Abstract

This study investigated the possible role of the ApoE receptors Lrp1 and Apoer2 in mediating the pathological effects of ApoE4 in ApoE-targeted-replacement mice expressing either the human ApoE3 or ApoE4 allele. In this study we show that activation of the amyloid cascade by inhibition of the Aβ-degrading enzyme neprilysin results in up-regulation of the ApoE receptor Lrp1 in the CA1 hippocampal neurons of 4-month-old ApoE4 mice, but not in the corresponding ApoE3 or ApoE-deficient (KO) mice. These results are in accordance with the previous findings that activation of the amyloid cascade induces Aβ accumulation in the CA1 neurons of ApoE4 mice, but not in ApoE3 or ApoE-KO mice. This suggests that the apoE4-driven elevation of Lrp1 is mediated via a gain of function mechanism and may play a role in mediating the effects of ApoE4 on Aβ. In contrast, no changes were observed in the levels of the corresponding Apoer2 receptor following the neprilysin inhibition.

The ApoE receptors of naive ApoE4 mice were also affected differentially and isoform specifically by ApoE4. However, under these conditions, the effect was an ApoE4-driven reduction in the levels of Apoer2 in CA1 and CA3 pyramidal neurons, whereas the levels of Lrp1 were not affected.

RT-PCR measurements revealed that the levels of Apoer2 and Lrp1 mRNA in the hippocampus of naïve and neprilysin-inhibited mice were not affected by ApoE4, suggesting that the observed effects of ApoE4 on the levels of these receptors is post-transcriptional. In conclusion, this study shows that the levels of hippocampal ApoE receptors Lrp1 and Apoer2 in vivo are affected isoform specifically by ApoE4 and that the type of receptor affected is context dependent.

Keywords: Alzheimer's disease (AD), amyloid-β, Apoer2, apolipoprotein E4 (ApoE4), targeted replacement mice, Lrp1

Introduction

Alzheimer disease (AD) is characterized by cognitive decline and by the occurrence of brain senile plaques and neurofibrillary tangles (NFT), as well as synapse and neuronal loss in the brain. The senile plaques contain a 40–42-amino acid-long amyloid-beta (Aβ) peptide derived from a precursor protein (APP) [1], the NFT contain abnormal hyperphosphorylated aggregates of the microtubule-associated protein tau. Genetic studies revealed allelic segregation of the apolipoprotein E (ApoE) gene to families with a higher risk for late onset AD [2–4]. There are three major alleles of ApoE, termed E2 (ApoE2), E3 (ApoE3) and E4 (ApoE4), of which ApoE4 is the main AD risk factor. The frequency of ApoE4 in sporadic AD is about 60%, and it increases the risk for AD by lowering the age of onset of the disease by 7 to 9 years per allele copy [3]. Declining memory and brain pathology have been reported in middle-aged and young ApoE4 carriers, with ongoing normal clinical status [5–7], suggesting that the pathological effects of ApoE4 start long before its clinical manifestations in AD.

ApoE4 is associated with increased deposition of Aβ in AD [8; 9], with impaired neuronal plasticity and with increased neuropathology [10; 11]. The findings that Aβ deposition is specifically elevated in ApoE4-positive AD patients and cellular and animal model studies, which showed that ApoE4 and Aβ interact synergistically [12–17], led to the suggestion that the pathological effects of ApoE4 are mediated by cross-talk interactions with the amyloid cascade [18; 19]. Accordingly, we have shown that activation of the amyloid cascade in ApoE4- and ApoE3-targeted replacement mice by prolonged inhibition of the Aβ-degrading enzyme neprilysin specifically induces the accumulation of ApoE, Aβ and Aβ oligomers in activated lysosomes of CA1 hippocampal neurons in the ApoE4 mice. This in turn leads to synaptic and neuronal loss and subsequently to cognitive impairments [12–14; 20].[13; 20][13; 20][13; 20][13; 20] The central role of ApoE in the transport and delivery of brain lipids together with the findings that ApoE3 and ApoE4 interact differentially with lipids [21] and that the pathological effects of ApoE4 in the mouse can be rescued by a fish oil (DHA) diet [22], led to the proposal that the pathological effects of ApoE4 are mediated via lipid-related mechanisms. In addition, it has been suggested that the toxicity of ApoE4 is mediated via proteolytic fragments that are generated specifically during the catabolism of ApoE4 [23].

We have recently shown that young naïve ApoE4 mice are cognitively impaired and that this is associated with synaptic loss in the hippocampus and with the accumulation of Aβ and hyperphosphorylated tau in the affected neurons [24]. The relative contribution of the non-mutually exclusive ApoE4-driven pathological mechanisms discussed above, to the ApoE4-derived phenotype depends on the pathophysiological context, e.g., the steady-state situation in naïve mice versus an acute response to activation of the amyloid cascade or to head injury [20; 25].

The effects of ApoE are mediated via a family of cell surface receptors known as the low density lipoprotein receptor (LDLR family), which play a role in diverse functions including cholesterol metabolism, neuronal migration, cell signaling and endocytosis [26]. These receptors contain a large N-terminal extracellular domain with multiple repeat motifs that can bind ApoE and additional ligands, and a small C-terminal cytoplasmatic domain that mediates the effects of the activated receptors intracellularly [27]. The LDL receptor family members differ from each other by the size and ligand binding site properties of their N-terminal as well as by their C-terminal-related properties such as accessibility and binding to distinct chaperon proteins. The biochemical complexity of the LDL receptors and the wide scope of their physiological functions call for an examination of the possibility that the isoform-specific effects of ApoE4 in vivo may be driven by isoform-specific interactions of ApoE with distinct ApoE receptors, namely, LDL receptor-related protein 1 (Lrp1) and LRP8 (Apoer2), as was shown in cell culture studies. Lrp1 is highly expressed in neurons of the CNS and undergoes constitutive rapid endocytosis to transport ApoE lipids and other ligands from the cell surface to intracellular compartments [27; 28]. Lrp1 also plays a role in a large number of signal transduction systems such as PKCδ and GSK3β signaling [27; 29; 30], which are involved in learning and memory processes. In addition, Lrp1 plays an important role in the clearance of Aβ and the regulation of tau phosphorylation [31–36]. Apoer2, which was first discovered as a key member of reelin signaling, is crucial for neuronal migration and development and is now recognized as a key player in the adult nervous system where it plays important roles in synaptic plasticity and neuronal signaling [37–41]. Cell culture studies revealed that Lrp1 and Apoer2 and their downstream effects are affected differentially by ApoE4 and ApoE3 [17; 29; 42–44]. The extent to which these in vitro effects occur in vivo and their possible role in mediating distinct features of the ApoE phenotype are not known.

This study investigates the possible roles of Lrp1 and Apoer2 in mediating the pathological effects of ApoE4 in vivo and the extent to which this depends on the pathophysiological context. Accordingly, the experiments investigate the effects of ApoE4 in young naïve ApoE3- and ApoE4-targeted replacement mice and following the activation of the amyloid cascade, on the levels and spatial distribution of Apoer2 and Lrp1 in the hippocampus and the extent to which they correlate with the neuronal ApoE4 phenotype.

Materials and Methods

Transgenic mice

ApoE-target replacement mice, in which the endogenous mouse ApoE was replaced by either human ApoE3 or ApoE4, were created by gene targeting, as previously described [45]. The mice used were purchased from Taconic (Germantown, NY). Mice were back-crossed to wild-type C57BL/6J mice (Harlan 2BL/610) for ten generations and were homozygous for the ApoE3 (3/3) or ApoE4 (4/4) alleles. These mice are referred to in the text as ApoE3 and ApoE4 mice, respectively. The ApoE genotype of the mice was confirmed by PCR analysis, as described previously [14; 46]. All the experiments were performed on 4-month-old male animals and were approved by the Tel Aviv University Animal Care Committee. Every effort was made to reduce animal stress and to minimize animal usage.

Activation of the amyloid cascade

Alzet® mini-osmotic pumps (model 2004, which deliver their contents at 0.25 µl/h for up to 30 days) were loaded with the neprilysin inhibitor thiorphan (0.5 mM; Sigma) in artificial cerebrospinal fluid containing 1 mM ascorbic acid or with a similar solution without thiorphan ("sham"). The Alzet pumps were implanted with a brain infusion cannula inserted into the lateral ventricle as previously described [13].

Immunofluorescence confocal microscopy

Mice were anesthetized with ketamine and xylazine and perfused transcardially with saline and then with 4% paraformaldehyde in 0.1M phosphate buffer, pH 7.4. Their brains were removed, fixed overnight in 4% paraformaldehyde in 0.1M phosphate buffer, pH 7.4, and then placed in 30% sucrose for 48 h. Frozen coronal sections (30µm) were then cut on a sliding microtome, collected serially, placed in 200µl of cryoprotectant, and stored at −20°C until use. The free-floating sections were immunostained with the following primary antibodies (Abs): Goat anti-cathepsin D (CatD, 1:500, Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz); Rabbit anti-Lrp1 (αCT; J. Herz lab [47]; 1:1000); and Rabbit anti-Apoer2 (αCT; J. Herz lab [48]; 1:1000). Immunofluorescence staining was performed using fluorescent chromogens. Accordingly, sections were first blocked (incubation with 20% normal donkey serum in PBS containing 0.1% triton X-100 (PBST) for 1 h at room temperature), and then reacted for 48 h at 4°C with the primary antibodies (dissolved in 2% normal donkey serum in PBST). Next, the bound primary antibodies were visualized by incubating the sections for 1 h at room temperature with Alexa-fluor 488-conjugated donkey anti-rabbit (1:1000; Invitrogen, Eugene, OR), or Alexa-fluor 647-conjugated donkey anti-goat (1:1000; Invitrogen), depending on the appropriate initial antibody. The sections were then mounted on dry gelatin-coated slides. All sections were stained simultaneously with a specific Ab and visualized using a confocal scanning laser microscope (Zeiss, LSM 510). Images (1024×1024 pixels, 12 bit) were acquired by averaging eight scans. Control experiments revealed no staining in sections lacking the first antibody. The intensities of Immunofluorescence staining, expressed as the percentage of the area stained, were calculated utilizing the Image-Pro Plus system (version 5.1, Media Cybernetics) as previously described [13]. All images for each immunostaining were obtained under identical conditions, and their quantitative analyses were performed with no further handling. Moderate adjustments for contrast and brightness were performed evenly on all the presented images of the different mouse groups. The images were analyzed by setting a threshold for all sections with a specific labeling. The area of the staining over the threshold compared to the total area of interest was determined for each mouse and each group was averaged. For the Lrp1 and CatD co-localization experiments, each image was first analyzed separately. The co-localizations of Lrp1 and CatD were then determined as the area in which both antibodies showed staining over the respective thresholds.

RT-PCR analysis

Mice were sacrificed at the age of 4 months and intracardially perfused with saline. Their brains were removed and frozen over liquid nitrogen and were kept at −70°C until use. In the neprilysin inhibition experiments the brains were put in a frozen metal mold. 500um sections were then prepared, after which the CA1 region was removed from the relevant sections (Bregma -2.5 to -3) and the sections were transferred immediately to liquid nitrogen. RNA was extracted from the tissue using the MasterPure RNA purification kit (Epicentre, USA). RNA was transformed into cDNA using the High Capacity cDNA reverse transcription kit (Applied Biosystems, USA). The brains of the naïve non-treated mice were treated similarly except that RNA was extracted from snap frozen whole hippocampi whose RNA was extracted and processed as described above. TaqMan qRT PCR assays were conducted according to the manufacturer's specifications (Applied Biosystems). Oligonucleotides (probes) for TaqMan qRT PCR were attached to FAM (6-carboxyfluorescin) at the 5' end and a quencher dye at the 3' end. Lrp1 and Apoer2 gene expression levels were determined utilizing TaqMan RT-PCR specific primers (Applied Biosystems). Analysis and quantification were conducted using 7300 system software and compared to the expression of the Hprt-1 housekeeping gene.

Statistical Analysis

Values are presented as mean ± SEM. Student’s t-test was performed to compare mean values of the naïve ApoE3 and ApoE4 mice, whereas 2-way ANOVA, with the appropriate post hoc analysis, was performed to compare the results of the neprilysin inhibited and sham treated ApoE4 and ApoE3 mice. Significant difference between groups was set at P<0.05.

Results

1. The effects of ApoE4 on ApoE receptors in young naïve mice

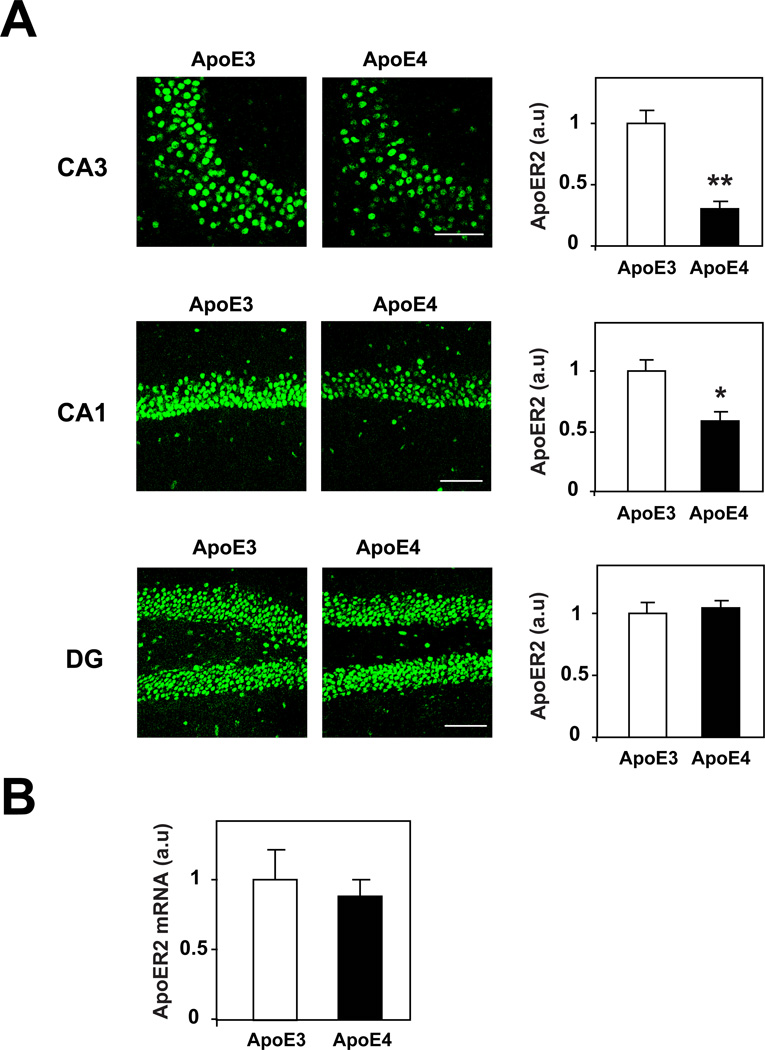

The possibility that the levels of brain ApoE receptors in young (4-month-old) mice are affected isoform-specifically by ApoE4 was investigated in the hippocampus and focused first on Apoer2. As shown in figure 1, the CA1, CA3, and DG hippocampal sub-fields of the ApoE4 and ApoE3 mice stained positively for the ApoE receptor Apoer2. This staining covered the whole perikarya and in the DG it was present primarily in the granular cells and less in the hilus. The levels of Apoer2 were significantly lower in the CA3 and CA1 neurons of the ApoE4 mice than in those of the corresponding ApoE3 mice (P<0.0001 for CA3 and P<0.005 for CA1). In contrast, the levels of Apoer2 in the DG were similar in the ApoE4 and ApoE3 mice (Fig. 1A). RT-PCR experiments revealed no differences in hippocampal Apoer2 mRNA levels between the ApoE4 and ApoE3 mice (Fig. 1B), suggesting that the ApoE4-driven decrease in Apoer2 is post transcriptional.

Figure 1. The levels of the ApoE receptor Apoer2 in the hippocampus of young, naïve ApoE4 and ApoE3 mice.

(A) Anti-Apoer2 immunohistochemistry. Brains of 4-month-old ApoE4 and ApoE3 mice were processed for immunohistochemistry and stained with an anti-Apoer2 Ab, as described in Materials and Methods. Representative images of the hippocampal CA3 and CA1 and DG sub-fields from ApoE4 and ApoE3 mice are presented in the panels on the left, whereas quantification of the results by computerized confocal microscopy imaging analysis (mean+/−SEM; n=20 mice /group) is presented on the right panel. Empty and filled bars correspond, respectively, to the ApoE3 and ApoE4 mice. * indicates P<0.005 and ** indicates P<0.0001 for comparisons of the results of the two mouse groups by Student's t-test. Scale bar = 80 microns. (B) Apoer2 RT-PCR. Hippocampi from 4-month-old ApoE4 and ApoE3 mice were rapidly excised and snap frozen in liquid nitrogen, after which their Apoer2 mRNA levels were determined by RT-PCR, as described in Materials and Methods. Results presented are the mean+/−SEM of 5 mice /group. Empty and filled bars correspond, respectively, to ApoE3 and ApoE4 mice.

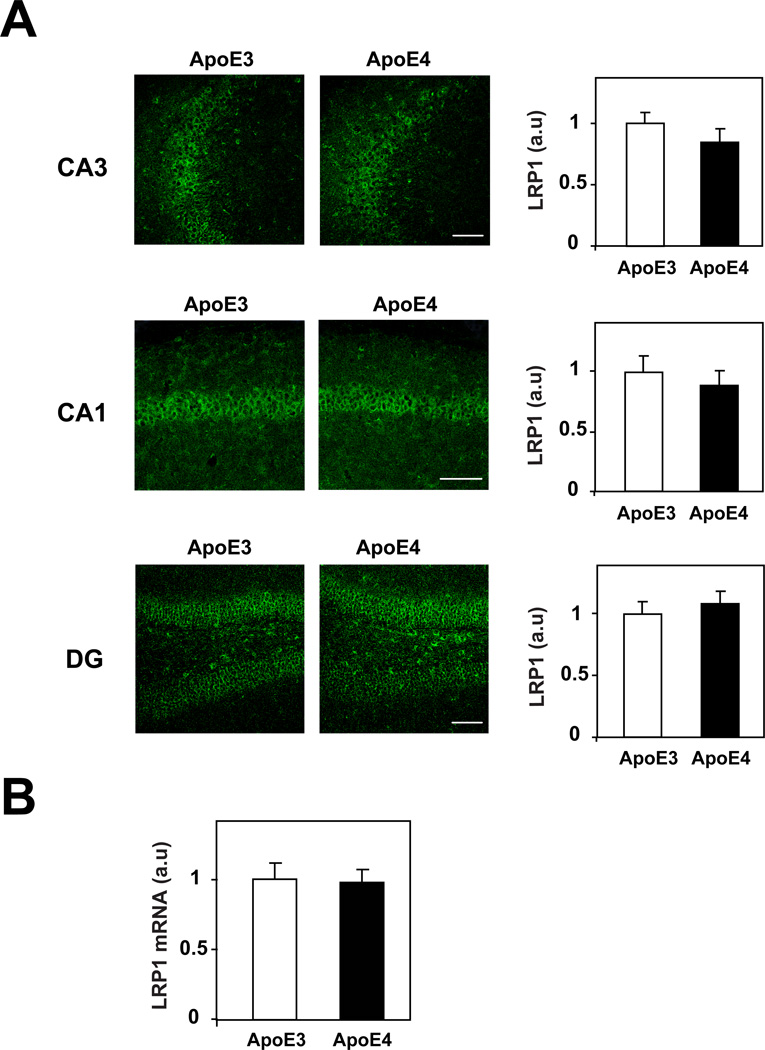

The levels and spatial distribution of Lrp1 in the hippocampi of ApoE4 and ApoE3 mice are depicted in Figure 2. As can be seen, the CA3 and CA1 pyramidal neurons of both the ApoE4 and ApoE3 mice stained positively for Lrp1, whose cellular location was perinuclear. The DG also stained positively for Lrp1, in both mouse groups. This was apparent in the blades of the DG as well as in large neurons and neuronal processes in the hilus. Quantification of these results revealed that the levels of Lrp1 in all hippocampal sub-fields, unlike those of Apoer2, were not affected by the ApoE genotype (Fig. 2A). RT-PCR experiments also revealed no differences in hippocampal Lrp1 mRNA between the ApoE4 and ApoE3 mice (Fig. 2B).

Figure 2. The levels of the ApoE receptor Lrp1 in the hippocampus of young and naïve ApoE4 and ApoE3 mice.

(A) Anti-Lrp1 immunohistochemistry. Brains of 4-month-old ApoE4 and ApoE3 mice were processed for immunohistochemistry and stained with an anti-Lrp1 as described in Materials and Methods. Representative images of the hippocampal CA3 and CA1 and DG sub-fields from ApoE4 and ApoE3 mice are presented on the left panels, whereas quantification of the results by computerized confocal microscopy imaging analysis (mean+/−SEM; n=20 mice /group) is presented on the right. Empty and filled bars correspond, respectively, to ApoE3 and ApoE4 mice. Scale bar = 80 microns. (B) Lrp1 RT-PCR. Hippocampi from 4-month-old ApoE4 and ApoE3 mice were rapidly excised and snap frozen in liquid nitrogen, after which Lrp1 mRNA levels of hippocampal homogenates were determined by RT-PCR, as described in Materials and Methods. Results presented are the mean+/−SEM of 5 mice /group. Empty and filled bars correspond, respectively, to ApoE3 and ApoE4 mice.

2. The involvement of ApoE receptors in mediating the pathological synergistic interactions between ApoE4 and the amyloid cascade

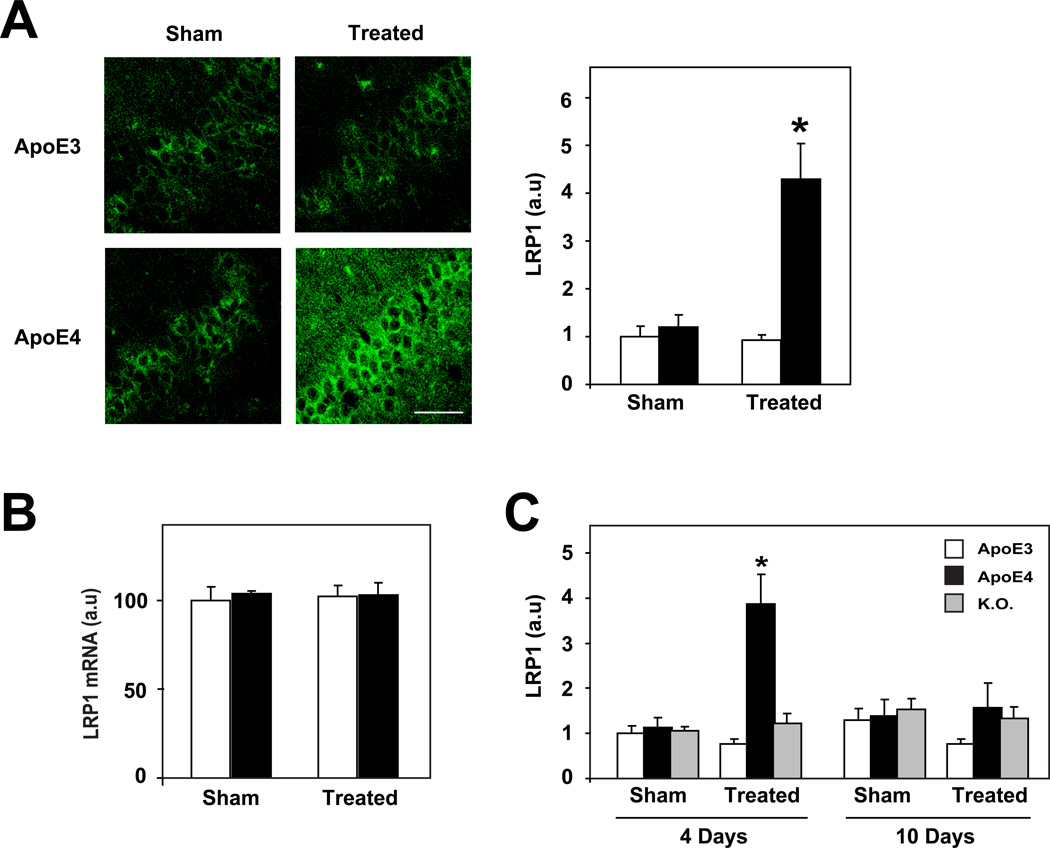

We have previously shown that elevation of Aβ by prolonged i.c.v. injection of the neprilysin inhibitor thiorphan results in the ApoE4-driven accumulation of intracellular and extracellular Aβ in the hippocampus, which is followed by synaptic and neuronal pathology and subsequent learning and memory deficits [13; 20]. We presently examined the extent to which the ApoE4-driven accumulation and oligomerization of Aβ in CA1 neurons following activation of the amyloid cascade is associated with changes in the levels of either Lrp1 or Apoer2. This treatment was performed for either 4 or 10 days, which respectively correspond to the initial phase of the response during which Aβ accumulates rapidly in CA1 neurons (4 days) and to the terminal phase (10 days) during which the ensuing neuronal and synaptic loss is maximal [13; 20]. Lrp1 immunohistochemistry of the CA1 hippocampal subfield of representative ApoE4 and ApoE3 mice, which were sham and thiorphan treated for 4 days, is depicted in figure 3A. As can be seen, the levels of Lrp1 immunostaining increased isoform-specifically only in the thiorphan-treated ApoE4. The Lrp1 staining was located in the perinuclear space of the pyramidal neurons in all mouse groups. Quantification of these results revealed that the increase in Lrp1 levels in the thiorphan-treated ApoE4 mice, in relation to all other groups analyzed, was statistically significant (P<0.001; Fig. 3A). RT-PCR measurements revealed that the mRNA levels of Lrp1 in the CA1 subfield was not affected by either the ApoE genotype or the thiorphan treatment (Fig. 3B), suggesting that the effects of ApoE4 on Lrp1 following inhibition of neprilysin are post transcriptional. Time course experiments revealed that the ApoE4-driven increase in Lrp1 is transient and that it returns back to basal levels within 10 days following the initiation of treatment (Fig. 3C). This kinetic profile precedes that of the ApoE4-driven accumulation of Aβ in CA1 neurons [20], suggesting that the rise in Lrp1 levels may play a role in the ApoE4-driven intraneuronal accumulation of Aβ, which in turn, triggers the subsequent synaptic and neuronal pathology. Additional experiments revealed that CA1 Lrp1 levels of ApoE-deficient (KO) mice, unlike those of the ApoE4 mice, were not affected by inhibition of neprilysin (Fig. 3C). This is in accordance with our previous report that the neprilysin inhibition treatment does not trigger the accumulation of Aβ in CA1 neurons of the ApoE-KO mice [49] and suggests that the ApoE4-driven accumulation of Aβ in CA1 neurons and the associated rise in Lrp1 levels are both driven via a gain of function of ApoE4.

Figure 3. The effects of activation of the amyloid cascade by inhibition of neprilysin on the levels of Lrp1 in hippocampal CA1 neurons.

4-month-old ApoE4, ApoE3 and ApoE-KO mice were injected i.c.v. utilizing Alzet mini-osmotic pumps that contained the neprilysin inhibitor thiorphan or were sham injected for 4 to 10 days, after which their brains were processed for immunohistochemistry and stained with an anti-Lrp1 Ab, as described in Materials and Methods. (A) Lrp1 immunohistochemistry in CA1 neurons of ApoE4 and ApoE3 mice 4 days following initiation of treatment. Representative sections of CA1 neurons from sham- and thiorphan-treated ApoE4 and ApoE3 mice are presented on the left panels, whereas quantification of the results by computerized confocal imaging analysis (mean+/−SEM; n=15 mice /group) is presented on the right panel. Results shown are normalized relative to those of the sham-treated ApoE3 mice whose value was set to 1. Empty and filled bars correspond, respectively, to ApoE3 and ApoE4 mice. * indicates P<0.001 for comparison of the results of the 4 mouse groups by ANOVA, followed by post-hoc analysis. Scale bar = 40 microns. (B) Lrp1 RT-PCR. The CA1 hippocampal subfields of the mice were rapidly excised and snap frozen in liquid nitrogen, after which the mRNA levels of Lrp1 were determined by RT-PCR as described in Materials and Methods. Results presented represent the mean+/−SEM of 4–6 mice /group. (C) Time course of the levels of Lrp1 in CA1 neurons of ApoE3, ApoE4 and ApoE-KO mice. Results shown were obtained by computerized analysis of the CA1 subfield of the indicated mouse groups at 4 and 10 days following initiation of treatment and are presented relative to the value of the sham-treated ApoE3 mice on day 4. Empty, black and gray-filled bars correspond, respectively, to ApoE3 and ApoE4 and ApoE-KO mice. * indicates P<0.001 for comparison of the thiorphan-treated ApoE4 mice at 4 days relative to the corresponding ApoE3 and ApoE-KO mice.

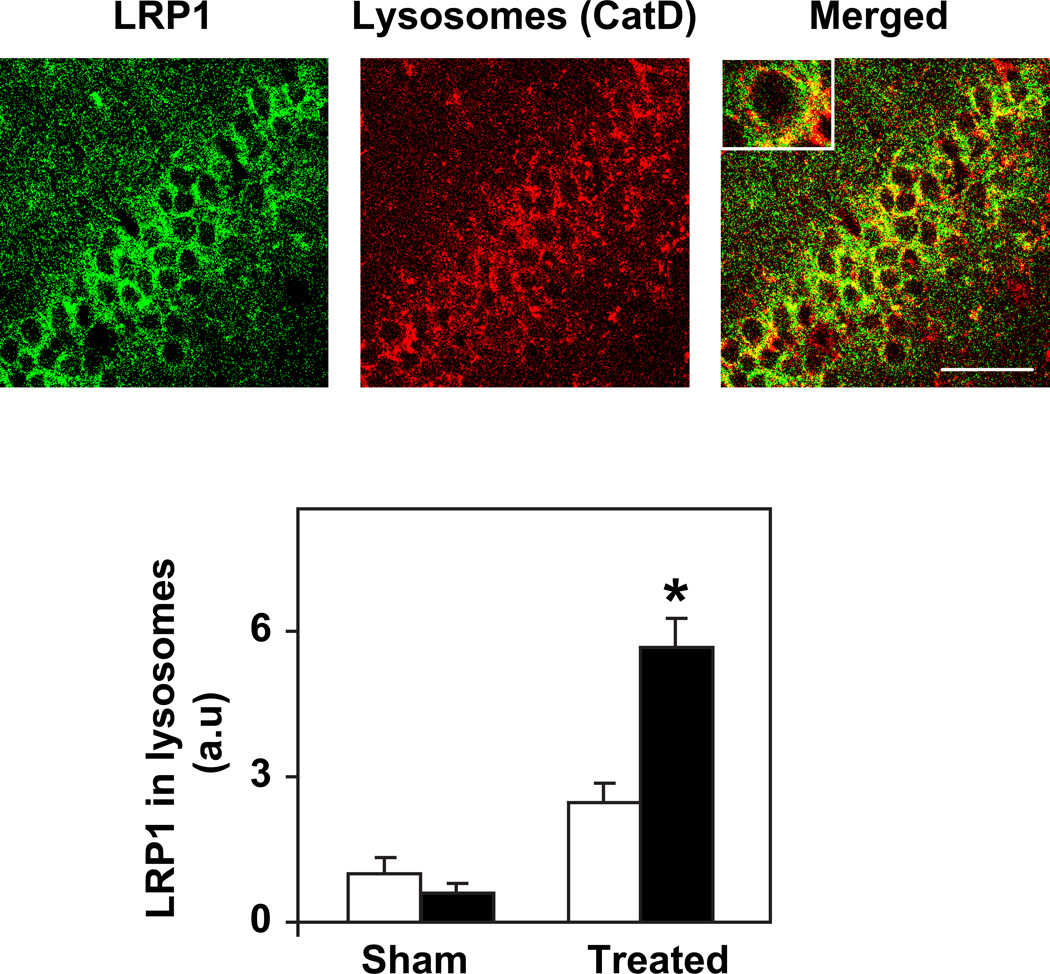

Examination of the intracellular location of Lrp1 in CA1 neurons of the different mouse groups revealed that Lrp1 co-localized with activated lysosomes following inhibition of neprilysin and that this effect is significantly larger in the ApoE4 than in the corresponding ApoE3 mice (Fig. 4; P<0.005). This is in accordance with our previous observation that inhibition of neprilysin results in the specific accumulation of Aβ and oligomerized Aβ in activated lysosomes in CA1 hippocampal neurons of the ApoE4 mice and suggests that Lrp1 may play a role in mediating the accumulation of Aβ in CA1 neurons and the associated lysosomal activations.

Figure 4. Lrp1 co-localizes with activated lysosomes in CA1 neurons of ApoE4 mice following activation of the amyloid cascade by inhibition of neprilysin.

4-month-old ApoE4 and ApoE3 mice were injected i.c.v. utilizing Alzet mini-osmotic pumps that contained the neprilysin inhibitor thiorphan or were sham injected for 4 days, after which their brains were processed for immunohistochemistry and co-stained with anti-Lrp1 and anti-cathepsin D (CatD), as described in Materials and Methods. Representative images of the CA1 area stained for Lrp1 and lysosomes (CatD) and their merged image of thiorphan-treated ApoE4 mice are depicted on the top. Insert depicts a selected neuron at ×3 magnification. Quantification of the extent of co-localization of Lrp1 and the lysosomes in the sham- and thiorphan-treated ApoE4 and ApoE3 mice was performed by computerized confocal image analysis, as described in Materials and Methods. The results (mean +/− SEM, n=4–6 mice /group) are depicted on the bottom and are presented relative to the area of Lrp1 and CatD co-staining of the sham-treated ApoE3 mice. * indicates P<0.005. Scale bar = 40 microns.

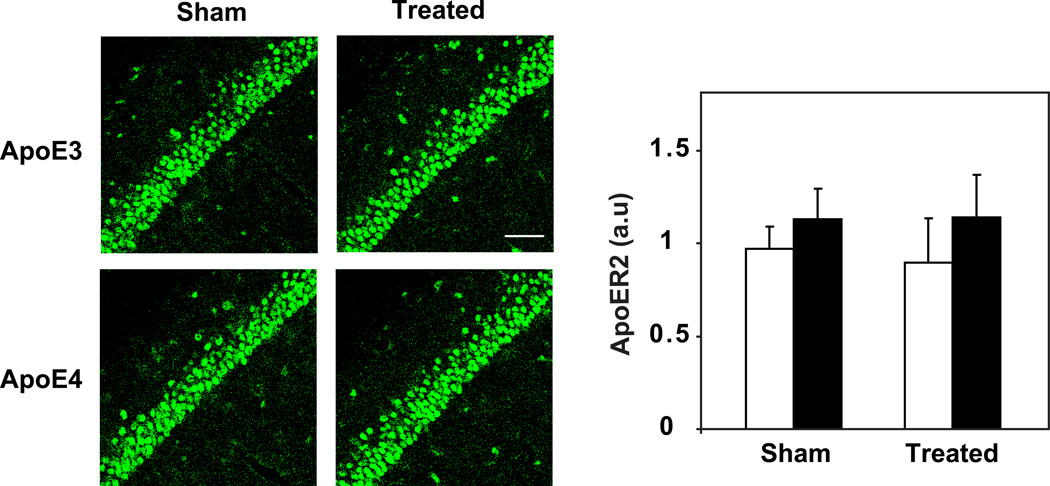

Measuring the levels of Apoer2 in CA1 neurons, following inhibition of neprilysin, revealed that, unlike Lrp1, they were the same in the sham- and thiorphan-treated ApoE4 and ApoE3 mice at both 4 days (Fig. 5) and 10 days (data not shown) following the initiation of the treatment. Note that whereas the Apoer2 levels in CA1 neurons in the sham-treated mice are the same, they are lower in naïve ApoE4 mice than in the corresponding ApoE3 mice (compare Fig. 1 and Fig. 5), suggesting that the sham treatment by itself affects the levels of Apoer2, which may mask the effect of the neprilysin inhibition treatment on the levels of Apoer2.

Figure 5. The levels of Apoer2 in thiorphan- and sham-treated ApoE4 and ApoE3 mice.

4-month-old ApoE4 ApoE3 mice were injected i.c.v. utilizing Alzet mini-osmotic pumps that contained the neprilysin inhibitor thiorphan or sham-injected for 4 days, after which their brains were processed for immunohistochemistry and stained with anti-Apoer2 Ab, as described in Materials and Methods. Representative sections of CA1 neurons of sham- and thiorphan-treated ApoE4 and ApoE3 mice are presented in panels on the left. Scale bar = 80 microns. Quantification of the results by computerized confocal imaging analysis (mean+/− SEM; n=15 mice /group) is presented on the right panel. Results shown are normalized relative to those of the sham-treated ApoE3 mice whose value was set to 1.

Discussion

This study investigated the possible role of the ApoE receptors Lrp1 and Apoer2 in mediating the pathological effects of ApoE4 in vivo. Immunohistochemical experiments revealed that the ApoE4-driven accumulation of Aβ in CA1 hippocampal neurons following inhibition of the Aβ-degrading enzyme neprilysin is associated with the up-regulation of Lrp1 in these neurons but that no changes occurred in the levels of the corresponding Apoer2 receptor. These effects were mediated via a gain of function mechanism as they were not observed in the ApoE-KO mice, whose CA1 Aβ and Lrp1 levels were similar to those of the corresponding ApoE3 mice. The ApoE receptors of young naive ApoE4 mice were also affected differentially and isoform specifically by ApoE4. However, under these conditions the effect was an ApoE4-driven reduction in Apoer2 levels in CA1 and CA3 pyramidal neurons, whereas the levels of Lrp1 were not affected. A summary of these results is presented in Table 1. RT-PCR measurements revealed that the mRNA levels of Lrp1 and Apoer2 in the hippocampus of naïve and neprilysin-inhibited mice were not affected by ApoE4, suggesting that the observed effects of ApoE4 on the levels of these receptors is post-transcriptional. The ApoE4-related post-transcriptional regulation could be either of the level of the translation of the mRNA or of the life cycle of the proteins themselves. Previous studies have shown that ApoE4 effects the internalization of proteins, such as Apoer2 [42], suggesting a possible mechanism for the post-transcriptional ApoE4 effect on the levels of the ApoE receptors. Next, we will discuss mechanisms by which ApoE4 can regulate the levels of Lrp1 and Apoer2 and the possible role of these receptors in mediating the pathological effects of ApoE4.

Table 1.

Summary of the effects of ApoE4 on the levels of Lrp1 and Apoer2 in the naïve mice model and the neprilysin inhibition paradigm.

| Model | Naïve ApoE4 mice | Neprilysin inhibition in ApoE4 mice |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Receptors | CA1 | CA3 | DG | CA1 |

| Apoer2 (% ApoE3) |

59±6 (p<0.005) |

31±5 (p<0.0001) |

104±4 (N.S.) |

114±23 (N.S.) |

| Lrp1 (% ApoE3) |

88±13 (N.S.) |

85±10 (N.S.) |

109±11 (N.S.) |

430±74 (p<0.001) |

N.S. = Not Significant

Lrp1

The finding that the Lrp1 receptor localizes within activated lysosomes (as indicated by the Lrp1 and CatD co-immunostaining) of CA1 neurons following activation of the amyloid cascade (Fig. 4), and that this effect is associated with the concurrent accumulation of Aβ, Aβ oligomers and ApoE4 in this intracellular organelle [20], suggests that the trapping of these molecules in the lysosomes and the resulting lysosomal pathology may trigger subsequent synaptic and neuronal loss [13]. This possibility is supported by previous in vitro studies that showed that ApoE3 promotes lysosomal trafficking of Aβ more efficiently than ApoE4 in a neuronal N2a cell line [50–52] and that Lrp1 complexes with both Aβ and ApoE [43; 53; 54]. The observed ApoE4-driven elevation in Lrp1 levels may be due to a compensatory response, following their trapping in the lysosomes, which is directed at restoring the functionality of the Lrp1 receptors. Alternatively, since Lrp1 can bind Aβ either directly or via ApoE [55–60], it is therefore also possible that the ApoE4-driven increase in Lrp1 is mediated by direct molecular interactions between these molecules. Although the detailed mechanism remains to be determined, the findings that the levels of Lrp1 and Aβ in CA1 neurons of ApoE-KO mice are not affected by the inhibition of neprilysin and are similar to those of the corresponding ApoE3 mice (see Fig. 3), suggest that the ApoE4-driven elevation in the levels of Lrp1 is driven by a gain of function mechanism.

There is a large body of evidence suggesting that Lrp1 can facilitate the accumulation of Aβ in numerous cells including neurons, astrocytes, and microglia [53; 57; 61–63]. The finding that the ApoE4-driven increase in Lrp1 peaks before the accumulation of Aβ [20] is consistent with the possibility that the accumulation of Aβ in CA1 neurons is mediated via the ApoE4-driven accumulation of Lrp1 (Fig. 3C). The mechanisms by which ApoE4 and the inhibition of neprilysin trigger the production of Lrp1 but not of Apoer2 are not known. It is possible that the initial elevation in Aβ levels triggers a response directed at its removal for which Lrp1, as a transport endocytotic receptor, is more suitable than Apoer2, which is known more for its function as a signaling receptor [41; 64]. The finding that in naïve mice Lrp1 is not affected by ApoE4 is consistent with this interpretation since the trigger for this effect in the neprilysin inhibition paradigm, namely, elevated Aβ levels, is not present in naïve mice. Lrp1 can stimulate the accumulation of cellular Aβ either by facilitating the uptake of extracellular Aβ or by interacting directly with APP and modulating its trafficking and intracellular processing to Aβ [17; 31; 63; 65–68]. Since Neprilysin is both intra- and extracellular [69], both mechanisms could play a role in neprilysin-inhibited ApoE4 mice.

Apoer2

Recent studies show that ApoE4 interferes with the endocytotic recycling pathway by sequestering Apoer2 in intracellular compartments and impairing its ability to recycle back to the cell membrane [42]. Accordingly, it is possible that ApoE4 stimulates the intracellular trapping of Apoer2 following endocytosis and consequently leads to its degradation [70; 71]. The finding that ApoE4 reduces the levels of Apoer2 in young naïve mice, but not following inhibition of neprilysin, is most interesting. Lrp1 exhibits a fast rate of endocytosis [65; 72] compared to Apoer2 [53; 72; 73]. Accordingly, it is possible that under overload conditions, such as inhibition of neprilysin, the lysosomes are saturated by Lrp1. This in turn prevents the endocytosis of Apoer2 and thereby protects it from the deleterious effects of ApoE4. In contrast, under milder non-saturating conditions, such as young naive ApoE4 mice in which the Lrp1 system is not up-regulated, Apoer2 can undergo endocytosis and is thus affected by ApoE4. Note that in naïve mice the level of Apoer2 is lower in ApoE4 mice, whereas in the sham-treated mice, the levels are similar. The observed effects of sham treatment on the levels of Apoer2 may be due to the inflammatory effects of the implantation of the cannula into the brain [74; 75].

Apoer2 is known to play important roles both in the development and function of the nerve system [76]. In particular, it has been shown that Apoer2 affects synaptic plasticity and function [77; 78] and that it affects tau hyperphosphorylation [37; 79] as well as APP and Aβ metabolism [53]. We have recently shown that young (4-month-old) naive ApoE4 mice are cognitively impaired and that their learning and memory impairments are associated with synaptic impairments, accumulation of Aβ and hyperphosphorylated tau in hippocampal neurons [24]. The extent to which these pathological phenotypes of ApoE4 are driven by reduced Apoer2 levels and are related to development processes are currently being investigated.

In conclusion, this study shows that the levels of the hippocampal ApoE receptors Lrp1 and Apoer2 are affected isoform specifically by ApoE4 and that the type of receptor affected and the associated pathophysiological consequences are context dependent. Accordingly, Lrp1 plays a role under certain circumstances, such as activation of the amyloid cascade by inhibition of neprilysin, in which the Aβ cascade is strongly activated, whereas Apoer2 plays a role under milder, not necessarily Aβ-related conditions. These findings have important implications regarding the design of ApoE receptor-targeted therapy.

Acknowledgments

We thank Alex Nakaryakov for his technical assistance and for maintaining the mouse colonies. This work was supported in part by grants from the LIPIDIDIET grant funded by the 7th Framework Program of the European Union, the Joseph K. and Inez Eichenbaum Foundation, the Diane Pregerson Glazer and Guilford Glazer Foundation, and Harold and Eleanore Foonberg. DMM is the incumbent of the Myriam Lebach Chair in Molecular Neurodegeneration.

Footnotes

Conflict of interests

The authors declare they have no conflict of interests.

Author's contribution:

MGF Designed and performed research, collected and analyzed data, wrote paper.

ABC Performed research, analyzed data, wrote paper.

OL Performed research, analyzed data, wrote paper.

XX Prepared the antibodies

JH Analyzed data, wrote paper

DMM Designed research, wrote paper

References

- 1.Masters CL, Simms G, Weinman NA, Multhaup G, McDonald BL, Beyreuther K. Amyloid plaque core protein in Alzheimer disease and Down syndrome. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1985;82(12):4245–4249. doi: 10.1073/pnas.82.12.4245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Corder EH, Saunders AM, Strittmatter WJ, Schmechel DE, Gaskell PC, Small GW, et al. Gene dose of apolipoprotein E type 4 allele and the risk of Alzheimer's disease in late onset families. Science (New York, NY. 1993;261(5123):921–923. doi: 10.1126/science.8346443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Roses AD. Apolipoprotein E alleles as risk factors in Alzheimer's disease. Annual review of medicine. 1996;47:387–400. doi: 10.1146/annurev.med.47.1.387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Saunders AM, Strittmatter WJ, Schmechel D, George-Hyslop PH, Pericak-Vance MA, Joo SH, et al. Association of apolipoprotein E allele epsilon 4 with late-onset familial and sporadic Alzheimer's disease. Neurology. 1993;43(8):1467–1472. doi: 10.1212/wnl.43.8.1467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Liang WS, Reiman EM, Valla J, Dunckley T, Beach TG, Grover A, et al. Alzheimer's disease is associated with reduced expression of energy metabolism genes in posterior cingulate neurons. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2008;105(11):4441–4446. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0709259105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Reiman EM, Chen K, Liu X, Bandy D, Yu M, Lee W, et al. Fibrillar amyloid-beta burden in cognitively normal people at 3 levels of genetic risk for Alzheimer's disease. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106(16):6820–6825. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0900345106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Heise V, Filippini N, Ebmeier KP, Mackay CE. The APOE varepsilon4 allele modulates brain white matter integrity in healthy adults. Molecular psychiatry. 2010;16(9):908–916. doi: 10.1038/mp.2010.90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mori E, Lee K, Yasuda M, Hashimoto M, Kazui H, Hirono N, et al. Accelerated hippocampal atrophy in Alzheimer's disease with apolipoprotein E epsilon4 allele. Annals of neurology. 2002;51(2):209–214. doi: 10.1002/ana.10093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Schmechel DE, Saunders AM, Strittmatter WJ, Crain BJ, Hulette CM, Joo SH, et al. Increased amyloid beta-peptide deposition in cerebral cortex as a consequence of apolipoprotein E genotype in late-onset Alzheimer disease. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 1993;90(20):9649–9653. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.20.9649. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Arendt T, Schindler C, Bruckner MK, Eschrich K, Bigl V, Zedlick D, et al. Plastic neuronal remodeling is impaired in patients with Alzheimer's disease carrying apolipoprotein epsilon 4 allele. J Neurosci. 1997;17(2):516–529. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.17-02-00516.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Egensperger R, Kosel S, von Eitzen U, Graeber MB. Microglial activation in Alzheimer disease: Association with APOE genotype. Brain Pathol. 1998;8(3):439–447. doi: 10.1111/j.1750-3639.1998.tb00166.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Inbar D, Belinson H, Rosenman H, Michaelson DM. Possible role of tau in mediating pathological effects of apoE4 in vivo prior to and following activation of the amyloid cascade. Neuro-degenerative diseases. 2010;7(1–3):16–23. doi: 10.1159/000283477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Belinson H, Lev D, Masliah E, Michaelson DM. Activation of the amyloid cascade in apolipoprotein E4 transgenic mice induces lysosomal activation and neurodegeneration resulting in marked cognitive deficits. J Neurosci. 2008;28(18):4690–4701. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5633-07.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Belinson H, Michaelson DM. ApoE4-dependent Abeta-mediated neurodegeneration is associated with inflammatory activation in the hippocampus but not the septum. J Neural Transm. 2009;116(11):1427–1434. doi: 10.1007/s00702-009-0218-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hartman RE, Wozniak DF, Nardi A, Olney JW, Sartorius L, Holtzman DM. Behavioral phenotyping of GFAP-apoE3 and -apoE4 transgenic mice: apoE4 mice show profound working memory impairments in the absence of Alzheimer's-like neuropathology. Exp Neurol. 2001;170(2):326–344. doi: 10.1006/exnr.2001.7715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Manelli AM, Bulfinch LC, Sullivan PM, LaDu MJ. Abeta42 neurotoxicity in primary co-cultures: effect of apoE isoform and Abeta conformation. Neurobiol Aging. 2007;28(8):1139–1147. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2006.05.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ye S, Huang Y, Mullendorff K, Dong L, Giedt G, Meng EC, et al. Apolipoprotein (apo) E4 enhances amyloid beta peptide production in cultured neuronal cells: apoE structure as a potential therapeutic target. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2005;102(51):18700–18705. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0508693102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Holtzman DM. In vivo effects of ApoE and clusterin on amyloid-beta metabolism and neuropathology. J Mol Neurosci. 2004;23(3):247–254. doi: 10.1385/JMN:23:3:247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Selkoe DJ. Alzheimer's disease: genes, proteins, and therapy. Physiol Rev. 2001;81(2):741–766. doi: 10.1152/physrev.2001.81.2.741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Belinson H, Kariv-Inbal Z, Kayed R, Masliah E, Michaelson DM. Following activation of the amyloid cascade, apolipoprotein E4 drives the in vivo oligomerization of amyloid-beta resulting in neurodegeneration. J Alzheimers Dis. 2010;22(3):959–970. doi: 10.3233/JAD-2010-101008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nathan BP, Bellosta S, Sanan DA, Weisgraber KH, Mahley RW, Pitas RE. Differential effects of apolipoproteins E3 and E4 on neuronal growth in vitro. Science (New York, NY. 1994;264(5160):850–852. doi: 10.1126/science.8171342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kariv-Inbal Z, Yacobson S, Berkecz R, Peter M, Janaky T, Lutjohann D, et al. The isoform-specific pathological effects of apoE4 in vivo are prevented by a fish oil (DHA) diet and are modified by cholesterol. J Alzheimers Dis. 2012;28(3):667–683. doi: 10.3233/JAD-2011-111265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mahley RW, Huang Y. Apolipoprotein e sets the stage: response to injury triggers neuropathology. Neuron. 2012;76(5):871–885. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2012.11.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Liraz O, Boehm-Cagan A, Michaelson DM. ApoE4 induces Abeta42, tau, and neuronal pathology in the hippocampus of young targeted replacement apoE4 mice. Mol Neurodegener. 2013;8:16. doi: 10.1186/1750-1326-8-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sabo T, Lomnitski L, Nyska A, Beni S, Maronpot RR, Shohami E, et al. Susceptibility of transgenic mice expressing human apolipoprotein E to closed head injury: the allele E3 is neuroprotective whereas E4 increases fatalities. Neuroscience. 2000;101(4):879–884. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(00)00438-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Herz J. The LDL receptor gene family: (un)expected signal transducers in the brain. Neuron. 2001;29(3):571–581. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(01)00234-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bu G. Apolipoprotein E and its receptors in Alzheimer's disease: pathways, pathogenesis and therapy. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2009;10(5):333–344. doi: 10.1038/nrn2620. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bu G, Maksymovitch EA, Nerbonne JM, Schwartz AL. Expression and function of the low density lipoprotein receptor-related protein (LRP) in mammalian central neurons. The Journal of biological chemistry. 1994;269(28):18521–18528. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hayashi H, Campenot RB, Vance DE, Vance JE. Apolipoprotein E-containing lipoproteins protect neurons from apoptosis via a signaling pathway involving low-density lipoprotein receptor-related protein-1. J Neurosci. 2007;27(8):1933–1941. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5471-06.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Qiu Z, Crutcher KA, Hyman BT, Rebeck GW. ApoE isoforms affect neuronal Nmethyl-D-aspartate calcium responses and toxicity via receptor-mediated processes. Neuroscience. 2003;122(2):291–303. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2003.08.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bu G, Cam J, Zerbinatti C. LRP in amyloid-beta production and metabolism. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. 2006;1086:35–53. doi: 10.1196/annals.1377.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ruiz J, Kouiavskaia D, Migliorini M, Robinson S, Saenko EL, Gorlatova N, et al. The apoE isoform binding properties of the VLDL receptor reveal marked differences from LRP and the LDL receptor. J Lipid Res. 2005;46(8):1721–1731. doi: 10.1194/jlr.M500114-JLR200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Owen JB, Sultana R, Aluise CD, Erickson MA, Price TO, Bu G, et al. Oxidative modification to LDL receptor-related protein 1 in hippocampus from subjects with Alzheimer disease: implications for Abeta accumulation in AD brain. Free Radic Biol Med. 2010;49(11):1798–1803. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2010.09.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Herz J, Clouthier DE, Hammer RE. LDL receptor-related protein internalizes and degrades uPA-PAI-1 complexes and is essential for embryo implantation. Cell. 1992;71(3):411–421. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(92)90511-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Herz J, Bock HH. Lipoprotein receptors in the nervous system. Annu Rev Biochem. 2002;71:405–434. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.71.110601.135342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Herz J, Strickland DK. LRP: a multifunctional scavenger and signaling receptor. J Clin Invest. 2001;108(6):779–784. doi: 10.1172/JCI13992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Trommsdorff M, Gotthardt M, Hiesberger T, Shelton J, Stockinger W, Nimpf J, et al. Reeler/Disabled-like disruption of neuronal migration in knockout mice lacking the VLDL receptor and ApoE receptor 2. Cell. 1999;97(6):689–701. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80782-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Niu S, Yabut O, D'Arcangelo G. The Reelin signaling pathway promotes dendritic spine development in hippocampal neurons. J Neurosci. 2008;28(41):10339–10348. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1917-08.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Beffert U, Weeber EJ, Morfini G, Ko J, Brady ST, Tsai LH, et al. Reelin and cyclin-dependent kinase 5-dependent signals cooperate in regulating neuronal migration and synaptic transmission. J Neurosci. 2004;24(8):1897–1906. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4084-03.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.D'Arcangelo G, Homayouni R, Keshvara L, Rice DS, Sheldon M, Curran T. Reelin is a ligand for lipoprotein receptors. Neuron. 1999;24(2):471–479. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80860-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Reddy SS, Connor TE, Weeber EJ, Rebeck W. Similarities and differences in structure, expression, and functions of VLDLR and ApoER2. Mol Neurodegener. 2011;6:30. doi: 10.1186/1750-1326-6-30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Chen Y, Durakoglugil MS, Xian X, Herz J. ApoE4 reduces glutamate receptor function and synaptic plasticity by selectively impairing ApoE receptor recycling. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107(26):12011–12016. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0914984107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Deane R, Sagare A, Hamm K, Parisi M, Lane S, Finn MB, et al. apoE isoform-specific disruption of amyloid beta peptide clearance from mouse brain. J Clin Invest. 2008 doi: 10.1172/JCI36663. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.He X, Cooley K, Chung CH, Dashti N, Tang J. Apolipoprotein receptor 2 and X11 alpha/beta mediate apolipoprotein E-induced endocytosis of amyloid-beta precursor protein and beta-secretase, leading to amyloid-beta production. J Neurosci. 2007;27(15):4052–4060. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3993-06.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Sullivan PM, Mezdour H, Aratani Y, Knouff C, Najib J, Reddick RL, et al. Targeted replacement of the mouse apolipoprotein E gene with the common human APOE3 allele enhances diet-induced hypercholesterolemia and atherosclerosis. The Journal of biological chemistry. 1997;272(29):17972–17980. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.29.17972. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Levi O, Jongen-Relo AL, Feldon J, Roses AD, Michaelson DM. ApoE4 impairs hippocampal plasticity isoform-specifically and blocks the environmental stimulation of synaptogenesis and memory. Neurobiol Dis. 2003;13(3):273–282. doi: 10.1016/s0969-9961(03)00045-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.May P, Rohlmann A, Bock HH, Zurhove K, Marth JD, Schomburg ED, et al. Neuronal LRP1 functionally associates with postsynaptic proteins and is required for normal motor function in mice. Mol Cell Biol. 2004;24(20):8872–8883. doi: 10.1128/MCB.24.20.8872-8883.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Beffert U, Weeber EJ, Durudas A, Qiu S, Masiulis I, Sweatt JD, et al. Modulation of synaptic plasticity and memory by Reelin involves differential splicing of the lipoprotein receptor Apoer2. Neuron. 2005;47(4):567–579. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2005.07.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Zepa L, Frenkel M, Belinson H, Kariv-Inbal Z, Kayed R, Masliah E, et al. ApoE4-Driven Accumulation of Intraneuronal Oligomerized Abeta42 following Activation of the Amyloid Cascade In Vivo Is Mediated by a Gain of Function. Int J Alzheimers Dis. 2010;2011:792070. doi: 10.4061/2011/792070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Li J, Kanekiyo T, Shinohara M, Zhang Y, LaDu MJ, Xu H, et al. Differential regulation of amyloid-beta endocytic trafficking and lysosomal degradation by apolipoprotein E isoforms. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2012;287(53):44593–44601. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112.420224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Ji ZS, Mullendorff K, Cheng IH, Miranda RD, Huang Y, Mahley RW. Reactivity of apolipoprotein E4 and amyloid beta peptide: lysosomal stability and neurodegeneration. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2006;281(5):2683–2692. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M506646200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Ji ZS, Miranda RD, Newhouse YM, Weisgraber KH, Huang Y, Mahley RW. Apolipoprotein E4 potentiates amyloid beta peptide-induced lysosomal leakage and apoptosis in neuronal cells. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2002;277(24):21821–21828. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112109200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Fuentealba RA, Barria MI, Lee J, Cam J, Araya C, Escudero CA, et al. ApoER2 expression increases Abeta production while decreasing Amyloid Precursor Protein (APP) endocytosis: Possible role in the partitioning of APP into lipid rafts and in the regulation of gamma-secretase activity. Mol Neurodegener. 2007;2:14. doi: 10.1186/1750-1326-2-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Zerbinatti CV, Wahrle SE, Kim H, Cam JA, Bales K, Paul SM, et al. Apolipoprotein E and low density lipoprotein receptor-related protein facilitate intraneuronal Abeta42 accumulation in amyloid model mice. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2006;281(47):36180–36186. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M604436200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Sokolow S, Luu SH, Nandy K, Miller CA, Vinters HV, Poon WW, et al. Preferential accumulation of amyloid-beta in presynaptic glutamatergic terminals (VGluT1 and VGluT2) in Alzheimer's disease cortex. Neurobiol Dis. 2012;45(1):381–387. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2011.08.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Deane R, Wu Z, Sagare A, Davis J, Du Yan S, Hamm K, et al. LRP/amyloid beta-peptide interaction mediates differential brain efflux of Abeta isoforms. Neuron. 2004;43(3):333–344. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2004.07.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Verghese PB, Castellano JM, Garai K, Wang Y, Jiang H, Shah A, et al. ApoE influences amyloid-beta (Abeta) clearance despite minimal apoE/Abeta association in physiological conditions. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2013 doi: 10.1073/pnas.1220484110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Kim J, Basak JM, Holtzman DM. The role of apolipoprotein E in Alzheimer's disease. Neuron. 2009;63(3):287–303. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2009.06.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.LaDu MJ, Falduto MT, Manelli AM, Reardon CA, Getz GS, Frail DE. Isoform-specific binding of apolipoprotein E to beta-amyloid. The Journal of biological chemistry. 1994;269(38):23403–23406. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Sagare AP, Bell RD, Srivastava A, Sengillo JD, Singh I, Nishida Y, et al. A lipoprotein receptor cluster IV mutant preferentially binds amyloid-beta and regulates its clearance from the mouse brain. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2013 doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112.439570. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Kanekiyo T, Zhang J, Liu Q, Liu CC, Zhang L, Bu G. Heparan sulphate proteoglycan and the low-density lipoprotein receptor-related protein 1 constitute major pathways for neuronal amyloid-beta uptake. J Neurosci. 2011;31(5):1644–1651. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5491-10.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Zerbinatti CV, Wozniak DF, Cirrito J, Cam JA, Osaka H, Bales KR, et al. Increased soluble amyloid-beta peptide and memory deficits in amyloid model mice overexpressing the low-density lipoprotein receptor-related protein. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101(4):1075–1080. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0305803101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Ulery PG, Beers J, Mikhailenko I, Tanzi RE, Rebeck GW, Hyman BT, et al. Modulation of beta-amyloid precursor protein processing by the low density lipoprotein receptor-related protein (LRP). Evidence that LRP contributes to the pathogenesis of Alzheimer's disease. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2000;275(10):7410–7415. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.10.7410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.May P, Herz J, Bock HH. Molecular mechanisms of lipoprotein receptor signalling. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2005;62(19–20):2325–2338. doi: 10.1007/s00018-005-5231-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Cam JA, Zerbinatti CV, Li Y, Bu G. Rapid endocytosis of the low density lipoprotein receptor-related protein modulates cell surface distribution and processing of the beta-amyloid precursor protein. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2005;280(15):15464–15470. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M500613200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Marzolo MP, Bu G. Lipoprotein receptors and cholesterol in APP trafficking and proteolytic processing, implications for Alzheimer's disease. Semin Cell Dev Biol. 2009;20(2):191–200. doi: 10.1016/j.semcdb.2008.10.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Tamaki C, Ohtsuki S, Terasaki T. Insulin facilitates the hepatic clearance of plasma amyloid beta-peptide (1 40) by intracellular translocation of low-density lipoprotein receptor-related protein 1 (LRP-1) to the plasma membrane in hepatocytes. Mol Pharmacol. 2007;72(4):850–855. doi: 10.1124/mol.107.036913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Clifford PM, Zarrabi S, Siu G, Kinsler KJ, Kosciuk MC, Venkataraman V, et al. Abeta peptides can enter the brain through a defective blood-brain barrier and bind selectively to neurons. Brain Res. 2007;1142:223–236. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2007.01.070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Kakiya N, Saito T, Nilsson P, Matsuba Y, Tsubuki S, Takei N, et al. Cell surface expression of the major amyloid-beta peptide (Abeta)-degrading enzyme, neprilysin, depends on phosphorylation by mitogen-activated protein kinase/extracellular signal-regulated kinase kinase (MEK) and dephosphorylation by protein phosphatase 1a. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2012;287(35):29362–29372. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112.340372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Poirier S, Mayer G, Benjannet S, Bergeron E, Marcinkiewicz J, Nassoury N, et al. The proprotein convertase PCSK9 induces the degradation of low density lipoprotein receptor (LDLR) and its closest family members VLDLR and ApoER2. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2008;283(4):2363–2372. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M708098200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Yamamoto T, Lu C, Ryan RO. A two-step binding model of PCSK9 interaction with the low density lipoprotein receptor. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2011;286(7):5464–5470. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.199042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Li Y, Marzolo MP, van Kerkhof P, Strous GJ, Bu G. The YXXL motif, but not the two NPXY motifs, serves as the dominant endocytosis signal for low density lipoprotein receptor-related protein. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2000;275(22):17187–17194. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M000490200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Li Y, Lu W, Marzolo MP, Bu G. Differential functions of members of the low density lipoprotein receptor family suggested by their distinct endocytosis rates. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2001;276(21):18000–18006. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M101589200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Norman PE, House AK. Heparin reduces the intimal hyperplasia seen in microvascular vein grafts. The Australian and New Zealand journal of surgery. 1991;61(12):942–948. doi: 10.1111/j.1445-2197.1991.tb00013.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Gomez-Sanchez EP, Gomez-Sanchez CE. Maternal hypertension and progeny blood pressure: role of aldosterone and 11beta-HSD. Hypertension. 1999;33(6):1369–1373. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.33.6.1369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Cheng L, Tian Z, Sun R, Wang Z, Shen J, Shan Z, et al. ApoER2 and VLDLR in the developing human telencephalon. European journal of paediatric neurology : EJPN : official journal of the European Paediatric Neurology Society. 2011;15(4):361–367. doi: 10.1016/j.ejpn.2011.03.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Qiu S, Zhao LF, Korwek KM, Weeber EJ. Differential reelin-induced enhancement of NMDA and AMPA receptor activity in the adult hippocampus. J Neurosci. 2006;26(50):12943–12955. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2561-06.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Qiu S, Weeber EJ. Reelin signaling facilitates maturation of CA1 glutamatergic synapses. Journal of neurophysiology. 2007;97(3):2312–2321. doi: 10.1152/jn.00869.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Brich J, Shie FS, Howell BW, Li R, Tus K, Wakeland EK, et al. Genetic modulation of tau phosphorylation in the mouse. J Neurosci. 2003;23(1):187–192. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-01-00187.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]