Abstract

Pre-mRNA splicing, the removal of noncoding intron sequences from the pre-mRNA, is a critical reaction in eukaryotic gene expression. Pre-mRNA splicing is carried out by a remarkable macromolecular machine, the spliceosome, which undergoes dynamic rearrangements of its RNA and protein components to assemble its catalytic center. While significant progress has been made in describing the “moving parts” of this machine, the mechanisms by which spliceosomal proteins mediate the ordered rearrangements within the spliceosome remain elusive. Here we explore recent evidence from proteomics studies revealing extensive post-translational modification of splicing factors. While the functional significance of most of these modifications remains to be characterized, we describe recent studies in which the roles of specific post-translational modifications of splicing factors have been characterized. These examples illustrate the importance of post-translational modifications in spliceosome dynamics

Introduction

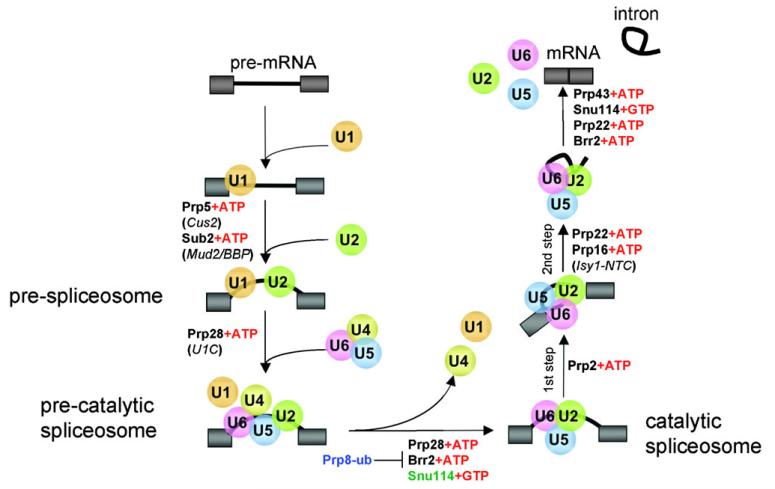

In eukaryotes, removal of introns from pre-mRNA is carried out by a large, dynamic macromolecular machine called the spliceosome. Splice site recognition, spliceosome assembly, and catalysis of the two transesterification steps are achieved by the coordinated activities of five spliceosomal snRNAs (U1, U2, U4, U5, and U6) and their associated proteins. Biochemical studies over the last 30 years have revealed much about the protein components of the spliceosomal snRNPs (small nuclear ribonucleoproteins) and their stepwise assembly to form the catalytically active spliceosome (reviewed in ref. 1-4 and illustrated in Fig. 1). Despite substantial advances in understanding the stepwise assembly of the spliceosome, the complex and highly dynamic nature of the splicing reaction still presents significant challenges to understanding the mechanistic details of splicing regulation.

Fig. 1.

Dynamic RNP rearrangements occur throughout the spliceosome assembly pathway. The snRNPs are depicted as colored balls. DExD/H proteins are shown at each step, and the proteins with which the DExD/H proteins interact (and which have opposing functions) are shown in italics. The GTPase Snu114, which is a ubiquitin conjugate and coordinates Brr2 activity, is indicated in green text. Prp8 is also included to illustrate how post-translational modifications fit into the pathway.

Here we explore recent evidence from proteomics studies revealing extensive post-translational modification of splicing factors. Although the functional significance of many modifications remains to be elucidated, we describe recent examples of post-translational modifications for which specific regulated steps have been identified. These studies provide exciting insights into the likely functions of post-translational modifications in regulating the elegant choreography of the spliceosome.

Post-translational modifications regulate dynamic processes

Post-translational modifications (PTMs) such as phosphorylation, ubiquitination, acetylation, and O-GlcNAcylation work to fine tune nearly every cellular process by causing changes in a protein’s activity, cellular localization, and interactions with other factors. PTMs may contribute to the splicing cycle and splicing fidelity by facilitating the physical rearrangements of the spliceosome, controlling the timing of these rearrangements, regulating splicing factor activities, or altering the mRNP composition assembled on a particular transcript.

A recent report nicely illustrates the ways in which a particular PTM—ubiquitination—regulates the timing of spliceosome dynamics in budding yeast (Saccharomyces cerevisiae). During spliceosome assembly, the U4/U6 U5 tri-snRNP associates with the pre-mRNA, whereupon the spliceosome is “activated,” in part by the release of the U4 snRNP (Fig. 2). A member of the DExD/H box family of proteins, Brr2, facilitates this process by unwinding the U4/U6 RNA duplex. Like Brr2, each of the eight DExD/H box proteins that have been shown to play a crucial role in splicing hydrolyzes ATP to drive energy-rich RNA–RNA and RNA–protein rearrangements (reviewed in ref. 5); hence, their activities are tightly regulated. Bellare et al. discovered that the ability of Brr2 to unwind U4/U6 is suppressed by ubiquitin, most likely when it is conjugated to the highly conserved U5 snRNP protein, Prp8.6,7 It is thought that when Prp8 ubiquitination is disrupted (or when the ubiquitin moiety is occluded), Brr2 activity is no longer suppressed, and this activity leads to tri-snRNP disassembly.7 Misregulation of Brr2 causes premature unwinding of U4/U6 and aborts the splicing pathway. Since Brr2 is also involved in a later step in splicing—U2/U6 unwinding—during spliceosome disassembly,8 it is possible that this later step is also regulated by Brr2 ubiquitination. This example highlights the importance of ubiquitination in regulating spliceosome dynamics via its effects on both the physical and the temporal interactions of splicing factors.

Fig. 2.

Ubiquitination regulates Brr2’s role in formation of a catalytically active spliceosome. During the splicing reaction, formation of the catalytic spliceosome is facilitated by rearrangements resulting in tri-snRNP disassembly and U4 snRNP release. Ubiquitin negatively regulates spliceosome activation by suppressing Brr2-mediated U4/U6 unwinding. Once the ubiquitin moiety is removed or occluded, Brr2 activity is no longer suppressed and facilitates U4 snRNP dissociation.

Large-scale proteome analysis enables a better understanding of PTMs in splicing

As this example illustrates, it is crucial to understand how PTMs contribute to splicing regulation, but the splicing reaction presents particular difficulties for identifying PTMs and their effects. The spliceosome is highly dynamic, as are most PTMs. Capturing a splicing factor in a particular modified state is difficult, given the transient nature of splicing intermediates and of the modifications themselves. Furthermore, identification of the enzyme responsible for a particular modification is difficult, as its association with the spliceosome is likely to be transient. Lastly, as will be discussed below in more detail, some PTMs may be specific to particular environmental conditions.

The advent of proteomics and systems biology presents an opportunity to address some of the complex issues presented by the splicing reaction and machinery. Large-scale -omics investigations involve unbiased global analyses of cellular responses. Subsequent systems-style integration of these data sets allows for better understanding of the underlying biology. In the field of pre-mRNA splicing, proteomics studies have been used to determine the protein composition of each spliceosomal complex, thus providing valuable information about the structural rearrangements that occur at each step of the splicing cycle.9-19 These studies have been further informed by large-scale approaches to understanding spliceosome transitional states using drugs that block PTMs and reveal the compositions of intermediate complexes.20 The other proteomic studies have used mass spectrometry (MS) analysis to identify PTM substrates, including splicing factors, many of which are catalogued in the online database UniProt.21 The results of these studies are presented in Supplementary Table 1†,106-156 and the evidence linking each one to splicing is described below.

Phosphorylation

Reversible protein phosphorylation is used as a regulatory mechanism in nearly all cellular processes. Dynamic phosphorylation events are achieved via the interplay of protein kinases and phosphatases that promote phosphate addition and removal, respectively. Phosphorylation of proteins within complexes is of particular importance since it alters physical interactions (by disrupting some ionic interactions and facilitating others), protein stability, and enzymatic activities.22

Phosphorylation regulates many of the dynamic interactions that occur throughout spliceosome assembly, splicing catalysis, and spliceosome disassembly. Early work pointed to a role for cycles of protein phosphorylation and dephosphorylation by demonstrating that splicing cannot proceed in vitro in the presence of phosphatases or phosphatase inhibitors.23 Indeed, there are splicing factors representing each step in the splicing pathway that are phosphorylated, suggesting that phosphorylation and dephosphorylation are important throughout the splicing cycle (Supplementary Table 1†). Although phosphorylation is sure to play a role in guiding spliceosome dynamics, only a handful of the 100+ non-SR splicing factors have been reported as phosphorylation substrates and even fewer have been described at the mechanistic level. Since there are a number of excellent reviews of SR protein phosphorylation,24-29 these will not be discussed here.

One clear example of how dynamic phosphorylation and dephosphorylation modulates the activity of a single factor is the U2 snRNP protein SAP155. Phosphorylation of mammalian SAP155 occurs prior to or concomitant with splicing catalysis.30 SAP155 is then dephosphorylated during the second step of splicing by the PP1 or PP2A phosphatase or both.31 Recruitment of PP1 to SAP155 is mediated at least in part by NIPP1 (nuclear inhibitor of protein phosphatase 1), which recognizes and binds to hyperphosphorylated SAP155 and stimulates its dephosphorylation.32

Analysis of proteomic data leads to predictions about how phosphorylation affects discrete steps in splicing, including commitment complex formation and pre-spliceosome formation. For example, during commitment complex formation, the yeast branchpoint binding protein (BBP) and its partner Mud2 (SF1 and U2AF65, respectively, in humans) bind the branchpoint region of the pre-mRNA and form a bridging interaction with the U1 snRNP bound to the 5′SS.33,34 Subsequent pre-spliceosome formation requires the exchange of the U2 snRNP for BBP/SF1 and Mud2/U2AF65 at the branchpoint.33 Large-scale analyses have revealed that each of these factors is phosphorylated, a result which raises the possibility that the role of these factors in formation of commitment complexes and pre-spliceosomes might be regulated by their modification.35,36 Indeed, genetic interactions between Mud2 and the PP1 phosphatase suggest that the cycle of phosphorylation and dephosphorylation of one or all of these proteins may play a role in this step.37,38

Regulated phosphorylation of splicing factors may also be a mechanism by which the activities of specific proteins are regulated in response to cellular conditions. For instance, in two large-scale studies examining cell-cycle specific phosphorylation events, Cus2, the yeast U2 snRNP factor important for facilitating proper U2 snRNA folding,39 was found to be phosphorylated, a finding that raises the possibility that Cus2 has roles in splicing that are cell-cycle dependent. Mutations in Cus2 that suppress the deleterious effect caused by misfolded U2 snRNA lie in close proximity to a putative CKII site within the protein’s acidic domain. This domain is also extensively phosphorylated in the mammalian homolog of Cus2, Tat-SF1, a fact which further suggests that phosphorylation within this domain is important for Cus2 activity.40-45 Moreover, since recent studies illustrate that, under different environmental conditions, the splicing of a certain subset of genes requires the activity of different splicing factors,46 it is likely that conditions rendered by progression through the cell-cycle also require specific splicing factor activities (modulated by PTMs) to mediate the appropriate responses.

These studies highlight two outstanding questions about the role of phosphorylation in splicing; namely, how does phosphorylation affect protein activities such as RNA binding and protein-protein interactions? And what mechanisms does the spliceosome employ to ensure that protein phosphorylation occurs at the right time? Clearly, new approaches will need to be employed to determine the global effects of phosphorylation on splicing.

Ubiquitination

Ubiquitination involves the covalent attachment of the small, conserved peptide ubiquitin (ub) to a target protein, almost exclusively at a lysine residue. Ubiquitin addition is catalyzed by an enzymatic cascade involving an E1 ub-activating enzyme, followed by the activities of an E2 ub-conjugating enzyme and an E3 ub ligase (reviewed in ref. 47). This process is reversible as a result of the activities of deubiquitinating enzymes (reviewed in ref. 38 and 48). Monoubiquitination has emerged as an important signaling mechanism separate from the well-characterized role of polyubiquitination in proteolysis (reviewed in ref. 49). Monoubiquitination of both histone and non-histone protein targets plays a role in regulating a number of important reactions, including transcription, DNA repair, signal transduction, and receptor internalization (reviewed in ref. 50). Ubiquitination, in general, has been shown to regulate protein–protein interactions and often serves as a signal for subsequent phosphorylation events.51

In addition to recent studies suggesting that ubiquitination of Prp8 regulates tri-snRNP disassembly,6,7 there are other indications that ubiquitin or ubiquitin-like proteins (such as Sumo and Hub1) play additional roles in splicing. These moieties, and the enzymes responsible for their addition/removal, co-purify with splicing factors.16,52 Interestingly, a number of splicing factors that exhibit genetic and physical interactions with one another contain motifs similar to those found in the ubiquitination machinery. The presence of these motifs suggests that the splicing factors themselves are directly involved in ubiquitination events. The formation of the pre-spliceosome and the biogenesis of snRNPs involved in this step appear to be regulated by ubiquitination and deubiquitination. For example, Prp19, an essential member of the Nineteen Complex (NTC) that, along with the tri-snRNP, associates with the pre-mRNA for formation of the precatalytic spliceosome contains an E3 ligase U-box domain and exhibits ubiquitin ligase activity in vitro.53 Mutations within this U-box domain disrupt the NTC complex and produce splicing defects.54-56 Additionally, Sad1, an essential factor required for U4/U6 biogenesis and tri-snRNP addition, contains a C-terminal hydrolase (UCH) domain, which is typically associated with ubiquitin cleavage.57,58 These findings suggest that splicing factors may directly contribute to cycles of ubiquitination and deubiquitination to facilitate progression of the splicing reaction and that the targets of their activities are likely to be other splicing factors. Consistent with this idea, several splicing factors have been identified as ubiquitin conjugates including Snu114, the U5 snRNP GTPase protein which coordinates Brr2 activity (Supplementary Table 1†).59,60 Snu114 exhibits genetic interactions with Prp19 and Sad1,58 a fact which presents the possibility that the Snu114 ubiquitination state is modulated by the activities of these proteins.

Phosphorylation marks are known to promote or inhibit subsequent ubiquitination events by altering E3 ligase binding sites.51 This mechanism of sequential modification may serve to calibrate ubiquitination events by directing E3 ligase binding, which normally occurs with little preference for the primary sequence. The highly ordered process of spliceosomal rearrangement is well-suited to such a tightly coordinated series of modifications and leads to the prediction that splicing factors are multiply modified. Indeed, the yeast factors Prp19, Prp43, Snu114, Sad1, Prp8, Cbp80, and Hsh155 have been shown to be both phosphorylated and ubiquitinated (Supplementary Table 1†), and there are likely to be other examples. It is unclear if the addition of these modifications is coordinated or if they serve as completely independent marks, but it is easy to imagine the implications that this type of coordinated modification may have. Prp8 regulation may be an instance of coordinated modification since Prp8 contains many of these modifications, acts throughout splicing, and participates in a large number of sequential and coordinated RNA–RNA and RNA–protein rearrangements.61 Further studies are needed to address this model directly.

Acetylation

Protein acetylation at lysine residues is a dynamic modification whose function in transcription and chromatin regulation has long been of interest. Lysine acetylation and deacetylation are catalyzed by a group of enzymes known as lysine acetyltransferases (KATs) and lysine deacetylases (KDACs). Acetylation of non-histone targets is known to affect protein stability, protein-DNA interactions, sub-cellular localization, and transcriptional activity (reviewed in ref. 62). Recent proteomics studies have identified acetyl marks on a plethora of proteins involved in diverse cellular processes, including factors involved in splicing.63-66

In addition to large-scale studies identifying the targets of acetylation, biochemical studies in mammalian cells have shown that splicing factors that are the targets of acetylation also associate with acetylation/deacetylation machinery. For example, the U2 snRNP factor SAP130 associates with the KAT complex STAGA67 and is the target of acetylation.64 Likewise, the RNA helicase p68, which facilitates spliceosome formation by destabilizing the U1/5′SS interaction, associates with KDAC168 and is acetylated.64 However, it remains to be determined whether these splicing factors are the actual targets of the enzymes with which they associate.

A more direct role for acetylation in regulating splicing was suggested by Kuhn et al., who demonstrated that both KAT and KDAC inhibitors can affect splicing in vitro.20 This study used three KAT and three KDAC small molecule inhibitors to block splicing at distinct steps. The composition of the stalled spliceosomes was then analyzed by mass spectrometry. These studies identified unique splicing complexes that accumulated only in the absence of proper acetylation or deacetylation. For instance, the KAT inhibitor anacardic acid blocked splicing at a complex lacking several U1 snRNP, SR, and NTC proteins, a result which suggests that inhibiting acetylation prevents the stable association of these proteins. Even though in the absence of KAT inhibition these studies could not confirm acetylation of the missing proteins using anti-acetyl antibodies or radioactively labeled acetyl coenzyme A, the majority of the proteins absent from these stalled complexes, including both SR and non-SR proteins, have been identified as acetylation substrates in a large-scale study of proteins acetylated in vivo including FBP11, S164, SPF31, hPRP5, SRp40, SRp55, SC35, SRm160, SRm300, Prp19, and Cdc5.64 Further characterization of specific acetylation events using mutational analysis of acetylation substrates will be important for elucidating direct roles for acetylation in splicing.

The well-characterized role for KATs and KDACs in regulating chromatin dynamics presents the exciting possibility that lysine acetylation in vivo functions to coordinate transcription and splicing. Indeed, Gunderson and Johnson have shown that the acetyltransferase activity of the yeast KAT Gcn5 regulates co-transcriptional association of the U2 snRNP with the nascent transcript.69 The spatial proximity of the KATs and the splicing factors during co-transcriptional splicing may allow for acetylation of histones or splicing factors or both to affect co-transcriptional spliceosome assembly and the activities of specific splicing factors.

Glycosylation

Protein glycosylation—the addition of saccharides to proteins—has been shown to regulate a variety of cellular processes including protein folding, cell signaling, cell adhesion, and protein stability (reviewed in ref. 70 and 71). The addition of O-linked N-acetylglucosamine (O-GlcNAc) to serine and threonine residues has been shown to occur on numerous cytosolic and nuclear proteins. Like other PTMs, this modification is dynamic, with the level of the O-GlcNAc modulated by the opposing activities of O-GlcNAc transferases and β-N-acetylglucosaminidases.70,72 This reversible modification affects protein–protein and protein–DNA interactions, protein stability and activity, and cell signaling cascades.73 Given the diverse functional regulatory roles of O-GlcNAc modification, it is possible that this modification also plays a role in splicing dynamics.

Large-scale analyses have identified several splicing factors as modified by O-GlcNAc. SF3b3 (SAP130) was identified in a large-scale screen for O-GlcNAc-modified proteins from HeLa cells.73 Several yeast splicing factors were identified in a large-scale study using lectins that specifically bind GlcNAc, including Slu7, Prp19, Npl3, and Isy1.74,75 It remains to be determined whether O-GlycNAcylation of these mammalian and yeast splicing factors is important for their activities in splicing. Interestingly, O-GlcNAc modifies residues that can also be phosphorylated, and O-GlcNAc transferase stably associates with the phosphatase PP1, associations that suggest that this modification may directly compete with phosphorylation.70,71 Indeed, several factors are both phosphorylated and O-GlycNAcylated (Supplementary Table 1†), a fact which opens the possibility that there may be a regulated exchange of phosphates for O-GlcNAc on these proteins. Determining the specific role of O-GlcNAc transferases in splicing will yield valuable insights into the roles of this modification in spliceosome dynamics.

General roles for post-translational modifications of splicing factors

In the next two sections we consider how PTMs may contribute to two important aspects of splicing. First we describe how modification of DExD/H box proteins may regulate the timing and fidelity of dynamic rearrangements that occur during splicing. Second, we describe how post-translational modifications of splicing factors may allow splicing to be responsive to changes in the environment.

DExD/H proteins that guide splicing dynamics and fidelity are post-translationally modified

As described above, there are a number of examples illustrating that PTM of splicing factors can regulate the dynamic interactions that occur throughout the splicing pathway. Of particular interest are the eight conserved DExD/H-box proteins that drive many spliceosomal rearrangements and enforce splicing fidelity (Fig. 1). This class of proteins is characterized by the presence of a DExD/H motif along with six or seven other conserved motifs that determine their NTP-binding, NTP-hydrolysis, RNA-binding, and unwinding activities (reviewed in ref. 76). This key group of spliceosomal proteins hydrolyzes ATP to catalyze a number of both RNA-RNA and RNA-protein rearrangements that take place throughout the splicing cycle.77,78 The functional consequence of these activities is to progress, pause, or abort the splicing pathway,79 making DExD/H box proteins major splicing “decision-makers.” Recent reports indicate that post-translational modification of splicing factors is at least one mode of regulating this class of proteins.

Mammalian PRP28, a likely homolog of the yeast U5 snRNP DExD/H protein required for exchanging U6 snRNA for U1 snRNA at the 5′SS,5 must be phosphorylated by SRPK2 for its stable association with the tri-snRNP and formation of the pre-catalytic complex.80 Although it is not known precisely which protein–protein or protein–RNA interactions are altered by PRP28 phosphorylation, PRP28 phosphorylation appears to promote physical interactions that allow for stable association of the tri-snRNP and pre-spliceosome. Furthermore, proteomics studies show that PRP28 is underrepresented in catalytic spliceosomes,11 suggesting that PRP28 dissociates from the spliceosome before catalysis, perhaps as the authors suggest, mediated by its dephosphorylation.

The revelation that PRP28 must be phosphorylated to stably associate with the tri-snRNP raises the question of whether PTM is a general mechanism for regulating the activity of DExD/H box proteins and their influence on splicing fidelity. A compelling model of splicing fidelity posits that each transition along the splicing pathway represents two kinetically competing conformations that must be stabilized or destabilized to advance or abort the splicing pathway.81 To this end, the dynamics of splicing often involve the pairing of opposing factors that interact to ensure proper timing and fidelity of the splicing reaction. The DExD/H box proteins play a crucial role in these rearrangements. For instance, Prp16 activity is crucial for the transition between the first and second steps of splicing.82,83 The activity of Prp16 is opposed by Isy1, a member of the Nineteen Complex (NTC), which acts to stabilize the first step conformation of the spliceosome.84 Perturbation of either Prp16 or Isy1 decreases splicing fidelity, a result which suggests that the interaction of these proteins regulates the kinetics of the first to second step transition. Similar antagonistic pairs involving DExD/H box proteins have been identified, including Sub2 and Mud2/BBP,33,85 Prp5 and Cus2,86,87 Brr2 and the U4/U6 helix,88-90 and Prp28 and U1C,91 where the interactions mediate substrate rearrangements that are necessary for splicing to progress (Fig. 1). It is likely that the other DExD/H proteins (Prp2, Prp22, and Prp43) employ similar mechanisms to ensure proper timing and fidelity of splicing.39,92

Despite the obvious importance of DExD/H proteins in the splicing reaction, the mechanisms that guide their specificity and activities are not well understood. We envision a model of spliceosome assembly whereby the DExD/H proteins associate with RNP subcomplexes and are poised to catalyze rearrangements when the correct conformations are achieved. PTMs on these DExD/H proteins may trigger their catalytic activities or PTMs on other auxiliary proteins may regulate their interactions with the DExD/H proteins. Indeed, post-translational modifications have been identified for all of the spliceosomal DExD/H box proteins and their partner proteins (Supplementary Table 1†).93-96

A possible mechanism for mediating the rapid splicing changes that occur in response to extracellular conditions

Competitive fitness and cell survival depend on a cell’s ability to swiftly respond to changes in the environment. Post-translational modification of spliceosomal proteins provides an efficient method for making splicing responsive to cellular conditions. Indeed, in metazoans, cell signaling affects alternative splicing by producing changes in SR protein phosphorylation in response to environmental cues.97,98 The question remains whether general splicing factors are also modified in response to environmental changes.

Two recent studies in budding yeast suggest global splicing patterns are uniquely sensitive to changes in specific splicing factors and changes in environmental conditions. Splicing-sensitive microarrays were used to demonstrate that mutation of core splicing factors produces different splicing profiles, a finding which suggests that splicing of each transcript is sensitive to the activities of specific proteins.99 Moreover, yeast cells exposed to changes in environmental conditions undergo rapid (within 2 minutes) changes in their genome-wide splicing profiles that are unique to the stimuli.46 Taken together, these studies produce an intriguing model that, in response to environmental changes, rapid PTMs alter the activities of specific splicing factors to modulate their roles in removing specific introns.

For example, not only is Prp8 ubiquitinated (as described above), but it also contains a JAB/MNP-like domain, which is implicated in binding ubiquitin. Upon amino acid starvation, two different alleles of Prp8 with mutations that flank the protein’s JAB/MNP-like domain produce different splicing profiles.99 Mutations of the JAB/MNP-like domain reduce both ubiquitin binding and U4/U6-U5 tri-snRNP levels, reductions that demonstrate that ubiquitin contributes to Prp8’s role in splicing.6,7 These data raise the possibility that modification within this portion of the protein contributes to substrate specificity and implicates ubiquitin binding by Prp8 as important in splicing responses to the environment. While this hypothesis remains to be tested, it will be interesting to determine whether the same stress conditions used in this study produce changes in the levels of ubiquitin-bound Prp8 and U4/U6-U5 tri-snRNP. Furthermore, it will be interesting to determine if ubiquitin-mediated intramolecular interactions in Prp8 contribute to its activity.

Future directions

Post-translational modifications have proven to be an important mechanism for regulating the highly dynamic interactions that guide the splicing cycle and ensure splicing fidelity. While proteomic studies have provided valuable information about PTM substrates, the next important steps toward understanding the role of PTMs in splicing must involve elucidating the functional consequences of these modifications. Outstanding questions to be addressed include determining which PTM events are required for each step of the splicing cycle, how combinations of modifications affect splicing factor activity, and under what conditions specific modifications are required. Although current detection technologies and certain biochemical aspects of PTMs present specific challenges in achieving these three goals, integrating the current data sets with new proteomics data that become available will be key to advancing our understanding of global splicing dynamics.

It is also important to note the likelihood that some PTMs identified in proteomics studies are not important for the target’s role in splicing. In addition to regulating a protein’s function, PTMs may mark a protein for proper folding, degradation, or trafficking. Additionally, in the case of proteins that play multiple roles in gene expression, PTMs may be important for other, non-splicing functions of the proteins. It is also possible that some PTMs are nonspecific. For example, recent studies of the evolution of protein phosphorylation sites indicate that some phosphorylation events occur nonspecifically on disordered protein surfaces.100 Because many kinases are promiscuous, nonspecific modifications may occur, particularly on proteins that are complexed with a true target protein (i.e., are in close proximity with the kinase). These sites probably arise from random mutations and are not conserved until they acquire a function. As discussed below, specific experimental design considerations will facilitate determining which PTMs are important for regulating the splicing cycle.

Challenge 1: revealing PTM dynamics during splicing

Although proteomic studies have greatly increased the number of identified spliceosomal proteins that are post-translationally modified by improving techniques for both enriching modified peptides and detecting them in mixed preparations, this number is still likely to be an underestimate. Furthermore, current MS methods are limited in the reproducibility of the data produced. However, new technologies like multiple reaction monitoring MS can be used to facilitate reliable, quantitative results with greater coverage.101-104 In addition to the technical challenges of various detection methods, the biology of PTMs presents challenges for identifying and characterizing PTMs during highly dynamic processes like splicing. Modifications are transient and modified peptides are likely to be in low abundance compared to their unmodified counterparts.

To study the timing of PTMs during the splicing cycle on a global scale, it will be necessary to combine proteomic analyses with methods that enrich for proteins specific to each step. For example, conditional alleles of individual splicing factors enrich for particular complexes under non-permissive temperatures. Because splicing is blocked, some PTMs may be stabilized and will provide information about the timing of particular splicing factor modifications. Furthermore, small molecules that inhibit specific modifications can be used to block spliceosomal rearrangements at specific intermediates, and mass spectrometry can complement these in vitro studies by identifying which proteins are modified at each step or within each complex. Improved methods for stabilizing PTMs, enrichment methods, and improvements in detection technologies will all likely contribute to an expanded set of PTMs and their role in splicing.

It is equally important to identify the enzymes responsible for catalyzing PTM addition and removal. However, these enzymes may associate only transiently with their substrates, thus decreasing the likelihood of their detection. Employing techniques such as in vivo crosslinking may enable the capture of such transient interactions in future studies.

Challenge 2: elucidating the PTM code

In addition to the dynamic changes in PTMs during the splicing cycle, it is apparent that some splicing factors are multiply modified, a fact which raises the question of whether these modifications are coordinated. It is known that such spatial and temporal crosstalk between PTMs is an important aspect of regulation. Roles for processive phosphorylation, crosstalk between multiple modifications within a single protein, and regulated stepwise-protein modification have already been established as important for protein function.

Recognition of particular splice sites is guided by an “mRNP code,” where the concerted activities of multiple splicing factors dictate splice site utilization.105 Similarly, splicing may be additionally regulated by a “PTM code”—where crosstalk between modifications within a single protein or multiple proteins modulates spliceosomal rearrangements and stepwise progression of the splicing cycle. Within a single protein there are typically several potential modification sites, some of which can be the target of more than one type of modification. Furthermore, crosstalk can exist between phosphorylation, ubiquitination, acetylation, and O-GlcNA-cylation. For instance, phosphorylation can promote ubiquitination by creating a recognition signal for E3 ligase binding;42,51 ubiquitination can, in turn, stimulate lysine acetylation, while acetylation can inhibit ubiquitination.51 Likewise, O-GlcNAcylation occurs at the same serine/threonine residues available for the phosphorylation and can, in fact, inhibit phosphorylation of surrounding residues.51 Regulation of the activity of a specific splicing factor may involve multiple modifications that guide its involvement in sequential steps in splicing. Similarly, proteins containing PTM-recognition domains that bind different types of modifications can act as dual recognition systems, binding only when its interacting partners are properly modified. Prp19, for example, is ubiquitinated, O-GlcNAcylated, and acetylated.35,55,64,66,74 It will be interesting to determine whether the addition of these modifications is coordinated and how each modification, whether independently or in combination, defines Prp19 activity.

Challenge 3: from ’omics to mechanism: determining the functional consequences of PTMs on splicing

The abundance of proteomics and genomics data has added breadth to our current knowledge of splicing factor modifications and how splicing changes under different conditions. However, the differences in the ways in which these data sets were prepared—different growth conditions, sample preparations, mutations, and detection methodologies—have made it difficult to integrate the data. Addressing the functional consequences of splicing factor PTMs requires a systems approach combining proteomics and genomics with analysis of individual factors.

As suggested by genome-wide splicing changes in S. cerevisiae in response to environmental changes, it is possible that certain PTMs occur only under a narrow set of conditions that trigger the activity of specific splicing factors or the splicing of specific transcripts.46 Likewise, particular transcripts may require a modified splicing factor to facilitate their splicing, while others may not. The splicing-specific microarray has proven to be a powerful tool for identifying splicing changes under specific conditions. Such arrays can be used in combination with PTM inhibitors, mutations in the PTM machinery, or mutations at splicing factor modification sites to identify how changes in PTM profiles produce concomitant changes in splicing. Additionally, the resulting data sets can be compared to identify conditions and mutations that produce overlapping effects on splicing and may reveal factors that act in concert under such conditions.

Conclusion

The spliceosome is an exquisitely coordinated macromolecular machine. The revelation that many splicing factors are post-translationally modified strongly suggests that many of the dynamic rearrangements that occur during the splicing cycle are regulated, in part, by the addition and removal of these PTMs. Understanding how the network of PTMs functions in regulating splicing will be the next exciting step toward understanding the coordinated mechanisms of spliceosome dynamics.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Dr Stephen Rader, Julia Claggett, Felizza Gunderson, and Dr Mary Fae McKay, for critical reading of the manuscript; Patricia Tu for her work on Table S1 (ESIw); Herve Tiriac for work on Fig. S1; and other members of the Johnson lab for useful comments and suggestions. This work was supported by an NSF CAREER award to T.L.J. (MCB-0448010) and an NSF predoctoral fellowship to S.L.M.

Biographies

Susannah L. McKay

Susy McKay is currently a PhD candidate in the lab of Prof. Tracy Johnson at the University of California at San Diego. She completed her BA at Rice University (2000) and taught math and science in the Peace Corps, Vanuatu (2000-2003). Susy’s current research interests are in understanding the molecular mechanisms that regulate pre-mRNA splicing, particularly phosphorylation.

Tracy L. Johnson

Tracy Johnson is an assistant professor at the University of California, at San Diego, where her laboratory studies mechanisms of pre-mRNA splicing and the coordination of RNA processing with transcription. In 2006 she received the Presidential Early Career Award for Scientists and Engineers. Dr Johnson was a Jane Coffin Childs Postdoctoral Fellow at the California Institute of Technology and received her PhD from the University of California, Berkeley.

Footnotes

Electronic supplementary information (ESI) available: Supplementary Table 1. Summary of post-translationally modified non-SR splicing factors across species. See DOI: 10.1039/c002828b

References

- 1.Valadkhan S. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 2007;17:310–315. doi: 10.1016/j.sbi.2007.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Matlin AJ, Moore MJ. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 2007;623:14–35. doi: 10.1007/978-0-387-77374-2_2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wahl MC, Will CL, Luhrmann R. Cell (Cambridge, Mass.) 2009;136:701–718. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.02.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Smith DJ, Query CC, Konarska MM. Mol. Cell. 2008;30:657–666. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2008.04.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Staley JP, Guthrie C. Mol. Cell. 1999;3:55–64. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)80174-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bellare P, Kutach AK, Rines AK, Guthrie C, Sontheimer EJ. RNA. 2006;12:292–302. doi: 10.1261/rna.2152306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bellare P, Small EC, Huang X, Wohlschlegel JA, Staley JP, Sontheimer EJ. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2008;15:444–451. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.1401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Small EC, Leggett SR, Winans AA, Staley JP. Mol. Cell. 2006;23:389–399. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2006.05.043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Behrens SE, Luhrmann R. Genes Dev. 1991;5:1439–1452. doi: 10.1101/gad.5.8.1439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Behzadnia N, Golas MM, Hartmuth K, Sander B, Kastner B, Deckert J, Dube P, Will CL, Urlaub H, Stark H, Luhrmann R. EMBO J. 2007;26:1737–1748. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601631. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bessonov S, Anokhina M, Will CL, Urlaub H, Luhrmann R. Nature. 2008;452:846–850. doi: 10.1038/nature06842. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chen YI, Moore RE, Ge HY, Young MK, Lee TD, Stevens SW. NucleicAcids Res. 2007;35:3928–3944. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkm347. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Herold N, Will CL, Wolf E, Kastner B, Urlaub H, Luhrmann R. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2009;29:281–301. doi: 10.1128/MCB.01415-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jurica MS, Licklider LJ, Gygi SR, Grigorieff N, Moore MJ. RNA. 2002;8:426–439. doi: 10.1017/s1355838202021088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kuhn-Holsken E, Lenz C, Sander B, Luhrmann R, Urlaub H. RNA. 2005;11:1915–1930. doi: 10.1261/rna.2176605. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rappsilber J, Ryder U, Lamond AI, Mann M. Genome Res. 2002;12:1231–1245. doi: 10.1101/gr.473902. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Stevens SW, Ryan DE, Ge HY, Moore RE, Young MK, Lee TD, Abelson J. Mol. Cell. 2002;9:31–44. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(02)00436-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Warkocki Z, Odenwalder P, Schmitzova J, Platzmann F, Stark H, Urlaub H, Ficner R, Fabrizio P, Luhrmann R. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2009;16:1237–1243. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.1729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zhou Z, Licklider LJ, Gygi SP, Reed R. Nature. 2002;419:182–185. doi: 10.1038/nature01031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kuhn AN, van Santen MA, Schwienhorst A, Urlaub H, Luhrmann R. RNA. 2009;15:153–175. doi: 10.1261/rna.1332609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jain E, Bairoch A, Duvaud S, Phan I, Redaschi N, E B, Suzek MJ, Martin P. McGarvey, Gasteiger E. Infrastructure for the life sciences: design and implementation of the UniProt website. BMC Bioinformatics. 2009;10:136. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-10-136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cohen P. TrendsBiochem. Sci. 2000;25:596–601. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mermoud JE, Cohen PT, Lamond AI. EMBO J. 1994;13:5679–5688. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1994.tb06906.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Blencowe BJ, Bowman JA, McCracken S, Rosonina E. Biochem. Cell Biol. 1999;77:277–291. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Valcarcel J, Green MR. Trends Biochem. Sci. 1996;21:296–301. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Fluhr R. Curr. Top.Microbiol. Immunol. 2008;326:119–138. doi: 10.1007/978-3-540-76776-3_7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hagiwara M. Biochim.Biophys. Acta, Proteins Proteomics. 2005;1754:324–331. doi: 10.1016/j.bbapap.2005.09.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Stojdl DF, Bell JC. Biochem. Cell Biol. 1999;77:293–298. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tenenbaum SA, Aguirre-Ghiso J. Mol. Cell. 2005;20:499–501. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2005.11.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wang C, Chua K, Seghezzi W, Lees E, Gozani O, Reed R. Genes Dev. 1998;12:1409–1414. doi: 10.1101/gad.12.10.1409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Shi Y, Reddy B, Manley JL. Mol. Cell. 2006;23:819–829. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2006.07.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Tanuma N, Kim SE, Beullens M, Tsubaki Y, Mitsuhashi S, Nomura M, K . Kawamura,, H Isono,, Koseki M, Sato M, Bollen K. Kikuchi, Shima H. J. Biol. Chem. 2008;283:35805–35814. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M805468200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kistler AL, Guthrie C. Genes Dev. 2001;15:42–49. doi: 10.1101/gad.851301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Fleckner J, Zhang M, Valcarcel J, Green MR. Genes Dev. 1997;11:1864–1872. doi: 10.1101/gad.11.14.1864. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Albuquerque CP, Smolka MB, Payne SH, Bafna V, Eng J, Zhou H. Mol. Cell. Proteomics. 2008;7:1389–1396. doi: 10.1074/mcp.M700468-MCP200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Smolka MB, Albuquerque CP, Chen SH, Zhou H. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2007;104:10364–10369. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0701622104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wilmes GM, Bergkessel M, Bandyopadhyay S, Shales M, Braberg H, Cagney G, Collins SR, Whitworth GB, Kress TL, Weissman JS, Ideker T, Guthrie C, Krogan NJ. Mol. Cell. 2008;32:735–746. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2008.11.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hershko A, Ciechanover A. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 1998;67:425–479. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.67.1.425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Perriman RJ, Ares M., Jr. Genes Dev. 2007;21:811–820. doi: 10.1101/gad.1524307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Yan D, Perriman R, Igel H, Howe KJ, Neville M, Ares M., Jr. Mol. Cell. Biol. 1998;18:5000–5009. doi: 10.1128/mcb.18.9.5000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wang B, Malik R, Nigg EA, Korner R. Anal. Chem. 2008;80:9526–9533. doi: 10.1021/ac801708p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Olsen JV, Blagoev B, Gnad F, Macek B, Kumar C, Mortensen P, Mann M. Cell(Cambridge, Mass.) 2006;127:635–648. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.09.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Dephoure N, Zhou C, Villen J, Beausoleil SA, Bakalarski CE, Elledge SJ, Gygi SP. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2008;105:10762–10767. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0805139105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Matsuoka S, Ballif BA, Smogorzewska A, McDonald ER, 3rd, Hurov KE, Luo J, Bakalarski CE, Zhao Z, Solimini N, Lerenthal Y, Shiloh Y, Gygi SP, Elledge SJ. Science. 2007;316:1160–1166. doi: 10.1126/science.1140321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Li X, Gerber SA, Rudner AD, Beausoleil SA, Haas W, Villen J, Elias JE, Gygi SP. J. Proteome Res. 2007;6:1190–1197. doi: 10.1021/pr060559j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Pleiss JA, Whitworth GB, Bergkessel M, Guthrie C. Mol. Cell. 2007;27:928–937. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2007.07.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Pickart CM, Eddins MJ. Biochim. Biophys. Acta, Mol. Cell Res. 2004;1695:55–72. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2004.09.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Amerik AY, Hochstrasser M. Biochim. Biophys. Acta, Mol. Cell Res. 2004;1695:189–207. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2004.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Sigismund S, Polo S, Di Fiore PP. Curr. Top. Microbiol. Immunol. 2004;286:149–185. doi: 10.1007/978-3-540-69494-6_6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Welchman RL, Gordon C, Mayer RJ. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2005;6:599–609. doi: 10.1038/nrm1700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Hunter T. Mol. Cell. 2007;28:730–738. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2007.11.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Makarov EM, Makarova OV, Urlaub H, Gentzel M, Will CL, Wilm M, Luhrmann R. Science. 2002;298:2205–2208. doi: 10.1126/science.1077783. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Hatakeyama S, Yada M, Matsumoto M, Ishida N, Nakayama KI. J. Biol.Chem. 2001;276:33111–33120. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M102755200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Ohi MD, Gould KL. RNA. 2002;8:798–815. doi: 10.1017/s1355838202025050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Ohi MD, Vander Kooi CW, Rosenberg JA, Chazin WJ, Gould KL. Nat. Struct. Biol. 2003;10:250–255. doi: 10.1038/nsb906. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Ohi MD, Vander Kooi CW, Rosenberg JA, Ren L, Hirsch JP, Chazin WJ, Walz T, Gould KL. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2005;25:451–460. doi: 10.1128/MCB.25.1.451-460.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Hunter S, Apweiler R, Attwood TK, Bairoch A, Bateman A, Binns D, Bork P, Das U, Daugherty L, Duquenne L, Finn RD, Gough J, Haft D, Hulo N, Kahn D, Kelly E, Laugraud A, Letunic I, Lonsdale D, Lopez R, Madera M, Maslen J, McAnulla C, McDowall J, Mistry J, Mitchell A, Mulder N, Natale D, Orengo C, Quinn AF, Selengut JD, Sigrist CJ, Thimma M, Thomas PD, Valentin F, Wilson D, Wu CH, Yeats C. Nucleic Acids Res. 2009;37:D211–D215. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkn785. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Brenner TJ, Guthrie C. Genetics. 2005;170:1063–1080. doi: 10.1534/genetics.105.042044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Tagwerker C, Flick K, Cui M, Guerrero C, Dou Y, Auer B, Baldi P, Huang L, Kaiser P. Mol. Cell. Proteomics. 2006;5:737–748. doi: 10.1074/mcp.M500368-MCP200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Peng J, Schwartz D, Elias JE, Thoreen CC, Cheng D, Marsischky G, Roelofs J, Finley D, Gygi SP. Nat. Biotechnol. 2003;21:921–926. doi: 10.1038/nbt849. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Grainger RJ, Beggs JD. RNA. 2005;11:533–557. doi: 10.1261/rna.2220705. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Kouzarides T. EMBO J. 2000;19:1176–1179. doi: 10.1093/emboj/19.6.1176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Basu A, Rose KL, Zhang J, Beavis RC, Ueberheide B, Garcia BA, Chait B, Zhao Y, Hunt DF, Segal E, Allis CD, Hake SB. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2009;106:13785–13790. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0906801106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Choudhary C, Kumar C, Gnad F, Nielsen ML, Rehman M, Walther TC, Olsen JV, Mann M. Science. 2009;325:834–840. doi: 10.1126/science.1175371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Kim SC, Sprung R, Chen Y, Xu Y, Ball H, Pei J, Cheng T, Kho Y, Xiao H, Xiao L, Grishin NV, White M, Yang XJ, Zhao Y. Mol. Cell. 2006;23:607–618. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2006.06.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Lin YY, Lu JY, Zhang J, Walter W, Dang W, Wan J, Tao SC, Qian J, Zhao Y, Boeke JD, Berger SL, Zhu H. Cell (Cambridge, Mass.) 2009;136:1073–1084. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.01.033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Martinez E, Palhan VB, Tjernberg A, Lymar ES, Gamper AM, Kundu TK, Chait BT, Roeder RG. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2001;21:6782–6795. doi: 10.1128/MCB.21.20.6782-6795.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Liu ZR. Mol. Cell.Biol. 2002;22:5443–5450. doi: 10.1128/MCB.22.15.5443-5450.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Gunderson FQ, Johnson TL. PLoS Genet. 2009;5:e1000682. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1000682. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Hart GW, Housley MP, Slawson C. Nature. 2007;446:1017–1022. doi: 10.1038/nature05815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Wells L, Hart GW. FEBS Lett. 2003;546:154–158. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(03)00641-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Hurtado-Guerrero R, Dorfmueller HC, van Aalten DM. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 2008;18:551–557. doi: 10.1016/j.sbi.2008.09.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Nandi A, Sprung R, Barma DK, Zhao Y, Kim SC, Falck JR, Zhao Y. Anal.Chem. 2006;78:452–458. doi: 10.1021/ac051207j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Gelperin DM, White MA, Wilkinson ML, Kon Y, Kung LA, Wise KJ, Lopez-Hoyo N, Jiang L, Piccirillo S, Yu H, Gerstein M, Dumont ME, Phizicky EM, Snyder M, Grayhack EJ. Genes Dev. 2005;19:2816–2826. doi: 10.1101/gad.1362105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Kung LA, Tao SC, Qian J, Smith MG, Snyder M, Zhu H. Mol. Syst.Biol. 2009;5:308. doi: 10.1038/msb.2009.64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Linder P, Tanner NK, Banroques J. Trends Biochem. Sci. 2001;26:339–341. doi: 10.1016/s0968-0004(01)01870-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Staley JP, Guthrie C. Cell (Cambridge, Mass.) 1998;92:315–326. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80925-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Hamm J, Lamond AI. Curr. Biol. 1998;8:R532–R534. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(07)00340-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Konarska MM, Query CC. Genes Dev. 2005;19:2255–2260. doi: 10.1101/gad.1363105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Mathew R, Hartmuth K, Mohlmann S, Urlaub H, Ficner R, Luhrmann R. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2008;15:435–443. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.1415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Query CC, Konarska MM. Mol. Cell. 2004;14:343–354. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(04)00217-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Schwer B, Guthrie C. EMBO J. 1992;11:5033–5039. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1992.tb05610.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Schwer B, Guthrie C. Nature. 1991;349:494–499. doi: 10.1038/349494a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Villa T, Guthrie C. Genes Dev. 2005;19:1894–1904. doi: 10.1101/gad.1336305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Wang Q, Zhang L, Lynn B, Rymond BC. Nucleic Acids Res. 2008;36:2787–2798. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkn144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Perriman R, Barta I, Voeltz GK, Abelson J, Ares M., Jr. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2003;100:13857–13862. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2036312100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Perriman R, Ares M., Jr. Genes Dev. 2000;14:97–107. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Kim DH, Rossi JJ. RNA. 1999;5:959–971. doi: 10.1017/s135583829999012x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Raghunathan PL, Guthrie C. Curr. Biol. 1998;8:847–855. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(07)00345-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.van Nues RW, Beggs JD. Genetics. 2001;157:1451–1467. doi: 10.1093/genetics/157.4.1451. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Chen JY, Stands L, Staley JP, Jackups RR, Jr., Latus LJ, Chang TH. Mol. Cell. 2001;7:227–232. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(01)00170-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Rutz B, Seraphin B. RNA. 1999;5:819–831. doi: 10.1017/s1355838299982286. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Roy J, Kim K, Maddock JR, Anthony JG, Woolford JL., Jr. RNA. 1995;1:375–390. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Tanaka N, Aronova A, Schwer B. Genes Dev. 2007;21:2312–2325. doi: 10.1101/gad.1580507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Tsai RT, Fu RH, Yeh FL, Tseng CK, Lin YC, Huang YH, Cheng SC. Genes Dev. 2005;19:2991–3003. doi: 10.1101/gad.1377405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Tsai RT, Tseng CK, Lee PJ, Chen HC, Fu RH, Chang KJ, Yeh FL, Cheng SC. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2007;27:8027–8037. doi: 10.1128/MCB.01213-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Shin C, Feng Y, Manley JL. Nature. 2004;427:553–558. doi: 10.1038/nature02288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Shin C, Manley JL. Nat.Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2004;5:727–738. doi: 10.1038/nrm1467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Pleiss JA, Whitworth GB, Bergkessel M, Guthrie C. PLoS Biol. 2007;5:e90. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0050090. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Holt LJ, Tuch BB, Villen J, Johnson AD, Gygi SP, Morgan DO. Science. 2009;325:1682–1686. doi: 10.1126/science.1172867. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Cox DM, Zhong F, Du M, Duchoslav E, Sakuma T, McDermott JC. J. Biomol. Tech. 2005;16:83–90. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Gocke CB, Yu H, Kang J. J. Biol. Chem. 2005;280:5004–5012. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M411718200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Mollah S, Wertz IE, Phung Q, Arnott D, Dixit VM, Lill JR. Rapid Commun. Mass Spectrom. 2007;21:3357–3364. doi: 10.1002/rcm.3227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Unwin RD, Griffiths JR, Whetton AD. Nat. Protoc. 2009;4:870–877. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2009.57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Stamm S. J. Biol.Chem. 2008;283:1223–1227. doi: 10.1074/jbc.R700034200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Beausoleil SA, Jedrychowski M, Schwartz D, Elias JE, Villen J, Li J, Cohn MA, Cantley LC, Gygi SP. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2004;101:12130–12135. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0404720101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Beausoleil SA, Villen J, Gerber SA, Rush J, Gygi SP. Nat. Biotechnol. 2006;24:1285–1292. doi: 10.1038/nbt1240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Giorgianni F, Zhao Y, Desiderio DM, Beranova-Giorgianni S. Electrophoresis. 2007;28:2027–2034. doi: 10.1002/elps.200600782. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Molina H, Horn DM, Tang N, Mathivanan S, Pandey A. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2007;104:2199–2204. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0611217104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Shu H, Chen S, Bi Q, Mumby M, Brekken DL. Mol. Cell. Proteomics. 2004;3:279–286. doi: 10.1074/mcp.D300003-MCP200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Smith JC, Duchesne MA, Tozzi P, Ethier M, Figeys D. J. Proteome Res. 2007;6:3174–3186. doi: 10.1021/pr070122r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Sweet SM, Bailey CM, Cunningham DL, Heath JK, Cooper HJ. Mol.Cell. Proteomics. 2009;8:904–912. doi: 10.1074/mcp.M800451-MCP200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Trost M, English L, Lemieux S, Courcelles M, Desjardins M, Thibault P. Immunity. 2009;30:143–154. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2008.11.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Villen J, Beausoleil SA, Gerber SA, Gygi SP. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2007;104:1488–1493. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0609836104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Zanivan S, Gnad F, Wickstrom SA, Geiger T, Macek B, Cox J, Fassler R, Mann M. J. Proteome Res. 2008;7:5314–5326. doi: 10.1021/pr800599n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Peng J, Cheng D. Methods Enzymol. 2005;399:367–381. doi: 10.1016/S0076-6879(05)99025-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Wilson KF, Wu WJ, Cerione RA. J. Biol. Chem. 2000;275:37307–37310. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C000482200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Cantin GT, Yi W, Lu B, Park SK, Xu T, Lee JD, Yates JR., 3rd J. Proteome Res. 2008;7:1346–1351. doi: 10.1021/pr0705441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Gevaert K, Staes A, Van Damme J, De Groot S, Hugelier K, Demol H, Martens L, Goethals M, Vandekerckhove J. Proteomics. 2005;5:3589–3599. doi: 10.1002/pmic.200401217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Imami K, Sugiyama N, Kyono Y, Tomita M, Ishihama Y. Anal. Sci. 2008;24:161–166. doi: 10.2116/analsci.24.161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Yu LR, Zhu Z, Chan KC, Issaq HJ, Dimitrov DS, Veenstra TD. J.Proteome Res. 2007;6:4150–4162. doi: 10.1021/pr070152u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Chi A, Huttenhower C, Geer LY, Coon JJ, Syka JE, Bai DL, Shabanowitz J, Burke DJ, Troyanskaya OG, Hunt DF. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S. A. 2007;104:2193–2198. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0607084104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Brill LM, Salomon AR, Ficarro SB, Mukherji M, Stettler-Gill M, Peters EC. Anal. Chem. 2004;76:2763–2772. doi: 10.1021/ac035352d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Daub H, Olsen JV, Bairlein M, Gnad F, Oppermann FS, Korner R, Greff Z, Keri G, Stemmann O, Mann M. Mol. Cell. 2008;31:438–448. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2008.07.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Gauci S, Helbig AO, Slijper M, Krijgsveld J, Heck AJ, Mohammed S. Anal. Chem. 2009;81:4493–4501. doi: 10.1021/ac9004309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Mayya V, Lundgren DH, Hwang SI, Rezaul K, Wu L, Eng JK, Rodionov V, Han DK. Sci. Signaling. 2009;2:ra46. doi: 10.1126/scisignal.2000007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Rikova K, Guo A, Zeng Q, Possemato A, Yu J, Haack H, Nardone J, Lee K, Reeves C, Li Y, Hu Y, Tan Z, Stokes M, Sullivan L, Mitchell J, Wetzel R, Macneill J, Ren JM, Yuan J, Bakalarski CE, Villen J, Kornhauser JM, Smith B, Li D, Zhou X, Gygi SP, Gu TL, Polakiewicz RD, Rush J, Comb MJ. Cell (Cambridge, Mass.) 2007;131:1190–1203. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.11.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128.Wilson-Grady JT, Villen J, Gygi SP. J. Proteome Res. 2008;7:1088–1097. doi: 10.1021/pr7006335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129.Guerrero C, Tagwerker C, Kaiser P, Huang L. Mol. Cell. Proteomics. 2006;5:366–378. doi: 10.1074/mcp.M500303-MCP200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130.Soufi B, Kelstrup CD, Stoehr G, Frohlich F, Walther TC, Olsen JV. Mol. BioSyst. 2009;5:1337–1346. doi: 10.1039/b902256b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131.Rush J, Moritz A, Lee KA, Guo A, Goss VL, Spek EJ, Zhang H, Zha XM, Polakiewicz RD, Comb MJ. Nat. Biotechnol. 2005;23:94–101. doi: 10.1038/nbt1046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 132.Vertegaal AC, Ogg SC, Jaffray E, Rodriguez MS, Hay RT, Andersen JS, Mann M, Lamond AI. J. Biol. Chem. 2004;279:33791–33798. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M404201200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 133.Gruhler A, Olsen JV, Mohammed S, Mortensen P, Faergeman NJ, Mann M, Jensen ON. Mol. Cell. Proteomics. 2005;4:310–327. doi: 10.1074/mcp.M400219-MCP200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 134.Carrascal M, Ovelleiro D, Casas V, Gay M, Abian J. J. Proteome Res. 2008;7:5167–5176. doi: 10.1021/pr800500r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 135.Han G, Ye M, Zhou H, Jiang X, Feng S, Jiang X, Tian R, Wan D, Zou H, Gu J. Proteomics. 2008;8:1346–1361. doi: 10.1002/pmic.200700884. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 136.Licht K, Medenbach J, Luhrmann R, Kambach C, Bindereif A. RNA. 2008;14:1532–1538. doi: 10.1261/rna.1129608. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 137.Dai J, Jin WH, Sheng QH, Shieh CH, Wu JR, Zeng R. J. Proteome Res. 2007;6:250–262. doi: 10.1021/pr0604155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 138.Chen R, Jiang X, Sun D, Han G, Wang F, Ye M, Wang L, Zou H. J. Proteome Res. 2009;8:651–661. doi: 10.1021/pr8008012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 139.Boudrez A, Beullens M, Waelkens E, Stalmans W, Bollen M. J. Biol. Chem. 2002;277:31834–31841. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M204427200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 140.Kim JE, Tannenbaum SR, White FM. J. Proteome Res. 2005;4:1339–1346. doi: 10.1021/pr050048h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 141.Ballif BA, Villen J, Beausoleil SA, Schwartz D, Gygi SP. Mol.Cell. Proteomics. 2004;3:1093–1101. doi: 10.1074/mcp.M400085-MCP200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 142.Nousiainen M, Sillje HH, Sauer G, Nigg EA, Korner R. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2006;103:5391–5396. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0507066103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 143.Ptacek J, Devgan G, Michaud G, Zhu H, Zhu X, Fasolo J, Guo H, Jona G, Breitkreutz A, Sopko R, McCartney RR, Schmidt MC, Rachidi N, Lee SJ, Mah AS, Meng L, Stark MJ, Stern DF, De Virgilio C, Tyers M, Andrews B, Gerstein M, Schweitzer B, Predki PF, Snyder M. Nature. 2005;438:679–684. doi: 10.1038/nature04187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 144.Lizcano JM, Goransson O, Toth R, Deak M, Morrice NA, Boudeau J, Hawley SA, Udd L, Makela TP, Hardie DG, Alessi DR. EMBO J. 2004;23:833–843. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 145.Tang LY, Deng N, Wang LS, Dai J, Wang ZL, Jiang XS, Li SJ, Li L, Sheng QH, Wu DQ, Li L, Zeng R. Mol. Cell. Proteomics. 2007;6:1952–1967. doi: 10.1074/mcp.M700120-MCP200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 146.Wang Y, Du D, Fang L, Yang G, Zhang C, Zeng R, Ullrich A, Lottspeich F, Chen Z. EMBO J. 2006;25:5058–5070. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601384. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 147.Tao WA, Wollscheid B, O’Brien R, Eng JK, Li XJ, Bodenmiller B, Watts JD, Hood L, Aebersold R. Nat. Methods. 2005;2:591–598. doi: 10.1038/nmeth776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 148.Ficarro SB, McCleland ML, Stukenberg PT, Burke DJ, Ross MM, Shabanowitz J, Hunt DF, White FM. Nat. Biotechnol. 2002;20:301–305. doi: 10.1038/nbt0302-301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 149.Zhou W, Ryan JJ, Zhou H. J. Biol. Chem. 2004;279:32262–32268. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M404173200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 150.Munton RP, Tweedie-Cullen R, Livingstone-Zatchej M, Weinandy F, Waidelich M, Longo D, Gehrig P, Potthast F, Rutishauser D, Gerrits B, Panse C, Schlapbach R, Mansuy IM. Mol. Cell.Proteomics. 2007;6:283–293. doi: 10.1074/mcp.M600046-MCP200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 151.Dagher SF, Fu XD. RNA. 2001;7:1284–1297. doi: 10.1017/s1355838201016077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 152.Heibeck TH, Ding SJ, Opresko LK, Zhao R, Schepmoes AA, Yang F, Tolmachev AV, Monroe ME, Camp DG, 2nd, Smith RD, Wiley HS, Qian WJ. J.Proteome Res. 2009;8:3852–3861. doi: 10.1021/pr900044c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 153.Trinidad JC, Specht CG, Thalhammer A, Schoepfer R, Burlingame AL. Mol. Cell.Proteomics. 2006;5:914–922. doi: 10.1074/mcp.T500041-MCP200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 154.Zhou H, Ye M, Dong J, Han G, Jiang X, Wu R, Zou H. J. Proteome Res. 2008;7:3957–3967. doi: 10.1021/pr800223m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 155.Beranova-Giorgianni S, Zhao Y, Desiderio DM, Giorgianni F. Pituitary. 2006;9:109–120. doi: 10.1007/s11102-006-8916-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 156.Seyfried NT, Xu P, Duong DM, Cheng D, Hanfelt J, Peng J. Anal. Chem. 2008;80(11):4161–4169. doi: 10.1021/ac702516a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.