Abstract

The activity of smooth and non-muscle myosin II is regulated by phosphorylation of the regulatory light chain (RLC) at serine 19. The dephosphorylated state of full-length monomeric myosin is characterized by an asymmetric intramolecular head-head interaction that completely inhibits the ATPase activity, accompanied by a hairpin fold of the tail, which prevents filament assembly. Phosphorylation of serine 19 disrupts these head-head interactions by an unknown mechanism. Computational modeling suggested that formation of the inhibited state is characterized by both torsional and bending motions about the myosin heavy chain (HC) at a location between the RLC and the essential light chain (ELC). Therefore, altering relative motions between the ELC and the RLC at this locus might disrupt the inhibited state. Based on this hypothesis we have derived an atomic model for the phosphorylated state of the smooth muscle myosin light chain domain (LCD). This model predicts a set of specific interactions between the N-terminal residues of the RLC with both the myosin HC and the ELC. Site directed mutagenesis was used to show that interactions between the phosphorylated N-terminus of the RLC and helix-A of the ELC are required for phosphorylation to activate smooth muscle myosin.

Keywords: modeling, motility, ATPase, phosphorylation

INTRODUCTION

Phosphorylation of the regulatory light chain (RLC) of smooth muscle and non-muscle myosin affects two major properties of these class II myosins: it enhances the actin-activated ATPase activity (Sellers, 1985), and it affects the solubility of myosin by favoring filament formation (Trybus, 1991). Biochemical studies have shown that the inhibited state requires two myosin heads, because single-headed species are constitutively active (Cremo et al., 1995; Sweeney et al., 2000). Dephosphorylation reduces the actin-activated ATPase activity of smooth muscle heavy meromyosin (smHMM) by more than 25-fold, while only slightly reducing actin binding (Sellers et al., 1982), suggesting that ATPase inhibition primarily affects product release.

Much of the biochemistry can be explained by an asymmetric, intramolecular interaction between the two-myosin heads, first visualized by cryoelectron microscopy (cryoEM) of 2-D arrays of dephosphorylated smHMM (Wendt et al., 2001). Subsequently, this motif was also identified in thick filaments from three striated muscles (Woodhead et al., 2005; Zhao et al., 2009; Zoghbi et al., 2008), as well as in electron micrographs of negatively stained single molecules of myosin II isoforms from several species (Burgess et al., 2007; Jung et al., 2008a). The near ubiquitous presence of this intramolecular myosin head-head interaction has led to the suggestion that it is both an ancient and general mechanism for myosin II inhibition (Jung et al., 2008a; Jung et al., 2008b).

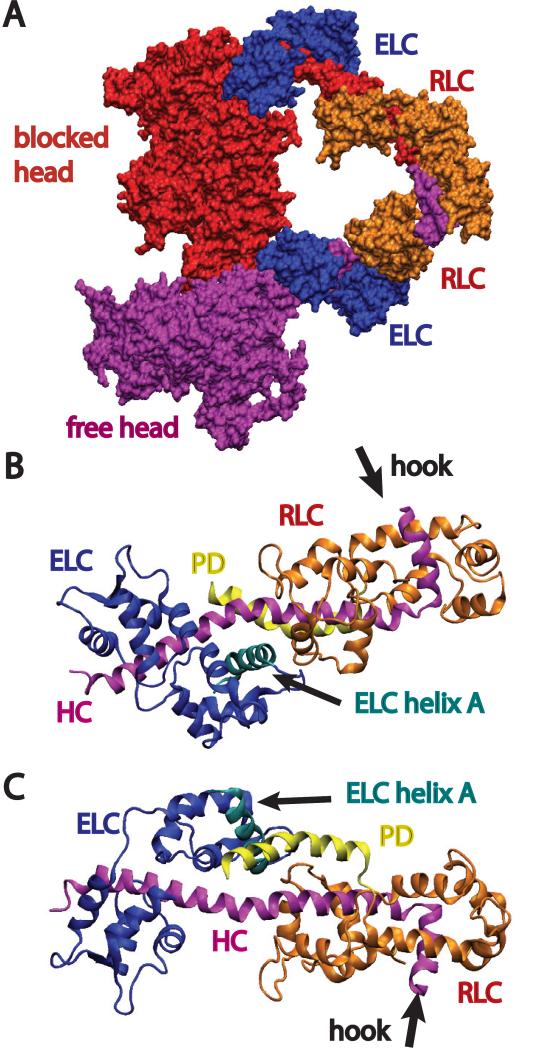

In the dephosphorylated state (Fig. 1A), the upper 50 kDa domain of one myosin head (“blocked” head) is juxtaposed with the upper 50 kDa domain, converter domain and essential light chain (ELC) of the other head (“free” head). In this conformation, the “blocked” head can not be docked onto actin without a steric clash with the “free” head. Conversely, the “free” head can be docked onto actin without steric interference from the “blocked” head, thereby explaining the retention of actin binding in the inhibited state (Sellers et al., 1982). This head-head interaction provided a convincing mechanism for stabilizing motions within the myosin heads that are required for phosphate release.

Figure 1. Background on smooth muscle myosin regulation.

Color scheme used throughout except where specifically noted has the free head heavy chain (HC) - magenta, the blocked head – red, ELC – blue, RLC – orange with the 24-residue phosphorylation domain (PD) colored yellow. Helix-A of the ELC is colored cyan. (A) In the inhibited conformation the blocked head motor domain (MD) binds the free head MD at a position consisting of parts of the converter domain, MD and ELC. In this position the free head sterically inhibits actin binding by the blocked head, but actin binding by the free head is not similarly affected. The myosin S2 domain would be positioned on the near side of the molecule and lies over the MD of the blocked head. (B) Atomic model of the LCD rendered in a ribbon diagram with the PD position as obtained in the present study. The LCD is oriented similar to that of the free head shown in (A). Within the LCD (on the right), the HC makes a nearly 90° bend to form the “hook” which connects the myosin head to the coiled-coil S2 domain. (C) View of the LCD after rotating about the horizontal axis by ~180°. All graphics produced using VMD (Humphrey et al., 1996).

The normally extended α-helical coiled-coil rod in dephosphorylated smooth and non-muscle myosin II isoforms bends in the presence of MgATP and low ionic strength to assume a folded hairpin monomeric conformation which sediments at 10S (Svedberg) (Craig et al., 1983; Trybus et al., 1982), and effectively inhibits product release (Cross et al., 1986). Addition of salt unfolds 10S myosin back to the typical 6S structure. In the 10S conformation, smooth muscle myosin heads are engaged in an intramolecular interaction virtually identical to that found in smHMM (Burgess et al., 2007; Liu et al., 2003). Salt-dependent conformational changes (from 9S to 7S) reflecting changes in head disposition are also observed with smHMM (Nag et al., 1987; Suzuki et al., 1985). Thus, ATPase inhibition and myosin solubility were shown to be dependent on the same head-head interaction, but how they are linked and the consequences of this on the physiology of smooth muscle are less clear.

The first 24 residues that comprise the N-terminus of the RLC have been dubbed the phosphorylation domain (PD), terminology that distinguishes these residues from the portion of the N-terminal domain that is visible in myosin crystal structures (Espinoza-Fonseca et al., 2008). Phosphorylation of the PD at S19 disrupts the head-head interaction of the inhibited state producing a conformation with the heads extended away from each other on opposite sides of the elongated coiled-coil rod (Craig et al., 1983; Trybus et al., 1982), a structure which is competent for filament assembly at physiological ionic strength. Recently, a structural analysis of phosphorylated smHMM by cryoEM showed an open conformation with heads disposed on opposite sides of the rod subfragment-2 (S2), but the interaction between heads from different molecules was similar to that observed in dephosphorylated smHMM (Baumann et al., 2012). This suggests that phosphorylation has a minimal effect on the motor domain (MD-MD) interfaces themselves, and mostly affects the ability to form a stable intramolecular interaction.

The PD is located distant from the site of the head-head interaction (Fig. 1B) and its structure and interacting partners in the phosphorylated state have not been determined. Despite a large number of studies probing the effect of phosphorylation on smooth muscle myosin regulation, no structural model has yet emerged that unifies the experimental observations. A recent modeling study that applied normal mode analysis to the conformational change from a putative “active” state to the folded inhibited state, found that head motions required to achieve the intramolecular head-head interaction can propagate distortions throughout the S2 and LMM regions (Tama et al., 2005). The coupled motion between the coiled-coil rod and myosin heads may explain some puzzling features of myosin and motor function, among them the effect of S2 length on regulation (Trybus et al., 1997). The modeling also indicated that a key stress point in the myosin HC occurs at a location between the ELC and the RLC, dubbed the “elbow” (Ni et al., 2012). This is one locus where the X-ray structure of the scallop myosin light chain binding domain (LCD) differed from the chicken skeletal myosin LCD (Houdusse and Cohen, 1996). A more recent comparison of cryoEM structures of both dephosphorylated and phosphorylated smHMM showed that the “blocked head” was more bent at this locus than the dephosphorylated “free head”, the phosphorylated heads or even structures of isolated LCDs (Baumann et al., 2012).

These observations suggested that mechanical stress on the HC elbow resulting from the head-head interaction might be relieved by placement of the PD at this location. This report describes the resulting model (Fig. 1B, C) and its possible effects on the inhibited to active conformational change. The model makes specific predictions about interactions between amino acid residues that are needed to stabilize the PD when phosphorylated. The most significant of these interactions was tested by site directed mutagenesis. The results indicate that contrary to prior investigations, the ELC plays an important role in phosphorylation-based activation of smHMM through an interaction between the PD and helix-A of the ELC.

MATERIALS and METHODS

Sequence Alignment

Multisequence alignments were done using the GCG software package (Butler, 1998). We carried out a multisequence alignment of 73 complete myosin II HC sequences, 78 complete RLC sequences and 78 complete ELC sequences found in the various data bases, including PubMed, SwissProt, and Trembl using the GCG software package (Butler, 1998).

LCD Modeling

The atomic model for the smooth muscle myosin LCD comprised a segment consisting of myosin HC with the ELC bound to it taken from the X-ray crystal structure of the smooth muscle myosin motor domain-ELC fragment (PDB-1BR1) (Dominguez et al., 1998) and a homology model for the RLC with its bound HC. Details of the homology modeling can be found in Tama et al. (Tama et al., 2005). We built RLC homology models based on chicken skeletal myosin (PDB -2MYS) and scallop striated muscle myosin (PDB – 1WDC). These crystal structures only included residues corresponding to F25 to K167 in the smooth muscle myosin RLC. Although two RLC models were built, only the one based on 2MYS was pursued. The atomic model for the smooth muscle myosin LCD was built by aligning the RLC homology model using HC residues 793-814 then splicing the homology model onto the MD-ELC structure (Dominguez et al., 1998). All residues from the crystal structure were retained. The final model consisted of residues 788-851 of the heavy chain, residues 3-150 of the ELC and residues 1-167 of the RLC.

Modeling of the RLC N-terminus

There is little experimental information on the structure of the PD. To estimate its secondary structure, we ran its sequence through the Predict Protein server (Rost et al., 2004), which predicted two regions of helix probability greater than 50%. These included the sequences 2SKRAKAKT9 and 13RPQRAT18. This placed two key residues, K11 and K12, known to affect phosphorylation-based activation (Ikebe et al., 1994) in the connection. We therefore built most of the PD as an α-helix. Helical content for the PD in the phosphorylated state has some experimental support as well (Kast et al., 2010; Nelson et al., 2005).

We then made the assumption that the interaction between the PD and the LCD involved the myosin HC. Because the HC is α-helical and the PD was built predominately α-helical, we arranged them in an α-helical coiled-coil. To determine the orientation of the coiled-coil, we constructed models for all 7 orientations but only 2 actually could be placed on the LCD without backbone clashes with either the RLC or the ELC. The site selected for further development placed the PD on the opposite side of the HC from the closest approach between the ELC and the RLC, which corresponds to the Ca2+ binding site in the scallop myosin LCD (Houdusse and Cohen, 1996). The other chain of the hypothesized coiled-coil consisted of residues 811-819 on the myosin HC.

The propensity for forming a coiled-coil between the HC and the RLC N-terminus is very poor because there are few hydrophobic residues in either chain that are usefully placed. In addition, both regions are positively charged. The only acidic groups in the region are to be found on helix-A at the ELC N-terminus. The virtue in building this interaction as if it were a coiled-coil lies in its simplicity and ease of construction due to the well-defined placement of the two α-helices.

We then tested various rotational orientations of the PD within the coiled-coil structure constraint and visually examined opportunities for salt bridge formation between the RLC, ELC or HC. The model with the most salt bridges placed the phosphorylated serine near K823 and R827 of the HC and RLC residue R16. RLC residues R13 and K12 were near ELC residue E13, and RLC residue K6 near E10 of the ELC. All of the interacting ELC residues are on helix-A. RLC residues 19-24 were then altered to build the connection with F25 using the crystallographic modeling program “O” (Jones et al., 1991). All decisions to this point were subjective. The resulting “best” model was then minimized with 100 cycles of steepest descent energy minimization using an r-dependent dielectric constant of 4.0 (ε=4.0 rij). This was followed by 1000 cycles of adaptive basis Newton–Raphson, using an implicit solvent generalized Born model (Lee et al., 2003). After minimization, the model was subjected to CHARMM molecular dynamics using parameter set 27 including the CMAP torsion term (MacKerell et al., 2004). This simulation used generalized Born implicit solvent without a solvent-accessible surface area based cost of cavity. LCD simulations ran for 100 picoseconds. Both S19 phos and S19 dephos LCD simulations were computed while only the S19 phos state of the RLC was simulated. The time scales are not physiologically meaningful. All analyses were made using the MMTSB tool set (Feig et al., 2004).

Protein preparation

Site directed mutagenesis was used to introduce changes into the RLC, ELC or HC of smHMM, a construct that ends at R1175. The HC was FLAG-tagged at the C-terminus to facilitate purification by affinity chromatography. To express smHMM with mutant light chains, cells were simultaneously transfected with two viruses, one encoding for the HC and the other encoding for both light chains. Three days after infection, Sf9 cells were lysed in 10 mM imidazole, pH 7.2, 0.15 M NaCl, 5 mM MgCl2, 3 mM NaN3, 2 mM EGTA, 2 mM MgATP, 2 mM DTT, and protease inhibitors. The smHMM was isolated on an anti-FLAG affinity column, eluted with FLAG peptide, and dialyzed against 10 mM imidazole, pH 7.0, 40 mM NaCl, 1 mM NaN3, 1 mM MgCl2, 1 mM DTT, 1 μg/ml leupeptin, and 50% glycerol. The RLC on smHMM was phosphorylated by addition of 4 mM MgATP, 7.5 μg/ml calmodulin, and 10 μg/ml myosin light chain kinase in the presence of calcium overnight on ice. Mutations involving the RLC were more difficult to phosphorylate, and thus the MgATP concentration was increased to 10 mM, and the myosin light chain kinase concentration to 50 μg/ml. RLC phosphorylation was confirmed using 40% glycerol gels with samples dissolved in 7.5 M urea (Trybus, 2000). The smHMM concentration was determined by Bradford reagent with bovine serum albumin as a standard.

In Vitro Motility Assay

Phosphorylated smHMM at 0.1 mg/ml was mixed with 0.04 mg/ml actin and 1 mM MgATP and centrifuged for 20 min at 350,000 × g to remove smHMM that was unable to dissociate from actin in the presence of ATP. The motility assay was performed at 30°C in 25 mM imidazole, pH 7.5, 60 mM KCl, 4 mM MgCl2, 1 mM EGTA, 0.7% methylcellulose, 1 mM MgATP, 10 mM DTT, 3 mg/ml glucose, 0.1 mg/ml glucose oxidase, and 0.018 mg/ml catalase essentially as described (Trybus, 2000). Data were collected on a Zeiss Axiovert 10 inverted microscope with a Rolera MGi Plus camera and the Nikon NIS Elements software package. Velocities were analyzed using a semi-automated, filament-tracking program described in (Kinose et al., 1996).

ATPase Assays

Actin-activated ATPase activity was measured at 37 °C in 8 mM KCl, 10 mM imidazole, pH 7.0, 1 mM DTT, 1 mM NaN3, 1 mM MgCl2, 1 mM EGTA, and 25-75 μg/ml smHMM depending on the construct. The reactions were initiated by the addition of 2 mM MgATP. The reactions were stopped with SDS at six time points per actin concentration, and inorganic phosphate was determined colorimetrically (Trybus, 2000).

RESULTS

Model for the phosphorylated light chain domain

In constructing this model, we reasoned that ser19 phosphorylation could affect torsional motions within the LCD only if the PD interacted with some structural feature near the focus of the motion. The structure of the PD itself is not known. The closest landmark is F25 (smooth muscle myosin numbering is used throughout), the position of which is known from the structures of its homologs in the skeletal and scallop RLC crystal structures (Houdusse and Cohen, 1996; Rayment et al., 1993). With the first 18 residues of the PD built in an α-helical conformation and the remaining six residues in an extended conformation, the PD can be placed at the focus of motion in the HC between the ELC and the RLC (Fig. 1C).

The PD of the smooth muscle RLC contains eight basic and no acidic residues (Fig. 2A). Phosphorylation of S19 provides a single focus of negative charge. Simply truncating the first 16 residues of the PD, which results in a molecule that cannot be phosphorylated, produces an inactive 6S conformation of smooth muscle myosin (Ikebe et al., 1994). This work implicated four basic residues (K11, K12, R13 and R16) in these processes. The charge reversal RLC double mutant K11E/K12E reduced phosphorylation-induced activation of smooth muscle myosin to ~15% of control, with less of an effect on the ability of myosin to form the 10S state (Ikebe et al., 1994). A separate study that measured the effects of the single point mutations K11A and K12A saw no effect on the ability of dephosphorylated myosin to form the 10S conformation (Sweeney et al., 1994). Thus, positive charges at 11KK12 are important for disrupting head-head folding in the phosphorylated state. Conversely, mutations of R13 or R16 to alanine had no effect on ATPase activation, but did impair myosin's ability to form the folded 10S state (Ikebe et al., 1994; Sweeney et al., 1994). To account for these observations, our activated state model needed to locate potential interaction partners for these charged residues.

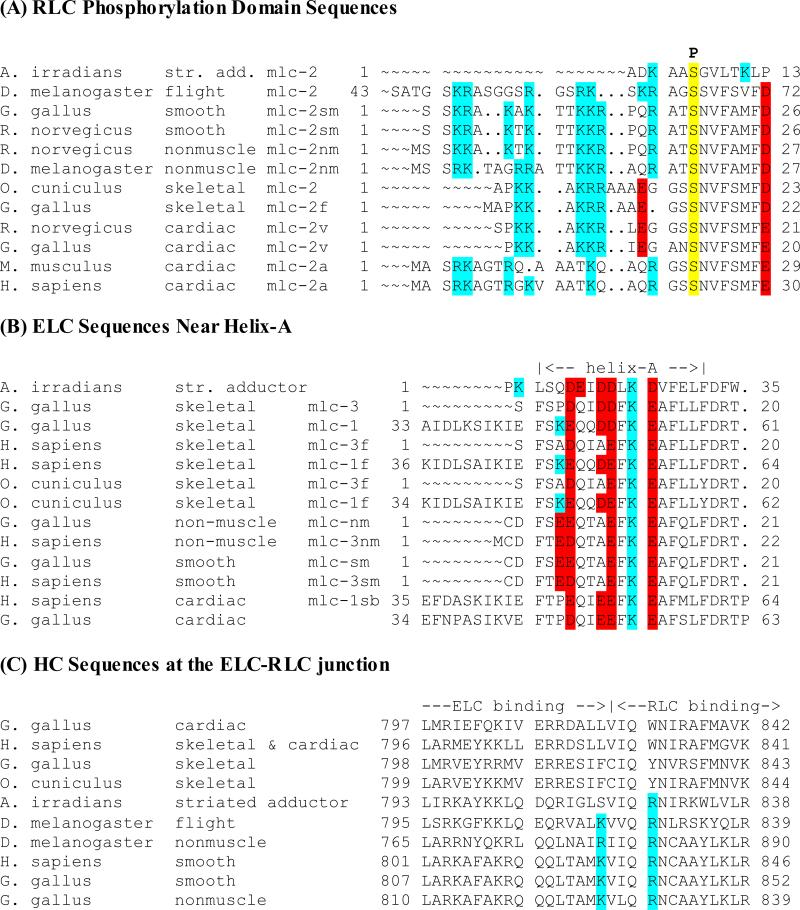

Figure 2. Sequences of the RLC, ELC and HC within the lever arm.

Basic residues are highlighted in cyan, acidic residues are highlighted in red, the position of the phosphorylated serine 19 is highlighted in yellow. The numbers to the left and right of each row of residues refer to the residue numbers of the first and last residues shown, not to the column positions. (A) RLC sequences. “P” denotes the position of the phosphorylatable serine in the smooth muscle RLC. Note that the serine, though invariant, is not always phosphorylated. (B) ELC sequences. Note that mlc-1 and cardiac sequences have an N-terminal extensions of ~33 residues. (C) Heavy chain sequences. Only those isoforms that are likely to fold into the 10S conformation with the asymmetric head-head interaction depicted in Figure 1 as well as the bent, hairpin structure of the rod domain have positive charges analogous to those of chicken smooth muscle myosin at residues 823 and 827.

Residue S19 of the smooth muscle RLC forms a convenient landmark for comparing sequences and it is nearly invariant across all aligned RLCs (Fig. 2A). Of the RLC sequences we examined, 13 were vertebrate smooth muscle or non-sarcomeric forms, and all but one had conserved KKR sequences beginning 8 residues upstream from the phosphorylatable serine (Fig. 2A). Among cardiac myosin RLCs, eight of nine ventricular isoforms followed the smooth muscle pattern; the single outlier having a KKK sequence. Cardiac atrial isoforms do not follow this pattern. Vertebrate skeletal muscle myosin RLCs generally have a KRR sequence but displaced 8 to 10 residues from the invariant serine.

The N-terminus of the ELC, which forms helix-A, is proximal to the exposed region of the myosin HC and the PD. Sequence alignment (Fig. 2B) showed that three acidic residues on or near helix-A are highly conserved. Along helix-A, E6, E10 and E13 face toward the gap between ELC and RLC (Fig. 3). Though highly conserved, they have no interacting partners in any of the reported crystal structures. In 78 of the ELC sequences aligned, all but 2 had acidic residues at these locations and of the two that did not, each had two of the three residues. E10 and E13 are identical among the smooth and non-muscle residues whereas E6 in many cases can be substituted by aspartic acid, D. Another acidic residue, E5, faces away from the PD and forms a salt bridge with K12 of the ELC in the smooth muscle myosin motor domain-ELC crystal structure (Dominguez et al., 1998).

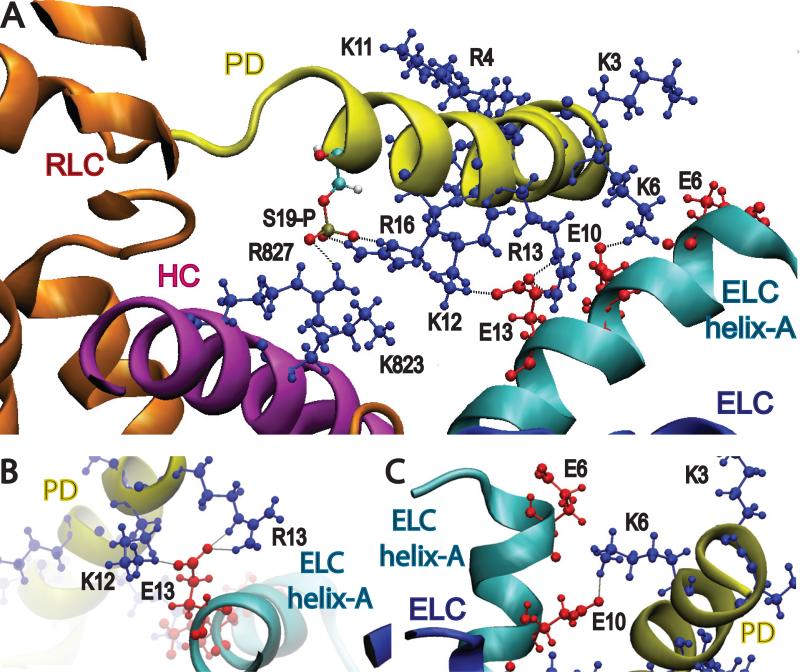

Figure 3. Principal interactions of the phosphorylated LCD atomic model.

(A) View of PD interactions with the HC and helix-A of the ELC in the neighborhood of RLC S19 when phosphorylated (S19-P). The phosphate of S19-P is shown in gray and its bound oxygens in red. Principal interactions with S19-P are with HC residue R827 and RLC residue R16. Basic residues are colored blue and acidic residues are colored red. (B) View in the neighborhood of ELC residue E13. Principal interactions are with RLC residues K12 and R13. (C) View in the neighborhood of ELC residue E10. The principal interaction is between E10 and K6.

The PD is highly positively charged. Among vertebrate smooth and non-muscle RLCs, there are no acidic residues before D26 (Fig. 2A). In addition, the region between the ELC and RLC is not rich in acidic residues except for helix-A of the ELC. The HC in this region is basic and most of the acidic residues of the RLC in the neighborhood (E111 & E112) are on the opposite side of the HC from the PD. There are a number of basic amino acids on the HC in the region where the PD was docked in our model; these include R809, K810, K814 and R815. K814 forms a salt bridge with E111 of the RLC in our homology model. R815 on the HC faces away from the docked PD. Residues R809 and K810 are positioned near the end of the PD. R809 faces toward the interface of the HC and ELC. K810 also faces away from the nearest RLC residues, K3 and R4, both of which are too distant to interact.

After a short period of molecular dynamics, the PD moved quickly from its initial position but remained bound during the rest of the simulation by three sets of salt bridges, one to the HC and the others to helix-A of the ELC (Fig. 3A). S19-P remained docked to HC residue R827 and RLC residue R16 (Fig. 3A). RLC residues K12/R13 remained bound to E13 of the ELC (Fig. 3B), and K6 remained bound to E10 of the ELC (Fig. 3C). At the end of the simulation, E6 of the ELC appeared to be too distant to form a salt bridge with the PD. The first 19 PD residues remained in a helical conformation. The simulation therefore suggested three locations to test by site directed mutagenesis: K6, K12 and R13 of the RLC, E10 and E13 of the ELC and K823/R827 of the HC.

Mutational studies to test potential interactions

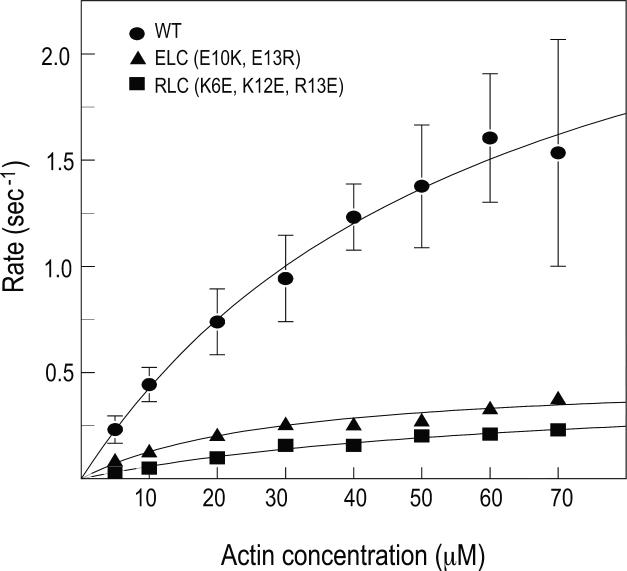

The activity of phosphorylated smHMM containing a mutant RLC was compared to that of the WT construct by actin-activated ATPase activity and in vitro motility. smHMM containing a triple charge reversal mutation of the RLC (K6E / K12E / R13E) was poorly activated when phosphorylated, with a Vmax that was ~15% that of the control phosphorylated WT smHMM (Fig. 4 and Table 1). Similar results were seen by in vitro motility (Table 1). The WT phosphorylated construct moved actin at a rate of 0.70 ±0.20 μm/sec (n=745), and 87% of the filaments in the field were motile. In contrast, few actin filaments were moved by the mutant RLC construct, and those that did moved very slowly (0.07±0.09, n=12). None of the unphosphorylated samples moved actin in the motility assays.

Figure 4. Actin-activated ATPase data for various phosphorylated HMM constructs.

WT, circles; HMM containing mutant RLC (K6E/K12E/R13E), squares; HMM containing mutant ELC (E10K/E13R), triangles. Vmax and Km values are as follows: WT, 3.0±0.3 sec−1, 61±12 μM; HMM with mutant RLC (K16E/K12E/R13E), 0.46±0.07 sec−1, 68±17 μM; HMM with mutant ELC (E10K, E13R), 0.49±0.06 sec−1, 28±8 μM.

Table 1.

Summary of ATPase activity and motility for HMM constructs

| RLC | ELC | Vmax (Sec-1) | Km (μM) | Motility (μm/sec) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| WT | WT | 3.0 ± 0.3 | 61 ± 12 | 0.70 ± 0.20 |

| K6E / K12E / R13E | WT | 0.46 ± 0.07 | 68 ± 17 | 0.07 ± 0.09 |

| WT | E10K / E13R | 0.49 ± 0.06 | 28 ± 8 | 0.26 ± 0.25 |

Similarly, phosphorylated myosin containing a mutant ELC (E10K/E13R) had a Vmax for the actin-activated ATPase activity that was ~ 15% of the control phosphorylated WT smHMM (Fig. 4 and Table 1). By motility, only ~20 % of the field moved, and those that did moved more slowly than WT (0.26±0.25, n=44). Both of these data sets are consistent with phosphorylation-dependent activation requiring an interaction between the PD and helix-A of the ELC.

In principle, myosin containing both RLC and ELC mutant light chains could evoke a “rescue” of activation, but in practice this did not occur. The actin-activated ATPase of myosin containing both mutant light chains was similar to that containing either mutant LC singly (Vmax =0.60±0.11 sec−1, Km=59±19 μM), suggesting that some essential interaction was not restored when charges were inverted.

Two mutations to the HC were also made, replacements of K823 and R827 with those residues found in either cardiac (K823L/ R827W) or skeletal (K823F/R827Y) muscle myosin. Neither of these phosphorylated constructs showed any difference in motility from that observed with the WT myosin HC (0.96±0.24 for WT versus 1.06±0.2 for K823F/R827Y; 0.62±0.18 for WT versus 0.84±0.04 for K823L/ R827W).

DISCUSSION

A surprising observation from the present work is that mutations in the ELC can have such a major effect on regulation. Previous studies that substituted the smooth muscle ELC with the skeletal muscle ELC showed no effect on regulation (Trybus, 1994), but the ELC from both species is highly conserved. ELC residues 97-101 which participate in the folded conformation of smHMM are conserved between these two species (Wendt et al., 2001). The present work shows that the involvement of helix-A of the ELC would also not be affected by a smooth to skeletal ELC substitution because the key residues, E10 and E13, are conserved. The importance of the ELC-RLC interaction in smooth muscle myosin regulation by phosphorylation is remarkably reminiscent of the crucial role of ELC-RLC interactions in the regulation of scallop myosin by Ca2+ (Houdusse and Cohen, 1996; Houdusse et al., 2000) although the interactions involving phosphorylation occur on the opposite side of HC as those involved in Ca2+ activation.

The model for the phosphorylated LCD helps to explain several observations from the literature, particularly by assigning interacting partners for the positively charged patch at 11KKR13. Two studies have investigated substitutions for lysine or arginine in the region K11 to R16 (Ikebe et al., 1994; Sweeney et al., 1994). Generally, substitutions for R13 and R16 have a larger effect on folding to the 10S conformation than on actin-activated ATPase activity, leading to the idea that regulation of the folded-to-extended conformation may be due to a simple reduction of net charge at the PD, while the mechanism governing phosphorylation-dependent activation is more complex (Sweeney et al., 1994). Charge ablation or reversal at K11 or K12 had less of an effect on folding than on actin-activated ATPase activity. In our model, K11 extends into solvent but K12 participates in a salt bridge with E13 of the ELC. Likewise, a salt bridge is formed between R16 and S19-P, as reported in earlier studies (Espinoza-Fonseca et al., 2007; Espinoza-Fonseca et al., 2008). The present model assumes a helical structure for the PD from S1 to S19, resulting in no obvious way that all three residues within 11KKR13 can interact simultaneously with ELC helix-A. An interaction would only be possible if the PD unfolded at this locus when phosphorylated.

Kast et al. (Kast et al., 2010) recently studied phosphorylation induced structural changes in the PD using both time-resolved fluorescence resonance energy transfer (TR-FRET) and molecular dynamics. These experiments indicated that the PD exists in two general structures, open and closed, which are characterized by differences in the distance between donor-acceptor probe pairs on the N-terminus of RLC (residues 2, 3, and 7) and residue 129 on the C-terminal domain. Phosphorylation increased the separation distance between the closed and open state by ~2 nm, increased the α-helix content of the PD and made it more dynamic. Our model compares favorably with theirs in the distance between the Cβ carbons of the probe pairs, and the helix in our model has a bend at K11/K12, which is approximately the location where the PD bends when converting between open and closed conformations. Their simulations were done on only RLC bound to HC, and therefore could not have predicted a role for helix-A of the ELC. Both models observed a salt bridge between S19-P and R16, an interaction that would be sterically favored if the PD was helical in this region, which is true for both models.

The model proposed here has several striking differences with models previously proposed for the PD. The Kast et al. model, which was investigated in both phosphorylated and unphosphorylated states, involves a completely α-helical structure for the PD, largely making it an extension of helix-A of the RLC (Kast et al., 2010). Another model (Jung et al., 2011) for the unphosphorylated state also incorporates a PD that is simply a helical extension of helix-A of the RLC. Our model does not require this type of structure. Indeed, it requires that the PD be unfolded and extended from F25 to S19, otherwise a connection cannot be made between 11KK12 and helix-A of the ELC.

Limitations of Molecular Dynamics

Our study, like those that preceded it (Espinoza-Fonseca et al., 2007; Espinoza-Fonseca et al., 2008; Kast et al., 2010; Ni et al., 2012), incorporated molecular dynamics (MD) simulations as a means of gaining further insight into the model. MD is ideal for refining a model structure and sampling multiple states of the structure. The chief disadvantage is that simulations can only rarely be done over time frames that are physiologically significant (ms duration) and so may not sample all possible structures. Simulations run for 100 ns or longer are common, but there is no guarantee that they have reached equilibrium. Our simulation ran for less than 1 ns and so cannot have reached equilibrium or even sampled many alternative structures. The chief benefit of MD in the present study was to show that the initial model structure was unstable but lead to a structure with better stability. Given the size of the LCD, which is the minimal relevant structure, we judged it unreasonable to run a long simulation to refine the structural model. Instead, the insights gained from our simulations allowed the model to be tested using site directed mutagenesis.

Most simulations have started with an α-helical structure for the PD. Using this starting model, the longest running simulations have been remarkably consistent, showing a dynamic structure that is more helical when S19 is phosphorylated and less helical when not. Most see no change in the imposed helix for P14, despite the fact that proline is regarded as a helix breaker. No effect was found when this site was mutated to alanine, a residue with favorable helix forming tendencies (Ikebe et al., 1994). Rather, more structural change was observed with substitutions for Q15 (Espinoza-Fonseca et al., 2007).

Heavy Chain Mutations

Few studies have investigated the role of the HC component of the lever arm. The sequence within the region G779-Q852 (using smooth muscle numbering) is 42% identical between chicken smooth and chicken skeletal muscle myosin, yet replacement of smooth muscle myosin HC residues 787-852 (containing both the RLC and ELC binding sites) with the corresponding sequence from chicken skeletal myosin had little effect on the in vitro movement of actin filaments by phosphorylated smHMM, but lost a significant degree of regulation as the dephosphorylated chimera moved actin at about half that rate (Trybus et al., 1998). Here, the focused point mutants (K823F/R827Y or K823L/R827W) had no significant effects on either phosphorylated or dephosphorylated smHMM. The two positive charges, K823/R827 on the HC may be involved in stabilizing the 10S conformation, because positive charges in this location are found only on those myosins, i.e. vertebrate smooth and non-muscle isoforms as well as scallop adductor, that are most likely to form the bent, hairpin fold of the myosin rod (Fig. 2C).

Mechanisms for ATPase activation

The interaction between the PD and helix-A of the ELC suggests at least three ways that phosphorylation could disrupt the head-head interaction leading to unfolding and ATPase activation: (1) alter the orientation of the “hook” in the myosin HC; (2) alter the bend in the heavy chain at the locus between light chains, and (3) alter the conformation of the ELC itself and its relationship with the HC.

The N-terminal domain of the RLC binds the so-called “hook” of the myosin HC

The orientation of the hook is one of the most striking differences between the structures of skeletal and scallop RLCs (Houdusse and Cohen, 1996). If a change in hook orientation were important in ATPase activation, there is some evidence to suggest that the hook orientation in dephosphorylated smooth muscle myosin would be similar to that of the skeletal RLC. Substitution of the skeletal RLC for the smooth muscle RLC maintains the inactive state and cannot be activated (Trybus and Chatman, 1993). The original atomic model fittings to 3-D images of the asymmetric head-head interaction found that a skeletal myosin RLC provided a better fit than a scallop myosin RLC (Wendt et al., 2001).

Upon phosphorylation, we would hypothesize that the hook orientation within the RLC changes toward that found in the scallop RLC. Consistent with this view, recent atomic model fitting into a 3-D map of phosphorylated smHMM obtained better results with a homology model based on the scallop RLC structure than with one based on the skeletal RLC structure (Baumann et al., 2012). Recent crystal structures showing that the hook orientation can vary even for molecules in the same unit cell would seem to support this hypothesis (Brown et al., 2011).

A change in the HC elbow is likely to disrupt the folded conformation

Very little difference was seen in the bend of the HC in the scallop LCD ±Ca2+ (Himmel et al., 2009), but this was in a structure lacking both the MD and S2. Baumann et al. compared the LCD structures for all of the atomic models fit to relaxed myosin structures showing the asymmetric head-head interaction with theirs obtained from phosphorylated smHMM (Baumann et al., 2012). They found that the HC bend for dephosphorylated (relaxed) blocked heads was greater than that for both dephosphorylated free heads and phosphorylated heads. That this bend is greater in the folded smHMM structure than in the available myosin S1 crystal structures with complete LCDs suggests that the folded conformation of dephosphorylated smHMM enforces an increase in the bend at this location. As this bend increases, the distance between F25 and ELC helix-A also increases requiring greater unfolding of the PD if the connection between 11KKR13 and helix-A of the ELC is to be made.

A recent mutational and molecular dynamics study (Ni et al., 2012) has drawn a similar conclusion regarding the importance of the RLC/ELC/HC interface on the activated state of phosphorylated smooth muscle myosin. Based on the scallop structure, the most significant interaction between the ELC and RLC occurs at ELC loop 1 containing residues R20 to K25 and an RLC loop containing residues M129 and G130. This same region is the site of Ca2+ binding in scallop myosin (Houdusse and Cohen, 1996). Mutations at this interface lead to normal inactivation in the dephosphorylated state. But in the phosphorylated state, mutations M129Q and G130C alone or in combination, abolish motility, with only a slight retention of ATPase activity. R20M and K25A had little or no effect on either motility or activity in the phosphorylated state. Molecular dynamics simulations suggested that the mutations increased the flexibility of the LCD at the locus between ELC and RLC, which in turn would favor the inactive, folded conformation. The placement of the PD was not considered, but a number of other mutations at sites similar to those reported here caused small losses in motility and activity (Ni et al., 2012).

In dephosphorylated smHMM, the ELC of the blocked head makes an intimate contact with the motor domain (Wendt et al., 2001)

The same contact occurs in the MD-ELC crystal structure (Dominguez et al., 1998) but not in other myosin II crystal structures that contain the RLC (Houdusse et al., 2000). The smooth muscle myosin MD-ELC conformation is unique among myosin X-ray crystal structures. By bridging the RLC and the ELC, the PD might alter the position of helix-A, in turn changing the ELC conformation enough to destabilize this contact. This contribution need not be entirely independent of a potential change to the HC bend within the LCD or changes in the hook orientation.

Summary

Our model for the position of the PD in the phosphorylated state proposes a linkage between the RLC N-terminal domain, which binds the HC “hook”, with the ELC that extends across the HC elbow. In so doing, it provides a mechanism for altering three sets of interactions that may be involved in smooth muscle myosin regulation. Much of the literature on smooth muscle myosin regulation can be summarized as indicating that a combination of interactions across multiple domains contribute to ATPase down regulation. These interactions extend from the motor domains all the way to the coiled-coil rod domain. What has not been clear is how the simple act of phosphorylation can disrupt so many interactions. The model described here contributes towards a more complete answer.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This work was supported by grants AR47421 (to KAT) and AR53975 (to SL) from NIAMSD /NIH and HL38113 (to KMT) from NHLBI/NIH and financial support from the Center for Multiscale Modeling Tools for Structural Biology (RR12255, to CLB III). Its contents are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of the NIAMS, NHLBI or NIH.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

REFERENCES

- Baumann BA, Taylor DW, Huang Z, Tama F, Fagnant PM, Trybus KM, Taylor KA. Phosphorylated smooth muscle heavy meromyosin shows an open conformation linked to activation. J Mol Biol. 2012;415:274–287. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2011.10.047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown JH, Kumar VS, O'Neall-Hennessey E, Reshetnikova L, Robinson H, Nguyen-McCarty M, Szent-Gyorgyi AG, Cohen C. Visualizing key hinges and a potential major source of compliance in the lever arm of myosin. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011;108:114–119. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1016288107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burgess SA, Yu S, Walker ML, Hawkins RJ, Chalovich JM, Knight PJ. Structures of smooth muscle myosin and heavy meromyosin in the folded, shutdown state. J Mol Biol. 2007;372:1165–1178. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2007.07.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Butler BA. Sequence analysis using GCG. Methods Biochem Anal. 1998;39:74–97. doi: 10.1002/9780470110607.ch4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Craig R, Smith R, Kendrick-Jones J. Light-chain phosphorylation controls the conformation of vertebrate non-muscle and smooth muscle myosin molecules. Nature. 1983;302:436–439. doi: 10.1038/302436a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cremo CR, Sellers JR, Facemyer KC. Two heads are required for phosphorylation-dependent regulation of smooth muscle myosin. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:2171–2175. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.5.2171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cross RA, Cross KE, Sobieszek A. ATP-linked monomer-polymer equilibrium of smooth muscle myosin: the free folded monomer traps ADP.Pi. EMBO J. 1986;5:2637–2641. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1986.tb04545.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dominguez R, Freyzon Y, Trybus KM, Cohen C. Crystal structure of a vertebrate smooth muscle myosin motor domain and its complex with the essential light chain: visualization of the pre- power stroke state. Cell. 1998;94:559–571. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81598-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Espinoza-Fonseca LM, Kast D, Thomas DD. Molecular dynamics simulations reveal a disorder-to-order transition on phosphorylation of smooth muscle myosin. Biophys J. 2007;93:2083–2090. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.106.095802. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Espinoza-Fonseca LM, Kast D, Thomas DD. Thermodynamic and structural basis of phosphorylation-induced disorder-to-order transition in the regulatory light chain of smooth muscle myosin. J Am Chem Soc. 2008;130:12208–12209. doi: 10.1021/ja803143g. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feig M, Karanicolas J, Brooks CL., 3rd MMTSB Tool Set: enhanced sampling and multiscale modeling methods for applications in structural biology. J Mol Graph Model. 2004;22:377–395. doi: 10.1016/j.jmgm.2003.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Himmel DM, Mui S, O'Neall-Hennessey E, Szent-Gyorgyi AG, Cohen C. The onoff switch in regulated myosins: different triggers but related mechanisms. J Mol Biol. 2009;394:496–505. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2009.09.035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Houdusse A, Cohen C. Structure of the regulatory domain of scallop myosin at 2 A resolution: implications for regulation. Structure. 1996;4:21–32. doi: 10.1016/s0969-2126(96)00006-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Houdusse A, Szent-Gyorgyi AG, Cohen C. Three conformational states of scallop myosin S1. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2000;97:11238–11243. doi: 10.1073/pnas.200376897. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Humphrey W, Dalke A, Schulten K. VMD: visual molecular dynamics. J Mol Graph Model. 1996;14:33–38. 27–28. doi: 10.1016/0263-7855(96)00018-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ikebe M, Ikebe R, Kamisoyama H, Reardon S, Schwonek JP, Sanders CR, 2nd, Matsuura M. Function of the NH2-terminal domain of the regulatory light chain on the regulation of smooth muscle myosin. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:28173–28180. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones TA, Zou JY, Cowan SW, Kjeldgaard Improved methods for building protein models in electron density maps and the location of errors in these models. Acta Crystallogr A. 1991;47(Pt 2):110–119. doi: 10.1107/s0108767390010224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jung HS, Komatsu S, Ikebe M, Craig R. Head-head and head-tail interaction: a general mechanism for switching off myosin II activity in cells. Mol Biol Cell. 2008a;19:3234–3242. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E08-02-0206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jung HS, Burgess SA, Billington N, Colegrave M, Patel H, Chalovich JM, Chantler PD, Knight PJ. Conservation of the regulated structure of folded myosin 2 in species separated by at least 600 million years of independent evolution. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008b;105:6022–6026. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0707846105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jung HS, Billington N, Thirumurugan K, Salzameda B, Cremo CR, Chalovich JM, Chantler PD, Knight PJ. Role of the tail in the regulated state of myosin 2. J Mol Biol. 2011;408:863–878. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2011.03.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kast D, Espinoza-Fonseca LM, Yi C, Thomas DD. Phosphorylation-induced structural changes in smooth muscle myosin regulatory light chain. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107:8207–8212. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1001941107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kinose F, Wang SX, Kidambi US, Moncman CL, Winkelmann DA. Glycine 699 is pivotal for the motor activity of skeletal muscle myosin. J Cell Biol. 1996;134:895–909. doi: 10.1083/jcb.134.4.895. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee MS, Feig M, Salsbury FR, Jr., Brooks CL., III A new analytical approximation to the standard molecular volume definition and its application to generalized Born calculations. J Comput Chem. 2003;24:1348–1356. doi: 10.1002/jcc.10272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu J, Wendt T, Taylor D, Taylor K. Refined model of the 10S conformation of smooth muscle myosin by cryo-electron microscopy 3D image reconstruction. J Mol Biol. 2003;329:963–972. doi: 10.1016/s0022-2836(03)00516-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacKerell AD, Jr., Feig M, Brooks CL., 3rd Improved treatment of the protein backbone in empirical force fields. J Am Chem Soc. 2004;126:698–699. doi: 10.1021/ja036959e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nag S, Suzuki H, Sosinski J, Seidel JC. Conformational changes in myosin and heavy meromyosin from chicken gizzard associated with phosphorylation. Prog Clin Biol Res. 1987;245:91–108. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nelson WD, Blakely SE, Nesmelov YE, Thomas DD. Site-directed spin labeling reveals a conformational switch in the phosphorylation domain of smooth muscle myosin. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:4000–4005. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0401664102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ni S, Hong F, Haldeman BD, Baker JE, Facemyer KC, Cremo CR. Modification of interface between regulatory and essential light chains hampers phosphorylation-dependent activation of smooth muscle myosin. J Biol Chem. 2012;287:22068–22079. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112.343491. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rayment I, Rypniewsky WR, Schmidt-Bäse K, Smith R, Tomchick DR, Benning MM, Winkelmann DA, Wesenberg G, Holden HM. Three-dimensional structure of myosin subfragment-1: a molecular motor. Science. 1993;261:50–58. doi: 10.1126/science.8316857. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rost B, Yachdav G, Liu J. The PredictProtein server. Nucleic Acids Res. 2004;32:W321–326. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkh377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sellers J. Mechanism of the phosphorylation-dependent regulation of smooth muscle heavy meromyosin. J Biol Chem. 1985;260:15815–15819. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sellers JR, Eisenberg E, Adelstein RS. The binding of smooth muscle heavy meromyosin to actin in the presence of ATP. Effect of phosphorylation. J Biol Chem. 1982;257:13880–13883. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suzuki H, Stafford WF, 3rd, Slayter HS, Seidel JC. A conformational transition in gizzard heavy meromyosin involving the head-tail junction, resulting in changes in sedimentation coefficient, ATPase activity, and orientation of heads. J Biol Chem. 1985;260:14810–14817. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sweeney HL, Chen LQ, Trybus KM. Regulation of asymmetric smooth muscle myosin II molecules. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:41273–41277. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M008310200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sweeney HL, Yang Z, Zhi G, Stull JT, Trybus KM. Charge replacement near the phosphorylatable serine of the myosin regulatory light chain mimics aspects of phosphorylation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1994;91:1490–1494. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.4.1490. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tama F, Feig M, Liu J, Brooks CL, 3rd, Taylor KA. The requirement for mechanical coupling between head and S2 domains in smooth muscle myosin ATPase regulation and its implications for dimeric motor function. J Mol Biol. 2005;345:837–854. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2004.10.084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trybus KM. Assembly of cytoplasmic and smooth muscle myosin. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 1991;3:105–111. doi: 10.1016/0955-0674(91)90172-u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trybus KM. Regulation of expressed truncated smooth muscle myosins. Role of the essential light chain and tail length. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:20819–20822. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trybus KM. Biochemical studies of myosin. Methods. 2000;22:327–335. doi: 10.1006/meth.2000.1085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trybus KM, Chatman TA. Chimeric regulatory light chains as probes of smooth muscle myosin function. J Biol Chem. 1993;268:4412–4419. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trybus KM, Huiatt TW, Lowey S. A bent monomeric conformation of myosin from smooth muscle. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1982;79:6151–6155. doi: 10.1073/pnas.79.20.6151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trybus KM, Naroditskaya V, Sweeney HL. The light chain-binding domain of the smooth muscle myosin heavy chain is not the only determinant of regulation. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:18423–18428. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.29.18423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trybus KM, Freyzon Y, Faust LZ, Sweeney HL. Spare the rod, spoil the regulation: necessity for a myosin rod. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1997;94:48–52. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.1.48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wendt T, Taylor D, Trybus KM, Taylor K. Three-dimensional image reconstruction of dephosphorylated smooth muscle heavy meromyosin reveals asymmetry in the interaction between myosin heads and placement of subfragment 2. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2001;98:4361–4366. doi: 10.1073/pnas.071051098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woodhead JL, Zhao FQ, Craig R, Egelman EH, Alamo L, Padron R. Atomic model of a myosin filament in the relaxed state. Nature. 2005;436:1195–1199. doi: 10.1038/nature03920. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao FQ, Craig R, Woodhead JL. Head-head interaction characterizes the relaxed state of Limulus muscle myosin filaments. J Mol Biol. 2009;385:423–431. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2008.10.038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zoghbi ME, Woodhead JL, Moss RL, Craig R. Three-dimensional structure of vertebrate cardiac muscle myosin filaments. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:2386–2390. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0708912105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]