi: 10.5993/ajhb.27.1.s3.6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Gallagher K, Updegraff J. Health message framing effects on attitudes, intentions, and behavior: A meta-analytic review. Ann Behav Med. 2012;43:101–16. doi: 10.1007/s12160-011-9308-7. 2012/02/01. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hawkins RP, Kreuter M, Resnicow K, et al. Understanding tailoring in communicating about health. Health Education Res. 2008;23:454–66. doi: 10.1093/her/cyn004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hingle M, Nichter M, Medeiros M, et al. Texting for health: The use of participatory methods to develop healthy lifestyle messages for teens. J Nutr Educ Behav. 2013;45:12–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jneb.2012.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Laursen D. Counseling young cannabis users by text message. J Computer-Mediated Communic. 2010;15:646–65. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Abraham C, Michie S. A taxonomy of behavior change techniques used in interventions. Health Psychol. 2008;27:379–87. doi: 10.1037/0278-6133.27.3.379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Madden M, Lenhart A, Duggan M, et al. [Dec 3, 2013];Teens and technology. Pew Internet and American Life Project. 2013 Available at: http://www.pewinternet.org/Reports/2013/Teens-and-Tech.aspx.